Disruptive Behavior Programs on Primary School Students: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Limits

2.2. Selection Criteria

- i.

- “Conducta antisocial” (Anti-Social behavior), “Inadaptación” (Inadaptation), “Trastornos de la personalidad” (Personality disorders), “Adaptación social” (Adaptación social), “Alienación social” (Social alienation), “Delincuencia juvenil” (Juvenile delinquency), “Comportamiento antisocial” (“Anti-social behavior“), “Conducta antisocial” (Anti-social conduct), “Inadaptación social” (Social Inadaptation)

- ii.

- “Disrupción” (Disruption): No results were found.

- iii.

- “Programa” (Program): Several types were found and “Programa de Educación” (Educational Program) was selected.

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Data Analysis

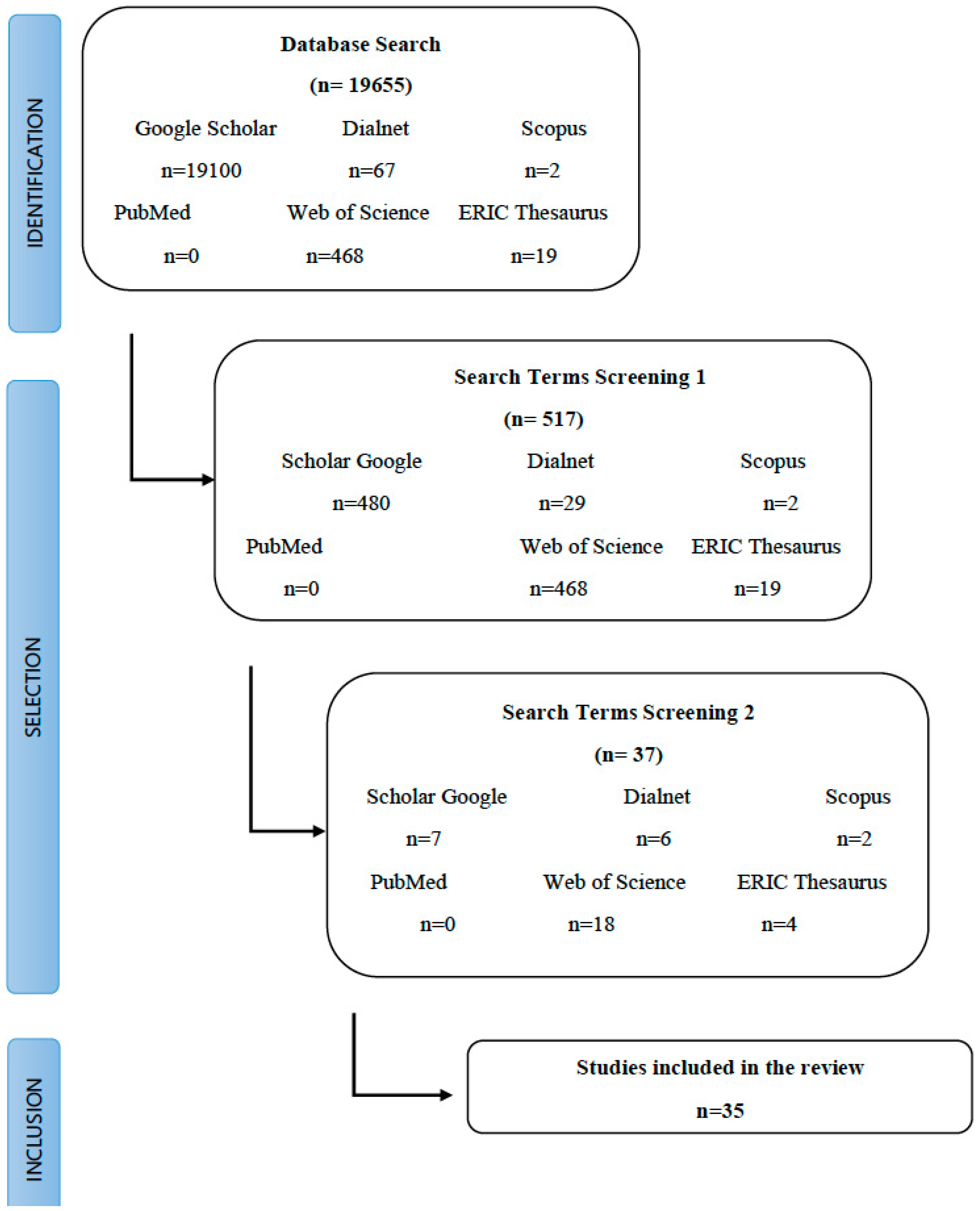

- i.

