Play Nicely: Evaluation of a Brief Intervention to Reduce Physical Punishment and the Beliefs That Justify It

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Physical Punishment

1.2. Parents’ Beliefs about Physical Punishment

1.3. Hypothesis

2. Materials and Methods

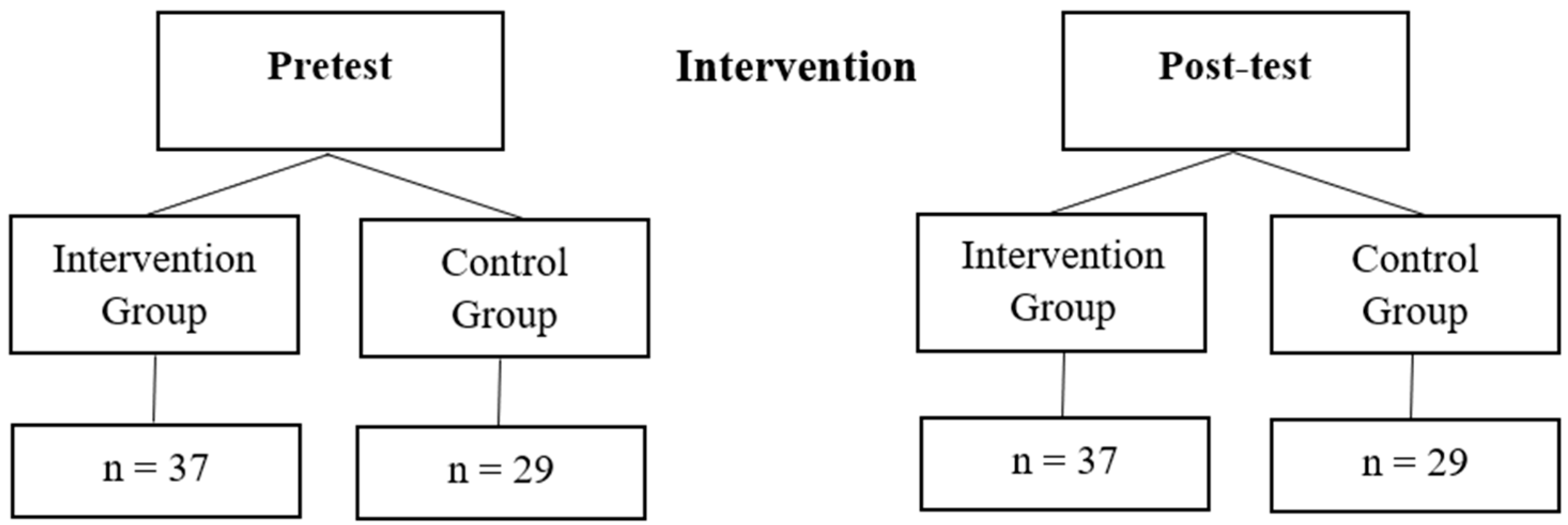

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measurements

2.3.1. Scale of Beliefs about the Positive Effects of Physical Punishment on Children [75]

2.3.2. Physical Assault Scale of the Spanish Version of the Parent–Child Conflict Tactics Scale (CTSPC) [76]

2.4. Procedure

- -

- Classified by the program as very good options, i.e., redirect behavior, redirect with a question, ask how the other child feels, and establish rules.

- -

- Classified by the program as a good option if other strategies have failed: Ask your child how they feel.

- -

- Classified by the program as not recommended because there are better alternatives: Spanking the child, ignoring the behavior, and speaking angrily.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Control Group and Intervention Group

