Screen Time and Attention Subdomains in Children Aged 6 to 10 Years

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

Participants

3. Materials

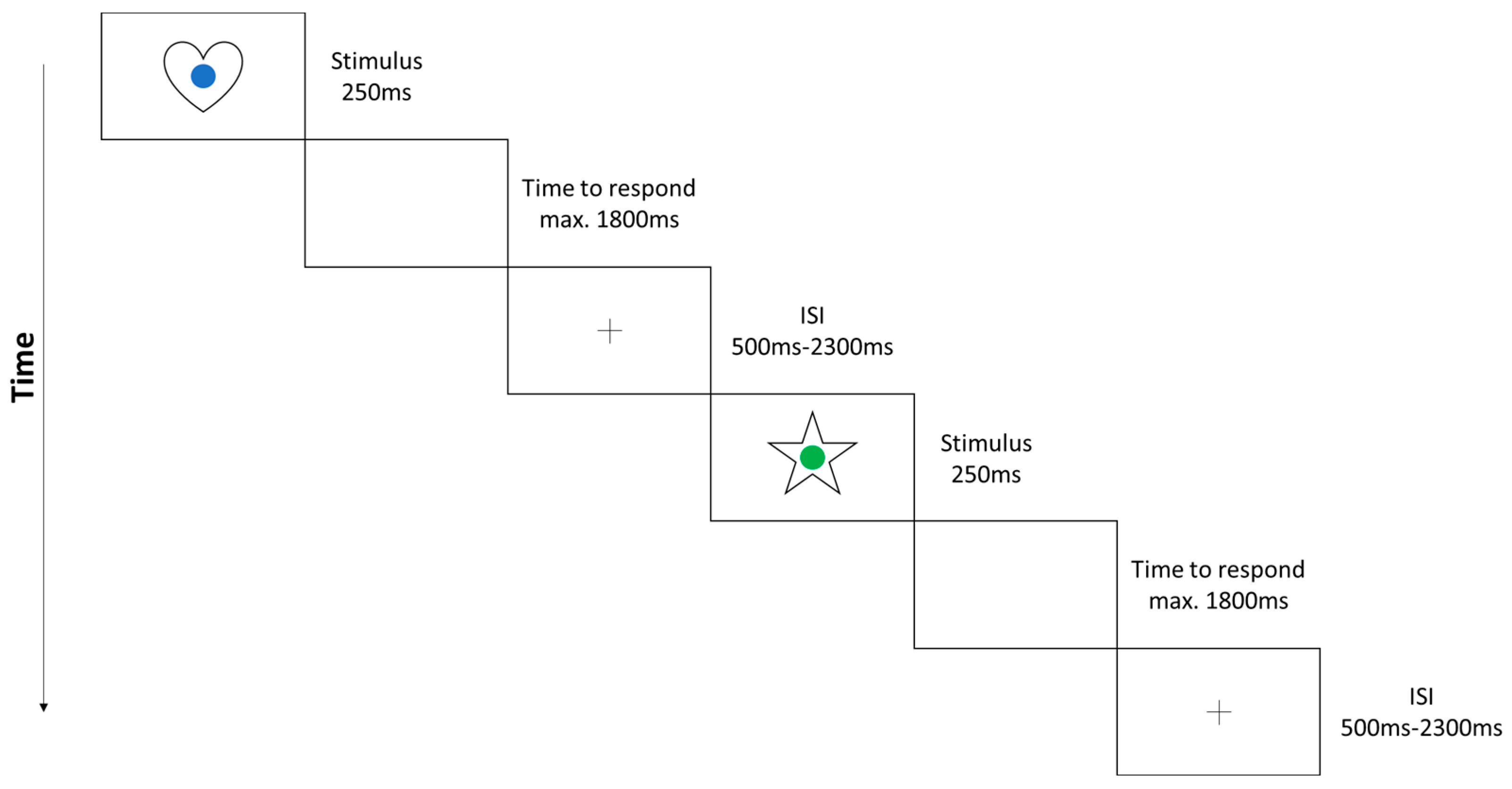

3.1. Attention Subdomains

3.2. Digital Media Use and Leisure Activity

4. Procedure

5. Statistical Analysis

6. Results

6.1. Descriptive Statistics

6.2. Associations between Media Use and Attentional Subdomains

7. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McNeill, J.; Howard, S.J.; Vella, S.A.; Cliff, D.P. Longitudinal Associations of Electronic Application Use and Media Program Viewing with Cognitive and Psychosocial Development in Preschoolers. Acad. Pediatr. 2019, 19, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radesky, J.S.; Schumacher, J.; Zuckerman, B. Mobile and Interactive Media Use by Young Children: The Good, the Bad, and the Unknown. Pediatrics 2015, 135, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twenge, J.M.; Campbell, W.K. Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and ad-olescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 12, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer-Grote, L.; Kothgassner, O.D.; Felnhofer, A. Risk factors for problematic smartphone use in children and adolescents: A review of existing literature. Neuropsychiatrie 2019, 33, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissak, G. Adverse physiological and psychological effects of screen time on children and adolescents: Literature review and case study. Environ. Res. 2018, 164, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkley, T.; Brown, H.; Carson, V.; Teychenne, M. Cross sectional associations of screen time and outdoor play with social skills in preschool children. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauce, B.; Liebherr, M.; Judd, N.; Klingberg, T. The impact of digital media on children’s intelligence while controlling for genetic differences in cognition and socioeconomic background. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid Chassiakos, Y.L.; Radesky, J.; Christakis, D.; Moreno, M.A.; Cross, C.; Council on Communications and Media; Hill, D.; Ameenuddin, N.; Hutchinson, J.; Levine, A.; et al. Children and Adolescents and Digital Media. Am. Acad. Pediatr. 2016, 138, e20162593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.J.; Barnes, J.D.; Tremblay, M.S.; Chaput, J.-P. Associations between duration and type of electronic screen use and cognition in US children. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 108, 106312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostyrka-Allchorne, K.; Cooper, N.R.; Simpson, A. The relationship between television exposure and children’s cognition and behaviour: A systematic review. Dev. Rev. 2017, 44, 19–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, M.P.; Squeglia, L.M.; Bagot, K.; Jacobus, J.; Kuplicki, R.; Breslin, F.J.; Bodurka, J.; Morris, A.S.; Thompson, W.K.; Bartsch, H.; et al. Screen media activity and brain structure in youth: Evidence for diverse structural correlation networks from the ABCD study. NeuroImage 2018, 185, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lingineni, R.K.; Biswas, S.; Ahmad, N.; E Jackson, B.; Bae, S.; Singh, K.P. Factors associated with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder among US children: Results from a national survey. BMC Pediatr. 2012, 12, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozmert, E.; Toyran, M.; Yurdakok, K. Behavioral correlates of television viewing in primary school children evaluated by the child behavior checklist. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2002, 156, 910–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Egmond-Fröhlich, A.W.A.; Weghuber, D.; De Zwaan, M. Association of Symptoms of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder with Physical Activity, Media Time, and Food Intake in Children and Adolescents. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e49781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, C.J. The influence of television and video game use on attention and school problems: A multivariate analysis with other risk factors controlled. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2010, 45, 808–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, E.M.; Watkins, S. The Value of Reanalysis: TV Viewing and Attention Problems. Child Dev. 2010, 81, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkes, A.; Sweeting, H.; Wight, D.; Henderson, M. Do television and electronic games predict children’s psychosocial adjustment? Longitudinal research using the UK Millennium Cohort Study. Arch. Dis. Child. 2013, 98, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmiedeler, S.; Niklas, F.; Schneider, W. Symptoms of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and home learning environment (HLE): Findings from a longitudinal study. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2014, 29, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.G.; Cohen, P.; Kasen, S.; Brook, J.S. Extensive Television Viewing and the Development of Attention and Learning Difficulties During Adolescence. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2007, 161, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, C.S.; Bavelier, D. Learning, attentional control, and action video games. Curr. Biol. 2012, 22, R197–R206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dye, M.W.G.; Green, C.S.; Bavelier, D. The development of attention skills in action video game players. Neuropsychologia 2009, 47, 1780–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dye, M.W.; Bavelier, D. Differential development of visual attention skills in school-age children. Vis. Res. 2010, 50, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trisolini, C.D.; Petilli, M.A.; Daini, R. Is action video gaming related to sustained attention of adolescents? Quart. J. Exp. Psychol. 2018, 71, 1033–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzwagi, A.B.; Motiwala, F.B.; Manikkara, G.; Rizvi, A.; Varela, M.A.; Rush, A.J.; Zafar, M.K.; Jain, S.B. How Are Attention-deficit Hyperactivity and Internet Gaming Disorders Related in Children and Youth? J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2021, 27, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, H.; Coskun, M.; Ayaydin, H.; Adak, I.; Zoroglu, S.S. Prevalence and patterns of psychiatric disorders in referred adolescents with Internet addiction. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2013, 67, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkelen, S.W.; Vossen, H.G.; Valkenburg, P.M. Children’s Television Viewing and ADHD-related Behaviors: Evidence from the Netherlands. J. Child. Media 2015, 9, 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, F.J.; Christakis, D.A. Associations Between Content Types of Early Media Exposure and Subsequent Attentional Problems. Pediatrics 2007, 120, 986–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenzer, F. Beliebteste Funktionen von Smartphones/Handys unter Teenagern 2019. Statista 2022. Available online: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/181410/umfrage/beliebteste-mobiltelefon-funktionen-bei-kindern-und-jugendlichen/ (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Alobaid, L.; BinJadeed, H.; Alkhamis, A.; Alotaibi, R.; Tharkar, S.; Gosadi, I.; Gad, A. Burgeoning Rise In Smartphone Usage among School Children In Saudi Arabia: Baseline Assessment of Recognition and Attention Skills Among Users and Non-Users Using CANTAB Tests. Ulutas Med. J. 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebherr, M.; Schubert, P.; Antons, S.; Montag, C.; Brand, M. Smartphones and attention, curse or blessing?—A review on the effects of smartphone usage on attention, inhibition, and working memory. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2020, 1, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowd, J.M.; Shaw, R.J. Attention and aging: A functional perspective. In The Handbook of Aging and Cognition; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Liebherr, M.; Antons, S.; Brand, M. The SwAD-Task—An innovative paradigm for measuring costs of switching between dif-ferent attentional demands. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razel, M. The Complex Model of Television Viewing and Educational Achievement. J. Educ. Res. 2001, 94, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisch, S.M.; Truglio, R.T. Why children learn from Sesame Street. In G Is for Growing; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 255–266. [Google Scholar]

