Does Bullying Attitude Matter in School Bullying among Adolescent Students: Evidence from 34 OECD Countries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

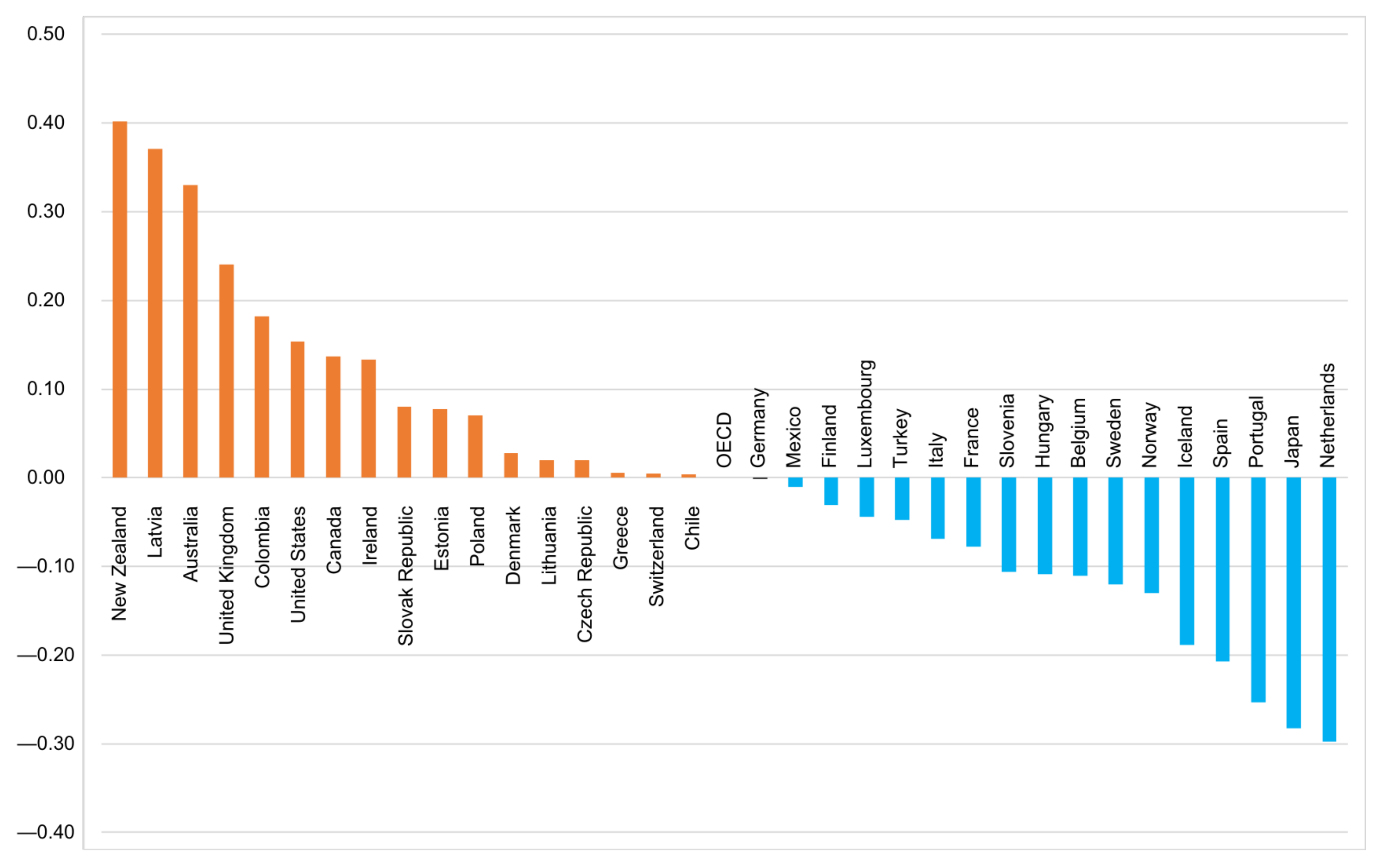

2.1. Data and Sample

2.2. Measurement

2.2.1. Independent Variables: Adolescent Bullying Attitudes

2.2.2. Outcome Variable: School Bullying Behavior

2.2.3. Mediators: Student Cooperation and Competition

2.2.4. Covariates

2.3. Analytic Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.2. Differences among Adolescent Bullying Attitudes, by Gender and Grade

