1. Introduction

Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN) is a disorder of unsuccessful circulatory transition at birth [

1]. It is characterized by the extrapulmonary shunting of blood at the level of the patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) and patent foramen ovale (PFO), resulting in hypoxemia. Labile hypoxemia and a preductal to postductal oxygen saturation by the pulse oximetry (SpO

2) gradient are classic features of PPHN. The pre- and postductal gradient is thought to be secondary to right-to-left or bidirectional shunting across the PDA [

2]. This gradient can be measured using simultaneous arterial blood gases (ABG) or by pulse oximetry.

As part of the screening for critical congenital heart disease (CCHD), an oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry (SpO

2) gradient of > 3% [

3] is taken as an indication for further testing [

4]. This screening method often detects conditions such as PPHN in addition to CCHD [

5,

6,

7]. However, there are no studies directly measuring the relation of ductal shunts to simultaneous pre- and postductal blood gases.

We evaluated the relationship between the direction of ductal shunt and blood gas parameters in simultaneous preductal (right carotid) and postductal (umbilical artery) samples in a lamb model of meconium aspiration syndrome (MAS) with PPHN. We hypothesized that the presence of a bidirectional or right-to-left shunt at the PDA will be associated with a clinically significant gradient between the pre- and postductal partial arterial oxygen tension (PaO2) and saturation of arterial oxygen (SaO2) concentrations.

2. Materials and Methods

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC, protocol #20267) at the University of California Davis (UCD) and has been described in detail previously [

8,

9,

10]. This institution is accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, International (AAALAC). UCD has an Animal Welfare Assurance on file with the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare (OLAW). The Assurance Number is D16-00272 (A3433-01). The IACUC is constituted in accordance with the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) Animal Welfare Policy and includes a member of the public and a non-scientist.

2.1. Animal Preparation

Time-dated near-term (138–141 day gestation; term ~145 days) pregnant ewes were bred by Van Laningham Farm, Arbuckle, CA, USA. Following an overnight fast, the ewe was sedated with intravenous propofol or diazepam and ketamine. The ewe was then intubated with a 9.5-mm cuffed endotracheal tube (ETT), provided general anesthesia with 2–4% inhaled isoflurane, and continuously monitored with a pulse oximeter and an end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) monitor. Following a laparotomy, the fetal lamb was partially exteriorized and intubated with a 4.5-mm cuffed endotracheal tube (ETT). The fetal lung fluid in the ETT was passively drained by lowering the head and, thereafter, the ETT was occluded to prevent gas exchange during gasping, following asphyxiation by cord occlusion. Under maternal anesthesia, and after infiltrating the site with subcutaneous bupivacaine, an incision was made to place a catheter in the lamb’s right carotid artery for the measurement of blood pressures and the collection of blood samples. The right jugular vein was catheterized for fluid and medication administration. A 3-mm flow probe (Transonic, Ithaca, NY, USA) was placed around the left carotid to measure the blood flow. A left thoracotomy was performed for placement of flow probes to measure blood flow in the left pulmonary artery (QP; 4-mm probe) and the ductus arteriosus (QDA; 6-mm probe). Finally, both the thoracotomy and neck incisions were surgically closed. The baseline hemodynamic measurements and arterial blood gases were recorded.

2.2. Experimental Protocol

After instrumentation and baseline measurements, a 30 mL syringe was attached to the ETT and a 20% solution of meconium in amniotic fluid (approximately 5 mL/kg) was instilled into the ETT. Intravenous analgesic support was started prior to cord clamping. Acute prenatal asphyxiation was induced by occluding the umbilical cord for five minutes or until the heart rate decreased below 40 beats per minute. During this time period, the meconium solution was “spontaneously” aspirated during gasping and distributed into the lungs. The umbilical cord compression was relieved for two minutes to allow for hemodynamic recovery, followed by a second five-minute cord occlusion interval. Following meconium aspiration, the umbilical cord was tied and cut, and the lambs were delivered.

