Assessment of Psychosocial Stress and Mental Health Disorders in Parents and Their Children in Early Childhood: Cross-Sectional Results from the SKKIPPI Cohort Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

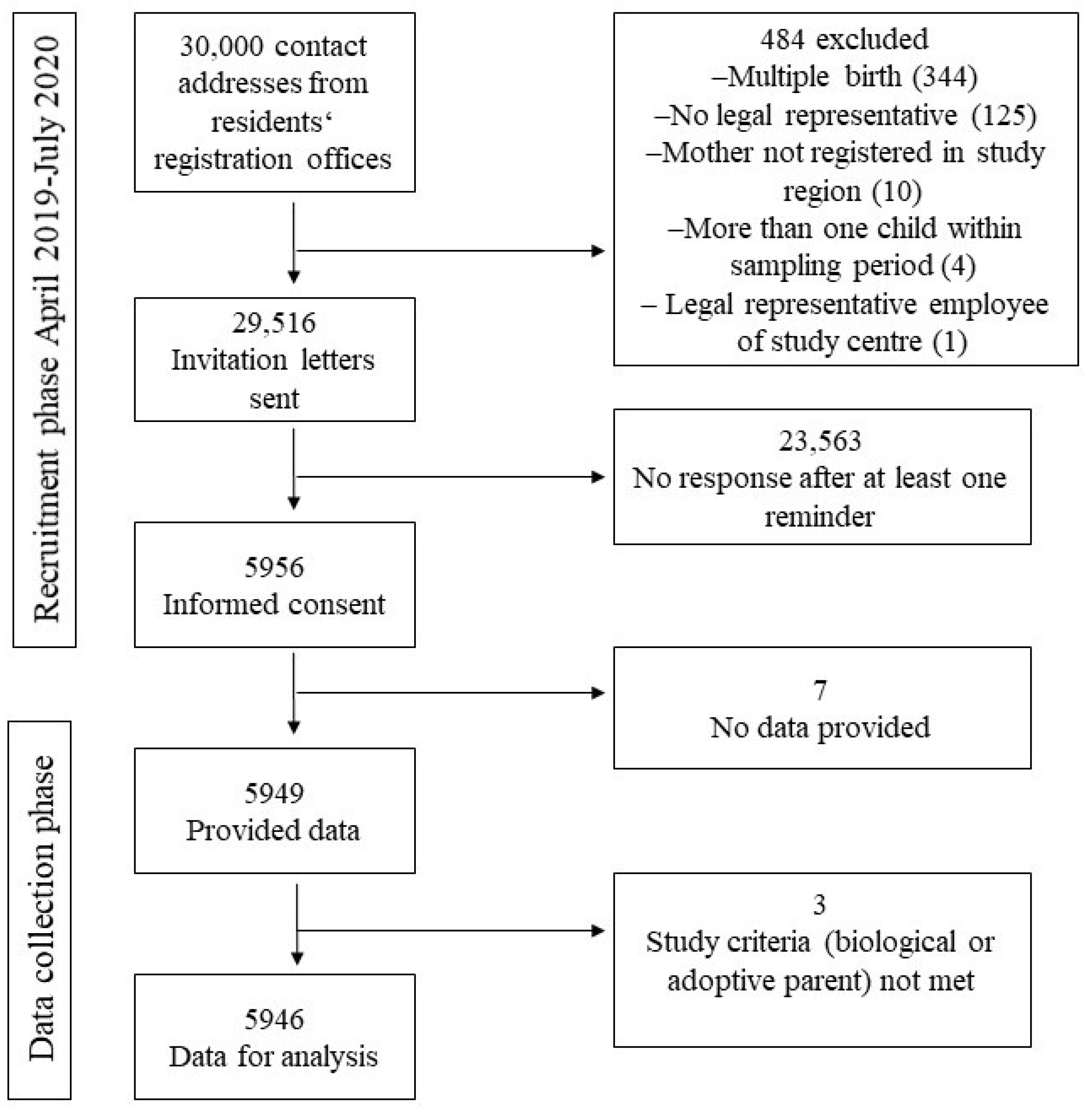

3.1. Participants

3.2. Sociodemographic Characteristics

3.3. Perinatal Stressors and Characteristics

3.4. Individual Parental Stressors

3.5. Mental Health Problems of the Parents and the Child

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Comparison with Other Studies

