Unveiling Child Sexual Abuse Disclosure in China: An Ecological Exploration of Survivors’ Experiences

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Explore the barriers to disclosing child sexual abuse in China;

- Reveal how specific socio-cultural factors influence child disclosure in China;

- Highlight the similarities and differences between this influence and international mainstream research.

1.1. Defining ‘Disclosure’

1.2. Theoretical Framework

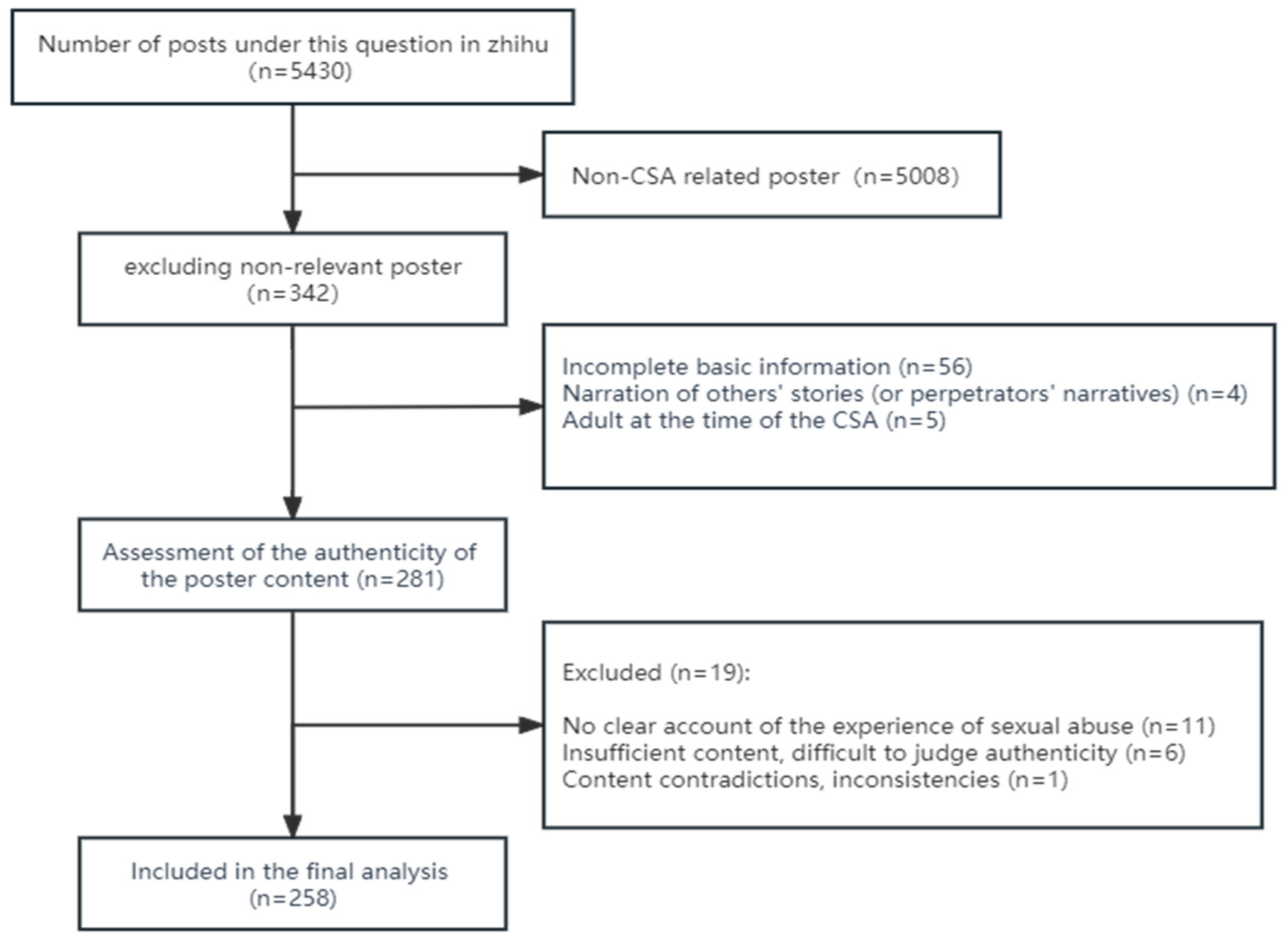

2. Methodology

2.1. Data Collection and Analysis

2.2. The Characteristics of Victims and Perpetrators of CSA

2.2.1. Information of Victims

2.2.2. Information of Perpetrators

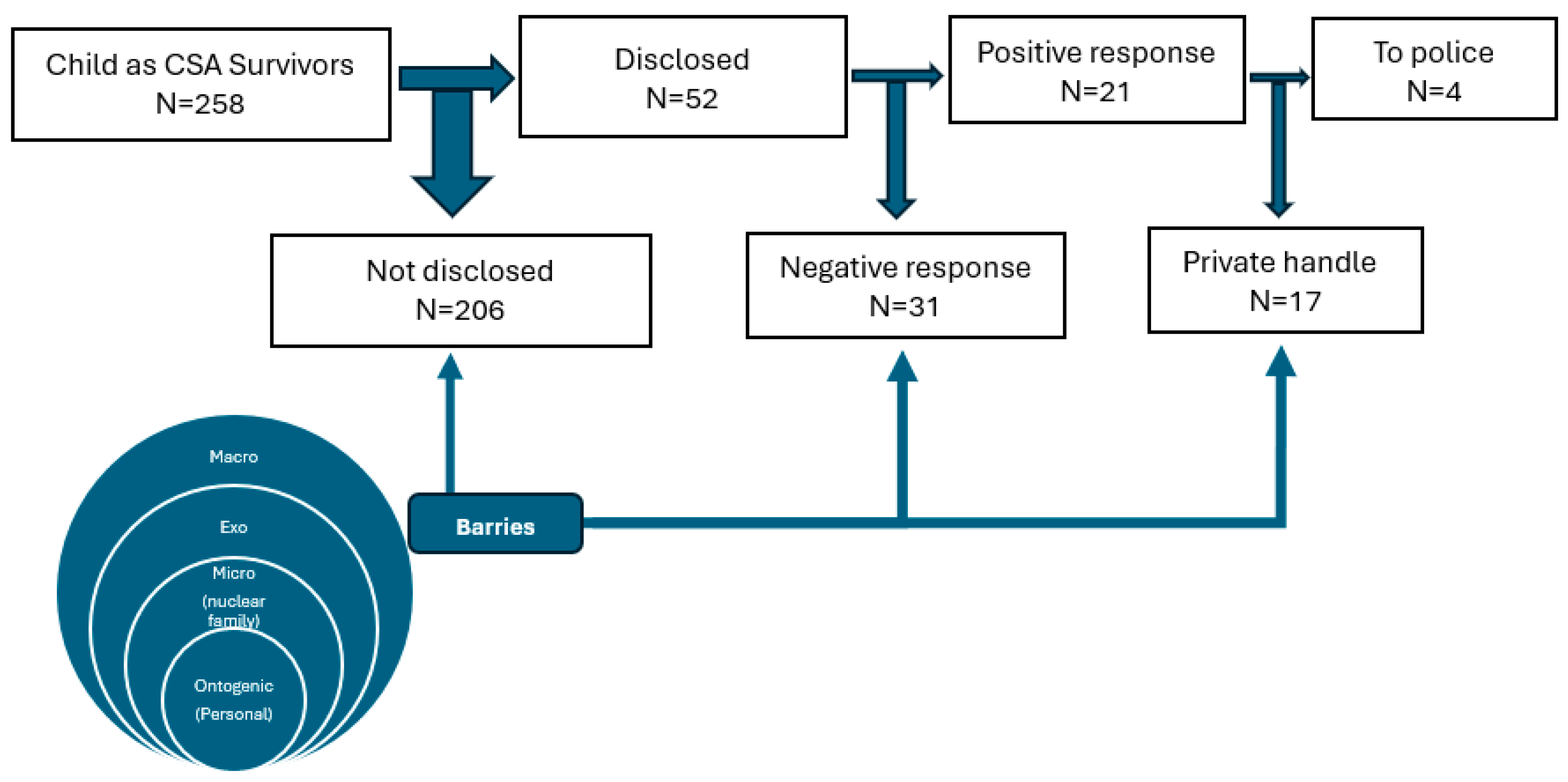

3. Findings

3.1. Barries to Disclose Child Sexual Abuse

3.1.1. Barriers at Individual Level (Ontogenic)

A Lack of Awareness of Sexual Abuse

“I did not tell my mum because I did not understand the meaning of his behaviours … I thought it was just normal (relationship with my brother). When I was 8 years old, I learned from school (physical hygiene education) that I should not have incest behaviours with my brother.”

Children’s Feeling of being Unsafe and Unprotected

“… I was afraid that my parents would know … In a word, I was afraid that the people around me would be hurt, but I forgot that I was the injured one. At that time, I was afraid of causing trouble for my family.”(Poster 8)

“As I gradually became aware of sexuality, I dared not discuss it with my feudal, conservative, and stubborn parents. Whenever we watched scenes involving kissing in movies, they would always make disapproving remarks, making me too afraid to bring up the topic …”

Children Incapable of Disclosing Sexual Abuse

3.1.2. Barries at Micro-Systems: Families

Parents’ Lack of Awareness

