Leisure Time Activities and Subjective Happiness in Early Adolescents from Three Ibero-American Countries: The Cases of Brazil, Chile and Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure Collection Procedure and Sample

2.2. Instrument

2.3. Data Analysis Design

3. Results

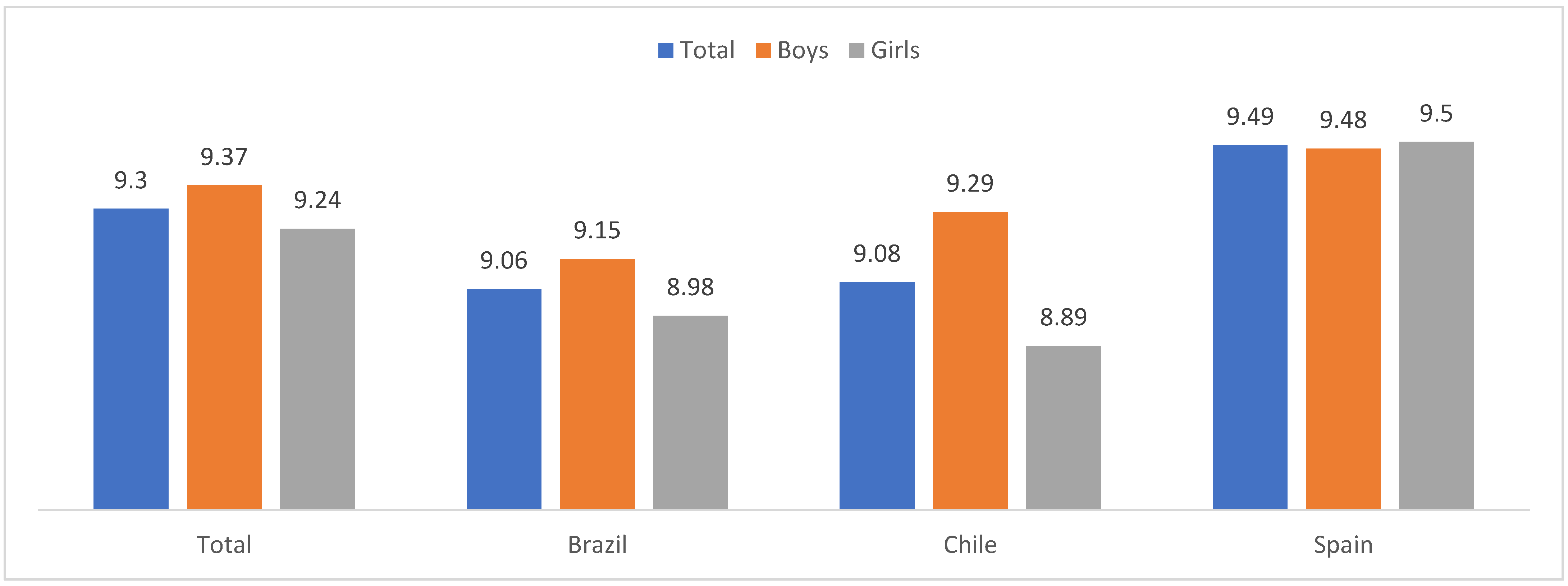

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Linear Regression Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Echazarreta, R.R.; Maulini, C.; Migliorati, M.; Isidori, E. Adolescencia y estilo de vida. Estudio del ocio de los escolares de la provincia de Roma. Pedagog. Soc. Rev. Interuniv. 2016, 28, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Baya, D.; Sarmento, H.; Nicoletti, J.A.; Garcia-Moro, F.J. Cross-Sectional Associations between Playing Sports or Electronic Games in Leisure Time and Life Satisfaction in 12-Year-Old Children from the European Union. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2022, 12, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldeleklioğlu, J. Predictive Effects of Subjective Happiness, Forgiveness, and Rumination on Life Satisfaction. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2015, 43, 1563–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, A.S.; Ng, J.Y.Y.; Lonsdale, C.; Lubans, D.R.; Ng, F.F. Promoting physical activity in children through family-based intervention: Protocol of the “Active 1 + FUN” randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030: More Active People for a Healthier World; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Kelly, P.; Matthews, A.; Foster, C. Young and Physically Active: A Blueprint for Making Physical Activity Appealing to Youth; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012.

