Analyses of Criminal Judgments about Domestic Child Abuse Cases in Taiwan

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Child factors:

- Perpetrator factors:

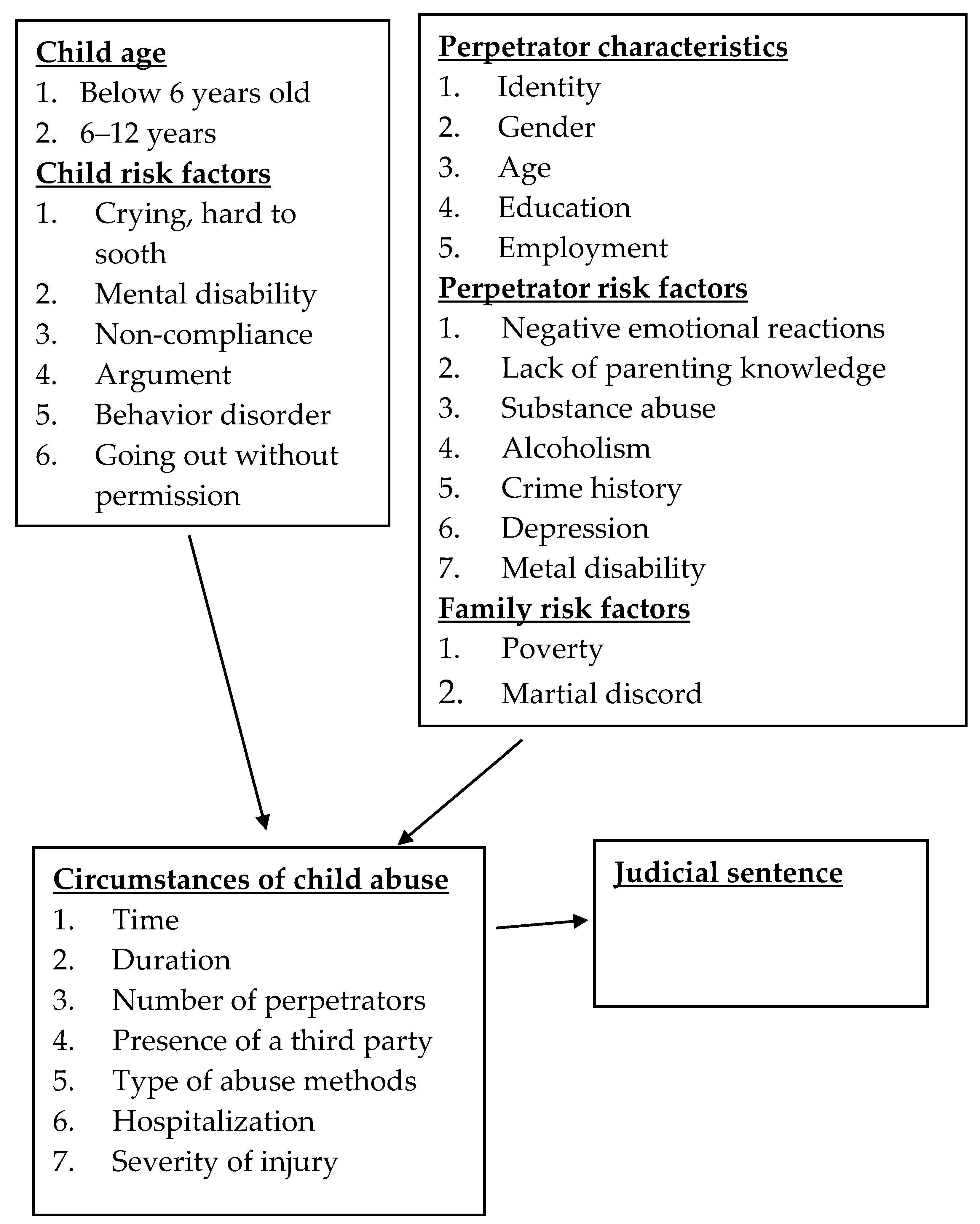

- To describe factors related to child abuse in judicial judgments, including child characteristics (age), child risk factors, perpetrator characteristics (identity, gender, age, education, employment, perpetrator risk factors such as negative emotions, lack of parenting knowledge, substance abuse, crime history, depression, mental disability), and family risk factors (poverty, marital discord).

