Who Benefits Most from the Family Education and Support Program in Cape Verde? A Cluster Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Analysis Plan

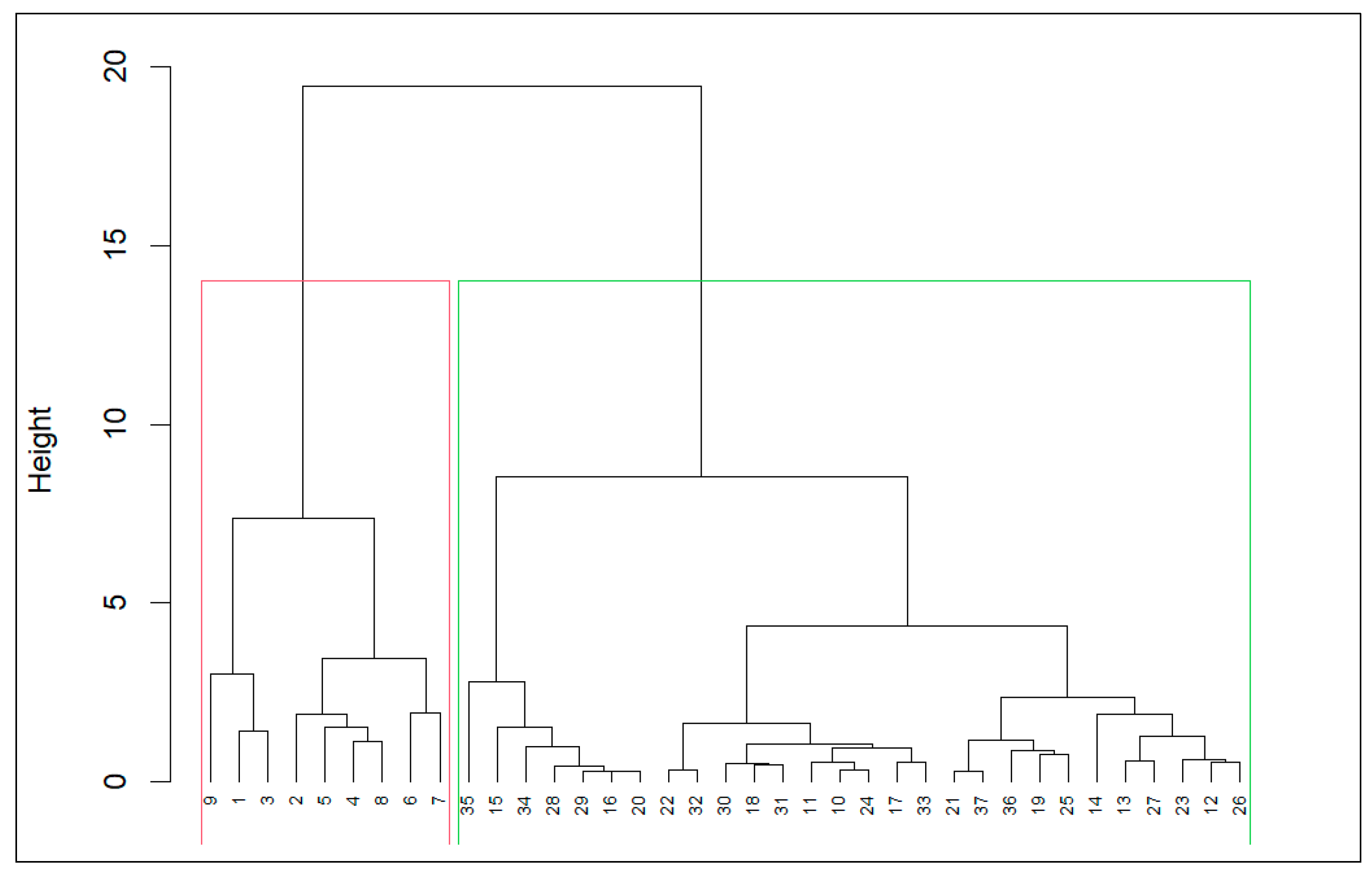

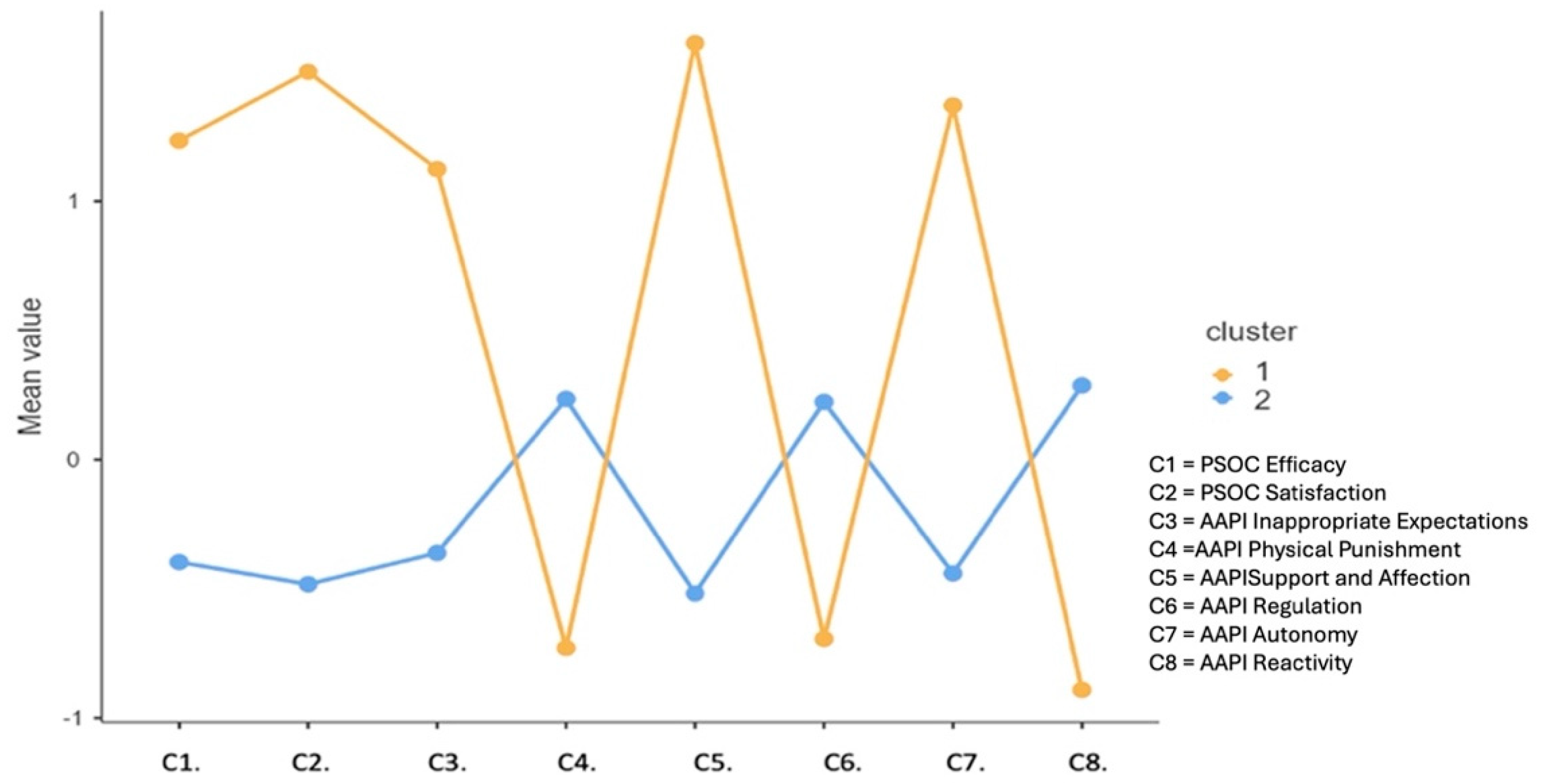

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Studies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ayala-Nunes, L.; Jiménez, L.; Jesus, S.; Nunes, C.; Hidalgo, V. An Ecological Model of Well-Being in Child Welfare Referred Children. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 140, 811–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Children’s Fund [UNICEF]. Fair Parent, Fair Child: Handbook on Positive Parenting; UNICEF Office: Skopje, Macedonia, 2018; Available online: https://www.unicef.mk (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- García-Poole, C.; Byrne, S.; Rodrigo, M.J. Implementation Factors that Predict Positive Outcomes in a Community-based Intervention Program for at-Risk Adolescents. Psychosoc. Interv. 2019, 28, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, M.V.; Ruiz, B.; Bacete, F.J.; González, R.A.; Verdugo, I.; Jiménez, L. The Evaluation of Family Support Programmes in Spain. An Analysis of their Quality Standards. Psicol. Educ. 2023, 29, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.; Martins, C.; Brás, M.; Carmo, C.; Gonçalves, A.; Pina, A. Impact of an online parenting support programme on children’s quality of life. Children 2022, 9, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Children’s Fund [UNICEF]. O Cuidado Integral e a Parentalidade Positiva na Primeira Infância. Brasília: Fundo das Nações Unidas para a Infância; Fundo das Nações Unidas para a Infância (UNICEF): Brasília, Brazil, 2023; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/brazil/biblioteca (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Hidalgo, V.; Jiménez, L. Os