- Bender, T.A. Assessment of Subjective Well-Being during Childhood and Adolescence. In Handbook of Classroom Assessment; Elsevier: San Diego, CA, USA, 1996; pp. 199–225. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, J.; Yoo, J.P. Patterns of Time Use among 12-Year-Old Children and Their Life Satisfaction: A Gender and Cross-Country Comparison. Child Ind. Res. 2022, 15, 1693–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, R.W.; Verma, S. How children and adolescents spend time across the world: Work, play, and developmental opportunities. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 701–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHale, S.M.; Crouter, A.C.; Tucker, C.J. Free-time activities in middle childhood: Links with adjustment in early adolescence. Child Dev. 2001, 72, 1764–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Oishi, S.; Lucas, R.E. Personality, culture, and subjective well being: Emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2003, 54, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofheinz Giacomoni, C.; de Souza, L.K.; Hutz, C.S. Eventos de Vida Positivos e Negativos em Crianças. Temas Psicol. 2016, 24, 1421–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Salvador, R.; Ortega, C. (Eds.) Ocio e innovación: De la mejora a la transformación. In Ocio e Innovación para un Compromiso Social, Responsable y Sostenible; Documentos de Estudio de Ocio, 47; Universidad de Deusto: Bilbao, Spain, 2012; pp. 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ángel, H.; Oliva, A.; Ángel, M. Diferencias de género en los estilos de vida de los adolescentes. Psychosoc. Interv. 2013, 22, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Campo-Ternera, L.; Herazo-Beltrán, Y.; García-Puello, F.; Suarez-Villa, M.; Méndez, O.; Vásquez de la Hoz, F. Estilos de vida saludables de niños, niñas y adolescentes. Salud Uninorte 2017, 33, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.; Picazo, C.; Gamboa, J.P. Análisis de la felicidad durante el tiempo libre: El papel de la conducta prosocial y material. Divers. Perspect. Psicol. 2020, 16, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarur Elsaca, D. La Felicidad y Los Bienes Exteriores: Una Aproximación Crítica a Partir de Aristóteles y la Economía Contemporánea. Ph.D. Thesis, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile, 2019. Available online: http://repositorio.uc.cl/xmlui/handle/11534/26384 (accessed on 3 May 2022).

- Cabrera-Darias, M.E.; Marrero-Quevedo, R.J. Motivos, personalidad y bienestar subjetivo en el voluntariado. An. Psicol. 2015, 31, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebherr, M.; Kohler, M.; Brailovskaia, J.; Brand, M.; Antons, S. Screen Time and Attention Subdomains in Children Aged 6 to 10 Years. Children 2022, 9, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochaíta, E.; Espinosa, M.A.; Gutiérrez, H. Adolescentes digitales. Rev. Estud. Juv. 2011, 92, 87–110. [Google Scholar]

