Robotic Anxiety—Parents’ Perception of Robot-Assisted Pediatric Surgery

Abstract

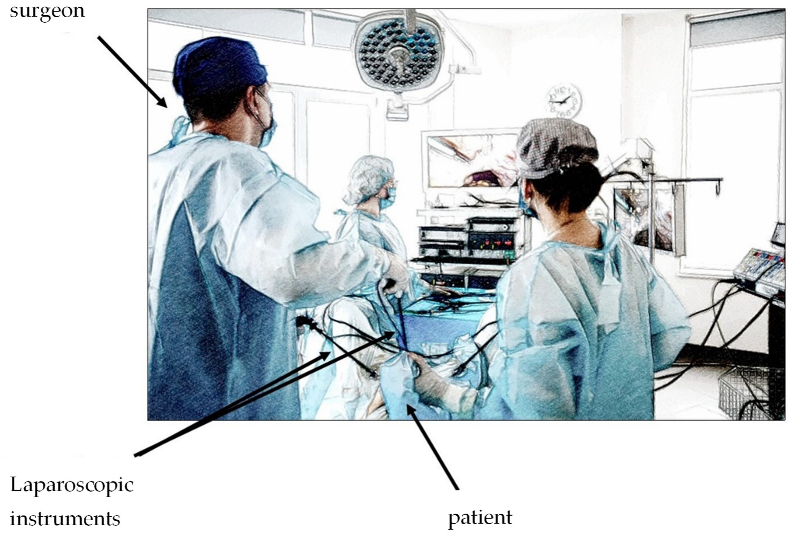

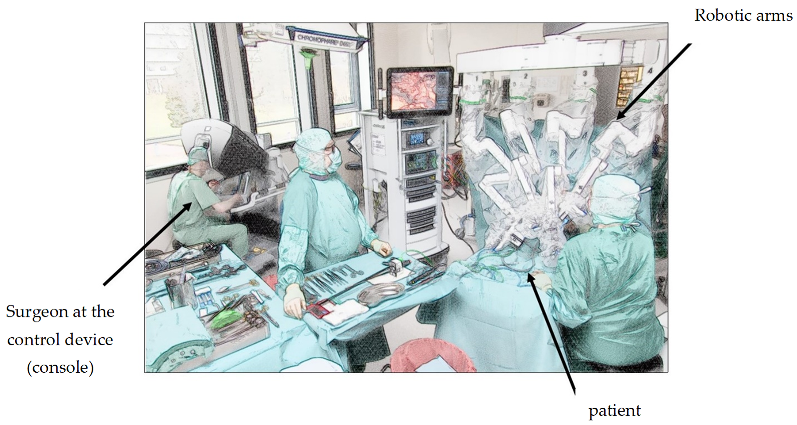

:1. Introduction

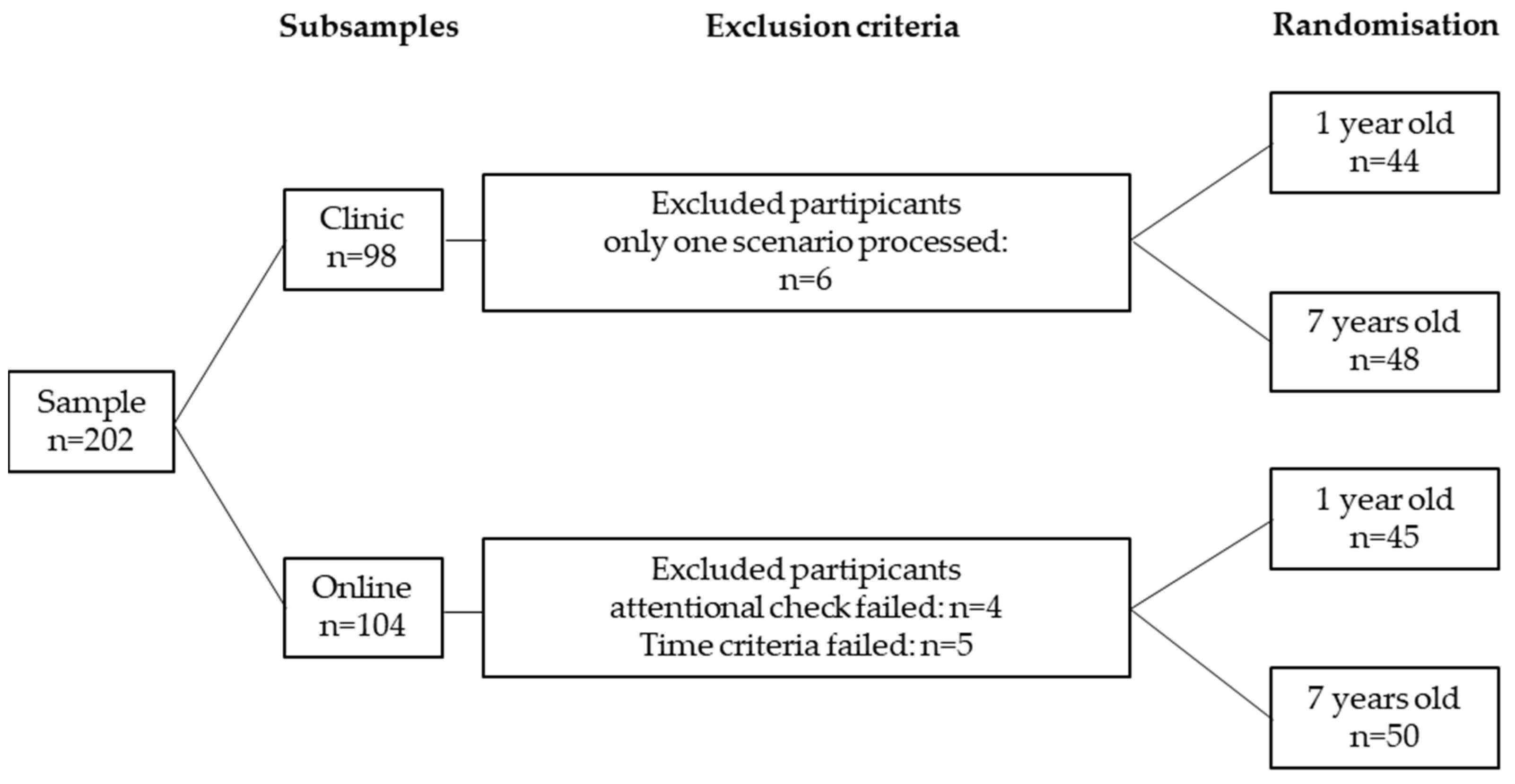

2. Methods and Materials

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire in English Translation

- Questionnaire

- Please select only one answer for each question.

- Questions about robot-assisted surgery

| Do Not Agree at All | Do Not Agree | Neither | Agree | Fully Agree | |

| I am familiar with robot-assisted surgery. | |||||

| I have a lot of knowledge about robot-assisted surgery | |||||

| I know more about robot-assisted surgery than the average person. |

- Technology questions

| Do Not Agree at All | Do Not Agree | Neither | Agree | Fully Agree | |

| Technical progress is good for mankind. | |||||

| Technology enables people to live comfortably. | |||||

| Technology is more of a threat than an advantage to people. | |||||

| Technology restricts people in their personal freedom. | |||||

| Technical devices are often opaque and difficult for me to control. | |||||

| I like to try out new technical devices. |

- Questions about laparoscopic surgery

| Do Not Agree at All | Do Not Agree | Neither | Agree | Fully Agree | |

| I am familiar with laparoscopic surgery. | |||||

| I have a lot of knowledge about laparoscopic surgery. | |||||

| I know more about laparoscopic surgery than the average person. |

- Scenario part 1

- Please put yourself in the position described as best you can and answer the following questions regarding your 1-year-old’s laparoscopic surgery for ureteral stenosis.

