Creating Value in Non-Profit Sports Organizations: An Analysis of the DART Model and Its Performance Implications

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis

2.1. Value Creation and Cocreation

2.2. Performance of Sports Organizations

2.3. Hypotheses and Conceptual Model

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Context

3.2. Dimension Definition and Operationalization

3.3. Instrument

3.4. Procedure

4. Statistical Analyses

4.1. Measurement Models

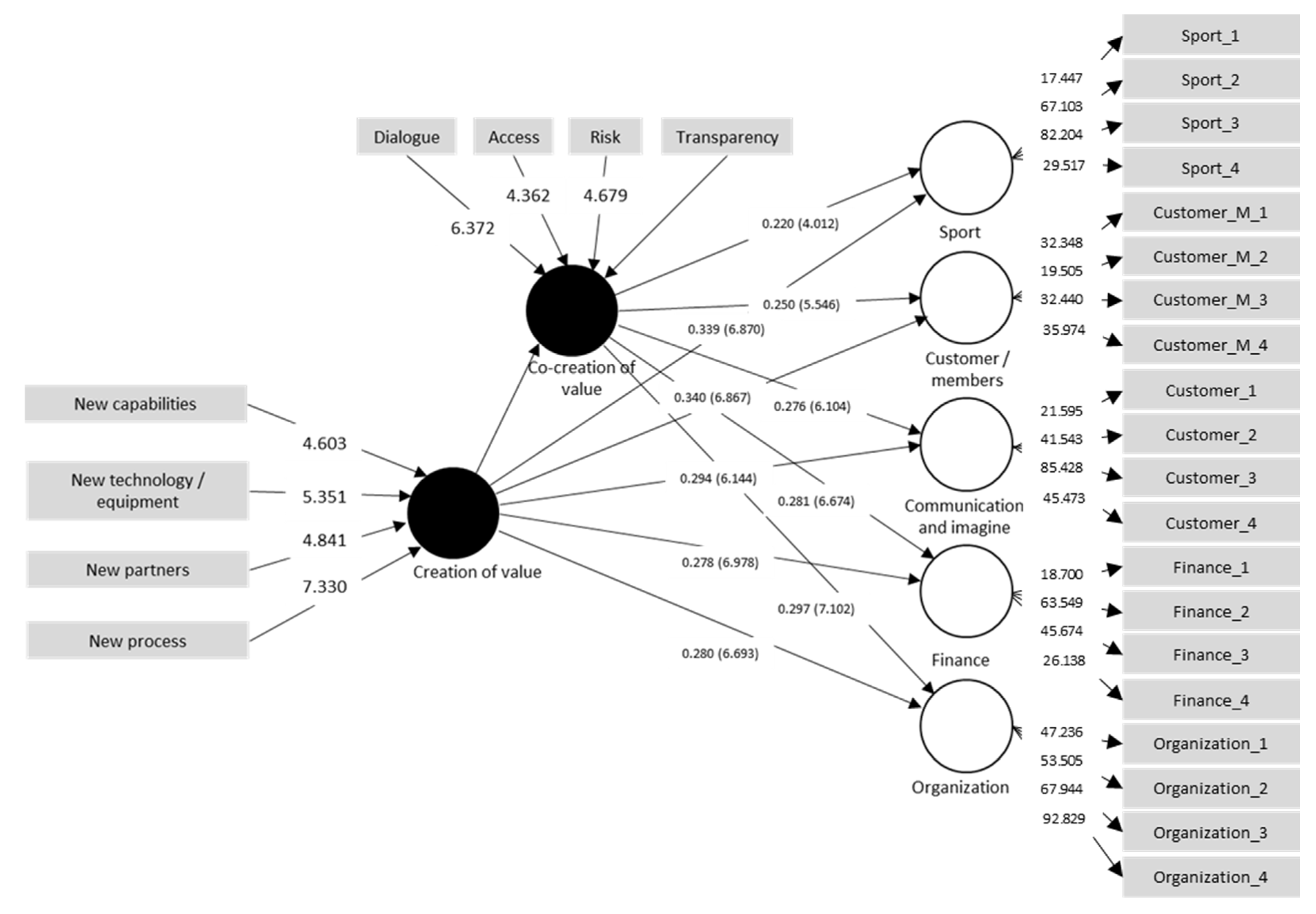

4.2. Structural-Model Analysis

4.3. Test for Mediation

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Implications

- (i)