- Identification: Selection of databases (Google Scholar, Dialnet, Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science and ERIC Thesaurus) and general terminology (“conducta disruptiva” and “disruptive behavior”).

- ii.

- Screening 1: Selection of terminology in Spanish (see Table 1) and specific search in databases with Spanish documents (Google Scholar and Dialnet).

- iii.

- Screening 2: Selection of terminology in English (see Table 1) and specific search in the databases with documents in English (Google Scholar, Scopus, Pubmed, Web of Science and ERIC Thesaurus).

- iv.

- Inclusion: Reading and complete analysis of the documents and final selection where the fundamental requirement was to contain an intervention program.

3. Results

3.1. Study Locations and Evolution Over Time

3.2. Educational Stage of the Participants

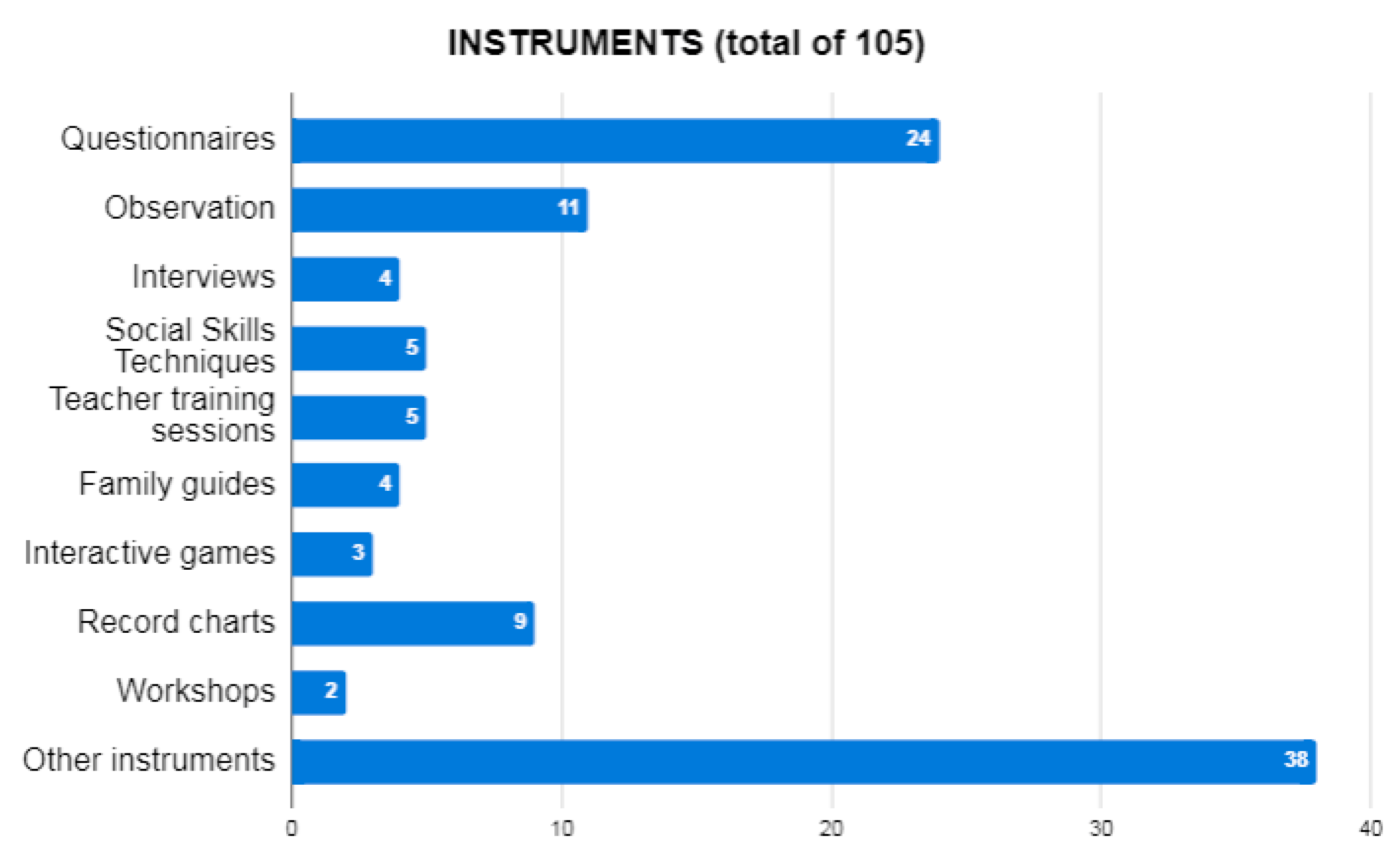

3.3. Instruments

3.4. Outcome Measures

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prados, M.A.H.; Morales, E.C. Formación Inicial de Los Maestros de Educación Infantil y las Conductas Disruptivas de la Convivencia Escolar. IV Congreso Internacional Virtual Sobre La Educación en el Siglo XXI. 2019. Available online: https://www.eumed.net/actas/19/educacion/1-formacion-inicial-de-los-maestros.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Alonso, J.D.; Castedo, A.L.; Juste, M.P.; Roales, E.A. School violence: The interpersonal teacher-student dyad. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2013, 3, 75–86. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- González, A.D.; Fernández, T.G.; García, D.A. What measures for the improvement of coexistence are being developed in educational centers: An insider’s perspective. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2013, 3, 207–213. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Jesús Comellas i Carbó, M.J.C. The daily climate in the classroom. Relational context of socialization. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2013, 3, 289–300. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, R.M.R. Clima Escolar y Procesos de Convivencia en el Desempeño Académico Estudiantil. Ph.D. Thesis, University of La Costa, Barranquilla, Colombia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gelabert, J. Restorative practices in Physical Education sessions: A tool for the reduction of disruptive behaviors. Didacticae 2019, 7, 86–102. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa, R.; Katsura, T. Role of Parenting Style in Children’s Behavioral Problems through the Transition from Preschool to Elementary School According to Gender in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pino, M.J.; Herruzo, J.; Herruzo, C. A New Intervention Procedure for Improving Classroom Behavior of Neglected Children: Say Do Say Correspondence Training. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Góngora, J.R.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Linares, J.J.G. Relationship between parental educational style and the level of adaptation of minors at social risk. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2013, 3, 301–318. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Ros, I. The student engagement with the school. Rev. Psicodidact. 2009, 14, 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ros, I.; Goikoetxea, J.; Gairín, J.; Lekue, P. Student Engagement in the School: Interpersonal and Inter-Center Differences. Rev. Psicodidact. 2012, 17, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodríguez-Fernández, A.; Ramos-Díaz, E.; Ros, I.; Zuazagoitia, A. School engagement of high school students: The influence of resilience, self-concept and perceived social support. Educación XX1 2018, 21, 87–108. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Halabi, F.; Ghandour, L.; Dib, R.; Zeinoun, P.; Maalouf, F.T. Correlates of bullying and its relationship with psychiatric disorders in Lebanese adolescents. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 261, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez, I.; Jorquera, A.B.; Ruiz-Esteban, C.; Martínez-Ramón, J.P.; Fernández-Sogorb, A. Emotional Intelligence, Bullying, and Cyberbullying in Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martino, E.A.; Hernández, M.Á.; Pañeda, P.C.; Mon, M.A.C.; de Mesa, C.G.G. Teachers’ perception of disruptive behaviour in the classrooms. Psicothema 2016, 28, 174–180. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, A.R. La Mediación para Resolver los Conflictos en las Aulas. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of the Basque Country, Leioa, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, M.V.M. Estudio y Análisis de Estrategias para la Resolución de Conductas Disruptivas en el Aula. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Granada, Granada, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Martín, R.B. Contextos de Aprendizaje: Formales, no Formales e Informales. Available online: http://148.202.167.116:8080/xmlui/handle/123456789/1004 (accessed on 13 September 2020).