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ramchandani, P.; Stein, A.; Evans, J.; O’Connor, T.G.; the ALSPAC Study Team. Paternal Depression in the Postnatal Period and Child Development: A Prospective Population Study. Lancet 2005, 365, 2201–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ainsworth, M.D.S.; Bell, S.M.; Stayton, D.F. Infant-Mother Attachment and Social Development: Socialization as a Product of Reciprocal Responsiveness to Signals. In The Integration of a Child into a Social World; Richards, M.P.M., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974; pp. 99–135. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, A.S.; Garrity-Rokous, F.E.; Chazan-Cohen, R.; Little, C.; Briggs-Gowan, M.J. Maternal Depression and Comorbidity: Predicting Early Parenting, Attachment Security, and Toddler Social-Emotional Problems and Competencies. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2001, 40, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, K.E.; Grossmann, K. The Development of Psychological Security in Attachment—Results and Conclusions for Therapy. Z. Psychosom. Med. Psychother. 2007, 53, 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Papousek, H.; Papousek, M. Structure and Dynamics of Human Communication at the Beginning of Life. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Neurol. Sci. 1986, 236, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonagy, P.; Cottrell, D.; Phillips, J.; Bevington, D.; Glaser, D.; Allison, E. What Works for Whom?: A Critical Review of Treatments for Children and Adolescents, 2nd ed.; Guilford Publications: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Petzoldt, J.; Wittchen, H.U.; Wittich, J.; Einsle, F.; Hofler, M.; Martini, J. Maternal Anxiety Disorders Predict Excessive Infant Crying: A Prospective Longitudinal Study. Arch. Dis. Child 2014, 99, 800–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemmi, M.H.; Wolke, D.; Schneider, S. Associations between Problems with Crying, Sleeping and/or Feeding in Infancy and Long-Term Behavioural Outcomes in Childhood: A Meta-Analysis. Arch. Dis. Child 2011, 96, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyons-Ruth, K. Contributions of the Mother-Infant Relationship to Dissociative, Borderline, and Conduct Symptoms in Young Adulthood. Infant. Ment. Health J. 2008, 29, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briggs-Gowan, M.J.; Carter, A.S.; Skuban, E.M.; Horwitz, S.M. Prevalence of Social-Emotional and Behavioral Problems in a Community Sample of 1-and 2-Year-Old Children. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2001, 40, 811–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprengeler, M.K.; Mattheß, J.; Galeris, M.G.; Eckert, M.; Koch, G.; Reinhold, T.; Berghöfer, A.; Fricke, J.; Roll, S.; Keil, T.; et al. Being an Infant in a Pandemic: Influences of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Infants, Toddlers and Their Mothers in a Clinical Population. Children 2023, 10, 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifin, S.R.M.; Cheyne, H.; Maxwell, M. Review of the Prevalence of Postnatal Depression across Cultures. AIMS Public Health 2018, 5, 260–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.L.; Falah-Hassani, K.; Shiri, R. Prevalence of Antenatal and Postnatal Anxiety: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2017, 210, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn-Holbrook, J.; Cornwell-Hinrichs, T.; Anaya, I. Economic and Health Predictors of National Postpartum Depression Prevalence: A Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression of 291 Studies from 56 Countries. Front. Psychiatry 2017, 8, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, J.; Petzoldt, J.; Knappe, S.; Garthus-Niegel, S.; Asselmann, E.; Wittchen, H.U. Infant, Maternal, and Familial Predictors and Correlates of Regulatory Problems in Early Infancy: The Differential Role of Infant Temperament and Maternal Anxiety and Depression. Early Hum. Dev. 2017, 115, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skovgaard, A.M.; Houmann, T.; Christiansen, E.; Landorph, S.; Jorgensen, T.; Team, C.C.C.S.; Olsen, E.M.; Heering, K.; Kaas-Nielsen, S.; Samberg, V.; et al. The Prevalence of Mental Health Problems in Children 1(1/2) Years of Age—The Copenhagen Child Cohort 2000. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2007, 48, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wake, M.; Morton-Allen, E.; Poulakis, Z.; Hiscock, H.; Gallagher, S.; Oberklaid, F. Prevalence, Stability, and Outcomes of Cry-Fuss and Sleep Problems in the First 2 Years of Life: Prospective Community-Based Study. Pediatrics 2006, 117, 836–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, E.E.; Sedov, I.D.; Tomfohr-Madsen, L.M. Prevalence of Paternal Depression in Pregnancy and the Postpartum: An Updated Meta-Analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 206, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reck, C.; Struben, K.; Backenstrass, M.; Stefenelli, U.; Reinig, K.; Fuchs, T.; Sohn, C.; Mundt, C. Prevalence, Onset and Comorbidity of Postpartum Anxiety and Depressive Disorders. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2008, 118, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buechel, C.; Friedmann, A.; Eber, S.; Behrends, U.; Mall, V.; Nehring, I. The Change of Psychosocial Stress Factors in Families with Infants and Toddlers During the Covid-19 Pandemic. A Longitudinal Perspective on the Coronababy Study from Germany. Front. Pediatr. 2024, 12, 1354089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buechel, C.; Nehring, I.; Seifert, C.; Eber, S.; Behrends, U.; Mall, V.; Friedmann, A. A Cross-Sectional Investigation of Psychosocial Stress Factors in German Families with Children Aged 0–3 Years During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Initial Results of the Coronababy Study. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2022, 16, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, C.T. Predictors of Postpartum Depression: An Update. Nurs. Res. 2001, 50, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clout, D.; Brown, R. Sociodemographic, Pregnancy, Obstetric, and Postnatal Predictors of Postpartum Stress, Anxiety and Depression in New Mothers. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 188, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Hara Michael, W.; Swain, A.M. Rates and Risk of Postpartum Depression—A Meta-Analysis. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2009, 8, 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, S.; Ulrich, S.M.; Sann, A.; Liel, C. Self-Reported Psychosocial Stress in Parents with Small Children—Results from the Kinder in Deutschland–Kid-0–3 Study. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2020, 117, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fricke, J.; Bolster, M.; Ludwig-Korner, C.; Kuchinke, L.; Schlensog-Schuster, F.; Vienhues, P.; Reinhold, T.; Berghofer, A.; Roll, S.; Keil, T. Occurrence and Determinants of Parental Psychosocial Stress and Mental Health Disorders in Parents and Their Children in Early Childhood: Rationale, Objectives, and Design of the Population-Based Skkippi Cohort Study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2021, 56, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckert, M.; Mattheß, J.; Fricke, J.; Richter, K.; Sprengeler, M.; Koch, G.; Roll, S.; Bolster, M.; Berghöfer, A.; Reinhold, T.; et al. Evaluation Der Eltern-Säugling-Kleinkind-Psychotherapie Mittels Prävalenz- Und Interventionsstudien (Skkippi). In DGPPN Kongress 2019; Psychosomatik und Nervenheilkunde Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, Ed.; Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Nervenheilkunde: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mattheß, J.; Eckert, M.; Richter, K.; Koch, G.; Reinhold, T.; Vienhues, P.; Berghöfer, A.; Roll, S.; Keil, T.; Schlensog-Schuster, F.; et al. Efficacy of Parent-Infant-Psychotherapy with Mothers with Postpartum Mental Disorder: Study Protocol of the Randomized Controlled Trial as Part of the Skkippi Project. Trials 2020, 21, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprengeler, M.K.; Mattheß, J.; Eckert, M.; Richter, K.; Koch, G.; Reinhold, T.; Vienhues, P.; Berghöfer, A.; Fricke, J.; Roll, S.; et al. Efficacy of Parent-Infant Psychotherapy Compared to Care as Usual in Children with Regulatory Disorders in Clinical and Outpatient Settings: Study Protocol of a Randomised Controlled Trial as Part of the Skkippi Project. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattheß, J.; Koch, G.; Keil, T.; Roll, S.; Berghöfer, A.; Ludwig-Körner, C.; Schlensog-Schuster, F.; Sprengeler, M.K.; von Klitzing, K.; Kuchinke, L. Past Attachment Experiences, the Potential Link of Mentalization and the Transmission of Behavior to the Child by Mothers with Mental Health Problems: Cross-Sectional Analysis of a Clinical Sample. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 33, 1883–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghöfer, A.; Göckler, D.G.; Sydow, J.; Auschra, C.; Wessel, L.; Gersch, M. The German Health Care Innovation Fund—An Incentive for Innovations to Promote the Integration of Health Care. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2020, 34, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Initiative, S. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (Strobe) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stith, S.M.; Liu, T.; Davies, L.C.; Boykin, E.L.; Alder, M.C.; Harris, J.M.; Som, A.; McPherson, M.; Dees, J.E.M.E.G. Risk Factors in Child Maltreatment: A Meta-Analytic Review of the Literature. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2009, 14, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löwe, B.; Wahl, I.; Rose, M.; Spitzer, C.; Glaesmer, H.; Wingenfeld, K.; Schneider, A.; Brahler, E. A 4-Item Measure of Depression and Anxiety: Validation and Standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (Phq-4) in the General Population. J. Affect. Disord. 2010, 122, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fineberg, N.; Robert, A. Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: A Twentyfirst Century Perspective. In Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: A Practical Guide; Fineberg, N., Marazziti, D., Stein, D.J., Eds.; Martin Dunitz: London, UK, 2001; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesinitiative Frühe Hilfen. Kid 0-3: Ein Fragebogen Zur Situation Von Familien Mit Säuglingen Und Kleinkindern in Deutschland. [Kid 0-3: A Questionnaire on the Situation of Families with Infants and Toddlers in Germany]. 2013. Available online: https://www.fruehehilfen.de (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Groß, S.; Reck, C.; Thiel-Bonney, C.; Cierpka, M. Empirische Grundlagen des Fragebogens Zum Schreien, Füttern und Schlafen (Sfs). Prax. Kinderpsychol. Kinderpsychiat. 2013, 62, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert Koch-Institut. Daten Und Fakten: Ergebnisse Der Studie “Gesundheit in Deutschland Aktuell 2012”. In Beiträge zur Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes; Robert-Koch Institut, Ed.; RKI: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schipf, S.; Schöne, G.; Schmidt, B.; Günther, K.; Stübs, G.; Greiser, K.H.; Bamberg, F.; Meinke-Franze, C.; Becher, H.; Berger, K.; et al. The Baseline Assessment of the German National Cohort (Nako Gesundheitsstudie): Participation in the Examination Modules, Quality Assurance, and the Use of Secondary Data. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2020, 63, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis). Daten Zum Durchschnittlichen Alter der Eltern Bei Geburt Nach der Geburtenfolge Für 1. Kind, 2. Kind, 3. Kind der Mutter und Insgesamt 2020. Statistisches Bundesamt. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Geburten/Tabellen/geburten-eltern-biologischesalter.html (accessed on 22 July 2021).

