Maternal Reports of Preterm and Sick Term Infants’ Settling, Sleeping and Feeding in the 9 Months after Discharge from Neonatal Nursery: An Observational Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Maternal perceptions of crying, settling and sleep patterns across the first 9 months after discharge.

- The degree of maternal bother with infant sleep, settling and crying duration and night waking frequency across the first 9 months after discharge.

- Maternal breastfeeding self-efficacy.

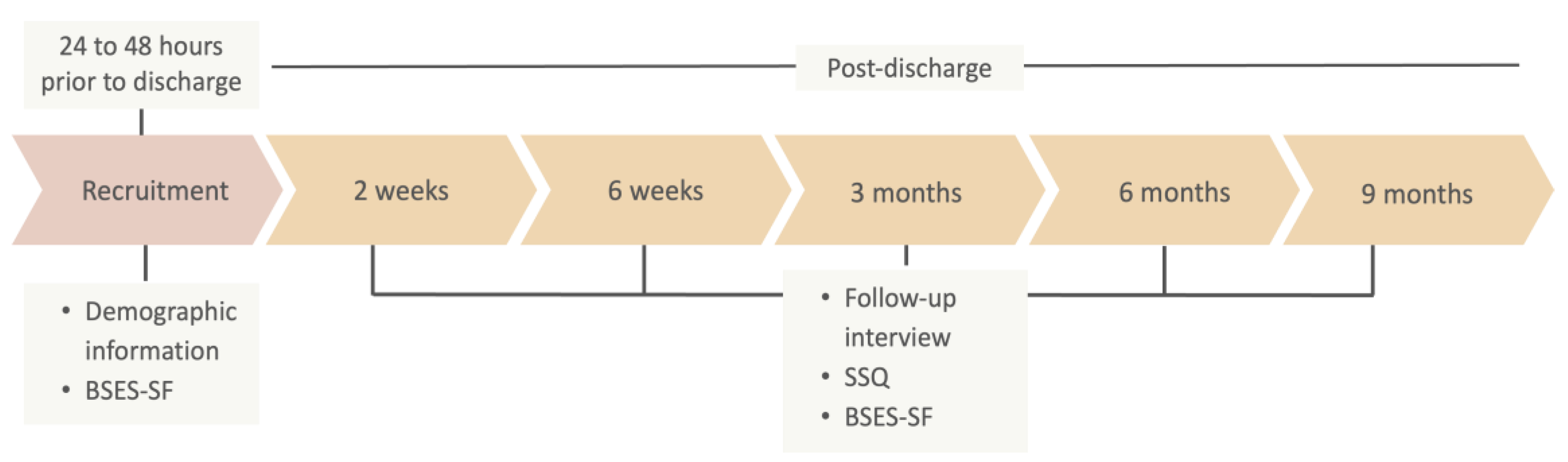

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Sample Size

2.3. Participants and Recruitment

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Instruments

2.5.1. Demographic and Infant Health Information

2.5.2. Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale-Short Form (BSES-SF)

2.5.3. Follow-Up Interview

2.5.4. Sleep and Settle Questionnaire (SSQ)

3. Data Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Biologically “Normal”

5.2. Maternal Bother with Sick/Preterm Infant Sleep

5.2.1. Maternal Bother in Sick/Preterm vs. Healthy Term Cohorts

5.2.2. Maternal Bother in Preterm vs. Term Sick Infants

5.3. Breastfeeding Confidence in Mothers of Sick/Preterm Infants

5.4. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| SSQ Items (M ± SD) N = 101 | 2 Weeks (n = 97) | 6 Weeks (n = 96) | 3 Months (n = 93) | 6 Months (n = 93) | 9 Months (n = 85) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <33 Weeks (n = 37) | 33–36.9 Weeks (n = 25) | Term Sick (n = 35) | <33 Weeks (n = 37) | 33–36.9 Weeks (n = 24) | Term Sick (n = 35) | <33 Weeks (n = 35) | 33–36.9 Weeks (n = 22) | Term Sick (n = 36) | <33 Weeks (n = 35) | 33–36.9 Weeks (n = 22) | Term Sick (n = 36) | <33 Weeks (n = 31) | 33–36.9 Weeks (n = 21) | Term Sick (n = 33) | |

