An Effective and Playful Way of Practicing Online Motor Proficiency in Preschool Children

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

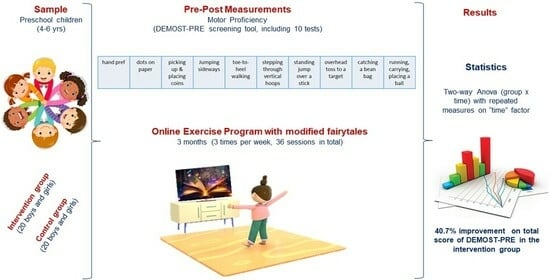

2.1. Participants

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Online Intervention Program with Modified Fairytales

2.4. Testing Procedures

- (a)

- An introductory test (not evaluated) of the procedure (“hand preference”);

- (b)

- Two tests of fine motor skills (“dots on paper/tapping” and “picking up and placing coins in an area”);

- (c)

- Four tests of gross motor dexterity (“jumping repeatedly sideways”, “toe-to-heel walking backwards”, “stepping through 3 vertical hoops”, and “standing jump over a stick”);

- (d)

- Two perceptual-motor tests (“overhead toss to a specific target” and “catching a bean bag”);

- (e)

- A test of combined gross, perceptual-motor, and fine dexterity (“running and carrying and placing a ball in a box”).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gallahue Dl Ozmun, J.C.; Goodway, J.D. Understanding Motor Development: Infants, Children, Adolescents and Adults, 7th ed.; McGraw Hill: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gallahue, D.L. Reaching Potentials: Transforming Early Childhood Curriculum and Assessment; National Association for the Education of Young Children: Washington, DC, USA, 1995; pp. 125–137. [Google Scholar]

- Willumsen, J.; Bull, F. Development of WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, and Sleep for Children Less Than 5 Years of Age. J. Phys. Act. Health 2020, 17, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.-P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruininks, R.H. Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency: Examiners Manual; American Guidance Service: Circle Pines, MN, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, D. Test of Gross Motor Development 2: Examiner’s Manual, 2nd ed.; PROED: Austin, TX, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger, L.A.; Bolger, L.E.; O’neill, C.; Coughlan, E.; Lacey, S.; O’brien, W.; Burns, C. Fundamental Movement Skill Proficiency and Health Among a Cohort of Irish Primary School Children. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport. 2019, 90, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, A.; Wainwright, N.; Williams, A. Interventions targeting motor skills in pre-school-aged children with direct or indirect parent engagement: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Int. J. Prim. Elem. Early Years Educ. 2023, 51, 1003–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deli, E.; Bakle, I.; Zachopoulou, E. Implementing intervention movement programs for kindergarten children. J. Early Child Res. 2006, 4, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derri, V.; Tsapakidou, A.; Zachopoulou, E.; Kioumourtzoglou, E. Effect of a Music and Movement Programme on Development of Locomotor Skills by Children 4 to 6 Years of Age. Eur. J. Phy. Educ. 2001, 6, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodway, J.D.; Branta, C.F. Influence of a motor skill intervention on fundamental motor skill development of disadvantaged preschool children. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport. 2003, 74, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodway, J.D.; Crowe, H.; Ward, P. Effects of Motor Skill Instruction on Fundamental Motor Skill Development. Adapt. Phys. Activ. Q. 2003, 20, 298–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livonen, S.; Sääkslahti, A.; Nissinen, K. The development of fundamental motor skills of four- to five-year-old preschool children and the effects of a preschool physical education curriculum. Early Child Dev. Care 2011, 181, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piek, J.; McLaren, S.; Kane, R.; Jensen, L.; Dender, A.; Roberts, C.; Rooney, R.; Packer, T.; Straker, L. Does the Animal Fun program improve motor performance in children aged 4–6 years? Hum. Mov. Sci. 2013, 32, 1086–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsapakidou, A.; Stefanidou, S.; Tsompanaki, E. Locomotor Development of Children Aged 3.5 to 5 Years in Nursery Schools in Greece. Rev. Eur. Stud. 2014, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venetsanou, F.; Kambas, A. How can a traditional Greek dances programme affect the motor proficiency of pre-school children? Res. Dance Educ. 2004, 5, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainwright, N.; Goodway, J.; John, A.; Thomas, K.; Piper, K.; Williams, K.; Gardener, D. Developing children’s motor skills in the Foundation Phase in Wales to support physical literacy. Int. Prim. Elem. Early Years Educ. 2019, 48, 566–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.H.-T. A study on gross motor skills of preschool children. J. Res. Child Educ. 2004, 19, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sport for Life. Facing COVID-19 Together. 2021. Available online: https://sportforlife.ca/facing-covid-19-together/ (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Curriculum for Preschool Education in Greece. 2021. Available online: https://ean.auth.gr/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/programma_spoudwn_2021.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2022). (In Greek language).

