Making Sense of Missense: Assessing and Incorporating the Functional Impact of Constitutional Genetic Testing

Highlights

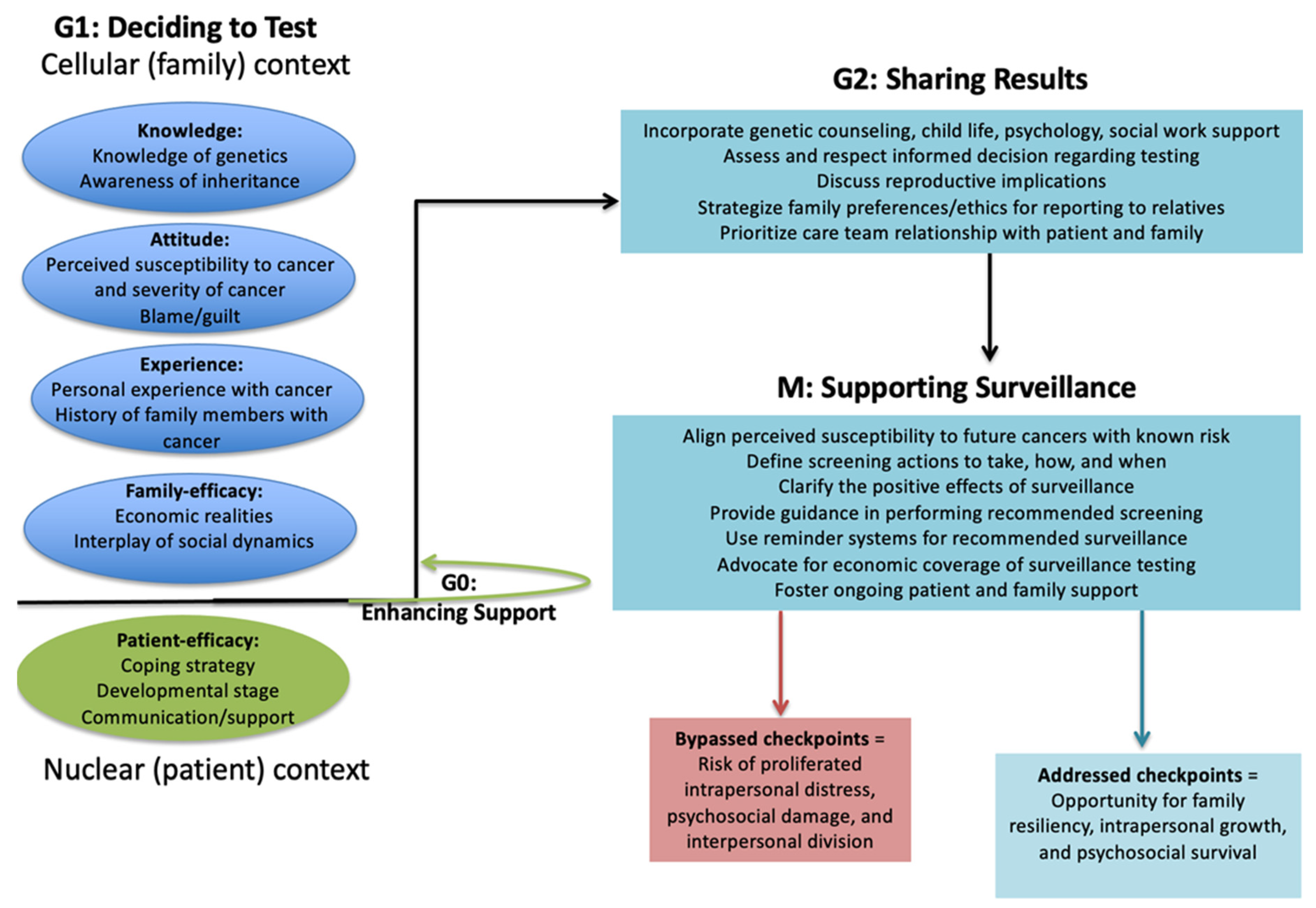

- Assessing families for cancer predisposition syndromes is an increasingly common practice in pediatric oncology.