| Sleep duration (h) | |||||||||||||||

| Morning sleep | 2.7 ± 1.1 | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 2.7 ± 1.2 | 2.4 ± 0.9 | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 2.5 ± 1.4 | 2.1 ± 1.2 | 2.1 ± 1.0 | 1.5 ± 0.9 | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.6 |

| Afternoon sleep | 2.6 ± 1.3 | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 2.5 ± 0.9 | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 2.2 ± 1.1 | 1.9 ± 0.9 | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 1.8 ± 1.1 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 1.7 ± 0.7 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 1.1 ± 0.6 | 1.6 ± 0.8 |

| Evening sleep | 2.3 ± 0.9 | 2.2 ± 1.0 | 2.1 ± 1.1 | 2.3 ± 0.9 | 2.1 ± 0.8 | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 1.5 ± 1.0 | 1.7 ± 1.0 | 2.4 ± 1.0 | 2.2 ± 1.1 | 2.1 ± 1.0 | 2.4 ± 1.0 | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 2.6 ± 0.9 |

| Night sleep | 2.9 ± 1.2 | 2.8 ± 1.0 | 3.5 ± 1.1 | 3.8 ± 1.5 | 3.7 ± 1.3 | 5.0 ± 1.2 | 5.5 ± 1.8 | 5.4 ± 1.5 | 5.8 ± 1.4 | 6.3 ± 1.4 | 5.5 ± 1.5 | 5.9 ± 1.5 | 6.5 ± 1.1 | 6.5 ± 1.1 | 6.7 ± 0.9 |

| Daytime sleep frequency | 4.0 ± 1.1 | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 3.6 ± 1.0 | 3.3 ± 1.2 | 3.5 ± 0.8 | 3.1 ± 0.9 | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 3.1 ± 0.7 | 2.9 ± 0.9 | 2.5 ± 0.9 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 2.3 ± 0.7 | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.5 |

| Night-waking frequency | 2.8 ± 1.6 | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 1.9 ± 1.1 | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 1.3 ± 1.5 | 1.3 ± 1.4 | 1.0 ± 0.9 | 0.6 ± 0.8 | 1.5 ± 1.6 | 1.5 ± 1.6 | 0.5 ± 0.7 | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 0.7 ± 1.4 |

| Settling duration (min) | |||||||||||||||

| Daytime | 38.1 ± 68.1 | 13.0 ± 11.1 | 17.9 ± 14.2 | 24.4 ± 22.9 | 17.9 ± 13.3 | 26.3 ± 35.5 | 19.0 ± 18.8 | 14.3 ± 12.6 | 13.7 ± 12.5 | 14.8 ± 12.2 | 11.0 ± 6.4 | 12.0 ± 13.8 | 11.7 ± 11.1 | 9.0 ± 6.4 | 11.0 ± 12.0 |

| Evening | 39.2 ± 66.0 | 21.6 ± 21.2 | 26.4 ± 40.9 | 28.3 ± 24.9 | 27.0 ± 29.1 | 27.2 ± 34.9 | 34.1 ± 40.9 | 25.5 ± 31.5 | 18.3 ± 20.5 | 13.6 ± 12.8 | 10.2 ± 6.3 | 11.3 ± 12.3 | 13.4 ± 13.0 | 13.2 ± 14.6 | 12.5 ± 17.1 |

| Night | 47.7 ± 70.3 | 22.4 ± 22.4 | 14.4 ± 14.3 | 24.1 ± 25.4 | 22.8 ± 31.6 | 13.9 ± 16.4 | 23.7 ± 27.4 | 18.1 ± 32.9 | 8.1 ± 6.2 | 8.5 ± 9.6 | 7.7 ± 8.8 | 8.1 ± 11.5 | 13.8 ± 17.5 | 9.5 ± 14.0 | 9.2 ± 18.9 |