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ohara, R.; Kanejima, Y.; Kitamura, M.; Izawa, K.P. Association between Social Skills and Motor Skills in Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2020, 10, 276–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Comission. KiVa Anti-Bullying Program; KiVa Program & University of Turku: Turku, Finland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, R. The Finnish KiVa Anti-Bullying Program. El Programa Anti-Acoso Escolar Finlandés KiVa; Instituto Escalae: Barcelona, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pichardo, M.C.; García, T.; Justicia, F.; Llanos, C. Effects of an intervention program for the improvement of social competence in elementary school children in Bolivia. Int. J. Psychol. Psychol. Ther. 2008, 8, 441–452. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Hijón, A.C. Evaluation of a behavioral management education program. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 7, 805–828. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Sliminng, E.C.; Montes, P.B.; Bustos, C.F.; Hoyuelos, X.P.; Vio, C.G. Effects of a combined program of behavioral modification techniques on decreasing disruptive behavior and increasing prosocial behavior in Chilean school children. Acta Colomb. Psicol. 2009, 12, 67–76. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Salmivalli, C.; Poskiparta, E. Making bullying prevention a priority in Finnish schools: The KiVa antibullying program. New Dir. Youth Dev. 2012, 133, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierman, K.L.; Coie, J.; Dodge, K.; Greenberg, M.; Lochman, J.; McMohan, R.; Pinderhughes, E. School Outcomes of Aggressive-Disruptive Children: Prediction from Kindergarten Risk Factors and Impact of the Fast Track Prevention Program. Agressive Behav. 2013, 39, 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Macazaga, A.M.; Rekalde, I.; Vizcarra, M.T. How to channel aggressiveness? A proposal of intervention through games and sports. Rev. Esp. Pedagog. 2013, 255, 263–276. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Oruche, U.M.; Gerkensmeyer, J.E.; Carpenter, J.S.; Austin, J.K.; Perkins, S.M.; Rawl, S.M.; Wright, E.R. Predicting Outcomes among Adolescents with Disruptive Disorders Being Treated in a System of Care Program. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 2013, 19, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jones, D.J.; Forehand, R.; Cuellar, J.; Parent, J.; Honeycutt, A.; Khavjou, O.; Gonzalez, M.; Anton, M.; Newey, G.A. Technology-Enhanced Program for Child Disruptive Behavior Disorders: Development and Pilot Randomized Control Trial. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2014, 43, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gómez, M.I.M. Programa de Intervención en Niños con Trastorno por Déficit de Atención con Hiperactividad (TDAH) y Familia. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Extremadura, Badajoz, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez, S.Y.; Rubio, E.L. Literary texts for the prevention of bullying. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Psychol. INFAD Rev. Psicol. 2014, 1, 313–318. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Burke, J.D.; Loeber, R. The Effectiveness of the Stop Now and Plan (SNAP) Program for Boys at Risk for Violence and Delinquency. Prev. Sci. 2015, 16, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, M.A.F. Desarrollo de la Competencia Social en Adolescentes Creación, Aplicación y Análisis del Programa El Pensamiento Prosocial en Entornos Educativos. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- González, B.M.; Cabrera, F.J.P. Evaluation of an Intervention Program to Reduce School Bullying and Disruptive Behavior. Acta Investig. Psicológ. 2015, 5, 1947–1959. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Rivas, E.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, J.; Ruiz-Palmero, J. Method for the educational treatment of disruptive behaviors in sports learning. Rev. Iberoam. Psicolog. Ejerc. Deporte 2015, 10, 225–234. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, M.C. Programa de Gestión y Fortalecimiento para la Resolución de Conflictos en los Estudiantes de 5° Grado de Educación Primaria de la I.E. N°10002 Urb. El Paraiso Chiclayo—Región Lambayeque. Bachelor’s Thesis, Pedro Ruiz Gallo National University, Lambayeque, Peru, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ávila, M.H.; Buscá, F. How conflicts are prevented and resolved in a physical education class. Tándem Didáct. Educ. Fís. 2016, 51, 61–66. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Cid, M.C.Q. Experiential pedagogy or experiential the Intensive program for young people. Rev. Educ. Soc. 2016, 22, 291–301. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Seguel, C.F.M.; Constanzo, A.X.Z. Factors associated with the interruption and maintenance of criminal behavior: A study with adolescents served by the Specialized Comprehensive Intervention Program of the Municipality of Osorno, Chile. Rev. Crim. 2017, 59, 49–64. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Katheleen, B.A.; Bebech, A.; Osiniak, K. Incorporating a Class-Wide Behavioral System to Decrease Disruptive Behaviors in the Inclusive Classroom. J. Cathol. Educ. 2018, 21, 205–214. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto, A.B. El programa Aprender a Convivir en Casa y su Influencia en la Mejora de la Competencia Social y la Reducción de Problemas de Conducta. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Granada, Granada, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Saad, M.A.E. The Effectiveness of a Life Skills Training Based on the Response to Intervention Model on Improving Disruptive Behavior of Preschool Children. Int. J. Psycho Educ. Sci. 2018, 7, 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Mouton, B.; Loop, L.; Stiévenart, M.; Roskam, I. Confident Parents for Easier Children A Parental Self-Efficacy Program to Improve Young Children’s Behavior. Educ. Sci. 2018, 8, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Puchaicela, B.A.O. Programa de Sensibilización Grupal para Disminuir el Bullying en los Estudiantes de Noveno Año del Paralelo b del Colegio de Bachillerato “27 de febrero”, de la ciudad de Loja. Bachelor’s Thesis, National University of Loja, Loja, Ecuador, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Juárez, G.P. Los Comportamientos Disruptivos en la Educación Física Escolar: Observación Sistemática de un Alumno de Educación Primaria. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Valladolid, Valladolid, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wora, A.H.; Salaam, N.; Leed, S.H.R.; Bergen-Cico, D.; Jennings-Bey, T.; Haygood El, A.; Rubinstein, R.A.; Lane, S.D. Culturally congruent mentorship can reduce disruptive behaviour among elementary school students: Results from a pilot study. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2018, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Dadds, M.R.; Sicouri, G.; Piotroska, P.J.; Collins, D.A.J.; Hawes, D.J.; Moul, C.; Lenroot, R.K.; Frick, P.J.; Anderson, V.; Kimonis, E.R.; et al. Keeping Parents Involved: Predicting Attrition in a Self-Directes, Online Program for Chilhood Conduct Problems. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2019, 48, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-López, A.; Rubio-Hernández, F.J.; Carbonell-Bernal, N. Effects of the application of an emotional intelligence program on the dynamics of bullying A pilot study. Rev. Psicol. Educ. J. Psychol. Educ. 2019, 14, 124–135. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Fuster-Guilló, A.; Pertegal-Felices, M.L.; Jimeno-Morenilla, A.; Azorín-López, J.; Rico-Soliveres, M.L.; Restrepo-Calle, F. Evaluating Impact on Motivation and Academic Performance of a Game-Based Learning Experience Using Kahoot. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goertz-Dorten, A.; Groth, M.; Detering, K.; Hellman, A.; Stadler, L.; Petri, B.; Doepfner, M. Efficacy of an Individualized Computer-Assisted Social Competence Training Program for Children with Oppositional Defiant Disorders/Conduct Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, J.; Cayuela, D.; López-Mora, C. Prosociality, Physical Education and Emotional Intelligence in School. J. Sport Health Res. 2019, 11, 17–32. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Ristkari, T.; Mishina, K.; Lehtola, M.-M.; Sourander, A.; Kurki, M. Public health nurses’ experiences of assessing disruptive behaviour in children and supporting the use of an Internet-based parent training programme. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2019, 3, 154–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reignier, V.R.; Zegarra, S.P.; García, L.G. CAPÍTULO 4: Propuesta de programa para la prevención del acoso escolar en Educación Primaria. In Variables Psicológicas y Educativas para la Intervención en el Ámbito Escolar; ASUNIVEP: Almeria, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pino, M.; Regal, M.T.G. Concept, types and etiology of disruptive behaviors in a Secondary School and High School from the teachers’ perspective. Rev. Psicolog. 2007, 28, 111–134. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Ovalles, A.; Macuare, M. Can the school environment be a space that generates violence in adolescents? Capítulo Criminol. 2009, 37, 103–109. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa, J.A.G.; Salazar, C.M. Detection of school violence in adolescents in physical education class. Rev. Iberoam. Psicol. Ejerc. Deporte 2015, 10, 41–47. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Alcaraz-Martínez, B.J.; Gómez-Mármol, A.; Valero-Valenzuela, A.; Esteban-Luis, R.; González-Víllora, S. Design and validation of an instrument for the observation of behaviors that alter coexistence in physical education. Estud. Educ. 2015, 35, 453–472. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Grau, M.P.; Prat, S.S. Actitudes, Valores y Normas en la Educación Física y el Deporte: Reflexiones y Propuestas Didácticas; INDE: Barcelona, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, M.; Escartí, A. Influence of parents and teachers on the goal orientation of adolescents and their intrinsic motivation in Physical Education. Rev. Psicol. Deporte 2006, 15, 23–35. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Alcaide, F.C.; del Rey Alamillo, R.; Ruiz, R.O. Conflictividad: Un estudio sobre problemas de convivencia escolar en Educación Primaria. Temas Educ. 2016, 22, 189–205. [Google Scholar]

