Can Wearable Cameras Be Used to Validate School-Aged Children’s Lifestyle Behaviours?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Settings

2.2. Description and Validation of the CHAT

2.3. Instrumentation and Procedures

2.4. Method Comparison Protocol

2.5. Instrumentation of Group Interviews

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Method Comparison

Interview Analysis

“I find the consent form and your study, which would appear to involve a camera randomly taking pictures, gross violation of privacy dressed up as something cool to be part of because it’s the newest (privacy invading) technology.”

“It’s obvious the consent form is there to get around any legal issues you could face for such pictures, but I would like to ask if you had permission from the police to take random pictures of school children at the weekend, in their bedrooms getting changed etc., with or without consent?”

“I have spoken to several other parents this morning, who all feel exactly the same, meaning they do not want you taking pictures of them randomly. Would you allow the children to give you a camera for the weekend to take random pictures of your life?”

“To gauge my activities.”(B10)

“I was excited to wear a camera, and yeah, that it could see what you were doing and how long you were spending in certain places of certain activities.”(B14)

“I dunno, I saw people doing it and I thought it would be like cool to do it.”(B12)

“It was fun using the camera.”(B10)

“I enjoyed it.”(G6)

“At the park I had a problem. The guy was asking me if the camera was videoing. I said it was just recording photographs. I told him it just took pictures and then walked away.”(B14)