| Crying duration (min) | |||||||||||||||

| Daytime | 31.9 ± 39.7 | 34.5 ± 46.3 | 49.0 ± 80.6 | 48.1 ± 43.5 | 62.7 ± 86.1 | 57.5 ± 75.0 | 43.7 ± 34.3 | 65.7 ± 98.5 | 42.6 ± 41.1 | 49.1 ± 41.2 | 48.4 ± 41.7 | 37.4 ± 42.5 | 40.6 ± 36.6 | 43.6 ± 40.9 | 41.7 ± 60.8 |

| Evening | 18.9 ± 20.9 | 31.4 ± 38.8 | 25.5 ± 34.1 | 33.0 ± 45.2 | 55.6 ± 77.1 | 27.3 ± 40.3 | 32.1 ± 32.1 | 49.5 ± 49.6 | 21.3 ± 20.8 | 23.6 ± 27.0 | 20.2 ± 17.2 | 13.9 ± 13.7 | 14.9 ± 17.1 | 17.9 ± 17.7 | 14.1 ± 21.7 |

| Night | 25.9 ± 27.8 | 31.2 ± 37.9 | 18.1 ± 20.6 | 22.9 ± 31.4 | 48.7 ± 91.4 | 7.4 ± 8.5 | 10.5 ± 12.6 | 36.9 ± 75.4 | 4.6 ± 4.5 | 7.4 ± 21.7 | 3.6 ± 7.1 | 5.3 ± 8.8 | 3.6 ± 7.9 | 12.7 ± 23.4 | 7.6 ± 21.6 |

| Total bother score | 17.7 ± 6.3 | 16.1 ± 5.3 | 15.9 ± 6.2 | 16.5 ± 5.9 | 17.6 ± 8.9 | 14.7 ± 5.1 | 14.8 ± 5.6 | 15.9 ± 5.3 | 13.1 ± 4.1 | 13.8 ± 6.1 | 15.3 ± 4.8 | 14.3 ± 5.1 | 14.5 ± 6.5 | 16.1 ± 5.5 | 14.9 ± 6.1 |

| Total confidence score | 9.1 ± 1.2 | 9.1 ± 0.9 | 8.9 ± 0.9 | 9.2 ± 0.8 | 9.1 ± 1.1 | 9.1 ± 0.9 | 9.4 ± 0.7 | 9.0 ± 0.8 | 9.4 ± 0.9 | 9.6 ± 0.8 | 9.2 ± 1.0 | 9.6 ± 0.7 | 9.5 ± 0.7 | 9.0 ± 1.0 | 9.5 ± 0.8 |

| Total confidence in partner score | 4.1 ± 1.0 | 3.8 ± 1.1 | 3.7 ± 0.9 | 4.0 ± 1.2 | 3.5 ± 0.9 | 3.6 ± 1.0 | 3.7 ± 1.2 | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 3.8 ± 1.1 | 3.7 ± 1.2 | 3.7 ± 1.0 | 3.7 ± 1.1 | 4.0 ± 1.2 | 3.9 ± 0.8 | 3.7 ± 1.0 |