- Testing for cancer-predisposition syndromes in pediatric oncology enables cancer surveillance, helps tailor and inform cancer-directed treatments, and may assist in family risk assessment.

- Receiving a diagnosis of a cancer predisposition syndrome can be a complex experience with practical, existential, and psychosocial implications for patients and their families.

- Consideration should be given to each family’s experience in receiving a cancer predisposition diagnosis, for both their immediate processing of the diagnosis and subsequent need for longitudinal support.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| G0–G2 | Gap0, Gap1, and Gap2 are the cellular growth phases |

| LFS | Li–Fraumani syndrome |

| M | Metaphase |

| TP53 | Tumor protein 53 gene |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Quality Tactics Specific to Research Design

| Quality Measure | Research Tactic Used | Applied | Timing of Tactic |

| Construct validity |

|

|

|

| Internal validity |

|

|

|

| External validity |

|

|

|

| Reliability |

|

|

|

| Table revised with permission from Yin, R.K. Research: Design and Methods, 5th edition (SAGE Publications, Inc., 2013), page 45 [15]. | |||

Appendix A.2. Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ)

| Domain 1. Research team and reflexivity | |

| Personal characteristics | |

| 1. Interviewer/facilitator | MW conducted the interviews |

| 2. Credentials | The study team consisted of doctoral-level investigators from the field of pediatric oncology, genetics, and psychology |

| 3. Occupation | Members of the study team included oncologists, a geneticist, a laboratory investigator, and a pediatric psychologist |

| 4. Gender | The research team consisted of a balance of gender representation |

| 5. Experience and training of interviewer | The interviewer has completed cognitive interview graduate-level training from sociology/anthropology investigators, has completed qualitative software coursework with tutelage from an Atlas.ti software designer, completed graduate-level qualitative methodology coursework prior to study design and interview implementation, and receives ongoing mentoring from qualitative investigators |

| Relationship with participants | |

| 6. Relationship established | The study was mentioned to the family by their psychologist and oncologist two weeks prior to interviews with an in-person introduction to interviewer occurring one day prior to interviews |

| 7. Participant knowledge of interviewer | The participants were made aware that the interviewer is interested in decision-making constructs and that the study team was interested in learning about the family’s experiences to gain insight about impacts of genetic testing |

| 8. Interviewer characteristics | The interviewer utilizes positive affirmation during interviews (nodding and sharing verbal agreement) with follow-up questions (while avoiding leading) and tolerates extended silence during interviews to foster open, engaged conversations |

| Domain 2. Study design | |

| Theoretical framework | |

| 9. Methodological orientation and theory | Qualitative study methodology underpinned the study; inductive reasoning (grounded theory) was applied for data analysis |

| Participant selection | |

| 10. Sampling | The participants were selected due to complexity of medical history and recognized importance of learning from their health experiences (purposive sampling approach) |

| 11. Method of approach | Participants were approached face-to-face by interviewer |

| 12. Sample size | n = 2 individuals, n = 1 family unit |

| 13. Non-participation | Two invited participants elected to participate after an engaged process of informed consent |

| Setting | |

| 14. Setting of data collection | Data were collected in clinic conference room setting, which is a comfortable room with sofa chairs (non-medical environment) |

| 15. Presence of non-participants | No one else was present during interviews besides the participants and researchers; the participants were given the option of including non-participants or their psychologist in the room for support |

| 16. Description of sample | Demographics and data are deliberately omitted to protect the privacy/confidentiality of participants |

| Data collection | |

| 17. Interview guide | The questions were reviewed by a genetic-psychologist expert from a different institution, two genetic counselors, and two qualitative research teams piloted on an adult cancer patient diagnosed with a BRCA1 mutation |

| 18. Repeat interviews | Repeat interviews were carried out, as per the triangulated format described in methodology |