The lambs were transferred to a radiant warmer and mechanically ventilated. The peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) was adjusted based on the exhaled tidal volume, ETCO

2, and partial arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO

2). A catheter was then placed in the umbilical artery to collect postductal blood samples. A pulse oximeter was placed on the right forelimb for continuous saturation monitoring (SpO

2). A second pulse oximeter was placed around a hind limb for postductal SpO

2 measurements. The inspired oxygen concentration was adjusted to achieve a preductal SpO

2 as per the Neonatal Resuscitation Program guidelines for the first 15 min. Subsequent management was based on the consensus statement from the European Pediatric Pulmonary Vascular Disease Network (EPPVDN) [

11]. We targeted a preductal SpO

2 between 91% and 95%, a PaO

2 between 50 and 70 mmHg, and a PaCO

2 between 45 and 60 mmHg. Lambs were monitored for up to six hours, whereupon the blood gases and hemodynamic data were analyzed at 15 min intervals. At the completion of the study period, the lambs were euthanized.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Blood gases were analyzed using a blood gas analyzer (Radiometer ABL90 FLEX, Denmark), and hemodynamic variables were continuously recorded using computer acquisition and analysis software (BIOPAC Systems, Goleta, CA, USA). The ductal flow (systolic maximum, diastolic minimum, and mean) was recorded simultaneously at the time of the pre- and postductal blood gas sampling. Blood gas variables, specifically SaO2, and flows are expressed as means with standard deviations (SDs). By convention, the right-to-left ductal flow was labeled negative and the left-to-right flow was labeled positive on the acquisition device. The ductal flow was recorded as the minimum (diastolic flow), mean, and maximum (systolic flow). Throughout the analysis, the right-to-left or bidirectional ductal shunting was defined by values with negative (right-to-left) flow either during the diastole, systole, or both phases of the cardiac cycle. The left-to-right ductal shunting was defined by positive flow throughout the cardiac cycle. We also evaluated the hemodynamic and gas exchange implications of a pre- and postductal SaO2 gradient of ≥ 3% and < 3%. The pre- and postductal comparisons were analyzed by a two-tailed, paired Student’s t-test. Comparisons between the right-to-left/bidirectional and left-to-right ductal shunt groups were analyzed using a two-tailed, Student’s t-test with unequal variances. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.01.

3. Results

A total of 129 hemodynamic and blood gas time-points were compiled and sorted into right-to-left/bidirectional and left-to-right ductal shunt groups based on the ductal blood flow direction (

Table 1).

The blood gas and hemodynamic parameters were also classified based on the pre- to postductal SaO

2 gradient (

Table 2). The hemoglobin, preductal SpO

2, pH, blood lactate, fractional inspired oxygen (FiO

2), and mean airway pressures were not significantly different between these two groups.

3.1. Shunting and Ductal Blood Flow

Blood gas samples drawn during the presence of right-to-left (or bidirectional) ductal shunting (as defined in the methodology) had significantly lower postductal PaO

2 values and significantly higher preductal and postductal PaCO

2 values compared to the samples drawn in the presence of left-to-right shunting (

Table 1). Only two instances of exclusive right-to-left shunting throughout the cardiac cycle were observed in the right-to-left (or bidirectional) ductal shunting, and hence this group is henceforth referred as the bidirectional shunt group. The left-to-right ductal flow is an important contributor to pulmonary blood flow, and samples with a bidirectional shunt had a lower Q