References

- Paavonen, E.J.; Saarenpaa-Heikkila, O.; Morales-Munoz, I.; Virta, M.; Hakala, N.; Polkki, P.; Kylliainen, A.; Karlsson, H.; Paunio, T.; Karlsson, L. Normal sleep development in infants: Findings from two large birth cohorts. Sleep Med. 2020, 69, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwichtenberg, A.J.; Shah, P.E.; Poehlmann, J. Sleep and attachment in preterm infants. Infant Ment. Health J. 2013, 34, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudzik, A.E.F.; Ball, H.L. Biologically normal sleep in the mother-infant dyad. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2021, 33, e23589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayer, J.K.; Hiscock, H.; Hampton, A.; Wake, M. Sleep problems in young infants and maternal mental and physical health. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2007, 43, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pecora, G.; Focaroli, V.; Paoletti, M.; Barca, L.; Chiarotti, F.; Borghi, A.M.; Gasparini, C.; Caravale, B.; Bombaci, I.; Gastaldi, S.; et al. Infant sleep and development: Concurrent and longitudinal relations during the first 8 months of life. Infant Behav. Dev. 2022, 67, 101719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tham, E.K.; Schneider, N.; Broekman, B.F. Infant sleep and its relation with cognition and growth: A narrative review. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2017, 9, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, E.S. What is “normal” infant sleep? Why we still do not know. Psychol. Rep. 2021, 124, 651–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galland, B.C.; Taylor, B.J.; Elder, D.E.; Herbison, P. Normal sleep patterns in infants and children: A systematic review of observational studies. Sleep Med. Rev. 2012, 16, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.M.; France, K.G.; Blampied, N.M. The consolidation of infants’ nocturnal sleep across the first year of life. Sleep Med. Rev. 2011, 15, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchitel, J.; Vanhatalo, S.; Austin, T. Early development of sleep and brain functional connectivity in term-born and preterm infants. Pediatr. Res. 2022, 91, 771–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.S.; Paiva, T.; Hsu, J.F.; Kuo, M.C.; Guilleminault, C. Sleep and breathing in premature infants at 6 months post-natal age. BMC Pediatr. 2014, 14, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgoulas, A.; Jones, L.; Laudiano-Dray, M.P.; Meek, J.; Fabrizi, L.; Whitehead, K. Sleep-wake regulation in preterm and term infants. Sleep 2021, 44, zsaa148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trickett, J.; Hill, C.; Austin, T.; Johnson, S. The impact of preterm birth on sleep through infancy, childhood and adolescence and its implications. Children 2022, 9, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quante, M.; McGee, G.W.; Yu, X.T.; von Ash, T.; Luo, M.; Kaplan, E.R.; Rueschman, M.; Haneuse, S.; Davison, K.K.; Redline, S.; et al. Associations of sleep-related behaviors and the sleep environment at infant age one month with sleep patterns in infants five months later. Sleep Med. 2022, 94, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbally, M.; Lewis, A.J.; McEgan, K.; Scalzo, K.; Islam, F.A. Breastfeeding and infant sleep patterns: An australian population study. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2013, 49, E147–E152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudzik, A.E.F.; Ball, H.L. Exploring maternal perceptions of infant sleep and feeding method among mothers in the united kingdom: A qualitative focus group study. Matern. Child Health J. 2016, 20, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwaydi, M.A.; Lai, C.T.; Rea, A.; Gridneva, Z.; Perrella, S.L.; Wlodek, M.E.; Geddes, D.T. Circadian variation in human milk hormones and macronutrients. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, T. Infant sleep problems and interventions: A review. Infant Behav. Dev. 2017, 47, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loutzenhiser, L.; Ahlquist, A.; Hoffman, J. Infant and maternal factors associated with maternal perceptions of infant sleep problems. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2011, 29, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetti, N.; D’Souza, L.; Tchernegovski, P.; Blunden, S. Parents’ perceptions of the quality of infant sleep behaviours and practices: A qualitative systematic review. Infant Child Dev. 2023, 32, e2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulgen, O.; Baris, H.E.; Askan, O.O.; Akdere, S.K.; Ilgin, C.; Ozdemir, H.; Bekiroglu, N.; Gucuyener, K.; Ozek, E.; Boran, P. Sleep assessment in preterm infants: Use of actigraphy and aeeg. Sleep Med. 2023, 101, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolke, D.; Meyer, R.; Ohrt, B.; Riegel, K. The incidence of sleeping problems in preterm and fullterm infants discharged from neonatal special care units: An epidemiological longitudinal study. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1995, 36, 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirtbas-Isik, G.; Yardimci-Lokmanoglu, B.N.; Livanelioglu, A.; Mutlu, A. Sensory processing and sleep characteristics in preterm infants in the early period of life. Sleep Med. 2023, 106, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, K.A. Differential effects of breast- and formula-feeding on preterm infants’ sleep-wake patterns. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2000, 29, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holditch-Davis, D.; Scher, M.; Schwartz, T.; Hudson-Barr, D. Sleeping and waking state development in preterm infants. Early Hum. Dev. 2004, 80, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govindaswamy, P.; Laing, S.; Waters, D.; Walker, K.; Spence, K.; Badawi, N. Needs and stressors of parents of term and near-term infants in the nicu: A systematic review with best practice guidelines. Early Hum. Dev. 2019, 139, 104839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marthinsen, G.N.; Helseth, S.; Fegran, L. Sleep and its relationship to health in parents of preterm infants: A scoping review. BMC Pediatr. 2018, 18, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donovan, A.; Nixon, E. “Weathering the storm”: Mothers’ and fathers’ experiences of parenting a preterm infant. Infant Ment. Health J. 2019, 40, 573–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrella, S.L.; Williams, J.; Nathan, E.A.; Fenwick, J.; Hartmann, P.E.; Geddes, D.T. Influences on breastfeeding outcomes for healthy term and preterm/sick infants. Breastfeed. Med. 2012, 7, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrella, S.L.; Dix-Matthews, A.; Williams, J.; Rea, A.; Geddes, D.T. Breastfeeding and maternal perceptions of infant sleep, settle and cry patterns in the first 9 months. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas. 2016. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/mf/2033.0.55.001 (accessed on 3 July 2023).