Programas de Educação e Apoio Parental Como Recurso para a Promoção da Parentalidade Positiva com Famílias em Situação de Risco Psicossocial. In Famílias em Risco: Avaliação e Intervenção Psicoeducativa; Nunes, C., Ayala, L., Eds.; Silabas & Desafios: Faro, Portugal, 2019; pp. 173–203. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, L.; Hidalgo, M. La Incorporación de Prácticas Basadas en Evidencias en el Trabajo con Familias: Los Programas de Promoción de Parentalidad Positiva. Apunt. Psicol. 2017, 34, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.; Ayala-Nunes, L. Parenting sense of competence in at psychosocial risk families and child well-being. Bordón 2017, 69, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, M.J.; Almeida, A.; Reichle, B. Evidence-Based Parent Education Programs: A European Perspective. In Evidence-Based Parenting Education: A Global Perspective; Ponzetti, J., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- Altafim, E.; Linhares, M. Universal violence and child maltreatment prevention programs for parents: A systematic review. Psychosoc. Interv. 2016, 25, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.; Matavelli, R.; Cunha, F.F.; Hidalgo, V.; Jesus, S.N.; Nunes, C. Family Education and support programme: Implementation and cultural adaptation in Cape Verde. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikton, C.; Butchart, A. Child maltreatment prevention: A systematic review of reviews. Bull. World Health Organ. 2009, 87, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M.R.; Higgins, D.; Prinz, R. A population approach to the prevention of child maltreatment: Rationale and implications for research, policy and practice. Fam. Matters 2018, 100, 62–70. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Recommendation Rec(2006)7 of the Committee of Ministers to Member States on Management of Patient Safety and Prevention of Adverse Events in Health Care 2006. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/portal/home (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Avezum, M.; Altafim, E.; Linhares, M. Spanking and corporal punishment parenting practices and child development: A systematic review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2023, 24, 3094–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuartas, J.; Weissman, D.; Sheridan, M.; Lengua, L.; McLaughlin, K. Corporal Punishment and Elevated Neural Response to Threat in Children. Child Dev. 2021, 92, 821–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotto, C.; Altafim, E.; Linhares, M. Maternal history of childhood adversities and later negative parenting: A systematic review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2023, 24, 662–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, C.; Ayala-Nunes, L.; Nunes, C.; Pechorro, P.; Costa, E.; Matos, F. Confirmatory analysis of the Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PSDQ) short form in a portuguese sample. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2018, 11, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.; Bodden, D.; Lemos, I.; Lorence, B.; Jiménez, L. Parenting practices and quality of life in Dutch and Portuguese adolescents: A cross-cultural study. Rev. Psicodidact. 2014, 19, 327–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macana, E.; Comim, F. O papel das práticas e estilos parentais no desenvolvimento da primeira infância. In Fundamentos da Família como Promotora do Desenvolvimento Infantil: Parentalidade em Foco; Pluciennik, G., Lazzari, M., Chicaro, M., Eds.; Fundação Maria Cecilia Souto Vidigal: São Paulo, Brazil, 2015; pp. 34–47. [Google Scholar]

