A Mixed Method Study: Defining the Core Learning Needs of Nurses Delivering Care to Children and Young People with Rheumatic Disease to Inform Paediatric Musculoskeletal Matters, a Free Online Educational Resource

Abstract

:1. Introduction

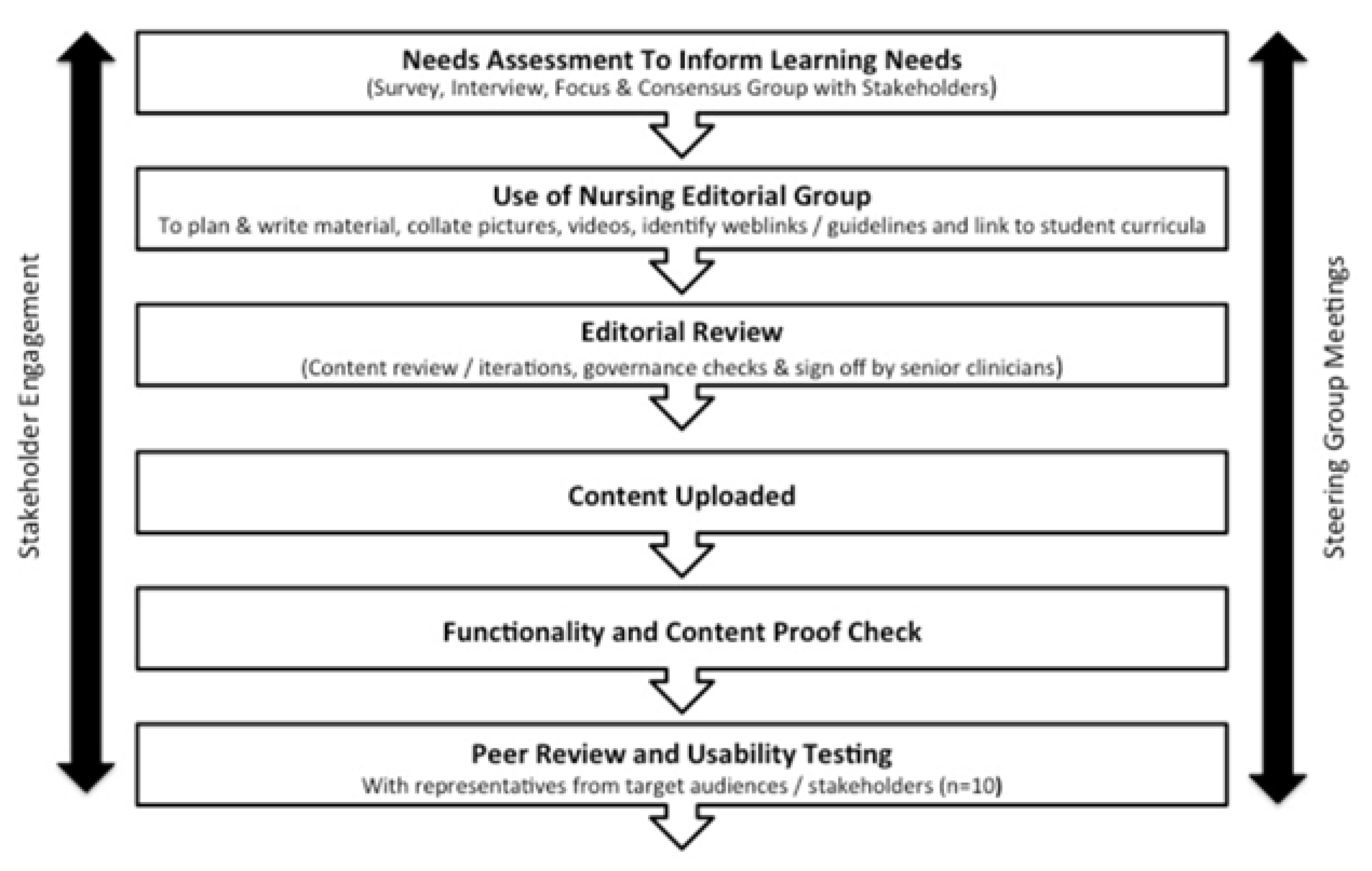

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Core MSK Learning Needs

- (1)