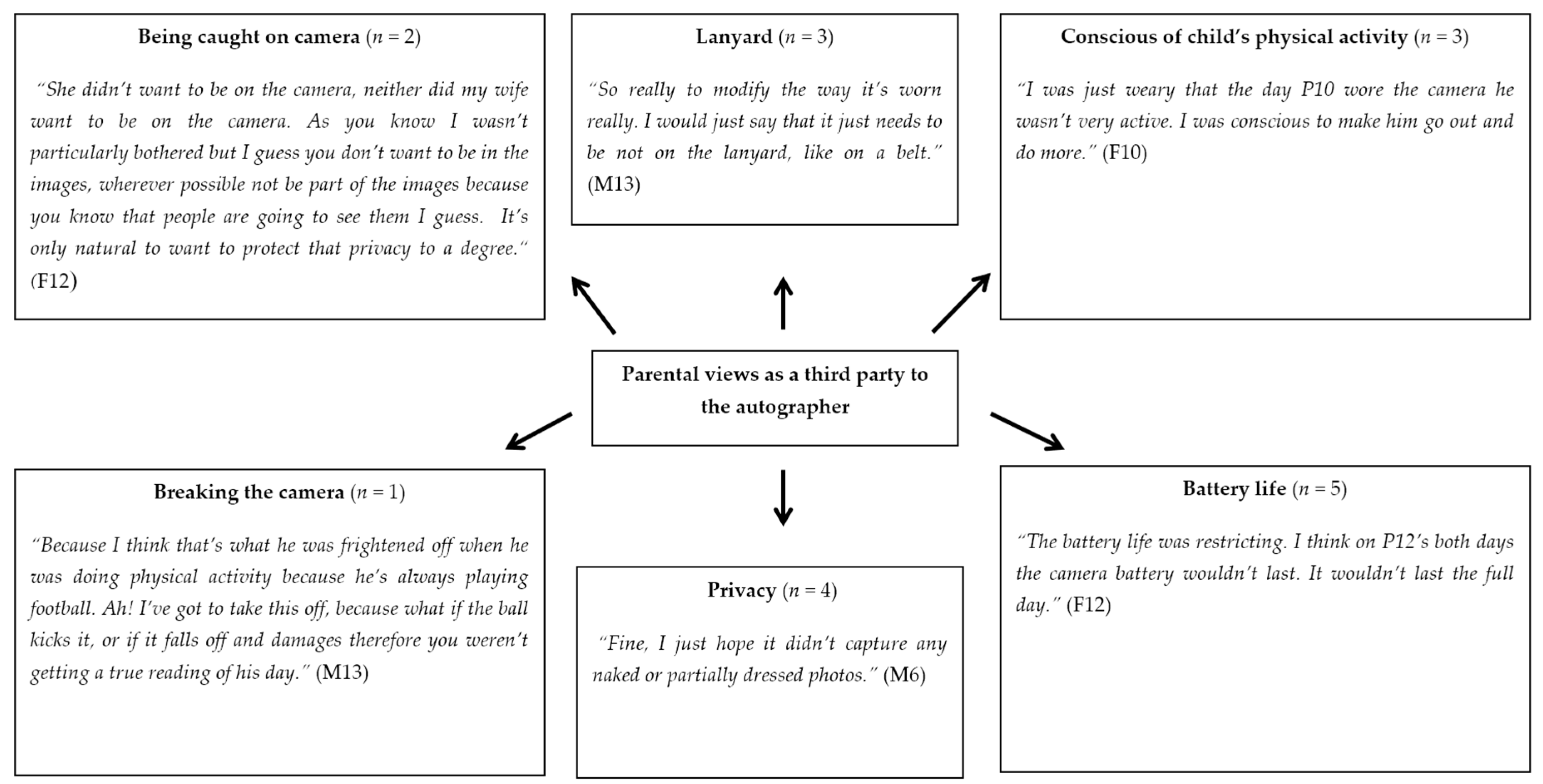

“My only concerns were the camera recording the sound and you hearing how much I shout. And then his younger brother being silly around the camera, I can’t remember which day but his younger brother getting his bum out.”(M11)

“The camera invades privacy. Dangerous when people are coming out of their showers in the morning, getting dressed, etc. In particular a problem as G5 gets dressed before the rest of us and her siblings. So, her older sister was mainly stressing, walking around in the morning without being caught by the camera. G5 did end up taking the camera off during the weekend day because she got angry with it, after she’d had an argument. We have younger children you see, so, members of our family did not want to be seen eating their dinner, etc., normal daily tasks were invaded. I found the camera caused lots of arguments due to people not wanting to be seen in their underwear or eating dinner. Not wanting to be photographed.”(M5)

“Improvement could have been made to the lanyard as it kept swinging around and would face the ceiling, face the wrong way. Then B12 would have perhaps felt more comfortable wearing it more for his activities throughout the day.”(F12)

“My husband would make B8 avoid him being filmed. So B8 would creep around the room trying to not get this dad in the shot.”(M8)

“You weren’t getting a true reading of his day. Whereas, he doesn’t necessarily do physical activity during the day, but there were parts where he was and they weren’t being recorded because he was too frightened to have it on in case it broke.”(M13)

“Easy and fun”(B2)

“It’s been interesting watching his day in a snapshot. You know, stuff that I don’t see you know as well in the playground. I think it’s been great. We are more aware of the amount of screen time.”(M11)

“I think it’s been positive, and I would recommend anybody to do it.”(M7)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Behaviour | CHAT Item | Criteria |

| Diet | How many portions of fruit and vegetables did you eat yesterday? | Agreement: If self-reported fruit and vegetable consumption aligns with those visually seen or if portion reported is 1 portion over or under estimation. Non-agreement: If none of self-reported portions are observed if all three or two meals are observed. Or if number of portions observed and recalled are more than 1 count difference, e.g., reported 5 when only observed eating 3 servings. Unable to align: If only one eating episode is observed then participant excluded. |

| Diet | What did you eat for breakfast? What did you have to eat for lunch? | Agreement: Can see participant eating/ preparing the meal that is self-reported. Non-agreement: If self-reported meal type does not match the observed breakfast or if report eating breakfast but it is not visually seen. Unable to align: If participant has not worn autographer during the given meal time. |

| Diet | What did you drink for breakfast? What did you have to drink for lunch? | Agreement: If a child self-reported drinking and this was observed in images. If the type of drink is identified, then this can be verified. Can clearly see the food being consumed is as the participant has self-reported. Non-agreement: If self-reported drink is not observed or vice versa, drink observed but not self-reported. Unable to align: If participant has not worn autographer for the morning or over the lunch time. |

| Physical activity | Before lessons started/after school how long did you spend doing sports or exercise? | Autographer Agreement: Self-report is within ±10 min of moderate physical activity derived from autographer annotations. Non-agreement: Self-report is greater than ±11 min of moderate physical activity derived from autographer annotations. Unable to align: If participant did not wear the autographer for greater than 30 min after school, they were excluded. Accelerometer Agreement: Self-reported duration is within ±10 min of time spent in MVPA. Non-agreement: Self-reported duration is greater than ±11 min of time spent in MVPA. Unable to align: If autographer was removed for >30 min after school. |