- This study improves the theories on value creation and cocreation in sports organizations. Specifically, value creation in Colombian soccer clubs takes place through new capabilities and new processes. The main common element in these clubs is the ability of individuals to create or improve products, services, or activities, which is in line with the findings reported in [69,70]. It is essential that professionals recognize the pivotal role of value creation in driving organizational success. Therefore, they should prioritize strategies that enhance customer/member value, sports performance, communication, and financial stability. This study is consistent with previous research, which emphasized the economic benefits that sports organizations can obtain through value creation. Moreover, practitioners should be aware that value-creation initiatives not only contribute to organizational performance, but also have the potential to attract favorable financial support, program participation, and physical outcomes in sports. By leveraging value creation for economic gain, NPSOs can enhance their financial viability and long-term sustainability.

- (ii)

- The study shows that value creation by sports clubs has a positive impact on the performance dimensions of soccer clubs, and that new services are sources of income, strategic alliances, improvements in organizational image, and more efficient administrative processes. All of this confirms previous findings in relation to the impact of value creation on the performance of sports organizations [1,5,9,45]. The findings highlight the mediating role of value cocreation in the relationship between value creation and organizational performance. This implies that organizations should actively involve customers/members, stakeholders, and other interested parties in their cocreation processes. By encouraging collaboration and shared decision making, NPSOs can improve their performance, tailoring strategies to address specific performance aspects. This study identifies various aspects that contribute to organizational performance, such as sport, customers/members, communication, image, finance, and organization. To optimize performance, organizations must assess their strengths and weaknesses in each aspect and develop targeted strategies to improve the areas that have the greatest impact on performance.

- (iii)

- The existence of value cocreation in Colombian soccer clubs is demonstrated, which is a contribution to the body of research presented in [33,34]. Among other activities, these clubs hold formal and informal discussions for new service-design processes and to solve mutual problems using communication channels, as described in [26,27,71]. This study shows that the most positive effects of value-creation processes are on the customers/members of amateur soccer clubs. This highlights the importance of understanding and meeting customer/member needs in creative and innovative ways. By delivering value and building strong relationships with their target audience, NPSOs can attract new customers/members, ensure their loyalty, and receive ongoing support.

- (iv)

- This study proposes a conceptual model validated by the PLS-SEM method, thus contributing knowledge to the field of value creation and cocreation in Colombian soccer clubs, which are fragile and precarious sports organizations [21,22]. The study also provides valuable and unique information about the benefits of creating value in amateur soccer clubs in developing countries [72,73] to positively affect the dimensions of organizational performance. Furthermore, this study is one of the first attempts to provide empirical evidence linking value creation, cocreation, and implementation in sports organizations in the South American context.

5.2. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Description of Constructs

| First-Order Constructs | Original Dimensions | Adapted Dimensions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| The author of [60] conducted research on value cocreation in Malaysian telecommunication companies. | Dialogue | Use different communication channels to hold dialogue sessions with consumers | The club uses different communication channels to engage in dialogue with consumers |

| Hold frequent dialogue sessions with consumers | The club frequently holds dialogue sessions with consumers | ||

| Involve internal parties in dialogue sessions with consumers | The club involves its internal staff in dialogue sessions with consumers | ||

| Involve external parties in dialogue sessions with consumers | The club involves external entities in dialogue sessions with consumers | ||

| Recognize consumers’ experiences with the service or product | The club recognizes consumers’ experiences with its sports products | ||

| Emphasize employees’ efforts in dealing with individual consumers | The club emphasizes employees’ efforts in dealing with each consumer | ||

| Access | Offer consumers the opportunity to participate in the service- or product-design process | The club offers consumers the opportunity to participate in the design process of their sports products | |

| Offer consumers the opportunity to participate in the service- or product-development process | The club offers consumers the opportunity to participate in the process of making their sports products | ||

| Offer consumers the opportunity to participate in the service- or product-pricing process | The club offers consumers the opportunity to participate in the process of setting the price of their sports products | ||