3.2. Relationship between Beliefs Justifying Physical Punishment and Its Utilization

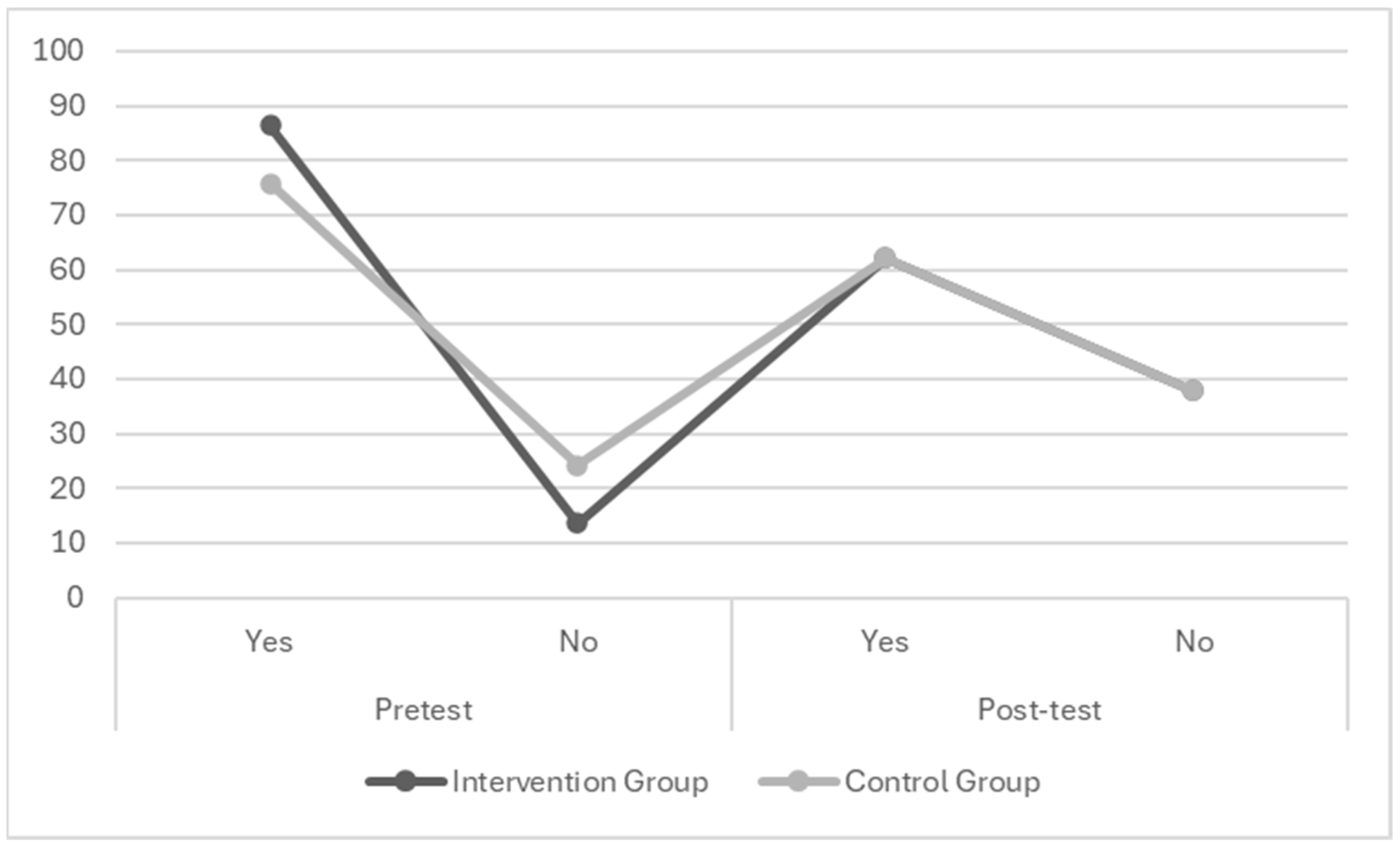

3.3. Assessment of Change in the Use of Physical Punishment

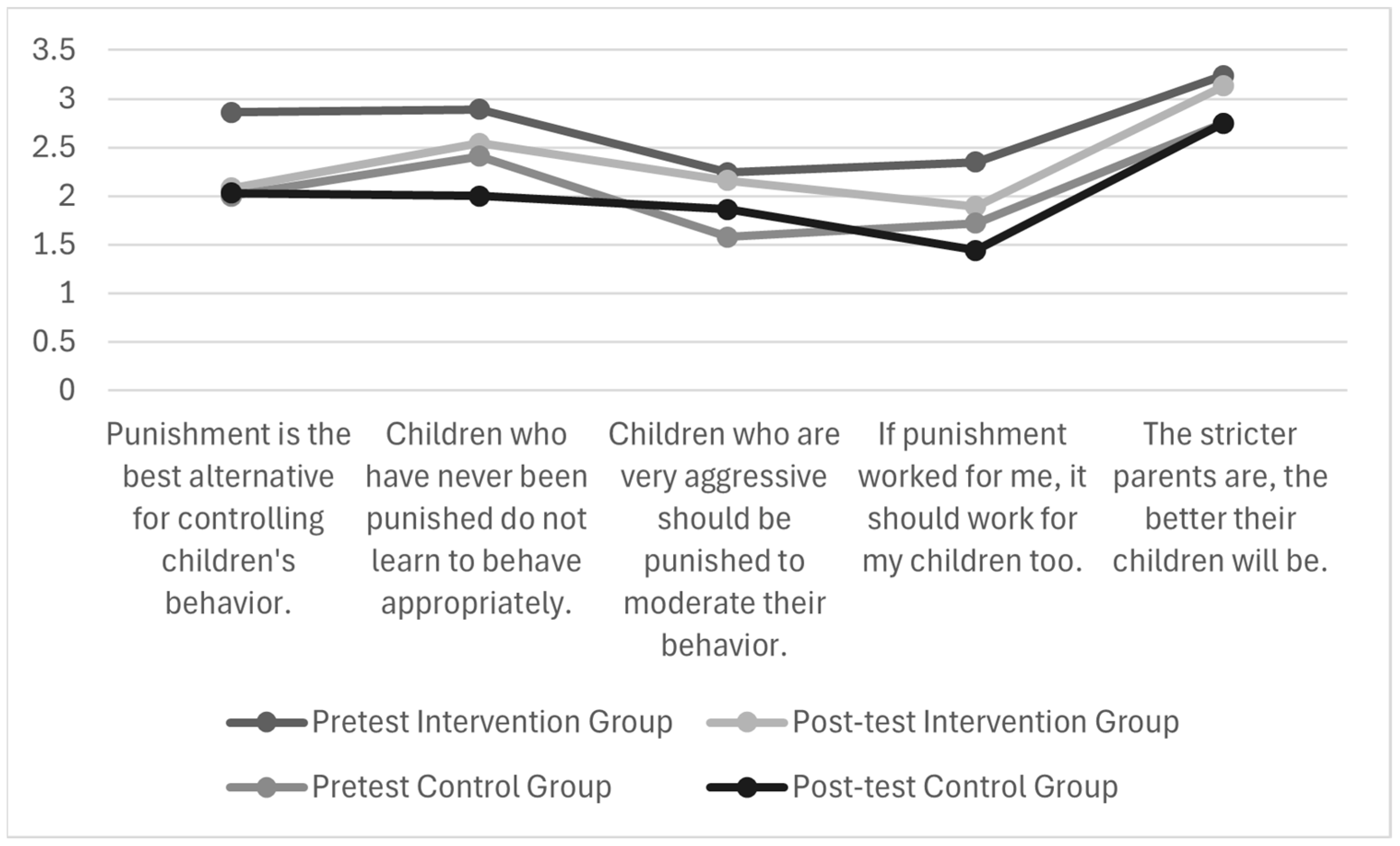

3.4. Assessment of Change in Beliefs about the Positive Effects of Physical Punishment

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implications of the Research

4.2. Limitations of the Study and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Freeman, M. Upholding the Dignity and Best Interests of Children: International Law and the Corporal Punishment of Children. In The Human Rights of Children; Brill Nijhoff: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2022; Volume 105, pp. 93–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershoff, E.T.; Bitensky, S.H. The case against corporal punishment of children: Converging evidence from social science research and international human rights law and implications for U.S. public policy. Psychol. Public Policy Law 2007, 13, 231–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations General Assembly. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- Fondo de las Naciones Unidas para la Infancia [UNICEF]. Convención Sobre los Derechos del Niño; UNICEF Comité Español: Madrid, Spain, 2006; Available online: https://www.un.org/es/events/childrenday/pdf/derechos.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- Economic Commission for Latin American and Caribbean—ECLAC. La Agenda 2030 y los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible: Una Oportunidad para América Latina y el Caribe. Objetivos, Metas e Indicadores Mundiales; CEPAL: Santiago, Chile, 2019; pp. 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Illachura, V.C.; Montesinos-Malpartida, M.I.; Bellido-Boza, L.; Puyén, Z.M.; Blitchtein-Winicki, D. Physical punishment and effective verbal communication in children aged 9–36 months, according to sex: Secondary analysis of a national survey. BMC Pediatr. 2024, 24, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuartas, J.; Grogan-Kaylor, A.; Ma, J.; Castillo, B. Civil Conflict, Domestic Violence, and Poverty as Predictors of Corporal Punishment in Colombia. Child Abus. Negl. 2019, 90, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization [WHO]. Informe Sobre la Situación Mundial de la Prevención de la Violencia Contra los Niños 2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-92-4-000715-4. [Google Scholar]