- Lenze, A.; Funcke, A.; Menne, S. Factsheet Alleinerziehende in Deutschland; Bertelsmann Stiftung: Gütersloh, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Melchior, M.; Caspi, A.; Milne, B.J.; Danese, A.; Poulton, R.; Moffitt, T.E. Work Stress Precipitates Depression and Anxiety in Young, Working Women and Men. Psychol. Med. 2007, 37, 1119–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.L.; Lesage, A.; Schmitz, N.; Drapeau, A. The Relationship between Work Stress and Mental Disorders in Men and Women: Findings from a Population-Based Study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2008, 62, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, B.; Milgrom, J. Risk Factors for Antenatal Depression, Postnatal Depression and Parenting Stress. BMC Psychiatry 2008, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wosu, A.C.; Gelaye, B.; Williams, M.A. History of Childhood Sexual Abuse and Risk of Prenatal and Postpartum Depression or Depressive Symptoms: An Epidemiologic Review. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2015, 18, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, B.T. Parent Distraction with Phones, Reasons for Use, and Impacts on Parenting and Child Outcomes: A Review of the Emerging Research. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2019, 1, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.; Blackie, M.; Nedeljkovic, M. Fathers’ Experience of Perinatal Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms: A Systematic Literature Review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 24, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudepohl, N.; MacLean, J.V.; Osborne, L.M. Perinatal Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Epidemiology, Phenomenology, Etiology, and Treatment. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2022, 24, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballestrem, C.L.V.; Strauss, M.; Kachele, H. Contribution to the Epidemiology of Postnatal Depression in Germany--Implications for the Utilization of Treatment. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2005, 8, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert Koch-Institut. Depressive Symptoms in a European Comparison—Results from the European Health Interview Survey (Ehis) 2. J. Health Monit. 2019, 4, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Galea, S.; Tracy, M. Participation Rates in Epidemiologic Studies. Ann. Epidemiol. 2007, 17, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobsen, T.N.; Nohr, E.A.; Frydenberg, M. Selection by Socioeconomic Factors into the Danish National Birth Cohort. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 25, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mothers n (%) | Fathers n (%) | Full Sample n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study site | 4984 | 962 | 5946 |

