The Relationship between Allostasis and Mental Health Patterns in a Pre-Deployment French Military Cohort

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

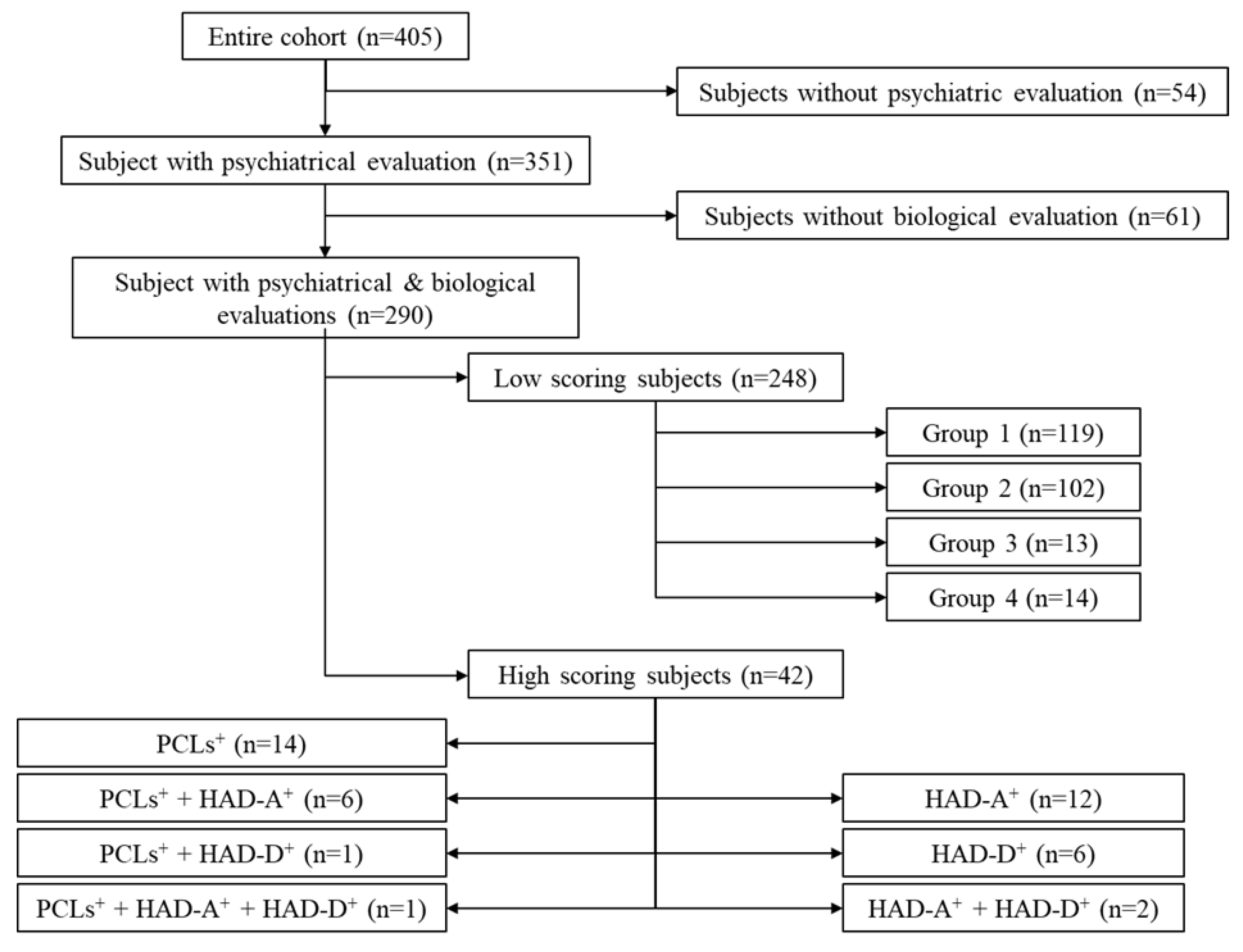

2.1. Population

2.2. Protocol

2.3. Biological Variables

2.4. Psychological Variables

2.4.1. Sociodemographic Evaluation

2.4.2. Psychopathological Evaluation

2.4.3. Psychological Evaluation

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Population Data

3.2. The HS Cohort

3.2.1. Biological Characterization of the HS Subgroup

3.2.2. Demographic Characterization of Pathological Subgroups

3.2.3. Psychological Characterization of HS Subgroups

3.2.4. Correlations

3.3. The LS Cohort

3.3.1. Biological Characterization of Clusters

3.3.2. Demographic Characterization of LS Subgroups

3.3.3. Psychological Characterization (Table 3 and Table 4)

3.3.4. Correlations

4. Discussion

4.1. High Scoring Subjects

4.1.1. Sub-Depressive HAD-D+ Subjects

4.1.2. Anxious HAD-A+ Subjects

4.1.3. Traumatized PCLs+ Subjects

4.2. Low Scoring Subjects

4.2.1. Subgroup Analysis

4.2.2. The Three Patterns

4.3. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Experimental HS Groups | n | PCLs | HAD-A | HAD-D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAD-D+ | 6 | 26.8 ± 4.3 | 7.5 ± 0.7 | 11.8 ± 0.5 |

| HAD-A+ | 12 | 30.9 ± 2.3 | 12.2 ± 0.4 | 6.0 ± 0.6 |

| HAD-D+ + HAD-A+ | 2 | 27.0 ± 10.0 | 11.5 ± 0.5 | 11.0 |

| PCLs+ | 14 | 50.2 ± 0.7 | 7.2 ± 0.7 | 5.2 ± 0.9 |

| PCLs+ + HAD-A+ | 6 | 55.2 ± 3.4 | 13.5 ± 0.7 | 6.2 ± 1.4 |

| PCLs+ + HAD-D+ | 1 | 53 | 8 | 11 |

| PCLs+ + HAD-D+ + HAD-A+ | 1 | 50 | 18 | 13 |

| Experimental LS Groups | n | PCLs | HAD-A | HAD-D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All LS subjects | 248 | 22.6 ± 0.4 | 5.2 ± 0.1 | 2.9 ± 0.1 |

| C1 | 119 | 22.8 ± 0.7 | 5.2 ± 0.2 | 3.1 ± 0.2 |

| C2 | 102 | 22.5 ± 0.7 | 5.1 ± 2.1 | 2.8 ± 0.2 |

| C3 | 13 | 24.0 ± 2.1 | 5.5 ± 0.7 | 2.6 ± 0.5 |

| C4 | 14 | 20.6 ± 1.6 | 5.5 ± 0.5 | 3.1 ± 0.5 |

References

- Hoge, C.W.; Terhakopian, A.; Castro, C.A.; Messer, S.C.; Engel, C.C. Association of posttraumatic stress disorder with somatic symptoms, health care visite, and absenteism among Iraq war veterans. Am. J. Psychiatry 2007, 164, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoge, C.W.; Auchterlonie, J.L.; Milliken, C.S. Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA 2006, 295, 1023–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cawkill, P.; Jones, M.; Fear, N.T.; Jones, N.; Fertout, M.