Why Are Child and Youth Welfare Support Services Initiated? A First-Time Analysis of Administrative Data on Child and Youth Welfare Services in Austria

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Data Collection Procedure

- Parental support: This form of support is indicated if there is a risk to the well-being of the child, but it can be prevented by the use of the chosen support measure while remaining in the family or the child’s other previous environment. It should primarily serve to improve the conditions for ensuring the child’s well-being in the family or their previous environment. The category of parental support includes various support services provided by people from outside the family and from different professional groups (e.g., social workers, psychologists, pedagogues, psychotherapists, and pediatric nurses), such as family intensive care, youth intensive care, or afternoon care, which are based on the families’ and children’s individual needs.

- Care home: Care homes are the intervention of choice when, based on the risk assessment, there is a risk to the well-being of the child or adolescent concerned that can only be averted by caring for the affected child or adolescent outside the family or other previous environment. In Lower Austria, these children are living in communities of groups, where a team of professional pedagogues takes care of them.

- Foster family: Accommodation in a foster family is an alternative to care homes. It is granted if, due to the age of the child and the problem situation, a suitable foster family can be found.

- Kinship care: In this form of care, the child or adolescent is raised by a grandparent or other close family member with whom the child or adolescent has a close relationship.

2.3. Data Analysis Procedures

3. Results

3.1. Support Services

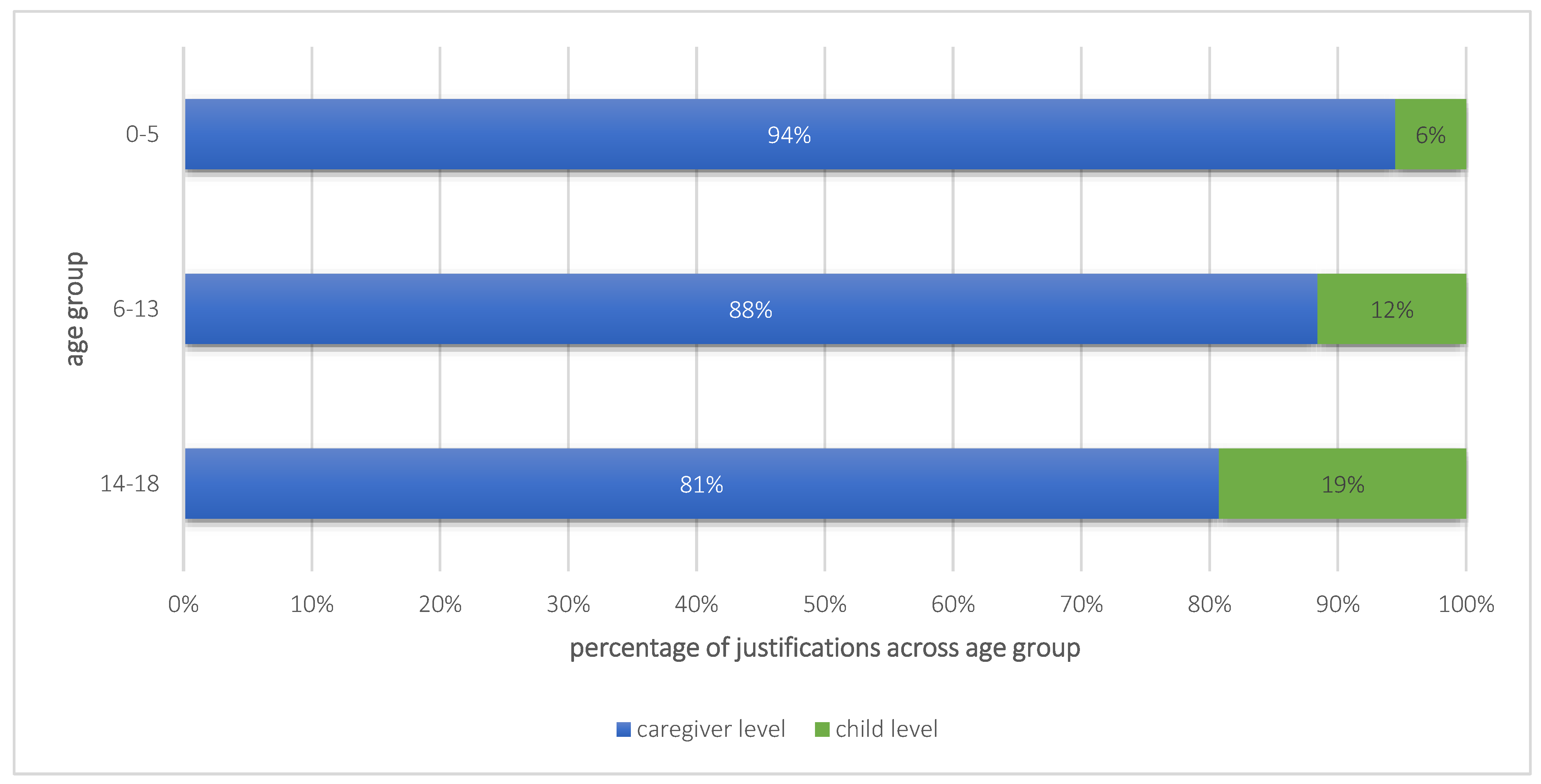

3.2. Support Service Justifications

