Abstract

Social media tools are increasingly used in child’s language and literacy development in early years. However, few researchers shed light on effectiveness and the practice that the EC professionals and teachers have adopted in ECE settings and other related contexts. This scoping review synthesized and evaluated the literature on social media integration in language and literacy development in ECE in the last decade, to provide a clearer picture on what social media tools were used, how they were used, and whether they were effective. Results showed that a wide-range of social media tools were used in diverse learning activities; however, few studies designed the learning activities with the guidance of an evidence-based teaching method or pedagogical framework.

1. Introduction

Web 2.0 refers to a perceived second generation of the Internet where users can create content, share, interact, and collaborate; it emphasizes a participatory culture among Internet users [1,2]. Compared with Web 1.0 where Internet users can only passively view content, Web 2.0 brings benefits of efficient multi-way communication among Internet users [2,3]. Supported by Web 2.0, social media are “interactive technologies that facilitate the creation and sharing of information, ideas, interests, and other forms of expression through virtual communities and networks” [4].

In recent years, social media Web 2.0 tools are increasingly used in language and literacy instruction (e.g., [1,5]). while also gaining momentum in early childhood education (ECE) [6]. ECE here refers to the care and education of children from birth to eight [7]. Although scholars have explored the use of social media in literacy practices and instructions in ECE [8,9,10], there is limited empirical evidence regarding the effectiveness of using social media on children’s language and literacy development. This scoping review will analyze and synthesize studies on using social media tools to support language and literacy development in early childhood education, and to demystify the characteristics of social media tools that are currently used in language and literacy development for young children; clarify the ways they are used; and, most importantly, synthesize evidence on their effectiveness.

1.1. Digital Technology in ECE

Although ECE has not been quick in taking advantage of the ubiquitous presence of [11] digital technologies [8], a variety of digital technologies have been used in ECE [12,13]. Some of the major technologies that are gaining momentum in ECE include e-books (e.g., [14,15,16], games (e.g. [17,18]), AI technologies (e.g. [18,19]), and mobile touchscreen technologies (e.g. [20,21]). Many of these technologies can be social media Web 2.0 tools or have social media features. For instance, e-book platforms that allow online sharing, collaboration, and interaction among the readers are social media Web 2.0 tools [22,23]. Online games in which players can communicate, collaborate, and interact with each other are also social media tools, such as Minecraft (education edition) [3]. Touchscreen mobile devices or tablets are often used in combination with applications. Lynch and Redpath [24] classified apps by their openness and closedness. Whereas closed apps follow a behaviorist approach to skill instruction by rewarding correct answers, open apps allow children to be creators and direct their own activities; open apps also allow connections to other apps or sharing of children’s creations [24]. All social media apps are open apps, but not all open apps are social media apps because allowing connections with other apps or sharing does not necessarily mean users can engage in online interactions in the app. It can be seen that a lot of knowledge about social media Web 2.0 tools adoption in ECE is masked under studies of tablets, games, e-books, or digital technologies in general.

However, social interaction is an important function and benefit that media Web 2.0 tools bring to early years education. Without social interaction and resource sharing, learning will not have any meaningful relationships among children [12]. In addition, children instinctively need to interact with others in meaningful ways and share what they have learned [25]. Therefore, social media is well-positioned to satisfy children’s needs to interact with others and share their learning with people potentially across the globe. Thus, there is an urgent need to comb through existing studies and synthesize available evidence on the use of social media Web 2.0 tools in language and literacy development in ECE, to shed light on the potential unique ways of utilizing social media for early childhood education.

1.2. Social Media Web 2.0 Tools in ECE

In early years, social media Web 2.0 tools have been most frequently used for parent–school communication; scholars found social media to be an efficient, flexible, and effective way to increase parental involvement, enhance mutual understanding and build partnerships between families and schools [8,26,27,28,29]. Meanwhile, social media Web 2.0 tools have also been used sporadically to assist young children’s learning and development in a variety of domains, such as media education [30], math learning [31], music education [32], health promotion [33,34], connected learning [35], higher order thinking skills [36], physical activities [6], and social competence [37]. However, these studies tend to focus on describing the practices and perceived benefits and challenges, with limited rigorous evidence given on actual gains in child learning and development. In addition, language and literacy development is particularly suitable for adopting social media Web 2.0 tools. This is because social media Web 2.0 tools enable children to communicate with real audiences in authentic tasks, so children can have a meaningful purpose for their literacy practices. The back-and-forth communications with audiences on social media platforms also give children motivations and directions for improving their language use and deepen their understanding of the functions of language [38]. Therefore, it is important to have a special focus on how researchers and educators have used social media Web 2.0 tools to promote language and literacy development in ECE.

1.3. Social Media in Language and Literacy Development in ECE

Many existing studies explored how social media Web 2.0 tools are used in language learning among older populations including upper primary school, secondary schools, and particularly college and adult learners [1,5]. Less studies have been conducted in early childhood. Before Web 2.0 was coined by O’Reilly in 2004, text-based technologies were the dominant technology used in language learning [1]. However, when using web 2.0-based social media tools in language learning, there is greater diversity in the type of tools involved. In Wang and Va ’squez’s [1] review, social text publishing tools including blogs and wikis were used in 58% of the studies.

When investigating social media integration in language and literacy development in ECE, scholars have primarily focused on describing how teachers used social media tools to structure their literacy instruction or play-based classrooms [8,10,39,40,41,42]. While some scholars zoomed in on one classroom to provide a rich description [8,39,41], others have intentionally explored multiple cases to illustrate the complexity around the digital transformation of early literacy instruction [10,40,42]. While most studies explored the learning of a dominant language, Peterson [41] explored using Skype to increase preschoolers’ opportunities to participate in minority language activities beyond school borders in a multilingual context.

In the home context, scholars have explored how social media was used to maintain heritage language [43,44,45] or to facilitate digital play to enrich literacy learning opportunities [46,47]. Scholars were also interested in deconstructing young children’s digital text creation process; using case studies, they examined how young children utilized digital resources for text production and the type of semiotic resources and strategies employed by the children [9,47].

After the outbreak of COVID-19, scholars have also paid particular attention to how social media Web 2.0 tools can be used to provide virtual learning opportunities [48,49]. These studies focused on describing teachers’ practices during virtual learning sessions, and often did not distinguish between practices that were used for language and literacy development and practices for child learning and development in other domains.

