Do My Reactions Outweigh My Actions? The Relation between Reactive and Proactive Aggression with Peer Acceptance in Preschoolers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Present Study

3. Method

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Ethical Considerations

4. Variables and Materials

4.1. Peer Acceptance

4.2. Reactive and Proactive Aggression

5. Statistical Analyses

6. Results

7. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ng-Knight, T.; Shelton, K.H.; Riglin, L.; Frederickson, N.; McManus, I.C.; Rice, F. ‘Best Friends Forever’? Friendship Stability across School Transition and Associations with Mental Health and Educational Attainment. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 89, 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, R.A.G.; van den Bedem, N.; Blijd-Hoogewys, E.M.A.; Stockmann, L.; Rieffe, C. Friendship Quality among Autistic and Non-Autistic (Pre-) Adolescents: Protective or Risk Factor for Mental Health? Autism 2022, 26, 2041–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engdahl, I. Doing Friendship during the Second Year of Life in a Swedish Preschool. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2012, 20, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howes, C. Patterns of Friendship. Child Dev. 1983, 54, 1041–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimond, F.A.; Altman, R.; Vitaro, F.; Brendgen, M.; Laursen, B. The Interchangeability of Liking and Friend Nominations to Measure Peer Acceptance and Friendship. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2022, 46, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucaba, K.; Monks, C.P. Peer Relations and Friendships in Early Childhood: The Association with Peer Victimization. Aggress. Behav. 2022, 48, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diesendruck, G.; Ben-Eliyahu, A. The Relationships among Social Cognition, Peer Acceptance, and Social Behavior in Israeli Kindergarteners. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2006, 30, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endedijk, H.M.; Cillessen, A.H.N.; Bekkering, H.; Hunnius, S. Cooperation and Preference by Peers in Early Childhood: A Longitudinal Study. Soc. Dev. 2020, 29, 854–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenseng, F.; Belsky, J.; Skalicka, V.; Wichstrøm, L. Preschool Social Exclusion, Aggression, and Cooperation: A Longitudinal Evaluation of the Need-to-Belong and the Social-Reconnection Hypotheses. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 40, 1637–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClain, C.M.; Elledge, L.C.; Manring, S.; Whitley, M.L.; Vernberg, E.M. Functions of Aggression and Peer Likeability in Elementary School Children across Time. J. Appl. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 38, 95–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltz, S.; Cillessen, A.H.N.; van den Berg, Y.H.M.; Gommans, R. Popularity Differentially Predicts Reactive and Proactive Aggression in Early Adolescence. Aggress. Behav. 2016, 42, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manring, S.; Christian Elledge, L.; Swails, L.W.; Vernberg, E.M. Functions of Aggression and Peer Victimization in Elementary School Children: The Mediating Role of Social Preference. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 2018, 46, 795–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, S.C.; Frazer, A.L.; Blossom, J.B.; Fite, P.J. Forms and Functions of Aggression in Early Childhood. J. Clin. Child. Adolesc. Psychol. 2018, 48, 790–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, K.J.; Ostrov, J.M. Testing a Higher Order Model of Internalizing and Externalizing Behavior: The Role of Aggression Subtypes. Child. Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2018, 49, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, R.E.; Vitaro, F.; Côté, S.M. Developmental Origins of Chronic Physical Aggression: A Bio-Psycho-Social Model for the Next Generation of Preventive Interventions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2018, 69, 383–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, R.E.; Nagin, D.S.; Séguin, J.R.; Zoccolillo, M.; Zelazo, P.D.; Boivin, M.; Pérusse, D.; Japel, C. Physical Aggression during Early Childhood: Trajectories and Predictors. Pediatrics 2004, 114, e43–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, S.; Vaillancourt, T.; LeBlanc, J.C.; Nagin, D.S.; Tremblay, R.E. The Development of Physical Aggression from Toddlerhood to Pre-Adolescence: A Nation Wide Longitudinal Study of Canadian Children. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 2006, 34, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, B.E.; Santos, A.J. Structural descriptions of social transactions among young children: Affiliation and dominance in preschool groups inter. In Transgenerational Transmission of Trauma in Portuguese Military Personnel View Project Sleep and Adaptation in Preschool Age Children View Project; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Girard, L.C.; Tremblay, R.E.; Nagin, D.; Côté, S.M. Development of Aggression Subtypes from Childhood to Adolescence: A Group-Based Multi-Trajectory Modelling Perspective. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 2019, 47, 825–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Peña, P.; Carrasco, M.; Del Barrio, V.; Gordillo Rodríguez, R. Analisys of Reactive and Proactive Aggression in Children from 2 to 6 Years Old. Rev. Iberoam. Diagnóstico Eval. Psicológica 2013, 1, 139–159. [Google Scholar]