| 3963 (79.5) | 745 (77.4) | 4708 (79.2) |

| 67 (1.3) | 14 (1.5) | 81 (1.4) |

| 813 (16.3) | 171 (17.8) | 984 (16.5) |

| 141 (2.8) | 32 (3.3) | 173 (2.9) |

| Age group | 4984 | 962 | 5946 |

| 778 (15.6) | 88 (9.1) | 866 (14.6) |

| 3708 (74.4) | 649 (67.5) | 4357 (73.3) |

| 497 (10.0) | 203 (21.1) | 700 (11.8) |

| 1 (0.0) | 22 (2.3) | 23 (0.4) |

| Country of birth | 4946 | 936 | 5882 |

| 4190 (84.7) | 786 (84.0) | 4976 (84.6) |

| 756 (15.3) | 150 (16.0) | 906 (15.4) |

| Native language | 4945 | 935 | 5880 |

| 4232 (85.6) | 796 (85.1) | 5028 (85.5) |

| German language skills (if not native German, self-assessment) | 711 | 139 | 850 |

| 557 (78.3) | 99 (71.2) | 656 (77.2) |

| 100 (14.1) | 20 (14.4) | 120 (14.1) |

| 54 (7.6) | 20 (14.4) | 74 (8.7) |

| Educational level | 4944 | 935 | 5879 |

| 24 (0.5) | 7 (0.7) | 31 (0.5) |

| 695 (14.1) | 127 (13.6) | 822 (14.0) |

| 4196 (84.9) | 796 (85.1) | 4992 (84.9) |

| 29 (0.6) | 5 (0.5) | 34 (0.6) |

| Current partner/relationship | 4970 | 950 | 5920 |

| 4749 (95.6) | 947 (99.7) | 5696 (96.2) |

| Single parent | 4943 | 935 | 5878 |

| 289 (5.8) | 7 (0.7) | 296 (5.0) |

| Number of children < 18 y in household (including index child) | 4945 | 934 | 5879 |

| 111 (2.2) | 19 (2.0) | 130 (2.2) |

| 2640 (53.4) | 563 (60.3) | 3203 (54.5) |

| 1692 (34.2) | 265 (28.4) | 1957 (33.3) |

| 502 (10.2) | 87 (9.3) | 589 (10.0) |

| Receiving government benefit payments | 4940 | 936 | 5885 |

| 653 (13.2) | 83 (8.9) | 736 (12.5) |

| Support through early intervention programs | 4943 | 935 | 5878 |

| 727 (14.7) | 156 (16.7) | 883 (15.0) |

| Mothers n (%) | Fathers n (%) | Full Sample n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Index child diagnosed with a serious illness or disability after birth or in the first few months of life | 4977 | 954 | 5931 |

| 180 (3.6) | 30 (3.1) | 210 (3.5) |

| Other child in household with a serious illness or disability | 4940 | 935 | 5875 |

| 111 (2.2) | 28 (3.0) | 139 (2.4) |

| Relationship with the child (‘I feel close to my child …’) | 4972 | 950 | 5922 |

| 3918 (78.8) | 685 (72.1) | 4603 (77.7) |

| 1000 (20.1) | 249 (26.2) | 1249 (21.1) |

| 48 (1.0) | 15 (1.6) | 63 (1.1) |

| 6 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 7 (0.1) |

| 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Severe, negative experiences in own childhood | 4944 | 938 | 5882 |

| 1064 (21.5) | 150 (16.0) | 1214 (20.6) |

| Excessive preoccupation with diet and weight | 4950 | 938 | 5888 |

| 705 (14.2) | 66 (7.0) | 771 (13.1) |

| Current burdensome (chronic) illness | 4947 | 936 | 5883 |

| 377 (7.6) | 80 (8.5) | 457 (7.8) |

| Use of digital media: ‘I feel stressed if my child seeks my attention while I am using my smartphone/tablet.’ | 4968 | 948 | 5916 |

