Child Migrants in Family Detention in the US: Addressing Fragmented Care

Abstract

1. Introduction

Detention of Children in the US

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Size and Setting

2.2. Data Collection and Measures Used

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethical Review

3. Results

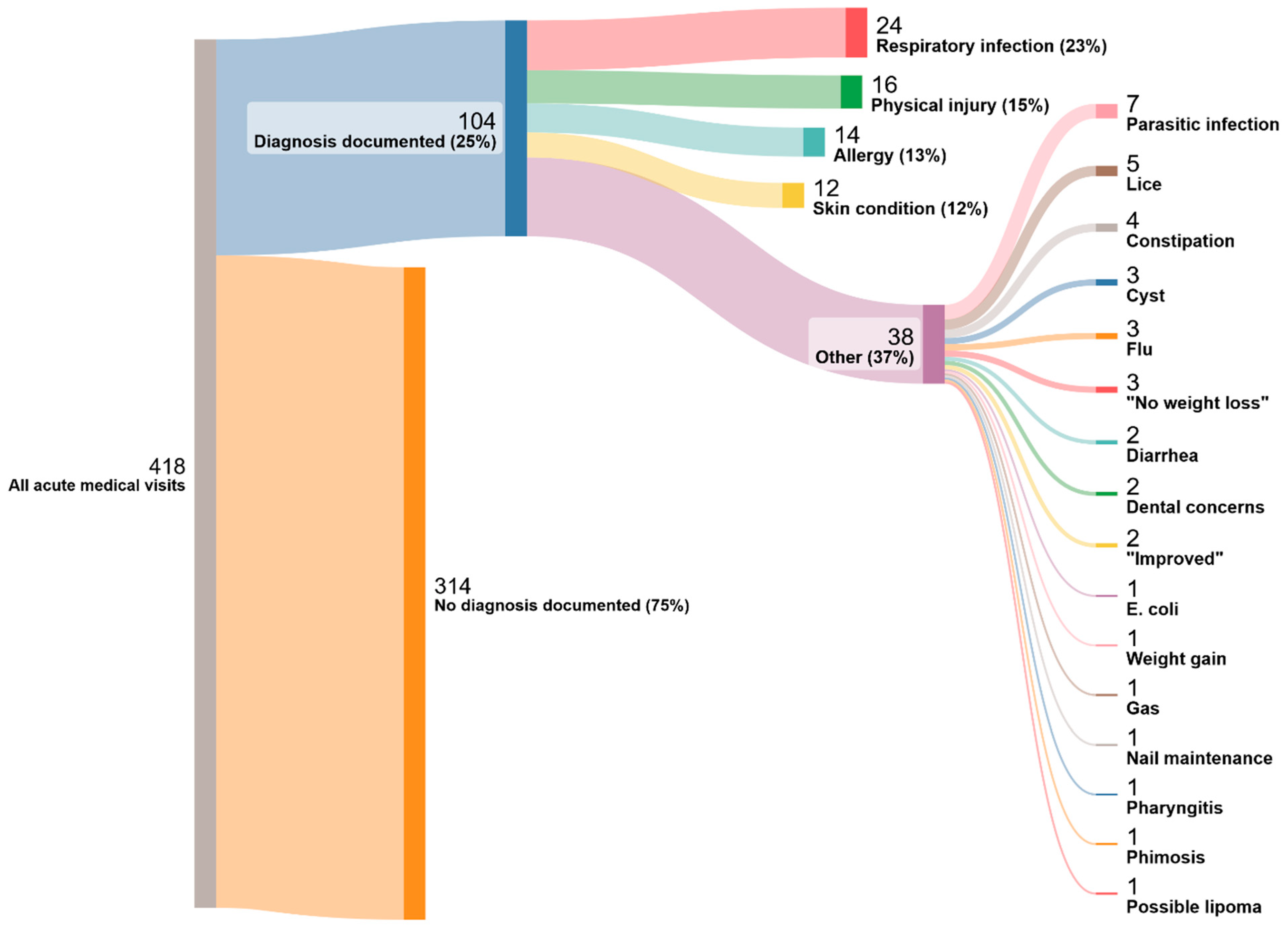

Medical Care

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdelrahman, W.; Abdelmageed, A. Medical record keeping: Clarity, accuracy, and timeliness are essential. Br. Med. J. 2014, 348, f7716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baauw, A.; Rosiek, S.; Slattery, B.; Chinapaw, M.; Van Hensbroek, M.B.; Van Goudoever, J.B.; Kist-van Holthe, J. Pediatrician-experienced barriers in the medical care for refugee children in the Netherlands. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2018, 177, 995–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeidan, A.J.; Goodall, H.; Sieben, A.; Parmar, P.; Burner, E. Medical Mismanagement in Southern US Immigration and Customs Enforcement Detention Facilities: A Thematic Analysis of Secondary Medical Records. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2023, 25, 1085–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erfani, P.; Uppal, N.; Lee, C.H.; Mishori, R.; Peeler, K.R. COVID-19 Testing and Cases in Immigration Detention Centers, April-August 2020. JAMA 2020, 325, 182–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dekker, A.M.; Farah, J.; Parmar, P.; Uner, A.B.; Schriger, D.L. Emergency Medical Responses at US Immigration and Customs Enforcement Detention Centers in California. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2345540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Praying for Hand Soap and Masks. PHR. Available online: https://phr.org/our-work/resources/praying-for-hand-soap-and-masks/ (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- UNHCR. Convention on the Rights of the Child General Comment No. 6 (2005): Treatment of Unaccompanied and Separated Children outside of Their Country of Origin. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/media/convention-rights-child-general-comment-no-6-2005-treatment-unaccompanied-and-separated (accessed on 6 May 2024).

