“Mimics” of Injuries from Child Abuse: Case Series and Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

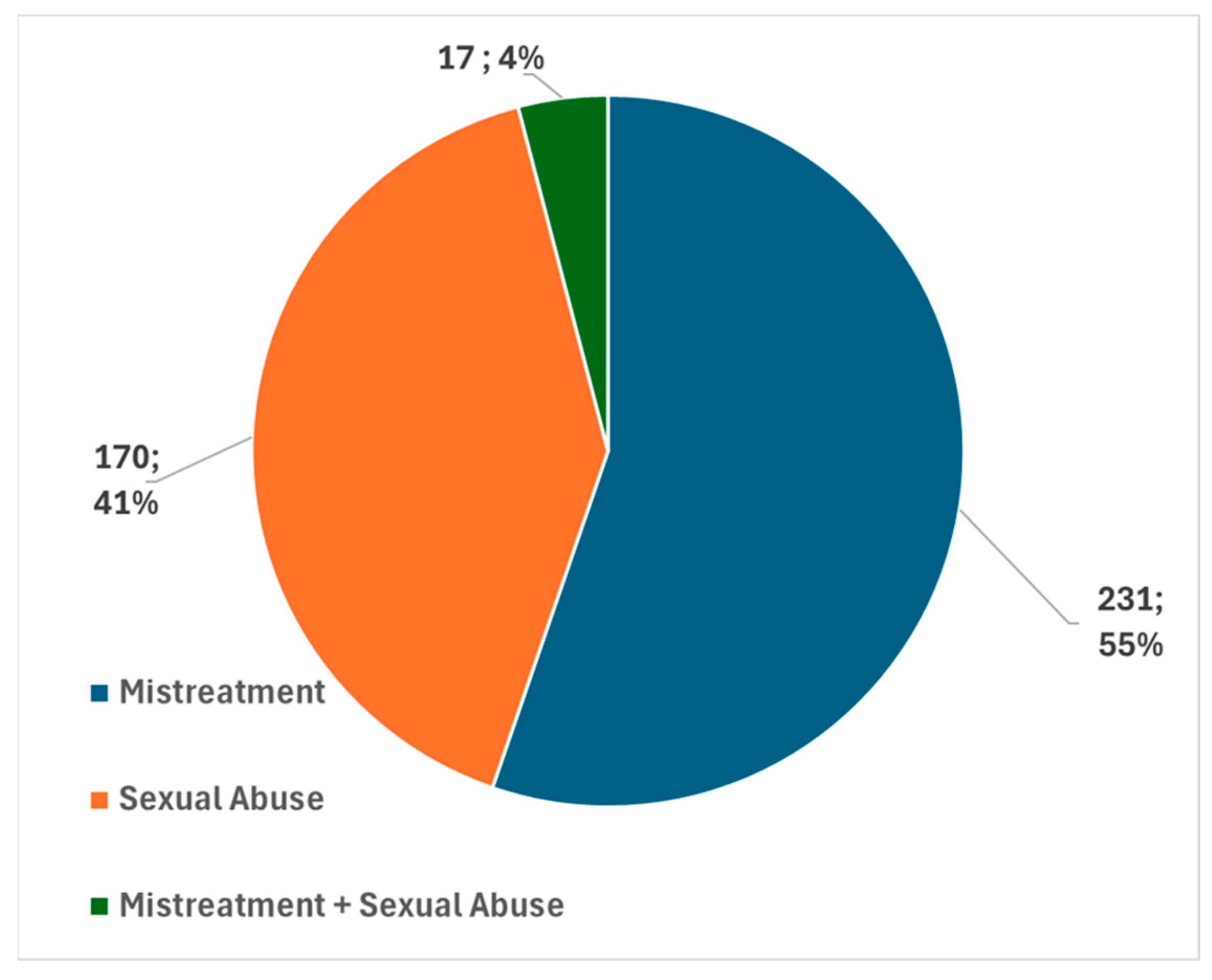

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brown, C.L.; Yilanli, M.; Rabbitt, A.L. Child Physical Abuse and Neglect. 2023. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Viero, A.; Amadasi, A.; Blandino, A.; Kustermann, A.; Montisci, M.; Cattaneo, C. Skin lesions and traditional folk practices: A medico-legal perspective. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2019, 15, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirtschig, G. Lichen Sclerosus-Presentation, Diagnosis and Management. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2016, 113, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Özer, H.; Abakli İnci, M. Knowledge and experience of pediatricians and pedodontists in identifying and managing child abuse and neglect cases. Medicine 2024, 103, e37548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, B.; Butterfield, R. Common skin and bleeding disorders that can potentially masquerade as child abuse. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 2015, 169, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, K.; Metz, J.; Feldman, K.; Sidbury, R.; Lindberg, D. Cutaneous findings mistaken for physical abuse: Present but not pervasive. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2014, 31, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentivegna, K.; Grant-Kels, J.M.; Livingston, N. Cutaneous mimics of child abuse and neglect: Part II. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2022, 87, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, J.B.; Schwartz, K.A.; Feldman, K.W.; Lindberg, D.M.; ExSTRA Investigators. Non-cutaneous conditions clinicians might mistake for abuse. Arch. Dis. Child. 2014, 99, 817–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killion, C.M. Cultural Healing Practices that Mimic Child Abuse. Ann. Forensic Res. Anal. 2017, 4, 1042. [Google Scholar]