| 785 (15.8) | 153 (16.1) | 938 (15.9) |

| Use of digital media: ‘When I feed or play with my child, I use my smartphone/tablet …’ | 4972 | 950 | 5922 |

| 1411 (28.4) | 302 (31.8) | 1713 (28.9) |

| 2119 (42.6) | 396 (41.7) | 2515 (42.5) |

| 1253 (25.2) | 224 (23.6) | 1477 (24.9) |

| 189 (3.8) | 28 (2.9) | 217 (3.7) |

| Mothers n (%) | Fathers n (%) | Full Sample n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Occurrence of parental mental health disorders (lifetime) | 4940 | 935 | 5875 |

| 3886 (78.7) | 825 (88.2) | 4711 (80.2) |

| 4951 | 937 | 5888 |

| 738 (14.9) | 69 (7.4) | 807 (13.7) |

| 282 (5.7) | 31 (3.3) | 313 (5.3) |

| 35 (0.7) | 7 (0.7) | 42 (0.7) |

| 16 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 17 (0.3) |

| Occurrence of parental mental health problems (current situation) | |||

| Depressive Symptoms (PHQ-2) | 4955 | 944 | 5899 |

| 458 (9.2) | 84 (8.9) | 542 (9.2) |

| Anxiety symptoms (GAD-2) | 4953 | 944 | 5897 |

| 537 (10.8) | 70 (7.4) | 607 (10.3) |

| Alcohol problems | 4951 | 938 | 5889 |

| 15 (0.3) | 9 (1.0) | 24 (0.4) |

| Drug problems | 4950 | 937 | 5887 |

| 9 (0.2) | 5 (0.5) | 14 (0.2) |

| Obsessive–compulsive thoughts | 4948 | 938 | 5886 |

| 1054 (21.3) | 145 (15.5) | 1199 (20.4) |

| Obsessive–compulsive acts | 4951 | 938 | 5889 |

| 271 (5.5) | 60 (6.4) | 331 (5.6) |

| Mood swings and difficulties in controlling feelings | 4946 | 935 | 5881 |

| 982 (19.9) | 110 (11.8) | 1092 (18.6) |

| Regulatory Problem | Mothers n (%) | Fathers n (%) | Full Sample n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feeding problems | 4972 | 945 | 5917 |

| 71 (1.4) | 20 (2.1) | 91 (1.5) |

| Excessive crying | 4972 | 950 | 5922 |

| 151 (3.0) | 20 (2.1) | 171 (2.9) |

| Difficulties in falling asleep | 4973 | 950 | 5923 |

| 171 (3.4) | 45 (4.7) | 216 (3.6) |

| Difficulties in maintaining sleep | 4973 | 950 | 5923 |

| 246 (4.9) | 59 (6.2) | 305 (5.1) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fricke, J.; Bolster, M.; Icke, K.; Lisewski, N.; Kuchinke, L.; Ludwig-Körner, C.; Schlensog-Schuster, F.; Reinhold, T.; Berghöfer, A.; Roll, S.; et al. Assessment of Psychosocial Stress and Mental Health Disorders in Parents and Their Children in Early Childhood: Cross-Sectional Results from the SKKIPPI Cohort Study. Children 2024, 11, 920. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11080920

Fricke J, Bolster M, Icke K, Lisewski N, Kuchinke L, Ludwig-Körner C, Schlensog-Schuster F, Reinhold T, Berghöfer A, Roll S, et al. Assessment of Psychosocial Stress and Mental Health Disorders in Parents and Their Children in Early Childhood: Cross-Sectional Results from the SKKIPPI Cohort Study. Children. 2024; 11(8):920. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11080920

Chicago/Turabian StyleFricke, Julia, Marie Bolster, Katja Icke, Natalja Lisewski, Lars Kuchinke, Christiane Ludwig-Körner, Franziska Schlensog-Schuster, Thomas Reinhold, Anne Berghöfer, Stephanie Roll, and et al. 2024. "Assessment of Psychosocial Stress and Mental Health Disorders in Parents and Their Children in Early Childhood: Cross-Sectional Results from the SKKIPPI Cohort Study" Children 11, no. 8: 920. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11080920