‘I actually feel repulsed by boys and have complete distrust towards them. However, my parents think that my lack of early romantic relationships is reassuring …’(Poster 142)

Complex Family Environment

3.1.3. Barriers at Exo-Systems: Extended Families, Neighbourhood, and Community

Worries of the Extended Family Relationship

Worries of Neighbourhood and Acquaintance Relationship

Lack of Support from Neighbourhoods and Communities

“No one helped me. The teacher dared not intervene, my aunt would not take action for me, and my parents were far away. Feeling helpless, I chose to endure it without external help. If you couldn’t endure it, and decided to fight back, the bullying and sexual harassment would only get worse … Because I was a child that nobody cared about and nobody protected.”(Poster 18)

“All the villagers knew that I was a left-behind child, many of them teased me: Your parents abandoned you. I was very young at that time, so I believed what they said. After I was raped, the perpetrators always threatened me: If you tell anyone, your parents will never come back, they also made me confirm that I would never tell anyone.”

3.1.4. Barriers in the Macro-System: Cultural, Value, and Social Factors

“I worry that he (the perpetrator) might expose this, tarnishing my reputation… After it’s exposed, I’ll be the only one suffering. Society is really unfriendly towards women.”(Poster 260)

3.2. Response to Disclosed and Exposed Cases of Child Sexual Abuse

3.2.1. Response to Disclosure

“I told my dad on the spot, but my stepmother scolded me, and my dad said you must have misunderstood.”(Poster 62)

3.2.2. Disclosure and Judicial Intervention

“my grandfather was kept at the police station for half a day, but because I had no visible injuries, it didn’t even qualify as a criminal case, allowing him to escape justice.”(Poster 86)