- United Nations Task Force on Children Deprived of Liberty. United Nations. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/media/151371/file/Advocacy%20Brief:%20End%20Child%20Immigration%20Detention%20.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2023).

- Advocacy Brief: End Immigration Detention of Children (February 2024)—World | ReliefWeb. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/advocacy-brief-end-immigration-detention-children-february-2024 (accessed on 24 March 2024).

- Admin. Detention Watch Network. Family Detention. 2016. Available online: https://www.detentionwatchnetwork.org/issues/family-detention (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Linton, J.M.; Griffin, M.; Shapiro, A.J.; Council on Community Pediatrics; Chilton, L.A.; Flanagan, P.J.; Dilley, K.J.; Duffee, J.H.; Green, A.E.; Gutierrez, J.R.; et al. Detention of Immigrant Children. Pediatrics 2017, 139, e20170483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flagg, A.; Preston, J. In Border Cells Built for Adults, One-Third Are Child Migrants. Available online: https://www.themarshallproject.org/2022/06/16/no-place-for-a-child (accessed on 24 March 2024).

- The Flores Settlement. Immigration History. Available online: https://immigrationhistory.org/item/the-flores-settlement/ (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- US Immigration and Customs Enforcement. U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcment Health Service Corps Annual Report FY 2020. Available online: https://www.ice.gov/doclib/ihsc/IHSCFY20AnnualReport.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2023).

- 2011 Operations Manual ICE Performance-Based National Detention Standards | ICE. Available online: https://www.ice.gov/detain/detention-management/2011 (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Chiesa, V.; Chiarenza, A.; Mosca, D.; Rechel, B. Health records for migrants and refugees: A systematic review. Health Policy 2019, 123, 888–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization D of M Newborn. Standards for Improving the Quality of Care for Children and Young Adolescents in Health Facilities. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/mca-documents/child/standards-for-improving-the-quality-of-care-for-children-and-young-adolescents-in-health-facilities--policy-brief.pdf?sfvrsn=1e568644_1 (accessed on 21 May 2023).