- To describe the circumstances of child abuse, including the time of occurrence, duration of abuse, number of perpetrators, presence of a third party, type of abuse, hospitalization of victims, and the severity of injury sustained by the victims.

- To examine the sentences of perpetrators in relation to the severity of child abuse in judicial judgments of child abuse cases.

- Definition of Terminology

2. Materials and Methods

- Theoretical Framework:

3. Results

3.1. Factors Related to Domestic Child Abuse

3.1.1. Child Factors

3.1.2. Perpetrator Factors

3.1.3. Family Risk Factors

3.2. Circumstances of Child Abuse in Cases of Domestic Violence

3.2.1. Time

3.2.2. Duration

3.2.3. Number of Defendants

3.2.4. Presence of a Third Party

3.2.5. Type of Child Abuse

3.2.6. Hospitalization

3.2.7. Severity of Injury

3.3. Judicial Sentence of Child Abuse Perpetrators

4. Discussion

4.1. Factors Related to Domestic Child Abuse

4.1.1. Child Factors

4.1.2. Perpetrator Characteristics

4.1.3. Family Risk Factors

4.2. Circumstances of Child Abuse in Cases of Domestic Violence

4.3. Judicial Sentence of Child Abuse Perpetrators

5. Conclusions

- Limitations and future research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Palusci, V.J. Current Issues in Physical Abuse. In Handbook of Child Maltreatment; Child Maltreatment; Krugman, R.D., Korbin, J.E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Child Maltreatment (Child Abuse). Available online: https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/child/en/ (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Taiwan Data from Ministry of Health and Welfare. 2019. Available online: https://dep.mohw.gov.tw/DOS/lp-2985-113.html (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Wang, D.-S.; Chung, C.-H.; Chang, H.-A.; Kao, Y.-C.; Chua, D.-M.; Wang, C.-C.; Chen, S.-J.; Tzeng, N.-S.; Chien, W.-C. Association between child abuse exposure and the risk of psychiatric disorders: A nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 101, 104362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.-K.; Pan, Z.; Wang, L.-C. Parental Beliefs and Actual Use of Corporal Punishment, School Violence and Bullying, and Depression in Early Adolescence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, L.-L.; Chi, Y.-C.; Wu, C.-L. Child abuse and prevention networks. Taipei City Med. J. 2007, 4, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubbels, J.; Assink, M.; Prinzie, P.; van der Put, C.E. What Works in School-Based Programs for Child Abuse Prevention? The Perspectives of Young Child Abuse Survivors. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidman, R.; Smith, D.; Piccolo, L.R.; Kohler, H.P. Psychometric evaluation of the adverse childhood experience international questionnaire (ACE-IQ) in malawian adolescents. Child Abus. Negl. 2019, 92, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christakis, D.A. Focusing on the smaller adverse childhood experiences: The overlooked importance of aces. JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 170, 725–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J.; Torbey, S. Child maltreatment and psychosis. Neurobiol. Disease 2019, 131, 104378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widom, C.S. Longterm Consequences of Childhood Maltreatment. In Handbook of Child Maltreatment; Child Maltreatment; Krugman, R.D., Korbin, J.E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am. Psychol. 1977, 32, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giardino, A.P.; Giardino, E.R.; Isaac, R. Child Maltreatment and Disabilities: Increased Risk? In Handbook of Child Maltreatment; Child Maltreatment; Krugman, R.D., Korbin, J.E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridings, L.E.; Beasley, L.O.; Silovsky, J.F. Consideration of Risk and Protective Factors for Families at Risk for Child Maltreatment: An Intervention Approach. J. Fam. Violence 2017, 32, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The Social-Ecological Model: A Framework for Prevention. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention, 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/publichealthissue/social-ecologicalmodel.html (accessed on 5 July 2023).