| 19. Recording | Interviews were voice recorded |

| 20. Field notes | Field notes were not made during the interviews, but, the interview engaged in memoing immediately after the interviews to reflect upon interview setting/content |

| 21. Duration | The interviews each lasted just under one hour |

| 22. Data saturation | Saturation was not an a priori goal; any and all raised themes were included as relevant |

| 23. Transcripts returned | Transcripts were returned to the participants for comments and for opportunity for correction |

| Domain 3. Analysis and findings | |

| 24. Number of data coders | Two data coders coded the data |

| 25. Description of coding tree | Coding tree provided as table within manuscript |

| 26. Derivation of themes | Themes were identified from the data as social constructs and two data coders then converted the social constructs into genetic terminology |

| 27. Software | NVivo was used to manage the data |

| 28. Participant checking | Participants provided feedback on findings |

| Reporting | |

| 29. Quotations presented | Participant quotations were presented to illustrate themes. To protect participant privacy, quotation was not identified by participant name. |

| 30. Data and findings consistent | The data presented were consistent with evidence base gathered through literature search completed prior to interview initiation |

| 31. Clarity of major themes | Major themes were clearly presented in the form of text summary |

| 32. Clarity of minor themes | Minor themes were described by list format in the manuscript figure |

| Adapted with permission from Tong, A., Sainsbury, P. & Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 19, 349–357 (2007) [19]. | |

Appendix A.3. Interview Script for LiSTENING Study Protocol

References

- Junttila, M.R.; Evan, G.I. p53—A Jack of all trades but master of none. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, P.A.; Vousden, K.H. p53 mutations in cancer. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, A.; Tabori, U.; Schiffman, J.; Shlien, A.; Beyene, J.; Druker, H.; Novokmet, A.; Finlay, J.; Malkin, D. Biochemical and imaging surveillance in germline TP53 mutation carriers with Li-Fraumeni syndrome: A prospective observational study. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custodio, G.; Parise, G.A.; Kiesel Filho, N.; Komechen, H.; Sabbaga, C.C.; Rosati, R.; Grisa, L.; Parise, I.Z.; Pianovski, M.A.; Fiori, C.M.; et al. Impact of neonatal screening and surveillance for the TP53 R337H mutation on early detection of childhood adrenocortical tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 2619–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meiser, B. Psychological impact of genetic testing for cancer susceptibility: An update of the literature. Psychooncology 2005, 14, 1060–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopie, J.P.; Vasen, H.F.; Tibben, A. Surveillance for hereditary cancer: Does the benefit outweigh the psychological burden?—A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 2012, 83, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overby, C.L.; Tarczy-Hornoch, P. Personalized medicine: Challenges and opportunities for translational bioinformatics. Pers. Med. 2013, 10, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lammens, C.R.; Aaronson, N.K.; Wagner, A.; Sijmons, R.H.; Ausems, M.G.; Vriends, A.H.; Ruijs, M.W.; van Os, T.A.; Spruijt, L.; Gomez Garcia, E.B.; et al. Genetic testing in Li-Fraumeni syndrome: Uptake and psychosocial consequences. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 3008–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, S.K.; Pentz, R.D.; Marani, S.K.; Ward, P.A.; Blanco, A.M.; LaRue, D.; Vogel, K.; Solomon, T.; Strong, L.C. Psychological functioning in persons considering genetic counseling and testing for Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Psychooncology 2008, 17, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleiker, E.M.; Hahn, D.E.; Aaronson, N.K. Psychosocial issues in cancer genetics—Current status and future directions. Acta Oncol. 2003, 42, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, P.L.; Malkin, D.; Garber, J.E.; Schiffman, J.D.; Weitzel, J.N.; Strong, L.C.; Wyss, O.; Locke, L.; Means, V.; Achatz, M.I.; et al. Li-Fraumeni syndrome: Report of a clinical research workshop and creation of a research consortium. Cancer Genet. 2012, 205, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.P.; Garber, J.E.; Friend, S.H.; Strong, L.C.; Patenaude, A.F.; Juengst, E.T.; Reilly, P.R.; Correa, P.; Fraumeni, J.F., Jr. Recommendations on predictive testing for germ line p53 mutations among cancer-prone individuals. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1992, 84, 1156–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lammens, C.R.; Bleiker, E.M.; Aaronson, N.K.; Wagner, A.; Sijmons, R.H.; Ausems, M.G.; Vriends, A.H.; Ruijs, M.W.; van Os, T.A.; Spruijt, L.; et al. Regular surveillance for Li-Fraumeni Syndrome: Advice, adherence and perceived benefits. Fam. Cancer 2010, 9, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michie, S.; Bobrow, M.; Marteau, T.M. Predictive genetic testing in children and adults: A study of emotional impact. J. Med. Genet. 2001, 38, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ceswell, J. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design (Choosing Among Five Traditions), 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ayres, L.; Kavanaugh, K.; Knafl, K.A. Within-case and across-case approaches to qualitative data analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2003, 13, 871–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pope, C.; Mays, N. Reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: An introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. BMJ 1995, 311, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pope, C.; Ziebland, S.; Mays, N. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ 2000, 320, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petitjean, A.; Achatz, M.I.; Borresen-Dale, A.L.; Hainaut, P.; Olivier, M. TP53 mutations in human cancers: Functional selection and impact on cancer prognosis and outcomes. Oncogene 2007, 26, 2157–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Genetic Principle | Psychosocial Construct | Exemplifying Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Missense Point mutation with impact on function | Poignant moment of receiving positive constitutional genetic test results, subsequently trying to “make sense” of life in context of cancer predisposition. | “Well, I don’t remember too much about that actual day of hearing the genetic results. Maybe I choose not to.” “It was upsetting … it was devastating to the whole family when you hear something like this [genetic diagnosis]” |