| 0 Not at All | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 Very Strong | |

| I feel angry. | |||||||||||

| I feel anxious. | |||||||||||

| I feel happy. | |||||||||||

| I feel disgusted. | |||||||||||

| I feel surprised. | |||||||||||

| I feel sad. |

| Do Not Agree at All | Do Not Agree | Neither | Agree | Fully Agree | |

| In this situation, I would expect long-term negative consequences for my child (e.g., irreversible damage, follow-up surgery). | |||||

| In this situation, I would be willing to let my child undergo laparoscopic surgery as recommended. | |||||

| In this situation, I would expect an overall good surgical outcome. | |||||

| In this situation, I would expect short-term negative consequences for my child (e.g., pain, longer than average surgery time). | |||||

| In this situation, I would feel safe to have my child operated on laparoscopically as recommended. | |||||

| In this situation, the recommended laparoscopic procedure would make sense for my child. | |||||

| In this situation, I would expect technical problems during the operation. | |||||

| In this situation, I would expect a complete solution to the problem. | |||||

| In this situation, I would like to have my child operated on laparoscopically as recommended. |

| Do Not Agree at All | Do Not Agree | Neither | Agree | Fully Agree | Don’t Know | |

| My family would advise me to have the surgery laparoscopically as recommended. | ||||||

| My friends would advise me to have the surgery laparoscopically as recommended. | ||||||

| Other physicians would advise me to have the surgery laparoscopically as recommended. |

- Scenario part 2

- Please put yourself in the position described as best you can and answer the following questions regarding your 1-year-old’s robotic-assisted surgery for ureteral stenosis.

| 0 Not at All | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 Very Strong | |

| I feel surprised. | |||||||||||

| I feel anxious. | |||||||||||

| I feel disgusted. | |||||||||||

| I feel angry. | |||||||||||

| I feel sad. | |||||||||||

| I feel happy. |

| Do Not Agree at All | Do Not Agree | Neither | Agree | Fully Agree | |

| In this situation, I would expect a complete solution to the problem. | |||||

| In this situation, I would be willing to let my child undergo robot-assisted surgery as recommended. | |||||

| In this situation, I would feel safe to let my child undergo robot-assisted surgery as recommended. | |||||

| In this situation, the recommended robotic-assisted surgery would be useful for my child. | |||||

| In this situation, I would expect long-term negative consequences for my child (e.g., irreversible damage, follow-up surgery). | |||||

| In this situation, I would like to have my child undergo robot-assisted surgery as recommended. | |||||

| In this situation, I would expect short-term negative consequences for my child (e.g., pain, longer than average surgery time). | |||||

| In this situation, I would expect technical problems during the operation. | |||||

| In this situation, I would expect an overall good surgical outcome. |

| Do Not Agree at All | Do Not Agree | Neither | Agree | Fully Agree | Don’t Know | |

| My friends would advise me to have the surgery robot-assisted as recommended. | ||||||

| My family would advise me to have the surgery robot-assisted as recommended. | ||||||

| Other physicians would advise me to have the surgery robot-assisted as recommended. |

- Questionnaire

| The following questions are about you. | ||||||

| Gender | male |  | female |  | diverse |  |

| Age __________ | ||||||

| Number of children ______________ | ||||||

| Highest school degree | ||||||

| No school-leaving qualification (yet) | |||||

| Secondary school diploma | |||||

| Secondary school leaving certificate | |||||

| Abitur (general university entrance qualification), subject-related university entrance qualification or technical college entrance qualification | |||||

| University degree (Bachelor, Master, Magister, Diploma, State Examination, Doctorate) | |||||

| Other: ________________________________________________ | |||||

| Have you ever had surgery? | Yes |  | No |  | ||

| If yes: Under general anaesthesia? | Yes |  | No |  | ||

| If yes: Robot-assisted? | Yes |  | No |  | ||

| Have any of your children ever had surgery? | Yes |  | No |  | ||

| If yes: Under general anaesthesia? | Yes |  | No |  | ||

| If yes: Robot-assisted? | Yes |  | No |  | ||

| Is a robot-assisted surgical procedure planned for any of your children in the near future? | ||||||

| Yes |  | No |  | Don’t know |  | |

| If you are or actually were in the situation described in the scenarios, what additional information would you have wanted in the decision-making process? | ||||||

| _____________________________________________________________________________________ | ||||||

| _____________________________________________________________________________________ | ||||||

| _____________________________________________________________________________________ | ||||||