- Goagoses, N.; Bolz, T.; Eilts, J.; Schipper, N.; Schütz, J.; Rademacher, A.; Vesterling, C.; Koglin, U. Parenting dimensions/styles and emotion dysregulation in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 18798–18822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, M.H. Determinants of parenting. In Developmental Psychopathology: Risk, Resilience, and Intervention, 3rd ed.; Cicchetti, D., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 4, pp. 180–270. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, C.; Martins, C.; Ayala-Nunes, L.; Matos, F.; Costa, E.; Gonçalves, A. Parents’ perceived social support and children’s psychological adjustment. J. Soc. Work. 2021, 21, 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsky, J.; Jaffee, S.R. The multiple determinants of parenting. In Developmental Psychopathology, 2nd ed.; Cicchetti, D., Cohen, D., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 38–77. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky, J. The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Dev. 1984, 55, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershoff, E.T.; Lee, S.J.; Durrant, J.E. Promising intervention strategies to reduce parents’ use of physical punishment. Child Abus. Negl. 2017, 71, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilmann, A.; Mehay, A.; Watt, R.G.; Kelly, Y.; Durrant, J.E.; van Turnhout, J.; Gershoff, E.T. Physical punishment and child outcomes: A narrative review of prospective studies. Lancet 2021, 398, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, I.; Garcia, O.F.; Alcaide, M.; Garcia, F. Positive parenting style and positive health beyond the authoritative: Self, universalism values, and protection against emotional vulnerability from Spanish adolescents and adult children. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1066282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes, M.; Garcia, O.F.; Perez-Gramaje, A.F.; Serra, E.; Melendez, J.C.; Alcaide, M.; Garcia, F. Which is the optimum parenting for adolescents with low vs. high self-efficacy? Self-concept, psychological maladjustment and academic performance of adolescents in the Spanish context. An. Psicol./Ann. Psychol. 2023, 39, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, Y.; Veiga, F.; Fuentes, M.C.; García, F. Parenting and adolescents’ self-esteem: The Portuguese context. Rev. Psicodidact. 2013, 18, 395–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bølstad, E.; Havighurst, S.S.; Tamnes, C.K.; Nygaard, E.; Bjørk, R.F.; Stavrinou, M.; Espeseth, T. A pilot study of a parent emotion socialization intervention: Impact on parent behavior, child self-regulation, and adjustment. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 730278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwairy, M.; Achoui, M. Adolescents-family connectedness: A first cross-cultural research on parenting and psychological adjustment of children. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2010, 19, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, T.; Cerqueira, A.; Guedes, F.B.; de Matos, M.G. Parental Emotional Support, Family Functioning and Children’s Quality of Life. Psychol. Stud. 2022, 67, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M. Associations of parenting dimensions and styles with externalizing problems of children and adolescents: An updated meta-analysis. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 53, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, K.; Sharon, R.; Ghazarian, S.; Little, T.; Leventhal, T. Understanding links between punitive parenting and adolescent adjustment: The relevance of context and reciprocal associations. J. Adolesc. Res. 2010, 21, 448–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker-Henningham, H.; Francis, T. Parents’ use of harsh punishment and young children’s behaviour and achievement: A longitudinal study of Jamaican children with conduct problems. Glob. Ment. Health 2018, 5, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmann, L.; Bergmann, M.C.; Fischer, F.; Mößle, T. Risk and protective factors of child-to-parent violence: A comparison between physical and verbal aggression. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP1309–NP1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.C.; Palumbo, I.M.; Tobin, K.E.; Latzman, R.D. Exploring the effects of parental involvement on broad and specific dimensions of behavioral problems in adolescence. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2022, 53, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez Ruíz, M.M.; Carrasco, M.Á.; Holgado-Tello, F.P. Father involvement and children’s psychological adjustment: Maternal and paternal acceptance as mediators. J. Fam. Stud. 2019, 25, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitnick, S.; Shaw, D.; Gill, A.; Dishion, T.; Winter, C.; Waller, R.; Gardner, F.; Wilson, M. Parenting and the Family Check-Up: Changes in observed parent-child interaction following early childhood intervention. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2015, 44, 970–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, R.; Goh, D. Authoritarian parenting style in Asian societies. A cluster-analytic investigation. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 2006, 28, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamborn, S.; Dornbusch, S.; Stein-berg, L. Ethnicity and com-munity context as moderators of the relations between family decision making and adolescent adjustment. Child Dev. 1996, 67, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.; Cruz, O. Atitudes e estilos parentais em mãe de crianças com processo de promoção e proteção. Rev. Amaz. 2012, 8, 310–337. [Google Scholar]