- Stevens-Smith, D. Movement and Learning: A valuable connection. Strategies 2004, 18, 10–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidoni, C.; Samalot-Rivera, A.; Takahiro, S. Physical Literacy in Early Childhood: Exploring Possibilities and Increasing Opportunities. Early Years Bull. 2015, 3, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Zrnzevic, N.; Static, M. Word and movement in the education of aesthetic and physical education. Res. Kin. 2015, 43, 157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Almond, L.; Whitehead, M. Physical Literacy: Clarifying the nature of the concept. Phys. Educ. Matters. 2012, 7, 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, M.; Cunningham, A.; Eyre, E. A combined movement and story-telling intervention enhances motor competence and language ability in pre-schoolers to a greater extent than movement or story-telling alone. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2019, 25, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyre, E.L.J.; Clark, C.C.T.; Tallis, J.; Hodson, D.; Lowton-Smith, S.; Nelson, C.; Noon, M.; Duncan, M.J. The Effects of Combined Movement and Storytelling Intervention on Motor Skills in South Asian and White Children Aged 5–6 Years Living in the United Kingdom. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, F.; Javad Mutab, M.; Zhooly, Z. Effectiveness of Movement and Storytelling Combination on Motor Skills and Anxiety of Children with 1 Developmental Coordination Disorder during Quarantine. Motor Behav. 2022, 14, 83–108. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Vitoria, R.; Faúndez-Casanova, C.; Cruz-Flores, A.; Hernandez-Martinez, J.; Jarpa-Preisler, S.; Villar-Cavieres, N.; González-Muzzio, M.T.; Garrido-González, L.; Flández-Valderrama, J.; Valdés-Badilla, P. Effects of Combined Movement and Storytelling Intervention on Fundamental Motor Skills, Language Development and Physical Activity Level in Children Aged 3 to 6 Years: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Children 2023, 10, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, C.; Cao, S.; Li, H. Young children’s online learning during COVID-19 pandemic: Chinese parents’ beliefs and attitudes. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 118, 105440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J. Learning and Teaching Online During COVID-19: Experiences of Student Teachers in an Early Childhood Education Practicum. Int. J. Early Child. 2020, 52, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SHAPE America. Shape of the Nation. Status of Physical Education in the USA. 2016. Available online: https://www.shapeamerica.org/uploads/pdfs/son/Shape-of-the-Nation-2016_web.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2022).

- Guan, H.; Okely, A.D.; Aguilar-Farias, N.; Del Pozo Cruz, B.; Draper, C.E.; El Hamdouchi, A.; Florindo, A.A.; Jáuregui, A.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Kontsevaya, A.; et al. Promoting healthy movement behaviours among children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 416–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM). ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, 9th ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 40–107. [Google Scholar]