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N. Mental health of UK Armed Forces medical personnel post-deployment. Occup. Med. 2015, 65, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hotopf, M.; Hull, L.; Fear, N.T.; Browne, T.; Horn, O.; Iversen, A.; Jones, M.; Murphy, D.; Bland, D.; Earnshaw, M.; et al. The health of UK military personnel who deployed to the 2003 Iraq war: A cohort study. Lancet 2006, 367, 1731–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, J.T.; Hauffa, R.; Jacobs, H.; Höllmer, H.; Gerber, W.D.; Zimmermann, P. Deployment-related stress disorder in german soldiers. Deutsches Ärzteblatt Int. 2012, 109, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Wal, S.J.; Vermetten, E.; Elbert, G. Long-term development of post-traumatic stress symptoms and associated risk factors in military service members deployed to Afghanistan: Results from the PRISMO 10-year follow-up. Eur. Psychiatry 2021, 64, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoge, C.W.; Castro, C.A.; Messer, S.C.; McGurk, D.; Cotting, D.I.; Koffman, R.L. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barrier to care. Am. J. Psychiatry 2004, 351, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoge, C.W.; Lesikar, S.E.; Guevara, R.; Lange, J.; Brundage, J.F.; Engel, C.C., Jr.; Messer, S.C.; Orman, D.T. Mental disorders among U.S. military personnel in the 1990s: Association with high levels of health care utilization and early military attrition. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 1576–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reijnen, A.; Rademaker, A.R.; Vermetten, E.; Geuze, E. Prevalence of mental health symptoms in Dutch military personnel returning from deployment to Afghanistan: A 2-year longitudinal analysis. Eur. Psychiatry 2015, 30, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.L.; Wilk, J.E.; Riviere, L.A.; McGurk, D.; Castro, C.A.; Hoge, C.W. Prevalence of mental health problems and functional impairment among active component and national guard soldiers 3 and 12 months following combat in Iraq. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 614–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulkin, J.; Sterling, P. Allostasis: A Brain-Centered, Predictive Mode of Physiological Regulation. Trends Neurosci. 2019, 42, 740–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selye, H. The Stress of Life; McGraw-Hill Book Company: New York, NY, USA, 1956; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Guidi, J.; Lucente, M.; Sonino, N.; Fava, G.A. Allostatic Load and Its Impact on Health: A Systematic Review. Psychother. Psychosom. 2021, 90, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fava, G.A.; McEwen, B.S.; Guidi, J.; Gostoli, S.; Offidani, E.; Sonino, N. Clinical characterization of allostatic overload. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 10, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, P.; Eyer, J. Allostasis: A new paradigm to explain arousal pathology. In Handbook of Life Stress, Cognition and Health; Fisher, S., Reason, J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1988; Volume 1, pp. 629–649. [Google Scholar]