| Thank you for your participation! | ||||||

References

- Meininger, D.; Byhahn, C.; Heller, K.; Gutt, C.; Westphal, K. Totally endoscopic Nissen fundoplication with a robotic system in a child. Surg. Endosc. 2001, 15, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarrete Arellano, M.; Garibay González, F. Robot-Assisted Laparoscopic and Thoracoscopic Surgery: Prospective Series of 186 Pediatric Surgeries. Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varda, B.K.; Wang, Y.; Chung, B.I.; Lee, R.S.; Kurtz, M.P.; Nelson, C.P.; Chang, S.L. Has the robot caught up? National trends in utilization, perioperative outcomes, and cost for open, laparoscopic, and robotic pediatric pyeloplasty in the United States from 2003 to 2015. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2018, 14, 336.e1–336.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denning, N.-L.; Kallis, M.P.; Prince, J.M. Pediatric Robotic Surgery. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 100, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kafka, I.Z.; Kocherov, S.; Jaber, J.; Chertin, B. Pediatric robotic-assisted laparoscopic pyeloplasty (RALP): Does weight matter? Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2019, 35, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinaro, F.; Angotti, R.; Bindi, E.; Pellegrino, C.; Fusi, G.; Luzzi, L.; Tosi, N.; Messina, M.; Mattioli, G. Low Weight Child: Can It Be Considered a Limit of Robotic Surgery? Experience of Two Centers. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. Part A 2019, 29, 698–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, N.; Farhat, W.A. A Comprehensive Analysis of Robot-Assisted Surgery Uptake in the Pediatric Surgical Discipline. Front. Surg. 2019, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cundy, T.P.; Harley, S.J.D.; Marcus, H.J.; Hughes-Hallett, A.; Khurana, S. Global trends in paediatric robot-assisted urological surgery: A bibliometric and Progressive Scholarly Acceptance analysis. J. Robot. Surg. 2017, 12, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C. Robotic Urologic Surgery in Infants: Results and Complications. Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangle, P.; Kearns, J.; Anderson, B.; Gundeti, M. Outcomes of Infants Undergoing Robot-Assisted Laparoscopic Pyeloplasty Compared to Open Repair. J. Urol. 2013, 190, 2221–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, V.; Bruyere, F.; Escoffre, J.M.; Binet, A.; Lardy, H.; Marret, H.; Marchal, F.; Hebert, T. Experience implication in subjective surgical ergonomics comparison between laparoscopic and robot-assisted surgeries. J. Robot. Surg. 2019, 14, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harel, M.; Herbst, K.; Silvis, R.; Makari, J.; Ferrer, F.; Kim, C. Objective pain assessment after ureteral reimplantation: Comparison of open versus robotic approach. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2015, 11, 82.e1–82.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.J.; Peters, C.A. Robotic Assisted Surgery in Pediatric Urology: Current Status and Future Directions. Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak, M.; Sinha, A.; Vig, A.; Saxena, R. Robotic surgery in paediatric patients: Our initial experience and roadmap for successful implementation of robotic surgery programme. J. Minimal Access Surg. 2021, 17, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boys, J.A.; Alicuben, E.T.; Demeester, M.J.; Worrell, S.G.; Oh, D.S.; Hagen, J.A.; Demeester, S.R. Public perceptions on robotic surgery, hospitals with robots, and surgeons that use them. Surg. Endosc. 2016, 30, 1310–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markar, S.R.; Kolic, I.; Karthikesalingam, A.P.; Wagner, O.; Hagen, M.E. International survey study of attitudes towards robotic surgery. J. Robot. Surg. 2012, 6, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irani, M.; Prabakar, C.; Nematian, S.; Julka, N.; Bhatt, D.; Bral, P. Patient Perceptions of Open, Laparoscopic, and Robotic Gynecological Surgeries. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McDermott, H.; Choudhury, N.; Lewin-Runacres, M.; Aemn, I.; Moss, E. Gender differences in understanding and acceptance of robot-assisted surgery. J. Robot. Surg. 2020, 14, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jank, B.J.; Haas, M.; Riss, D.; Baumgartner, W. Acceptance of patients towards task-autonomous robotic cochlear implantation: An exploratory study. Int. J. Med. Robot. Comput. Assist. Surg. 2021, 17, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anania, E.C.; Rice, S.; Winter, S.R. Building a predictive model of U.S. patient willingness to undergo robotic surgery. J. Robot. Surg. 2021, 15, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cundy, T.P.; Harling, L.; Hughes-Hallett, A.; Mayer, E.; Najmaldin, A.S.; Athanasiou, T.; Yang, G.-Z.; Darzi, A. Meta-analysis of robot-assisted vs. conventional laparoscopic and open pyeloplasty in children. Br. J. Urol. 2014, 114, 582–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkowska, W.; Gaul, S.; Ziefle, M. A Small but Significant Difference—The Role of Gender on Acceptance of Medical Assistive Technologies. In HCI in Work and Learning, Life and Leisure, Proceedings of the 6th Symposium of the Workgroup Human-Computer Interaction and Usability Engineering, USAB 2010, Klagenfurt, Austria, 4–5 November 2010; Leitner, G., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 82–100. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, P.; Friesen, W.V. Constants across cultures in the face and emotion. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1971, 17, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- R Core Team. R Version 4.0.5; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Ahmad, Z.F.; Carleton, J.D.; Agarwala, A. Robotic surgery: Current perceptions and the clinical evidence. Surg. Endosc. 2017, 31, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Andrés-Sánchez, J.; Almahameed, A.A.; Arias-Oliva, M.; Pelegrín-Borondo, J. Multinomial Logistic Regression and Configurational Analyses of the Factors Influencing Patients’ Acceptance of Surgical Robots. SSRN J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Liu, J. A Computational Approach to Characterizing the Impact of Social Influence on Individuals’ Vaccination Decision Making. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Larson, H.J.; Cooper, L.Z.; Eskola, J.; Katz, S.L.; Ratzan, S. Addressing the vaccine confidence gap. Lancet 2011, 378, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.T.; Yeung, N.C.; Choi, K.; Cheng, M.Y.; Tsui, H.; Griffiths, S. Factors in association with acceptability of A/H1N1 vaccination during the influenza A/H1N1 pandemic phase in the Hong Kong general population. Vaccine 2010, 28, 4632–4637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomicino, L.; Maccacari, E.; Buchini, S. Levels of anxiety in parents in the 24 hr before and after their child’s surgery: A descriptive study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, S.M. Quantitative measurement of anxiety in patients undergoing surgery for renal calculus disease. J. Adv. Nurs. 1990, 15, 962–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrarese, A.; Pozzi, G.; Borghi, F.; Pellegrino, L.; DI Lorenzo, P.; Amato, B.; Santangelo, M.; Niola, M.; Martino, V.; Capassso, E. Informed consent in robotic surgery: Quality of information and patient perception. Open Med. 2016, 11, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Clinic (n = 92) | Online (n = 95) | Total (n = 187) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | M = 38.5 (SD = 6.77) | M = 36.6 (SD = 8.61) | M = 37.5 (SD = 7.82) | |

