Impact of Drinking Water Source and Sanitation Facility on Malnutrition Prevalence in Children under Three: A Gender-Disaggregated Analysis Using PDHS 2017–18

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Dependent Variables

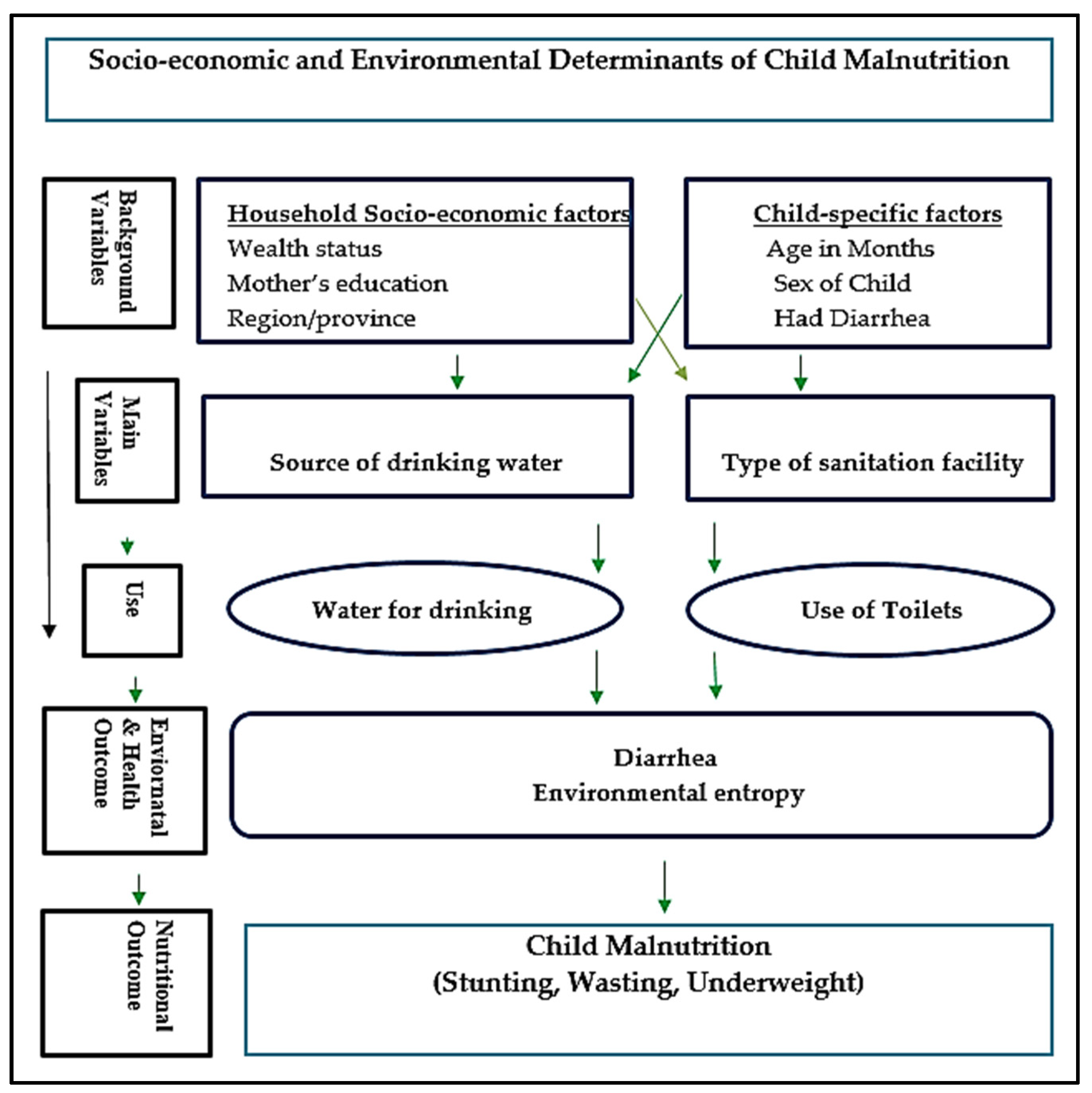

2.3. Independent Variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

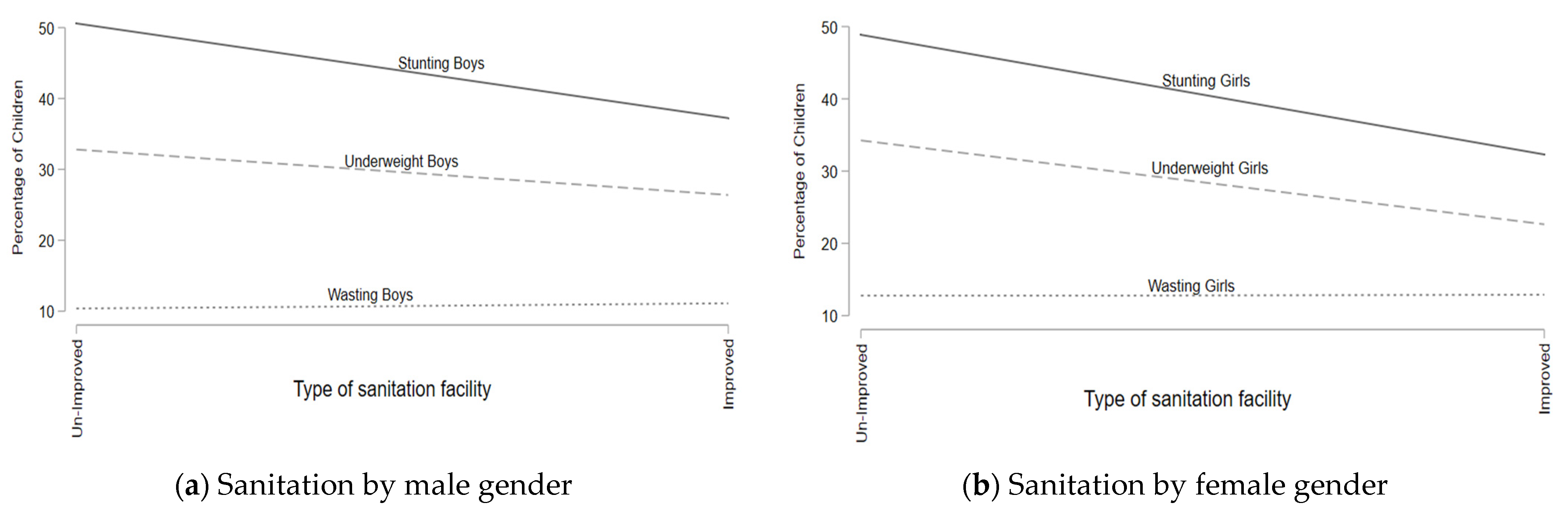

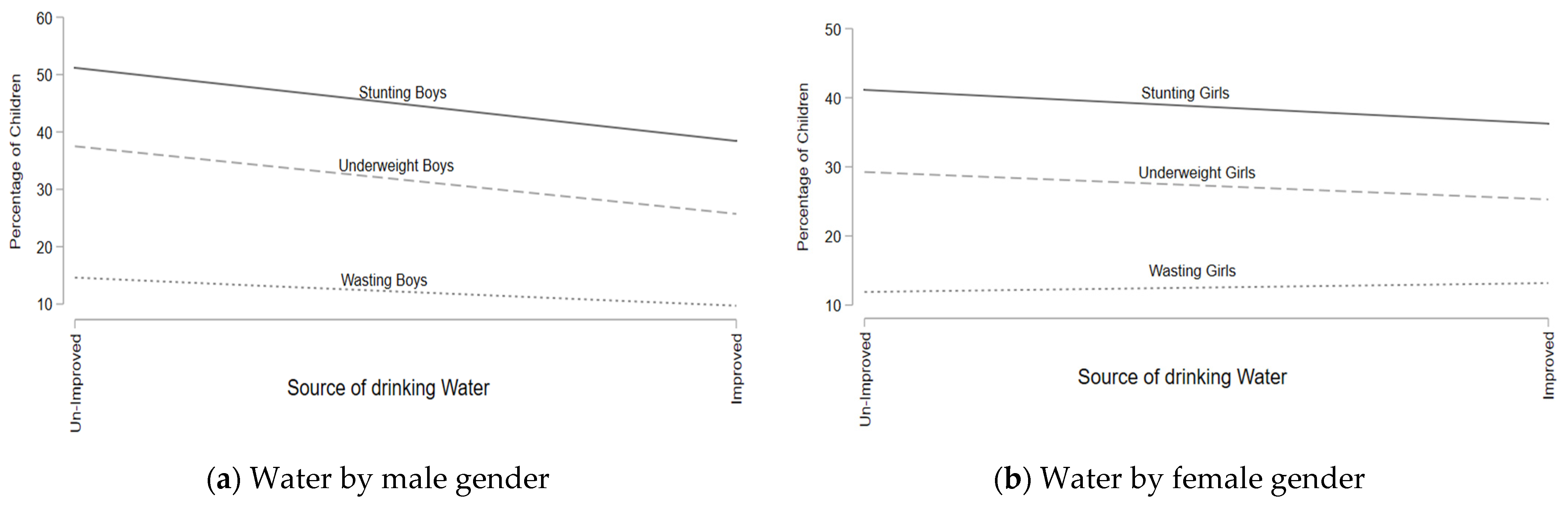

Malnutrition Association with the Water Source and Sanitation Facilities

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fanzo, J.; Hawkes, C.; Udomkesmalee, E.; Afshin, A.; Allemandi, L.; Assery, O.; Baker, P.; Battersby, J.; Bhutta, Z.; Chen, K. Global Nutrition Report 2018: Shining a Light to Spur Action on Nutrition. 2018. Available online: https://globalnutritionreport.org/reports/global-nutrition-report-2018/ (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- World Health Organization. Nutrition Landscape Information System (NLIS) Country Profile Indicators: Interpretation Guide; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241516952 (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Khaliq, A.; Wraith, D.; Miller, Y.; Nambiar-Mann, S. Prevalence, Trends, and Socioeconomic Determinants of Coexisting Forms of Malnutrition Amongst Children under Five Years of Age in Pakistan. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawaregowda, S.K.; Angadi, M.M. Gender differences in nutritional status among under-five children in rural areas of Bijapur district, Karnataka, India. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2015, 2, 506–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dhungana, G.P. Nutritional Status and the Associated Factors in Under Five Years Children of Lamjung, Gorkha and Tanahun Districts of Nepal. Nep. J. Stat. 2017, 1, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ahmad, D.; Afzal, M.; Imtiaz, A. Effect of socioeconomic factors on malnutrition among children in Pakistan. Future Bus. J. 2020, 6, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, I.; Hossain, M.I.; Parvin, M.M.; Saleheen, A.A.S.; Habib, M.J. Gender differences in child nutrition status of Bangladesh: A multinomial modeling approach. J. Humanit. Appl. Soc. Sci. 2021, 4, 1–14. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/JHASS-02-2021-0030/full/html (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Shahid, M.; Qureshi, M.G.; Ahmed, J.F. Socio-economic Causes of Malnutrition among Pre-School Children in Pakistan: A Gender-Disaggregated Analysis. Glob. Eco. Rev. 2020, 5, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babatunde, R.O.; Olagunja, F.I.; Fakayode, S.B.; Sola-Ojo, F.E. Prevalence and Determinants of Malnutrition among under-five children of farming household in Kwara State, Nigeria. J. Agric. Sci. 2011, 3, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayachandran, S.; Kuziemko, I. Why do mothers breastfeed girls less than boys? Evidence and implications for child health in India. Q. J. Econ. 2011, 126, 1485–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, G.M.; Nazir, S.; Satti, M.N.; Farooq, S. Child malnutrition in Pakistan: Trends and determinants. Pak. Inst. Dev. Econ. 2012, 2012, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Heise, L.; Greene, M.E.; Opper, N.; Stavropoulou, M.; Harper, C.; Nascimento, M.; Zewdie, D.; Darmstadt, G.L.; Greene, M.E.; Hawkes, S. Gender inequality and restrictive gender norms: Framing the challenges to health. Lancet 2019, 393, 2440–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubna, N.; Kamalesh, K.P.; Ifeoma, E.U. The prevalence of undernutrition and associated factors among preschool children: Evidence from Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2017–18. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 119, 105579. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid, M.; Liu, Y.; Ameer, W.; Qureshi, M.G.; Ahmed, F.; Tang, K. Comparison of Different Nutritional Screening Approaches and the Determinants of Malnutrition in Under-Five Children in a Marginalized District of Punjab Province, Pakistan. Children 2022, 9, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.; Ameer, W.; Malik, N.I.; Alam, M.B.; Ahmed, F.; Qureshi, M.G.; Zhao, H.; Yang, J.; Zia, S. Distance to Healthcare Facility and Lady Health Workers’ Visits Reduce Malnutrition in under Five Children: A Case Study of a Disadvantaged Rural District in Pakistan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahid, M.; Ahmed, F.; Ameer, W.; Guo, J.; Raza, S.; Fatima, S.; Qureshi, G.M. Prevalence of child malnutrition and household socioeconomic deprivation: A case study of marginalized district in Punjab, Pakistan. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, P.; Bamezai, A.; Subandoro, A.; Ayoya, M.A.; Aguayo, V. Age-appropriate infant and young child feeding practices are associated with child nutrition in India: Insights from nationally representative data. Matern. Child Nutr. 2015, 11, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poda, G.G.; Hsu, C.Y.; Chao, J.C.J. Factors associated with malnutrition among children <5 years old in Burkina Faso: Evidence from the Demographic and Health Surveys IV 2010. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2017, 29, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguayo, V.M.; Badgaiyan, N.; Qadir, S.S.; Bugti, A.N.; Alam, M.M.; Nishtar, N.; Galvin, M. Community management of acute malnutrition (CMAM) programme in Pakistan effectively treats children with uncomplicated severe wasting. Matern. Child Nutr. 2018, 14, e12623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cesare, M.; Bhatti, Z.; Soofi, S.B.; Fortunato, L.; Ezzati, M.; Bhutta, Z.A. Geographical and socioeconomic inequalities in women and children’s nutritional status in Pakistan in 2011: An analysis of data from a nationally representative survey. Lancet 2015, 3, e229–e239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.T.; Magalhães, R.J.S.; Williams, G.M.; Mamun, A.A. Long-term changes in childhood malnutrition are associated with long-term changes in maternal BMI: Evidence from Bangladesh, 1996–2011. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 1121–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, K.; Headey, D.; Singh, A.; Karmacharya, C.; Rana, P.P. Maternal and Child Nutrition in Nepal: Examining drivers of progress from the mid-1990s to 2010s. Glob. Food Secur. 2017, 13, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, O.; Cairncross, S. Can water, sanitation and hygiene help eliminate stunting? Current Evidence and Policy Implications. Matern. Child Nutr. 2016, 12, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngure, F.M.; Reid, B.M.; Humphrey, J.H.; Mbuya, M.N.; Pelto, G.; Stoltzfus, R.J. Water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH), environmental enteropathy, nutrition, and early child development: Making the links. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1308, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, A.; Roy, N. Transitioning toward sustainable development goals: The role of household environment in influencing child health in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia using recent demographic health surveys. Front. Public Health. 2016, 4, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, K.L.; Aguayo, V.M.; Webb, P. Factors associated with wasting among children under five years old in South Asia: Implications for action. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakro, A.N. Water, sanitation and poverty linkages in Pakistan. Asian J. Water Environ. Pollut. 2012, 9, 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Murtaza, F.; Muzaffar, M.; Mustafa, T.; Anwer, J. Water and sanitation risk exposure in children under-five in Pakistan. J. Fam. Community Med. 2021, 28, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee. Guidelines for Integrating Gender-Based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Action: Reducing Risk, Promoting Resilience and Aiding Recovery. 2015. Available online: https://gbvguidelines.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/2015-IASC-Gender-based-Violence-Guidelines_lo-res.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2020).