- Need for Increased Awareness about Rheumatic Disease

One of the most important aspects of care is that the nursing staff, looking after the child, in whatever setting, are able to recognise/identify if the child has a problem and know where to seek the appropriate assistance to deal with this.(CNS)

- (2)

- Impact of Experience and Nursing Role

I’d probably want some basic information about specific conditions that’s easy to understand because we’re often expected to explain to school staff as well, and then the impact that that condition has on a school day … For us it would be helpful to explain what the condition is and then how that then impacts on their day-to-day life.(School Nurse)

Rather than a generalist, we need to know everything about rheumatology. We actually need to know that pocket [of information] that relates to the study that we’re doing at that time....(Research Nurse)

I think like a sort of easy look database… so when somebody comes on you go ‘oh I’ve not looked after one of them before’ and then you can have a look and say ‘oh that’s what it is’.(General Paediatric Nurse)

Basically for us, as a team, I don’t know about the other teams, but we basically just go out and give the injections [to patients with JIA] and just a bit of support for the families really. So, knowing more around like you say, the side effects and the ongoing effects that might be pertinent to the children would be interesting so we can support them in the right direction.(Community Nurse)

My grandma has rheumatoid arthritis so I’ve kind of seen what it does to old people but I wouldn’t know how it would affect a child… It’ll be useful to have that comparison.(Student Nurse)

- (3)

- Need for Increased Knowledge about Rheumatic Disease and Management

Who they decide needs the steroids … the observations required so like a 2 h infusion and half hourly obs. and then an hour afterwards … how long [they] stay for ‘cos they are different to gastro patients.(General Paediatric Nurses)

That (impact) again isn’t us … That’s more, the physios come up and down to see the patients when they are here … and the specialist nurses would come.(General Paediatric Nurses)

I would be making sure I told their specialist nurse about what my concerns were. Because they are much better placed…to make sure they get the support and the right advice that they’re going to need to manage.(Research Nurses)

- (4)

- Design Components for an Impactful Learning and Information Resource

Be nice to have access to see what the school nurses would look at. Because obviously if a school nurse could ring us up and say ‘Tommy Jones is coming into school and he’s tired and he aching’ and all the rest of it. ‘Is that normal and what can he do and what can’t he do?’ So that would be nice’.(Community Nurse)

It makes it more real though, doesn’t it? If you can link into something. It stops being something that somebody somewhere might have and it becomes what real people have.(Student Nurses)

3.2. Peer Review and Initial User Feedback

Works for all levels of understanding, for students it gives them an introduction of what conditions to expect and for trained staff allows them to build on their knowledge and seek out anything further.(Ward sister)

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davies, K.; Cleary, G.; Foster, H.E.; Hutchinson, E.; Baildam, E. BSPAR Standards of Care for children and young people with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatology 2010, 49, 1406–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Weichao, Y.; Lewis, F.M.; Walker, A.J.; Ward, T.M. Struggling in the dark to help my child: Parents experience in caring for a young child with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J. Pediatric Nurs. 2017, 37, e23–e29. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A.; Craig, J.C.; Singh-Grewal, D. Children’s experiences of living with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: A thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Arthritis Care Res. 2012, 64, 1392–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patti, A.; Maggio, M.C.; Corsello, G.; Messina, G.; Iovane, A.; Palma, A. Evaluation of Fitness and the Balance Levels of Children with a Diagnosis of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kwon, H.J.; Kim, Y.L.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, S.M. A study on the physical fitness of children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2017, 29, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McDonagh, J.E.; Southwood, T.R. Unmet education and training needs of rheumatology health professionals in adolescent health and transitional care. Rheumatology 2004, 43, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nursing and Midwifery Council. The Code: Professional Standards of Practice and Behaviour for Nurses, Midwives and Nursing Associates; Nursing and Midwifery Council: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nursing Midwifery Council. Factsheet: Continuing Professional Development (CPD) for Nurses Working in the United Kingdom (UK); RCN: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Nursing. A Competency Framework for Rheumatology Nurses; RCN: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.rcn.org.uk/professional-development/publications/pub-009004 (accessed on 31 January 2022).