| Physical activity | How did you get to school yesterday morning? How did you get home yesterday? | Autographer Agreement: Self-report mode aligns with visual observation. Non-agreement: Self-report does not align with visual observation Unable to align: If autographer was not worn during the journey. |

| Acelerometer Agreement: Self-report mode aligns PA intensities engaged in during journey time derived from autographer images. Non-agreement: Self-report mode does not align with PA intensities engaged in during journey time derived from autographer images. Unable to align: If accelerometer was not worn during the journey. | ||

| Physical activity | Did you travel with an adult? | Agreement: Self-report aligns with visual observation during journey. Non-agreement: Self-report does not align with visual observation during journey. Unable to align: If devices were not worn during the journey. |

| Physical activity | What did you do for most of your morning break yesterday? Apart from eating your food, what did you do for most of your lunchtime yesterday? What did you do for most of your afternoon break yesterday? | Autographer Agreement: Self-report intensity aligns with the most time spent in particular behaviour (standing, walking or moderate). Non-agreement: Self-report does not align with the most time spent in particular behaviour (standing, walking or moderate). Unable to align: If participant did not wear the autographer at time segment. Accelerometer Agreement: Self-report intensity aligns with the most time spent in a particular behaviour (sedentary, light or MVPA). Non-agreement: Self-report mode does not align with the most time spent in a particular behaviour (sedentary, light or MVPA). Unable to align: If participant did not wear the accelerometer at time segment. |

| Lifestyle | Before lessons started/after school, how long did you spend watching TV, playing computer games, using iPad or internet? | Agreement: Self-report is within ±10 min of observed screen time. Non-agreement: Self-report is greater than ±11 min of observed screen time Unable to align: If autographer was not worn majority of the before-school or after school period (If only worn for 30 min, then removed from analysis). |

| Lifestyle | Before lessons started/ after school, how long did you spend doing homework/reading? | Agreement: Self-report aligns with amount of time observed on camera, over- or underestimating time by 15 min and below. Non-agreement: Self-report does not align with time observed on camera, over- or underestimating by greater than 15 min. Unable to align: If autographer was not worn majority of the before-school or after school period (If only worn for 30 min, then removed from analysis). |

| Lifestyle | What time did you get up yesterday? What time did you go to sleep yesterday? | Agreement: If the self-report is within ± 30 min and below of the accelerometer and autographer-derived placement/removal time. Non-agreement: If the self-report is above ± 31 min of the accelerometer and autographer-derived placement/removal time. Unable to align: If either the autographer or accelerometer was clearly placed or removed hours after or before the get up or sleep time. |

| Lifestyle | How many times did you brush your teeth yesterday? | Agreement: If some self-reported episode of brushing teeth is observed in autographer images and/or recorded in information booklet. Allow for overestimation of brushing episode by 1, e.g., twice reported but only 1 observation. Non-agreement: No observations of brushing teeth observed or self-reported removal of autographer for using bathroom in a.m./p.m. Unable to align: No observations of brushing teeth observed with the autographer or no records in log booklet of removal to use bathroom in a.m./p.m. |