| Number of children | M = 2.06 (SD = 0.98) | M = 1.87 (SD = 1.31) | M = 1.96 (SD = 1.16) | |

| Gender | Female | 72 (78.3%) | 45 (47.4%) | 117 (62.6%) |

| Male | 18 (19.6%) | 50 (52.6%) | 68 (36.4%) | |

| Divers | 1 (1.1%) | - | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Not given | 1 (1.1%) | - | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Highest graduation | No graduation (yet) | - | 1 (1.1%) | 1 (0.5%) |

| Secondary modern school qualification | 4 (4.3%) | - | 4 (2.1%) | |

| Higher school diploma | 31 (33.7%) | 3 (3.1%) | 34 (18.2%) | |

| High school diploma | 24 (26.1%) | 21 (22.1%) | 45 (24.1%) | |

| University degree | 29 (31.5%) | 70 (73.7%) | 99 (53%) | |

| Not given | 4 (4.4%) | - | 4 (2.1%) | |

| Previous surgery parent | Yes | 83 (90.2%) | 56 (59.9%) | 139 (74.4%) |

| No | 8 (8.7%) | 39 (41.1%) | 47 (25.1%) | |

| Not given | 1 (1.1%) | - | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Under general anesthesia | 76 (82.6%) | 48 (50.5) | 124 (66.3%) | |

