Abstract

Limitations in some emotional characteristics that are conceptualized in the definition of emotional intelligence can be seen among people with autism spectrum disorder. The main objective of this study is the analysis of the effectiveness of interventions directed to enhance emotional recognition and emotional regulation among this specific population. A systematic review was carried out in databases such as Psycinfo, WoS, SCOPUS, and PubMed, identifying a total of 572 articles, of which 29 met the inclusion criteria. The total sample included 1061 participants, mainly children aged between 4 and 13 years. The analyzed interventions focused on improving emotional recognition, with significant results in the identification of emotions such as happiness, sadness, and anger, although some showed limitations in the duration of these effects. The most used programs included training in facial recognition, virtual reality, and the use of new technologies such as robots. These showed improvements in both emotional recognition and social skills. Other types of interventions such as music therapy or the use of drama techniques were also implemented. However, a gender bias and lack of consistency between results from different cultures were observed. The conclusions indicate that, although the interventions reviewed seem effective, more research is needed to maximize their impact on the ASD population.

1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2023), it is estimated that approximately one in one-hundred children worldwide has autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Over the past decades, an increase in the prevalence of ASD has been observed (Sevilla et al., 2013) and occurs in 1% of the global population (Zeidan et al., 2022). Therefore, studying ASD is crucial to ensuring an optimal quality of life for individuals and improving their personal development.

1.1. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

ASD is defined as a group of conditions characterized by difficulties in social interaction and communication (WHO, 2023). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR) describes autism as a neurodevelopmental disorder manifested by deficits in communication and social interaction, as well as restrictive and repetitive behavioral patterns (American Psychological Association (APA), 2022). The term autism was first coined by Kanner in 1943 and was applied to children with atypical socio-emotional development and significant socialization problems (Kanner, 1946). However, autism was not yet considered a specific diagnosis but rather a characteristic of childhood schizophrenia (Alcalá & Ochoa-Madrigal, 2022). It was not until the publication of the DSM-III-R (American Psychological Association, 1987) that it was named “Autistic Disorder.” Subsequent editions and modifications of the manual led to interpreting autism as a spectrum due to its etiology. To this day, the etiology remains unknown, and it is attributed to multifactorial reasons.

ASD symptoms are varied and usually manifest around 18 months, becoming more consolidated by 36 months of age (Reynoso et al., 2017). ASD is considered a spectrum, although there are common characteristics that form the basis for diagnosis. These characteristics are, for example, complex cognitive abilities developed from the first year of life, which are part of the theory of mind (ToM). People with ASD demonstrate a deficit in this capacity, which prevents them from attributing mental states to themselves and others (Hernández-Núñez, 2018). The ToM refers to the system humans use to infer mental states through behavior (Baron-Cohen et al., 1995). For instance, this includes the ability to predict others’ behavior, feelings, and intentions (Tirapu-Ustárroz et al., 2007). Considering that, their social relationships and development are significantly limited, hindering successful personal development.

ASD is often associated with other neurodevelopmental disorders (Lai et al., 2014). Historically, there has been an interest in studying the relationship between ASD and intelligence, often associating ASD with the intelligence quotient (IQ), as Binet and Simon did (Mora & Martín, 2007), or with a direct relationship with intellectual disability ([ID] López et al., 2009). As previously mentioned, ID is not a diagnostic determinant, although it may be comorbid. In fact, ID can occur in all variations of the spectrum except for Asperger’s syndrome or high-functioning ASD. Thus, considering the entire spectrum, two types of disorders can be identified: low-functioning ASD or ASD with ID and high-functioning ASD or Asperger’s syndrome (Vargas et al., 2019).

1.2. ASD and Emotional Intelligence (EI)

Emotional intelligence (EI) can be defined as encompassing all processes involved in recognizing, using, understanding, and managing emotional states, both one’s own and those of others (J. D. Mayer et al., 2008; Salovey & Mayer, 1990). Consequently, EI is understood as a set of multiple abilities, including the following: (a) emotional perception and expression, (b) emotional understanding, (c) emotional regulation (ER), and (d) the appropriate management and integration of emotions into reasoning. In fact, J. D. Mayer et al. (2000) developed a model of EI, stating that this construct comprises four components corresponding to distinct skills that influence our environment and social relationships. These skills include the following: (a) the ability to accurately perceive emotions, (b) the capacity to leverage emotional information to facilitate other cognitive processes, (c) the ability to understand emotions, and (d) the ability to regulate one’s own emotions as well as those of others. This model is known as the Ability Model.