3.3. The Effect of Adolescent Bullying Attitudes on School Bullying Behavior

3.4. Mediating Effects of Student Cooperation and Competition

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olweus, D.; Limber, S.P. Bullying in school: Evaluation and dissemination of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2010, 80, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klomek, A.B.; Sourander, A.; Elonheimo, H. Bullying by peers in childhood and effects on psychopathology, suicidality, and criminality in adulthood. Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 930–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladden, R.M.; Vivolo-Kantor, A.M.; Hamburger, M.E.; Lumpkin, C.D. Bullying Surveillance among Youths: Uniform Definitions for Public Health and Recommended Data Elements; Version 1.0.; National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and U.S. Department of Education: Atlanta, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Olweus, D. School bullying: Development and some important challenges. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 9, 751–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, K.; Smith, P.K. Is school bullying really on the rise? Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2011, 14, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, X.; Liu, J.; Xue, Z. Effects of bullying forms on adolescent mental health and protective factors: A global cross-regional research based on 65 countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. PISA 2018 Results: What School Life Means For Students’Lives. Available online: https://www.amazon.com.au/PISA-2018-results-Oecd/dp/9264970428 (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Yu, S.; Zhao, X. The negative impact of bullying victimization on academic literacy and social integration: Evidence from 51 countries in PISA. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2021, 4, 100151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaou, D. Identifying the effects of bullying victimization on schooling. Contemp. Econ. Policy 2021, 40, 162–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, H.J.; Chan, G.C.; Scott, J.G.; Connor, J.P.; Kelly, A.B.; Williams, J. Association of different forms of bullying victimisation with adolescents’ psychological distress and reduced emotional wellbeing. Aust. New Zealand J. Psychiatry 2016, 50, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, M.G.; Exum, M.L.; Brame, R.; Holt, T.J. Bullying victimization and adolescent mental health: General and typological effects across sex. J. Crim. Justice 2013, 41, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, C.F.; Huang, M.F.; Kim, Y.S.; Wang, P.W.; Tang, T.C.; Yeh, Y.C.; Lin, H.C.; Liu, T.L.; Wu, Y.Y.; Yang, P. Association between types of involvement in school bullying and different dimensions of anxiety symptoms and the moderating effects of age and gender in Taiwanese adolescents. Child Abus. Negl. 2013, 37, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, D.; Shipe, S.L.; Park, J.; Yoon, M. Bullying patterns and their associations with child maltreatment and adolescent psychosocial problems. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 129, 106–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.T.; Huang, X.C.; Huebner, E.S.; Tian, L.L. Association between bullying victimization and depressive symptoms in children: The mediating role of self-esteem. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 294, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staubli, S.; Killias, M. Long-term outcomes of passive bullying during childhood: Suicide attempts, victimization and offending. Eur. J. Criminol. 2011, 8, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.J.; Yu, Y.; Wilcox, H.C.; Kang, C.; Wang, K.; Wang, C.; Wu, Y.; Chen, R. Global risks of suicidal behaviours and being bullied and their association in adolescents: School-based health survey in 83 countries. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 19, 100–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shongwe, M.C.; Dlamini, L.P.; Simelane, M.S.; Masuku, S.K.S.; Shabalala, F.S. Are there Gender Differences in the Prevalence and Correlates of Bullying Victimization among in-School Youth in Eswatini? Sch. Ment. Health 2021, 13, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzypiec, G.; Alinsug, E.; Nasiruddin, U.A.; Andreou, E.; Brighi, A.; Didaskalou, E.; Guarini, A.; Kang, S.W.; Kaur, K.; Kwon, S.; et al. Self-reported harm of adolescent peer aggression in three world regions. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 85, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, C.R.; Williams, K.R.; Guerra, N.G.; Kim, T.E.; Sadek, S. Predictors of bullying and victimization in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic investigation. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2010, 25, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, L.; Chen, X.; Li, H. Bullying victimization, school belonging, academic engagement and achievement in adolescents in rural China: A serial mediation model. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 113, 104946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreou, E.; Vlachou, A.; Didaskalou, E. The Roles of Self-Efficacy, Peer Interactions and Attitudes in Bully-Victim Incidents. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2016, 26, 545–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldry, A.C. “What about bullying?” An experimental field study to understand students’ attitudes towards bullying and victimisation in Italian middle schools. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2004, 74, 583–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, C.E.; Lochman, J.E. Correcting for norm misperception of anti-bullying attitudes. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2019, 0165025419860598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslea, M.; Smith, P.K. Pupil and parent attitudes towards bullying in primary schools. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2000, 15, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espelage, D.L.; Hong, J.S.; Kim, D.H.; Nan, L. Empathy, Attitude Towards Bullying, Theory-of-Mind, and Non-physical Forms of Bully Perpetration and Victimization Among U.S. Middle School Students. Child Youth Care Forum 2017, 47, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, M.J.; Trueman, M.; Flemington, I. Associations between Secondary School Pupils’ Definitions of Bullying, Attitudes towards Bullying, and Tendencies to Engage in Bullying: Age and sex differences. Educ. Stud. 2010, 28, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmivalli, C.; Voeten, M. Connections between attitudes, group norms, and behaviour in bullying situations. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2016, 28, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, G.; Ruchkin, V.V.; Koposov, R.A.; Af Klinteberg, B. Pro-bullying attitudes among incarcerated juvenile delinquents: Antisocial behavior, psychopathic tendencies and violent crime. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2014, 37, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Camodeca, M.; Goossens, F.A. Children’s opinions on effective strategies to cope with bullying: The importance of bullying role and perspective. Educ. Res. 2007, 47, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.; Correia, I.; Marinho, S. Moral Disengagement, Normative Beliefs of Peer Group, and Attitudes Regarding Roles in Bullying. J. Sch. Violence 2010, 9, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azjen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Van Goethem, A.A.; Scholte, R.H.; Wiers, R.W. Explicit- and implicit bullying attitudes in relation to bullying behavior. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2010, 38, 829–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.; Johnson, D.W.; Johnson, R. Relationships among cooperative learning experiences, social interdependence, children’s aggression, victimization, and prosocial behaviors. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 41, 976–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, L.N.; Demaray, M.K.; Fredrick, S.S.; Summers, K.H. Associations among Middle School Students’ Bullying Roles and Social Skills. J. Sch. Violence 2014, 15, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stasio, M.R.; Savage, R.; Burgos, G. Social comparison, competition and teacher-student relationships in junior high school classrooms predicts bullying and victimization. J. Adolesc. 2016, 53, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morschheuser, B.; Hamari, J.; Maedche, A. Cooperation or competition—When do people contribute more? A field experiment on gamification of crowdsourcing. Int. J. Hum. -Comput. Stud. 2019, 127, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacus, S.M.; King, G.; Porro, G. Matching for Causal Inference without Balance Checking. Available SSRN 2008, 1152391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mitsopoulou, E.; Giovazolias, T. Personality traits, empathy and bullying behavior: A meta-analytic approach. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2015, 21, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, I.; Dalbert, C. School Bullying. Eur. Psychol. 2008, 13, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D. Familial and temperamental determinants of aggressive behavior in adolescent boys: A causal analysis. Dev. Psychol. 1980, 16, 644–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, K. Attitudes and beliefs about bullying among Australian school children. Ir. J. Psychol. 1997, 18, 202–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.K.; Brain, P. Bullying in schools: Lessons from two decades of research. Aggress. Behav. Off. J. Int. Soc. Res. Aggress. 2000, 26, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, M.; Mondry, M. “The game of bullying”: Shared beliefs and behavioral labels in bullying among middle schoolers. Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 2020, 24, 276–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, M.; Gumpel, T.P. The interplay between bystanders’ intervention styles: An examination of the “bullying circle” approach. J. Sch. Violence 2018, 17, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werth, J.M.; Nickerson, A.B.; Aloe, A.M.; Swearer, S.M. Bullying victimization and the social and emotional maladjustment of bystanders: A propensity score analysis. J. Sch. Psychol. 2015, 53, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, K.; Slee, P.T. Bullying among Australian school children: Reported behavior and attitudes toward victims. J. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 131, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenstra, R.; Lindenberg, S.; Huitsing, G.; Sainio, M.; Salmivalli, C. The role of teachers in bullying: The relation between antibullying attitudes, efficacy, and efforts to reduce bullying. J. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 106, 1135–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasman, L.R.; Albarracín, D. Forming attitudes that predict future behavior: A meta-analysis of the attitude-behavior relation. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 778–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Myers, D.G.; Sahajpal, P.; Behera, P. Social Psychology; McGraw Hill Education (India) Private Limited: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stankovic, S.; Santric-Milicevic, M.; Nikolic, D.; Bjelica, N.; Babic, U.; Rakic, L.; Terzic-Supic, Z.; Todorovic, J. The Association between Participation in Fights and Bullying and the Perception of School, Teachers, and Peers among School-Age Children in Serbia. Children 2022, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Before Matching (N = 206,362) | After Matching (N = 198,163) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Attitude towards bullying followers (AF) | 1.619 (0.819) | 1.608 (0.810) |