| RA | 1 (1.3%) | 2 (2.1%) | 3 (1.6%) | |

| Previous surgery child | Yes | 55 (59.8%) | 16 (16.8%) | 71 (38%) |

| No | 36 (39.1%) | 79 (83.2%) | 115 (61.5%) | |

| Not given | 1 (1.1%) | - | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Under general anesthesia | 54 (58.7%) | 13 (13.7%) | 67 (35.8) | |

| RA | 14 (15.2%) | - | 14 (7.5%) | |

| RA surgery planned | Yes | 3 (3.3%) | 1 (1.1%) | 4 (2.1%) |

| No | 74 (80.4%) | 83 (87.4%) | 157 (84%) | |

| I don’t know | 14 (15.2%) | 11 (11.5%) | 25 (13.4%) | |

| Not given | 1 (1.1%) | - | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Attitude towards technology in general | Rating 1–5 | Mean = 3.91 (SD = 0.54) | Mean = 4.18 (SD = 0.65) | Mean = 4.05 (SD = 0.61) |

| Variable | Robot-Assisted Surgery | Laparoscopic Surgery | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional reaction: anxious | 6.33 (2.89) | 5.96 (2.96) | p = 0.03 |

| Perceived benefit | 3.93 (0.65) | 4.09 (0.64) | p = 0.006 * |

| Perceived risk | 2.52 (0.79) | 2.52 (0.70) | p = 0.99 |

| Assumed attitude of social environment | 2.95 (1.31) | 3.45 (1.16) | p < 0.001 * |

| Behavioral Intention | 3.63 (0.96) | 3.97 (0.74) | p < 0.001 * |

| Model 1 a | Model 2 | Model 3a | Model 3b | Model 3c | Model 3d | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted Variable | Behavioral Intention | Behavioral Intention | Anxiety | Perceived Benefits | Perceived Risks | Attitude of Social Environment | Behavioral Intention |

| Predictors | |||||||

| Familiarity | 0.17 (p = 0.001) * | 0.13 (p = 0.007) | −0.06 (p = 0.253) | 0.11 (p = 0.041) | −0.10 (p = 0.074) | 0.08 (p = 0.125) | 0.05 (p = 0.112) |

| Attitude technology | 0.23 (p < 0.001) * | 0.23 (p < 0.001) * | 0.03 (p = 0.541) | .23 (p < 0.001) * | −0.18 (p = 0.001) * | 0.25 (p < 0.001) * | 0.01 (p = 0.654) |

| Previous Operation Child | −0.24 (p = 0.025) | −0.23 (p = 0.024) | 0.49 (p < 0.001) * | −0.25 (p = 0.021) | 0.29 (p = 0.015) | −0.21 (p < 0.001) * | 0.02 (p = 0.762) |

| Operation method (RA vs. LA) | −0.34 (p < 0.001)* | 0.11 (p = 0.122) | −0.21 (p = 0.025) | −0.05 (p = 0.640) | −0.44 (p < 0.001) * | −0.07 (p = 0.281) | |

| Age of child (7 vs. 1 years) | 0.09 (p = 0.338) | −0.21 (p = 0.054) | 0.10 (p = 0.331) | −0.05 (p = 0.668) | −0.03 (p = 0.803) | 0.05 (p = 0.407) | |

| Anxiety | −0.13 (p < 0.001) * | ||||||

| Perceived benefits | 0.42 (p < 0.001) * | ||||||

| Perceived risks | −0.04 (p = 0.224) | ||||||

| Attitude of social environment | 0.43 (p < 0.001) * | ||||||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.73 |

| (Cox and Snell) | |||||||

| Significance Model | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ammer, E.; Mandt, L.S.; Silbersdorff, I.C.; Kahl, F.; Hagmayer, Y. Robotic Anxiety—Parents’ Perception of Robot-Assisted Pediatric Surgery. Children 2022, 9, 399. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9030399

Ammer E, Mandt LS, Silbersdorff IC, Kahl F, Hagmayer Y. Robotic Anxiety—Parents’ Perception of Robot-Assisted Pediatric Surgery. Children. 2022; 9(3):399. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9030399

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmmer, Elisabeth, Laura Sophie Mandt, Isabelle Christine Silbersdorff, Fritz Kahl, and York Hagmayer. 2022. "Robotic Anxiety—Parents’ Perception of Robot-Assisted Pediatric Surgery" Children 9, no. 3: 399. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9030399