- Hutton, G.; Whittington, D. Benefits and Costs of the Water Sanitation and Hygiene Targets for the Post-2015 Development Agenda; Copenhagen Consensus Center: Tewksbury, MA, USA, 2015; Available online: http://www.truevaluemetrics.org/DBpdfs/Initiatives/CCC/CCC-water-sanitation-assessment-paper-Guy-Hutton-2015.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2020).

- House, S.; Ferron, S.; Sommer, M.; Cavill, S. Violence, Gender and WASH: A Practitioner’s Toolkit. Making Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Safer through Improved Programming and Services; Wateraid/SHARE: London, UK, 2014; Available online: https://www.susana.org/_resources/documents/default/3-2098-7-1414164920.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2020).

- Akombi, B.J.; Agho, K.E.; Hall, J.J.; Merom, D.; Astell-Burt, T.; Renzaho, A.M.N. Stunting and severe stunting among children under-5 years in Nigeria: A multilevel analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2017, 17, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, T.; Abajobir, A.A.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdulle, A.M.; Abebo, T.A.; Abera, S.F.; Aboyans, V.; et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017, 390, 1211–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinda, P.A.; Genschick, S.; Khayeka-Wandabwa, C.; Kiwanuka-Lubinda, R.; Thilsted, S.H. Dietary diversity determinants and contribution of fifish to maternal and under-fifive nutritional status in Zambia. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.M.; Alam, P.M.; Rawal, L.B.; Chowdhury, S.A.; Murray, J.; Arscott, M.S.; Jack, S.; Hinton, R.; Alam, P.M.; Kuruvilla, S. Cross-country analysis of strategies for achieving progress towards global goals for women’s and children’s health. Bull. World Health Organ. 2016, 94, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheampong, M.; Ejiofor, C.; Salinas-Miranda, A.; Jaward, F.M.; Eduful, M.; Yu, Q. Bridging the under-fifive mortality gap for Africa in the era of sustainable development goals: An ordinary least squares (OLS) analysis. Ann. Glob. Health 2018, 84, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dendup, T.; Zhao, Y.; Dema, D. Factors associated with under-fifive mortality in Bhutan: An analysis of the Bhutan National Health Survey 2012. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Shahid, M. Understanding Food Insecurity Experiences, Dietary Perceptions and Practices in Households Facing Hunger and Malnutrition in Rajanpur District, Pakistan. Pak Perspect. J. 2020, 24, 116–133. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegelbauer, K.; Speich, B.; Mäusezahl, D.; Bos, R.; Keiser, J.; Utzinger, J. Effect of sanitation on soil-transmitted helminth infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO); United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Progress on Household Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene 2000–2020: Five Years into the SDGs; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/progress-on-household-drinking-water-sanitation-and-hygiene-2000-2020/ (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- World Health Organization. Child Growth Standards and the Identification of Severe Acute Malnutrition in Infants and Children: A Joint Statement by the World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund. In WHO Press; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009; Available online: https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/severemalnutrition/9789241598163/en/ (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Victoria, C.G.; Vanghan, J.P.; Kirwood, P.R.; Martinez, J.C.; Barcelos, L.B. Risk factors for malnutrition in Brazilian children: The role of social and environmental variables. Bull. World Health Organ. 1986, 64, 299–309. Available online: https://researchonline.lshtm.ac.uk/id/eprint/4654026/1/bullwho00079-0142.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Victora, C.G.; Huttly, S.R.; Fuchs, S.C.; Olinto, M.T. The role of conceptual frameworks in epidemiological analysis: A hierarchical approach. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1997, 26, 224–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahid, M.; Leghari, I.U.; Ahmed, F. Socio-Economic Correlates of Children’s Nutritional Status: Evidence from Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2017–18. Glob. Eco. Rev. 2020, 1, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M. Interaction of Household Wealth and Women Working Status on Child Malnutrition: Evidence from PDHS-2013. Pak. Perspect. J. 2020, 25, 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Das, S.; Rahman, R.M. Application of ordinal logistic regression analysis in determining risk factors of child malnutrition in Bangladesh. Nutr. J. 2011, 10, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, M.; Lumbert, J. Women and nutrition: Reflection from India and Pakistan. Food Nutr. Bull. 1989, 11, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Shahid, M.; Cao, Y.; Qureshi, M.G.; Zia, S.; Fatima, S.; Guo, J. A Qualitative Exploration in Causes of Water Insecurity Experiences, and Gender and Nutritional Consequences in South-Punjab, Pakistan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, F.; Malik, N.I.; Shahzad, M.; Ahmad, M.; Shahid, M.; Feng, X.L.; Guo, J. Determinants of Infant Young Child Feeding Among Mothers of Malnourished Children in South Punjab, Pakistan: A Qualitative Study. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 834089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, F.; Malik, N.I.; Malik, N.; Qureshi, M.G.; Shahzad, M.; Shahid, M.; Zia, S.; Tang, K. Key Challenges to Optimal Therapeutic Coverage and Maternal Utilization of CMAM Program in Rural Southern Pakistan: A Qualitative Exploratory Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafiq, A.; Hussain, A.; Asif, M.; Hwang, J.; Jameel, A.; Kanwel, S. The effect of “women’s empowerment” on child nutritional status in Pakistan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019, 16, 4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, R.P.; Shrestha, M.L.; Acharya, A.; Upadhaya, N. Determinants of stunting among children aged 0–59 months in Nepal: Findings from Nepal Demographic and Health Survey, 2006, 2011, and 2016. BMC Nutr. 2019, 5, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, S.K.; Hossain, M.B.; Khanam, F.; Akter, F.; Parvez, M.; Yunus, F.M.; Afsana, K.; Rahman, M. Individual-, maternal-and household-level factors associated with stunting among children aged 0–23 months in Bangladesh. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, P.; Rammohan, A.; Gwozdz, W.; Sousa-Poza, A. Changes in child nutrition in India: A decomposition approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019, 16, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irena, A.H.; Mwambazi, M.; Mulenga, V. Diarrhea is a major killer of children with severe acute malnutrition admitted to inpatient set-up in Lusaka, Zambia. Nutr. J. 2011, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chineke, H.N.; Oluoha, R.U.; Uwha, E.P.; Azudialu, B.C.; Nwaigbo, E. The role of family setting in the prevalence of diarrhea diseases in under-five children in Imo State University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria. J. Adv. Med. Med Res. 2017, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalakheti, B.; Panthee, K.; Jain, K.C. Risk factors of diarrhea in children under five years in urban slums. J. Lumbini Med. Coll. 2016, 4, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saheed, R.; Hina, H.; Shahid, M. Water, Sanitation and Malnutrition in Pakistan: Challenge for Sustainable Development. Glob. Pol. Rev. 2021, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalabi, T.E.; Lawal, U.; Ipinlaye, S.J. Prevalence and intensity of genito-urinary schistosomiasis and associated risk factors among junior high school students in two local government areas around Zobe Dam in Katsina State, Nigeria. Parasit. Vectors 2016, 9, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donohue, R.E.; Mashoto, K.O.; Mubyazi, G.M.; Madon, S.; Malecela, M.N.; Michael, E. Biosocial determinants of persistent schistosomiasis among schoolchildren in Tanzania despite repeated treatment. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2017, 2, e61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azupogo, F.; Abizari, A.R.; Aurino, E.; Gelli, A.; Osendarp, S.J.; Bras, H.; Feskens, E.J.M.; Brouwer, I.D. Malnutrition, hypertension risk, and correlates: An analysis of the 2014 ghana demographic and health survey data for 15–19 years adolescent boys and girls. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, K.K.; Story, W.T.; Walser-Kuntz, E.; Zimmerman, M.B. Impact of social capital, harassment of women and girls, and water and sanitation access on premature birth and low infant birth weight in India. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benova, L.; Cumming, O.; Campbell, O.M. Systematic review and meta-analysis: Association between water and sanitation environment and maternal mortality. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2014, 19, 368–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njuguna, J. Progress in sanitation among poor households in Kenya: Evidence from demographic and health surveys. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desalegn, B.B.; Lambert, C.; Riedel, S.; Negese, T.; Biesalski, H.K. Ethiopian orthodox fasting and lactating mothers: Longitudinalstudy on dietary pattern and nutritional status in rural tigray, Ethiopia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Cooten, M.H.; Bilal, S.M.; Gebremedhin, S.; Spigt, M. The association between acute malnutrition and water, sanitation, and hygiene among children aged 6–59 months in rural E thiopia. Matern. Child Nutr. 2019, 15, e12631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.; Cao, Y.; Shahzad, M.; Saheed, R.; Rauf, U.; Qureshi, M.G.; Hasnat, A.; Bibi, A.; Ahmed, F. Socio-economic and environmental determinants of malnutrition in under three children: Evidence from PDHS-2018. Children 2022, 9, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Drinking Water Source | Sanitation/Toilet Facility Type | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Improved | Unimproved | Improved | Unimproved |