P when plotted against the preductal PaO

2 (

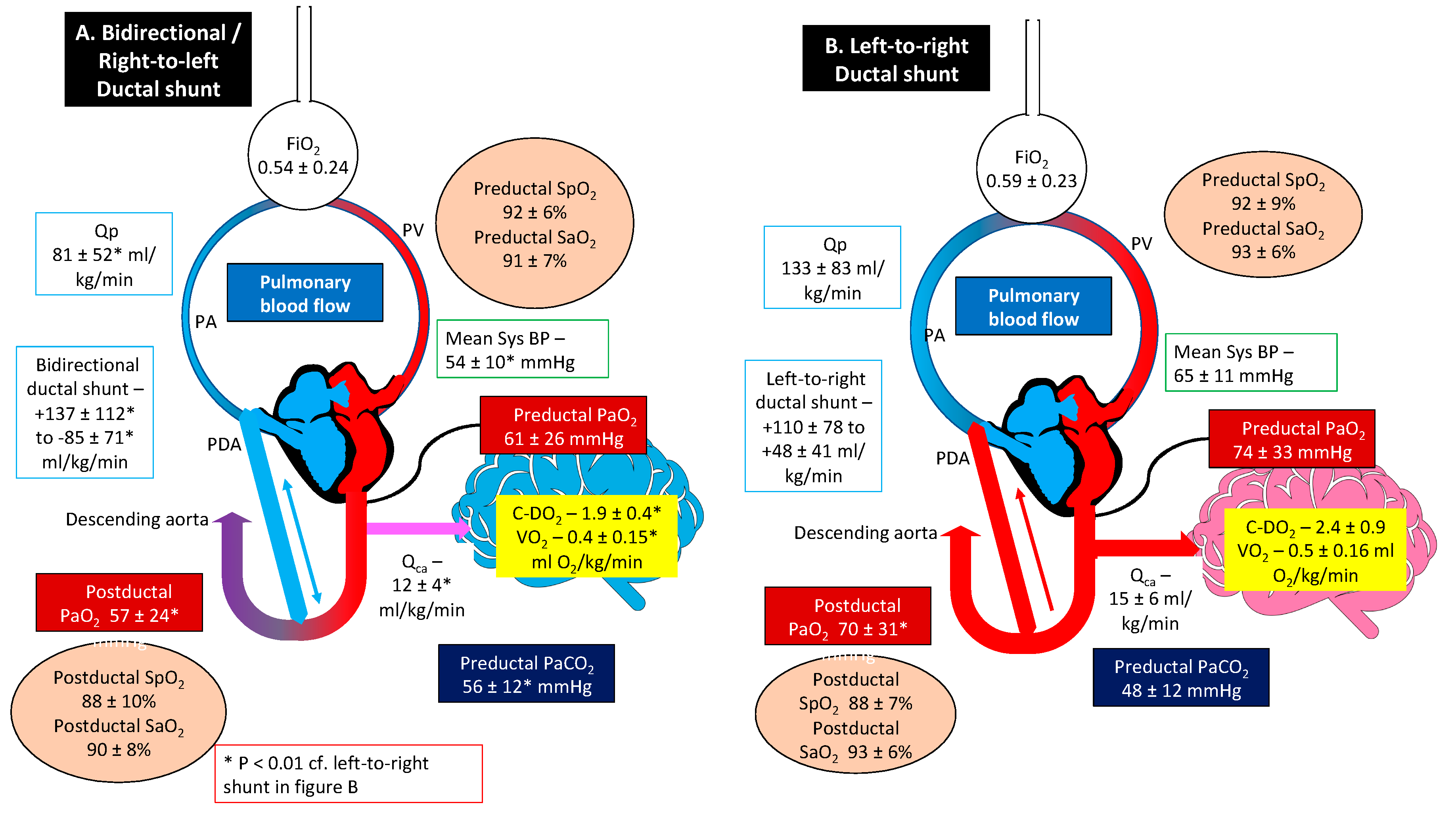

Figure 1).

Mean systemic blood pressure was significantly lower in the bidirectional group compared to the left-to-right ductal shunt group (53 ± 12 vs. 68 ± 10 mm Hg, p < 0.01). The left QCA was significantly lower in the bidirectional shunt group (12.1 ± 3.9 vs. 14.6 ± 5.7 mL/kg/min, p < 0.01).

Analysis within groups revealed that the postductal arterial oxygen content (CaO

2) and SaO

2 were significantly lower than their preductal counterparts during bidirectional shunting (

Table 1). There was no significant difference between the pre- and postductal CaO

2 and SaO

2 values in the presence of left-to-right shunting (

Table 1). When evaluating for the oxygenation index (OI), the preductal samples were significantly lower than the postductal samples regardless of the group/shunting directionality, with no difference in OI between the bidirectional group compared to the left-to-right ductal shunt group (

Table 1). Oxygen delivery to the brain was calculated by multiplying the carotid blood flow with the preductal arterial oxygen content (Q

CA × CaO

2/100). Oxygen consumption by the brain was calculated using the following equation Q

CA × (CaO

2 − CvO

2)/100, where CaO

2 is the carotid arterial oxygen content and CvO

2 is the jugular venous oxygen content. The brain oxygen delivery and oxygen consumption by the brain were lower in the bidirectional shunt group (

Table 1). A representative BIOPAC image of bidirectional shunt and left-to-right shunt are shown in

Figure 2.