- McEwen, B.S. Protection and damage from acute and chronic stress. Allostasis and allostatic overload and relevance to the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004, 1032, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: Central role of the brain. Physiol. Rev. 2007, 87, 873–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramsay, D.S.; Woods, M.C. Clarifying the Roles of Homeostasis and Allostasis in physiological Regulation. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 121, 225–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McEwen, B.S.; Karatsoreos, I.N. Sleep Deprivation and Circadian Disruption: Stress, Allostasis, and Allostatic Load. Sleep Med. Clin. 2015, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S.; Gianaros, P.J. Stress- and allostasis-induced brain plasticity. Annu. Rev. Med. 2011, 62, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grande, I.; Magalhães, P.V.; Kunz, M.; Vieta, E.; Kapczinski, F. Mediators of allostasis and systemic toxicity in bipolar disorder. Physiol. Behav. 2012, 106, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seplaki, C.L.; Goldman, N.; Weinstein, M.; Lin, Y.-H. How are biomarkers related to physical and mental well-being? J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med Sci. 2004, 59, B201–B217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nakamura, J.; Yakata, M. Clinical evaluation of the liquid-chromatographic determination of urinary free cortisol. Clin. Chem. 1983, 29, 847–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Petrides, J.S.; Gold, P.W.; Chrousos, G.P.; Deuster, P.A. Differential hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis reactivity to psychological and physical stress. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1999, 84, 1944–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danhof-Pont, M.B.; van Veen, T.; Zitman, F.G. Biomarkers in burnout: A systematic review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2011, 70, 505–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praticò, D.; Rokach, J.; Lawson, J.; FitzGerald, G.A. F2-isoprostanes as indices of lipid peroxidation in inflammatory diseases. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2004, 128, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschbacher, K.; O’Donovan, A.; Wolkowitz, O.M.; Dhabhar, F.S.; Su, Y.; Epel, E. Good stress, bad stress and oxidative stress: Insights from anticipatory cortisol reactivity. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2013, 38, 1698–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dimopoulos, N.; Piperi, C.; Psarra, V.; Lea, R.W.; Kalofoutis, A. Increased plasma levels of 8-iso-PGF2α and IL-6 in an elderly population with depression. Psychiatry Res. 2008, 161, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatsoreos, I.N.; McEwen, B.S. Psychobiological allostasis: Resistance, resilience and vulnerability. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2011, 15, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallingford, J.K.; Deurveilher, S.; Currie, R.W.; Fawcette, J.P.; Semba, K. Increases in mature brain-derived neurotrophic factor protein in the frontal cortex and basal forebrain during chronic sleep restriction in rats: Possible role in initiating allostatic adaptation. Neuroscience 2014, 277, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yulug, B.; Ozan, E.; Gönül, A.S.; Kilic, E. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor, stress and depression: A minireview. Brain Res. Bull. 2009, 78, 267–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horesh, N.; Klomek, A.B.; Apter, A. Stressful life events and major depressive disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2008, 160, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C. The effects of stressfull life events on depression. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1997, 48, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epel, E.S.; Crosswell, A.D.; Mayer, S.E.; Prather, A.A.; Slavich, G.M.; Puterman, E.; Mendes, W.B. More than a feeling: A unified view of stress measurement for population science. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2018, 49, 146–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjelland, I.; Dahl, A.A.; Haug, T.T.; Neckelmann, D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale An updated literature review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002, 52, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brennan, C.; Worrall-Davies, A.; McMillan, D.; Gilbody, S.; House, A. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: A diagnostic meta-analysis of case-finding ability. J. Psychosom. Res. 2010, 69, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed.; American Psychiatric Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard, E.B.; Jones-Alexander, J.; Buckley, T.C.; Forneris, C.A. Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL). Behav. Res. Ther. 1996, 34, 669–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terhakopian, A.; Sinaii, N.; Engel, C.C.; Schnurr, P.P.; Hoge, C.W. Estimating population prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder: An example using the PTSD checklist. J. Trauma Stress 2008, 21, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerclé, A.; Gadéa, C.; Hartmann, A.; Lourel, M. Typological and factor analysis of the perceived stress measure by using the PSS scale. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 58, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collange, J.; Bellinghausen, L.; Chappé, J.; Saunder, L.; Albert, E. Perceived stress: When does it become a risk factor for anxiodepressive disorders? Arch. Mal. Prof. Environ. 2013, 74, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagby, R.M.; Parker, J.D.A.; Taylor, G.J. The twenty-item Toronto alexithymia scale–I. Item selection and cross validation of the factor structure. J. Psychosom. Res. 1994, 38, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagby, R.M.; Taylor, G.J.; Parker, J.D.A. The Twenty-Item Toronto Alexithymia Scale–II. Convergent, discriminant, and concurrent validity. J. Psychosom. Res. 1994, 38, 33–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loas, G.; Otmani, O.; Verrier, A.; Fremaux, D.; Marchand, M.-P. Factor analysis of the French Version of the 20 items Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20). Psychopathology 1996, 29, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilbaud, O.; Loas, G.; Corcos, M.; Speranza, M.; Stephan, P.; Perez-Diaz, F.; Venisse, J.L.; Guelfi, J.D.; Bizouard, P.; Lang, F.; et al. L’alexithymie dans les conduites de dépendance et chez le sujet sain: Valeur en population française et francophone [Alexithymia in addictive behaviours and in healthy subjects: Value in French and French-speaking populations]. Anna. Méd.-Psychol. 2002, 160, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, C. Manual for the State-Trait-Anxiety Inventory: STAI (Form Y); Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Bruchon-Schweitzer, M.; Dantzer, R. Introduction à la Psychologie de la Santé; PUF: Paris, France, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P. Maslach Burnout Inventory; Mind Garden: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lourel, M.; Guéguen, N.; Mouda, F. L’évaluation du burnout de Pines: Adaptation et validation en version française de l’instrument Burnout Measure Short version (BMS-10). Prat. Psychol. 2007, 13, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatzias, A.; Chouliara, Z.; Power, K.; Swanson, V. Predicting general well-being from self-esteem and affectivity: An exploratory study with Scottish adolescents. Qual. Life Res. 2006, 15, 1143–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caci, H.; Baylé, F.J. L’échelle d’affectivité positive et d’affectivité négative. Première traduction en français [Positive and negative affects scale. First french translation]. In Proceedings of the Congrès de l’Encéphale, Paris, France, 2007; pp. 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banks, M.H. Validation of the general health questionnaire in a young community sample. Psychol. Med. 1983, 13, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pariente, P.D.; Guelfi, J.D. Inventaires d’auto-évaluation de la psychopathologie chez l’adulte. Are–B partie: Inventaires multidimensionnels [Self-report symptom inventories for adults: I. Multidimensional questionnaires]. Eur. Psychiatry 1990, 5, 49–75. [Google Scholar]