- O’Donnell, H.C.; Suresh, S.; Council on Clinical Information Technology; Webber, E.C.; Alexander, G.M.; Chung, S.L.; Hamling, A.M.; Kirkendall, E.S.; Mann, A.M.; Sadeghian, R.; et al. Electronic Documentation in Pediatrics: The Rationale and Functionality Requirements. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20201682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusack, C.M.; Hripcsak, G.; Bloomrosen, M.; Rosenbloom, S.T.; Weaver, C.A.; Wright, A.; Vawdrey, D.K.; Walker, J.; Mamykina, L. The future state of clinical data capture and documentation: A report from AMIA’s 2011 Policy Meeting. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2013, 20, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, E.; Patel, N.; Chandrasekaran, K.; Tajik, A.J.; Paterick, T.E. The Importance of the Medical Record: A Critical Professional Responsibility. J. Med. Pract. Manag. MPM 2016, 31, 305–308. [Google Scholar]

- Tellez, D.; Tejkl, L.; McLaughlin, D.; Vallet, M.; Abrahim, O.; Spiegel, P.B. The United States detention system for migrants: Patterns of negligence and inconsistency. J. Migr. Health 2022, 6, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sridhar, S.; Digidiki, V.; Kunichoff, D.; Bhabha, J.; Sullivan, M.; Gartland, M. Child Migrants in Family Immigration Detention in the US: An Examination of Current Pediatric Care Standards and Practices; FXB Center for Health and Human Rights at Harvard University, Boston and MGH Asylum Clinic at the Center for Global Health: Boston, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap Consortium: Building an International Community of Software Platform Partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)—A Metadata-Driven Methodology and Workflow Process for Providing Translational Research Informatics Support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemec, S.F.; Bankier, A.A.; Eisenberg, R.L. Upper Lobe–Predominant Diseases of the Lung. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2013, 200, W222–W237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolt, D.; Starke, J.R. Tuberculosis Infection in Children and Adolescents: Testing and Treatment. Pediatrics 2021, 148, e2021054663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.J.; Teach, S.J. Asthma. Pediatr. Rev. 2019, 40, 549–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas-Moore, J.; Lewis, R.; Patrick, J. The importance of clinical documentation. Bull. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2014, 96, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnapper, M.; Mandelberg, A.; Witzling, M.; Sion Sarid, R.; Dalal, I.; Armoni Domany, K. The Wandering Calcified Lung Nodule. J. Pediatr. 2021, 231, 293–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- New Jersey Medical School Global Tuberculosis Institue. Management of Latent Tuberculosis Infection in Children and Adolescents: A Guide for the Primary Care Provide. 2009. p. 5. Available online: https://globaltb.njms.rutgers.edu/downloads/products/PediatricGuidelines%20(Screen).pdf (accessed on 21 May 2023).

- Martorell, R. Improved nutrition in the first 1000 days and adult human capital and health. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2017, 29, e22952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walson, J.L.; Berkley, J.A. The impact of malnutrition on childhood infections. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 31, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansuya; Nayak, B.S.; Unnikrishnan, B.; Shashidhara, Y.N.; Mundkur, S.C. Effect of nutrition intervention on cognitive development among malnourished preschool children: Randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, N.C.; Nyathi, S.; Chapman, L.A.C.; Rodriguez-Barraquer, I.; Kushel, M.; Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Lewnard, J.A. Influenza, Varicella, and Mumps Outbreaks in US Migrant Detention Centers. JAMA 2020, 325, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC TB Risk and People Who Live or Work in Correctional Facilities. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/risk-factors/correctional-facilities.html (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Hampton, K.; Mishori, R.; Griffin, M.; Hillier, C.; Pirrotta, E.; Wang, N.E. Clinicians’ perceptions of the health status of formerly detained immigrants. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podder, V.; Lew, V.; Ghassemzadeh, S. SOAP Notes. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Family Residential Standards 2020 | ICE. Available online: https://www.ice.gov/detain/detention-management/family-residential (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Ebbers, T.; Kool, R.B.; Smeele, L.E.; Dirven, R.; Den Besten, C.A.; Karssemakers, L.H.E.; Verhoeven, T.; Herruer, J.M.; Van Den Broek, G.B.; Takes, R.P. The Impact of Structured and Standardized Documentation on Documentation Quality; a Multicenter, Retrospective Study. J. Med. Syst. 2022, 46, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Immigrant Justice Center. ICE Released Its Most Comprehensive Immigration Detention Data Yet. It’s Alarming. Available online: https://immigrantjustice.org/staff/blog/ice-released-its-most-comprehensive-immigration-detention-data-yet (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- American Immigration Council. Oversight of Immigration Detention: An Overview. 2022. Available online: https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/oversight-immigration-detention-overview (accessed on 13 February 2024).