- Leal-González, R.; Velásquez-Almarza, C.; de González, M.S. Asociación entre el clima familiar y las conductas disruptivas de los alumnos de primaria. Revista Internacional de Investigación y Formación Educativa 2019. Available online: https://www.ensj.edu.mx/revista-internacional-de-investigacion-y-formacion-educativa-riifeduc-enero-marzo-2019/ (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Mendieta, V.L.G.; Silva, M.T.J.; Goytizolo, R.C.S. Disciplina Positiva y las Conductas Disruptivas en los Niños del Aula de 5 Años del Nivel Inicial de la I.E “Santísimo Nombre de Jesús” del Distrito de San Borja. Bachelor’s Thesis, Instituto Pedagógico Nacional Monterrico, Lima, Peru, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva, S.V.; Díaz, E.C.; Quispe, W.V. School Disruption: A Good Pretext for Teacher Reflections. Apunt. Univ. Rev. Investig. 2019, 9, 85–102. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

| Database | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| Used in All Searches | “program” (“programa”), “disruptive behavior” (“conducta disruptiva”), “social inadaptation program” (“programa inadaptación social”), “disruptive behavior program”, (“programa conducta disruptiva”) |

| Additional Search Terms | |

| Google Scholar | “Anti-Social Behavior“, (“Conducta antisocial”), “Inadaptation“, (“Inadaptación”), “Personality disorders“, (“Trastornos de la personalidad”), “Social adaptation“, (“Adaptación social”), “Social alienation“, (“Alienación social”), “Juvenile delinquency“, (“Delincuencia juvenil”), “Anti-social behavior“, (“Comportamiento antisocial”), “Anti-social conduct“, (“Conducta antisocial”), “Social Inadaptation“, (“Inadaptación social”), “Educational Program“, (“Programa de Educación”) |

| Dialnet | “Anti-Social Behavior“, (“Conducta antisocial”), “Inadaptation“, (“Inadaptación”), “Personality disorders“, (“Trastornos de la personalidad”), “Social adaptation“, (“Adaptación social”), “Social alienation“, (“Alienación social”), “Juvenile delinquency“, (“Delincuencia juvenil”), “Anti-social behavior“, (“Comportamiento antisocial”), “Anti-social conduct“, (“Conducta antisocial”), “Social Inadaptation“, (“Inadaptación social”), “Educational Program“, (“Programa de Educación”) |

| Scopus | “Social maladjustment Program”, “Disruptive Behavior Program” |

| PubMed | “Social maladjustment Program”, “Disruptive Behavior Program” |

| Web of Science | “Social maladjustment Program”, “Disruptive Behavior Program” |

| ERIC Thesaurus | “Social maladjustment Program”, “Disruptive Behavior Program” |

| Author(S) and Year | Educational Stage | Location | Main Objective | Instrument(s) | Results * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of Turku (2006) [22] | Primary and Secondary Education | Finland, United Kingdom, Italy, Netherlands, Spain | To reduce the number of cases of school bullying through: Teacher training, helping families and educating through values, such as empathy. | - Training sessions for teachers - A guide for families - Interactive games and specific sessions for students - Follow-up questionnaires for students | ●●● |

| Martínez R. (2015) [23] | Primary and Secondary Education | Finland, United Kingdom, Italy, Netherlands, Spain | To reduce the number of cases of school bullying through: Teacher training, helping families and educating through values, such as empathy. | - Training sessions for teachers - A guide for families - Interactive games and specific sessions for students - Follow-up questionnaires for students | ●●● |

| Pichardo M.C. et al. (2008) [24] | Primary Education | Bolivia | To evaluate the effects of a social skills program, aimed at students in the first, second, and third year of primary education. | - Questionnaires | ●●● |

| Coronado A. (2009) [25] | Secondary Education | Undetermined | To improve the behavior of secondary education students who showed disruptive behavior. | - Semi-structured interviews - Observation - Reports and academic records | ●●● |

| Corsi E. et al. (2009) [26] | Primary Education | Chile | To evaluate the effectiveness of a behavioral intervention program (“the good behavior game”) in decreasing the frequency of disruptive behavior and increasing the frequency of prosocial behavior in the school setting. | Analysis: - Instructions - Verbal praise - Economy of tokens - Response cost Teacher training: - Role-play - Live modeling - Behavioral Test - Modeling - Self-modeling | ●●● |