- Dennis, C.L. The breastfeeding self-efficacy scale: Psychometric assessment of the short form. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2003, 32, 734–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthey, S. The sleep and settle questionnaire for parents of infants: Psychometric properties. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2001, 37, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiscock, H. The crying baby. Aust. Fam. Physician 2006, 35, 680. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lupini, F.; Leichman, E.S.; Lee, C.; Mindell, J.A. Sleep patterns, problems, and ecology in young children born preterm and full-term and their mothers. Sleep Med. 2021, 81, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, J.; Hiscock, H. Early infant crying and sleeping problems: A pilot study of impact on parental well-being and parent-endorsed strategies for management. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2007, 43, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiscock, H.; Cook, F.; Bayer, J.; Le, H.N.; Mensah, F.; Cann, W.; Symon, B.; St James-Roberts, I. Preventing early infant sleep and crying problems and postnatal depression: A randomized trial. Pediatrics 2014, 133, e346–e354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, W.A.; Lucas-Thompson, R.G.; Germo, G.R.; Keller, M.A.; Davis, E.P.; Sandman, C.A. Eye of the beholder? Maternal mental health and the quality of infant sleep. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 79, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, C.C.; Figueiredo, B. Unidirectional and bidirectional links between maternal depression symptoms and infant sleep problems. J. Sleep Res. 2021, 30, e13363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vertsberger, D.; Tikotzky, L.; Baruchi, O.; Knafo-Noam, A. Parents’ perceptions of infants’ nighttime sleep patterns predict mothers’ negativity: A longitudinal study. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2021, 42, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakewell-Sachs, S.; Gennaro, S. Parenting the post-nicu premature infant. MCN Am. J. Matern./Child. Nurs. 2004, 29, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, A.; Mayer, A.; Lohaus, A. Sleep-related parenting self-efficacy and parent-reported sleep in young children: A dyadic analysis of parental actor and partner effects. Sleep Health 2022, 8, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuthill, E.L.; McGrath, J.M.; Graber, M.; Cusson, R.M.; Young, S.L. Breastfeeding self-efficacy: A critical review of available instruments. J. Hum. Lact. 2016, 32, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyna, B.A.; Pickler, R.H.; Thompson, A. A descriptive study of mothers’ experiences feeding their preterm infants after discharge. Adv. Neonatal Care 2006, 6, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenblad, A.K.; Funkquist, E.-L. Self-efficacy in breastfeeding predicts how mothers perceive their preterm infant’s state-regulation. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2022, 17, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kair, L.R.; Flaherman, V.J.; Newby, K.A.; Colaizy, T.T. The experience of breastfeeding the late preterm infant: A qualitative study. Breastfeed. Med. 2015, 10, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Maternal Characteristics n (%) | <33 Weeks (n = 35) | 33–36.9 Weeks (n = 22) | Term Sick (n = 37) | Overall (N = 94) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| <30 years | 19 (54.3) | 9 (40.9) | 14 (37.8) | 42 (44.7) |

| ≥30 years | 16 (45.8) | 12 (54.5) | 23 (62.2) | 51 (54.3) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 1 (4.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Highest education level | ||||

| High school | 11 (31.4) | 7 (31.8) | 18 (48.6) | 36 (38.3) |

| TAFE 1/diploma | 15 (42.9) | 7 (31.8) | 6 (16.2) | 28 (29.8) |

| Tertiary | 9 (25.7) | 8 (36.4) | 13 (35.1) | 30 (31.9) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married/de facto | 34 (97.1) | 21 (95.5) | 36 (97.3) | 91 (96.8) |