- Crick, N.R.; Dodge, K.A. A Review and Reformulation of Social Information-Processing Mechanisms in Children’s Social Adjustment. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 115, 74–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, R.E.J.; van Dijk, A.; de Castro, B.O. A Dual-Mode Social-Information-Processing Model to Explain Individual Differences in Children’s Aggressive Behavior. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 10, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, B.O.; van Dijk, A. It’s gonna end up with a fight anyway. In The Wiley Handbook of Disruptive and Impulse-Control Disorders; Lochman, J.E., Matthys, W., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons (Wiley): Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 237–253. [Google Scholar]

- De Castro, B.O.; Merk, W.; Koops, W.; Veerman, J.W.; Bosch, J.D. Emotions in Social Information Processing and Their Relations with Reactive and Proactive Aggression in Referred Aggressive Boys. J. Clin. Child. Adolesc. Psychol. 2005, 34, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, E.T.; Greenberg, M.T.; Kusche, C.A. The Relations between Emotional Understanding, Intellectual Functioning, and Disruptive Behavior Problems in Elementary-School-Aged Children. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychol. 1994, 22, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, P.M.; Martin, S.E.; Dennis, T.A. Emotion Regulation as a Scientific Construct: Methodological Challenges and Directions for Child Development Research. Child Dev. 2004, 75, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, E.R. Head Start Parents’ Vocational Preparedness Indirectly Predicts Preschoolers’ Physical and Relational Aggression. Aggress. Behav. 2022, 48, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips Keane, S.; Calkins, S.D. Predicting Kindergarten Peer Social Status from Toddler and Preschool Problem Behavior. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2004, 32, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perhamus, G.R.; Ostrov, J.M. Inhibitory Control in Early Childhood Aggression Subtypes: Mediation by Irritability. Child. Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2021, 54, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, N.R.; Dodge, K.A. Social Information-Processing Mechanisms in Reactive and Proactive Aggression. Child Dev. 1996, 67, 993–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camodeca, M.; Goossens, F.A. Aggression, Social Cognitions, Anger and Sadness in Bullies and Victims. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2005, 46, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, K.A. Translational Science in Action: Hostile Attributional Style and the Development of Aggressive Behavior Problems. Dev. Psychopathol. 2006, 18, 791–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinstein, M.J.; Cillessen, A.H.N. Forms and Functions of Adolescent Peer Aggression Associated with High Levels of Peer Status. Merrill Palmer Q. 2003, 49, 310–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, K.A.; Coie, J.D. Social-Information-Processing Factors in Reactive and Proactive Aggression in Children’s Peer Groups. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 53, 1146–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tampke, E.C.; Fite, P.J.; Cooley, J.L. Bidirectional Associations between Affective Empathy and Proactive and Reactive Aggression. Aggress. Behav. 2020, 46, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useche, A.C.; Sullivan, A.L.; Merk, W.; Orobio de Castro, B. Relationships of Aggression Subtypes and Peer Status among Aggressive Boys in General Education and Emotional/Behavioral Disorder (EBD) Classrooms. Exceptionality 2014, 22, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walcott, C.M.; Upton, A.; Bolen, L.M.; Brown, M.B. Associations between Peer-Perceived Status and Aggression in Young Adolescents. Psychol. Sch. 2008, 45, 550–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, K.A.; Lochman, J.E.; Harnish, J.D.; Bates, J.E.; Pettit, G.S. Reactive and Proactive Aggression in School Children and Psychiatrically Impaired Chronically Assaultive Youth. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1997, 106, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, E.R.; Jensen, C.J.; Tisak, M.S. A Closer Examination of Aggressive Subtypes in Early Childhood: Contributions of Executive Function and Single-Parent Status. Early Child. Dev. Care 2019, 189, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endedijk, H.M.; Cillessen, A.H.N. Computerized Sociometric Assessment for Preschool Children. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2015, 39, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.A.; Watson, D. Constructing Validity: Basic Issues in Objective Scale Development; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Coie, J.D.; Dodge, K.A.; Coppotelli, H. Dimensions and Types of Social Status: A Cross-Age Perspective. Dev. Psychol. 1982, 18, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.-L.; Rosenthal, R.; Rubin, D.B. Quantitative Methods in Psychology Comparing Correlated Correlation Coefficients. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 111, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diedenhofen, B.; Musch, J. Cocor: A Comprehensive Solution for the Statistical Comparison of Correlations. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebanc, A.M. The Friendship Features of Preschool Children: Links with Prosocial Behavior and Aggression. Soc. Dev. 2003, 12, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrov, J.M.; Kamper, K.E.; Hart, E.J.; Godleski, S.A.; Blakely-Mcclure, S.J. A Gender-Balanced Approach to the Study of Peer Victimization and Aggression Subtypes in Early Childhood. Dev. Psychopathol. 2014, 26, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, R.M. The Role of Peer Preference and Friendship in the Development of Bullying and Peer Victimization in Children. Ph.D. Thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Murray-Close, D.; Ostrov, J.M. A Longitudinal Study of Forms and Functions of Aggressive Behavior in Early Childhood. Child Dev. 2009, 80, 828–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrov, J.M.; Keating, C.F. Gender Differences in Preschool Aggression During Free Play and Structured Interactions: An Observational Study. Soc. Dev. 2004, 13, 255–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias Rodrigues, A.; Cruz-Ferreira, A.; Marmeleira, J.; Veiga, G. Effects of Body-Oriented Interventions on Preschoolers’ Social-Emotional Competence: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 752930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias Rodrigues, A.; Marmeleira, J.; Pomar, C.; Lamy, E.; Guerreiro, D.; Veiga, G.; Rosário, P.; Gil-Madrona, P.; Saraiva, L.; Rodrigues, D.A.; et al. Body-Oriented Interventions to Promote Preschoolers’ Social-Emotional Competence: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1198199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veiga, G.; Guerreiro, D.; Marmeleira, J.; Santos, G.D.; Pomar, C. OUT to IN: A Body-Oriented Intervention Program to Promote Preschoolers’ Self-Regulation and Relationship Skills in the Outdoors. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1195305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prino, L.E.; Longobardi, C.; Fabris, M.A.; Settanni, M. Attachment Behaviors toward Teachers and Social Preference in Preschool Children. Early Educ. Dev. 2023, 34, 806–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longobardi, C.; Settanni, M.; Lin, S.; Fabris, M.A. Student–Teacher Relationship Quality and Prosocial Behaviour: The Mediating Role of Academic Achievement and a Positive Attitude towards School. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 91, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sette, S.; Spinrad, T.L.; Baumgartner, E. Links Among Italian Preschoolers’ Socioemotional Competence, Teacher-Child Relationship Quality, and Peer Acceptance. Early Educ. Dev. 2013, 24, 851–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Endedijk, H.M.; Breeman, L.D.; van Lissa, C.J.; Hendrickx, M.M.H.G.; den Boer, L.; Mainhard, T. The Teacher’s Invisible Hand: A Meta-Analysis of the Relevance of Teacher–Student Relationship Quality for Peer Relationships and the Contribution of Student Behavior. Rev. Educ. Res. 2022, 92, 370–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer Whitby, P.J.; Ogilvie, C.; Mancil, G.R. A Framework for Teaching Social Skills to Students with Asperger Syndrome in the General Education Classroom. J. Dev. Dis. 2012, 18, 62. [Google Scholar]

| Range Total (Raw Scores) | Mean Total (SD) | Mean Boys (SD) | Mean Girls (SD) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min (% of Children) | Max (% of Children) | Raw | Z | Raw | Z | Raw | Z | |

| Peer Preference | 0.31 (1%) | 0.71 (1%) | 0.52 (0.09) | 0.07 (0.92) | 0.51 (0.09) | 0.04 (0.93) | 0.53 (0.09) | 0.11 (0.93) |