| Place more emphasis on providing consumer experiences than on the service or product ownership | The club emphasizes the delivery of consumer experiences based on the properties of its sports products | ||

| Provide consumers with all the necessary information related to the service or product | The club provides consumers with all the necessary information related to its sports products | ||

| Risk | Inform consumers of the potential risks of the service or product offered | The club informs consumers of the potential risks of the sports products offered | |

| Inform consumers about the limitations and capabilities of the firm | The club informs consumers about its capabilities and limitations | ||

| Recognize the changing dynamics of consumer needs | The club recognizes the changing dynamics of consumer needs | ||

| Accept consumers’ complaints about the service or product offered | The club accepts consumers’ complaints about the sports products offered | ||

| Assume all risk-related responsibilities | The club assumes all the responsibility for the risks associated with their sports products | ||

| Transparency | Provide consumers with clear information about the service or product | The club provides consumers with clear information about its sports products | |

| Disclose price-related information to consumers | The club discloses the prices of its sports products to consumers | ||

| Benefit from information symmetry between consumers and the firm | The club benefits from the exchange of information with its consumers | ||

| Build trust among consumers through transparent information | The club builds consumer trust through transparent information | ||

| Provide consumers with up-to-date information | The club provides consumers with up-to-date information | ||

| The authors of [64] studied value creation in the manufacturing industry | New skills | Our employees receive ongoing training to develop new skills | The club’s employees receive ongoing training to develop new skills |

| Our employees have up-to-date knowledge and skills compared to our direct competitors | The club’s employees have up-to-date knowledge and skills compared to our direct competitors | ||

| We are constantly reflecting on which new skills are needed to adapt to changing market requirements | The club is constantly reflecting on the need for new skills to adapt to market changes | ||

| New technologies | We keep our firm’s technical resources up to date | The club keeps its technological resources up to date | |

| Our technical equipment is very innovative compared to that of our competitors | The club’s technological equipment is very innovative compared to that of its competitors | ||

| We regularly use new technology to expand our product-and-service portfolio | The club uses new technology to expand its product and service portfolio | ||

| New partners | We are constantly looking for new partners | The club is constantly looking for new business partners | |

| We regularly take advantage of opportunities to integrate new partners into our processes | The club regularly takes advantage of opportunities to integrate new partners into its processes | ||

| We regularly evaluate the potential benefits of outsourcing | The club regularly evaluates the potential benefits of outsourcing | ||

| New partners regularly help us develop our business model | New partners regularly help strengthen the club’s business model | ||

| New process | We have recently made significant improvements to our internal processes | The club has recently made significant improvements to its internal processes | |

| We implement innovative procedures and processes to manufacture our products | The club implements innovative processes to develop its sports products | ||

| We regularly assess our existing processes and make significant changes when necessary | The club regularly evaluates its existing processes and makes significant changes when necessary | ||

| The authors of [62] proposed a method to quantitatively assess organizational performance in the governing bodies of the French-speaking community | Elite sport | Obtain international sport results | The club seeks to obtain sports results (Sport_1) |

| Increase athletes’ participation in international competitions | The club increases the participation of its athletes in international competitions (Sport_2) | ||

| Improve sports services for athletes | The club improves services for its athletes (Sport_3) | ||

| Increase sports activities for members | The club increases sports activities for its members (Sport_4) | ||

| Customers | Preserve sporting values in society | The club preserves sporting values in society (Customer_M_1) | |

| Improve the provision of non-sports services to members | The club improves the provision of non-sports services to its members (Customer_M_2) | ||

| Attract members | The club attracts new members (Customer_M_3) | ||

| Build members’ loyalty | The club builds loyalty among its members (Customer_M_4) | ||

| Communication and image | Promote a positive image of their sport in the media | The club promotes a positive image of soccer in the media (Com_Image_1) | |

| Promote a positive image of their sport among members | The club promotes a positive image of soccer among its members (Com_Image_2) | ||

| Improve internal communication among members and clubs | The club improves internal communication with its members (Com_Image_3) | ||

| Improve tracking of internal communication with members | The club improves the tracking of internal communication with its members (Com_Image_4) | ||

| Finance | Obtain financial resources | The club seeks financial resources (Finance_1) | |