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Engler, A.D.; Sarpong, K.O.; Van Horne, B.S.; Greeley, C.S.; Keefe, R.J. A systematic review of mental health disorders of children in foster care. Trauma Violence Abus. 2022, 23, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jäggi, L.; Jaramillo, J.; Drazdowski, T.K.; Seker, S. Child welfare involvement and adjustment among care alumni and their children: A systematic review of risk and protective factors. Child. Abuse Negl. 2022, 131, 105776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullen, P.E.; Martin, J.L.; Anderson, J.C.; Romans, S.E.; Herbison, G.P. The long-term impact of the physical, emotional, and sexual abuse of children: A community study. Child. Abuse Negl. 1996, 20, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, D.J. The importance of degree versus type of maltreatment: A cluster analysis of child abuse types. J. Psychol. 2004, 138, 303–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, D.J.; McCabe, M.P. Relationships between different types of maltreatment during childhood and adjustment in adulthood. Child Maltreat. 2000, 5, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bundesgesetz über die Grundsätze für Hilfen für Familien und Erziehungshilfen für Kinder und Jugendliche; Rechtsinformationssystem des Bundes: Vienna, Austria, 2013.

- Statistik Austria. Kinder und Jugendhilfe. Available online: https://www.statistik.at/statistiken/bevoelkerung-und-soziales/sozialleistungen/kinder-und-jugendhilfe (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Kinder und Jugendhilfebericht 2018–2021; Amt der Niederösterreichischen Landesregierung—Abteilung Kinder und Jugendhilfe: St. Pölten, Austria, 2022.

- Fallon, B.; Filippelli, J.; Black, T.; Trocmé, N.; Esposito, T. How can data drive policy and practice in child welfare? Making the link in Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- English, D.J.; Brandford, C.C.; Coghlan, L. Data-based organizational change: The use of administrative data to improve child welfare programs and policy. Child Welf. 2000, 79, 499–515. [Google Scholar]