| Ethnic group | ||||

| Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander | 1 (2.9) | 2 (9.1) | 2 (5.4) | 5 (5.3) |

| Caucasian | 28 (80.0) | 20 (90.9) | 31 (83.8) | 79 (84.0) |

| Asian | 2 (5.7) | 0 (0) | 3 (8.1) | 5 (5.3) |

| Other | 3 (8.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.2) |

| Missing | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.7) | 2 (2.1) |

| Breastfed previously | 12 (34.3) | 12 (54.5) | 19 (51.4) | 43 (45.7) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (1.1) |

| Intended breastfeeding duration | ||||

| 0–6 months | 4 (11.4) | 8 (36.4) | 6 (16.2) | 18 (19.1) |

| 6–12 months | 16 (45.7) | 8 (36.4) | 25 (67.6) | 49 (52.1) |

| >12 months | 6 (17.2) | 3 (13.6) | 4 (10.8) | 13 (13.9) |

| “As long as I can/I want” | 8 (22.9) | 2 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 10 (10.6) |

| Missing | 1 (2.9) | 1 (4.5) | 2 (5.4) | 4 (4.3) |

| Infant Characteristics n (%) | <33 Weeks (n = 37) | 33–36.9 Weeks (n = 26) | Term Sick (n = 38) | Overall (N = 101) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infant sex = female | 19 (51.4) | 14 (53.8) | 20 (60.5) | 56 (55.4) |

| Twin infants | 5 (13.5) | 10 (38.5) | 4 (10.5) | 19 (18.8) |

| Birth gestation (weeks) | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 28.4 (27.0, 30.9) | 35.0 (33.9, 35.0) | 39.3 (38.1, 40.0) | 35.0 (30.4, 68.6) |

| Age at discharge (days) | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 62.0 (37.0, 83.0) | 13.5 (9.75, 17.3) | 13.0 (8.0, 21.0) | 22.5 (11.0, 61.5) |

| Missing n (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (7.7) | 9 (23.7) | 11 (10.9) |

| Length of NICU admission (days) | ||||

| Median (Q1, Q3) | 64.0 (37.0, 83.0) | 15.0 (9.0, 18.0) | 9.0 (5.0, 13.8) | 21.0 (9.0, 62.5) |

| Missing n (%) | 0 (0) | 5 (19.2) | 8 (21.1) | 13 (12.9) |

| Feeding Outcomes N = 101 | Discharge | 2 Weeks | 6 Weeks | 3 Months | 6 Months | 9 Months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSES-SF score | n = 92 | n = 68 | n = 62 | n = 48 | n = 39 | n = 24 |

| M ± SD | 57.9 ± 9.3 | 59.1 ± 8.9 | 60.9 ± 8.1 | 62.9 ± 8.2 | 64.5 ± 6.4 | 64.4 ± 6.1 |

| Feeding method n (%) | n = 96 | n = 98 | n = 99 | n = 98 | n = 94 | |

| Fully breastfeeding | 66 (65.3) | 46 (45.5) | 35 (34.7) | 35 (34.7) | 24 (23.8) | |

| Mixed feeding | 21 (20.8) | 25 (24.8) | 26 (25.7) | 13 (12.9) | 9 (8.9) | |

| Formula feeding | 9 (8.9) | 27 (26.7) | 38 (37.6) | 50 (49.5) | 61 (60.4) |

| SSQ Items (M ± SD) N = 101 | 2 Weeks (n = 97) | 6 Weeks (n = 96) | 3 Months (n = 93) | 6 Months (n = 93) | 9 Months (n = 85) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep duration (h) | |||||

| Morning sleep | 2.5 ± 1.0 | 2.4 ± 1.0 | 2.2 ± 1.2 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 1.4 ± 0.6 |

| Afternoon sleep | 2.4 ± 1.1 | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 1.9 ± 1.0 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 1.4 ± 0.7 |