| Manage financial expenditure | The club manages its financial expenditure appropriately (Finance_2) | ||

| Manage self-financing capacity | The club manages its self-financing capacity (Finance_3) | ||

| Manage financial independence from the government | The club manages its financial independence from the government (Finance_4) | ||

| Organization | Improve the administrative and sports staff’s skills | The club improves its administrative and sports staff’s skills (Organization_1) | |

| Improve volunteer skills | The club improves volunteer skills (Organization_2) | ||

| Improve the headquarters’ internal functioning | The club improves its headquarters’ internal functioning (Organization_3) | ||

| Improve the headquarters’ organizational climate | The club improves its headquarters’ organizational climate (Organization_4) |

References

- Winand, M.; Scheerder, J.; Vos, S.; Zintz, T.; Hoeber, L. Service Innovation in Non-Profit Sport Organizations; European Academy of Management: Tallinn, Estonia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Winand, M.; Anagnostopoulos, C. Get ready to innovate! Staff’s disposition to implement service innovation in non-profit sport organisations. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2017, 9, 579–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerawardena, J.; Mort, G. Competitive strategy in socially entrepreneurial nonprofit organizations: Innovation and differentiation. J. Public Policy Mark. 2012, 31, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wemmer, F.; Koenigstorfer, J. Open Innovation in Nonprofit Sports Clubs. Voluntas 2016, 27, 1923–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winand, M.; Hoeber, L. Innovation Capability of Non-Profit Sport Organisations, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.M.; Olson, D.L.; Trimi, S. Co-innovation: Convergenomics, collaboration, and co-creation for organizational values. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 817–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priem, R.L. A Consumer Perspective on Value Creation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanovska, L.; Doubravsky, K. Does Provision of Smart Services Depend on Cooperation Flexibility, Innovation Flexibility, Innovation Performance or Business Performance in SMEs? Period. Polytech. Soc. Manag. Sci. 2021, 29, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, S.; Kase, K.; Urrutia, I. Value Creation and Sport Management. In Value Creation and Sport Management; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Minin, A.; Frattini, F.; Bianchi, M.; Bortoluzzi, G.; Piccaluga, A. Udinese Calcio soccer club as a talents factory: Strategic agility, diverging objectives, and resource constraints. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, P.; Peck, S.I.; Sasson, A. Competing Business Models, Value Creation and Appropriation in English Football. Long Range Plann. 2013, 46, 475–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V.; da Silva Braga, V.L.; da Encarnação Marques, C.S. Sport entrepreneurship and value co-creation in times of crisis: The covid-19 pandemic. J. Bus Res. 2021, 133, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, L.; Ryzhkova, N. Managing a strategic source of innovation: Online users. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2013, 33, 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugshan, H. Co-innovation: The role of online communities. J. Strateg. Mark. 2015, 23, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, T.; Slack, T.; Parent, M.M. Change. In Key Concepts in Sport Management; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2012; pp. 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannessen, J.-A.; Olsen, B. The future of value creation and innovations: Aspects of a theory of value creation and innovation in a global knowledge economy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2010, 30, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, L. Openness to Co-Creation of Value through the Lens of Generational Theory; Claremont Graduate University: Claremont, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hedlund, D. Creating value through membership and participation in sport fan consumption communities. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2014, 14, 50–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woratschek, H.; Durchholz, C.; Maier, C.; Ströbel, T. Innovations in sport management: The role of motivations and value cocreation at public viewing events. Event Manag. 2017, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolyperas, D.; Sparks, L. Exploring value co-creation in Fan Fests: The role of fans. J. Strateg. Mark. 2018, 26, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa, R.A.; N., R.; Gaviria; Guzmán, K. Estado de desarrollo de las organizaciones deportivas en Colombia. In Medellín, Colombia: Facultad de Cienicas Económicas e Instituto Universitario de Educación física; Universidad de Antioquia: Medellin, Colombia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Callejas, R.J.M.; Sierra, R.A.; García, N.G.; Zuluaga, C.R.; Giraldo, L. Approaches to the Study of Sports Associations: The Case of Clubs and Leagues in Antioquia-Colombia. 2013. MPRA Paper (Munich, Germany). Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/53174/1/MPRA_paper_53174.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- O’Boyle, I. The Identification and Management of Fundamental Performance Dimensions in National Level Non-Profit Sport Management; MPRA Paper: Munich, Germany; Belfast, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- O’Boyle, I.; Hassan, D. Performance management and measurement in national-level non-profit sport organisations. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2014, 14, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M. Creativity in Context Update to the Social Psychology of Creativity; Routledge: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Grönroos, C. Value co-creation in service logic: A critical analysis. Mark. Theory 2011, 11, 279–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, V. Co-creating experiences with customers: New paradigm of value creation. TMTC J. Manag. 2005, 8, 6–14. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C.; Byon, K.; Hung, H. Service Quality, Perceived Value, and Fan Engagement: Case Of Shanghai Formula One Racing. SMQ 2019, 28, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Na, S. Fear of Missing out: An Antecedent Of Online Fan Engagement of sport Teams’ Social Media. Commun. Amp Sport 2023, 14, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Byon, K. Central Actors In the Live Sport Event Context: A Sport Spectator Value Perception Model. SBM 2020, 10, 58–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byon, K.; Zhang, J.; Jang, W. Examining the Value Co-creation Model in Motor Racing Events: Moderating Effect of Residents And Tourists. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig-Lewis, N.; Asaad, Y.; Palmer, A. Sports Events and Interaction Among Spectators: Examining Antecedents of Spectators’ Value Creation. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2017, 18, 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woratschek, H.; Horbel, C.; Popp, B. Value co-creation in sport management. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2014, 14, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woratschek, H.; Horbel, C.; Popp, B. The sport value framework—A new fundamental logic for analyses in sport management. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2014, 14, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbel, C.; Popp, B.; Woratschek, H.; Wilson, B. How context shapes value co-creation: Spectator experience of sport events. Serv. Ind. J. 2016, 36, 510–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.P.; Soh, K.L.; Chong, C.L.; Karia, N. Logistics firms performance: Efficiency and effectiveness perspectives. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2015, 64, 686–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perck, J.; Hoecke, J.; Westerbeek, H.; Breesch, D. Organisational change in local sport clubs: The case of Flemish gymnastics clubs. Sport Bus. Manag. Int. J. 2016, 6, 158–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winand, M.; Vos, S.; Zintz, T.; Scheerder, J. Determinants of service innovation: A typology of sports federations. Int. J. Sport Manag. Mark. 2013, 13, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winand, M.; Qualizza, D.; Vos, S.; Scheerder, J.; Zintz, T. Fédérations sportives innovantes: Attitude, perceptions et champions de l’innovation. RIMHE Rev. Interdiscip. Manag. Homme(S) Entrep. 2013, 6, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, L.; Chelladurai, P.; Bodet, G.; Downward, P. Routledge Handbook of Sport Management, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Antony, J.P.; Bhattacharyya, S. Measuring organizational performance and organizational excellence of SMEs–Part 1: A conceptual framework. Meas. Bus. Excell. 2010, 14, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayle, E.; Madella, A. Development of a taxonomy of performance for national sport organizations. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2010, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowy, T.; Wicker, P.; Feiler, S.; Breuer, C. Organizational performance of nonprofit and for-profit sport organizations. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2015, 15, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winand, M.; Rihoux, B.; Qualizza, D.; Zintz, T. Combinations of key determinants of performance in sport governing bodies. Sport Bus. Manag. Int. J. 2011, 1, 234–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winand, M.; Scheerder, J.; Vos, S.; Zintz, T. Do non-profit sport organisations innovate? Types and preferences of service innovation within regional sport federations. Innov. Organ. Manag. 2016, 18, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Thrassou, A.; Vrontis, D. Football performance and strategic choices in Italy and beyond. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2013, 21, 546–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarijärvi, H.; Kannan, P.; Kuusela, H. Value co-creation: Theoretical approaches and practical implications. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2013, 25, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solakis, K.; Pena-Vinces, J.; Lopez-Bonilla, J.M. Value co-creation and perceived value: A customer perspective in the hospitality context. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2022, 28, 100175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Straub, D.W. A critical look at the use of PLS-SEM in MIS quarterly. MIS Q. 2012, 36, iii–xiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Zott, C. Value creation in E-business. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 493–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.; Lusch, R. Evolving to a New Dominant Logic for Marketing. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N. A Primer for Soft Modeling; University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Slack, T.; Parent, M.M. Understanding Sport Organizations: The Application of Organization Theory; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.W.; Christensen, C.M.; Kagermann, H. Reinventing Your Business Model. Harv. Bus Rev. 2008. Available online: https://hbr.org/2008/12/reinventing-your-business-model (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- Afuah, A. Business Model Innovation: Concepts, Analysis, and Cases; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, W.H. The wisdom of collaborative network organizations: Capturing the value of networked individuals. Prometheus 2008, 26, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimbürger, M.; Dietrich, P. Identifying the basis of collaboration performance in facility service business. Facilities 2012, 30, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K.; Lee, O.F.; Uslay, C. Mind the gap: The mediating role of mindful marketing between market and quality orientations, their interaction, and consequences. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2012, 29, 607–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The Partial Least Squares Approach for Structural Equation Modeling. In Modern Methods for Business Research with G; Marcoulides, A., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; SAGE Publishing: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Winand, M.; Zintz, T.; Bayle, E.; Robinson, L. Organizational performance of Olympic sport governing bodies: Dealing with measurement and priorities. Manag. Leis. 2010, 15, 279–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauss, T. Measuring Business Model Innovation: Conceptualization, Scale Development, and Proof of Performance. R&D Manag. 2016, 47, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winand, M.; Vos, S.; Claessens, M.; Thibaut, E.; Scheerder, J. A unified model of non-profit sport organizations performance: Perspectives from the literature. Manag. Leis. 2014, 19, 121–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisby, W. The organizational structure and effectiveness of voluntary organization: The case of Canadian sport governing bodies. J. Park Recreat. Admi. 1986, 3, 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Madella, A.; Bayle, E.; Tome, J. The organizational performance of national swimming federations in Mediterranean countries: A comparative approach. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2005, 5, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh, S.K.; Jayaraman, K.; Ismail, I.; Rahman, S.A. Scale development and validation for DART model of value co-creation process on innovation strategy. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2016, 31, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eime, R.M.; Payne, W.R.; Harvey, J.T. Making sporting clubs healthy and welcoming environments: A strategy to increase participation. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 2008, 11, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepak, D.P.; Smith, K.G.; Taylor, M.S. Value Creation and Value Capture: A Multilevel Perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 180–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corte, V.; Gaudio, G. A literature review on value creation and value capturing in strategic management studies. Corp. Ownersh. Control. 2014, 11, 328–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C. The relationship marketing process: Communication, interaction, dialogue, value. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2004, 19, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creating unique value with customers. Strategy Leadersh. 2004, 32, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | Percentage (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 288 | 94 |