- Lupariello, F.; Coppo, E.; Cavecchia, I.; Bosco, C.; Bonaccurso, L.; Urbino, A.; Di Vella, G. Differential diagnosis between physical maltreatment and cupping practices in a suspected child abuse case. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2020, 16, 188–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, T.S. Bruises in children: Normal or child abuse? J. Pediatr. Health Care 2010, 24, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudd, S.S.; Findlay, J.S. The cutaneous manifestations and common mimickers of physical child abuse. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2004, 18, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashi, N.A.; Patzelt, N.; Wirya, S.; Maymone, M.B.C.; Zancanaro, P.; Kundu, R.V. Dermatoses caused by cultural practices: Therapeutic cultural practices. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018, 79, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.E.; Lee, S.S.; Lee, M.S.; Choi, S.M.; Ernst, E. Adverse events of moxibustion: A systematic review. Complement. Ther. Med. 2010, 18, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faller-Marquardt, M.; Pollak, S.; Schmidt, U. Cigarette burns in forensic medicine. Forensic Sci. Int. 2008, 176, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marion, T.; Cao, K.; Roman, J. Gua Sha, or Coining Therapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2018, 154, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlJasser, M.; Al-Khenaizan, S. Cutaneous mimickers of child abuse: A primer for pediatricians. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2008, 167, 1221–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abder-Rahman, H.; Habash, I.; Hussein, A.; Al-Shaeb, A.; Elqasass, A.; Qaqish, L.N. Genital lichen sclerosus misdiagnosis: Forensic insights. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, C.W.; States, L.J. Medical Mimics of Child Abuse. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2017, 208, 982–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettner, M.; Birngruber, C.G.; Niess, C.; Baz-Bartels, M.; Bunzel, L.; Verhoff, M.A.; Lux, C.; Ramsthaler, F. Mongolian spots as a finding in forensic examinations of possible child abuse-implications for case work. Int. J. Legal. Med. 2020, 134, 1141–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbe, V.; Boy, D.; Büttner, A. Mongolian Spots—A challenging clinical sign. Forensic Sci. Int. 2021, 327, 110964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greig, A.V.; Harris, D.L. A study of perceptions of facial hemangiomas in professionals involved in child abuse surveillance. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2003, 20, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, A.; Selbst, S. Vulvar hemangioma simulating child abuse. Clin. Pediatr. 1988, 27, 213–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.; Carpenter, S.L.; Anderst, J.D. Challenges in the evaluation for possible abuse: Presentations of congenital bleeding disorders in childhood. Child Abus. Negl. 2012, 36, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadjem, H.; Sutor, A.H. Hematoma in acute leukemia--suspected diagnosis of child abuse. Beitr. Zur Gerichtl. Med. 1991, 49, 227–231. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, S.L.; Abshire, T.C.; Anderst, J.D. Section on Hematology/Oncology and the Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect. Evaluating for suspected child abuse: Conditions that predispose to bleeding. Pediatrics 2013, 131, e1357–e1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepin, M.G.; Byers, P.H. What every clinical geneticist should know about testing for osteogenesis imperfecta in suspected child abuse cases. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 2015, 169, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abtahi-Naeini, B.; Shapouri, J.; Masjedi, M.; Saffaei, A.; Pourazizi, M. Unexplained facial scar: Child abuse or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome? N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2014, 6, 595–598. [Google Scholar]

- Castori, M. Ehlers–Danlos syndrome(s) mimicking child abuse: Is there an impact on clinical practice? Am. J. Med. Genet. Part C Semin. Med. Genet. 2015, 169, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupariello, F. Child abuse and traditional medicine practices. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2020, 16, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sex | Age | Country of Origin | Injuries Description | Suspected | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