- Begum, J.; Nisar, M.K. Rheumatology Nurse Specialists and DMARD education: Is it fit for purpose? Rheumatology 2017, 56, kex062.138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spence, A.M.; Sinclair, L.; Morritt, M.L.; Laing, S. Knowledge and learning in specialty practice. J. Neonatal. Nurs. 2016, 22, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nursing Midwifery Council. Future Nurse: Standards of Proficiency for Registered Nurses. 2018. Available online: https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/education-standards/future-nurse-proficiencies.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- Gould, D.; Drey, N.; Berridge, E.J. Nurses’ experiences of continuing professional development. Nurse Educ. Today 2007, 27, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallion, J.; Brooke, J. Community and hospital-based nurses’ implementation of evidence-based practice: Are there any differences? Br. J. Community Nurs. 2016, 21, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boud, D.; Solomon, N. Work—Based Learning: A New Higher Education; The Society for Research into Higher Education; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Goff, I.; Boyd, D.; Wise, E.; Jandial, S.; Foster, H.E. Paediatric musculoskeletal learning needs for general practice trainees: Achieving an expert consensus. Educ. Prim. Care 2014, 25, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jandial, S.; Stewart, J.; Foster, H.E. What do they need to know: Achieving consensus on paediatric musculoskeletal content for medical students. BMC Med. Educ. 2015, 15, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Smith, N.; Rapley, T.; Jandial, S.; English, C.; Davies, B.; Wyllie, R.; Foster, H.E. Paediatric Musculoskeletal Matters (pmm)—Collaborative development of an online evidence based interactive learning tool and information resource for education in paediatric musculoskeletal medicine. Paediatr. Rheumatol. 2016, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Smith, N.; Foster, H.E.; Jandial, S. A mixed methods evaluation of the Paediatric Musculoskeletal Matters (PMM) online portfolio. Paediatr. Rheumatol. 2021, 19, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapley, T. Some pragmatics of qualitative data analysis. In Qualitative Research: Theory, Method & Practice; Silverman, D., Ed.; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2010; pp. 273–290. [Google Scholar]

- Popil, I. Promotion of critical thinking by using case studies as teaching method. Nurse Educ. Today 2011, 31, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benner, P. From Novice to Expert: Excellence and Power in Clinical Nursing Practice; Addison-Wesley: Menlo-Park, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Nursing. Career and Education Framework for Cancer Nursing: Guidance for Pre-Registration Nursing Students, Support Workers in Health and Social Care, Registered Nurses Providing General or Specialist Care; RCN: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- TREND-UK. An Integrated Career and Competency Framework for Diabetes Nursing, 4th ed.; SS Communications Group: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Nursing. Career, Education and Competence Framework for Neonatal Nursing in the UK; Neonatal RCN: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- NHS Health Education England. Safeguarding Children and Young People Programme. 2020. Available online: https://www.e-lfh.org.uk/programmes/safeguarding-children/ (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Foster, H.E.; Scott, C.; Tiderious, C.J.; Dobbs, M.B. Members of the Paediatric Global Musculoskeletal Task Force. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2020, 34, 101566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disease Knowledge | Management | Impact of Sisease/Condition | Available Support | Current and Topical Research | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paediatric rheumatology nurse specialist | Understanding of all rheumatological conditions affecting children and young people including the signs and symptoms of the conditions and disease processes, diagnosis process, classifications, how to manage these conditions and the investigations needed and why. Recognition of how these are different to adult conditions. Anatomy, physiology and pathophysiology– particularly that of joints and the musculoskeletal system. Blood test monitoring, regimes, results and what to do for abnormal results. | Common facts, tips and advice. Examination techniques including joint examinations/assessment and clinical examination skills including communication, key questioning, PGALS and diagnostic reasoning. Knowledge of how to take a clinical history. Knowledge of medications used to treat these conditions, why they are being used, when they can be given or not, when to withdraw treatment, how to administer safely, what the side effects are (and how to deal with them – including immunosuppressive nature of treatments) and monitoring. Safe handling of chemotherapy preparations and knowledge that Methotrexate is not a poisonous drug. Guidance on giving injectable therapies in particular to challenging patients and how to safely administer Subcutaneous and intravenous medication e.g., DMARD’s and biologics. Guidance on pain management and self-management of the condition. Prognosis of long-term conditions. What to expect in adult care/enabling adolescents to prepare for transition to adult service. Guidance on goals of treatment - Wallace criteria. Knowledge of roles and value of MDT within paediatric rheumatology and how to coordinate patient care. Assessment of disease activity, wellbeing and adjustment to illness. | An understanding of what it is like living with chronic disease/knowledge of the patients’ journey in relation to the most common rheumatological illnesses. Impact on the child and family and how to provide support. Effect on education and employment. | Up to date knowledge of safeguarding. Lifestyle and sexual health advice. How to tips e.g., letter writing to GP and other health professionals. Knowledge to educate patients, families and other professionals. Awareness of other support services and self help groups/charities to sign post families | National picture of paediatric rheumatology/National recommendations. Knowledge regarding ongoing research. Knowledge of national groups working to improve care and share information. |