| Negative | 89.09% | 89.56% |

| Positive | 10.91% | 10.44% |

| Attitude towards bullying bystanders (AB) | 1.726 (0.786) | 1.716 (0.777) |

| Negative | 88.09% | 88.54% |

| Positive | 11.91% | 11.46% |

| Attitude towards bullying defenders (AD) | 3.112 (0.872) | 3.121 (0.866) |

| Negative | 17.04% | 16.59% |

| Positive | 82.96% | 83.41% |

| School bullying behavior | 0.009 (0.178) | 0.009 (0.178) |

| Student cooperation | 2.645 (0.666) | 2.653 (0.665) |

| Student competition | 2.524 (0.672) | 2.526 (0.671) |

| Gender | 0.495 (0.500) | 0.494 (0.500) |

| Female | 50.53% | 50.64% |

| Male | 49.47% | 49.36% |

| Grade | 0.674 (0.469) | 0.675 (0.468) |

| Middle school | 33.22% | 32.51% |

| High school | 66.78% | 67.49% |

| Absenteeism | 0.232 (0.424) | 0.218 (0.413) |

| No | 76.90% | 78.24% |

| Yes | 23.10% | 21.76% |

| Family’s economic status | 2.729 (0.479) | 2.740 (0.461) |

| Parental education | 1.695 (0.836) | 1.658 (0.796) |

| Parental involvement | 3.311 (0.684) | 3.339 (0.658) |

| Multivariate L1 | 0.261 | 0.123 |

| Treatment Group 95% CI | Control Group 95% CI | t-Test/Chi-Square Test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude towards bullying followers (AF) | 1.606 (1.601, 1.610) | 1.610 (1.604, 1.615) | 1.097 |

| Attitude towards bullying bystanders (AB) | 1.706 (1.701, 1.710) | 1.727 (1.722, 1.732) | 6.083 *** |

| Attitude towards bullying defenders (AD) | 3.144 (3.139, 3.150) | 3.096 (3.091, 3.102) | −12.377 *** |

| Student cooperation | 2.586 (2.582, 2.590) | 2.724 (2.720, 2.728) | 46.567 *** |

| Student competition | 2.599 (2.595, 2.603) | 2.449 (2.445, 2.454) | −49.873 *** |

| Gender | 0.515 (0.512, 0.518) | 0.471 (0.468, 0.475) | −19.210 *** |

| Grade | 0.657 (0.654, 0.660) | 0.693 (0.691, 0.696) | 17.175 *** |

| Absenteeism | 0.245 (0.242, 0.248) | 0.190 (0.187, 0.192) | −29.831 *** |

| Family’s economic status | 2.749 (2.746, 2.752) | 2.731 (2.728, 2.733) | −8.752 *** |