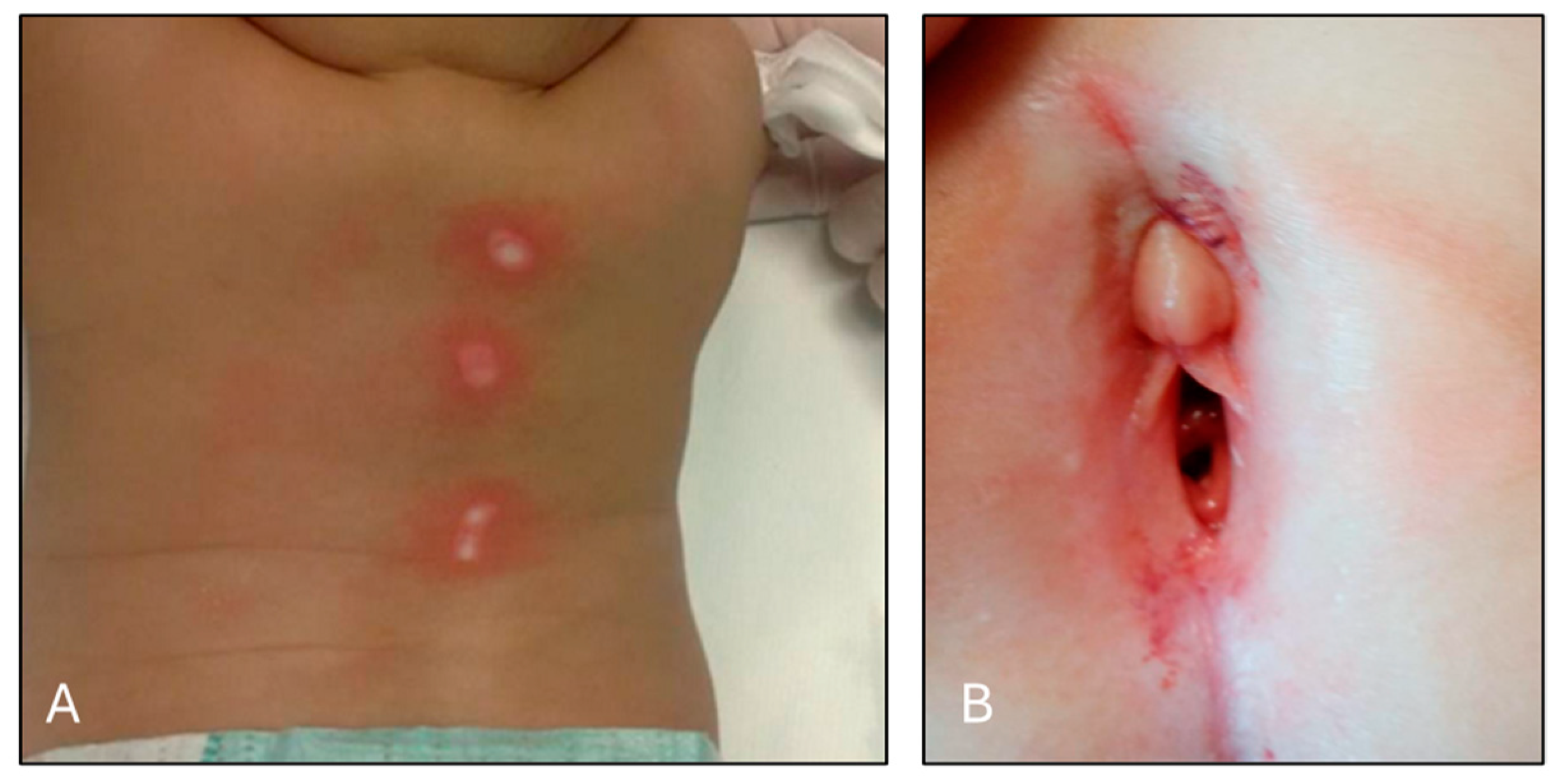

| F | 8 months | China | Burns on the back (Figure 2A) | Mistreatment | Cupping |

| M | 3 years | Ghana | Abrasions and continuous solutions | Mistreatment | Alternative Therapeutic practice |

| M | 6 years | Senegal | Ecchymosis on the back | Mistreatment | Cupping |

| F | 4 years | Italy | Perigenital ecchymosis with blood loss (Figure 2B) | Sexual Abuse | Genital Lichen Sclerosus et Atrophicus |

| F | 8 years | Italy | Perigenital ecchymosis and blisters | Sexual Abuse | Genital Lichen Sclerosus et Atrophicus |

| F | 10 years | Albania | Genital abrasions with bleeding | Sexual Abuse | Genital Lichen Sclerosus et Atrophicus |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Focardi, M.; Gori, V.; Romanelli, M.; Santori, F.; Bianchi, I.; Rensi, R.; Defraia, B.; Grifoni, R.; Gualco, B.; Nanni, L.; et al. “Mimics” of Injuries from Child Abuse: Case Series and Review of the Literature. Children 2024, 11, 1103. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11091103

Focardi M, Gori V, Romanelli M, Santori F, Bianchi I, Rensi R, Defraia B, Grifoni R, Gualco B, Nanni L, et al. “Mimics” of Injuries from Child Abuse: Case Series and Review of the Literature. Children. 2024; 11(9):1103. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11091103

Chicago/Turabian StyleFocardi, Martina, Valentina Gori, Marta Romanelli, Francesco Santori, Ilenia Bianchi, Regina Rensi, Beatrice Defraia, Rossella Grifoni, Barbara Gualco, Laura Nanni, and et al. 2024. "“Mimics” of Injuries from Child Abuse: Case Series and Review of the Literature" Children 11, no. 9: 1103. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11091103

APA StyleFocardi, M., Gori, V., Romanelli, M., Santori, F., Bianchi, I., Rensi, R., Defraia, B., Grifoni, R., Gualco, B., Nanni, L., & Losi, S. (2024). “Mimics” of Injuries from Child Abuse: Case Series and Review of the Literature. Children, 11(9), 1103. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11091103