- Booker, C.I.; Skew, A.J.; Kelly, Y.J.; Sacker, A. Media use, sports participation, and well-being in adolescence: Cross-sectional findings from the UK household longitudinal study. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 1105, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathers, M.; Canterford, L.; Olds, T.; Hesketh, K.; Ridley, K.; Wake, M. Electronic media use and adolescent health and well-being: Cross-sectional community study. Acad. Pediatr. 2009, 9, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svensson, R.; Oberwittler, D. It’s not the time they spend, it’s what they do: The interaction between delinquent friends and unstructured routine activity on delinquency: Findings from two countries. J. Crim. Justice 2010, 38, 1006–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, C.; Ison, M. What makes you happy? Appreciating the reasons that bring happiness to Argentine children living in vulnerable social contexts. J. Lat./Lat. Am. Stud. 2014, 6, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maftei, A.; Holman, A.C.; Cârlig, E.R. Does your child think you’re happy? Exploring the associations between children’s happiness and parenting styles. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 115, 105074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Kahneman, D.; Krueger, A.B.; Schkade, D.A.; Schwarz, N.; Stone, A.A. A survey method for characterizing daily life experience: The day reconstruction method. Science 2004, 306, 1776–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyes, C.L.; Shmotkin, D.; Ryff, C.D. Optimizing well-being: The empirical encounter of two traditions. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, D.; Montserrat, C.; Malo, S.; Gonzàlez, M.; Casas, F.; Crous, G. Subjective well-being: What do adolescents say? Child Fam. Soc. Work 2017, 22, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamama, L.; Arazi, Y. Aggressive behaviour in at-risk children: Contribution of subjective well-being and family cohesion. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2012, 17, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lietz, P.; Dix, K.L.; Tarabashkina, L.; O’Grady, E.; Ahmed, S.K. Family fun: A vital ingredient of early adolescents having a good life. J. Fam. Stud. 2020, 26, 459–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D.T. Psychological well-being, school adjustment, and problem behavior among Chinese adolescent boys from poor families: Does family functioning matter. In Adolescent Boys: Exploring Diverse Cultures of Boyhood; Way, N., Chu, J.Y., Eds.; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 129–143. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban-Gonzalo, S.; Esteban-Gonzalo, L.; Cabanas-Sánchez, V.; Miret, M.; Veiga, O.L. The Investigation of Gender Differences in Subjective Wellbeing in Children and Adolescents: The UP&DOWN Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gracia, P.; Garcia-Roman, J.; Oinas, T.; Anttila, T. Child and adolescent time use: A cross-national study. J. Marriage Fam. 2020, 82, 1304–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auhuber, L.; Vogel, M.; Grafe, N.; Kiess, W.; Poulain, T. Leisure Activities of Healthy Children and Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta, B.; Bronikowska, M.; Tomczak, M.; Laudańska-Krzemińska, I.; Bronikowski, M. Family leisure-time physical activities–results of the “Juniors for Seniors” 15-week intervention programme. Biomed. Hum. Kinet. 2017, 9, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, K.A.; Dustin, D.L. Towards a model of optimal family leisure. Ann. Leis. Res. 2015, 18, 180–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, L.; Mullan, K. Parental leisure time: A gender comparison in five countries. Soc. Politics 2013, 20, 329–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, C.; Bucksch, J.; Demetriou, Y.; Emmerling, S.; Linder, S.; Reimers, A.K. Considering sex/gender in interventions to promote children’s and adolescents’ leisure-time physical activity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Public Health 2022, 30, 2547–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Never | Less than Once a Week | Once or Twice a Week | Three or Four Days a Week | Five or Six Days a Week | Every Day | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Helping around the house | Brazil | 9.1 | 15.8 | 16.8 | 9.1 | 11 | 38.2 |

| Chile | 6.6 | 10.1 | 18.3 | 18.6 | 14.9 | 31.5 | |

| Spain | 3.3 | 11.7 | 21.5 | 19.3 | 12.2 | 32.1 | |

| Taking care of siblings or others | Brazil | 39.8 | 11.8 | 8 | 6.6 | 4.7 | 29.1 |

| Chile | 33.4 | 11.1 | 8.9 | 6.4 | 8.3 | 31.8 | |

| Spain | 23.7 | 9.3 | 10.4 | 8.6 | 9.1 | 39 | |

| Doing extra classes/tuition | Brazil | 67.5 | 6.3 | 9.6 | 4.7 | 2 | 10 |

| Chile | 80 | 5.9 | 4.6 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 4 | |

| Spain | 61.3 | 5.7 | 18.7 | 3.7 | 3.3 | 7.3 | |

| Doing homework/studying | Brazil | 7 | 10.8 | 8.8 | 10.5 | 12.6 | 50.3 |

| Chile | 6.3 | 7.2 | 15 | 16.3 | 18.9 | 36.2 | |

| Spain | 1.5 | 2.8 | 9.3 | 12.5 | 13.8 | 60.2 | |

| Watching TV | Brazil | 4.6 | 7.7 | 6.9 | 6.5 | 8.9 | 65.4 |

| Chile | 3.8 | 5.2 | 7.8 | 11.8 | 13.1 | 58.3 | |

| Spain | 2.6 | 5.1 | 11.3 | 12.5 | 13.8 | 54.8 | |

| Playing sports/doing exercise | Brazil | 18.6 | 13.3 | 17.2 | 12 | 8.9 | 29.9 |