| Adult rheumatology nurse | Basic understanding of rheumatological conditions affecting children and young people (in particular JIA and the subtypes of JIA), including the signs and symptoms of the conditions and disease processes, how to manage these conditions and the investigations needed and why, and how these are different to adult conditions. Highlight which conditions/subtypes of JIA are the main ones that affect patient’s health the most. The impact of age on the disease process. | Basic knowledge of the medications used to treat these conditions, why they are being used and why treatment is different for children and adults; including what age children can start biologics. Typical treatment plans for each condition. Detail on how children are typically managed highlighting areas where this differs to typical adult care. Differences between adult and child clinic set up. Detail on the transition process - increased understanding what paediatric team are doing before child comes to adult service and information to help them understand what the patient typically experiences in paediatrics. Immunisation advice. | Impact on child and family and where to refer patient/family to for information or support. The need to encourage normality and links to anything to support this. | Who to contact for advice/information/where they can go to obtain relevant information. What to do/where to go if they have safeguarding concerns. Information on career/employment/education support available and where to direct patients/families for this. Sexual health advice. Any relevant information that they can direct patients to. | What’s new in the area. New research. Recent guidelines. Topical articles. |

| Community nurse | Basic understanding of rheumatological conditions affecting children and young people including the signs and symptoms of the conditions and disease processes, and how to manage these conditions. | Basic knowledge of the medications used to treat these conditions, why they are being used, when they can be given (and not), how to administer safely and what the side effects are. Detail on the ongoing effects of treatment, dosage effects and effect of medication changes. What can be expected, how soon they will see/feel the effects etc. Guidance on how to recognise when have symptom control. Guidance on treatment follow up – e.g., how often do they need bloods etc. Home delivery details. | Impact on child and family and how to provide support. Provide full range of symptoms and guidance e.g., why red lump and what can be done? Why feel sick? What painkillers can the patient take? Advice for other professionals about what child can and cant do and what child should be like if treatment under control. | Who to contact for advice/information/where they can go to obtain relevant information. Support to direct parents/patients to. | New research. Links to useful articles. Highlight new treatments. |

| General paediatric nurse | Basic understanding of rheumatological conditions affecting children and young people including the signs and symptoms of the conditions and disease processes, and the investigations needed and why. | Basic knowledge of the medications used to treat these conditions, why they are being used, when they can be given (and not), when to withdraw treatment, how to administer safely and what the side effects are. How medications and treatment differs to that for other conditions e.g., differences in dosage. Basic blood monitoring requirements. Highlight where they differ to other conditions for example different blood tests, urine tests, observations etc. The process of treatment – whether need labs etc. Example of ‘normal’ patient experience – typical treatment plan. What to do in case of viral infections for patients on treatment and the need to recognise the immunosuppressive nature of treatments. Role of MDT and its importance and how rheumatology care is organized – when to speak to someone else and who to speak to. What to do if something goes wrong. | N/A for their role. | N/A for their role. | What’s new in the area. New research. Links to protocols/drug protocols. Highlight new treatments. |

| Health visitor | Basic understanding of rheumatological conditions affecting children and young people, including the signs and symptoms of the conditions (how likely to present) and what to look out for. Normal development (when are things normal and when aren’t they). | Basic knowledge of the medications used to treat these conditions. Good to know so they can signpost but not going to deal with directly. Guidance on what would ease symptoms. | Impact on child and family and what support they could/would offer in their role. | Support for parents – parent information sheets. | New research/current studies that may be relevant. Guidelines. |

