Development of the Dutch Structure for Integrated Children’s Palliative Care

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Children’s Palliative Care Worldwide

1.2. Situation CPC in the Netherlands

1.3. Exploration of an Appropriate Approach of CPC

2. Approach

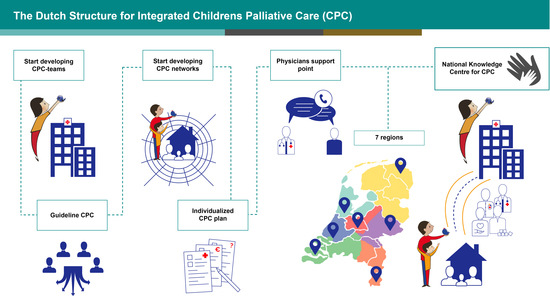

| CPC teams in hospitals: This is a multidisciplinary team consisting of specialised children’s nurses, paediatricians, psychologists and child life specialists and is the bridge between hospital and home. The team offers support and guidance to families and first-line care by the family physician and homecare team. This care demands a professional and coordinating approach to support the whole family during the difficult process of palliative care. |

| CPC networks: This is a collaboration of professionals from different disciplines (specialised nurses, paediatric homecare nurses, paediatricians, general practitioners, social workers, psychologists, paramedics, child life specialists, day care facilities, bereavement care, spiritual workers, client support) and organisations involved in care from hospital to home, with specific expertise in caring for families with a severely ill child. These cross-domain networks offer support and guidance for families and focus on balance and everyday life for the whole family. Moreover, the networks fulfil a free access consultation function for parents and professionals who have questions about CPC. Another important task of the CPC networks is to increase and exchange expertise in the region via regular interprofessional meetings. |

Evaluation and Improvement

3. Results

- Recognition of CPC as a specialised field of care;

- Focus not only on medical aspects but an integrated multidisciplinary approach;

- Focus on the whole family: the ill child, parents and siblings;

- Care can be given at home more often; fewer (re)admissions to hospital;

- A careful transfer of a palliative process from hospital to home, actively prepared and discussed with child and parents;

- Space for daily family life by relieving of parents from organisational tasks and arranging care at home;

- Provision of bereavement care and aftercare.