- Golderg, D.; Williams, P. A User’s Guide to the General Health Questionnaire; NFER-Nelson: Windsor, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Murtagh, F.; Legendre, P. Ward’s Hierarchical Agglomerative Clustering Method: Which Algorithms Implement Ward’s Criterion? J. Classif. 2014, 31, 274–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Packnett, E.R.; Elmasry, H.; Toolin, C.F.; Cowan, D.N.; Boivin, M.R. Epidemiology of Major Depressive Disorder Disability in the US Military: FY 2007-2012. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2017, 205, 672–678. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, P.-T.; Lee, Y.; Lin, P.-Y. Age-associated decrease in serum glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor levels in patients with major depressive disorder. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 40, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunoni, A.R.; Lopes, M.; Fregni, F. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical studies on major depression and BDNF levels: Implications for the role of neuroplasticity in depression. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008, 11, 1169–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishi, T.; Yoshimura, R.; Ikuta, T.; Iwata, N. Brain-cerived neurotrophic factor and major depressive disorder: Evidence from meta-analyses. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 8, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, B.-H.; Kim, H.; Park, S.-H.; Kim, Y.-K. Decreased plasma BDNF level in depressive patients. J. Affect. Disord. 2007, 101, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molendijk, M.L.; Spinhoven, P.; Polak, M.; Bus, B.A.A.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Elzinga, B.M. Serum BDNF concentrations as peripheral manifestations of depression: Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analyses on 179 associations (N = 9484). Mol. Psychiatry 2013, 19, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, E.; Hashimoto, K.; Okamura, N.; Koike, K.; Komatsu, N.; Kumakiri, C.; Nakazato, M.; Watanabe, H.; Shinoda, N.; Okada, S.-I.; et al. Alterations of serum levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in depressed patients with or without antidepressants. Biol. Psychiatry 2003, 54, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolkowitz, O.M.; Wolf, J.; Shelly, W.; Rosser, R.; Burke, H.M.; Lerner, G.K.; Reus, V.I.; Craig Nelson, J.; Epel, E.S.; Mellon, S.H. Serum BDNF levels before treatment predict SSRI response in depression. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 35, 1623–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lang, U.E.; Hellweg, R.; Gallinat, J. BDNF serum concentrations in healthy volunteers are associated with depression-related personality traits. Neuropsychopharmacology 2004, 29, 795–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terracciano, A.; Lobina, M.; Piras, M.G.; Mulas, A.; Cannas, A.; Meirelles, O.; Sutin, A.R.; Zonderman, A.B.; Uda, M.; Crisponi, L.; et al. Neuroticism, depressive symptoms, and serum BDNF. Psychosom. Med. 2011, 73, 638–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Trajkovska, V.; Vinberg, M.; Aznar, S.; Knudsen, G.M.; Kessing, L.V. Whole blood BDNF levels in healthy twins discordant for affective disorder: Association to life events and neuroticism. J. Affect. Disord. 2008, 108, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendler, K.S.; Karkowski, L.M.; Prescott, C.A. Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 1999, 156, 837–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, B.; Cui, R. The Effects of Psychological Stress on Depression. Curr. neuropharmacol. 2015, 13, 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Alta’ee, A.H.; Al-Khayat, T.H.; Al-Ameedy, W.A.; Majeed, L.A. Oxidative stress in post-traumatic stress disorders for terror attack victims in Iraq. Babylon Univ. Pure Appl. Sci. 2012, 22, 408–416. [Google Scholar]

