Chest Compression Rates of 90/min versus 180/min during Neonatal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation: A Randomized Controlled Animal Trial

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Randomization

2.2. Sample Size and Power Estimates

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Animal Preparation

2.5. Hemodynamic Parameters

2.6. Respiratory Parameters

2.7. Automated Chest Compression Machine

2.8. Force Measurement

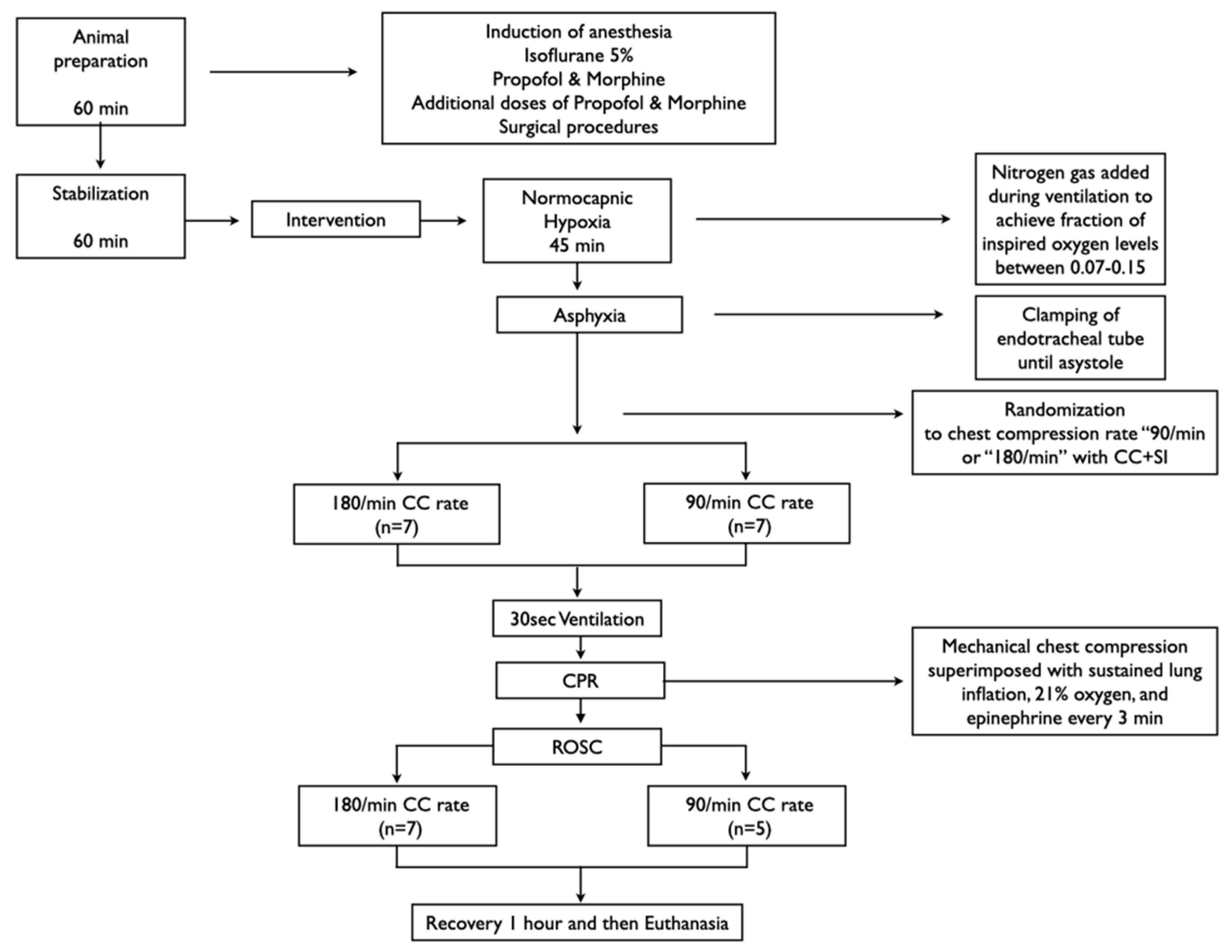

2.9. Experimental Protocol

2.10. Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Resuscitation and Primary Outcome