| Chile | 8.9 | 6.3 | 11.4 | 16.3 | 17.2 | 40 | |

| Spain | 4.7 | 5.3 | 22 | 21.8 | 12.7 | 33.5 | |

| Relaxing with family | Brazil | 7.2 | 11 | 11.1 | 9.8 | 10.4 | 50.4 |

| Chile | 4 | 6.3 | 7.7 | 12.3 | 16.3 | 53.4 | |

| Spain | 2.9 | 6.3 | 12.5 | 10.2 | 16 | 52.1 | |

| Playing/time outside | Brazil | 10.4 | 14 | 11 | 10.7 | 12.7 | 41.3 |

| Chile | 10.5 | 12.4 | 13.6 | 15 | 15.1 | 33.4 | |

| Spain | 3.4 | 8.4 | 15.6 | 14.6 | 18.4 | 39.7 | |

| Using social media | Brazil | 16.7 | 7.8 | 7 | 7.8 | 6.7 | 53.9 |

| Chile | 12.5 | 6.7 | 9.1 | 10.6 | 15.7 | 45.4 | |

| Spain | 16.7 | 10.1 | 14.5 | 13.3 | 13.9 | 31.4 | |

| Playing electronic games | Brazil | 12.5 | 8.3 | 8.7 | 8.2 | 10 | 52.4 |

| Chile | 10.5 | 8.4 | 11.8 | 11.8 | 14.6 | 42.9 | |

| Spain | 14.1 | 13 | 18.9 | 14.3 | 11.5 | 28.2 |

| Never | Less than Once a Week | Once or Twice a Week | Three or Four Days a Week | Five or Six Days a Week | Every Day | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Helping around the house | Total | 5.4 | 12.2 | 19.7 | 16.8 | 12.5 | 33.4 |

| Boys | 7 | 12.4 | 18.6 | 18.1 | 13 | 30.9 | |

| Girls | 3.8 | 12.1 | 20.6 | 15.4 | 12.2 | 35.8 | |

| Taking care of siblings or others | Total | 29.6 | 10.3 | 9.5 | 7.6 | 7.9 | 35 |

| Boys | 29.4 | 9.8 | 9.1 | 8.4 | 8.7 | 34.5 | |

| Girls | 29.8 | 10.8 | 9.8 | 6.9 | 7.2 | 35.5 | |

| Doing extra classes/tuition | Total | 67.1 | 5.9 | 13.3 | 3.7 | 2.9 | 7.1 |

| Boys | 66.4 | 5.9 | 13.5 | 3.5 | 3.1 | 7.6 | |

| Girls | 67.5 | 5.8 | 13.3 | 3.9 | 2.7 | 6.8 | |

| Doing homework/studying | Total | 3.9 | 5.6 | 10.5 | 12.9 | 14.7 | 52.3 |

| Boys | 5.1 | 6.3 | 11.5 | 14 | 15.2 | 47.9 | |

| Girls | 2.7 | 5 | 9.7 | 11.7 | 14.3 | 56.6 | |

| Watching TV | Total | 3.3 | 5.7 | 9.4 | 11 | 12.5 | 58 |

| Boys | 2.9 | 4.4 | 8.2 | 10.6 | 12.5 | 61.3 | |

| Girls | 3.8 | 6.9 | 10.5 | 11.4 | 12.5 | 55 | |

| Playing sports/doing exercise | Total | 8.8 | 7.3 | 18.4 | 18.3 | 12.9 | 34.2 |

| Boys | 7.5 | 5.4 | 16.1 | 18.5 | 12.9 | 39.5 | |

| Girls | 9.9 | 9.1 | 20.6 | 18.1 | 12.8 | 29.4 | |

| Relaxing with family | Total | 4.1 | 7.4 | 11.1 | 10.6 | 14.8 | 52 |

| Boys | 4.1 | 6.4 | 11.5 | 11.3 | 16 | 50.6 | |

| Girls | 4.1 | 8.2 | 10.5 | 10.1 | 13.6 | 53.5 | |

| Playing/time outside | Total | 6.6 | 10.6 | 14.1 | 13.8 | 16.3 | 38.6 |

| Boys | 6.5 | 9.1 | 12.9 | 15 | 16.9 | 39.6 | |

| Girls | 6.7 | 11.7 | 15.1 | 12.6 | 15.9 | 38 | |

| Using social media | Total | 15.7 | 8.8 | 11.5 | 11.4 | 12.6 | 39.8 |

| Boys | 17.4 | 7.8 | 10.9 | 12.1 | 12 | 39.9 | |

| Girls | 14.3 | 9.9 | 12.1 | 10.7 | 13.2 | 39.8 | |

| Playing electronic games | Total | 12.9 | 10.9 | 14.9 | 12.3 | 11.9 | 37.1 |

| Boys | 5.3 | 5.8 | 14.8 | 15.4 | 12.9 | 45.8 | |

| Girls | 20.1 | 15.5 | 14.8 | 9.5 | 11 | 29.1 |

| Total F = 29.71 *** R2 = 0.096 | Boys F = 9.06 *** R2 = 0.054 | Girls F = 24.55 *** R2 = 0.133 | Brazil F = 8.55 *** R2 = 0.097 | Chile F = 13.21 *** R2 = 0.149 | Spain F = 9.83 *** R2 = 0.054 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t | β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t | β | |