Overall, the existing research provided very rich descriptions and in-depth understandings of how social media tools were utilized to facilitate language and literacy development both in school and in the home in formal and non-formal learning. However, these studies tend to be case studies or used small samples; there is a lack of a more comprehensive picture on how social media tools are used to facilitate language and literacy development in young children, particularly given the complexity of digital transformation in different pedagogical contexts found in the literature [10]. More importantly, previous research had not focused on analyzing the effects of such practices on children’s language and literacy skills. Limited research is known about whether the diverse social media-mediated language and literacy learning practices could really lead to gains in children’s language and literacy skills.

This scoping review provides critical information for early childhood educators and researchers on the use of social media in language and literacy development, and its effectiveness. This review will shed light on enhancing practice and evaluation of social media tool integration in early childhood language and literacy development.

1.4. Research Objectives and Questions

This review aims to evaluate, synthesize, and display the latest literature on using social media tools to support language and literacy development in ECE settings. It is intended to analyze and present information on the research design, social media tools used, learning activities involved, and effects of social media integration on language and literacy development of young children in ECE settings. To achieve these objectives, we focused on studies that examined the application of social media tools to support language and literacy development in ECE. In addition, this study puts forward possible pathways for future research on social media tools in ECE, hoping to establish a strong theoretical basis and clarify challenges that might hinder the effective application of social media tools in ECE.

This review is guided by the following research questions (RQs):

RQ1: What social media tools were used to support language and literacy development in ECE?

RQ2: How were social media tools used to support language and literacy development in ECE?

RQ3: What were the effects of using social media tools on language and literacy development in ECE?

RQ4: What were the research methods used in studies that examined the implementation of social media tools in language and literacy development in ECE?

2. Methods

The methodology of this scoping review follows the framework established by Arksey and O’Malley [50], and Levac et al. [51]. This scoping review went through a five-stage process involving identifying research questions, identifying relevant studies, study selection, data charting, and reporting results.

2.1. Information Sources and Search Strategies

The electronic databases used for the literature search included Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), Web of Science, EBSCO, Psych-Info, Medline, and PubMed. Search terms were discussed among the research team and used in combination: (child OR infant * OR “early child *” OR “early years” OR toddler OR preschool *) AND (educator OR teacher OR mentor) AND (play * OR interact * OR converse * OR language OR talk OR communicate * OR cooperate *) AND (digital technology OR social media * OR Web 2.0 OR digital tools OR high technology *). The search was limited to peer-reviewed journal articles in English that were published from January 2012 to mid-2022 when the search was conducted. All articles were accessed from July to August 2022.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Table 1 below outlines the inclusion and exclusion criteria applied in study selection.

Table 1.

Criteria for inclusion and exclusion.