- Atli, A.; Bulut, M.; Bez, Y.; Kaplan, I.; Özdemir, P.G.; Uysal, C.; Selçuk, H.; Sir, A. Altered lipid peroxidation markers are related to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and not trauma itself in earthquake survivors. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2015, 266, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels, L.; Schulte-Vels, T.; Schick, M.; O’Gorman, R.L.; Zeffiro, T.; Hasler, G.; Mueller-Pfeiffer, C. Prefrontal GABA and glutathione imbalance in posttraumatic stress disorder: Preliminary findings. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2014, 224, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceprnja, M.; Derek, L.; Unić, A.; Blazev, M.; Fistonić, M.; Kozarić-Kovacić, D.; Franić, M.; Romić, Z. Oxidative stress markers in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder. Coll. Antropol. 2011, 35, 1155–1160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Morris, M.C.; Compas, B.E.; Garber, J. Relations among posttraumatic stress disorder, comorbid major depression, and HPA function: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 32, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Galatzer-Levy, I.R.; Ma, S.; Statnikov, A.; Yehuda, R.; Shalev, A.Y. Utilization of machine learning for prediction of post-traumatic stress: A re-examination of cortisol in the prediction and pathways to non-remitting PTSD. Transl. Psychiatry 2017, 7, e1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steudte-Schmiedgen, S.; Stalder, T.; Schönfeld, S.; Wittchen, H.-U.; Trautmann, S.; Alexander, N.; Miller, R.; Kirschbaum, C. Hair cortisol concentrations and cortisol stress reactivity predict PTSD symptom increase after trauma exposure during military deployment. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015, 59, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radley, J.J.; Kabbaj, M.; Jacobson, L.; Heydendael, W.; Yehuda, R.; Herman, J.P. Stress risk factors and stress-related pathology: Neuroplasticity, epigenetics and endophenotypes. Stress 2011, 14, 481–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bernat, J.A.; Ronfeldt, H.M.; Calhoun, K.S.; Arias, I. Prevalence of traumatic events and peritraumatic predictors of posttraumatic stress symptoms in a nonclinical sample of college students. J. Trauma Stress 1998, 11, 645–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeardMann, C.A.; Smith, T.C.; Smith, B.; Wells, T.S.; Ryan, M.A.K. Baseline self-reported functional health and vulnerability to post-traumatic stress disorder after combat deployment: Prospective US military cohort study. BMJ 2009, 338, b1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, T.C.; Ryan, M.A.; Wingard, D.L.; Slymen, D.J.; Sallis, J.F.; Kritz-Silverstein, D. New onset and persistent symptoms of postraumatic stress disorder self-reported after deployment and combat exposure: Prospective population based US military cohort study. BMJ 2008, 336, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lipton, S.A.; Choi, Y.-B.; Pan, Z.-H.; Lei, S.Z.; Chen, H.-H.V.; Sucher, N.J.; Loscalzo, J.; Singel, D.J.; Stamler, J.S. A redox-based mechanism for the neuroprotective and neurodestructive effects of nitric oxide and related nitroso-compounds. Nature 1993, 364, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, N.; Workman, J.L.; Lee, T.T.; Innala, L.; Viau, V. Sex differences in the HPA axis. Compr. Physiol. 2014, 4, 1121–1155. [Google Scholar]