3.2. Hemodynamic Parameters

3.3. Respiratory Parameters

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| CC | Chest compression |

| CC + SI | Continuous chest compressions during sustained inflations |

| CPR | Cardiopulmonary resuscitation |

| CO | Cardiac output |

| C:V ratio | Compression to ventilation ratio |

| ROSC | Return of spontaneous circulation |

References

- Aziz, K.; Lee, H.C.; Escobedo, M.B.; Hoover, A.V.; Kamath-Rayne, B.D.; Kapadia, V.S.; Magid, D.J.; Niermeyer, S.; Schmölzer, G.M.; Szyld, E.; et al. Part 5: Neonatal Resuscitation: 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation 2020, 142, S524–S550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyckoff, M.H.; Wyllie, J.P.; Aziz, K.; de Almeida, M.F.; Fabres, J.; Fawke, J.; Guinsburg, R.; Hosono, S.; Isayama, T.; Kapadia, V.S.; et al. Neonatal Life Support: 2020 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment Recommendations. Circulation 2020, 142, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babbs, C.; Meyer, A.; Nadkarni, V. Neonatal CPR: Room at the top—A mathematical study of optimal chest compression frequency versus body size. Resuscitation 2009, 80, 1280–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schmölzer, G.M. Chest Compressions during Sustained Inflation during Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Newborn Infants Translating Evidence from Animal Studies to the Bedside. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2019, 4, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmölzer, G.M.; O’Reilly, M.; LaBossiere, J.; Lee, T.-F.; Cowan, S.; Qin, S.; Bigam, D.L.; Cheung, P.-Y. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation with chest compressions during sustained inflations: A new technique of neonatal resuscitation that improves recovery and survival in a neonatal porcine model. Circulation 2013, 128, 2495–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, E.S.; Cheung, P.-Y.; Lee, T.-F.; Lu, M.; O’Reilly, M.; Schmölzer, G.M. Return of spontaneous Circulation Is not Affected by Different Chest Compression Rates Superimposed with Sustained Inflations during Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Newborn Piglets. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, E.S.; Görens, I.; Cheung, P.-Y.; Lee, T.-F.; Lu, M.; O’Reilly, M.; Schmölzer, G.M. Chest Compressions during Sustained Inflations Improve Recovery when Compared to a 3:1 Compression:Ventilation Ratio during Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in a Neonatal Porcine Model of Asphyxia. Neonatology 2017, 112, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilkenny, C.; Altman, D.G.; Browne, W.J.; Cuthill, I.C.; Emerson, M. Improving Bioscience Research Reporting: The ARRIVE Guidelines for Reporting Animal Research. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2010, 8, e1000412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Cheung, P.-Y.; Li, E.S.; Lee, T.-F.; Lu, M.; O’Reilly, M.; Olischar, M.; Schmölzer, G.M. Effects of epinephrine on hemodynamic changes during cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a neonatal piglet model. Pediatr. Res. 2018, 83, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schmölzer, G.M.; Kamlin, C.O.F.; Dawson, J.A.; te Pas, A.B.; Morley, C.J.; Davis, P.G. Respiratory monitoring of neonatal resuscitation. Arch. Dis. Child.-Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2010, 95, F295–F303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Os, S.; Cheung, P.; Pichler, G.; Aziz, K.; O’Reilly, M.; Schmölzer, G.M. Exhaled carbon dioxide can be used to guide respiratory support in the delivery room. Acta Paediatr. 2014, 103, 796–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruckner, M.; Kim, S.Y.; Shim, G.H.; Neset, M.; Garcia-Hidalgo, C.; Lee, T.F.; O’Reilly, M.; Cheung, P.Y.; Schmölzer, G.M. Assessment of optimal chest compression depth during neonatal cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A randomised controlled animal trial. Arch. Dis. Child.-Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2022, 107, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruckner, M.; O’Reilly, M.; Lee, T.-F.; Neset, M.; Cheung, P.Y.; Schmölzer, G.M. Effects of varying chest compression depths on carotid blood flow and blood pressure in asphyxiated piglets. Arch. Dis. Child.-Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2021, 106, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Hidalgo, C.; Solevåg, A.; Kim, S.Y.; Shim, G.H.; Cheung, P.-Y.; Lee, T.-F.; O’Reilly, M.; Schmölzer, G.M. Sustained inflation with 21% versus 100% oxygen during cardiopulmonary resuscitation of asphyxiated newborn piglets-A randomized controlled animal study. Resuscitation 2020, 155, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Hidalgo, C.; Cheung, P.-Y.; Vento, M.; Solevåg, A.L.; O’Reilly, M.; Saugstad, O.; Schmölzer, G.M. A Review of Oxygen Use During Chest Compressions in Newborns—A Meta-Analysis of Animal Data. Front. Pediatr. 2018, 6, S196–S197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Solevåg, A.; Lee, T.-F.; Lu, M.; Schmölzer, G.M.; Cheung, P.-Y. Tidal volume delivery during continuous chest compressions and sustained inflation. Arch. Dis. Child.-Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2017, 102, F85–F87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, G.-H.; Kim, S.Y.; Cheung, P.-Y.; Lee, T.-F.; O’Reilly, M.; Schmölzer, G.M. Effects of sustained inflation pressure during neonatal cardiopulmonary resuscitation of asphyxiated piglets. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustofa, J.; Cheung, P.-Y.; Patel, S.; Lee, T.-F.; Lu, M.; Pasquin, M.P.; O’Reilly, M.; Schmölzer, G.M. Effects of different durations of sustained inflation during cardiopulmonary resuscitation on return of spontaneous circulation and hemodynamic recovery in severely asphyxiated piglets. Resuscitation 2018, 129, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaran, D.; Vali, P.; Chandrasekharan, P.; Chen, P.; Gugino, S.F.; Koenigsknecht, C.; Helman, J.; Nair, J.; Mathew, B.; Rawat, M.; et al. Effect of a Larger Flush Volume on Bioavailability and Efficacy of Umbilical Venous Epinephrine during Neonatal Resuscitation in Ovine Asphyxial Arrest. Children 2021, 8, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sankaran, D.; Chandrasekharan, P.K.; Gugino, S.F.; Koenigsknecht, C.; Helman, J.; Nair, J.; Mathew, B.; Rawat, M.; Vali, P.; Nielsen, L.; et al. Randomised trial of epinephrine dose and flush volume in term newborn lambs. Arch. Dis. Child.-Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2021, 106, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, K.R.; Babbs, C.F.; Frissora, H.A.; Davis, R.W.; Silver, D.I. Cardiac output during cardiopulmonary resuscitation at various compression rates and durations. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 1981, 241, H442–H448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vrancken, S.L.; Heijst AF van de Boode, W.P. Neonatal Hemodynamics: From Developmental Physiology to Comprehensive Monitoring. Front. Pediatr. 2018, 6, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patel, S.; Cheung, P.-Y.; Lee, T.-F.; Pasquin, M.P.; Lu, M.; O’Reilly, M.; Schmölzer, G.M. Asynchronous ventilation at 120 compared with 90 or 100 compressions per minute improves haemodynamic recovery in asphyxiated newborn piglets. Arch. Dis. Child.-Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2020, 105, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vali, P.; Lesneski, A.; Hardie, M.; Alhassen, Z.; Chen, P.; Joudi, H.; Sankaran, D.; Lakshminrusimha, S. Continuous chest compressions with asynchronous ventilations increase carotid blood flow in the perinatal asphyxiated lamb model. Pediatr. Res. 2021, 90, 752–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruckner, M.; Neset, M.; O’Reilly, M.; Lee, T.-F.; Cheung, P.-Y.; Schmölzer, G.M. Haemodynamic changes with varying chest compression rates in asphyxiated piglets. Arch. Dis. Child.-Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boldingh, A.M.; Jensen, T.H.; Bjørbekk, A.T.; Solevåg, A.L.; Nakstad, B. Rescuers’ physical fatigue with different chest compression to ventilation methods during simulated infant cardiopulmonary resuscitation. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015, 29, 3202–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, E.S.; Cheung, P.-Y.; O’Reilly, M.; Aziz, K.; Schmölzer, G.M. Rescuer fatigue during simulated neonatal cardiopulmonary resuscitation. J. Perinatol. 2015, 35, 142–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| CC Rate 90/min (n = 7) | CC Rate 180/min (n = 7) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | |||