| Checkpoint activation Protective monitoring of cell progression through sequential events | Process of care team confirming patient and family preparation prior to sequential testing events: deciding to undergo diagnostic test (G1), receiving test result (G2), initiating surveillance testing (M). | G1—“She [genetics counselor] was, in a way, kind of persuading us not to do genetic testing because she said, “Well, most people don’t want to know.” I think that is her job, you know, making sure families are prepared and ready for the news, of course. I know they [children] are very young, but our family needs to know. We have a right to know. It is important for our health to know.” G2—“If something else was to go wrong with someone in our family, that now we can look closer because of the genetic importance … it’s important … we needed to get information from the test result. They prepared us to get results.” M—“Although, the extra testing is both the easiest part and the hardest part. Like, I mean, they need to come here and get some more scans and things that we weren’t going to be doing before. I will need to do that too, for my health. And, from my point of view, a hard part is paying the doctor or hospital for testing and imaging and stuff that you normally wouldn’t be spending money or insurance bills on since now from the genetics you are going to have these test done. But, the easiest part would be that maybe you could find a different cancer sooner and start treatment earlier.” |

| Frameshift insertion Altered reading of codons due to new insertion | Impact on a person’s interpretation of family medical history due to new frame of reference (input of genetics knowledge altering translation of events). | “When I was in my early twenties, my father had a brain tumor and he saw a specialist, of course. After they had removed some of the brain tumor, they did some testing, and they said that they thought that it might be a genetic possibility for the fact of how large the brain tumor was and the location. But he never actually got tested, even though, well, he also had leukemia later. So I was always, in the back of my mind, was always wondering, ‘what is this?’” “I asked about osteosarcoma and whether it could be genetic way back years ago, when he had his first cancer, and we came for his first treatment. I asked about genetics way back then … and they told me no. They told me it was just something that happened. So, you know, maybe at that time if genetics was brought up then we would have thought about it more and done genetic testing back then. Maybe, maybe we would have known about our family genes sooner. Maybe knowing about the genetics back then would have helped us find and diagnose this second cancer sooner.” |

| Modifier Effectual influence on the expression of another gene | Recognition that the way one family member processes and responds to a genetic diagnosis may influence psychosocial experience of another family member. | “I agree with what she [mom] says … what she says influences how I feel and think about the genetics.” |