References

- Waters, E.; Silva-Sanigorski, A.D.; Burford, B.J.; Brown, T.; Campbell, K.J.; Gao, Y.; Armstrong, R.; Prosser, L.; Summerbell, C.D. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Sao Paulo Medical Journal. 2014;132(2):128-9. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2014, 132, 128–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, S.C.; Seeley, R.J.; Antel, J.; Finer, N.; Heal, D.; Krause, G. Regulation of appetite, satiety and energy metabolism. In Obesity and Metabolic Disorders, Proceedings of the Fourth Solvay Pharmaceuticals Conference, Venice, Italy, 5–6 October 2003; IOS Press: Tepper Drive Clifton, VA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Trost, S.G. State of the art reviews: Measurement of physical activity in children and adolescents. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2007, 1, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, R.S.; Hoelscher, D.M.; Alexander, M.; Scanlon, K.S.; Serdula, M.K. Dietary assessment methods among school-aged children: Validity and reliability. Prev. Med. 2000, 31, S11–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, D.; Freedson, P. ActiGraph and Actical physical activity monitors: A peek under the hood. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2012, 44 (Suppl. 1), S86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welk, G.J.; Corbin, C.B.; Dale, D. Measurement issues in the assessment of physical activity in children. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2000, 71 (Suppl. 2), 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, M.; Robson, P.; Wallace, J. Issues in dietary intake assessment of children and adolescents. Br. J. Nutr. 2004, 92, S213–S222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamson, A.; Baranowski, T. Developing technological solutions for dietary assessment in children and young people. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 27, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, F.E.; Subar, A.F.; Loria, C.M.; Reedy, J.L.; Baranowski, T. Need for technological innovation in dietary assessment. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, H.J.; Hillier, F.C.; Batterham, A.M.; Ells, L.J.; Summerbell, C.D. Technology-based dietary assessment: Development of the Synchronised Nutrition and Activity Program (SNAP™). J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 27, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, S.J.; Gorely, T.; Pearson, N.; Bull, F.C. An assessment of self-reported physical activity instruments in young people for population surveillance: Project ALPHA. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntsche, E.; Ravens-Sieberer, U. Monitoring adolescent health behaviours and social determinants cross-nationally over more than a decade: Introducing the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study supplement on trends. Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25 (Suppl. 2), 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christian, D.; Todd, C.; Davies, H.; Rance, J.; Stratton, G.; Rapport, F.; Brophy, S. Community led active schools programme (CLASP) exploring the implementation of health interventions in primary schools: headteachers’ perspectives. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, H.J.; Ells, L.J.; McLure, S.A.; Crooks, S.; Cumbor, D.; Summerbell, C.D.; Batterham, A.M. The development and evaluation of a novel computer program to assess previous-day dietary and physical activity behaviours in school children: The Synchronised Nutrition and Activity ProgramTM (SNAPTM). Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 99, 1266–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biltoft-Jensen, A.; Trolle, E.; Christensen, T.; Islam, N.; Andersen, L.F.; Egenfeldt-Nielsen, S.; Tetens, I. WebDASC: A web-based dietary assessment software for 8–11-year-old Danish children. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 27, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, A.R.; Caprani, N.; Conaire, C.Ó.; Kalnikaite, V.; Gurrin, C.; Smeaton, A.F.; O’Connor, N.E. Passively recognising human activities through lifelogging. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 1948–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurrin, C.; Qiu, Z.; Hughes, M.; Caprani, N.; Doherty, A.R.; Hodges, S.E.; Smeaton, A.F. The smartphone as a platform for wearable cameras in health research. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 44, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barr, M.; Signal, L.; Jenkin, G.; Smith, M. Capturing exposures: Using automated cameras to document environmental determinants of obesity. Health Promot. Int. 2014, 30, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, M.; Signal, L.; Jenkin, G.; Smith, M. Using SenseCam to capture children’s exposure to food marketing: A feasibility study. In Proceedings of the 4th International SenseCam & Pervasive Imaging Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 18–19 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, P.; Doherty, A.; Berry, E.; Hodges, S.; Batterham, A.M.; Foster, C. Can we use digital life-log images to investigate active and sedentary travel behaviour? Results from a pilot study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, A.; Kelly, P.; Foster, C. Wearable Cameras: Identifying Healthy Transportation Choices. Ieee Pervasive Comput. 