- Kambas, A.; Venetsanou, F. Construct and Concurrent Validity of the Democritos Movement Screening Tool for Preschoolers. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2016, 28, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kambas, A.; Venetsanou, F. The Democritos Movement Screening Tool for Preschool Children (DEMOST-PRE©): Development and factorial validity. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2014, 35, 1528–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, K.; Leeger-Aschmann, C.S.; Monn, N.D.; Radtke, T.; Ott, L.V.; Rebholz, C.E.; Cruz, S.; Gerber, N.; Schmutz, E.A.; Puder, J.J.; et al. Interventions to Promote Fundamental Movement Skills in Childcare and Kindergarten: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 2045–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, T.; Kitayuguchi, J.; Fukushima, N.; Kamada, M.; Okada, S.; Ueta, K.; Tanaka, C.; Mutoh, Y. Fundamental movement skills in pre-schoolers before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan: A serial cross-sectional study. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2022, 27, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.; Sugiura, H.; Ito, Y.; Noritake, K.; Ochi, N. Effect of the COVID-19 emergency on physical function among school-aged children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pombo, A.; Luz, C.; de Sá, C.; Rodrigues, L.P.; Cordovil, R. Effects of the COVID-19 Lockdown on Portuguese Children’s Motor Competence. Children 2021, 8, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollatou, E.; Karadimou, K.; Gerodimos, V. Gender differences in musical aptitude, rhythmic ability and motor performance in preschool children. Early Child Dev. Care 2005, 175, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachopoulou, E.; Makri, A. A developmental perspective of divergent movement ability in early young children. Early Dev. Care 2005, 175, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallahue, D.L.; Ozmun, L.C. Understanding Motor Development: Infant, Children, Adolescents, Adults; W.C. Brown and Benchmark: Dubuque, IA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics | IG (n = 20) | CG (n = 20) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years old) | 5.10 ± 0.20 | 5.16 ± 0.28 |

| Body mass (kg) | 22.81 ± 4.16 | 21.87 ± 4.16 |

| Body height (m) | 1.15 ± 0.05 | 1.14 ± 0.03 |

| BMI (kg/m2) * | 16.93 ± 2.36 | 16.59 ± 2.48 |

| Objectives: 1. Motor skills (object control, locomotor, and stabilization skills), 2. physical fitness (flexibility, coordination abilities, speed, strength, and aerobic capacity), 3. cognitive domain (body parts and animals), and 4. emotional domain (perceived ability). Total duration: ~30 min (6 min story narration and 24 min exercise activities). Training contents: 7 exercise activities. Training equipment: 10 small toys, 2 large bags, 4 books, 3 water bottles, paper tape. | |

| Story | Transition–Exercise activities |

| Once upon a time, a little girl lived with her parents in the forest. Her father was a lumberjack and all day he worked in the forest cutting wood, making bundles, and selling them. | Transition: At this point, let us help her dad to gather more wood. Exercise activity 1: We invite the children to move the 10 bundles (“small toys”) from one side to the other (the children place the “small toys” in two large bags). The activity is repeated 3 times (with 40 s rest between repetitions). |

| One day the grandmother, who loved the little girl very much, gave her a red coat with a red hood. Can you imagine what the name of the little girl is? … So the “Little Red Riding Hood” had a great time at home. Every day she went out in her yard and started playing with her toys. | Transition: Let us play with her. Exercise activity 2: We invite the children to run quickly and freely in the area we have demarcated (3 m × 6 m). Each time we mention a body part, the children must stop and touch with their hand the mentioned body part (arm, leg, knee, back, elbow). The activity is repeated 5 times (5 times × 10 s running, with 5 s pause between repetitions to touch the called body part). |

| Suddenly, one day while she was playing, her mom called her and told her: “Grandma is very sick, you have to give her food to make her stronger. Be careful on the road and do not leave the path because you will get lost. Don’t forget to stay away from the Wolf!!” Little Red Riding Hood starts off happily on her big walk in the forest. | Transition: As she walked in the forest, she noticed that there were many obstacles in the path. She had to cross them to continue her way and not get lost. Exercise activity 3: We design, in the room, one track with “obstacles” and the children are called to cross them (jump with both feet forward two “books” in a row, balance on a route of 3 m paper tape, and zig-zag between 3 bottles). The activity is repeated 3 times with 30 s rest between the repetitions. |