| Alternative Splicing Single gene coding for multiple proteins with differences in sequence and function | Acknowledgement of the unique personality of each family member, warranting personalized approach to timing and content of communication about genetic testing (single message, multiple interpretations). | “He’s quite mature on a lot of the medical things being the fact that everything he’s gone through at such an early age. So, he needed different words in the genetic talks.” “For her, it’s different, because she’s still very young and she wants children, but it’s also very confusing. And she, as a sister, has to see this, so she’s kind of a little conflicted. Whether to even think of having her own children and not getting the whole scope or thinking the whole scope of everything. We have to talk to her in that unique way of thinking further down the line and her future.” “They have different needs. They need to hear things differently. And, they both think differently.” |

| Alternate promoters Privileged region of transcription initiation | Recognition that certain care team members or family members may be better positioned than others to initiate essential tasks such as deciding to undergo testing or result sharing. | “For them [certain relatives], of course, there was no problem explaining the genetic news to them. And then, of course, with them it’s a very real possibility that they have it too and so I felt an obligation to tell. I told.” “So I thought and thought and whether to tell them [certain distant relatives] about the cancer gene. It was very hard to just make a decision if I should contact them and tell them this or not. After much thinking, I decided since I don’t have a very close relationship with them, that I didn’t have a role to tell them. And I had left it with my grandfather and decided that he was closer to them than I was and that if he wanted to make the decision to tell them, he could. And I left it that way. I think that was best because he knows them and their personal needs to know or not to know.” |

| Gain of function Neomorphic mutation, resulting in gene product with increased function | Gain of insight or perceived benefit from receipt of genetic diagnosis; a dominant theme. | “You get lumps or bumps or moles or little things and you just think, “oh, it’s no big deal.” And it really could be something. So, you know, try to find out [genetic results] as soon as possible, it’s a better option, I think, when trying to get treatment you can get it earlier and protect yourself.” “Personally, I would want to know if there’s something wrong and what I can do to prevent it or to find out sooner just in order to be able to live a healthy, happy life with my children. So, to me … it’s just like going to the dentist and finding out you have a cavity. You need to get it filled now, or you wait and then you need a root canal. But, the best thing is to find out about genetics early so you can help your family.” |

| Loss of function Amorphic mutation, resulting in gene product with less function | Concern about loss of personal or family function due to genetic test result; a recessive theme. | “Well, if you think about it, a cancer could happen anytime, anytime. A cancer could happen just out of nowhere. Cancer could happen again to you, or the cancer could happen to someone you love. Cancer could come again to your family because of the genes.” “These are hard life decisions, and I am having to think about these choice earlier than most people. Well, everyone has to make that very important life choice. That choice is if you want to still have kids or just stop even thinking about it and don’t have kids at all. I will have to think about genes when I think about that choice.” |

| Growth arrest Cessation of progression in cell cycle | Feelings of guilt, harm, stress, or stagnation due to damaging interactions or shock of familial cancer predisposition. | “But then, knowing that he’s gone through all this, as a mother’s point, you kind of feel like you might not want to have even ever had children because you don’t want them to suffer through this.” “When my dad was sick, the thought “maybe that is also in my DNA” had not occurred to me yet. Of course, by the time we actually knew there was something really, really wrong in our family health history, I was already pregnant with my daughter. But, I mean, if I knew then what I know now, I probably wouldn’t have had children. I would have thought not to have children, I mean, to save him from all of this very hard journey. I watch him. It’s hard.” |

| Senescence Cessation in division | Finding strength in family unity and comfort in togetherness; resistance to separation. | “I have a sister, and I try to talk to hear about it since we both have it … it’s something we share.” “We should hear all news together. I want for us to be together. We can face this better when we are together.” |