There are other authors that defined EI. For example, Goleman’s (1995) mixed model is focused on interpersonal and intrapersonal intelligence. It emphasizes its link to the human capacity to recognize, control, and understand emotions, and self-motivate and manage social relationships (Hernández-Núñez, 2018). This framework aligns with the construct of EI defined by Salovey and Mayer in the 1990s (Kanesan & Fauzan, 2019). Another example is Gardner’s (1983) multiple intelligences theory, which described several modular intelligences that interact while also operating independently (Fernández, 2019; Sharma & Pandey, 2024). Goleman agreed with Gardner in rejecting the notion of rational intelligence as the sole predictor of success (Barrera-Gálvez et al., 2019). Finally, Bar-On’s (2006) Traits Model focuses on self-perception and emotional skills. However, the Ability Model can be considered highly suitable for the study of ASD due to its features (Kanesan & Fauzan, 2019). On the one hand, it is considered the most scientifically rigorous. On the other, its very definition emphasizes the cognitive processing of emotional information, which is highly related to ASD (Aguaded Gómez & Valencia, 2017; Anderson, 2015; S. S. Kuo et al., 2019).

1.3. The Current Study

As previously noted, individuals with ASD exhibit deficits in fundamental cognitive functions that are part of the ToM. They demonstrate difficulties in competencies such as emotional recognition ability (ERA) on the self or others, ER, and socio-communicative interaction in general (Hernández-Núñez, 2018). These competencies are directly linked to the construct of EI defined by Salovey and Mayer (1990). The emotional needs of these individuals are constrained due to deficits in these executive functions, which significantly affect their developmental trajectory. ERA, among other skills, is essential for understanding the mood of others (Beall et al., 2008). Therefore, it is imperative to intervene with ASD individuals to help them acquire these skills.

Multiple and different types of therapies have been implemented among people with ASD (Antshel & Russo, 2019; Genovese & Butler, 2020; Ona et al., 2020; Urinovsky & Cafiero, 2022). Indeed, current research indicates that certain interventions for ASD show promising results, particularly in improving ER, which can be valuable for enhancing EI (Guz et al., 2024; Omelchenko et al., 2024; Salimi et al., 2019; White et al., 2009).

This observation gives rise to the Patients/Problem, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcomes (PICO) question. P stands for people with ASD, I stands for interventions designed to enhance EI, C stands for comparing the intervention with a control group, and O stands for analyzing the effectiveness of their results. This leads to the formulation of the following Research Question (RQ): How effective are the interventions designed to enhance EI in people with ASD? From this inquiry emerges the primary aim of this study: to gather information on the most suitable interventions for developing EI in individuals with ASD. Also, the second objective is to explore the characteristics of these interventions, to see which are the most effective.

The interventions are analyzed based on the facets of EI described by J. D. Mayer et al. (2008): (1) emotion perception, (2) emotional understanding, (3) emotional management, and (4) the use of emotions to facilitate thought. By examining EI through its individual components, this review aims to achieve a deeper understanding of the specific needs of these individuals.