| After she managed to cross the obstacles, she continued happily, BUT suddenly she met the WOLF in front of her. | Transition: Trying to hide from him… Exercise activity 4: The children move by crawling to the point we have set (3 m distance with paper tape). The activity is repeated twice with 40 s rest. |

| In the end, she managed to cross its path. After she continued on her way, she finally reached her grandmother’s house. However, the wolf tricked her, scared her, and suddenly appeared in front of her. - Where are you going? the wolf asked her. - I am going to give my grandmother some food because she is sick, Little Red Riding Hood answered him. - And where does your grandmother live? The wolf asked. - It’s not your business dear wolf… Little Red Riding Hood answered. | Transition: And then Little Red Riding Hood started running–running–running until she managed to get away from the wolf. Exercise activity 5: Children begin to run freely in the space we have demarcated (3 m × 6 m) by lowering their center of gravity and taking quick and gentle steps (duration 3 min). |

| However, the wolf did not give up. He was hungry, VERY hungry. He knew that there was only one house at the end of the path, so he thought that Little Red Riding Hood would probably go there. So, he decided to hide behind a tree and wait to see. In the meantime, Little Red Riding Hood came out of her hiding place and continued her way until she reached outside her grandmother’s house. | Transition: Little Red Riding Hood, instead of going inside, decided to play with the animals she met around the house. Exercise activity 6: The children start imitating the walk of the animals that we mentioned that Little Red Riding Hood met (elephant, frog, eagle) in the space (3 m × 6 m) we have demarcated (duration 5 min). |

| So, the wolf took the opportunity and entered the grandmother’s house first. TOK TOK TOK, he knocked on the door. - Who is there? Grandma asked - I am Little Red Riding Hood, answered the wolf, changing his voice. Please open for me to enter. I bring you fresh food. - Oh, come in, my little girl, said the grandmother. Suddenly when the grandmother opened the door, the wolf ate her and then he lay down comfortably on the bed waiting for Little Red Riding Hood to arrive… Little Red Riding Hood, after finishing her game with the animals in the yard, entered her grandmother’s house and she went to give her the food basket. Then the wolf got up and he ate Little Red Riding Hood as well. Later in the evening, a hunter was passing, he saw the door of the grandmother’s house open, and he was surprised. He entered the house and he saw the wolf sleeping. He looked more carefully and saw that something was moving in his tummy. Therefore, he decided to open the wolf’s tummy. SUDDENLY, the grandmother and Little Red Riding Hood came out. - WOW! How scared am I, said Little Red Riding Hood and gave her grandmother a big hug. | Transition: For so long in the wolf’s belly, we were caught. Let us stretch with Little Red Riding Hood and her grandmother. Exercise activity 7: We stretch our arms high and try to reach the sky and we fold our body trying to reach our toes, inhaling through the nose exhale through the mouth (3 sets × 8 reps, 30 s rest between sets). |

| Testing Variables | Group | Pre-Training | Post-Training |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Scores | Raw Scores | ||

| Dots on paper/tapping (number of dots) | IG | 31.40 ± 13.04 | 42.45 ± 14.09 |

| CG | 29.55 ± 12.67 | 31.30 ± 12.81 | |

| Picking up and placing coins in an area (time in s) | IG | 50.20 ± 10.50 | 46.5. ± 12.50 |

| CG | 50.10 ± 11.40 | 49.60 ± 11.50 | |

| Jumping repeatedly sideways (number of succesful jumps) | IG | 3.10 ± 2.19 | 5.10 ± 2.30 |

| CG | 2.74 ± 2.40 | 2.63 ± 2.48 | |

| Toe-to-heel walking backwards (number of succesful steps) | IG | 5.38 ± 5.08 | 10.57 ± 5.24 |

| CG | 4.32 ± 4.87 | 5.68 ± 5.61 | |

| Stepping through three vertical hoops (number of succesful trials) | IG | 0.71 ± 0.78 | 0.95 ± 0.66 |