- Green, B.L.; Ayoub, C.; Bartlett, J.D.; Furrer, C.; Von Ende, A.; Chazan-Cohen, R.; Klevens, J.; Nygren, P. It’s not as simple as it sounds: Problems and solutions in accessing and using administrative child welfare data for evaluating the impact of early childhood interventions. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2015, 57, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soneson, E.; Das, S.; Burn, A.-M.; van Melle, M.; Anderson, J.K.; Fazel, M.; Fonagy, P.; Ford, T.; Gilbert, R.; Harron, K.; et al. Leveraging administrative data to better understand and address child maltreatment: A scoping review of data linkage studies. Child Maltreat. 2022, 28, 176–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westad, C.; McConnell, D. Child welfare involvement of mothers with mental health issues. Community Ment. Health J. 2012, 48, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brattabø, I.V.; Bjørknes, R.; Åstrøm, A.N. Reasons for reported suspicion of child maltreatment and responses from the child welfare—A cross-sectional study of Norwegian public dental health personnel. BMC Oral. Health 2018, 18, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeZelar, S.; Lightfoot, E. Who refers parents with intellectual disabilities to the child welfare system? An analysis of referral sources and substantiation. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 119, 105639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, B.L.; Ayoub, C.; Bartlett, J.D.; Von Ende, A.; Furrer, C.; Chazan-Cohen, R.; Vallotton, C.; Klevens, J. The effect of Early Head Start on child welfare system involvement: A first look at longitudinal child maltreatment outcomes. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2014, 42, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Forrester, D.; Harwin, J. Parental substance misuse and child welfare: Outcomes for children two years after referral. Br. J. Soc. Work. 2008, 38, 1518–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dore, M.M.; Doris, J.M.; Wright, P. Identifying substance abuse in maltreating families: A child welfare challenge. Child Abus. Negl. 1995, 19, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, K. Child welfare involvement and contexts of poverty: The role of parental adversities, social networks, and social services. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 72, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loman, L.A.; Siegel, G.L. Effects of anti-poverty services under the differential response approach to child welfare. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 1659–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, W. Kinderschutz—Spannungsverhältnisse gestalten. In Kinderschutz. Risiken Erkennen, Spannungsverhätlnisse Gestalten; Suess, G.J., Hammer, W., Eds.; Klett-Cotta: Stuttgart, Germany, 2010; pp. 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Gerichtliche Kriminalstatistik; Statistik Austria: Vienna, Austria, 2022; pp. 1–120.

- Campbell, K.E.; Lee, B.A. Gender differences in urban neighboring. Sociol. Q. 1990, 31, 495–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilfus, M.E. From victims to survivors to offenders. Women Crim. Justice 1993, 4, 63–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffensmeier, D.; Allan, E. Gender and crime: Toward a gendered theory of female offending. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1996, 22, 459–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.M.; Fairman, B.; Gilreath; Xuan, Z.; Rothman, E.F.; Parnham; Furr-Holden, C.D.M. Past 15-year trends in adolescent marijuana use: Differences by race/ethnicity and sex. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015, 155, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Smith, D.A.; Paternoster, R. The gender gap in theories of deviance: Issues and evidence. J. Res. Crime Delinq. 1987, 24, 140–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Miller, S.L. Protective factors against juvenile delinquency: Exploring gender with a nationally representative sample of youth. Soc. Sci. Res. 2020, 86, 102376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, V.M.; McCloskey, L.A. Gender differences in the risk for delinquency among youth exposed to family violence. Child Abus. Negl. 2001, 25, 1037–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baidawi, S.; Papalia, N.; Featherston, R. Gender differences in the maltreatment-youth offending relationship: A scoping review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2023, 24, 1140–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.M.; Slotboom, A.-M.; Bijleveld, C.C. Risk factors for delinquency in adolescent and young adult females: A European review. Eur. J. Criminol. 2010, 7, 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leadbeater, B.J.; Kuperminc, G.P.; Blatt, S.J.; Hertzog, C. A multivariate model of gender differences in adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems. Dev. Psychol. 1999, 35, 1268–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, M.A.J.; Brotherhood, A.; Klein, C.; Priebe, B.; Schmutterer, I.; Schwarz, T. Bericht zur Drogensituation 2022; Gesundheit Österreich GmbH: Vienna, Austria, 2022; pp. 1–248. [Google Scholar]

- Hojni, M.; Delcour, J.; Strizek, J.; Uhl, A. ESPAD Österreich 2019; Gesundheit Österreich GmbH: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, R. Gender differences In adolescent drug use:The impact of parental monitoring and peer deviance. Youth Soc. 2003, 34, 300–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spigner, C.; Hawkins, W.E.; Loren, W. Gender differences in perception of risk associated with alcohol and drug use among college students. Women Health 1993, 20, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundesministerium für Soziales Gesundheit Pflege und Konsumentenschutz. Gewaltprävention: Mann Spricht’s An! Available online: https://www.sozialministerium.at/Themen/Soziales/Soziale-Themen/Geschlechtergleichstellung/Gewaltpraevention/mannsprichtsan.html (accessed on 26 June 2023).