| Piped water Piped into lodging Piped water into plot/yard Public tap/standpipe Borehole Tube well water Protected spring Rainwater Protected well Filtration plant | Piped to neighbor Unprotected dug well Protected well Tanker truck Unprotected spring Bottled/sachet water Surface water River/stream/lake/dam/canals/pond Cart with small tank Other unimproved | Flush latrine Flush to pit latrine Flush/pour flush to piped sewer system Flush to septic tank Pit toilet latrine Pit latrine with slab Ventilated improved pit latrine (VIP) Compositing toilet | Pit latrine without a slab or open ditch Bucket toilet Any facility shared with other households Hanging toilet/latrine Flush to somewhere else No facility Facility/stream/field/river/bush Flush, do not know where Other unimproved |

| Variables | Categories | F | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex of Child | Male | 252 | 50.50 |

| Female | 247 | 49.50 | |

| Age of Child (Months) | 0 to 6 | 69 | 13.83 |

| 7 to 12 | 60 | 12.02 | |

| 13 to18 | 62 | 12.42 | |

| 19 to 24 | 81 | 16.23 | |

| 25 to 36 | 227 | 45.49 | |

| Region | Punjab | 49 | 9.82 |

| Sindh | 123 | 24.65 | |

| KPK | 77 | 15.43 | |

| Balochistan | 124 | 24.85 | |

| Gilgit Baltistan | 23 | 4.61 | |

| ICT (Capital) | 14 | 2.81 | |

| AJK | 26 | 5.21 | |

| FATA | 63 | 12.63 | |

| Qualification Level of Mother | Illiterate | 365 | 73.15 |

| Primary | 48 | 9.62 | |

| Middle | 59 | 11.82 | |

| High | 27 | 5.41 | |

| 11–15 | 130 | 26.05 | |

| Greater than 15 | 73 | 14.63 | |

| Wealth Index | Poorest | 189 | 37.88 |

| Poorer | 146 | 29.26 | |

| Middle | 74 | 14.83 | |

| Richer | 52 | 10.42 | |

| Richest | 38 | 7.62 | |

| Source of Drinking Water | Unimproved | 132 | 26.45 |

| Improved | 367 | 73.55 | |

| Had Diarrhea Recently | No | 368 | 73.75 |

| Yes | 131 | 26.25 | |

| Sanitation Facility Type | Unimproved | 181 | 36.27 |

| Improved | 318 | 63.73 |

| Model I | Model II | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Categories | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