| Salmivalli C. et al. (2012) [27] | Primary and Secondary Education | Finland, United Kingdom, Italy, Netherlands, Spain | To reduce the number of cases of school bullying through: Teacher training, helping families and educating through values such as empathy. | - Training sessions for teachers - A guide for families - Interactive games and specific sessions for students - Follow-up questionnaires for students | ●●● |

| Bierman K. L. et al. (2013) [28] | Primary and Secondary Education | United States | To identify the cognitive and behavioral contributions that lead to disruptive behavior during the school years and to evaluate the impact of the “Fast Track prevention program” in the school setting. | - PATHS (Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies) - Individual tutoring - Peer-to-peer work - Middle School Transition Program - Academic support in secondary school - After-school training for families and social skills teams for children - Education consultants - Participation questionnaires | ●○○ |

| Macazaga A. M. et al. (2013) [29] | Primary Education | Spain | To know what aggressiveness is and to learn how to manage and cope with it through the hidden curriculum and emotions. | Analysis: - Observation Startup: - Workshops - Construction of standards - Dissemination | ●●● |

| Oruche U. M. et al. (2013) [30] | Primary and Secondary Education | United States | To examine changes in personal strengths and family environment as predictors of behavioral and social functioning with adolescents who exhibit disruptive behavior. | - Questionnaires | ●●● |

| Jones D. J. et al. (2014) [31] | Infant and Primary Education | United States | To implement a pilot study of a technology-based family training program to help children with disruptive behavior in order to increase the commitment of low-income families and thereby improve children’s behavior. | - Mobile phone | ●●● |

| Montañez Gómez M. I. (2014) [32] | Primary Education | Spain | To develop and improve emotional intelligence competencies/skills and to offer home education guidelines. | - Questionnaires - Journal of sessions - Daily record sheet for the for daily life activities - Child Behavior Record Card | ●●○ |

| Yubero Jimenez S. et al. (2014) [33] | Primary and Secondary Education | Undetermined | To introduce children and adolescents to the analysis of peer relations and coexistence conflicts in educational centers through the reading of albums. | - Album | ●○○ |

| Burke J. D. et al. (2015) [34] | Primary Education | Canada | To reduce antisocial behavior in children aged 6-11. | - Questionnaires - Observation | ●●● |

| Fernández Durán M. A. (2015) [35] | Secondary Education | Spain | To increase the social competence of secondary school students in order to promote their personal and social development. | - Communication, emotional control, problem-solving, and social skills techniques - Questionnaires | ●●● |

| Mendoza González B. et al. (2015) [36] | Primary Education | Mexico | To examine the effectiveness of an intervention program based on the principles of Applied Behavioral Analysis to reduce children’s bullying behaviors in the school environment. | - Teacher training - Classroom rules - Social skills techniques - Motivation techniques -Emotional control techniques -Problem-solving skills techniques | ●●● |

| Sánchez-Rivas E. et al. (2015) [37] | Primary Education | Spain | To contribute to the improvement of sport learning processes in the school environment. | - Questionnaires - Interviews - Observation - Follow-up: Checklists and logbooks for observation, disruptive behavior observation sheets, ludogram | ●●● |

| Cherrés Sánchez M. (2018) [38] | Primary Education | Peru | To design a management and strengthening program to improve conflict resolution among students in the fifth grade of primary education. | - Bibliographic and newspaper sheets - Questionnaires | ●○○ |

| Hernández Ávila M. et al. (2016) [39] | Primary Education | Spain | To analyze teachers’ and students’ behavior in order to ascertain the degree of assimilation of the participatory or community model. | - Observation - “The traffic light” | ●●● |

| Quintas Cid M. C. (2016) [40] | Secondary Education | Austria | To change the situation of maladaptation or social exclusion of adolescents. | - Systemic therapy - Experiential pedagogy - Gestalt psychology | ●●● |

| Miranda Seguel C. F. et al. (2017) [41] | Secondary Education | Chile | To identify factors related to the interruption and maintenance of criminal behavior in adolescents. | - Statistical monitoring - Interviews (in-depth, with family models and the intervention team) | ●●○ |

| Aspiranti K. B. et al. (2018) [42] | Primary Education | Undetermined | To decrease inappropriate behaviors in primary education. | - “The color wheel” | ●●● |

| Benavides Nieto A. (2018) [43] | Infant Education | Spain | To increase children’s social competence in order to prevent potential behavioral problems. | - Questionnaires - Semi-structured interviews | ●●● |