- Kapella, O.; Baierl, A.; Rille-Pfeiffer, C.; Gserick, C.; Schmidt, E.-M.; Schröttle, M. Gewalt in der Familie und im Nahen Sozialen Umfeld; Österreichisches Institut für Familienforschung: Vienna, Austria, 2011; pp. 1–303. [Google Scholar]

- Moody, G.; Cannings-John, R.; Hood, K.; Kemp, A.; Robling, M. Establishing the international prevalence of self-reported child maltreatment: A systematic review by maltreatment type and gender. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cashmore, J.; Shackel, R. Gender differences in the context and consequences of child sexual abuse. Curr. Issues Crim. Justice 2014, 26, 75–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltenborgh, M.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; Alink, L.R.A.; van Ijzendoorn, M.H. The universality of childhood emotional abuse: A meta-analysis of worldwide prevalence. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2012, 21, 870–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaton, T.B. Marital stability throughout the child-rearing years. Demography 1990, 27, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, G. The Impact of children on divorce risks of swedish women. Eur. J. Popul./Rev. Eur. Démogr. 1997, 13, 109–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracher, M.; Santow, G.; Morgan, S.P.; Trussell, J. Marriage dissolution in Australia: Models and explanations. Popul. Stud. 1993, 47, 403–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Yu, J.; Qiu, Z. The impact of children on divorce risk. J. Chin. Sociol. 2015, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Waite, L.J.; Lillard, L.A. Children and marital disruption. Am. J. Sociol. 1991, 96, 930–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, I.; Verma, M.; Singh, T.; Gupta, V. Prevalence of behavioral problems in school going children. Indian J. Pediatr. 2001, 68, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Splett, J.W.; Garzona, M.; Gibson, N.; Wojtalewicz, D.; Raborn, A.; Reinke, W.M. Teacher recognition, concern, and referral of children’s internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. Sch. Ment. Health 2019, 11, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smokowski, P.R.; Bacallao, M.L.; Cotter, K.L.; Evans, C.B.R. The effects of positive and negative parenting practices on adolescent mental health outcomes in a multicultural sample of rural youth. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2015, 46, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, K.-H. Mediating effects of negative emotions in parent–child conflict on adolescent problem behavior. Asian J. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 14, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withers, M.C.; McWey, L.M.; Lucier-Greer, M. Parent–adolescent relationship factors and adolescent outcomes among high-risk families. Fam. Relat. 2016, 65, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobi, L.; Wagner, H.; Frühwirth-Schnatter, S. Bayesian treatment effects models with variable selection for panel outcomes with an application to earnings effects of maternity leave. J. Econom. 2016, 193, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbst-Debby, A.; Kaplan, A.; Endeweld, M.; Achouche, N. Adolescent employment, family income and parental divorce. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 2023, 84, 100772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assink, M.; van der Put, C.E.; Oort, F.J.; Stams, G.J.J.M. The development and validation of the Youth Actuarial Care Needs Assessment Tool for Non-Offenders (Y-ACNAT-NO). BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vial, A.; Assink, M.; Stams, G.J.J.M.; van der Put, C. Safety assessment in child welfare: A comparison of instruments. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 108, 104555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, A.; van der Put, C.; Stams, G.J.J.M.; Assink, M. The content validity and usability of a child safety assessment instrument. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 107, 104538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, A.; van der Put, C.; Stams, G.J.J.M.; Dinkgreve, M.; Assink, M. Validation and further development of a risk assessment instrument for child welfare. Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 117, 105047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, K.; Mason, W.; Bywaters, P.; Featherstone, B.; Daniel, B.; Brady, G.; Bunting, L.; Hooper, J.; Mirza, N.; Scourfield, J.; et al. Social work, poverty, and child welfare interventions. Child Fam. Soc. Work. 2018, 23, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cénat, J.M.; McIntee, S.-E.; Mukunzi, J.N.; Noorishad, P.-G. Overrepresentation of Black children in the child welfare system: A systematic review to understand and better act. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 120, 105714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, A.S.; Leeb, R.T.; English, D.; Graham, J.C.; Briggs, E.C.; Brody, K.E.; Marshall, J.M. What’s in a name? A comparison of methods for classifying predominant type of maltreatment. Child Abus. Negl. 2005, 29, 533–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Caregiver Level | Child Level |