- Fondo de las Naciones Unidas para la Infancia [UNICEF]. Disciplina Violenta en América Latina y el Caribe: Un Análisis Estadístico; UNICEF: Panama City, Panama, 2018; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/lac/media/1726/file/UNICEF%20Disciplina%20Violenta.pdf (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- Cuartas, J. Physical punishment against the early childhood in Colombia: National and regional prevalence, sociodemographic gaps, and ten-year trends. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 93, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo, A.; González, M.R.; Fonseca, L.; Segura, S. Prevalence, Severity and Chronicity of Corporal Punishment in Colombian Families. Child Abus. Rev. 2020, 29, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congreso de Colombia. Ley 2089 de 2021. Por Medio de la Cual se Prohíbe el Uso del Castigo Físico, los Tratos Crueles, Humillantes o Degradantes y Cualquier Tipo de Violencia Como Método de Corrección Contra Niñas, Niños y Adolescentes y se Dictan Otras Disposiciones. D.O. No. 51674. Available online: https://www.suin-juriscol.gov.co/viewDocument.asp?id=30041715 (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- Gobierno de Colombia. Estrategia Nacional Pedagógica y de Prevención del Castigo Físico, los Tratos Crueles, Humillantes o Degradantes 2022/2030, 2nd ed.; Gobierno de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2022; ISBN 978-958-53100-1-8. [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff, E.T. Corporal Punishment by Parents and Associated Child Behaviors and Experiences: A Meta-Analytic and Theoretical Review. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 539–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, J.L.; Behl, L.E. Relationships among Parental Beliefs in Corporal Punishment, Reported Stress, and Physical Child Abuse Potential. Child Abus. Negl. 2001, 25, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lansford, J.E.; Woodlief, D.; Malone, P.S.; Oburu, P.; Pastorelli, C.; Skinner, A.T.; Sorbring, E.; Tapanya, S.; Tirado, L.M.U.; Zelli, A.; et al. A Longitudinal Examination of Mothers’ and Fathers’ Social Information Processing Biases and Harsh Discipline in Nine Countries. Dev. Psychopathol. 2014, 26, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansford, J.E.; Godwin, J.; Uribe Tirado, L.M.; Zelli, A.; Al-Hassan, S.M.; Bacchini, D.; Bombi, A.S.; Bornstein, M.H.; Chang, L.; Deater-Deckard, K.; et al. Individual, Family, and Culture Level Contributions to Child Physical Abuse and Neglect: A Longitudinal Study in Nine Countries. Dev. Psychopathol. 2015, 27, 1417–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansford, J.E.; Godwin, J.; Bornstein, M.H.; Chang, L.; Deater-Deckard, K.; Di Giunta, L.; Dodge, K.A.; Malone, P.S.; Oburu, P.; Pastorelli, C.; et al. Reward Sensitivity, Impulse Control, and Social Cognition as Mediators of the Link Between Childhood Family Adversity and Externalizing Behavior in Eight Countries. Dev. Psychopathol. 2017, 29, 1675–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ember, C.R.; Ember, M. War, Socialization, and Interpersonal Violence. J. Confl. Resolut. 1994, 38, 620–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewkes, R.; Sikweyiya, Y.; Jama-Shai, N. The Challenges of Research on Violence in Post-Conflict Bougainville. Lancet 2014, 383, 2039–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lansford, J.E.; Dodge, K.A. Cultural Norms for Adult Corporal Punishment of Children and Societal Rates of Endorsement and Use of Violence. Parenting 2008, 8, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straus, M.A. Prevalence, societal causes and trends in corporal punishment by parents in world perspective. Law Contemp. Probl. 2010, 73, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Straus, M.A.; Stewart, J.H. Corporal punishment by American parents: National data on prevalence, chronicity, severity, and duration, in relation to child and family characteristics. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 1999, 2, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuartas, J. Corporal Punishment and Child Development in Low- and- Middle-Income Countries: Progress, Challenges, and Directions. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2023, 54, 1607–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alampay, L.P.; Godwin, J.; Lansford, J.E.; Bombi, A.S.; Bornstein, M.H.; Chang, L.; Deater-Deckard, K.; Giunta, L.D.; Dodge, K.A.; Malone, P.S.; et al. Severity and justness do not moderate the relation between corporal punishment and negative child outcomes. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2017, 41, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, C.J. Spanking, corporal punishment and negative long-term outcomes: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 33, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gershoff, E.T. More harm than good: A summary of scientific research on the intended and unintended effects of corporal punishment on children. Law Contemp. Probl. 2010, 73, 31–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff, E.T.; Grogan-Kaylor, A. Spanking and Child Outcomes: Old Controversies and New Meta-Analyses. J. Fam. Psychol. 2016, 30, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grogan-Kaylor, A.; Castillo, B.; Pace, G.T.; Ward, K.P.; Ma, J.; Lee, S.J.; Knauer, H. Global Perspectives on Physical and Nonphysical Discipline: A Bayesian Multilevel Analysis. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2021, 45, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, P.; Wong, R.S.; Li, S.L.; Chan, K.L.; Ho, F.K.; Chow, C.-b. Mental Health Consequences of Childhood Physical Abuse in Chinese Populations. Trauma Violence Abus. 2016, 17, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoury-Kassabri, M.; Attar-Schwartz, S.; Zur, H. Understanding the mediating role of corporal punishment in the association between maternal stress, efficacy, co-parenting and children’s adjustment difficulties among Arab mothers. Child Abus. Negl. 2014, 38, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulvaney, M.K.; Mebert, C.J. Parental corporal punishment predicts behavior problems in early childhood. J. Fam. Psychol. 2007, 21, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straus, M.A.; Paschall, M.J. Corporal Punishment by Mothers and Development of Children’s Cognitive Ability: A Longitudinal Study of Two Nationally Representative Age Cohorts. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2009, 18, 459–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomoda, A.; Suzuki, H.; Rabi, K.; Sheu, Y.-S.; Polcari, A.; Teicher, M.H. Reduced prefrontal cortical gray matter volume in young adults exposed to harsh corporal punishment. NeuroImage 2009, 47, T66–T71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piché, G.; Huỳnh, C.; Clément, M.-È.; Durrant, J.E. Predicting externalizing and prosocial behaviors in children from parental use of corporal punishment. Infant Child Dev. 2016, 26, e2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrant, J.; Ensom, R. Physical punishment of children: Lessons from 20 years of research. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2012, 184, 1373–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, K.M.Y.; Lim, E.; Cheung, H.S.; Choo, C.; Fu, C.S.L. The impact and perceived effectiveness of physical punishment: A qualitative study of young adults’ retrospective accounts. OSF 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershoff, E.T. Spanking and Child Development: We Know Enough Now to Stop Hitting Our Children. Child Dev. Perspect. 2013, 7, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Y.; Fredman, S.J.; Feinberg, M.E. Parenting Stress Mediates the Association Between Negative Affectivity and Harsh Parenting: A Longitudinal Dyadic Analysis. J. Fam. Psychol. 2017, 31, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornstein, M.H.; Putnick, D.L.; Suwalsky, J.T.D. Parenting Cognitions → Parenting Practices → Child Adjustment? The Standard Model. Dev. Psychopathol. 2018, 30, 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuartas, J.; Gershoff, E.T.; Bailey, D.; McCoy, D.C. Physical punishment and child, adolescent, and adult outcomes in low- and middle-income countries: Protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2022, 11, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, M.R.; Trujillo, A. Examining the Moderating Role of Parental Stress in the Relationship between Parental Beliefs on Corporal Punishment and Its Utilization as a Behavior Correction Strategy among Colombian Parents. Children 2024, 11, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lansford, J.E.; Cappa, C.; Putnick, D.L.; Bornstein, M.H.; Deater-Deckard, K.; Bradley, R.H. Change Over Time in Parents’ Beliefs About and Reported Use of Corporal Punishment in Eight Countries with and Without Legal Bans. Child Abus. Negl. 2017, 71, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakunmoju, S.B. The Effects of Perception and Childhood History on the Likelihood of Using Corporal Punishment on Children in Southwest Nigeria. J. Educ. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2024, 37, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittrup, B. Attitudes Predict the Use of Physical Punishment: A Prospective Study of the Emergence of Disciplinary Practices. Pediatrics 2006, 117, 2055–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sungwa, R.; Jackson, L.; Kahembe, J. Findings on the Use of Corporal Punishment. In Corporal Punishment in Preschool and at Home in Tanzania; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard, K.; Lansford, J.E.; Dodge, K.A.; Pettit, G.S.; Bates, J.E. The development of attitudes about physical punishment: An 8-year longitudinal study. J. Fam. Psychol. 2003, 17, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horn, I.B.; Cheng, T.L.; Joseph, J. Discipline in the African American Community: The Impact of Socioeconomic Status on Beliefs and Practices. Pediatrics 2004, 113, 1236–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchinal, M.; Skinner, D.; Reznick, J.S. European American and African American Mothers’ Beliefs About Parenting and Disciplining Infants: A Mixed-Method Analysis. Parenting 2010, 10, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clément, M.-È.; Dufour, S.; Gagné, M.-H.; Gilbert, S. Prediction of health, education, and psychosocial professionals’ attitudes in favor of parental use of corporal punishment. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 109, 104766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ispa, J.M.; Halgunseth, L.C. Talking about corporal punishment: Nine low-income African American mothers’ perspectives. Early Child. Res. Q. 2004, 19, 463–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Liu, L.; Wang, M. Intergenerational Transmission of Harsh Discipline: The Moderating Role of Parenting Stress and Parent Gender. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 79, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wang, M.; Xing, X. Attitudes mediate the intergenerational transmission of corporal punishment in China. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 76, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrera, M.; Chaux, E.; Trujillo, D. ¿Los Mejores Perfumes Vienen en Envases Pequeños?: Potencial de las Intervenciones Breves en el Contexto Educativo. Rev. Colomb. Psicol. 2015, 24, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, D.K.; Cohen, G.L.; Nelson, L.D.; Nussbaum, A.D.; Bunyan, D.P.; Garcia, J. Affirmed yet unaware: Exploring the role of awareness in the process of self-affirmation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 97, 745–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anagnostaki, L.; Kollia, I.; Layiou-Lignos, E. Implementation of a brief early intervention in times of socio-economic crisis: Effects on parental stress. J. Child Psychother. 2019, 45, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.; Sanders, M.R.; Turner KM, T.; Morawska, A. A randomized controlled trial evaluating a low-intensity interactive online parenting intervention, Triple P Online Brief, with parents of children with early onset conduct problems. Behav. Res. Ther. 2017, 91, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, S.J.; Jadaa, D.-A.; Brody, J.; Landy, S.; Tallett, S.E.; Watson, W.; Shea, B.; Stephens, D. Brief psychoeducational parenting program: An evaluation and 1-year follow-up. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2003, 42, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesterfield, J.A.; Porzig-Drummond, R.; Stevenson, R.J.; Stevenson, C.S. Evaluating a brief behavioral parenting program for parents of school-aged children with ADHD. Parenting 2021, 21, 216–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joachim, S.; Sanders, M.R.; Turner, K.M.T. Reducing preschoolers’ disruptive behavior in public with a brief parent discussion group. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2009, 41, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morawska, A.; Haslam, D.; Milne, D.; Sanders, M.R. Evaluation of a brief parenting discussion group for parents of young children. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2011, 32, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitillas, C.; Berástegui, A.; Halty, A.; Rodríguez, P.; Kamara, M.; Mesman, J. Enhancing maternal sensitivity in contexts of urban extreme poverty in Sierra Leone: A pilot study. Infant Ment. Health J. 2021, 42, 812–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rait, S. The Holding Hands Project: Effectiveness in promoting positive parent–child interactions. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 2012, 28, 353–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner KM, T.; Sanders, M.R. Help when it’s needed first: A controlled evaluation of brief, preventive behavioral family intervention in a primary care setting. Behav. Ther. 2006, 37, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholer, S. Play Nicely. In Ending the Physical Punishment of Children: A Guide for Clinicians and Practitioners; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhart, K.; Knox, M.; Hunter, K.; Pennewitt, D.; Schrouder, K. Decreasing Caregivers’ Positive Attitudes Toward Spanking. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2018, 32, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholer, S.J.; Goad, S. Feedback on a Multimedia Violence Prevention Program. Clin. Pediatr. 2003, 42, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.E.; Hudnut-Beumler, J.; Scholer, S.J. Can Discipline Education be Culturally Sensitive? Matern. Child Health J. 2016, 21, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavis, A.; Hudnut-Beumler, J.; Webb, M.W.; Neely, J.A.; Bickman, L.; Dietrich, M.S.; Scholer, S.J. A brief intervention affects parents’ attitudes toward using less physical punishment. Child Abus. Negl. 2013, 37, 1192–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholer, S.J.; Hamilton, E.C.; Johnson, M.C.; Scott, T.A. A Brief Intervention May Affect Parents’ Attitudes Toward Using Less Physical Punishment. Fam. Community Health 2010, 33, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudnut-Beumler, J.; Smith, A.; Scholer, S.J. How to Convince Parents to Stop Spanking Their Children. Clin. Pediatr. 2018, 57, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholer, S.J.; Hudnut-Beumler, J.; Dietrich, M.S. A Brief Primary Care Intervention Helps Parents Develop Plans to Discipline. Pediatrics 2010, 125, e242–e249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholer, S.J.; Martin, H.K.; Adams, L.; Dietrich, M.S. A Brief Intervention in Primary Care to Improve Parents’ Discipline Practices and Reach Other Caregivers. Clin. Pediatr. 2024, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, R.; Fernández, C.; Baptista, M.D.P. Concepción o elección del diseño de investigación. In Metodología de la Investigación, 6th ed.; Hernández, R., Fernández, C., Baptista, M.D.P., Eds.; McGraw-Hill: Mexico City, Mexico, 2014; pp. 126–168. ISBN 978-1-4562-2396-0. [Google Scholar]