- Black, D.; Heyman, R.; Smith Slep, A. Risk factors for child physical abuse. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2001, 6, 121–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Albeniz, A.; de Paul, J. Gender diferences in empathy in parents at high- and low-risk of child physical abuse. Child Abus. Negl. 2004, 28, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bavolek, S.; Keene, R. Adult-Adolescent Parenting Inventory. AAPI—2: Assessing High-Risk Parenting Attitudes and Behaviors; Family Development Resources, Inc.: Park City, UT, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Aparício, G.; Cunha, M.; Duarte, J. Self-perception of parental competence in parents of pre-school children. Aten. Prim. 2016, 48, 247–252. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, T.; Prinz, R. Potential roles of parental self-efficacy in parent and child adjustment: A review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2005, 25, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Nunes, L.; Nunes, C.; Lemos, I. Social support and parenting stress in at-risk Portuguese families. J. Soc. Work. 2017, 17, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.; Ayala-Nunes, L.; Ferreira, L.; Pechorro, P.; Freitas, D.; Martins, C.; Santos, R. Parenting sense of competence: Psychometrics and invariance among community and at-risk sample of Portuguese parents. Healthcare 2023, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauch, J.; Hefti, S.; Oeltjen, L.; Pérez, T.; Swenson, C.C.; Fürstenau, U.; Rhiner, B.; Schmid, M. Multisystemic therapy for child abuse and neglect: Parental stress and parental mental health as predictors of change in child neglect. Child Abus. Negl. 2022, 126, 105489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayala-Nunes, L.; Lemos, I.; Nunes, C. Predictores del estrés parental en madres de familias en riesgo psicosocial. Univ. Psychol. 2014, 13, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, J.; Nunes, L.; Victoria, M.V.; Nunes, C.; Lemos, I.; Menéndez, S. Parenting and stress: A study with Spanish and Portuguese at-risk families. Int. Soc. Work. 2017, 60, 1001–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.M. Parentalidade na infância: Relação com a parentalidade e qualidade de vida atual [Childhood Parenting: Relationship with Parenting and Current Quality of Life]. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Lusófona de Humanidades e Tecnologias, Lisboa, Portugal, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Feniger-Schaal, R.; Joels, T. Attachment quality of children with ID and its link to maternal sensitivity and structuring. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2018, 76, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, M. Harnessing the power of positive parenting to promote wellbeing of children, parents and communities over a lifetime. Behav. Change 2019, 36, 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.; Nunes, C.; Marotta, G.; Lopes, M.; Martins, C.; Hidalgo, V.; Jesus, S. Impacto do programa de formação e apoio familiar nas competências parentais e na qualidade de vida infantil percebida em Cabo-Verde. Psychologica 2024, 67, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M.R. Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: Towards an empirically validated multilevel parenting and family support strategy for the prevention of behavior and emotional problems in children. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 1999, 2, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, F.; Burton, J.; Klimes, I. Randomised controlled trial of a parenting intervention in the voluntary sector for reducing child conduct problems: Outcomes and mechanisms of change. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2006, 47, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorós-Martí, P.; Byrne, S.; Mateos-Inchaurrondo, A.; Vaquero-Tió, E.; Mundet-Bolós, A. “Learning together, growing with family”: The implementation and evaluation of a family support programme. Psychosoc. Interv. 2016, 25, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knerr, W.; Gardner, F.; Cluver, L. Improving positive parenting skills and reducing harsh and abusive parenting in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Prev. Sci. 2013, 14, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo, M.V.; Menéndez Álvarez-Dardet, S.; Sánchez Hidalgo, J.; Lorence Lara, B.; Jiménez, L. La intervención con familias en situación de riesgo psicosocial: Aportaciones desde un enfoque psicoeducativo. Apunt. Psicol. 2009, 27, 413–426. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, M.V.; Menéndez, S.; López, I.; Sánchez, J.; Lorence, B.; Jiménez, L. Programa de Formación y Apoyo Familiar; Ayuntamiento de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, M.V.; Jiménez, L.; López-Verdugo, I.; Lorence, B.; Sánchez, J. “Family education and support” program for families at psychosocial risk: The role of implementation process. Psychosoc. Interv. 2016, 25, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, V.; Sanchez, J.; Lorence, B.; Menendez, S.; Jiménez, L. Evaluación de la implementación del programa de formación y apoyo familiar en servicios sociales. Escr. Psicol. 2014, 7, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maya, J.; Hidalgo, M.V. Evaluación de la implementación del Programa de Formación y Apoyo Familiar con familias peruanas. Apunt. Psicol. 2016, 34, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, M.V.; Menéndez, S.; López, I.; Sánchez, J.; Lorence, B.; Jiménez, L. Programa de Formação e Apoio Familiar; Nunes, C., Martins, C., Ayala-Nunes, L., Gonçalves, A., Eds.; Universidade do Algarve: Faro, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman, J.M.; Cluver, L.; Ward, C.L.; Hutchings, J.; Mlotshwa, S.; Wessels, I.; Gardner, F. Randomized controlled trial of a parenting program to reduce the risk of child maltreatment in South Africa. Child Abus. Negl. 2017, 72, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachman, J.M.; Kelly, J.; Cluver, L.; Ward, C.L.; Hutchings, J.; Gardner, F. Process evaluation of a parenting program for low-income families in South Africa. Res. Social. Work. Prac. 2018, 28, 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J.; Roman, N.; Mwaba, K. Circle of Security parenting program efficacy for improving parental self-efficacy in a South African setting: Preliminary evidence. J. Psychol. Afr. 2018, 28, 518–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zand, D.H.; Bultas, M.W.; McMillin, S.E.; Halloran, D.; White, T.; McNamara, D.; Pierce, K.J. A pilot of a brief positive parenting program on children newly diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Fam. Process 2018, 57, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, K.M.; Thurston, I.B.; Howell, K.H.; Hasselle, A.J.; Kamody, R.C. Associations between Profiles of Maternal Strengths and Positive Parenting Practices among Mothers Experiencing Adversity. Parenting 2021, 21, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWayne, C.M.; Mattis, J.S.; Hyun, S. Profiles of culturally salient positive parenting practices among urban-residing Black Head Start families. Cultur. Divers. Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 2018, 24, 414–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, M.V.; Menéndez, S.; Sánchez, J.; López, I.; Jiménez, L.; Lorence, B. Inventario de Situaciones Estresantes y de Riesgo (ISER); University of Seville: Seville, Spain, 2005; Unpublished Document. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, C.; Lemos, I.; Ayala-Nunes, L.; Costa, D. Acontecimentos de vida stressantes e apoio social em famílias em risco psicossocial. Psicol. Saúde Doenças 2013, 14, 313–320. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/362/36227023008.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Johnston, C.; Mash, E.J. A measure of parenting satisfaction and efficacy. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 1989, 18, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.; Williams, P. Cuestionario de Salud General GHQ (General Health Questionnaire): Guía para el Usuario de las Distintas Versiones; Masson: Barcelona, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Pais-Ribeiro, J.L.; Antunes, S. Contribuição para o estudo de adaptação do questionário de saúde geral de 28 itens (General Health Questionnaire—GHQ28). Rev. Port. Psicossomática 2003, 5, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- The KIDSCREEN Group Europe. The KIDSCREEN Questionnaires: Quality of Life Questionnaires for Children and Adolescents; Pabst Science Publishers: Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar, T.; Matos, M.G. Qualidade de vida em Crianças e Adolescentes: Versão Portuguesa dos Instrumentos KIDSCREEN-52; Aventura Social e Saúde: Cruz e Quebrada, Portugal, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, C.; Mandleco, B.; Olsen, S.; Hart, C.H. The Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PSDQ). In Handbook of Family Measurement Techniques; Perlmutter, B., Touliatos, J., Holden, G., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001; Volume 3, pp. 319–321. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, D.; O’Leary, S.; Wolff, L.; Acker, M. The Parenting Scale: A measure of dysfunctional parenting in discipline situations. Psychol. Assess. 1993, 5, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, B.K. Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. Child Dev. 1996, 67, 3296–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, I.; Brandão, T. AAPI—2, Versão de Investigação, Traduzida e Adaptada para Português Europeu; Universidade Técnica de Lisboa: Lisbon, Portugal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, G.; Pihur, V.; Datta, S.; Datta, S. clValid: An R Package for Cluster Validation. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 25, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Core Team, R. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [Computer Software]; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Handl, J.; Knowles, J.; Kell, B.D. Computational cluster validation in post-genomic data analysis. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 3201–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.C. Well separated clusters and fuzzy partitions. J. Cybern. 1974, 4, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseeuw, P.J. Silhouettes: A graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 1987, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.; Datta, S. Comparisons and validation of statistical clustering techniques for microarray gene expression data. Bioinformatics 2003, 19, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freire, T.; S Almeida, L.S. Metodologia da Investigação em Psicologia e Educação; Psiquilibrios: Braga, Portugal, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, L.M.; Janta, B.; Gardner, F. Positive Parenting Interventions: Empowering Parents with Positive Parenting Techniques for Lifelong Health and Well–Being; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, M.V. Procesos de innovación y mejora en el ámbito de la intervención familiar. El papel de las y los profesionales en la incorporación de buenas prácticas basadas en la evidencia. Apunt. Psicol. 2022, 40, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axford, N.; Lehtonen, M.; Kaoukji, D.; Tobin, K.; Berry, V. Engaging parents in parenting programs: Lessons from research and practice. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2012, 34, 2061–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenderovich, Y.; Eisner, M.; Cluver, L.; Doubt, J.; Berezin, M.; Majokweni, S.; Murray, A.L. Delivering a parenting program in South Africa: The impact of implementation on outcomes. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 1005–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, H.H.V.S.; Noronha, A.P.P.; Reppold, C.T. Associações entre forças de caráter e estilos parentais em adultos. Rev. Psicol. Pesq. 2022, 16, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littell, J.; Schuerman, J. What works best for whom? A closer look at intensive family preservation services. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2002, 24, 673–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flay, B.; Biglan, A.; Boruch, R.F.; González, F.; Gottfredson, D.; Kellam, S.; Moscicki, E.; Schinke, S.; Valentine, J.C.; Ji, P. Standards of evidence: Criteria for efficacy, effectiveness and dissemination. Prev. Sci. 2005, 6, 151–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachman, J.M.; Sherr, L.T.; Cluver, L.; Ward, C.L.; Hutchings, J.; Gardner, F. Integrating evidence and context to develop a parenting program for low-income families in South Africa. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016, 25, 2337–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrelly, A.C.; McLennan, J.D. Participation in a parent education programme in the Dominican Republic: Utilization and barriers. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2010, 56, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.; Nunes, L.A. Famílias em risco psicossocial: Desafios para a avaliação e intervenção. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2015, 6, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, A.; Daniels, K.; Tomlinson, M. Children’s experiences of corporal punishment: A qualitative study in an urban township of South Africa. Child Abus. Negl. 2015, 48, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cluver, L.D.; Meinck, F.; I Steinert, J.; Shenderovich, Y.; Doubt, J.; Romero, R.H.; Lombard, C.J.; Redfern, A.; Ward, C.L.; Tsoanyane, S.; et al. Parenting for Lifelong Health: A pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial of a non-commercialised parenting programme for adolescents and their families in South Africa. BMJ Glob. Health 2018, 3, e000539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez, L.; Antolín-Suárez, L.; Lorence, B.; Hidalgo, V. Family education and support for families at psychosocial risk in Europe: Evidence from a survey of international experts. Health Soc. Care Community 2019, 27, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Validation Measures | Optimal Score | Method | Clusters | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal | Connectivity | 6.691 | Diana | 2 |