3.2. Shunting and Pre- and Postductal Difference in SaO2

Samples with a pre- and postductal oxygen saturation gradient of ≥ 3% had a lower pre- and postductal SaO

2, lower preductal PaO

2, and higher PaCO

2 compared to the < 3% group (

Table 2). The mean airway pressure and FiO

2 were similar between the two groups. When analyzing the pre- and postductal arterial saturation differences, 56% of samples with a bidirectional or right-to-left shunt had a pre- and postductal saturation difference of < 3% (

Table 2). However, only 11% of the samples containing a ≥ 3% difference were associated with exclusive left-to-right shunts (

Table 2).

A graphic summary of the results is presented in

Figure 3.

4. Discussion

Extrapulmonary shunt at the PDA and PFO level leading to hypoxemia is characteristic of PPHN. Birth asphyxia with meconium aspiration is a common cause of PPHN in term infants [

12]. The presence of right-to-left ductal shunting is inferred by the presence of an oxygenation gradient between the pre- and postductal regions. In this study, using a model of birth asphyxia, meconium aspiration syndrome, and secondary PPHN, we demonstrate that bidirectional ductal shunting with hypoxemia can occur without a significant pre- to postductal oxygenation gradient.

There are several limitations to this study. The degree of hypoxemic respiratory failure was mild to moderate. We did not evaluate shunting at the PFO level. Significant right-to-left shunting at the PFO may potentially reduce the pre- and postductal oxygen gradient. We did not consistently measure the postductal SpO

2 in all lambs due to the lack of an adequate number of pulse oximeters during multiple, simultaneous studies. The degree of right-to-left shunting may potentially be more significant in the presence of severe hypoxemia and PPHN. The ovine model of severe PPHN can be induced by antenatal ductal ligation [

13]. However, it is not possible to assess ductal shunting in this model. We did not measure the pulmonary arterial pressure in these studies and did not assess the severity of PPHN. We did document hypoxemia, low pulmonary blood flow, and bidirectional or right-to-left shunting (2 samples) in this study, and these findings are suggestive of PPHN. Finally, we did not statistically correct for multiple values obtained from the same lamb. There was widespread fluctuation in the direction of shunting, pulmonary blood flow, and blood gases in the same lamb with time.

The novel aspect of the study is the simultaneous measurement of ductal, pulmonary, and carotid flows along with pre- and postductal blood gases. A right-to-left or bidirectional flow at the ductus is associated with a significant reduction in the pulmonary blood flow, leading to significantly lower PaO2/FiO2 ratios in these lambs. The presence of a bidirectional shunt was also associated with lower systemic blood pressures and a higher PaCO2. Despite high PaCO2 concentrations, the carotid blood flow, oxygen delivery, and oxygen consumption by the brain were significantly lower in the presence of a bidirectional shunt. This suggests that oxygen delivery to the brain is compromised in the presence of bidirectional shunt in this model.

In neonates with PPHN the absence of a pre- and postductal oxygenation gradient is thought to be due to the closure of the PDA or an exclusively left-to-right shunt at the PDA [

1]. The current study shows that even in the presence of a low pulmonary blood flow and bidirectional ductal shunt, there may not be a significant saturation or PaO

2 gradient between the preductal and postductal regions. The oxygen saturation in the lower limb is dependent on the admixture of pulmonary arterial blood (with a mixed venous oxygen saturation of 70% ± 9% in our study) and preductal arterial blood (with SaO

2 of 90.9% ± 6.5%). Using the shunt equation, the right-to-left effective ductal shunt only contributes to 6.6% of the descending aortic flow in lambs with a bidirectional ductal flow. The presence of a saturation difference between the preductal and postductal samples is a reliable indicator of PPHN and a bidirectional or right-to-left shunt (89% of instances—

Table 2). However, the absence of a saturation gradient between the preductal and postductal samples does not rule out PPHN despite the presence of hypoxemia with compromised oxygen delivery to the brain.

5. Conclusions

In lambs with parenchymal lung disease and secondary PPHN, the presence of a pre- and postductal oxygenation gradient was indicative of a right-to-left or bidirectional shunt. However, the lack of a pre- and postductal oxygenation gradient does not rule out bidirectional shunt. In clinical situations with parenchymal lung disease, the clinical absence of a pre- and postductal oxygenation gradient should not be considered to suggest the absence of PPHN, and higher emphasis should be placed on obtaining echocardiography to confirm the diagnosis.