2.3. Study Selection

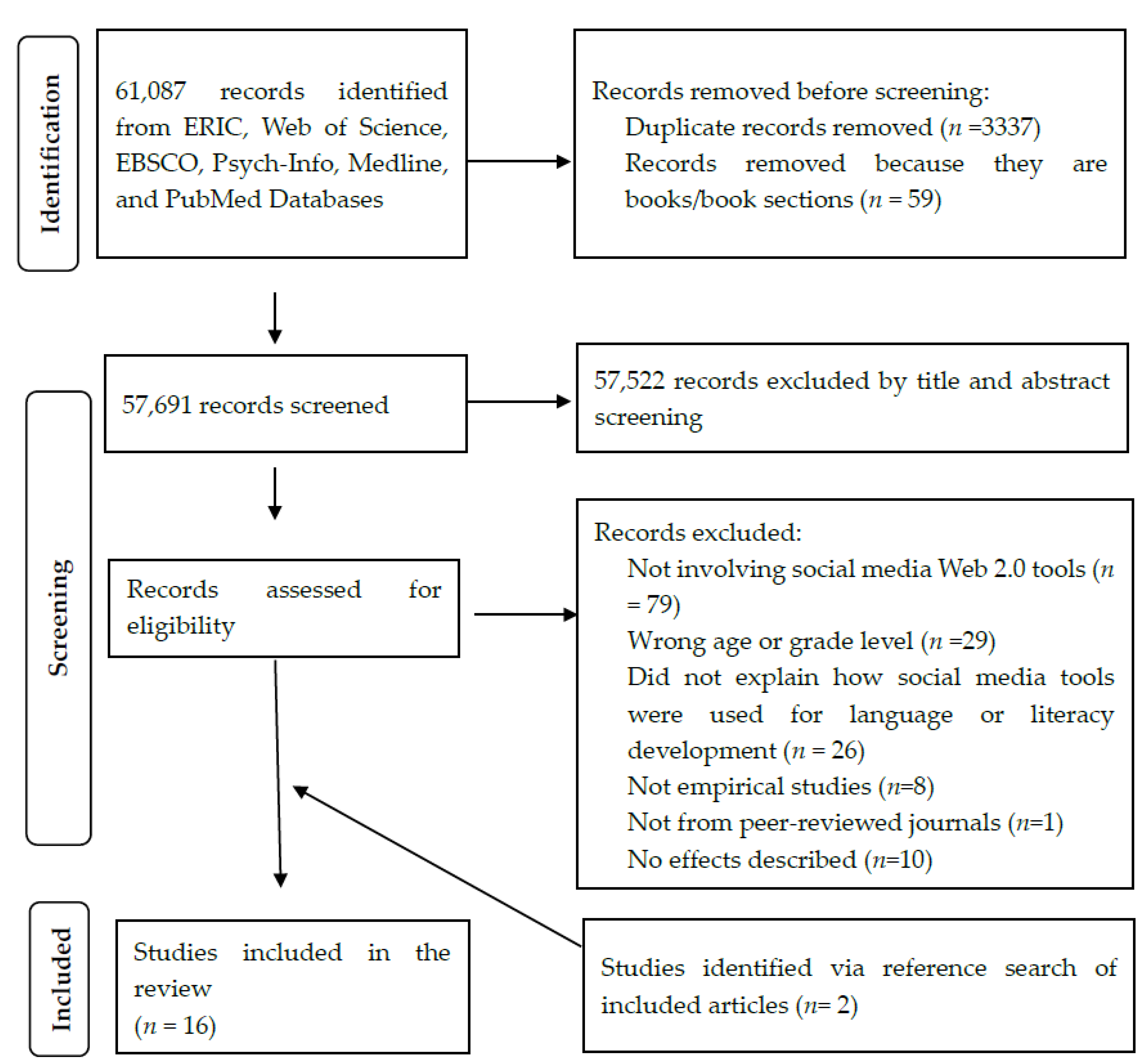

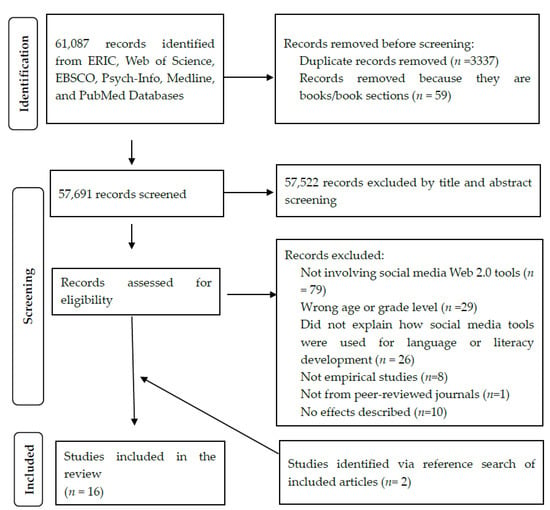

As shown in Figure 1, a total of 61,087 records were found using our search strategy. A total of 1348 articles were found on Web of Science, 357 on PubMed, 288 on Medline (searched via EBSCO), 767 on Psych-Info (searched via EBSCO), 54,253 on ERIC, 4074 on EBSCO. Overall, 3337 duplicates were identified and removed using Endnote 20’s duplicate detection function. Articles were removed because: (1) they were not relevant to the research topic based on title and abstract (n = 57523); (2) they did not involve social media Web 2.0 tools (n = 79); (3) children examined in the study were of wrong age or grade level (n = 29); (4) they did not explicitly explain how social media tools were used for language and literacy development (n = 25); (5) they were not empirical studies (n = 8); (6) they were not from peer-reviewed journals (n = 1); (7) they did not provide evidence on the impact of using social media on language and literacy development (n = 10). We also searched the references of the included studies and some relevant literature review studies and identified another two articles for inclusion. Inconsistencies between the co-authors in the study selection process were resolved through discussion. In total, 16 studies were thoroughly examined in this review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram of included articles in the scoping review.

2.4. Analysis

Title, keywords, and the main text of the included studies were used for the analysis. The co-authors generated the coding scheme and an excel-based data extraction chart in discussion. Then, data extraction was carried out by the primary researcher independently while the second author audited the data charting results.

3. Results

Despite its importance, the topic of social media tools integration in language and literacy development in ECE is under-studied; only 16 studies could be identified in this review. Among the 16 studies, 8 were conducted in the USA. The rest were conducted mostly in developed countries including Sweden (2 studies), Greece, UK, and Canada (1 study). Furthermore, in Brazil, Turkey and China, there was one study completed in each county. Twelve studies were conducted in the school setting [25,38,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61] while four studies examined the home setting [62,63,64,65]. In particular, three studies actually emphasized home–school collaboration. Dore at al. [52] examined a virtual summer kindergarten readiness program during the COVID-19 pandemic. Meanwhile, both Snell et al. [64] and Olszewski and Cullen-Conway [65] used social media tools to provide parents with instructions on home literacy activities, and then proceeded to evaluate the effectiveness of such practices on children’s emergent literacy development. More basic characteristics of the included studies including research aims, research design, participants, instruments, and target language are available in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies.

3.1. What Social Media Tools Were Used to Support Language and Literacy Development in ECE?

There is great diversity in the social media tools employed by the included studies. The 16 included studies employed 17 different social media tools. The only Web 2.0 tools that were used by more than one study were Google Docs and Twitter. Because of the diversity of the individual social media tools included, it might be beneficial to analyze what type of social media tools they represented. [3] provided a classification of social media tools; it outlined 14 social media types defined by the common characteristics of the social media tools that fell under each type.

Text publishing tools refers to tools primarily used for publishing texts such as stories, essays, conversations, and even presentation slides [3]. Text publishing tools were most frequently utilized by the included studies (n = 7). For instance, Weblog Typepad was a class blog created by the teacher for students to post writings and exchange comments [38]. Another example was ePearl which was a web-based digital portfolio tool which mainly provided the students with a text editor and an audio recorder to write down and share their ideas; however, students could also upload other file formats including images, photos, slideshows, etc. [58]. Interpersonal social media tools are tools for interpersonal communication online [3]. It was the second most frequently used type of social media (n = 5). For instance, online video chat services including Skype, Zoom, and Facetime had all been utilized in included studies. Productivity tools, which were defined as tools to enhance the organization’s productivity, were the third most often used type (n = 2). For example, Google Docs is a cloud-based word processor that allows online collaboration [55,56], while Google Slides is a cloud-based slide editor that allows collaboration and online presentation [60]. Audio publishing tools are tools primarily used for publishing and sharing audio segments [3]. For example, Papa is an audio publishing app where users can create and share audio files or music of up to 6 min long; the app also allows other users to leave an audio comment [61]. Audio publishing tools appeared in two studies while microblogging tools (Twitter) also appeared in two studies. Social gaming tools (Minecraft) were only used in one study. Table 3 provides a full list of the social media tools included, their key features, the social media type that each tool represents, and web links to official sites, if available.

Table 3.

An overview of the social media tools used in the included studies.

Among all the social media tools included, five could also count as mobile social media tools as they either operate entirely as a mobile app (e.g., Book Creator app) or their mobile app version was used (e.g., Showme app). Other social media types were not found in the included studies, including social communities, photo publishing tools, video publishing tools, live casting tools, virtual world tools, really simple syndication, and aggregators. Please note that one social media tool could fall into multiple classifications, as social media tools today continuously expand their functionalities; not to mention that Van Looy’s [3] classification was not mutually exclusive.