| Age (days) | 2 (1–3) | 3 (1–3) | 0.81 |

| Weight (kg) | 2.2 (2.0–2.4) | 2.0 (1.9–2.2) | 0.21 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 144 (142–159) | 140 (131–168) | 0.86 |

| Mean Arterial blood pressure (mmHg) | 53 (52–61) | 57 (50–62) | 0.82 |

| Carotid flow (mL/min) | 36 (34–51) | 31 (20–37) | 0.18 |

| Cerebral oxygenation (%) | 32 (32–41) | 36 (34–45) | 0.20 |

| pH | 7.47 (7.46–7.51) | 7.51 (7.48–7.52) | 0.12 |

| PaO2 (torr) | 62 (61–90) | 62 (55–71) | 0.46 |

| PaO2 (torr) | 36.3 (35.0–38.9) | 37.4 (34.1–40.0) | 0.94 |

| Base excess (mmol/L) | 3 (2–4) | 4 (3–7) | 0.17 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 3.6 (2.5–4.2) | 2.6 (2.5–3.1) | 0.37 |

| Duration of asphyxia (s) | 440 (280–506) | 470 (360–585) | 0.65 |

| Characteristics at commencement of Resuscitation | |||

| Heart rate (bpm) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | |

| Carotid blood flow (mL/min) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | |

| Arterial pH | 6.58 (6.54–6.68) | 6.55 (6.50–6.73) | 0.46 |

| paCO2 (torr) | 102 (67–121) | 106 (86–112) | 0.68 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 16 (16–19) | 19 (17–20) | 0.13 |