2013, 12, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, M.; Doherty, A.R.; Kelly, P.; Badland, H.M.; Mavoa, S.; Shepherd, J.; Kerr, J.; Marshall, S.; Hamilton, A.; Foster, C. Utility of passive photography to objectively audit built environment features of active transport journeys: An observational study. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2013, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, P.; Doherty, A.R.; Hamilton, A.; Matthews, A.; Batterham, A.M.; Nelson, M.; Foster, C.; Cowburn, G. Evaluating the Feasibility of Measuring Travel to School Using a Wearable Camera. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 43, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Signal, L.N.; Smith, M.B.; Barr, M.; Stanley, J.; Chambers, T.J.; Zhou, J.; Duane, A.; Jenkin, G.L.; Pearson, A.L.; Gurrin, C.; Smeaton, A.F. Kids’ Cam: An objective methodology to study the world in which children live. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 53, e89–e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, A.R.; Hodges, S.E.; King, A.C.; Smeaton, A.F.; Berry, E.; Moulin, C.J.; Lindley, S.; Kelly, P.; Foster, C. Wearable Cameras in Health. Memory 2013, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loveday, A.; Sherar, L.B.; Sanders, J.P.; Sanderson, P.W.; Esliger, D.W. Technologies That Assess the Location of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior: A Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettigrew, S.; Biagioni, N.; Jones, S.C.; Daube, M.; Kirby, G.; Stafford, J.; Chikritzhs, T. Sales promotion strategies and youth drinking in Australia. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 141, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timperio, A.; Crawford, D.; Ball, K.; Salmon, J. Typologies of neighbourhood environments and children’s physical activity, sedentary time and television viewing. Health Place 2017, 43, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.C.; Yang, H.J.; Chen, V.C.; Lee, W.T.; Teng, M.J.; Lin, C.H.; Gossop, M. Meta-analysis of quality of life in children and adolescents with ADHD: By both parent proxy-report and child self-report using PedsQL™. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 51, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egilson, S.T.; Olafsdottir, L.B.; Leosdottir, T.; Saemundsen, E. Quality of life of high-functioning children and youth with autism spectrum disorder and typically developing peers: Self-and proxy-reports. Autism 2017, 21, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelen, L.; Bundy, A.C.; Lau, J.; Naughton, G.; Wyver, S.; Bauman, A.; Baur, L. Understanding patterns of young children’s physical activity after school—It’s all about context: A cross-sectional study. J. Phys. Act. Health 2015, 12, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arundell, L.; Hinkley, T.; Veitch, J.; Salmon, J. Contribution of the after school period to children’s daily participation in physical activity and sedentary behaviours. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treuth, M.S.; Schmitz, K.; Catellier, D.J.; McMurray, R.G.; Murray, D.M.; Almeida, M.J.; Going, S.; Norman, J.E.; Pate, R. Defining accelerometer thresholds for activity intensities in adolescent girls. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2004, 36, 1259. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, R.C.; Olson, J.O.; Pepper, S.L.; Porszasz, J.A.; Barstow, T.J.; Cooper, D.M. The level and tempo of children’s physical activities: An observational study. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1995, 27, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baquet, G.; Stratton, G.; Van Praagh, E.; Berthoin, S. Improving physical activity assessment in prepubertal children with high-frequency accelerometry monitoring: A methodological issue. Prev. Med. 2007, 44, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenson, K.R.; Catellier, D.J.; Gill, K.; Ondrak, K.S.; McMurray, R.G. Calibration of two objective measures of physical activity for children. J. Sports Sci. 2008, 26, 1557–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, L.; Liu, Z.; Matthews, C.E.; Buchowski, M.S. Validation of accelerometer wear and nonwear time classification algorithm. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, A.R.; Moulin, C.J.; Smeaton, A.F. Automatically assisting human memory: A SenseCam browser. Memory 2011, 19, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, P.; Marshall, S.J.; Badland, H.; Kerr, J.; Oliver, M.; Doherty, A.R.; Foster, C. An ethical framework for automated, wearable cameras in health behavior research. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 44, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgers, N.D.; Stratton, G.; McKenzie, T.L. Reliability and validity of the System for Observing Children’s Activity and Relationships during Play (SOCARP). J. Phys. Act. Health 2010, 7, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Marshall, S.J.; Wang, L.; Godbole, S.; Legge, A.; Doherty, A.; Kelly, P.; Oliver, M.; Patterson, R.; Foster, C.; Kerr, J. Using the SenseCam as an objective tool for evaluating eating patterns. In Proceedings of the 4th International SenseCam & Pervasive Imaging Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 18–19 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, J.; Marshall, S.J.; Godbole, S.; Chen, J.; Legge, A.; Doherty, A.R.; Kelly, P.; Oliver, M.; Badland, H.M.; Foster, C. Using the SenseCam to improve classifications of sedentary behavior in free-living settings. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 44, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, P.F.; Harrell, J.S.; McMurray, R.G. Middle-School Children’s Understanding of Physical Activity: “If You’re Moving, You’re Doing Physical Activity”. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2008, 23, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trost, S.G.; Morgan, A.M.; Saunders, R.; Felton, G.; Ward, D.S.; Pate, R.R. Children’s understanding of the concept of physical activity. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2000, 12, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keadle, S.K.; Lyden, K.; Hickey, A.; Ray, E.L.; Fowke, J.H.; Freedson, P.S.; Matthews, C.E. Validation of a previous day recall for measuring the location and purpose of active and sedentary behaviors compared to direct observation. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin Bland, J.; Altman, D. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986, 327, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkimer, J.C.; Brown, J.H. Back to basics: Percentage agreement measures are adequate, but there are easier ways. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1979, 12, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridgers, N.D.; Knowles, Z.R.; Sayers, J. Encouraging play in the natural environment: A child-focused case study of Forest School. Child. Geogr. 2012, 10, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, Z.; Gilbourne, D.; Borrie, A.; Nevill, A. Developing the reflective sports coach: A study exploring the processes of reflective practice within a higher education coaching programme. Reflective Pract. 2001, 2, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, S.D.; Thompson, W.O. Accuracy by meal component of fourth-graders’ school lunch recalls is less when obtained during a 24-hour recall than as a single meal. Nutr. Res. 2002, 22, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, S.D.; Thompson, W.O.; Litaker, M.S.; Guinn, C.H.; Frye, F.H.; Baglio, M.L.; Shaffer, N.M. Accuracy of fourth-graders’ dietary recalls of school breakfast and school lunch validated with observations: In-person versus telephone interviews. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2003, 35, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.L.; Lytle, L.; Gittelsohn, J.; Cunningham-Sabo, L.; Heller, K.; Anliker, J.A.; Stevens, J.; Hurley, J.; Ring, K. Validity of self-reported dietary intake at school meals by American Indian children: The Pathways Study. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2004, 104, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, A.S.; Baranowski, J.; Islam, N.; Baranowski, T. How to engage children in self-administered dietary assessment programmes. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 27, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, S.D.; Thompson, W.O.; Davis, H.C.; Johnson, M.H. Impact of gender, ethnicity, meal component, and time interval between eating and reporting on accuracy of fourth-graders’ self-reports of school lunch. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1997, 97, 1293–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, A. Designing and testing questionnaires for children. J. Res. Nurs. 2007, 12, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandewater, E.A.; Lee, S.-J. Measuring children’s media use in the digital age issues and challenges. Am. Behav. Sci. 2009, 52, 1152–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telford, A.; Salmon, J.; Jolley, D.; Crawford, D. Reliability and validity of physical activity questionnaires for children: The Children’s Leisure Activities Study Survey (CLASS). Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2004, 16, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedišić, Ž.; Bauman, A. Accelerometer-based measures in physical activity surveillance: Current practices and issues. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, A.R.; Kelly, P.; Kerr, J.; Marshall, S.; Oliver, M.; Badland, H.; Hamilton, A.; Foster, C. Using wearable cameras to categorise type and context of accelerometer-identified episodes of physical activity. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gemming, L.; Doherty, A.; Utter, J.; Shields, E.; Mhurchu, C.N. The use of a wearable camera to capture and categorise the environmental and social context of self-identified eating episodes. Appetite 2015, 92, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavoa, S.; Oliver, M.; Kerr, J.; Doherty, A.; Witten, K. Using SenseCam images to assess the environment. In Proceedings of the 4th International SenseCam & Pervasive Imaging Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 18–19 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cowburn, G.; Matthews, A.; Doherty, A.; Hamilton, A.; Kelly, P.; Williams, J.; Foster, C.; Nelson, M. Exploring the opportunities for food and drink purchasing and consumption by teenagers during their journeys between home and school: A feasibility study using a novel method. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 19, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Mariappan, A.; Boushey, C.J.; Kerr, D.; Lutes, K.D.; Ebert, D.S.; Delp, E.J. Technology-assisted dietary assessment. In Electronic Imaging 2008; International Society for Optics and Photonics: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Spruijt-Metz, D.; Wen, C.K.; Bell, B.M.; Intille, S.; Huang, J.S.; Baranowski, T. Advances and controversies in diet and physical activity measurement in youth. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 55, e81–e91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Question |