While almost all studies used different social media tools, three studies used more than one social media tool. Snell et al [64] intentionally gave teachers freedom in choosing the app they preferred. Genlott and Grnlund [56] used different social media tools to achieve different purposes; whereas Google Docs was used for collaborative writing and providing formative feedback on work-in-progress, Google Sites was used to publish the final product to a wider audience for final comments. In Miller [25], both social media apps were used to share students’ work, but Showme app allowed students to create and share voice-over presentations with the same app on their own, while the teacher shared links to student work regularly on the class Twitter account.

3.2. How Were Social Media Tools Used to Support Language and Literacy Development in ECE?

We explore this research question from four perspectives: first or second language, dominant or minority language, specific language and literacy skill targeted, and learning activities involved.

Most studies used social media tools to support the learning of the dominant language in the country where the study was conducted. Among them, the dominant language was the first language of the children in eight studies [53,55,56,58,59,60,62,65]. Two studies examined a mixture of first-language learners and second language learners [52,64], while two studies focused on second language learners who were trying to acquire the dominant language [25,38].

Social media tools were used to support the learning of the minority language, in the context where the study took place, in two studies. While Eubanks et al [54] examined a Chinese immersion program in the school setting, Szecsi & Szilagyi [63] examined how social media was used to maintain heritage language at home. In two other studies, social media tools were used to support the acquisition of English as a foreign language in Turkey and China [57,61].

Writing was the most often targeted skill (nine studies) when integrating social media tools into literacy instruction, followed by reading (six studies), vocabulary (six studies), speaking (three studies), story comprehension (two studies), listening (two studies), narrative skill (two studies), letter knowledge (one study), phonological awareness (one study), reflective skill (one study), and print awareness (one study). One study did not report on a particular literacy skill as its target learning domain [25].

Social media tools were integrated into diverse learning activities. In the school context, the most common learning activity type involves the creation of digital texts or digital artefacts and sharing them online. Students might learn to write different genres by writing and publishing on social media platforms [38,55,56]; they might also be invited to document and reflect on their learning, including class activities, project findings, or homework assignments either via a single digital artefact or via an e-portfolio [25,58,59,60,61]. They might also create and publish a multimodal digital story [54]. Although sharing via online publishing is a unique feature of social media, social media can also allow online collaborations. However, only two studies intentionally utilized the online collaboration features of social media tools [55,56].

The Ellison and Drew [53] study was unique in that Minecraft was used to help students visualize what they would write about. During the COVID-19 pandemic, social media tools were also used to conduct online synchronized lessons both between the teacher and the child, and between the teacher and the parent [52]. In two studies, students not only used social media platforms for teacher-initiated learning activities, but also voluntarily created digital artefacts and texts and posted on the social media platforms [58,59].

Among the studies in the school context, only four studies reported a clear framework behind their pedagogical design. Genlott and Grnlund [55,56] used sociocultural theory to guide their pedagogical design of the Write to Learn method which used social media to enable collaborative writing, formative assessment, and formative feedback among peers. The 2013 study was a pilot of the 2016 study and the pedagogical design was refined in the 2016 study. The study by Eubanks et al. [54] used a pedagogy of multiliteracies and incorporated the three communication modes (interpretive, interpersonal, presentational) specified in the Standards for Foreign Language Learnings in the US as a design framework for its 21st century Chinese language writing workshop. Finally, the social media platform used in the study by Lysenko and Abrami [58] was designed under the theoretical framework of self-regulated learning. When using the platform, students would follow the steps of self-regulated learning including setting goals, completing the activity, and writing reflections.

When used in the home context, social media tools were often used for virtual story-time [52,62,63] or for providing parents instructions on literacy practices at home [64,65]. Dialogic reading was the only evidence-supported method that some of these programs reported to have employed [62,65]. For a full list of learning activities that were implemented using social media tools in the included studies, please refer to Table 4.

Table 4.

Application of social media tools in language and literacy development.

3.3. What Were the Effects of Using Social Media Tools on Language and Literacy Development in ECE?

As shown in Table 5, although all of the included studies explicitly reported on the impact of using social media tools in language and literacy development, only 11 studies measured the effects of integrating social media tools on language and literacy skills of young children, and the results were largely mixed [52,53,54,55,56,58,59,61,62,64,65]. Literacy instructions incorporating social media tools were found to have positive effects on young children’s alphabet knowledge, vocabulary, speaking fluency, story comprehension, reading skills including reading comprehension, and writing skills [52,54,55,56,58,61,64,65]. Several case studies or qualitative studies also provided some evidence on the positive impact of literacy instruction using social media tools, on children’s language and literacy development. However, these were mostly accounts based on teachers’ and parents’ perceptions or based on teachers’ or the researchers’ subjective evaluation of students’ written work, without providing very clear information on the evaluation standards and procedures used [25,38,57,60,63]. Among all the types of social media tools that were used in the included studies, productivity tools were consistently associated with improvements in children’s language and literacy skills [55,56,60]. Additionally, the productivity tools used all belonged to Google Apps for Education. Text publishing tools were also consistently associated with enhancements in children’s language and literacy skills across studies [38,54,57,58]. Although Lysenko and Abrami [58] only found positive effects on vocabulary, reading comprehension, and written expression, they did not find this on listening comprehension. The only exception was the Silvia de Oliveira et al. [59] study where evidence of the impact on language and literacy skills was inconclusive. Similarly, microblogging tools were reported to have a positive impact in both studies that utilized this type of tool [25,65]. However, in the Olszewski and Cullen-Conway [65] study, the positive impact was only found on vocabulary and story comprehension, but not on print knowledge. The findings related to interpersonal social media tools were more mixed. While most studies reported positive effects on a selected range of language and literacy skills among all the skills they assessed [52,63,64], Gaudreau et al. [62] actually found no differences in students’ reading comprehension among the groups that used social media tools and the groups that did not use such tools. Audio publishing tools had a positive impact on children’s speaking fluency but were only utilized in one study [61]. So, productivity tools, text publishing tools, and microblogging tools seem to be the types of social media tools that were more consistently associated with improvements in young children’s language and literacy skills.

Table 5.

Effects of integrating social media tools on language and literacy development.

3.4. What Were the Research Methods Used in Studies That Examined the Implementation of Social Media Tools in Language and Literacy Development in ECE?

This section outlines a summary of the research methods used in the studies that examined the integration of social media tools in language and literacy development in ECE.