- Bangasser, D.A.; Eck, S.R.; Telenson, A.M.; Salvatore, M. Sex differences in stress regulation of arousal and cognition. Physiol. Behav. 2018, 187, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirschbaum, C.; Pirke, K.-M.; Hellhammer, D.H. Preliminary evidence for reduced cortisol responsivity to psychological stress in women using oral contraceptive medication. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1995, 20, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, A.B.; Huffman, A.H.; Bliese, P.D.; Castro, C.A. The impact of deployment length and experience on the well-being of male and female soldiers. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2005, 10, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckner, M.E.; Main, L.; Tait, J.; Martin, B.J.; Conkright, W.R.; Nindl, B.C. Circulating biomarkers associated with performance and resilience during military operationnel stress. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2021, 4, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Experimental Group | n | U-CORT | B-CORT | B-BDNF | U-PGF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factorial analysis | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | |||

| High scoring subjects (HS) | 42 | 61.31 ± 10.76 q | 605.24 ± 23.03 | 13.20 ± 1.11 | 22,683 ± 4375 # |

| HAD-D+ | 6 | 40.76 ± 8.24 | 579.83 ± 54.20 | 8.07 ± 2.33 * | 23,796 ± 15,482 |

| HAD-A+ | 12 | 50.90 ± 9.42 | 607.33 ± 45.87 | 15.41 ± 1.68 | 20,272 ± 6726 |

| HAD-D+ + HAD-A+ | 2 | 37.81 ± 0.26 | 540.50 ± 101.50 | 20.61 ± 13.05 t | 11,235 ± 645 |

| PCLs+ | 14 | 74.21 ± 31.00 * | 624.37 ± 47.66 | 11.44 ± 1.66 | 30,344 ± 8932 * |

| PCLs+ + HAD-A+ | 6 | 72.41 ± 11.90 t | 605.50 ± 41.58 | 13.18 ± 1.63 | 17,193 ± 10,782 |

| PCLs+ + HAD-D+ | 1 | 44.53 | 450 | 17.40 | 11,270 |

| PCLs+ + HAD-D+ + HAD-A+ | 1 | 66.19 | 748 | 23.45 | 4944 |

| Low scoring subjects (LS) | 248 | 50.55 ± 1.71 q | 597.74 ± 10.26 | 13.37 ± 0.35 | 15,212 ± 1353 # |