| Evening sleep | 2.2 ± 1.0 | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 1.9 ± 1.1 | 2.2 ± 1.0 | 2.5 ± 0.9 |

| Night sleep | 3.1 ± 1.2 | 4.2 ± 1.5 | 5.6 ± 1.6 | 5.9 ± 1.5 | 6.6 ± 1.0 |

| Daytime sleep frequency | 3.8 ± 1.0 | 3.3 ± 1.0 | 3.0 ± 0.8 | 2.5 ± 0.8 | 2.0 ± 0.4 |

| Night-waking frequency | 2.6 ± 1.2 | 1.8 ± 1.0 | 1.2 ± 1.2 | 1.2 ± 1.4 | 0.8 ± 1.1 |

| Settling duration (min) | |||||

| Daytime | 24.2 ± 44.0 | 23.5 ± 27.0 | 15.8 ± 15.2 | 12.8 ± 11.8 | 10.8 ± 10.5 |

| Evening | 30.0 ± 48.8 | 27.6 ± 29.5 | 25.6 ± 32.0 | 11.9 ± 11.3 | 13.0 ± 14.9 |

| Night | 29.0 ± 47.4 | 20.0 ± 24.2 | 16.3 ± 24.3 | 8.1 ± 10.2 | 10.9 ± 16.9 |

| Crying duration (min) | |||||

| Daytime | 38.7 ± 59.0 | 55.2 ± 67.4 | 48.5 ± 58.4 | 44.4 ± 41.8 | 41.8 ± 47.8 |

| Evening | 24.5 ± 31.3 | 36.6 ± 53.7 | 32.2 ± 35.1 | 19.0 ± 20.6 | 15.3 ± 19.0 |

| Night | 24.4 ± 28.8 | 24.0 ± 51.4 | 14.8 ± 39.5 | 5.7 ± 14.5 | 7.4 ± 18.5 |

| Total bother score (9–45) | 16.6 ± 6.0 | 16.1 ± 6.6 | 14.4 ± 5.1 | 14.3 ± 5.4 | 15.1 ± 6.1 |

| Total confidence score (2–10) | 9.0 ± 1.0 | 9.2 ± 0.9 | 9.3 ± 0.9 | 9.5 ± 0.8 | 9.4 ± 0.8 |

| Total confidence in partner score (1–5) | 3.9 ± 1.0 | 3.7 ± 1.0 | 3.8 ± 1.1 | 3.7 ± 1.1 | 3.8 ± 1.0 |