| Base Excess (mmol/L) | −29 (−30–−26) | −28 (−30–−22) | 0.65 |

| Characteristics immediately after return of spontaneous circulation | |||

| Heart rate (bpm) | 180 (165–212) | 204 (182–248) | 0.21 |

| Carotid blood flow (mL/min) | 23 (21–30) | 20 (16–23) | 0.12 |

| Arterial pH | 6.78 (6.52–6.84) | 6.78 (6.74–6.96) | 0.54 |

| paCO2 (torr) | 50 (39–73) | 52 (40–58) | 0.43 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 20 (18–20) | 20 (20–20) | 0.36 |

| Base Excess (mmol/L) | −28 (−30–−26) | −26 (−29–−25) | 0.38 |

| Characteristics 30 min after return of spontaneous circulation | |||

| Heart rate (bpm) | 190 (152–219) | 206 (192–241) | 0.19 |

| Carotid blood flow (mL/min) | 29 (25–39) | 33 (18–39) | 0.87 |

| Arterial pH | 7.02 (6.93–7.19) | 7.12 (6.97–7.24) | 0.65 |

| paCO2 (torr) | 37 (33–57) | 33 (28–44) | 0.64 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 16 (14–19) | 17 (16–19) | 0.47 |

| Base Excess (mmol/L) | −20 (−23–−15) | −20 (−23–−17) | 0.79 |

| CC Rate 90/min (n = 7) | CC Rate 180/min (n = 7) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tidal volume (mL/kg) | 5.8 (0.9) | 5.3 (1.4) | 0.477 |

| Minute Ventilation (mL/kg/min) | 522 (79) | 945 (248) | 0.003 |

| Peak Inspiratory Flow (L/min) | 3.7 (0.4) | 5.8 (0.9) | 0.0007 |

| Peak Expiration Flow (L/min) | −5.8 (0.7) | −8.0 (0.7) | 0.0009 |

| Peak Inflation Pressure (cmH2O) | 30.0 (1.5) | 31.1 (4.2) | 0.546 |

| Positive End Expiratory Pressure (cmH2O) | 29.1 (2.0) | 30.2 (5.1) | 0.625 |

| End-tidal CO2 (mmHg) | 18 (7) | 23 (15) | 0.248 |

| Rate (/min) * | 90 (1) | 179 (1) | <0.0001 |

| CC Rate 90/min (n = 7) | CC Rate 180/min (n = 7) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n = 2) | Female (n = 5) | p Value | Male (n = 3) | Female (n = 4) | p Value | |

| Asphyxia time (s) # | 399 (198–600) | 440 (313–501) | 1.00 | 430 (360–585) | 481 (365–573) | 0.86 |

| Achieving ROSC (n) | 1 (50%) | 3 (60%) | 1.00 | 3 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 1.00 |

| ROSC time (s) # | 395 (189–600) | 136 (88–600) | 0.57 | 79 (73–118) | 137 (95–290) | 0.23 |

| Requiring epinephrine (n) | 2 (100%) | 3 (60%) | 1.00 | 0 (0%) | 2 (50%) | 0.43 |

| Epinephrine doses # | 2 (1–3) | 1 (0–3) | 0.57 | 0 (0–0) | 0.5 (0–2) | 0.40 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bruckner, M.; Neset, M.; Garcia-Hidalgo, C.; Lee, T.-F.; O’Reilly, M.; Cheung, P.-Y.; Schmölzer, G.M. Chest Compression Rates of 90/min versus 180/min during Neonatal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation: A Randomized Controlled Animal Trial. Children 2022, 9, 1838. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9121838

Bruckner M, Neset M, Garcia-Hidalgo C, Lee T-F, O’Reilly M, Cheung P-Y, Schmölzer GM. Chest Compression Rates of 90/min versus 180/min during Neonatal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation: A Randomized Controlled Animal Trial. Children. 2022; 9(12):1838. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9121838

Chicago/Turabian StyleBruckner, Marlies, Mattias Neset, Catalina Garcia-Hidalgo, Tze-Fun Lee, Megan O’Reilly, Po-Yin Cheung, and Georg M. Schmölzer. 2022. "Chest Compression Rates of 90/min versus 180/min during Neonatal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation: A Randomized Controlled Animal Trial" Children 9, no. 12: 1838. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9121838

APA StyleBruckner, M., Neset, M., Garcia-Hidalgo, C., Lee, T.-F., O’Reilly, M., Cheung, P.-Y., & Schmölzer, G. M. (2022). Chest Compression Rates of 90/min versus 180/min during Neonatal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation: A Randomized Controlled Animal Trial. Children, 9(12), 1838. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9121838