“If I had seen answers on Zhihu about collecting evidence in rape cases or something similar earlier, maybe I would have reported”(Poster 135);

“I remember my own aunt kneeling in front of my mother begging her not to report”(Poster 240);

“I wanted to, but I was too scared, too scared to report… the public opinion on this matter is too harsh, as a victim, I don’t have the strength to endure any more harm”(Poster 33).

3.2.3. Response Depend on Kinship Relations

4. Discussion

4.1. Conclusion and Policy Implications

4.2. Limitations and Significance of the Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hillis, S.; Mercy, J.; Amobi, A.; Kress, H. Global prevalence of past-year violence against children: A systematic review and minimum estimates. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20154079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltenborgh, M.; Van Ijzendoorn, M.H.; Euser, E.M.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J. A global perspective on child sexual abuse: Meta-analysis of prevalence around the world. Child Maltreat. 2011, 16, 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Fry, D.A.; Ji, K.; Finkelhor, D.; Chen, J.; Lannen, P.; Dunne, M.P. The burden of child maltreatment in China: A systematic review. Bull. World Health Organ. 2015, 93, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, K.; Finkelhor, D.; Dunne, M. Child sexual abuse in China: A meta-analysis of 27 studies. Child Abuse Negl. 2013, 37, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y. Prevalence of childhood sexual abuse in China: A meta-analysis. J. Child Sex. Abuse 2018, 27, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Zhang, S.H.; Yang, J.; Li, Y.; Ye, Y.F.; Dong, X.M.; Wang, S.Y. Meta-analysis on the incidence rates of child sexual abuse in China. Chin. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 34, 1245–1249. [Google Scholar]