- Chang, Y.-C.; Huang, J.-L.; Hsia, S.-H.; Lin, K.-L.; Lee, E.-P.; Chou, I.-J.; Hsin, Y.-C.; Lo, F.-S.; Wu, C.-T.; Chiu, C.-H.; et al. Prevention Protection Against Child Abuse Neglect (PCHAN) Study Group.Child protection medical service demonstration centers in approaching child abuse and neglect in Taiwan. Medicine 2016, 95, e5218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, G.S.K. Risk Factors of Subsequent Allegations of Child Maltreatment (Order No. 28648614). Available from Social Science Premium Collection. (2572573606). 2021. Available online: https://cyut.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/risk-factors-subsequent-allegations-child/docview/2572573606/se-2 (accessed on 5 July 2023).

- Kożybska, M.; Giezek, M.; Zabielska, P.; Masna, B.; Ciechowicz, J.; Paszkiewicz, M.; Kotwas, A.; Karakiewicz, B. Co-occurrence of adult abuse and child abuse: Analysis of the phenomenon. J. Inj. Violence Res. 2022, 14, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spearman, K.J.; Alhusen, J.L.; Ho, G.W.K.; Smith, K.F.; Campbell, J.C. Addressing Intimate Partner Violence and Child Maltreatment: Challenges and Opportunities. In Handbook of Child Maltreatment; Child Maltreatment; Krugman, R.D., Korbin, J.E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straus, M.A.; Kantor, G.K. Stress & child abuse. In The Battered Child; Helfer, R.E., Kempe, R.S., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Miragoli, S.; Balzarotti, S.; Camisasca, E.; Di Blasio, P. Parents’ perception of child behavior, parenting stress, and child abuse potential: Individual and partner influences. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 84, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Merritt, D.H. Familial financial stress and child internalizing behaviors: The roles of caregivers’ maltreating behaviors and social services. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 86, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlak, A.J.; Heaton, L.; Evans, M. Trends in Child Abuse Reporting. In Handbook of Child Maltreatment; Child Maltreatment; Krugman, R.D., Korbin, J.E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, B.; Jonson-Reid, M.; Dvalishvili, D. Poverty and Child Maltreatment. In Handbook of Child Maltreatment; Child Maltreatment; Krugman, R.D., Korbin, J.E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.D.; Anderson, K.E.; Garnett, M.L.; Hill, E.M. Economic instability and household chaos relate to cortisol for children in poverty. J. Fam. Psychol. 2019, 33, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, C.A.; Fleegler, E.W.; Monuteaux, M.C.; Wilson, C.R.; Christian, C.W.; Lee, L.K. Community poverty and child abuse fatalities in the United States. Pediatrics 2017, 139, e20161616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afifi, T.O. Child abuse and adolescent parenting: Developing a theoretical model from an ecological perspective. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2007, 14, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Brooks-Gunn, J. Correlates and consequences of harsh discipline for young children. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 1997, 151, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Cohen, P.; Johnson, J.; Salzinger, S. A longitudinal analysis of risk factors for child maltreatement: Findings of a 17-year prospective study of officially recorded and self-reported child abuse and neglect. Child Abus. Negl. 1998, 22, 1065–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtin, E.; Allchin, E.; Ding, A.J.; Layte, R. The role of socioeconomic interventions in reducing exposure to adverse childhood experiences: A systematic review. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2019, 6, 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.Y.; Maguire-Jack, K.; Showalter, K.; Kim, Y.K.; Slack, K.S. Child care subsidy and child maltreatment. Child Fam. Soc. Work. 2019, 24, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepple, N.J.; Wolf, J.P.; Freisthler, B. Substance Use and Child Maltreatment: Providing a Framework for Understanding the Relationship Using Current Evidence. In Handbook of Child Maltreatment; Child Maltreatment; Krugman, R.D., Korbin, J.E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stith, S.M.; Liu, T.; Davies, L.C.; Boykin, E.L.; Alder, M.C.; Harris, J.M.; Som, A.; McPherson, M.; Dees, J.E.M.E.G. Risk factors in child maltreatment: A meta-analytic review of the literature. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2009, 14, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, D.A.; Heyman, R.E.; Slep, A.M.S. Risk factors for child physical abuse. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2001, 6, 121–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freisthler, B.; Kepple, N.J. Types of substance use and punitive parenting: A preliminary exploration. J. Soc. Work. Pract. Addict. 2019, 19, 262–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radhakrishna, A.; Bou-Saada, I.E.; Hunter, W.M.; Catellier, D.M.; Kotch, J.B. Are father surrogates a risk factor for child maltreatment? Child Maltreatment 2001, 6, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, K.L.; Chen, M.; Lo, C.K.M.; Chen, X.Y.; Tang, D.; Ip, P. Who Is at High Risk for Child Abuse and Neglect: Risk Assessment among Battered Women Using Shelter Services. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, M.; Piel, M.H.; Simon, M. Child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic: Consequences of parental job loss on psychological and physical abuse towards children. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 110, 104709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.A. Social Networks and Child Maltreatment. In Handbook of Child Maltreatment; Child Maltreatment; Krugman, R.D., Korbin, J.E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimbrough-Melton, R. Child Maltreatment as a Problem in International Law. In Handbook of Child Maltreatment; Child Maltreatment; Krugman, R.D., Korbin, J.E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-S.; Cheng, C.-L.; Chien, S.-C. The relationships among young children’s emotional regulation strategy, parental reaction, and temperament. Bulletin of Educational Psychology 2008, 40, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.-H. Giving Children a Chance to Grow—Concepts, Challenges, and Suggestions Related to Child Abuse. New Soc. Taiwan 2019, 63, 69–79. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Shen, C.-T. Punish parents and save children? Outcome evaluation of mandatory parenting counseling in Taiwan: Child abuse re-reporting rate as an indicator. J. Soc. Policy Soc. Work. 2018, 22, 97–133. Available online: https://scholars.lib.ntu.edu.tw/handle/123456789/408463?mode=full (accessed on 5 July 2023). (In Chinese).