|---|---|

| alcohol abuse of caregiver(s) | alcohol abuse of the child |

| violence between caregivers | violent behavior of the child |

| illness or death of caregiver(s) | illness of the child |

| parental overload | school problems or violation of compulsory attendance |

| delinquency of caregiver(s) | pregnancy of the minor |

| substance abuse of caregiver(s) | delinquency of the child |

| unfavorable economic conditions | substance abuse of the child |

| divorce or separation of caregiver(s) | behavioral issues |

| mental abuse of the child | |

| physical abuse of the child | |

| sexual abuse of the child | |

| child witnessing violence | |

| child neglect |

| Male | Female | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Justification | n | % | n | % | n |

| parental overload | 1338 | 56% | 1070 | 44% | 2408 |

| behavioral issues | 305 | 63% | 182 | 37% | 487 |

| difficult economic conditions | 230 | 52% | 212 | 48% | 442 |

| divorce or separation of caregiver(s) | 195 | 49% | 202 | 51% | 397 |

| illness or death of caregiver(s) | 134 | 47% | 154 | 53% | 288 |

| child neglect | 138 | 59% | 97 | 41% | 235 |

| physical abuse of the child | 53 | 55% | 43 | 45% | 96 |

| school problems | 53 | 57% | 40 | 43% | 93 |

| substance abuse of caregiver(s) | 53 | 60% | 35 | 40% | 88 |

| alcohol abuse of caregivers(s) | 39 | 48% | 42 | 52% | 81 |

| child witnessing violence | 35 | 52% | 32 | 48% | 67 |

| mental abuse of the child | 25 | 48% | 27 | 52% | 52 |

| violence between caregivers | 29 | 58% | 21 | 42% | 50 |

| sexual abuse of the child | 8 | 23% | 27 | 77% | 35 |

| delinquency of caregiver(s) | 12 | 50% | 12 | 50% | 24 |

| illness of the child | 10 | 50% | 10 | 50% | 20 |

| violent behavior of the child | 14 | 70% | 6 | 30% | 20 |

| delinquency of the child | 12 | 100% | 0 | 0% | 12 |

| substance abuse of the child | 6 | 60% | 4 | 40% | 10 |

| pregnancy of the minor | 2 | 25% | 6 | 75% | 8 |

| alcohol abuse of the child | 2 | 40% | 3 | 60% | 5 |

| total | 2693 | 55% | 2225 | 45% | 4918 |

| Parental Overload | Behavioral Issues | Difficult Economic Conditions | Divorce or Separation of Caregiver(s) | Death or Illness of Caregiver(s) | Child Neglect | Physical Abuse of the Child | School Problems | Substance Abuse of the Caregiver(s) | Alcohol Abuse of the Caregiver(s) | Child Witnessing Violence | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 0–5 | 381 | 56.95% | 25 | 3.74% | 71 | 10.61% | 31 | 4.63% | 39 | 5.83% | 38 | 5.68% | 4 | 0.60% | 4 | 0.60% | 27 | 4.04% | 11 | 1.64% | 11 | 1.64% |