| Dunn Index | 0.439 | Diana | 3 | |

| Silhouette | 0.525 | Diana | 2 | |

| Stability | APN | 0.007 | Hierarchical | 2 |

| AD | 1.389 | Sota | 3 | |

| ADM | 0.023 | Hierarchical | 2 | |

| FOM | 0.400 | Sota | 3 | |

| Domains | Categories | Cluster 1 (n = 9) | Cluster 2 (n = 28) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f | % | f | % | ||||||

| Assistance Group | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.60 | ||||

| 2 | 1 | 11.10 | 10 | 35.70 | |||||

| 3 | 8 | 88.90 | 8 | 28.60 | |||||

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 32.10 | |||||

| Education Level | Primary | 5 | 55.50 | 53 | 53.50 | ||||

| Secondary | 3 | 33.30 | 8 | 28.60 | |||||

| Higher education | 1 | 11.10 | 5 | 17.90 | |||||

| Family Type | Monoparental | 3 | 33.30 | 5 | 17.90 | ||||

| Biparental | 6 | 66.70 | 20 | 71.40 | |||||

| Sex of the child | Female | 3 | 33.30 | 14 | 50.00 | ||||

| Male | 6 | 66.70 | 14 | 50.00 | |||||

| M | SD | Min | Max | M | SD | Min | Max | ||

| Age of the child | 8.33 | 2.50 | 6.00 | 12.00 | 8.79 | 2.23 | 6.00 | 12.00 | |

| Mental health | 44.22 | 8.81 | 33.00 | 62.00 | 48.07 | 8.77 | 32.00 | 64.00 | |

| Child Quality of Life | 3.70 | 0.38 | 2.80 | 4.00 | 3.86 | 0.28 | 2.90 | 4.30 | |

| Domains | Cluster 1 (n = 9) | Cluster 2 (n = 28) | Z | p | r | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | Min | Max | M | SD | Min | Max | ||||

| Efficacy | 1.02 | 0.37 | 0.43 | 1.57 | 0.23 | 0.33 | −0.57 | 1.14 | −3.98 | <0.001 | 0.65 |

| Satisfaction | 1.35 | 0.62 | 0.22 | 2.22 | 0.06 | 0.17 | −0.22 | 0.44 | −4.32 | <0.001 | 0.71 |

| Inap. Exp. | 1.30 | 1.11 | −0.14 | 2.86 | 0.13 | 0.34 | −0.29 | 1.29 | −3.18 | 0.001 | 0.52 |

| Physical Punishment | −0.56 | 1.01 | −2.00 | 1.09 | 0.02 | 0.29 | −0.64 | 0.91 | −1.70 | 0.088 | 0.28 |

| Affection and Support | 1.18 | 0.35 | 0.80 | 2.00 | 0.06 | 0.12 | −0.20 | 0.40 | −4.77 | <0.001 | 0.78 |

| Regulation | −2.04 | 0.51 | −2.80 | −1.20 | −1.29 | 0.83 | −3.00 | 0.20 | −2.51 | 0.012 | 0.41 |

| Autonomy | 0.93 | 0.52 | 0.20 | 1.80 | 0.04 | 0.21 | −0.80 | 0.40 | −4.59 | <0.001 | 0.75 |

| Reactivity | −0.62 | 0.83 | −2.40 | 0.00 | −0.06 | 0.13 | −0.40 | 0.20 | −2.51 | 0.012 | 0.41 |

| Dimensions | C1 | C2 | Z | p | r | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| Efficacy | 4.32 | 0.25 | 4.31 | 0.49 | −0.27 | 0.789 | 0.04 |

| Satisfaction | 3.57 | 0.48 | 3.50 | 0.50 | −0.28 | 0.776 | 0.05 |

| Quality of Life | 3.70 | 0.38 | 3.86 | 0.28 | −1.33 | 0.183 | 0.22 |

| Parental Mental Health | 44.22 | 8.81 | 48.07 | 8.77 | −1.45 | 0.146 | 0.24 |

| Inappropriate Expectations | 2.40 | 0.71 | 2.15 | 0.66 | −1.14 | 0.255 | 0.19 |

| Physical Punishment | 2.77 | 0.63 | 2.71 | 0.68 | −0.21 | 0.831 | 0.04 |

| Affection and Support | 3.76 | 0.36 | 3.95 | 0.43 | −1.13 | 0.259 | −0.19 |

| Regulation | 3.84 | 0.51 | 3.96 | 0.30 | −0.72 | 0.475 | −0.12 |

| Autonomy | 3.58 | 0.42 | 3.50 | 0.47 | −0.41 | 0.680 | −0.07 |

| Reactivity | 2.42 | 0.83 | 2.74 | 0.79 | −1.16 | 0.248 | −0.19 |

| Domains | Cluster 1 (n = 9) | Z | p | r | Cluster 2 (n = 28) | Z | p | r | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |||||||||||||||||||