Quasi-experimental design was most frequently employed (six studies) but studies varied with regards to the inclusion of control groups and pretests. The pretest posttest with non-equivalent groups design was used by three studies [55,58,61]. Two studies did not include a control group [52,65] while Genlott and Grönlund [56] switched to a design with a control group but no pretest because this time they used the National Standard Literacy Test in Sweden to measure literacy skills; the test could only be taken by 3rd graders while their intervention started in 1st grade.

Case study and multi-case study was the second most frequently (four studies) used research design [38,53,59,60]. Triangulation of data sources can be found in most of the case studies. For instance, Silvia de Oliveira et al. [59] used observation, child assessment, and analysis of student-created digital artefacts to examine the changes in students’ reading and writing practices after receiving a laptop with internet access. Theodosiadou and Konstantinidis [60] also used a mixed-methods data collection method including a parent questionnaire, teacher interviews, and analysis of students’ writing samples to examine the impact of e-portfolio on learning in a Greek primary school. Other case studies only collected qualitative data, but still used more than one source of data; the most commonly used sources of data include observations, interviews, and students’ work samples [38,53].

Three studies employed a qualitative research design; data collection was conducted by interview [57] or teachers’ narrative accounts [25], or a combination of interview and auto-ethnographic interview [63]. Two studies used randomized experiments [62,64] and one additional study used a mixed-methods design and collected data via observation, surveys, and audio-visual materials [54].

4. Discussion

Social media has been increasingly used in ECE, particularly in children’s language and literacy development. Scholars have extensively described how social media tools are used in literacy instruction in the school and literacy practices at home. However, little evidence-based research showed the extent to which young children’s language and literacy skills were gained when social media tools were adopted. To address this gap, this article provides a scoping review of studies on integrating social media tools into language and literacy development in early childhood, focusing on the features of social media tools used, implementation of social media tools in literacy learning activities, program effectiveness, and study design. Despite the limited number of empirical studies that explicitly provided evidence on the impact of integrating social media in language and literacy development in early childhood, new insights were gained from the existing references into what and how social media tools were used in the language and literacy development of young children, and their effectiveness. Moreover, addressing the important issue of integrating social media tools in language and literacy development in ECE generates new opportunities for understanding how to best utilize social media tools to support young children’s language and literacy development, and the benefits it might bring to children’s linguistic development.

This scoping review showed that very few studies provided evidence on the impact of social media use on language and literacy development in early childhood, and on children’s language and literacy outcomes. Merely 16 studies could be identified. Most of the studies were conducted in developed countries except for the three studies that took place in Turkey, Brazil, and China. Future studies could focus more on developing countries, as young children from less developed regions may also benefit from the use of social media in early childhood education.

This review has showcased a variety of social media tools that were utilized for language and literacy development in early childhood. A total of 17 different tools were used in 16 studies with only Google Docs and Twitter appearing in more than 1 study. Although previous studies have provided some guidelines on choosing educational apps for preschoolers, especially apps designed for literacy development [66,67,68], the apps they evaluated were not all social media tools, and not all social media tools are apps. Therefore, the framework for evaluation of apps provided by these studies may not necessarily address the unique strengths of social media tools in ECE, or cover the non-app-based social media tools. Future studies should evaluate and compare the strengths and weaknesses of these social media tools and develop a framework for choosing social media Web 2.0 tools for language and literacy in ECE, to ease the selection by practitioners, caregivers, and researchers.

Among the various social media types identified by Van Looy [3], five out of the seventeen tools examined were mobile social media tools. This is consistent with the increasing trend of using touchscreen mobile devices in ECE [20]. Text-publishing tools, interpersonal social media tools, and productivity tools were the top three most prevalently found social media tool types in the included studies. Audio publishing tools, microblogging tools, and social gaming tools were also present but with a lower frequency. The included studies did not experiment with social communities, photo publishing tools, video publishing tools, live casting tools, virtual world tools, Really Simple Syndication, and aggregators. However, these types of social media tools also boast great potential for language and literacy development. For instance, previous studies have found positive effects in using Facebook, a social community tool, to enhance language and literacy skills in adult learners and even students with dyslexia [69,70]. Both live casting tools and virtual world tools can facilitate remote literacy learning as the COVID-19 pandemic continues, and the virtual world tools such as Second Life can create a more immersive experience than regular interpersonal social media tools such as Skype. YouTube, a video publishing tool with Really Simple Syndication functions, has also been used to facilitate heritage language maintenance and digital play out of school [44,46]. Future studies should examine the effects of using these less-studied social media tool types, on language and literacy development in early childhood.

Among the various types of social media tools utilized in the included studies, productivity tools, text publishing tools, and microblogging tools are the types of social media tools that were more consistently associated with improvements in young children’s language and literacy knowledge and skills. However, this finding should be interpreted with caution for two reasons. First, some types of social media tools such as the audio publishing tools were only used in one study; therefore, there were simply not sufficient amounts of evidence to draw conclusions on whether audio publishing tools can be consistently associated with language and literacy skill improvements. Second, the number and type of language and literacy knowledge and skills assessed varied across studies. When studies assessed more diverse knowledge and skills, they were more likely to find positive effects to be restricted to a selected range of knowledge and skills, compared to studies that only assessed one type of language and literacy skill. Therefore, future studies should further examine the less-studied social media tools, echoing the point above. Future studies should also measure a wider range of language and literacy knowledge and skills.

Social media tools were used for both first and second language acquisitions and both dominant and minority language acquisitions. Only two studies examined foreign language acquisition [57,61]. Yet, previous studies have found social media to be effective for foreign language learning among upper-primary, secondary, and college level learners, as it enables learners to go beyond borders [1,5]. Future studies should explore more on the use of social media tools for foreign language learning in the context of ECE.

Writing and reading were the most often targeted language skills when using social media for language and literacy learning for young children. This review revealed that learning activities that involved social media tools were diverse. Social media was most frequently used for creating and publishing digital texts and artefacts. By publishing children’s digital creations online to a wider audience, teachers were able to provide the students with an authentic and meaningful purpose for their creations [38]. This was a main purpose for social media integration in literacy instruction among the included studies and a reason why reading and writing skills were the most often targeted skills. However, this does not mean that other emergent literacy skills could not be improved with the help of social media. More studies on how social media tools may be used to develop other emergent literacy skills, is warranted in future studies. Moreover, the wider audience was carefully selected to be composed of only other students, teachers, and families, thereby creating a safe online interaction environment for the children while fostering better family–home connections [25,38]. Future studies might want to compare the effects of different audience composition on language and literacy development when using social media tools.

