The Influence of Family Multi-Institutional Involvement on Children’s Health Management Practices

Abstract

:1. Introduction

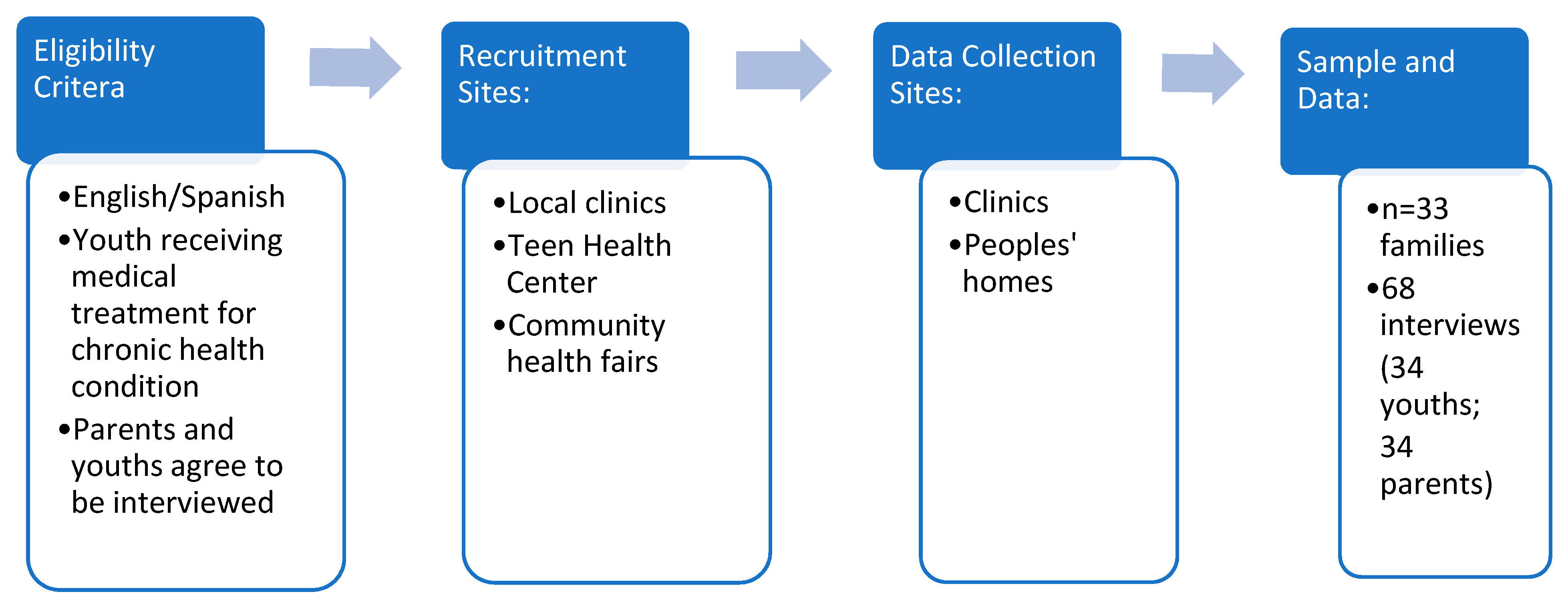

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Multiple Institutions Managing the Youths’ Illness

3.1.1. Diffused Services across Institutions

3.1.2. Limited Treatment Accessed via Multiple Institutions

- Elisa:

- I always get new teachers, uh not teachers, students. Like, students, they are only there for a little bit because they are in training. They are not an actual person that works there that’s gonna be my therapist for long term.

- Interviewer:

- Have you told them that you want a therapist that is going to be there for a long time?

- Elisa:

- (nods yes)

- Interviewer:

- And what have they told you?

- Elisa:

- (shakes head) …they would be giving you a student who lasts for a month, and then the next like a month or two and then the next month would be a different person so I can’t have a relationship. Like a relationship that I know I can trust that person. So, it’s hard to tell how I really feel if they keep on changing the person…

- Interviewer:

- How many different people have you spoken to?

- Elisa:

- More than ten … I’ve only had therapy for two years… they say the same thing, but then when I start on them, it just goes away.

- Interviewer:

- Oh, so once you start getting comfortable, they switch them on you. And you’ve spoken to somebody in charge about that?

- Elisa:

- (Shakes head yes)

- Interviewer:

- And they don’t tell you anything like we’ll see…

- Elisa:

- “We’ll see what we can do.” But that never happens.