| C1 | 119 | 36.80 ± 1.32 | 578.85 ± 9.12 | 11.10 ± 0.32 | 10,523 ± 908 |

| C2 | 102 | 68.49 ± 2.69 *** | 556.25 ± 10.89 | 16.56 ± 0.61 *** | 11,678 ± 931 |

| C3 | 13 | 49.38 ± 8.85 | 576.08 ± 46.36 | 11.36 ± 0.97 | 96,018 ± 2797 *** |

| C4 | 14 | 37.89 ± 7.27 | 1080.64 ± 36.20*** | 11.25 ± 0.54 | 5787 ± 1506 |

| Experimental Group | Gender (M/F) | Age | Family (Yes/No) | Tobacco Use (Yes/No) | Length of Service | Previous Deployment (Yes/No) | Number of Deployments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High scoring subjects (HS) | 38/4 | 29.9 ± 1.1 | 26/15 | 14/22 | 9.0 ± 1.1 | 29/12 | 3.9 ± 0.4 |

| HAD-D+ | 6/0 | 26.5 ± 2.9 | 3/3 | 3/1 | 5.8 ± 2.0 | 4/2 | 3.5 ± 1.5 |

| HAD-A+ | 10/2 | 30.7 ± 1.9 | 8/4 | 4/7 | 10.8 ± 1.9 | 10/2 | 3.3 ± 0.8 |

| HAD-D+ + HAD-A+ | 2/0 | 22.0 ± 1.0 | 1/1 | 0/2 | 3.0 ± 2.0 | 1/1 | 4 |

| PCLs+ | 12/2 | 28.4 ± 1.7 | 8/6 | 5/7 | 8.9 ± 1.6 | 10/4 | 4.9 ± 0.7 |

| PCLs+ + HAD-A+ | 6/0 | 30.7 ± 4.7 | 5/1 | 1/4 | 11.7 ± 4.6 | 3/3 | 4.0 ± 1.4 |

| PCLs+ + HAD-D+ | 1/0 | 33 | 0/1 | 1/0 | 13 | 1/0 | 2 |

| PCLs+ + HAD-D+ + HAD-A+ | 1/0 | - | - | 0/1 | - | - | - |

| Low scoring subjects (LS) | 212/35 | 29.9 ± 0.4 | 133/113 | 89/133 | 9.3 ± 0.4 | 166/81 | 3.7 ± 0.2 |

| C1 | 103/16 | 30.0 ± 0.6 | 58/61 | 50/53 | 9.3 ± 0.6 | 82/37 | 3.8 ± 0.3 |

| C2 | 98/4 | 30.4 ± 0.7 | 61/41 t | 30/62 | 9.8 ± 0.7 | 70/31 | 3.7 ± 0.3 |

| C3 | 11/2 | 29.5 ± 1.9 | 10/3 t | 8/4 | 9.3 ± 1.6 | 9/4 | 3.0 ± 0.4 |

| C4 | 0/13 *** | 25.6 ± 0.8 * | 5/8 | 1/11 | 5.1 ± 0.7 * | 5/9 * | 1.6 ± 0.4 |

| Experimental Group | Size | PSS | TAS | STAI-T | STAI-S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High scoring subjects (HS) | 42 | 39.9 ± 0.8 *** | 43.3 ± 1.3 *** | 43.3 ± 1.3 *** | 40.1 ± 1.5 *** |

| HAD-D+ | 6 | 38.8 ± 4.0 * | 31.2 ± 2.8 ** | 41.2 ± 4.6 t | 37.4 ± 5.4 |

| HAD-A+ | 12 | 39.7 ± 1.2 *** | 44.2 ± 2.1 ** | 46.2 ± 2.4 *** | 41.4 ± 2.7 *** |

| HAD-D+ + HAD-A+ | 2 | 38.5 ± 3.5 | 46.0 ± 1.0 | 46.5 ± 1.5 * | 47.0 ± 3.0 ** |

| PCLs+ | 14 | 39.6 ± 1.3 *** | 44.2 ± 1.8 ** | 39.0 ± 2.2 * | 35.7 ± 2.7 |

| PCLs+ + HAD-A+ | 6 | 42.7 ± 2.4 *** | 49.5 ± 3.8 *** | 48.5 ± 2.8 *** | 48.5 ± 2.5 *** |

| PCLs+ + HAD-D+ | 1 | 38 | 51 | 41 | 30 |

| PCLs+ + HAD-D+ + HAD-A+ | 1 | 42 | 38 | 41 | 45 |

| Low scoring subjects (LS) | 248 | 32.9 ± 0.4 | 38.8 ± 0.4 | 34.5 ± 0.5 | 32.2 ± 0.5 |