Among all the included studies, only six studies had a theoretical framework for pedagogical design that informed their learning activities. When integrating digital technologies in ECE, paying too much attention to the tools over the pedagogy can be a problem [7]. Future studies should pay closer attention to pedagogical design.

Most studies employed a quasi-experimental design, followed by case study design, qualitative design, randomized experiment, and mixed-methods design. The study samples were also relatively small in most studies. Thus, it is unclear whether the findings were generalizable to other populations and contexts. Future studies should consider following Genlott and Grönlund’s [55,56] example to first rigorously test the effectiveness of a social media integrated pedagogy in a smaller sample, and then validate the results with larger samples.

Moreover, out of the 16 studies included, only 11 studies measured the language and literacy skills of the children after using social media to support language and literacy development, and the results were mixed. Several studies did not use instruments that were rigorously designed and validated [53,54,55]; in some studies, the data were not rigorously analyzed [54,59]. The other five studies only used parental perceptions, teacher perceptions, or teachers’ and researchers’ subjective evaluations as evidence for the positive impact on literacy development, while providing very limited information on the evaluation procedures and standards followed [25,57,60,63]. This will necessarily make any positive findings less convincing. Future work should provide more empirical evaluations of the effects of social media integration in language and literacy development in early childhood and consider using psychometrically sound measurements to assess child outcomes, and to better guide future practice.

4.1. Limitations and Contributions

This scoping review can inform future research in advancing social media tool selection, research design, assessment of language and literacy skills, learning activity design when incorporating social media tools in the language, and literacy instruction in early childhood. It can also provide researchers and practitioners with some guidance on the design, implementation, and evaluation of age-appropriate social media tools for young children. However, this scoping review is exploratory in nature, given the small number of eligible studies on the research topic of social media integration in early childhood language and literacy development. Therefore, more advanced techniques such as meta-analysis and systematic review were not used. Several included studies were focused on tablet use, digital play, or general information and computer technology (ICT) integration. They did not provide detailed descriptions of the functionalities of the apps or technological tools incorporated in their study. The authors had to manually check the official websites of these tools and determine whether such tools are social media tools based on the definitions provided in this study. In addition, this study only explored journal articles published in peer-reviewed journals, and did not incorporate grey literature, books, and organizational reports. Thus, some social media tools, or studies that employed social media tools, may have been excluded from this study. Finally, this study only included studies published in English; thus, studies published in other languages may have been neglected. Future researchers should organize multi-cultural teams to examine publications in more diverse languages. Nevertheless, this scoping review could provide valuable directions for integrating social media and Web 2.0 tools in early childhood education and serve as a reference for future research on technology integration in ECE.

4.2. Future Research Direction

Most of the included studies were conducted in Western contexts except Sun et al. [61]. Moreover, first-language learning was more often examined than second-language acquisition and more studies used social media tools to support dominant language acquisition rather than minority language learning. Using a culturally responsive approach to language learning in early childhood warrants the examination of more contexts, more second language learners, and more minority language learning in future studies.

In several studies, multiple social media tools were used together [56] or social media tools were used in combination with other technologies such as mobile applications that are not social media, e-book platforms without social media features, and interactive whiteboards [54,58,59]. Future studies should compare and contrast the pedagogical affordances provided by different combinations of social media tools with additional social media tools, or other non-social media technologies commonly found in early childhood classrooms.

Among the studies that used social media in school settings, four studies used social media tools to create homework assignments or project assignments that extended the learning beyond the classroom [57,58,59,61]. Future studies could compare the effectiveness of integrating social media tools in class activities, versus using it to extend learning beyond the classroom.

Young children in the included studies also exhibited improvements in reflections on their learning. While some researchers chose tools or pedagogical designs that could intentionally foster self-regulated learning abilities in young children [58,60], other researchers also witnessed children’s voluntary reflections on their learning [59]. Future studies could analyze how self-regulated learning is fostered as a byproduct of social media integration in literacy instruction, and whether the enhanced self-regulated learning ability of young children further contributes to gains in language and literacy skills.

In this review, only four studies examined using social media tools for language and literacy development in the home context, and three of them provided rigorous evidence for impact on language and literacy skills [62,64,65]. However, there are additional previous studies that examined social media integration in language and literacy practices at home, without assessing its impact on child learning [44,45,46,47]. Future studies could provide more evidence on the impact of using social media at home on language and literacy development of young children.

4.3. Implications for Policy and Practice

Although a limited number of studies measured the impact of social media integration on young children’s language and literacy skills, they did find social media tool integration in language and literacy instruction to have positive effects on young children’s alphabet knowledge, vocabulary, speaking fluency, story comprehension, reading skills (including reading comprehension), and writing skill [52,54,55,56,58,61,64,65]. Moreover, they also reported improved students’ attitudes towards writing [54], learning engagement and confidence in creative writing [53], and motivation and commitment [60]. Therefore, social media integration in language and literacy instruction in early years should be promoted at both fronts of policy and practice.

When teachers devise their own ways to integrate social media into language and literacy instructions, teachers should also devise indicators of child progress to guide the refinement of the practice. Policymakers and researchers could invent rigorous and easy-to-use evaluation tools that can help teachers better gauge the effectiveness of their self-invented practices. Although evidence on effectiveness of these practices is not consistently rigorous across studies currently, there are some pedagogies that have been rigorously developed and validated such as the Write to Learn method [55,56]. Teachers could also adapt such practices for their own teaching instead of devising something new.

There are a variety of social media tools but not all of them are available in multiple regions, or multiple languages, or on all types of devices. This review is not meant to recommend a specific social media tool to teachers; rather, it aims to help teachers understand the types of social media tools available and what learning activities they enable children to engage in. When choosing social media tools for instruction, teachers should first clarify their purposes for social media tool integration and then determine which specific social media tool best serves their instructional purposes. It might be necessary to combine multiple social media tools or combine social media tools with other technologies, just like several studies did to achieve the instructional purposes [54,58,59].