- A Decade of Child Sexual Abuse Prevention in China (2013–2023)—A Civilian Perspective on “Protection of Girls”. Available online: https://www.all-in-one.org.cn/newsinfo/6188914.html (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- Analysis Report on Judicial Cases of CSA. Available online: http://weekly.pkulaw.cn/Admin/Content/Static/bfa50f54-13f8-4dc3-8cb6-2d8fb2a9750e.html (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- Martin, E.K.; Silverstone, P.H. How much child sexual abuse is “below the surface,” and can we help adults identify it early? Front. Psychiatry 2013, 4, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.S.-K. Childhood experience of sexual abuse among Hong Kong Chinese college students. Child Abuse Negl. 2002, 26, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.W.; Sun, X.; Chen, M.; Qiao, D.P.; Chan, K.L. What prevents Chinese parents from reporting possible cases of child sexual abuse to authority? A holistic-interactionistic approach. Child Abuse Negl. 2017, 64, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Tian, T.; He, X. Assessing attitudes towards child maltreatment among social workers in Mainland China. Youth Stud. 2021, 54–62, 95. [Google Scholar]

- Opinions on Establishing a Mandatory Reporting System for Cases against Minors (for Trial Implementation). Available online: https://www.spp.gov.cn/spp/xwfbh/wsfbt/202005/t20200529_463482.shtml#1 (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- Lovett, B.B. Child sexual abuse disclosure: Maternal response and other variables impacting the victim. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2004, 21, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin-Vézina, D.; De La Sablonnière-Griffin, M.; Palmer, A.M.; Milne, L. A preliminary mapping of individual, relational, and social factors that impede disclosure of childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 2015, 43, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcelvaney, R. Disclosure of child sexual abuse: Delays, non-disclosure and partial disclosure. What the research tells us and implications for practice. Child Abuse Rev. 2013, 24, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carretta, C.M.; Burgess, A.W.; Demarco, R. To tell or not to tell. Violence Against Women 2016, 22, 1499–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, S.E. Correlates of social reactions to victims’ disclosures of sexual assault and intimate partner violence: A systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse 2021, 24, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, S.E. Aspects of selective sexual assault disclosure: Qualitative interviews with survivors and their informal supports. J. Interpers. Violence 2023, 39, 263–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinzow, H.M.; Thompson, M. Barriers to reporting sexual victimization: Prevalence and correlates among undergraduate women. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2011, 20, 711–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, C.M.; Anderson, G.D.; Maclin, R. Why I didn’t report: Reasons for not reporting sexual violence as stated on Twitter. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2021, 31, 478–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaggia, R.; Wang, S. “I never told anyone until the #metoo movement”: What can we learn from sexual abuse and sexual assault disclosures made through social media? Child Abuse Negl. 2020, 103, 104312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’neil, A.; Sojo, V.; Fileborn, B.; Scovelle, A.J.; Milner, A. The #MeToo movement: An opportunity in public health? Lancet 2018, 391, 2587–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, J.E.; Fissel, E.R.; Hoxmeier, J.; Williams, E. # MeToo for whom? Sexual assault disclosures before and after# MeToo. Am. J. Crim. Justice 2021, 46, 68–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.-C.; Lam, G.L.T.; Shae, W.-C. Children’s views on child abuse and neglect: Findings from an exploratory study with Chinese children in Hong Kong. Child Abuse Negl. 2011, 35, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawrikar, P.; Katz, I. Barriers to disclosing child sexual abuse (CSA) in ethnic minority communities: A review of the literature and implications for practice in Australia. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 83, 302–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcguire, K.; London, K. A retrospective approach to examining child abuse disclosure. Child Abuse Negl. 2020, 99, 104263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilligan, P.; Akhtar, S. Child sexual abuse among Asian communities: Developing materials to raise awareness in Bradford. Practice 2005, 17, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.P.H. Editorial: Disclosure of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 2000, 24, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, A. The victim’s experience: Pathways to disclosure. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. Train. 1991, 28, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaggia, R. Many ways of telling: Expanding conceptualizations of child sexual abuse disclosure. Child Abuse Negl. 2004, 28, 1213–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summit, R.C. Abuse of the child sexual abuse accommodation syndrome. J. Child Sex. Abuse 1993, 1, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, M.; Wehrspann, W.; Klajner-Diamond, H.; Lebaron, D.; Winder, C. Review of 125 children 6 years of age and under who were sexually abused. Child Abuse Negl. 1986, 10, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauzier, M. Disclosure of child sexual abuse. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 1989, 12, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitsema, A.M.; Grietens, H. Is anybody listening? The literature on the dialogical process of child sexual abuse disclosure reviewed. Trauma Violence Abuse 2015, 17, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allnock, D.; Miller, P. No One Noticed, No One Heard: A Study of Disclosures of Childhood Abuse; NSPCC: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky, J. Child maltreatment: An ecological integration. Am. Psychol. 1980, 35, 320–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaggia, R. An ecological analysis of child sexual abuse disclosure: Considerations for child and adolescent mental health. J. Can. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2010, 19, 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Tat, M.C.; Ozturk, A. Ecological system model approach to self-disclosure process in child sexual abuse. Curr. Approaches Psychiatry 2019, 11, 363–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaggia, R.; Collin-Vézina, D.; Lateef, R. Facilitators and barriers to child sexual abuse (CSA) disclosures: A research update (2000–2016). Trauma Violence Abuse 2017, 20, 260–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Population Statues of Children in China in 2015: Facts and Figures. Available online: https://www.unicef.cn/reports/population-status-children-china-2015 (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- Paine, M.L.; Hansen, D.J. Factors influencing children to self-disclose sexual abuse. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2002, 22, 271–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Chen, J.; Feng, Y.; Li, J.; Zhao, X.; Luo, X. Young children’s knowledge and skills related to sexual abuse prevention: A pilot study in Beijing, China. Child Abuse Negl. 2013, 37, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, H.; Wan, G.; Sun, X.; Niu, J. A scoping review of programs to prevent child sexual abuse in Mainland China. Trauma Violence Abuse 2022, 24, 3647–3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zeng, S. Sexuality education for children and youth with disabilities in Mainland China: Systematic review of thirty years. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 116, 105197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Dunne, M.P.; Han, P. Prevention of child sexual abuse in China: Knowledge, attitudes, and communication practices of parents of elementary school children. Child Abuse Negl. 2007, 31, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.W.; Qiao, D.P.; Wang, X.L. Parent-involved prevention of child sexual abuse: A qualitative exploration of parents’ perceptions and practices in Beijing. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015, 25, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.; Xia, Y. The changes in mainland Chinese families during the social transition: A critical analysis. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 2014, 45, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Ren, P.; Yin, G.; Li, H.; Jin, Y. Sexual abuse prevention education for preschool-aged children: Parents’ attitudes, knowledge and practices in Beijing, China. J. Child Sex. Abuse 2020, 29, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obong’o, C.O.; Patel, S.N.; Cain, M.; Kasese, C.; Mupambireyi, Z.; Bangani, Z.; Pichon, L.C.; Miller, K.S. Suffering whether you tell or don’t tell: Perceived re-victimization as a barrier to disclosing child sexual abuse in Zimbabwe. J. Child Sex. Abuse 2020, 29, 944–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.; Bryant-Davis, T.; Tillman, S.; Marks, A. Stifled voices: Barriers to help-seeking behavior for South African childhood sexual assault survivors. J. Child Sex. Abuse 2010, 19, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, I.; Shang, X.; Cui, Y. The challenge of Defining Child Sexual Abuse in the Developing Child Protection System in China. Int. J. Child Maltreat. Res. Policy Pract. 2021, 4, 401–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Wang, X.; Li, J. Knowledge transmission and skills building relating to child sexual abuse in China. J. Child Sex. Abuse 2023, 32, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X.; Hamilton, G.G.; Zheng, W. From the Soil: The Foundations of Chinese Society; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Long, D. Child Sexual Abuse: Shame or Hurt—An Exploratory Study the Experiences of Rural Chinese Families Facing an Extra-Familial Child Sexual Abuse Problem upon Disclosure; Guangxi Normal University Press: Guilin, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, L.; Corral, S.; Bradley, C.; Fisher, H.; Bassett, C.; Howat, N.; Collishaw, S. Child Abuse and Neglect in the UK Today; NSPCC: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fontes, L.A.; Plummer, C. Cultural issues in disclosures of child sexual abuse. J. Child Sex. Abuse 2010, 19, 491–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, G.M.; Colombino, N.; Schaaf, S.; Laake, A.L.W.; Jeglic, E.L.; Calkins, C. Why do child sexual abuse victims not tell anyone about their abuse? An exploration of factors that prevent and promote disclosure. Behav. Sci. Law 2020, 38, 586–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, M.-H. Identifying key components of an internet information system for Chinese survivors of childhood sexual abuse. J. Ethnic Cult. Divers. Soc. Work 2013, 22, 256–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age of Initial Abuse | Gender and Number | Number of Perpetrators and Victims | Instance of Abuse | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | N | N | Perpetrators (N) | Victims (N) | N | ||