Author Contributions

A.L.: data extraction and analysis, conducting experiments, and writing the manuscript; M.H.: data extraction and analysis, conducting experiments, and critiquing and writing the manuscript; W.F.: conducting experiments and critiquing manuscript; S.L.: concept, analysis of data, and critiquing and writing the manuscript; P.V.: concept, conducting studies, analysis of data, and critiquing and writing the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been supported by NIH grants HD096299 (PV) and HD072929 (SL).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lakshminrusimha, S.; Keszler, M. Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Neoreviews 2015, 16, e680–e692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nair, J.; Lakshminrusimha, S. Update on PPHN: Mechanisms and treatment. Semin. Perinatol. 2014, 38, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kemper, A.R.; Mahle, W.T.; Martin, G.R.; Cooley, W.C.; Kumar, P.; Morrow, W.R.; Kelm, K.; Pearson, G.D.; Glidewell, J.; Grosse, S.D.; et al. Strategies for implementing screening for critical congenital heart disease. Pediatrics 2011, 128, e1259–e1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mahle, W.; Koppel, R. Screening with pulse oximetry for congenital heart disease. Lancet 2011, 378, 749–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, N.; Lakshminrusimha, S. The limitations of pulse oximetry for critical congenital heart disease screening in the neonatal intensive care units. Acta Paediatr. 2017, 106, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manja, V.; Mathew, B.; Carrion, V.; Lakshminrusimha, S. Critical congenital heart disease screening by pulse oximetry in a neonatal intensive care unit. J. Perinatol. Off. J. Calif. Perinat. Assoc. 2015, 35, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van Naarden Braun, K.; Grazel, R.; Koppel, R.; Lakshminrusimha, S.; Lohr, J.; Kumar, P.; Govindaswami, B.; Giuliano, M.; Cohen, M.; Spillane, N.; et al. Evaluation of critical congenital heart defects screening using pulse oximetry in the neonatal intensive care unit. J. Perinatol. Off. J. Calif. Perinat. Assoc. 2017, 37, 1117–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakshminrusimha, S.; Mathew, B.; Nair, J.; Gugino, S.F.; Koenigsknecht, C.; Rawat, M.; Nielsen, L.; Swartz, D.D. Tracheal suctioning improves gas exchange but not hemodynamics in asphyxiated lambs with meconium aspiration. Pediatr. Res. 2015, 77, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rawat, M.; Chandrasekharan, P.; Gugino, S.F.; Koenigsknecht, C.; Nielsen, L.; Wedgwood, S.; Mathew, B.; Nair, J.; Steinhorn, R.; Lakshminrusimha, S. Optimal oxygen targets in term lambs with meconium aspiration syndrome and pulmonary hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawat, M.; Chandrasekharan, P.K.; Swartz, D.D.; Mathew, B.; Nair, J.; Gugino, S.F.; Koenigsknecht, C.; Vali, P.; Lakshminrusimha, S. Neonatal resuscitation adhering to oxygen saturation guidelines in asphyxiated lambs with meconium aspiration. Pediatr. Res. 2016, 79, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hansmann, G.; Koestenberger, M.; Alastalo, T.P.; Apitz, C.; Austin, E.D.; Bonnet, D.; Budts, W.; D’Alto, M.; Gatzoulis, M.A.; Hasan, B.S.; et al. 2019 updated consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric pulmonary hypertension: The European Pediatric Pulmonary Vascular Disease Network (EPPVDN), endorsed by AEPC, ESPR and ISHLT. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2019, 38, 879–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Steurer, M.A.; Jelliffe-Pawlowski, L.L.; Baer, R.J.; Partridge, J.C.; Rogers, E.E.; Keller, R.L. Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn in late preterm and term infants in California. Pediatrics 2017, 139, e20161165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lakshminrusimha, S.; Russell, J.A.; Wedgwood, S.; Gugino, S.F.; Kazzaz, J.A.; Davis, J.M.; Steinhorn, R.H. Superoxide dismutase improves oxygenation and reduces oxidation in neonatal pulmonary hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 174, 1370–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).