- Przybylski, A.K. Electronic Gaming and Psychosocial Adjustment. Pediatrics 2014, 134, e716–e722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, A.K.; Mishkin, A.F. How the quantity and quality of electronic gaming relates to adolescents’ academic engagement and psychosocial adjustment. Psychol. Popul. Media 2016, 5, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Joiner, T.E.; Rogers, M.L.; Martin, G.N. Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among US adolescents after 2010 and links to increased new media screen time. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 6, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Martin, G.N.; Campbell, W.K. Decreases in psychological well-being among American adolescents after 2012 and links to screen time during the rise of smartphone technology. Emotion 2018, 18, 765–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radesky, J.S.; Weeks, H.M.; Ball, R.; Schaller, A.; Yeo, S.; Durnez, J.; Tamayo-Rios, M.; Epstein, M.; Kirkorian, H.; Coyne, S.; et al. Young Children’s Use of Smartphones and Tablets. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20193518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Min | Max | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TV | 1 | 4 | 1.47 | 0.74 |

| Smartphone | 0 | 4 | 0.73 | 0.88 |

| Tablet | 0 | 3 | 0.70 | 0.83 |

| Game console | 0 | 5 | 1.04 | 1.14 |

| Computer | 0 | 3 | 0.29 | 0.58 |

| Overall media use | 1 | 12 | 4.22 | 2.41 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | Overall media use | - | ||||

| (2) | Single demand: selective | 0.120 | - | |||

| (3) | Single demand: divided | 0.017 | 0.593 ** | - | ||

| (4) | Switching demands: selective | 0.131 | 0.740 ** | 0.761 ** | - | |

| (5) | Switching demands: divided | 0.068 | 0.603 ** | 0.685 ** | 0.713 ** | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liebherr, M.; Kohler, M.; Brailovskaia, J.; Brand, M.; Antons, S. Screen Time and Attention Subdomains in Children Aged 6 to 10 Years. Children 2022, 9, 1393. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9091393

Liebherr M, Kohler M, Brailovskaia J, Brand M, Antons S. Screen Time and Attention Subdomains in Children Aged 6 to 10 Years. Children. 2022; 9(9):1393. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9091393

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiebherr, Magnus, Mark Kohler, Julia Brailovskaia, Matthias Brand, and Stephanie Antons. 2022. "Screen Time and Attention Subdomains in Children Aged 6 to 10 Years" Children 9, no. 9: 1393. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9091393

APA StyleLiebherr, M., Kohler, M., Brailovskaia, J., Brand, M., & Antons, S. (2022). Screen Time and Attention Subdomains in Children Aged 6 to 10 Years. Children, 9(9), 1393. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9091393