| 3–6 years | 66 | Male | 38 | One | 197 | Once | 95 |

| 7–12 years | 133 | Female | 220 | Multiple | 61 | Repeated | 163 |

| 13–15 years | 29 | ||||||

| 16–18 years | 4 | ||||||

| Unknown | 26 | ||||||

| Total | 258 | 258 | 258 | 258 | |||

| Age Group | Gender | Relationship to Victims | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N | N | |||

| Adults | 165 | Male | 330 | Strangers | 42 |

| Minors | 174 | Female | 23 | Acquaintances | 165 |

| Unknown | 14 | Relatives | 146 | ||

| Identity of Perpetrator | To Whom Abuse Was Disclosed | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | N * | ||

| Relatives | 22 | Mother | 25 |

| Acquaintance | 13 | Father | 12 |

| Stranger | 3 | Grandmother | 5 |

| Sister/brother | 2 | ||

| Friend/boyfriend | 3 | ||

| Teacher | 2 | ||

| Stranger | 1 | ||

| Response after Disclosure | Voluntary Disclosure | Passive Disclosure | In Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Disclosed Cases | Caught in The Act | Other Informed | ||

| Calling the police | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Directly beating or scolding the perpetrator | 7 | 3 | 0 | 10 |

| Prohibiting the perpetrator from contacting the victim | 4 | 2 | 1 | 7 |

| Comforting the child, but took no further action (seen as negative as well) | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Providing no support (contains laughing at the victim, standing on the perpetrator’s side, not believing, scolding the victim and no response) | 20 | 3 | 3 | 26 |

| Total | 38 | 10 | 4 | 52 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tian, T.; Katz, I.; Shang, X. Unveiling Child Sexual Abuse Disclosure in China: An Ecological Exploration of Survivors’ Experiences. Children 2024, 11, 688. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11060688

Tian T, Katz I, Shang X. Unveiling Child Sexual Abuse Disclosure in China: An Ecological Exploration of Survivors’ Experiences. Children. 2024; 11(6):688. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11060688

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Tian, Ilan Katz, and Xiaoyuan Shang. 2024. "Unveiling Child Sexual Abuse Disclosure in China: An Ecological Exploration of Survivors’ Experiences" Children 11, no. 6: 688. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11060688

APA StyleTian, T., Katz, I., & Shang, X. (2024). Unveiling Child Sexual Abuse Disclosure in China: An Ecological Exploration of Survivors’ Experiences. Children, 11(6), 688. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11060688