| Age of Child (Months) | 0 to 6 months (R) | ||

| 7–12 months | 1.15 (0.56, 2.36) | 1.13 (0.56, 2.25) | |

| 13–18 months | 0.80 (0.39, 1.63) | 1.43 (0.72, 2.84) | |

| 19–24 months | 2.10 ** (1.00, 4.4) | 2.57 *** (1.28, 5.2) | |

| 25–36 months | 1.93 ** (1.00, 4.4) | 3.87 *** (2.2, 6.78) | |

| Region | Punjab (R) | ||

| Sindh | 2.89 *** (1.4, 5.85) | 3.15 *** (1.5, 6.45) | |

| KPK | 1.66 (0.79, 3.47) | 2.07 ** (0.99, 4.29) | |

| Balochistan | 3.03 *** (1.5, 6.33) | 3.44 *** (1.6, 7.47) | |

| Gilgit Baltistan | 0.80 (0.29, 2.24) | 0.97 (0.37, 2.55) | |

| ICT (Capital) | 1.59 (0.56, 4.58) | 0.58 (0.16, 2.07) | |

| AJK | 1.28 (0.44, 3.75) | 1.16 (0.49, 2.77) | |

| FATA | 1.26 (0.54, 2.91) | 1.22 (0.55, 2.72) | |

| Qualification Level of Mother | Illiterate (R) | ||

| Primary | 0.49 ** (0.25, 0.95) | 0.88 (0.45, 1.71) | |

| Middle | 1.03 (0.53, 1.98) | 0.53 ** (0.27, 1.04) | |

| High | 0.35 (0.15, 0.80) | 0.51 (0.23, 1.17) | |

| Wealth Index | Poorest (R) | ||

| Poorer | 0.92 (0.52, 1.65) | 0.83 (0.48, 1.46) | |

| Middle | 0.60 (0.29, 1.26) | 0.92 (0.46, 1.85) | |

| Richer | 0.48 ** (0.22, 1.02) | 0.65 (0.29, 1.47) | |

| Richest | 0.33 *** (0.13, 0.81) | 0.48 * (0.20, 1.13) | |

| Had Diarrhea Recently | No (R) | ||

| Yes | 1.55 * (0.96, 2.50) | 1.48 (0.93, 2.36) | |

| Drinking Water Source | Unimproved (R) | ||

| Improved | 0.62 ** (0.37, 1.03) | 0.80 (0.49, 1.31) | |

| Sanitation Facility | Unimproved (R) | ||

| Improved | 1.24 (0.75, 2.03) | 0.64 ** (0.43, 0.95) | |

| Overall Significance of the Model | |||

| Number of Observations | 497 | 513 | |

| LR Chi2 | 90.42 | 96.57 | |

| Prob > Chi2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.1313 | 0.1359 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saheed, R.; Shahid, M.; Wang, J.; Qureshi, M.G.; Sun, X.; Bibi, A.; Zia, S.; Tang, K. Impact of Drinking Water Source and Sanitation Facility on Malnutrition Prevalence in Children under Three: A Gender-Disaggregated Analysis Using PDHS 2017–18. Children 2022, 9, 1674. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9111674

Saheed R, Shahid M, Wang J, Qureshi MG, Sun X, Bibi A, Zia S, Tang K. Impact of Drinking Water Source and Sanitation Facility on Malnutrition Prevalence in Children under Three: A Gender-Disaggregated Analysis Using PDHS 2017–18. Children. 2022; 9(11):1674. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9111674

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaheed, Rafit, Muhammad Shahid, Jun Wang, Madeeha Gohar Qureshi, Xiaoke Sun, Asma Bibi, Sidra Zia, and Kun Tang. 2022. "Impact of Drinking Water Source and Sanitation Facility on Malnutrition Prevalence in Children under Three: A Gender-Disaggregated Analysis Using PDHS 2017–18" Children 9, no. 11: 1674. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9111674

APA StyleSaheed, R., Shahid, M., Wang, J., Qureshi, M. G., Sun, X., Bibi, A., Zia, S., & Tang, K. (2022). Impact of Drinking Water Source and Sanitation Facility on Malnutrition Prevalence in Children under Three: A Gender-Disaggregated Analysis Using PDHS 2017–18. Children, 9(11), 1674. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9111674