| 6–13 | 1237 | 49.76% | 215 | 8.65% | 261 | 10.50% | 192 | 7.72% | 145 | 5.83% | 124 | 4.99% | 53 | 2.13% | 57 | 2.29% | 45 | 1.81% | 36 | 1.45% | 40 | 1.61% |

| 14–18 | 622 | 45.57% | 194 | 14.21% | 85 | 6.23% | 112 | 8.21% | 78 | 5.71% | 63 | 4.62% | 30 | 2.20% | 32 | 2.34% | 14 | 1.03% | 25 | 1.83% | 15 | 1.10% |

| not specified | 168 | 42.21% | 53 | 13.32% | 25 | 6.28% | 62 | 15.58% | 26 | 6.53% | 10 | 2.51% | 9 | 2.26% | 0 | 0.00% | 2 | 0.50% | 9 | 2.26% | 1 | 0.25% |

| total | 2408 | 48.96% | 487 | 9.90% | 442 | 8.99% | 397 | 8.07% | 288 | 5.86% | 235 | 4.78% | 96 | 1.95% | 93 | 1.89% | 88 | 1.79% | 81 | 1.65% | 67 | 1.36% |

| Mental abuse of the child | Violence between caregiver(s) | Sexual abuse of the child | Delinquency of caregiver(s) | Illness of the child | Violent behavior of the child | Delinquency of the child | Substance abuse of the child | Pregnancy of the minor | Alcohol abuse of the child | Total | ||||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | ||

| 0–5 | 1 | 0.15% | 12 | 1.79% | 4 | 0.60% | 2 | 0.30% | 2 | 0.30% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 6 | 0.90% | 0 | 0.00% | 669 | |

| 6–13 | 17 | 0.68% | 18 | 0.72% | 14 | 0.56% | 16 | 0.64% | 7 | 0.28% | 6 | 0.24% | 2 | 0.08% | 0 | 0.00% | 0 | 0.00% | 1 | 0.04% | 2486 | |

| 14–18 | 24 | 1.76% | 16 | 1.17% | 15 | 1.10% | 3 | 0.22% | 11 | 0.81% | 9 | 0.66% | 7 | 0.51% | 8 | 0.59% | 0 | 0.00% | 2 | 0.15% | 1365 | |

| not specified | 10 | 2.51% | 4 | 1.01% | 2 | 0.50% | 3 | 0.75% | 0 | 0.00% | 5 | 1.26% | 3 | 0.75% | 2 | 0.50% | 2 | 0.50% | 2 | 0.50% | 398 | |

| total | 52 | 1.06% | 50 | 1.02% | 35 | 0.71% | 24 | 0.49% | 20 | 0.41% | 20 | 0.41% | 12 | 0.24% | 10 | 0.20% | 8 | 0.16% | 5 | 0.10% | 4918 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haider, K.; Kaltschik, S.; Amon, M.; Pieh, C. Why Are Child and Youth Welfare Support Services Initiated? A First-Time Analysis of Administrative Data on Child and Youth Welfare Services in Austria. Children 2023, 10, 1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10081376

Haider K, Kaltschik S, Amon M, Pieh C. Why Are Child and Youth Welfare Support Services Initiated? A First-Time Analysis of Administrative Data on Child and Youth Welfare Services in Austria. Children. 2023; 10(8):1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10081376

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaider, Katja, Stefan Kaltschik, Manuela Amon, and Christoph Pieh. 2023. "Why Are Child and Youth Welfare Support Services Initiated? A First-Time Analysis of Administrative Data on Child and Youth Welfare Services in Austria" Children 10, no. 8: 1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10081376

APA StyleHaider, K., Kaltschik, S., Amon, M., & Pieh, C. (2023). Why Are Child and Youth Welfare Support Services Initiated? A First-Time Analysis of Administrative Data on Child and Youth Welfare Services in Austria. Children, 10(8), 1376. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10081376