- Pai, L.-F. Case Study: Taiwan’s Child Abuse and Neglect Prevention: The Child and Youth High-Risk Family Program. Child Welf. Suppl. Spec. Issue Glob. Perspect. Child Prot. Negl. 2021, 98, 227–241. Available online: https://cyut.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/case-study-taiwans-child-abuse-neglect-prevention/docview/2509376910/se-2 (accessed on 5 July 2023).

- Sawant, T.; Dsilva, C. Children victims of marital conflict: Impact and interventions. IAHRW Int. J. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2020, 8, 215–218. Available online: https://cyut.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/children-victims-marital-conflict-impact/docview/2617209352/se-2 (accessed on 5 July 2023).

- Liu, S.-C. System debugging? Individual blame? Serious case reviews of child maltreatment fatalities in Taiwan. NTU Soc. Work. Rev. 2021, 44, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Death | Severely Injuried | Mildly Injuried | n/% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological mother | 20 | 2 | 7 | 29/31.9% |

| Biological father | 17 | 2 | 7 | 26/28.6% |

| Cohabiting partner | 13 | 4 | 2 | 19/20.9% |

| Relative | 6 | 1 | 3 | 10/11% |

| Step-father | 0 | 3 | 1 | 4/4.4% |

| Step-mother | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3/3.3% |

| Total | 57 | 13 | 21 | 91/100% |

| Frequency and Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|

| Risk Factors | Frequency/N | Percentage |

| Negative emotional responses | 77/91 | 84.6% |

| Lack of parenting education | 62/91 | 68.1% |

| Depression | 14/91 | 15.4% |

| Crime history | 13/91 | 14.3% |

| Substance abuse | 10/91 | 11.0% |

| Alcoholism | 10/91 | 11.0% |

| Mental disabililty | 5/91 | 5.5% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Su, H.-C.; Lin, Y.-H. Analyses of Criminal Judgments about Domestic Child Abuse Cases in Taiwan. Children 2023, 10, 1237. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10071237

Su H-C, Lin Y-H. Analyses of Criminal Judgments about Domestic Child Abuse Cases in Taiwan. Children. 2023; 10(7):1237. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10071237

Chicago/Turabian StyleSu, Hsiu-Chih, and Yi-Hxuan Lin. 2023. "Analyses of Criminal Judgments about Domestic Child Abuse Cases in Taiwan" Children 10, no. 7: 1237. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10071237

APA StyleSu, H.-C., & Lin, Y.-H. (2023). Analyses of Criminal Judgments about Domestic Child Abuse Cases in Taiwan. Children, 10(7), 1237. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10071237