| Transactivation activities Increased rate of gene expression | Increasing expression of strength in knowledge. | “Personally, for me, I think I wanted to know [genetic predisposition] for my future, for my health, and for my well-being.” “Knowing is important for our daughter’s health, too. I know, little things, to take her to the doctor and be more aggressive with the doctor. As in, you know, for my son, it took two or three times for his first diagnosis. And his second diagnosis, I took him I don’t know how many times to our family doctor, ‘something’s wrong.’ But now, I would be adamantly like, ‘no, I know there is something wrong and these are the possibilities.’ If that makes sense. Knowing about the genes make me feel like I have an obligation to seek care and to get medical answers.” |

| Repair Cell identification of potential damage with corrective mechanisms | Fixing misinformation, mending misinterpretations, and providing new information through science | “Of course, my daughter wasn’t sure exactly what all the genetics language meant and she made the comment, ‘does that mean I have cancer?’ right away when they told her about the positive genetic test. Because, you know … she didn’t really understand the whole logic of the genetics, of course. I knew right away, and I said, ‘No, that’s not what the genetics test meant. The cancer gene doesn’t mean you have cancer.’ And, of course, they [the doctors] are great, they assured her, ‘No, no. That’s not what that means. It just means that your DNA’s a little bit different.’ They explained in a way that she could understand that this was meant to help for them to monitor her closer, but, it doesn’t mean that she’s going to for sure have cancer. It just means that she might have an increased possibility of having cancer … more possibility than a person normally would be. So, that helped. My daughter had fears, and they used their words to clarify and calm her fears.” “It’s kind of a vague thing, it’s like they [medical community] don’t know much about it. I kind of really feel like there’s actually more people out there that have it. I mean, how many people wake up and say, “Gee, I want to get DNA tested to see if I have a cancer gene or a migraine gene?” You know? So I think that there’s a lot more people out there. It would help me to know there are more people with this mutation. Maybe more people getting tested could make it feel more normal for the people who do get tested.” |

| Silent mutation | Resistance to allowing the genetic result to impose guilt, to change personal functions, to negatively impact view cancer, to change family structure, or to harm lived experiences. | “It, really, for me, it’s not a … not a horrible burden. It’s the way you’re made, it was nothing that you did wrong or anything like that. I mean, you feel bad because you have passed it to somebody else, especially since they, my children, have gone through so very much and I haven’t. But, like I said, it’s nothing anybody did wrong.” “I don’t think or live like I’m a ticking time bomb.” “I don’t think of the cancer any different knowing that genes caused it. He’s still sick. We still have to have treatment. It’s cancer. There’s no difference if cancer is genetic or not genetic because the treatment is not different at this time.” “I’m not disappointed that we did the genetic testing. In fact, I’m happy that we did it. To me, it’s not any different than going to the doctor and having them do some lab work and saying, ‘you’re diabetic now.’ If that makes sense, it should be treated like any other medical test. Some medical tests are important … you know, a pregnancy test, for example. You’re pregnant, you’re not pregnant, but it’s always just a test. The test impacts the future. What you do with the test is what is important. But, the test itself is no different than any other medical test.” “You know that you might live just a perfect life and never have another cancer. Your family might never have a cancer. You can’t be scared just because of genes.” “Life goes on. It’s not the end of the world to find out [about LFS].” “You could have totally different types of cancer. But, you continue with your daily life. It’s not like your life has stopped because of a genetic diagnosis, I mean, ours hasn’t.” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Weaver, M. Making Sense of Missense: Assessing and Incorporating the Functional Impact of Constitutional Genetic Testing. Children 2025, 12, 1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111449

Weaver M. Making Sense of Missense: Assessing and Incorporating the Functional Impact of Constitutional Genetic Testing. Children. 2025; 12(11):1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111449

Chicago/Turabian StyleWeaver, Meaghann. 2025. "Making Sense of Missense: Assessing and Incorporating the Functional Impact of Constitutional Genetic Testing" Children 12, no. 11: 1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111449

APA StyleWeaver, M. (2025). Making Sense of Missense: Assessing and Incorporating the Functional Impact of Constitutional Genetic Testing. Children, 12(11), 1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111449