| Female | 17 | 6 | |

| Education | Undergraduate degree | 153 | 50 |

| High School | 111 | 36 | |

| Postgraduate degree | 41 | 14 | |

| Position | Middle manager | 126 | 40 |

| Senior manager | 97 | 31 | |

| Coordinator | 82 | 29 |

| Dimensions | Items | Loadings * | CA | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sport | Sport_1 | 0.767 *** | 0.880 | 0.918 | 0.737 |

| Sport_2 | 0.912 *** | ||||

| Sport_3 | 0.894 *** | ||||

| Sport_4 | 0.852 *** | ||||

| Customers/members | Customer_M_1 | 0.824 *** | 0.828 | 0.886 | 0.661 |

| Customer_M_2 | 0.736 *** | ||||

| Customer_M_3 | 0.838 *** | ||||

| Customer_M_4 | 0.849 *** | ||||

| Communication and image | Com_Image_1 | 0.800 *** | 0.885 | 0.921 | 0.744 |

| Com_Image_2 | 0.867 *** | ||||

| Com_Image_3 | 0.911 *** | ||||

| Com_Image_4 | 0.868*** | ||||

| Finance | Finance_1 | 0.761 *** | 0.855 | 0.902 | 0.699 |

| Finance_2 | 0.887 *** | ||||

| Finance_3 | 0.869 *** | ||||

| Finance_4 | 0.820 *** | ||||

| Organization | Organization_1 | 0.883 *** | 0.909 | 0.936 | 0.786 |

| Organization_2 | 0.890 *** | ||||

| Organization_3 | 0.910 *** | ||||

| Organization_4 | 0.863 *** |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communication and image (1) | 0.863 | 0.946 | 0.773 | 0.802 | 0.884 |