- Melhado, W. 8-Year-Old Girl Dies While in Federal Custody on the Border. Available online: https://www.texastribune.org/2023/05/17/child-death-border-custody/ (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Miroff, N. After Latest Child’s Death, Care at U.S. Border Facilities under Review. Washington Post. 25 May 2023. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/immigration/2023/05/22/child-death-border-migrants/ (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- AP News. He Wanted to Live the American Dream: Honduran Teen Dies in US Immigration Custody. Available online: https://apnews.com/article/migrant-child-death-border-hhs-honduras-0f23efb966adb7a64d7a72640e320d17 (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Cuffari, J. Many Factors Hinder ICE’s Ability to Maintain Adequate Medical Staffing at Detention Facilities. Office of Inspector General Department of Homeland Security. 2021. Available online: https://www.oig.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/assets/2021-11/OIG-22-03-Oct21.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2023).

- Report of the ICE Advisory Committee on Family Residential Centers. 2016. Available online: https://www.ice.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Report/2016/acfrc-report-final-102016.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2023).

- Saadi, A.; Tesema, L. Privatisation of immigration detention facilities. Lancet 2019, 393, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Age at Arrival Grouping (Years) | N (%) |

|---|---|

| <2 | 16/165 (9.7%) |

| 2–5 | 34/165 (20.6%) |

| 6–9 | 36/165 (21.8%) |

| 10–17 | 79/165 (47.9%) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 15/163 (9.2%) |

| Male | 148/163 (90.8%) |

| Region | |

| Africa | 4/163 (2.5%) |

| Asia | 1/163 (0.6%) |

| Europe | 3/163 (1.8%) |

| Northern Triangle (El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras) | 92/163 (56.4%) |