| Parental education | 1.643 (1.638, 1.648) | 1.673 (1.668, 1.680) | 8.296 *** |

| Parental involvement | 3.263 (3.259, 3.267) | 3.418 (3.414, 3.422) | 52.880 *** |

| Gender | Grade | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent Bullying Attitudes | Female | Male | Middle School | High School |

| Attitude towards bullying followers (AF) | 1.477 | 1.741 | 1.703 | 1.561 |

| t test | −73.477 *** | 36.654 *** | ||

| Attitude towards bullying bystanders (AB) | 1.544 | 1.893 | 1.823 | 1.664 |

| t test | −1.0 *** | 42.686 *** | ||

| Attitude towards bullying defenders (AD) | 3.298 | 2.939 | 3.030 | 3.164 |

| t test | 94.377 *** | −32.338 *** | ||

| Bullied Group 95% CI | Non-Bullied Group 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Attitude towards bullying followers (AF) | 0.012 *** (0.010, 0.014) | 0.011 *** (0.009, 0.013) |

| Attitude towards bullying bystanders (AB) | 0.002 (−0.000, 0.004) | 0.005 *** (0.003, 0.007) |

| Attitude towards bullying defenders (AD) | 0.004 *** (0.002, 0.005) | 0.006 *** (0.004, 0.007) |

| Student cooperation | −0.006 *** (−0.008, −0.004) | −0.007 *** (−0.009, −0.006) |

| Student competition | 0.031 *** (0.029, 0.033) | 0.031 *** (0.029, 0.032) |

| Gender | −0.006 ** (−0.009, −0.004) | −0.012 *** (−0.014, −0.010) |

| Grade | 0.0099 *** (0.006, 0.011) | −0.016 *** (−0.019, −0.014) |

| Absenteeism | 0.027 *** (0.025, 0.030) | 0.025 *** (0.022, 0.027) |

| Family’s economic status | 0.027 *** (0.024, 0.029) | 0.018 *** (0.015, 0.020) |

| Parental education | −0.016 *** (−0.018, −0.015) | −0.022 *** (−0.024, −0.021) |

| Parental involvement | 0.006 *** (0.004, 0.007) | −0.003 ** (−0.004, −0.001) |

| Constant | −0.137 *** (−0.150, −0.124) | −0.108 *** (−0.121, −0.095) |

| R2 | 0.033 | 0.038 |

| F | 314.49 | 343.54 |

| Observation | 101,600 | 96,563 |

| Outcome Variable | Mediator 1 | Mediator 2 | Outcome Variable | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| School Bullying Behavior | Student Cooperation | Student Competition | School Bullying Behavior | |

| Attitude towards bullying followers (AF) | 0.013 *** | −0.039 *** | 0.022 *** | 0.012 *** |

| Attitude towards bullying bystanders (AB) | 0.001 * | −0.091 *** | −0.039 *** | 0.002 ** |

| Attitude towards bullying defenders (AD) | 0.007 *** | 0.037 *** | 0.048 *** | 0.006 *** |

| Student cooperation | 0.113 *** | −0.011 *** | ||

| Student competition | 0.035 *** | |||

| R2 | 0.022 | 0.082 | 0.048 | 0.039 |

| F | 493.46 | 1965.07 | 994.61 | 736.33 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Man, X.; Liu, J.; Xue, Z. Does Bullying Attitude Matter in School Bullying among Adolescent Students: Evidence from 34 OECD Countries. Children 2022, 9, 975. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9070975

Man X, Liu J, Xue Z. Does Bullying Attitude Matter in School Bullying among Adolescent Students: Evidence from 34 OECD Countries. Children. 2022; 9(7):975. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9070975

Chicago/Turabian StyleMan, Xiaoou, Jiatong Liu, and Zengxin Xue. 2022. "Does Bullying Attitude Matter in School Bullying among Adolescent Students: Evidence from 34 OECD Countries" Children 9, no. 7: 975. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9070975

APA StyleMan, X., Liu, J., & Xue, Z. (2022). Does Bullying Attitude Matter in School Bullying among Adolescent Students: Evidence from 34 OECD Countries. Children, 9(7), 975. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9070975