| CG | 0.74 ± 0.61 | 0.73 ± 0.58 | |

| Standing jump over a stick (number of succesful jumps) | IG | 2.33 ± 1.57 | 2.76 ± 1.20 |

| CG | 2.58 ± 1.40 | 2.47 ± 1.28 | |

| Overhead toss to a specific target (number of succesful tosses) | IG | 3.19 ± 2.29 | 4.76 ± 2.59 |

| CG | 3.00 ± 2.45 | 2.95 ± 1.96 | |

| Catching a bean bag (number of succesful catches) | IG | 1.14 ± 1.24 | 1.38 ± 1.20 |

| CG | 1.12 ± 1.09 | 1.14 ± 1.19 | |

| Running and carrying and placing a ball in a box (time in s) | IG | 16.39 ± 3.65 | 13.86 ± 1.72 |

| CG | 15.99 ± 2.21 | 15.22 ± 2.00 | |

| Transformation | |||

| Testing Variables | Group | Pre-Training | Post-Training |

| Point Scores | Point Scores | ||

| Dots on paper/tapping | IG | 1.19 ± 1.69 | 2.76 ± 3.14 |

| CG | 0.84 ± 1.57 | 1.26 ± 2.08 | |

| Picking up and placing coins in an area | IG | 2.00 ± 0.5 | 3.00 ± 0.40 |

| CG | 2.00 ± 0.6 | 2.10 ± 0.5 | |

| Jumping repeatedly sideways | IG | 3.10 ± 2.19 | 5.10 ± 2.30 |

| CG | 2.74 ± 2.40 | 2.63 ± 2.48 | |

| Toe-to-heel walking backwards | IG | 5.38 ± 5.08 | 10.57 ± 5.24 |

| CG | 4.32 ± 4.87 | 5.68 ± 5.61 | |

| Stepping through three vertical hoops | IG | 0.71 ± 0.78 | 0.95 ± 0.66 |

| CG | 0.74 ± 0.61 | 0.73 ± 0.58 | |

| Standing jump over a stick | IG | 2.33 ± 1.57 | 2.76 ± 1.20 |

| CG | 2.58 ± 1.40 | 2.47 ± 1.28 | |

| Overhead toss to a specific target | IG | 3.19 ± 2.29 | 4.76 ± 2.59 |

| CG | 3.00 ± 2.45 | 2.95 ± 1.96 | |

| Catching a bean bag | IG | 1.14 ± 1.24 | 1.38 ± 1.20 |

| CG | 1.12 ± 1.09 | 1.14 ± 1.19 | |

| Running and carrying and placing a ball in a box | IG | 1.24 ± 1.22 | 2.43 ± 1.25 |

| CG | 1.68 ± 1.16 | 1.88 ± 1.41 | |

| DEMOST-PRE total score | IG | 20.28 ± 8.89 | 34.21 ± 9.5 |

| CG | 19.20± 10 | 20.84 ± 9.58 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adamopoulou, E.; Karatrantou, K.; Kaloudis, I.; Krommidas, C.; Gerodimos, V. An Effective and Playful Way of Practicing Online Motor Proficiency in Preschool Children. Children 2024, 11, 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11010130

Adamopoulou E, Karatrantou K, Kaloudis I, Krommidas C, Gerodimos V. An Effective and Playful Way of Practicing Online Motor Proficiency in Preschool Children. Children. 2024; 11(1):130. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11010130

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdamopoulou, Eleanna, Konstantina Karatrantou, Ioannis Kaloudis, Charalampos Krommidas, and Vassilis Gerodimos. 2024. "An Effective and Playful Way of Practicing Online Motor Proficiency in Preschool Children" Children 11, no. 1: 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11010130

APA StyleAdamopoulou, E., Karatrantou, K., Kaloudis, I., Krommidas, C., & Gerodimos, V. (2024). An Effective and Playful Way of Practicing Online Motor Proficiency in Preschool Children. Children, 11(1), 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11010130