|---|---|

| 1 | What time did you get up yesterday? |

| 2 | What did you eat for breakfast yesterday? |

| 3 | What did you drink for breakfast yesterday? |

| 4a | Before lessons started, how long did you spend doing sports or exercise? |

| 4b | Before lessons started, how long did you spend sitting down watching TV/playing video games/using iPad/internet? |

| 4c | Before lessons started, how long did you spent doing homework or reading? |

| 5a | How did you get to school? |

| 5b | Did you travel with an adult? |

| 6 | What did you do for most of your morning break? |

| 7a | What did you have to eat for lunch? |

| 7b | What did you have to drink for lunch? |

| 8 | Apart from eat your food, what did you do for most of your lunchtime break? |

| 9 | What did you do for most of your afternoon break? |

| 10a | How did you travel home from school? |

| 10b | Did you travel with an adult? |

| 11a | After school, how long did you spend doing sports or exercise? |

| 11b | After school, how long did you spend sitting down watching TV, playing video games/using iPad/internet? |

| 11c | After school, how long did you spend doing homework or reading? |

| 12 | How many portions of fruit and veg did you eat yesterday? |

| 13 | How many times did you brush your teeth yesterday? |

| 14 | What time did you go to sleep? |

| Question | n | Agreement | % Agreement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before lessons started, how long did you spend doing sports or exercise? | 12 | 5 | 42 |

| After school how long did you spend doing sports or exercise? | 11 | 8 | 73 |

| What did you have for breakfast yesterday? | 12 | 9 | 75 |

| What did you do for most of your morning break intensity? | 13 | 7 | 54 |

| What did you have to eat for lunch? | 14 | 14 | 100 |

| What did you do for most of your lunchtime? | 13 | 8 | 62 |

| What did you do for most of your afternoon break? | 13 | 5 | 38 |

| How did you get to school yesterday morning? | 14 | 13 | 93 |

| Did you travel with an adult? | 14 | 13 | 93 |

| How did you get home yesterday? | 10 | 9 | 90 |

| Did you travel with an adult? | 10 | 9 | 90 |

| What did you drink for breakfast yesterday? | 12 | 3 | 25 |

| What did you drink for lunch yesterday? | 14 | 8 | 57 |

| How many portions of fruit and vegetables? | 12 | 6 | 50 |

| How many times did you brush your teeth yesterday? | 10 | 10 | 100 |

| What time did you get up yesterday? | 12 | 11 | 93 |

| What time did you go to sleep? | 6 | 5 | 83 |

| Before-school screen time | 12 | 6 | 50 |

| After school screen time | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Before-school time spent on homework | 12 | 8 | 67 |

| After school time spent on homework | 7 | 5 | 71 |

| Question | n | Agreement | % Agreement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before lessons started, how long did you spend doing sports or exercise? | 12 | 4 | 33 |

| What did you do for most of your morning break yesterday? | 14 | 8 | 57 |

| What did you do for most of your lunchtime? | 14 | 10 | 71 |

| What did you do for most of your afternoon break? | 14 | 6 | 46 |

| After school how long did you spend doing sports or exercise? | 13 | 7 | 54 |

| How did you get to school yesterday morning? | 14 | 13 | 93 |

| How did you get home yesterday? | 10 | 11 | 91 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Everson, B.; Mackintosh, K.A.; McNarry, M.A.; Todd, C.; Stratton, G. Can Wearable Cameras Be Used to Validate School-Aged Children’s Lifestyle Behaviours? Children 2019, 6, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/children6020020

Everson B, Mackintosh KA, McNarry MA, Todd C, Stratton G. Can Wearable Cameras Be Used to Validate School-Aged Children’s Lifestyle Behaviours? Children. 2019; 6(2):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/children6020020

Chicago/Turabian StyleEverson, Bethan, Kelly A. Mackintosh, Melitta A. McNarry, Charlotte Todd, and Gareth Stratton. 2019. "Can Wearable Cameras Be Used to Validate School-Aged Children’s Lifestyle Behaviours?" Children 6, no. 2: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/children6020020

APA StyleEverson, B., Mackintosh, K. A., McNarry, M. A., Todd, C., & Stratton, G. (2019). Can Wearable Cameras Be Used to Validate School-Aged Children’s Lifestyle Behaviours? Children, 6(2), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/children6020020