| Customers/Members (2) | 0.813 | 0.813 | 0.808 | 0.818 | 0.924 |

| Finance (3) | 0.679 | 0.680 | 0.836 | 0.797 | 0.753 |

| Organization (4) | 0.720 | 0.709 | 0.705 | 0.887 | 0.792 |

| Sport (5) | 0.787 | 0.796 | 0.662 | 0.716 | 0.858 |

| Second-Order Construct | Dimensions | Collinearity Statistics | Weight-Load | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOL | VIF | Sig. Weight * | ||

| Value cocreation | Dialogue | 0.80 | 1.247 | Yes |

| Access | 0.82 | 1.205 | Yes | |

| Risk | 0.76 | 1.300 | Yes | |

| Transparency | 0.78 | 1.275 | Yes | |

| Value creation | New skills | 0.79 | 1.257 | Yes |

| New technology | 0.82 | 1.211 | Yes | |

| New partners | 0.82 | 1.216 | Yes | |

| New processes | 0.76 | 1.301 | Yes | |

| Structural Path | Path Coefficient | t-Value | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Value creation → Sport | 0.339 *** | 6.870 | H1a: Supported |

| Value creation → Customers/members | 0.340 *** | 6.867 | H1b: Supported |

| Value creation → Communication and image | 0.294 *** | 6.144 | H1c: Supported |

| Value creation → Finance | 0.278 *** | 6.978 | H1d: Supported |

| Value creation → Organization | 0.280 *** | 6.6693 | H1e: Supported |

| Value creation → Value cocreation | 0.575 *** | 15.260 | Supported |

| Value cocreation → Sport | 0.220 *** | 4.012 | Supported |

| Value cocreation → Customers/members | 0.250 *** | 5.546 | Supported |

| Value cocreation → Communication and image | 0.276 *** | 6.104 | Supported |

| Value cocreation → Finance | 0.281 *** | 6.674 | Supported |

| Value cocreation → Organization | 0.297 *** | 7.102 | Supported |

| Effect of | * Indirect Effect (t-Value) | Total Effect | VAF (%) | Interpretation | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VC → VCC → Sport | 0.127 *** (3.76) | 0.161 | 0.79 | Partial mediation | H2a: Supported |

| VC → VCC → Customer_M | 0.144 *** (5.25) | 0.171 | 0.84 | Full mediation | H2b: Supported |

| VC → VCC → Com_Image | 0.159 *** (5.66) | 0.187 | 0.85 | Full mediation | H2c: Supported |

| VC → VCC → Finance | 0.162 *** (5.89) | 0.189 | 0.85 | Full mediation | H2d: Supported |

| VC → VCC → Organization | 0.171 *** (6.02) | 0.199 | 0.86 | Full mediation | H2e: Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ortíz, J.I.B.; Henao, S.J.C.; Henao Colorado, L.C.; Valencia-Arias, A. Creating Value in Non-Profit Sports Organizations: An Analysis of the DART Model and Its Performance Implications. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 1676-1693. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe13090121

Ortíz JIB, Henao SJC, Henao Colorado LC, Valencia-Arias A. Creating Value in Non-Profit Sports Organizations: An Analysis of the DART Model and Its Performance Implications. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2023; 13(9):1676-1693. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe13090121

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrtíz, Jorge Iván Brand, Silvana Janeth Correa Henao, Laura Cristina Henao Colorado, and Alejandro Valencia-Arias. 2023. "Creating Value in Non-Profit Sports Organizations: An Analysis of the DART Model and Its Performance Implications" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 13, no. 9: 1676-1693. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe13090121

APA StyleOrtíz, J. I. B., Henao, S. J. C., Henao Colorado, L. C., & Valencia-Arias, A. (2023). Creating Value in Non-Profit Sports Organizations: An Analysis of the DART Model and Its Performance Implications. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 13(9), 1676-1693. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe13090121