| Country | 4.83 | 0.09 *** | 3.18 | 0.08 ** | 3.58 | 0.09 *** | ||||||

| Gender | −2.89 | −0.05 ** | −0.69 | −0.03 | −2.56 | −0.09 * | −1.99 | −0.05 * | ||||

| Helping around the house | 1.87 | −0.04 | 0.41 | 0.01 | 2.33 | 0.06 * | −0.04 | −0.01 | 1.88 | 0.07 | 1.40 | 0.04 |

| Taking care of siblings or others | −1.83 | −0.03 | −0.50 | −0.01 | −1.94 | −0.05 | −0.97 | −0.04 | −1.75 | −0.06 | −0.72 | −0.02 |

| Doing extra classes/tuition | −3.52 | −0.06 *** | −1.77 | −0.05 | −3.00 | −0.07 ** | −2.04 | −0.07 * | −0.80 | −0.03 | −3.02 | −0.07 ** |

| Doing homework/studying | 3.45 | 0.06 ** | 2.31 | 0.06* | 2.75 | 0.07 ** | 0.41 | 0.02 | 1.02 | 0.04 | 3.81 | 0.10 *** |

| Watching TV | 1.59 | 0.03 | 0.84 | 0.02 | 1.60 | 0.04 | 4.05 | 0.15 *** | −0.73 | −0.03 | −1.13 | −0.03 |

| Playing sports/doing exercise | 1.64 | 0.03 | 0.39 | 0.01 | 1.74 | 0.04 | 0.45 | 0.02 | 1.59 | 0.06 | 0.92 | 0.02 |

| Relaxing with family | 10.18 | 0.20 *** | 4.32 | 0.13 *** | 9.54 | 0.25 *** | 5.16 | 0.22 *** | 7.64 | 0.31 *** | 5.46 | 0.15 *** |

| Playing/time outside | 4.11 | 0.08 *** | 3.21 | 0.10 ** | 2.70 | 0.07 ** | 1.52 | 0.06 | 1.35 | 0.06 | 2.67 | 0.07 ** |

| Using social media | −1.43 | −0.03 | −2.10 | −0.06 * | 0.22 | 0.01 | −2.35 | −0.09 * | −0.76 | −0.03 | 0.88 | 0.02 |

| Playing electronic games | −1.62 | −0.03 | 0.87 | 0.03 | −2.79 | −0.08 ** | −0.74 | −0.03 | 0.37 | 0.02 | −1.98 | −0.06 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gomez-Baya, D.; Gaspar, T.; Corrêa, R.; Nicoletti, J.A.; Garcia-Moro, F.J. Leisure Time Activities and Subjective Happiness in Early Adolescents from Three Ibero-American Countries: The Cases of Brazil, Chile and Spain. Children 2023, 10, 1058. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061058

Gomez-Baya D, Gaspar T, Corrêa R, Nicoletti JA, Garcia-Moro FJ. Leisure Time Activities and Subjective Happiness in Early Adolescents from Three Ibero-American Countries: The Cases of Brazil, Chile and Spain. Children. 2023; 10(6):1058. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061058

Chicago/Turabian StyleGomez-Baya, Diego, Tania Gaspar, Rafael Corrêa, Javier Augusto Nicoletti, and Francisco Jose Garcia-Moro. 2023. "Leisure Time Activities and Subjective Happiness in Early Adolescents from Three Ibero-American Countries: The Cases of Brazil, Chile and Spain" Children 10, no. 6: 1058. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061058

APA StyleGomez-Baya, D., Gaspar, T., Corrêa, R., Nicoletti, J. A., & Garcia-Moro, F. J. (2023). Leisure Time Activities and Subjective Happiness in Early Adolescents from Three Ibero-American Countries: The Cases of Brazil, Chile and Spain. Children, 10(6), 1058. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061058