Moreover, social media integration can be effectively implemented without achieving one tablet/laptop per child [38,56]. This knowledge has particularly important implications for early childhood educators in less developed countries/regions and socioeconomically disadvantaged populations.

Finally, several studies found that the use of social media tools in literacy instruction effectively improved parental involvement and parent–school communication [25,38,64]. So, using social media in literacy instruction in early years can promote mutual understanding between the school and the parents, and contribute to a school–family partnership model in early childhood education and care.

5. Conclusions

Social media tools are increasingly incorporated into language and literacy development in ECE settings. However, limited evidence is available on whether such practices are effective at achieving their goals: enhancing young children’s language, and literacy development. This review synthesized and evaluated the most updated literature on social media integration in language and literacy development in ECE to provide a clearer picture on what social media tools were used, how they were used, and whether they were effective. Results showed that a wide-range of social media tools were used in diverse learning activities; however, few studies designed the learning activities with the guidance of an evidence-based teaching method or pedagogical framework. Moreover, existing studies presented mixed findings on whether social media integration was effective in enhancing young children’s language and literacy development. Only eight out of the sixteen studies included provided evidence of positive effect. More importantly, most studies were fraught with methodological difficulties, including the lack of rigorously designed and validated instruments, evaluation procedures, evaluation standards, and rigorous data analysis methods, thus making the positive findings less convincing. To advance the research and practice on social media tool integration in language and literacy development in ECE settings, more rigorous evaluations of the effectiveness of social media tool integration are necessary, and the results of such evaluations should be used to guide the design of evidence-based learning activities both at home and in school.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z. and J.L.; methodology, Y.Z.; software, Y.Z.; validation, Y.Z., J.L.; formal analysis, Y.Z.; investigation, Y.R.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, S.W.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University RDF, number: RDF-21-01-009. The APC was funded by Y. Zhao.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University (protocol code RDF-21-01-009 on 25th January 2022.)

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data could be obtained upon request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, S.; Va’squez, C. Web 2.0 and second language learning: What does the research tell us? CALICO J. 2012, 29, 412–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Web 2.0. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Web_2.0 (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Van Looy, A. Social Media Management: Technologies and Strategies for Creating Business Value; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-21990-5. [Google Scholar]