| Eissa Saad M. A. (2018) [44] | Infant Education | United States | To examine the effectiveness of a program based on social skills training for the improvement of disruptive behaviors of children in early education. | - Instructions - Modeling - Social skills techniques (Role-play) - Feedback - Questionnaires | ●●● |

| Mouton B. et al. (2018) [45] | Infant Education | Undetermined | To analyze the effect of family self-efficacy thinking changes on the behavior of children in early childhood education. | - Observation - Questionnaires | ●●● |

| Obaco Puchaicela B. A. (2018). [46] | Secondary Education | Ecuador | To reduce bullying through a group awareness program. | - Questionnaires - Observation - Workshops | ●●● |

| Puebla Juárez G. (2018) [47] | Primary Education | Spain | To identify, describe, and record a particular student’s disruptive behaviors in physical education classes, language, mathematics, and recess time, and to present a proposal for an intervention that aims to reduce the frequency of occurrence of these unwanted behaviors within the classroom, particularly in the subject of physical education. | Research: - Observation (systemic and non-systemic) - Questionnaires Proposal for intervention: - Factsheets - Creation of standards - Self-observation technique - Positive reinforcement | ●○○ |

| Roca Pacheco R. M. (2018) [5] | Primary Education | Colombia | To identify and describe the problems affecting Primary School students. | - Surveys (structured with closed questions) | ●●● |

| Wora A. H. et al. (2018) [48] | Primary Education | United States | To examine the feasibility of implementing a pilot program based on culturally congruent mentoring, which aims to reduce the behaviors of elementary school students who exhibit repeated disruptive behavior. | - Observation - Questionnaires | ●●● |

| Dadds M. R. et al. (2019) [49] | All stages | Australia | To examine the risk factors for abandonment of free, evidence-based, self-directed parental programs. | - Questionnaires | ●●● |

| Díaz-López A. et al. (2019) [50] | Secondary Education | Spain | To evaluate the effect of a program based on emotional intelligence, on certain elements of school coexistence, bullying, as well as on motivation, empathy, and self-concept. | - Questionnaires | ●●● |

| Fuster-Guilló A. et al. (2019) [51] | University Education | Spain | To examine the benefits generated by the teaching-learning process through gamification in computer engineering degrees, and to analyze the impact on motivation and satisfaction, as well as on academic performance. | - Questionnaires -Surveys | ●●● |

| Goertz-Dorten A. et al. (2019) [52] | Primary Education | Germany | To decrease disruptive behaviors and behavioral problems in primary school students. | - Videos and cartoons - Social skills techniques (Role-play) - Questionnaires | ●●○ |

| González J. et al. (2019) [53] | Secondary Education | Spain | To analyze causal relationships between social interaction actions, the development of personality aspects, and the use of emotional intelligence skills in adolescents. | - Questionnaires | ●●● |

| Ristkari T. et al. (2019) [54] | Infant Education | Finland | To describe how the Public Nursing System uses and gains experience from a working model that combines a psychosocial tool to identify disruptive behavior in four-year-olds and a family training program with internet support through telephone coaching. | - Electronic questionnaire | ●●● |

| Romero Reignier V. et al. (2019) [55] | Primary Education | Undetermined | To present a proposal for intervention aimed at empowering Primary Education teachers to promote the emotional intelligence of their 5th and 6th-grade students in order to reduce bullying among young people and improving school coexistence in general. | - Questionnaires | ○○○ |

- * Results related to the main objective: ●●●: Expected; ●●○: Partially positive; ●○○: No desirable; ○○○: No result.

- It’s a new table reusing only some data in any publications.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martín Retuerto, D.; Ros Martínez de Lahidalga, I.; Ibañez Lasurtegui, I. Disruptive Behavior Programs on Primary School Students: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2020, 10, 995-1009. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe10040070

Martín Retuerto D, Ros Martínez de Lahidalga I, Ibañez Lasurtegui I. Disruptive Behavior Programs on Primary School Students: A Systematic Review. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2020; 10(4):995-1009. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe10040070

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartín Retuerto, Diego, Iker Ros Martínez de Lahidalga, and Irantzu Ibañez Lasurtegui. 2020. "Disruptive Behavior Programs on Primary School Students: A Systematic Review" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 10, no. 4: 995-1009. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe10040070

APA StyleMartín Retuerto, D., Ros Martínez de Lahidalga, I., & Ibañez Lasurtegui, I. (2020). Disruptive Behavior Programs on Primary School Students: A Systematic Review. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 10(4), 995-1009. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe10040070