| C1 | 119 | 33.0 ± 0.6 | 38.9 ± 0.6 | 35.3 ± 0.7 | 31.6 ± 0.7 |

| C2 | 102 | 33.0 ± 0.5 | 38.5 ± 0.7 | 33.4 ± 0.7 t | 32.0 ± 0.6 |

| C3 | 13 | 28.5 ± 2.0 * | 38.9 ± 1.7 | 32.5 ± 2.0 | 30.7 ± 1.7 |

| C4 | 14 | 34.8 ± 1.5 | 40.6 ± 1.6 | 36.9 ± 2.1 | 38.4 ± 3.1 * |

| Experimental Group | Size | BMS | PANAS-NA | PANAS-PA | GHQ28 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High scoring subjects (HS) | 42 | 27.6 ± 1.1 *** | 25.0 ± 1.1 *** | 37.1 ± 1.0 | 28.6 ± 1.9 *** |

| HAD-D+ | 6 | 22.7 ± 5.3 | 18.6 ± 2.1 | 33.63.8 t | 24.0 ± 6.0 * |

| HAD-A+ | 12 | 26.6 ± 1.2 *** | 26.7 ± 1.2 *** | 34.9 ± 1.7 * | 26.6 ± 2.8 *** |

| HAD-D+ + HAD-A+ | 2 | 25.5 ± 2.5 | 28.5 ± 5.5 ** | 32.0 ± 4.0 | 31.5 ± 0.5 ** |

| PCLs+ | 14 | 28.4 ± 1.5 *** | 22.4 ± 1.9 *** | 38.2 ± 1.6 | 27.9 ± 3.9 *** |

| PCLs+ + HAD-A+ | 6 | 32.7 ± 3.5 *** | 31.8 ± 3.4 *** | 42.2 ± 2.2 | 36.5 ± 3.3 *** |

| PCLs+ + HAD-D+ | 1 | 33 | 19 | 41 | 28 |

| PCLs+ + HAD-D+ + HAD-A+ | 1 | - | 32 | 41 | 37 |

| Low scoring subjects (LS) | 248 | 18.0 ± 0.5 | 17.7 ± 0.3 | 38.6 ± 0.4 | 15.4 ± 0.5 |

| C1 | 119 | 18.6 ± 0.8 | 17.8 ± 0.4 | 38.4 ± 0.4 | 14.6 ± 0.7 |

| C2 | 102 | 17.3 ± 0.8 | 17.1 ± 0.4 | 38.6 ± 0.5 | 16.8 ± 0.8 * |

| C3 | 13 | 15.0 ± 2.1 | 18.5 ± 1.4 | 40.8 ± 1.2 | 12.3 ± 2.8 |

| C4 | 14 | 20.0 ± 1.8 | 20.8 ± 1.0 * | 38.3 ± 1.1 | 15.3 ± 1.6 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trousselard, M.; Claverie, D.; Fromage, D.; Becker, C.; Houël, J.-G.; Benoliel, J.-J.; Canini, F. The Relationship between Allostasis and Mental Health Patterns in a Pre-Deployment French Military Cohort. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2021, 11, 1239-1253. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe11040090

Trousselard M, Claverie D, Fromage D, Becker C, Houël J-G, Benoliel J-J, Canini F. The Relationship between Allostasis and Mental Health Patterns in a Pre-Deployment French Military Cohort. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2021; 11(4):1239-1253. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe11040090

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrousselard, Marion, Damien Claverie, Dominique Fromage, Christel Becker, Jean-Guillaume Houël, Jean-Jacques Benoliel, and Frédéric Canini. 2021. "The Relationship between Allostasis and Mental Health Patterns in a Pre-Deployment French Military Cohort" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 11, no. 4: 1239-1253. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe11040090

APA StyleTrousselard, M., Claverie, D., Fromage, D., Becker, C., Houël, J.-G., Benoliel, J.-J., & Canini, F. (2021). The Relationship between Allostasis and Mental Health Patterns in a Pre-Deployment French Military Cohort. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 11(4), 1239-1253. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe11040090