- Social Media. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_media (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Istifci, I.; Doğan Ucar, A. A review of research on the use of social media in language teaching and learning. J. Educ. Technol. Online Learn. 2021, 4, 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J. Exploring the adoption of social media in self-paced physical activity in early childhood education: A case in central China. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2022, 70, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, J.; Yang, W.; Li, H. A scoping review of studies on coding curriculum in early childhood: Investigating its design, implementation, and evaluation. J. Res. Child. Educ. 2022, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantozzi, V.B. “It’s everyone’s iPad”: Tablet use in a play-based preschool classroom. J. Early Child. Res. 2021, 19, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kervin, L.; Mantei, J. Digital storytelling: Capturing children’s participation in preschool activities. Literacy 2016, 26, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofkova Hashemi, S.; Cederlund, K. Making room for the transformation of literacy instruction in the digital classroom. J. Early Child. Lit. 2017, 17, 221–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, M.M. Using tablets and apps to enhance emergent literacy skills in young children. Early Child. Res. Q. 2018, 42, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C. Young children’s use of ICT in Shanghai preschools. Asia-Pac. J. Res. 2016, 10, 97–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, G.H.; Hu, X.; Yang, W. Digital technology use and early reading abilities among bilingual children in Singapore. Policy Futures Educ. 2021, 19, 242–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Roberts, A.C.; Bus, A. Bilingual children’s visual attention while reading digital picture books and story retelling. J. Exp. Child. Psychol. 2022, 215, 105327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roskos, K.A.; Sullivan, S.; Simpson, D.; Zuzolo, N. E-Books in the early literacy environment: Is there added value for vocabulary development? J. Res. Child. Educ. 2016, 30, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bus, A.G.; Takacs, Z.K.; Kegel, C.A.T. Affordances and limitations of electronic storybooks for young children’s emergent literacy. Dev. Rev. 2015, 35, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertala, P. Fun and games—Finnish children’s ideas for the use of digital media in preschool. Nord. J. Digit. Lit. 2016, 11, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troseth, G.L.; Russo, C.E.; Strouse, G.A. What’s next for research on young children’s interactive media? J. Child. Media 2016, 10, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Yang, W. Artificial intelligence in early childhood education: A scoping review. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2022, 3, 100049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.C.; Hwang, G.J. Roles and research trends of touchscreen mobile devices in early childhood education: Review of journal publications from 2010 to 2019 based on the technology-enhanced learning model. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 30, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, M.M. Parent scaffolding of young children’s use of touch screen tablets. Early Child Dev. Care. 2018, 188, 1652–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-M.; Liang, T.-H.; Su, Y.-N.; Chen, N.-S. Empowering personalized learning with an interactive e-book learning system for elementary school students. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2012, 60, 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafini, F.; Youngs, S. Reading workshop 2.0: Children’s literature in the digital age. Read. Teach. 2013, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, J.; Redpath, T. ‘Smart’ technologies in early years literacy education: A meta-narrative of paradigmatic tensions in iPad use in an Australian preparatory classroom. J. Early Child. Lit. 2014, 14, 147–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.J. Technologies in the classroom: Advancing English language acquisition. Kappa Delta Pi Rec. 2018, 54, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, G.; Toe, D. ‘Parents don’t need to come to school to be engaged:’ Teachers use of social media for family engagement. Educ. Action Res. 2021, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanca, L.-N.; Cristina, Z.-Y.; José Luis, L. Uses of digital mediation in the school-families relationship during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchholz, B.A.; Riley, S. Mobile documentation: Making the learning process visible to families. Read. Teach. 2020, 74, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.J.; Rivera-Vernazza, D.E. Communicating digitally: Building preschool teacher-parent partnerships via digital technologies during COVID-19. Early Child. Educ. J 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Li, X. Arts teachers’ media and digital literacy in kindergarten: A case study on Finnish and Chinese children using a shared blog in early childhood education. Int. J. Digit. Lit. Digit. Competence 2015, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, M.M.; Hargis, J.; Appelgate, M.H. What a “tweet” idea! Teach. Child. Math. 2017, 24, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koops, L.H. ’Now can I watch my video?’: Exploring musical play through video sharing and social networking in an early childhood music class. Res. Stud. Music Educ. 2012, 34, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, I.H.; Schwendler, T.; Trude, A.C.B.; Anderson Steeves, E.T.; Cheskin, L.J.; Lange, S.; Gittelsohn, J. Implementation of text-messaging and social media strategies in a multilevel childhood obesity prevention intervention: Process evaluation results. Inquiry-J. Health Car. 2018, 55, 46958018779189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swindle, T.M.; Ward, W.L.; Whiteside-Mansell, L. Facebook: The use of social media to engage parents in a preschool obesity prevention curriculum. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartiainen, H.; Leinonen, T.; Nissinen, S. Connected learning with media tools in kindergarten: An illustrative case. EMI Educ. Media. 2019, 56, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawilinski, L. HOT blogging: A framework for blogging to promote higher order thinking. Read. Teach. 2009, 62, 650–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.W.; Berson, I.R.; Berson, M.J.; Han, S. Young chinese children’s remote peer interactions and social competence de-velopment during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2022, 54, S48–S64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.-s. Web 2.0 tools and academic literacy development in a US urban school: A case study of a second-grade English language learner. Lang. Educ. 2014, 28, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantozzi, V.B.; Johnson, C.; Scherfen, A. One classroom, one iPad, many stories. Read. Teach. 2018, 71, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.-H.; Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A.T.; Ding, A.-C.; Glazewski, K. Experienced iPad-using early childhood teachers: Practices in the one-to-one iPad classroom. Comput. Sch. 2017, 34, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, P. Beyond borders-Digital tablets as a resource for pre-school children’s communication in a minority language. Des. Learn. 2018, 10, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.B.; Handler, L.K.; FitzPatrick, E.; Whittingham, C.E. The device in the room: Technology’s role in third grade literacy instruction. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2020, 52, 515–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedra, J. Virtual proximity and transnational familyhood: A case study of the digital communication practices of poles living in Finland. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2021, 42, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, F.F.S. ’Ba-SKY-aP’ with her each day at dinner’: Technology as supporter in the learning and management of home languages. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2021, 42, 747–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Flewitt, R. Young Chinese Immigrant Children’s Language and Literacy Practices on Social Media: A Translanguaging Perspective. Lang. Educ. 2020, 34, 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kervin, L. Powerful and playful literacy learning with digital technologies. Aust. J. Lang. Lit. 2016, 39, 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kervin, L.; Comber, B. Digital writing from the start to the end: Creating a book for a friend. Theory Pract. 2021, 60, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolopoulou, K. Online education in early primary years: Teachers’ practices and experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szente, J. Live virtual sessions with toddlers and preschoolers amid COVID-19: Implications for early childhood teacher education. J. Technol. Teach. Educ. 2020, 28, 373–380. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dore, R.; Justice, L.; Mills, A.K.; Narui, M.; Welch, K. Virtual kindergarten readiness programming for preschool-aged children: Feasibility, social validity, and preliminary impacts. Early Educ. Dev. 2021, 32, 903–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, M.; Drew, C. Using digital sandbox gaming to improve creativity within boys’ writing. J. Res. Child. Educ. 2020, 34, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eubanks, J.-F.; Yeh, H.-T.; Tseng, H. Learning Chinese through a twenty-first century writing workshop with the integration of mobile technology in a language immersion elementary school. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2018, 31, 346–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genlott, A.A.; Grönlund, Å. Improving literacy skills through learning reading by writing: The iWTR method presented and tested. Comput. Educ. 2013, 67, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genlott, A.A.; Grönlund, Å. Closing the gaps—Improving literacy and mathematics by ict-enhanced collaboration. Comput. Educ. 2016, 99, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaynar, N.; Sadik, O.; Boichuk, E. Technology in early childhood education: Electronic books for improving students’ literacy skills. TechTrends Link. Res. Pract. Improv. Learn. 2020, 64, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysenko, L.V.; Abrami, P.C. Promoting reading comprehension with the use of technology. Comput. Educ. 2014, 75, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia de Oliveira, K.; Marie Jane Soares, C.; Juliano de Vargas, B. One laptop per child and its implications for the process of written language learning: A case study in Brazil. Rev. Electrónica Investig. Educ. 2013, 15, 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Theodosiadou, D.; Konstantinidis, A. Introducing E-Portfolio use to primary school pupils: Response, benefits and challenges. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Innov. Pract. 2015, 14, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Lin, C.-H.; You, J.; Shen, H.j.; Qi, S.; Luo, L. Improving the English-speaking skills of young learners through mobile social networking. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2017, 30, 304–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudreau, C.; King, Y.A.; Dore, R.A.; Puttre, H.; Nichols, D.; Hirsh-Pasek, K.; Golinkoff, R.M. Preschoolers benefit equally from video chat, pseudo-contingent video, and live book reading: Implications for storytime during the coronavirus pandemic and beyond. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szecsi, T.; Szilagyi, J. Immigrant Hungarian families’ perceptions of new media technologies in the transmission of heritage language and culture. Lang. Cult. Curric. 2012, 25, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snell, E.K.; Wasik, B.A.; Hindman, A.H. Text to talk: Effects of a home-school vocabulary texting intervention on prekindergarten vocabulary. Early Child. Res. Q. 2022, 60, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszewski, A.; Cullen-Conway, M. Social media accompanying reading together: A smart approach to promote literacy engagement. Read. Writ. Q. 2021, 37, 479–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riojas-Cortez, M.; Montemayor, A.; Leveridge, T. Choosing the right app for preschoolers: Challenges and solutions. Child. Educ. 2019, 95, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chik, A. English language teaching apps: Positioning parents and young learners. Chang. Engl. Stud. Cult. Educ. 2014, 21, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, M.M.; Wang, Y.; Qi, G.Y.; Neumann, D.L. An evaluation of mandarin learning apps designed for English speaking pre-schoolers. J. Interact. Learn. Res. 2019, 30, 167–193. [Google Scholar]

- AlSaleem, B.I. The effect of Facebook activities on enhancing oral communication skills for EFL learners. Int. Educ. Stud. 2018, 11, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Barden, O. ‘…If we were cavemen we’d be fine’: Facebook as a catalyst for critical literacy learning by dyslexic sixth-form students. Literacy 2012, 46, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).