Recent Developments

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sepúlveda, C.; Marlin, A.; Yoshida, T.; Ullrich, A. World Health Organization’s Global Perspective; World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenkamp, C.M.; Hamers, J.P.H.; Courtens, A.M. Palliatieve Zorg Voor Kinderen: Maatwerk Vereist. Een Exploratieve Studie Naar Zorgbehoeften, Aanbod, Knelpunten en Mogelijke Oplossingen; Cluster Zorgwetenschappen, Sectie Verplegingswetenschap, Universiteit Maastricht: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg, M. Towards Good Practices in Children’s Palliative Care. An Assessment of Research and Practice. Publication of Foundation Children’s Palliative Expertise. 2009. Available online: https://adoc.pub/op-weg-naar-goede-praktijken-in-de-kinderpalliatieve-zorg83aa0c3326623a24402b4f4fee614d6880888.html (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- ACT/RCPCH. A Guide to the Development of Children’s Palliative Care Services, 4th ed.; 2018; Available online: https://www.togetherforshortlives.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/TfSL-A-Guide-to-Children’s-Palliative-Care-Fourth-Edition-5.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Liben, S.; Papadatou, D.; Wolfe, J. Paediatric palliative care: Challenges and emerging ideas. Lancet 2008, 371, 852–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Children’s Palliative Care Network (ICPCN). Figure provision of CPC. Available online: https://www.icpcn.org/1949-2/ (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- International Children’s Palliative Care Network (ICPCN). Home Page. Available online: https://www.icpcn.org (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- CBS StatLine. StatLine the Deceased; Major Causes of Death (Short List), Age, Gender. Available online: https://opendata.cbs.nl/statline/#/CBS/nl/dataset/7052_95/table?ts=1566378924628 (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Advisory Council on Health Research. Diseases in Childhood: Research for Health; Health Council of the Netherlands: The Haque, The Netherlands, RGO 2010. nr. 62; Available online: https://ris.utwente.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/5146161/kind.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Van Hal, L.; Tierolf, B.; van Rooijen, M.; van der Hoff, M. A Current Perspective on Children and Young People with a Chronic Condition in The Neterlands, Size, Composition and Participation; Verwey-Jonker Institute: Utrecht, the Netherland, 2019; Available online: https://www.verwey-jonker.nl/publicatie/een-actueel-perspectief-op-kinderen-en-jongeren-met-een-chronische-aandoening-in-nederland-omvang-samenstelling-en-participatie/ (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Palliative Care Figures. Expertise Square for Care. Available online: https://www.zorgvoorbeter.nl/palliatieve-zorg/cijfers (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Foundation Child and Hospital; Association Paediatric Nursing in the Netherlands; Foundation Children’s Palliative Expertise; Foundation Childcare at Home. Serious Ill Children Are Entitled to Good Care. 2013. Available online: https://docplayer.nl/16106653-Ernstig-zieke-kinderen-hebben-recht-op-gezonde-zorg-op-weg-naar-participatie-in-de-samenleving.html (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Foundation Child and Hospital; Foundation Children’s Palliative Expertise; Paediatric Association of the Netherlands; Association Paediatric Nursing in the Netherlands; Foundation Specialized Nursing Childcare; Foundation Partnership Respiratory Support; Foundation Childcare at Home. Together on the Road to Healthy Care for Serious Ill Children. 2014. Available online: https://www.kinderpalliatief.nl/professionals/kennis/publicaties/publicatie/samen-op-weg-naar-gezonde-zorg (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Theunissen, J.M.J.; Hoogerbrugge, P.M.; van Achterberg, A.T.; Prins, J.B.; Vernooij-Dassen, M.J.; van den Ende, C.H. Symptoms in the palliative phase of children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2007, 49, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galesloot, C.; Stoelinga, W.; Groot, M. Van Willekeur Naar Wenselijkheid. Eindrapport Project Kinderpalliatieve Zorg; Integraal kankercentrum Oost: Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, B.S.; Howenstein, M.; Gilmer, M.J.; Throop, P.; France, D.; Whitlock, A.J. Circumstances surrounding the deaths of hospitalized children: Opportunities for pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics 2004, 114, e361–e366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Loeffen, E.A.H.; Tissing, W.J.E.; Schuiling-Otten, M.A.; De Kruiff, C.C.; Kremer, L.C.M.; Verhagen, A.A.E. Individualised advance care planning in children with life-limiting conditions. Arch. Dis. Child. 2017, 103, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagt-vanKampen, C.T.; Kars, M.C.; Colenbrander, D.A.; Bosman, D.K.; Grootenhuis, M.A.; Caron, H.N.; Schouten-vanMeeteren, A.Y.N. A prospective study on the characteristics and subjects of pediatric palliative care case management provided by a hospital based palliative care team. BMC Palliat. Care 2017, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jagt-vanKampen, C.T.; Colenbrander, D.A.; Bosman, D.K.; Grootenhuis, M.A.; Kars, M.C.; Schouten-vanMeeteren, A.Y.N. Aspects and intensity of Pediatric Palliative Case Management provided by a hospital-based case management team: A comparative study between children with malignant and nonmalignant disease. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2018, 35, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verberne, L.M.; Schouten, A.Y.S.-v.M.; Bosman, D.K.; Colenbrander, D.A.; Jagt, C.T.-v.K.; Grootenhuis, M.A.; van Delden, J.J.; Kars, M.C. Parental experiences with a paediatric palliative care team; A qualitative study. Palliat. Med. 2017, 31, 956–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Verberne, L.M.; Kars, M.C.; Meeteren, A.Y.N.-V.; Bosman, D.K.; Colenbrander, D.A.; Grootenhuis, M.A.; Van Delden, J.J.M. Aims and tasks in parental caregiving for children receiving palliative care at home: A qualitative study. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2017, 176, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vallianatos, S.; Business Model Emma Home Team. Publication of Foundation Children’s Palliative Expertise. 2015. Available online: https://www.kinderpalliatief.nl/Portals/14/Documenten/BusinessmodelETt_juni2015%201.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Paediatric Association of the Netherlands. Guideline: Palliative Care for Children. 2013. Available online: https://www.nvk.nl/themas/kwaliteit/richtlijnen/richtlijn?componentid=6881317&tagtitles=Erfelijke%252ben%252baangeboren%252baandoeningen%2cIntensive%252bCare%2cNeonatologie%2cOncologie%2cSociale%252ben%252bPsychosociale%252bkindergeneeskunde%2cMetabole%252bZiekten%2cNeurologie%2cPalliatief (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Minkman, M.M. Developing integrated care. Towards a development model for integrated care. Int. J. Integr. Care 2012, 12, e197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- PAL Foundation; Vilans, Centre of Expertise for Long Term Care. Towards Integrated Children’s Palliative Care. Model in 10 Steps. A Publication of PAL Foundation. 2015. Available online: https://www.kinderpalliatief.nl/Portals/14/Documenten/Basismodel-netwerkKPZ-DEF.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Mul, M.; Spiegelbijeenkomsten, Y. Methode van Feedback Voor Patiënten; Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vallianatos, S.; Huizinga, C.S.M.; Schuiling-Otten, M.A.; Schouten-van Meeteren, A.Y.N.; Kremer, L.C.M.; Verhagen, A.A.E. Development of the Dutch Structure for Integrated Children’s Palliative Care. Children 2021, 8, 741. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8090741

Vallianatos S, Huizinga CSM, Schuiling-Otten MA, Schouten-van Meeteren AYN, Kremer LCM, Verhagen AAE. Development of the Dutch Structure for Integrated Children’s Palliative Care. Children. 2021; 8(9):741. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8090741

Chicago/Turabian StyleVallianatos, Stephanie, Carolien S. M. Huizinga, Meggi A. Schuiling-Otten, Antoinette Y. N. Schouten-van Meeteren, Leontien C. M. Kremer, and A. A. Eduard Verhagen. 2021. "Development of the Dutch Structure for Integrated Children’s Palliative Care" Children 8, no. 9: 741. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8090741