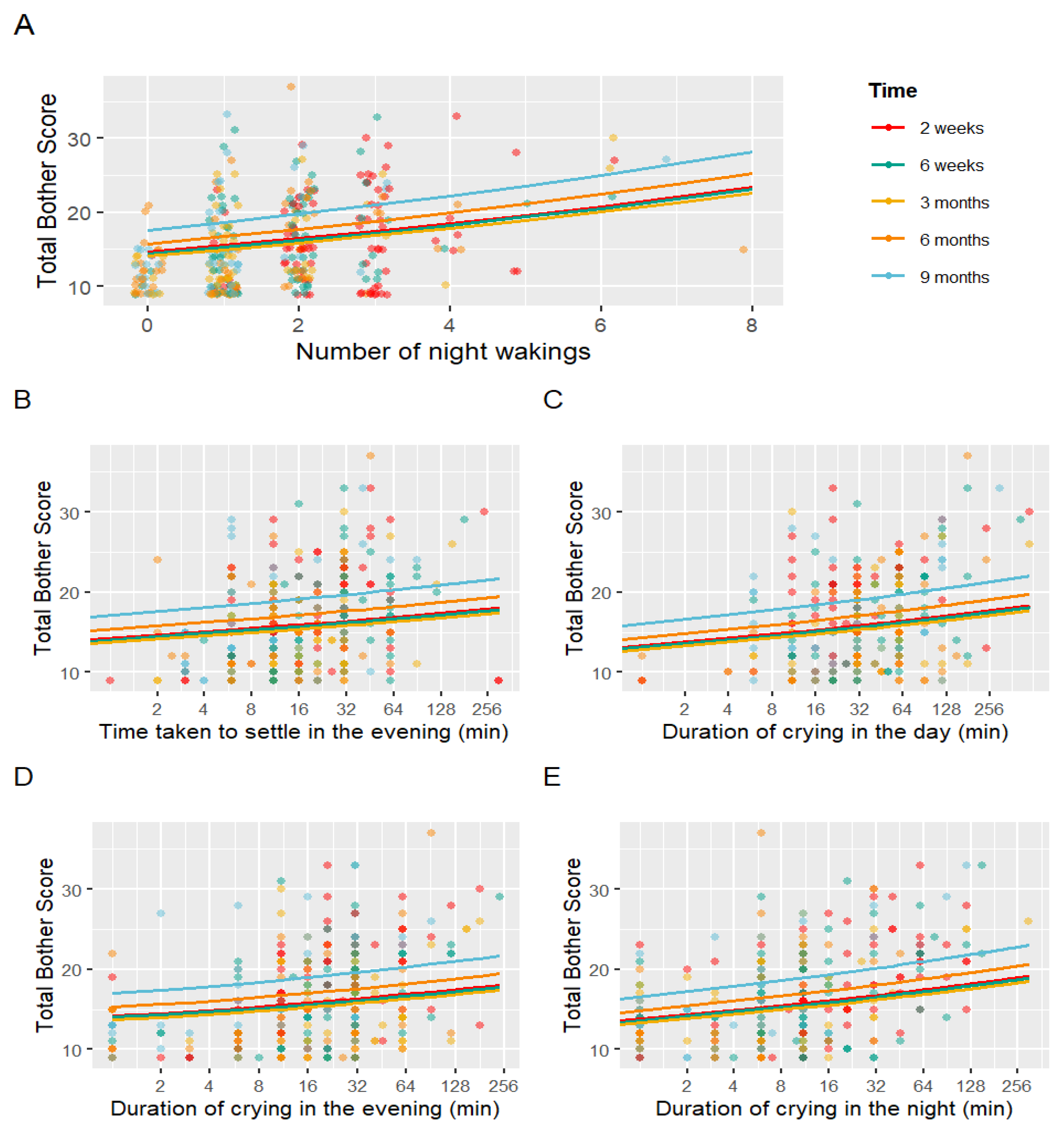

| Fixed Effects | Estimate | SE | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 20.501 | 0.182 | <0.001 |

| Time (6 weeks) | 0.987 | 0.034 | 0.701 |

| Time (3 months) | 0.965 | 0.040 | 0.376 |

| Time (6 months) | 1.077 | 0.041 | 0.071 |

| Time (9 months) | 1.202 | 0.044 | <0.001 |

| Night-waking frequency | 1.060 | 0.013 | <0.001 |

| Settling duration (evening) | 1.031 | 0.012 | 0.010 |

| Crying duration (day) | 1.038 | 0.012 | 0.001 |

| Crying duration (evening) | 1.035 | 0.010 | <0.001 |

| Crying duration (night) | 1.043 | 0.009 | <0.001 |

| Total confidence score | 0.915 | 0.018 | <0.001 |

| Total confidence in partner score | 0.947 | 0.015 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lim, E.S.M.; Williams, J.; Vlaskovsky, P.; Ireland, D.J.; Geddes, D.T.; Perrella, S.L. Maternal Reports of Preterm and Sick Term Infants’ Settling, Sleeping and Feeding in the 9 Months after Discharge from Neonatal Nursery: An Observational Study. Children 2024, 11, 655. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11060655

Lim ESM, Williams J, Vlaskovsky P, Ireland DJ, Geddes DT, Perrella SL. Maternal Reports of Preterm and Sick Term Infants’ Settling, Sleeping and Feeding in the 9 Months after Discharge from Neonatal Nursery: An Observational Study. Children. 2024; 11(6):655. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11060655

Chicago/Turabian StyleLim, Emma Shu Min, Julie Williams, Philip Vlaskovsky, Demelza J. Ireland, Donna T. Geddes, and Sharon L. Perrella. 2024. "Maternal Reports of Preterm and Sick Term Infants’ Settling, Sleeping and Feeding in the 9 Months after Discharge from Neonatal Nursery: An Observational Study" Children 11, no. 6: 655. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11060655