- Corral-Verdugo, V.; Frías-Armenta, M.; Romero, M.; Muñoz, A. Validity of a Scale Measuring Beliefs Regarding the “Positive” Effects of Punishing Children: A Study of Mexican Mothers. Child Abus. Negl. 1995, 19, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straus, M.A.; Hamby, S.L.; Finkelhor, D.; Moore, D.W.; Runyan, D. Identification of Child Maltreatment with the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development and Psychometric Data for a National Sample of American Parents. Child Abus. Negl. 1998, 22, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association [WMA]. WMA Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Available online: https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/ (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- Hernández-Molina, S.L. El estrés Parental como Moderador Entre el Castigo Físico y el Comportamiento Agresivo: Aportes para el Desarrollo de Programas de Intervención. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de La Sabana, Chía, Colombia, 2020. Available online: https://intellectum.unisabana.edu.co/handle/10818/43441 (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- Narayan, A.J.; Lieberman, A.F.; Masten, A.S. Intergenerational transmission and prevention of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 85, 101997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Overall Sample | Intervention Group | Control Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | F | % | F | % | F | % | |

| Parents | Mothers | 51 | 77.27 | 29 | 78.37 | 22 | 75.86 |

| Fathers | 15 | 22.72 | 8 | 21.6 | 7 | 24.13 | |

| Marital status | Married | 45 | 68.18 | 23 | 62.16 | 22 | 75.86 |

| Cohabiting/Unmarried partnership | 14 | 21.21 | 9 | 24.32 | 5 | 17.24 | |

| Single | 6 | 9.09 | 4 | 10.81 | 2 | 6.89 | |

| Separated or Divorced | 1 | 1.51 | 1 | 2.70 | 0 | 0 | |

| Socio-economic level | High | 13 | 19.69 | 6 | 16.21 | 7 | 24.13 |

| Middle | 51 | 77.27 | 29 | 78.37 | 22 | 75.86 | |

| Low | 2 | 3.03 | 2 | 5.40 | 0 | ||

| Education | High School | 5 | 7.57 | 4 | 10.81 | 1 | 3.44 |

| Technical | 2 | 3.03 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6.89 | |