| M | SD | Min | Max | M | SD | Min | Max | M | SD | Min | Max | M | SD | Min | Max | |||||||

| No. of sessions | - | - | - | - | 7.78 | 2.44 | 3.00 | 10.00 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 7.96 | 2.56 | 3.00 | 12.00 | - | - | - |

| Efficacy | 4.32 | 0.25 | 4.00 | 4.71 | 5.33 | 0.29 | 4.86 | 5.71 | −2.67 | 0.008 | 0.47 | 4.31 | 0.49 | 3.14 | 5.43 | 4.55 | 0.41 | 3.57 | 5.29 | −3.17 | 0.002 | 0.56 |

| Satisfaction | 3.57 | 0.48 | 3.00 | 4.44 | 4.91 | 0.47 | 4.11 | 5.56 | −2.67 | 0.008 | 0.47 | 3.50 | 0.50 | 2.67 | 4.67 | 3.56 | 0.46 | 2.67 | 4.78 | −1.66 | 0.097 | 0.29 |

| Quality of Life | 3.70 | 0.38 | 2.80 | 4.00 | 4.52 | 0.28 | 4.20 | 5.00 | 2.67 | 0.008 | 0.47 | 3.86 | 0.28 | 2.90 | 4.30 | 3.96 | 0.32 | 2.80 | 4.50 | −3.03 | 0.002 | 0.54 |

| Parental Mental Health | 44.22 | 8.81 | 33.00 | 62.00 | 47.78 | 2.82 | 44.00 | 53.00 | −1.87 | 0.236 | 0.33 | 48.07 | 8.77 | 32.00 | 64.00 | 48.04 | 8.29 | 33.00 | 64.00 | −0.87 | 0.385 | 0.15 |

| Inappropriate Expectations | 2.40 | 0.71 | 1.43 | 3.29 | 3.70 | 0.49 | 3.00 | 4.43 | −2.94 | 0.013 | 0.52 | 2.15 | 0.66 | 1.14 | 3.29 | 2.29 | 0.71 | 1.14 | 3.57 | −2.20 | 0.028 | 0.39 |

| Physical Punishment | 2.77 | 0.63 | 2.00 | 3.55 | 2.21 | 0.67 | 1.18 | 3.18 | −1.60 | 0.109 | 0.28 | 2.71 | 0.68 | 1.73 | 4.09 | 2.73 | 0.58 | 1.73 | 4.00 | −0.51 | 0.609 | 0.09 |

| Affection and Support | 3.76 | 0.36 | 3.00 | 4.20 | 4.93 | 0.14 | 4.60 | 5.00 | −2.69 | 0.007 | 0.48 | 3.95 | 0.43 | 3.00 | 5.00 | 4.01 | 0.38 | 3.00 | 4.80 | −2.50 | 0.013 | 0.44 |

| Regulation | 3.84 | 0.51 | 3.00 | 4.60 | 4.87 | 0.22 | 4.40 | 5.00 | −2.68 | 0.007 | 0.47 | 3.96 | 0.30 | 3.20 | 4.80 | 4.01 | 0.30 | 3.40 | 4.80 | −2.83 | 0.005 | 0.50 |

| Autonomy | 3.58 | 0.42 | 2.80 | 4.00 | 4.51 | 0.39 | 4.00 | 5.00 | −2.67 | 0.008 | 0.47 | 3.50 | 0.47 | 2.40 | 4.20 | 3.54 | 0.47 | 2.40 | 4.20 | −1.65 | 0.098 | 0.29 |

| Reactivity | 2.42 | 0.83 | 1.40 | 3.60 | 1.80 | 0.46 | 1.20 | 2.40 | −2.21 | 0.027 | 0.39 | 2.74 | 0.79 | 1.00 | 3.80 | 2.67 | 0.78 | 1.00 | 3.80 | −2.31 | 0.021 | 0.41 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Correia, A.; Martins, C.; Santos, R.d.; Hidalgo, V.; Jesus, S.N.d.; Nunes, C. Who Benefits Most from the Family Education and Support Program in Cape Verde? A Cluster Analysis. Children 2024, 11, 782. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11070782

Correia A, Martins C, Santos Rd, Hidalgo V, Jesus SNd, Nunes C. Who Benefits Most from the Family Education and Support Program in Cape Verde? A Cluster Analysis. Children. 2024; 11(7):782. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11070782

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorreia, Adriana, Cátia Martins, Rita dos Santos, Victoria Hidalgo, Saúl Neves de Jesus, and Cristina Nunes. 2024. "Who Benefits Most from the Family Education and Support Program in Cape Verde? A Cluster Analysis" Children 11, no. 7: 782. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11070782