- Norma:

- She’s a fighter… she don’t care… she’ll beat anybody that’s in her way… She don’t like you (fist hitting palm) that’s my little angel

- Interviewer:

- Does she go to therapy?

- Norma:

- She’s supposed to go to therapy, but she cursed them out so soon…there’s no way they’re gonna take her…

- Interviewer:

- So, when was the last time she went to the doctors

- Norma:

- One month ago, and then they closed the case, and they have to reopen it…In order to receive the medication from the psychiatrist she has to go to therapy

- Interviewer:

- Oh, I see… so you have to reopen the case

- Norma:

- I have to do everything… I have to fight …

- Interviewer:

- When she went to therapy how long was the session

- Norma:

- 45 min or less… she can have a bad day at school, and I go over there, and the therapist will say “what happened” or “your mother is with you, ok … it’s not bad.”

3.1.3. Conflicting Medical Advice across Institutions

- Bob:

- When I get sick, it hits me hard. So, I went to the doctor at my school … She told me something, and then when I went to my doctor [at the hospital], Flores—I love Flores—she was like, “What she said is not true.” [Laughs] … it was just like I felt the tension. … she [at school] was like, “Oh, do you have asthma?” I was like, “Yeah, I have asthma.” And she’s like, “Oh, you mighta had asthma attack.” I’m like, “I didn’t drop on the floor. I’m great. I’m alive.” She was like, “Oh, there’s different levels of asthma attacks. You can cough a lot; that’s an asthma attack. You can go on the ground; that’s the extreme.” … she’s [Dr. Flores] like, “That’s not an asthma attack. You did not have an asthma attack. Then my mom [said]… “Yes, you did have an asthma attack.”

- Author:

- So, when you were at school … what happened? Did she send you home? Or did she send you to the doctor, the hospital?...

- Bob:

- It was either a pill or some Motrin she gave me…. she gave me a pump, too. ‘Cause I never carry my pump. So, she’s like, “Here, a pump.” And then I had to take some pumps in front of her, ‘cause I forgot how to take pumps…

- Author:

- And that helped you, the pumps, or no?

- Bob:

- Not that I know of.

3.2. Multiple Involvement across Issues/Members

3.2.1. Leveraging Treatment via a Non-Health Institution

- Penny:

- They’re under Medicaid right now… I put in for court papers for child support for my seven-year-old, but they still haven’t done that yet. Once they go through with that process, she’ll probably be put on his [her father’s] insurance as well…He works for the police department, and he has HIP through the job …that’s what Ivy [her oldest child] has. Her basic insurance is HIP, and her secondary is Medicaid… If HIP doesn’t cover for something, her secondary insurance, which is Medicaid, covers. Like mostly for prescriptions—what do you call that?—referrals, Medicaid takes over for that.

3.2.2. Limited Family Resources Spread over Multiple Cases

- Dr. Peters:

- So, she needs a workup. She’s never had good control. Her sugars have always been high. When she was diagnosed, her A1C was like… 8.6. When we checked a year later, it was 8.8 And no one’s checked since. I just checked with them [Weingart hospital]. They haven’t seen her in the system for a year…. And the last time I had labs on you is May of last year… if it was me and my license, I wouldn’t just give you more meds. Your regimen right now isn’t working… We never had you in a good place… you still have to get to a good place.

- Gigi:

- Yeah

- Sulia:

- That’s why I said I run over there until they [Weingart] will see her… Because I know they, they, at school they do the, the-… you know? For her sugar.

- Dr. Peters:

- Yeah. Do you want to try to make her a pediatric endocrine appointment down at St. Simons?

- Sulia:

- We tried that… They say they don’t have all the stuff that she’s probably going to need.

- Dr. Peters:

- They sent you up to Weingart.

- Sulia:

- To Weingart.

- Dr. Peters:

- Okay. So, we are going to do two things. We’re going to call them first thing tomorrow to make an appointment. And what, what’s your number? Because I’m going to call them tomorrow first thing to make an appointment. I’m just going to make it… As soon as I can. Even if it’s a month out. I know it sucks. But I want her to go.