| Professional | 22 | 33.33 | 11 | 29.73 | 11 | 37.93 | |

| Postgraduate | 37 | 56.06 | 22 | 59.45 | 15 | 51.72 | |

| Number of children | 1 child | 28 | 42.42 | 13 | 35.13 | 15 | 51.72 |

| 2 children | 30 | 45.45 | 18 | 48.64 | 12 | 41.37 | |

| 3 children | 6 | 9.09 | 4 | 10.81 | 2 | 6.89 | |

| 5 children | 1 | 1.51 | 1 | 2.70 | 0 | ||

| 8 children | 1 | 1.51 | 1 | 2.70 | 0 | ||

| Beliefs | Mean | Standard Deviation | Independent Sample t-Test (IG—CG) | Value p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Punishment is the best alternative for controlling children’s behavior | 2.485 | 2.143 | 1.649 | 0.104 |

| Children who have never been punished do not learn to behave appropriately | 2.682 | 2.531 | 0.759 | 0.451 |

| Children who are very aggressive should be punished to moderate their behavior | 1.955 | 1.965 | 1.357 | 0.179 |

| If punishment worked for me, it should work for my children too | 2.076 | 2.093 | 1.213 | 0.230 |

| The stricter parents are, the better their children will be | 3.030 | 2.294 | 0.850 | 0.398 |

| Beliefs | Type of Physical Punishment | Pearson’s r |

|---|---|---|

| Punishment is the best alternative for controlling children’s behavior. | 2. I spanked him/her on the bottom with something like a belt, brush, stick, or another hard object. | 0.412 *** |

| 3. I slapped his/her hand, arm, or leg. | 0.291 * | |

| 6. I pulled his/her hair (hair pulling). | 0.263 * | |

| Children who have never been punished do not learn to behave appropriately. | 1. I spanked him/her on the bottom with my hand. | 0.352 ** |

| 2. I spanked him/her on the bottom with something like a belt, brush, stick, or another hard object. | 0.322 ** | |

| 3. I slapped his/her hand, arm, or leg. | 0.245 * | |

| Children who are very aggressive should be punished to moderate their behavior. | 1. I spanked him/her on the bottom with my hand. | 0.415 *** |

| 2. I spanked him/her on the bottom with something like a belt, brush, stick, or another hard object. | 0.314 * | |

| 3. I slapped his/her hand, arm, or leg. | 0.258 * | |

| 6. I pulled his/her hair (hair pulling). | 0.321 ** | |

| If punishment worked for me, it should work for my children too. | 1. I spanked him/her on the bottom with my hand. | 0.410 *** |

| 2. I spanked him/her on the bottom with something like a belt, brush, stick, or another hard object. | 0.275 * | |

| 3. I slapped his/her hand, arm, or leg. | 0.312 * | |

| The stricter parents are, the better their children will be. | 1. I spanked him/her on the bottom with my hand. | 0.525 *** |

| 3. I slapped his/her hand, arm, or leg. | 0.285 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nuñez-Talero, D.V.; González, M.R.; Trujillo, A. Play Nicely: Evaluation of a Brief Intervention to Reduce Physical Punishment and the Beliefs That Justify It. Children 2024, 11, 608. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11050608

Nuñez-Talero DV, González MR, Trujillo A. Play Nicely: Evaluation of a Brief Intervention to Reduce Physical Punishment and the Beliefs That Justify It. Children. 2024; 11(5):608. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11050608

Chicago/Turabian StyleNuñez-Talero, Danna Valentina, Martha Rocío González, and Angela Trujillo. 2024. "Play Nicely: Evaluation of a Brief Intervention to Reduce Physical Punishment and the Beliefs That Justify It" Children 11, no. 5: 608. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11050608

APA StyleNuñez-Talero, D. V., González, M. R., & Trujillo, A. (2024). Play Nicely: Evaluation of a Brief Intervention to Reduce Physical Punishment and the Beliefs That Justify It. Children, 11(5), 608. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11050608