| Research nurse | Basic understanding of rheumatological conditions affecting children and young people, including the signs and symptoms of the conditions and disease processes, and how to manage these conditions. Anatomy and physiology linked to the conditions and what’s affected. | Basic knowledge of the medications used to treat these conditions, why they are being used), what the side effects are and when to raise concern. Would be guided if using them so no in depth knowledge needed. Guidance on explaining things to children. | Impact on child and family. Quality of life. Coping with nausea. | N/A for their role. | NICE guidelines. |

| School nurse | Basic understanding of rheumatological conditions affecting children and young people, including the signs and symptoms of the conditions and how to manage them. | Basic knowledge of the medications used to treat these conditions (names so to recognise them), when they can be given (and not), how to administer safely and what the side effects are. Guidance on interaction with other things. The need to recognise the immunosuppressive nature of treatments and the impact of infectious disease. Role of MDT – who on team to contact and when. Emergency care and when to refer and to whom. Guidance on accidents e.g., what to do if they fall, will they have a bleed etc. Immunisation guidance. Typical care plans. | Impact on child and family, and guidance how they can provide support. Impact on school day and what support (if any) needs to be put in place at school. Information on expected school attendance and any impact that condition may have on this e.g., exceptions for late start. Advice on exercise and activities they should avoid (if any). | Who to contact for advice/information and a link to member of staff where possible. Chicken pox contact for patients on biologics, steroids and MTX and guidance on what they do. Support for school staff/information sheets. Guidance on where to signpost others too. Guidance on support/services for young people that they can signpost patients too. Safeguarding issues. | N/A for their role. |

| Student nurse | Basic understanding of rheumatological conditions affecting children and young people, including the signs and symptoms of the conditions and disease processes, and how to manage these conditions. Anatomy and physiology linked to the conditions and what’s affected. | Basic knowledge of the medications used to treat these conditions, why they are being used, when they can be given (and not), when to withdraw, how to administer safely and what the side effects are. Guidance on interaction with other things. Detail on how children are typically managed. Guidance on how to recognise when have symptom control. How treatment would differ depending if treatment is within a hospital or community setting. Information specifying differences that may exist in relation to management across countries or counties. What to do in case of viral infections for patients on treatment. The need to recognise the immunosuppressive nature of treatments and the impact of infectious diseases. Role of the MDT and its importance, and how rheumatology care is organized – who to speak to and when. | Impact on child and family and where to refer patient/family to for information or support. The need to encourage normality and links to anything to support this. Impact on school day and what support (if any) needs to be put in place at school. Information on expected school attendance and any impact that condition may have on this. Advice on exercise and activities (if any) they should avoid. Quality of life. | Support to direct patients/parents to. Guidance on support/services for young people they can signpost patients too. Parent information sheets. Support for school staff/information sheets. Guidance on where to signpost others to. Any relevant information that they can direct patients to. | What’s new in the area. Topical/useful articles. Highlight new treatments. |

| Subtheme 1: Pitch |

|

| Subtheme 2: Accessibility |

|

| Subtheme 3: Content presentation style |

|

| Subtheme 4: Format |

|

| Subtheme 5: Credibility |

|

| Subtheme 6: Governance of sensitive content |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Smith, N.; English, C.; Davies, B.; Wyllie, R.; Foster, H.E.; Rapley, T. A Mixed Method Study: Defining the Core Learning Needs of Nurses Delivering Care to Children and Young People with Rheumatic Disease to Inform Paediatric Musculoskeletal Matters, a Free Online Educational Resource. Children 2022, 9, 844. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9060844

Smith N, English C, Davies B, Wyllie R, Foster HE, Rapley T. A Mixed Method Study: Defining the Core Learning Needs of Nurses Delivering Care to Children and Young People with Rheumatic Disease to Inform Paediatric Musculoskeletal Matters, a Free Online Educational Resource. Children. 2022; 9(6):844. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9060844

Chicago/Turabian StyleSmith, Nicola, Christine English, Barbara Davies, Ruth Wyllie, Helen E. Foster, and Tim Rapley. 2022. "A Mixed Method Study: Defining the Core Learning Needs of Nurses Delivering Care to Children and Young People with Rheumatic Disease to Inform Paediatric Musculoskeletal Matters, a Free Online Educational Resource" Children 9, no. 6: 844. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9060844