She tells me how much they all are frustrating/irritating her: Peter, Isabel, her husband. She says that on top of all that she has to deal with her brother, Martin. Martin is still in the home in Harlem and cannot speak because of a trachea tube. He is going to stay there, which is better for everyone because he would yell when he was irritated; she can still hear him screaming her name even though he is not in the house anymore. Isabel says she hopes Peter will take over Martin’s room and Lita says they cannot. Isabel explains to me that this is because Martin is an ACS [Administration for Children Services] case. I do not understand, and Isabel explains that Lita is his legal guardian. Lita also says the house is in his name, so they have to keep the room open for him for that reason as well.

Dr. Singh says they have a lot to talk about—her period, her food, and weight. The doctor asks Isabel want she wants to talk about first. Isabel just looks at her and says whatever… Lita starts talking about how she keeps reminding Isabel to take her pill, but she does not take it. She also talks about Peter not taking his pill—she had to remind him this morning before they left to make sure to take his pills. She does not let Isabel get a word in edgewise, nor does the doctor who does not interrupt her. She says she yells at her [to take the pills] … but nothing works. Isabel finally says at one point that Lita is a “liar.”

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Paik, L. Trapped in a Maze: How Social Control Institutions Drive Family Poverty and Inequality; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Kelly, P. The Hero’s Fight: African Americans in West Baltimore and the Shadow of the State; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush, D. Health Care Off the Books: Poverty, Illness, and Strategies for Survival in Urban America; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Anselm, S. Unending Work and Care: Managing Chronic Illness at Home; Jossey-Bass Inc. Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Radcliffe, E.; Karen, L.; Myfanwy, M. Co-construction of chronic illness narratives by older stroke survivors and their spouses. Sociol. Health Illn. 2013, 35, 993–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pals, R.A.S.; Imelda, C.; Timothy, S.; Dan, G. A delicate balance between control and flexibility: Experiences of care and support among pre-teenage children with type 1 diabetes and their families. Sociol. Health Illn. 2020, 43, 369–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prout, A.L.H.; Gelder, L. Medicines and the maintenance of ordinariness in the household management of childhood asthma. Sociol. Health Illn. 1999, 21, 137–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, S. Living with chronic illness in the family setting. Sociol. Health Illn. 2005, 27, 372–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.; Anselm, S. Managing Chronic Illness at Home: Three Lines of Work. Qual. Sociol. 1985, 8, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.; Anselm, S. Time for Dying; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Bury, M. Chronic Illness as biographical disruption. Sociol. Health Illn. 1982, 4, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B. It seems like you’re going around in circles’: Recurrent biographical disruption constructed through the past, present and anticipated future in the narratives of young adults with inflammatory bowel disease. Sociol. Health Illn. 2017, 39, 726–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaghan, L.; Gabe, J. Chronic illness as biographical contingency? Young people’s experiences of asthma. Sociol. Health Illn. 2015, 37, 1236–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meah, A.; Callery, P.; Milnes, L.; Rogers, S. Thinking ‘taller’: Sharing responsibility in the everyday lives of children with asthma. J. Clin. Nurs. 2009, 19, 1952–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaton, J.; Raisanen, U.; Salinas, M. Rule your condition, don’t let it rule you’: Young adults’ sense of mastery in their accounts of growing up with a chronic illness. Sociol. Health Illn. 2016, 38, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kingod, N.; Dan, G. In a vigilant state of chronic disruption: How parents with a young child with type 1 diabetes negotiate events and moments of uncertainty. Sociol. Health Illn. 2020, 42, 1473–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J. Parenting work and autism trajectories of care. Sociol. Health Illn. 2016, 38, 1106–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabe, J.; Bury, M.; Ramsay, R. Living with asthma: The experiences of young people at home and at school. Soc. Sci. Med. 2002, 55, 1619–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogensen, L.; Mason, J. The meaning of a label for teenagers negotiating identity: Experiences with autism spectrum disorder. Sociol. Health Illn. 2015, 37, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stjerna, M.L. Food, risk and place: Agency and negotiations of young people with food allergy. Sociol. Health Illn. 2015, 37, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gengler, A. Save My Kid: How Families of Critically Ill Children Cope, Hope, and Negotiate an Unequal Healthcare System; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, J. Cultural Health Capital: A Theoretical Approach to Understanding Health Care Interactions and the Dynamics of Unequal Treatment. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2010, 51, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gage-Bouchard, E. Culture, Styles of Institutional Interactions, and Inequalities in Healthcare Experiences. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2017, 58, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, L.K. Mama Might Be Better Off Dead: The Failure of Health Care in Urban America, 2nd ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dowrick, C. Why Do the O’Sheas Consult So Often? An Exploration of Complex Family Illness Behaviour. Soc. Sci. Med. 1992, 34, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2021 County Health Ranking Data. Available online: https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/explore-health-rankings/measures-data-sources/2021-measures (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Environmental and Health Data Portal. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Available online: https://a816-dohbesp.nyc.gov/IndicatorPublic/Subtopic.aspx?theme_code=2,3&subtopic_id=11 (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Kitzmann, K.; Dalton, W., III; Buscemi, J. Beyond Parenting Practices: Family Context and the Treatment of Pediatric Obesity. Fam. Relat. 2008, 57, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, L. Raising Generation RX: Mothering Kids with Invisible Disabilities in the Age of Inequality; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Link, B.; Phelan, J. Social Conditions as Fundamental Causes of Disease. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, 35, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Phelan, J.B.L.; Tehranifar, P. Social Conditions as Fundamental Causes of Health Inequalities: Theory, Evidence, and Policy Implications. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2010, 51, S28–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pearlin, L.I.; Schieman, S.; Fazio, E.M.; Meersman, S.C. Stress, health, and the life course: Some conceptual perspectives. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2005, 46, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, D.; Kristen, S. Advances in Families and Health Research in the 21st Century. J. Marriage Fam. 2010, 72, 743–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelman, J.; Mark, F. The Parental Stress Scale: Psychometric Properties in Families of Children with Chronic Health Conditions. Fam. Relat. 2018, 67, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardie, J.; Kristin, T. The Intergenerational Consequences of Parental Health Limitations. J. Marriage Fam. 2017, 79, 801–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umberson, D.; Mieke, B.T. Family Matters: Research on Family Ties and Health, 2010 to 2020. J. Marriage Fam. 2020, 82, 404–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burton, L.; Lea, B. Childhood Illness, Family Comorbidity, and Cumulative Disadvantage: An Ethnographic Treatise on Low-Income Mothers’ Health in Later Life. Annu. Rev. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2010, 30, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.S.; Linda, M.B. Between a Rock and a Hard Place: Socioeconomic (Im)mobility among Low-Income Mothers of Children with Disabilities. In Marginalized Mothers, Mothering from the Margins Advances in Gender Research; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018; Volume 25, pp. 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Arditti, J.; Linda, B.; Sara, N.-B. Maternal distress and parenting in the context of cumulative disadvantage. Fam. Process 2010, 49, 142–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, K. Getting Eyes in the Home: Child Protective Services Investigations and State Surveillance of Family Life. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2020, 85, 610–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Household (n = 33) | Parent (n = 34) | Youth (n = 34) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Structure | ||||