| Remainder Central America/Carribean | 43/163 (26.4%) |

| South America | 20/163 (12.3%) |

| Languages spoken | |

| Spanish | 122/165 (73.9%) |

| Creole | 20/165 (12.1%) |

| Indigenous Lang. of Guatemala | 7/165 (4.2%) |

| Portuguese | 7/165 (4.2%) |

| French/Lingala | 2/165 (1.2%) |

| Romanian | 2/165 (1.2%) |

| Mandarin | 1/165 (0.6%) |

| Russian | 1/165 (0.6%) |

| Not specified | 3/165 (1.8%) |

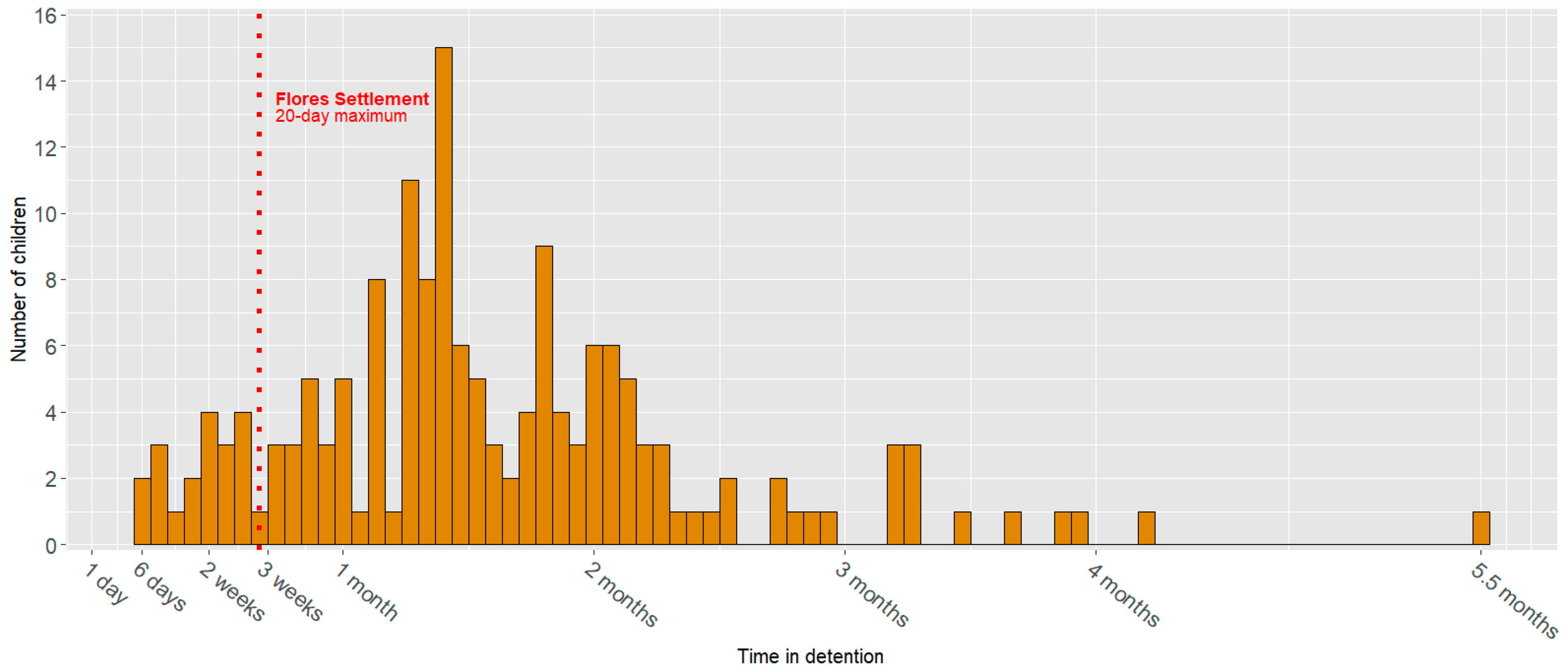

| Days in detention | |

| 0–20 days | 20/164 (12.2%) |

| 21–89 days | 132/164 (80.5%) |

| +90 days | 13/164 (7.9%) |

| Nutritional Condition | Categories | Z-Score Ranges | Full Sample (N = 165) | 0–4 Years Old (N = 42) | 5–18 Years Old (N = 123) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malnourishment (WFH for 0–4 yo, BFA for 5+ yo) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Any level of malnourishment | ≤−2 | 7/163 (4.3%) | 3/42 (7.1%) | 4/121 (3.3%) | |

| Severe | ≤−3 | 0/7 (0%) | 0/3 (0%) | 0/4 (0%) | |

| Moderate | ≤−2 & ≥−3 | 7/7 (100%) | 3/3 (100%) | 4/4 (100%) | |

| No malnourishment | >−2 | 156/163 (95.7%) | 39/42 (92.9%) | 117/121 (96.7%) | |

| At risk | ≤−1 & >−2 | 19/156 (12.2%) | 7/39 (17.9%) | 12/117 (10.3%) | |

| Stunting (HFA) | |||||

| Any level of stunting | ≤−2 | 37/163 (22.7%) | 5/42 (11.9%) | 32/121 (26.4%) | |

| Severe | ≤−3 | 9/37 (24.3%) | 0/5 (0%) | 23/32 (71.9%) | |

| Moderate | ≤−2 & ≥−3 | 28/37 (7.6%) | 5/5 (100%) | 9/32 (28.1%) | |

| No stunting | >−2 | 126/163 (77.3%) | 37/42 (88.1%) | 89/121 (73.6%) | |

| At risk | ≤−1 & >−2 | 35/126 (27.8%) | 6/37 (16.2%) | 29/89 (32.6%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sridhar, S.; Digidiki, V.; Ratner, L.; Kunichoff, D.; Gartland, M.G. Child Migrants in Family Detention in the US: Addressing Fragmented Care. Children 2024, 11, 944. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11080944

Sridhar S, Digidiki V, Ratner L, Kunichoff D, Gartland MG. Child Migrants in Family Detention in the US: Addressing Fragmented Care. Children. 2024; 11(8):944. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11080944

Chicago/Turabian StyleSridhar, Shela, Vasileia Digidiki, Leah Ratner, Dennis Kunichoff, and Matthew G. Gartland. 2024. "Child Migrants in Family Detention in the US: Addressing Fragmented Care" Children 11, no. 8: 944. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11080944

APA StyleSridhar, S., Digidiki, V., Ratner, L., Kunichoff, D., & Gartland, M. G. (2024). Child Migrants in Family Detention in the US: Addressing Fragmented Care. Children, 11(8), 944. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11080944