| Reactive Aggression | 0.00 (13%) | 3 (1%) | 1.28 (0.73) | 0.00 (0.72) | 1.47 (0.67) | 0.20 (0.63) | 1.07 (0.75) | −0.23 (0.75) |

| Proactive Aggression | 0.00 (54%) | 2.33 (2%) | 0.34 (0.50) | 0.00 (0.75) | 0.49 (0.59) | 0.19 (0.84) | 0.17 (0.30) | −0.22 (0.55) |

| Peer Preference | Reactive Aggression | |

|---|---|---|

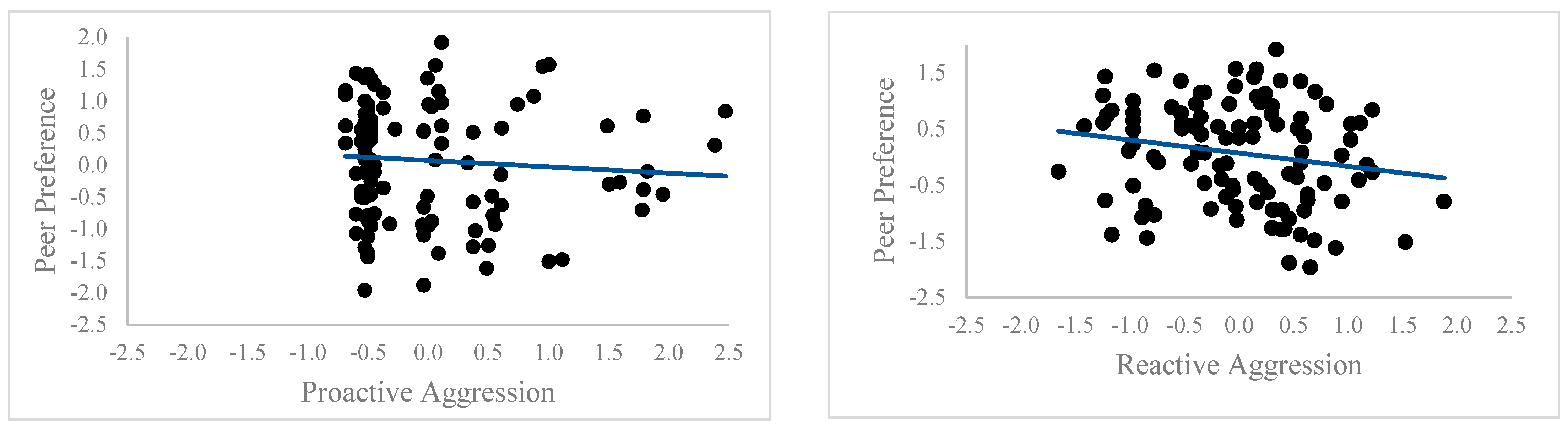

| Reactive Aggression | −0.18 * (−0.18 / −0.18) | - |

| Proactive Aggression | −0.08 (−0.13 / 0.02) | 0.40 *** (0.38 **/0.33 **) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

da Silva, B.M.S.; Veiga, G.; Rieffe, C.; Endedijk, H.M.; Güroğlu, B. Do My Reactions Outweigh My Actions? The Relation between Reactive and Proactive Aggression with Peer Acceptance in Preschoolers. Children 2023, 10, 1532. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091532

da Silva BMS, Veiga G, Rieffe C, Endedijk HM, Güroğlu B. Do My Reactions Outweigh My Actions? The Relation between Reactive and Proactive Aggression with Peer Acceptance in Preschoolers. Children. 2023; 10(9):1532. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091532

Chicago/Turabian Styleda Silva, Brenda M. S., Guida Veiga, Carolien Rieffe, Hinke M. Endedijk, and Berna Güroğlu. 2023. "Do My Reactions Outweigh My Actions? The Relation between Reactive and Proactive Aggression with Peer Acceptance in Preschoolers" Children 10, no. 9: 1532. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091532

APA Styleda Silva, B. M. S., Veiga, G., Rieffe, C., Endedijk, H. M., & Güroğlu, B. (2023). Do My Reactions Outweigh My Actions? The Relation between Reactive and Proactive Aggression with Peer Acceptance in Preschoolers. Children, 10(9), 1532. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091532