| Single parent | 45% | |||

| Two parent | 45% | |||

| Extended family | 9% | |||

| Work Status | ||||

| Not working | 39% | |||

| Part-time | 18% | |||

| Full-time | 39% | |||

| Unknown | 3% | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 6% | 41% | ||

| Female | 94% | 59% | ||

| Race | ||||

| Black | 26% | 24% | ||

| White | 6% | 0 | ||

| Latinx | 65% | 59% | ||

| Other (e.g., multiracial) | 3% | 18% | ||

| Age | ||||

| 12 | 15% | |||

| 13 | 9% | |||

| 14 | 18% | |||

| 15 | 26% | |||

| 16 | 21% | |||

| 17 | 9% | |||

| 18 | 3% | |||

| Median | 44 years | 15 years | ||

| Range | 24–60 years | 12–18 years |

| Illness | Total | Gender | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||

| Obesity | 10 (29%) | 4 (29%) | 6 (30%) |

| Asthma | 17 (50%) | 5 (36%) | 12 (60%) |

| Diabetes | 3 (9%) | 2 (14%) | 1 (5%) |

| Other | 4 (12%) | 3 (21%) | 1 (5%) |

| Total | 34 | 14 | 20 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paik, L. The Influence of Family Multi-Institutional Involvement on Children’s Health Management Practices. Children 2022, 9, 828. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9060828

Paik L. The Influence of Family Multi-Institutional Involvement on Children’s Health Management Practices. Children. 2022; 9(6):828. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9060828

Chicago/Turabian StylePaik, Leslie. 2022. "The Influence of Family Multi-Institutional Involvement on Children’s Health Management Practices" Children 9, no. 6: 828. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9060828

APA StylePaik, L. (2022). The Influence of Family Multi-Institutional Involvement on Children’s Health Management Practices. Children, 9(6), 828. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9060828