2. Materials and Methods

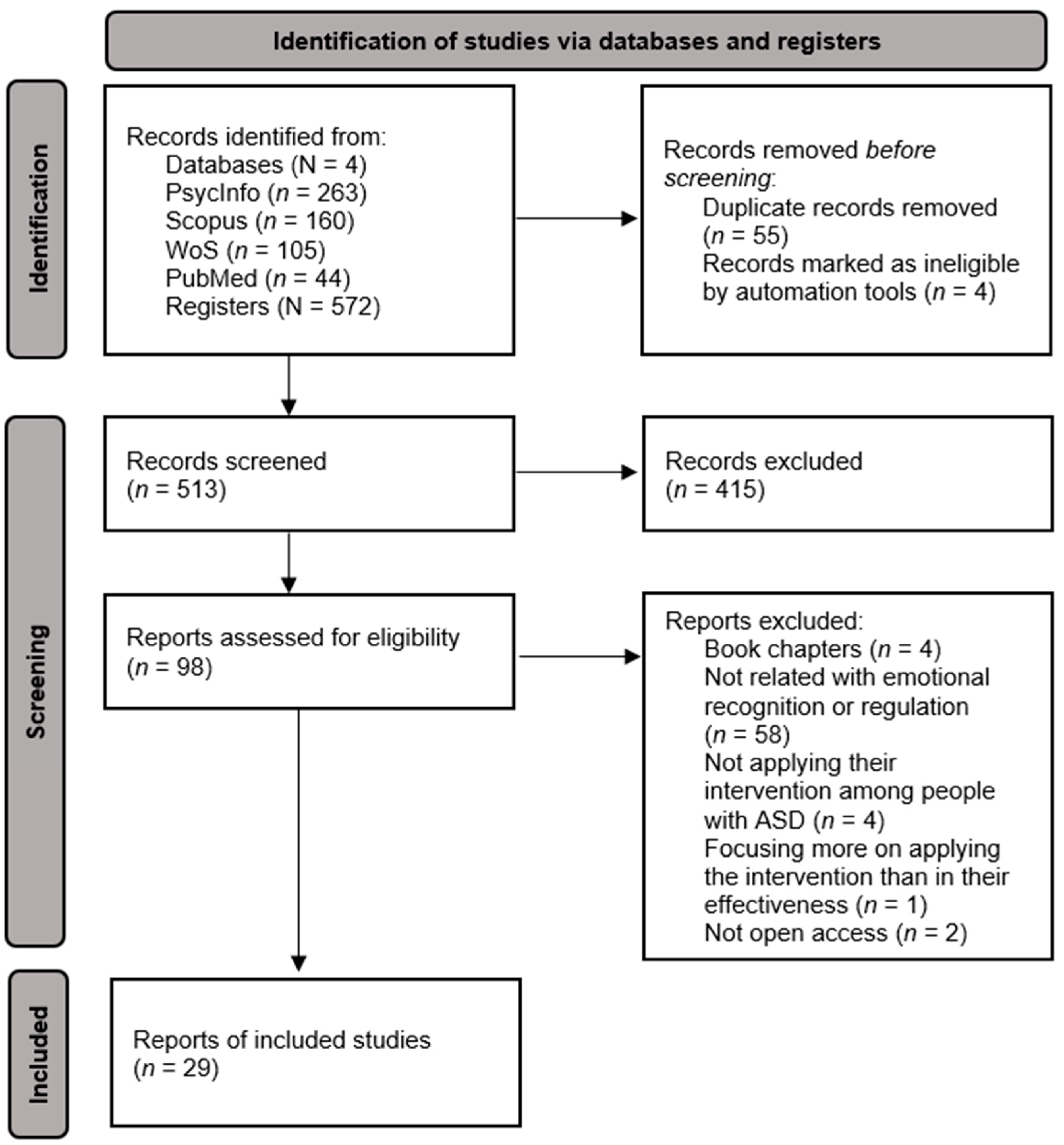

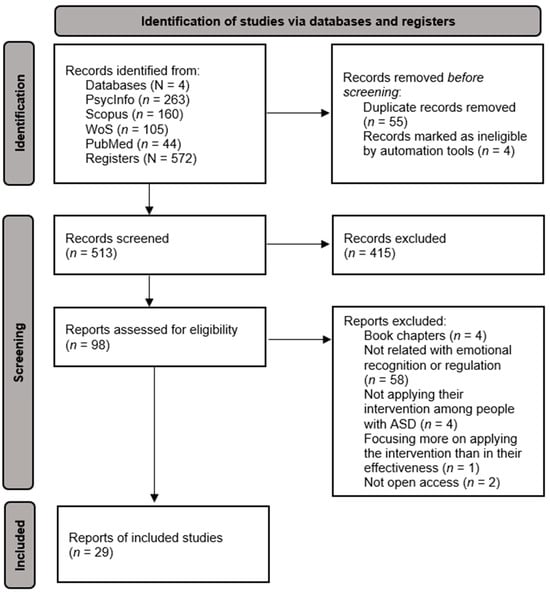

The PICO question components were taken into account when conducting the systematic review. Additionally, the preferred reported items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021) were applied to ensure the proper execution of the systematic review. The different phases of the procedure are detailed below (Appendix A). The international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) was used to preregister this process, with the identification number CRD42024587433.

2.1. Search Strategy and Sources of Information

A comprehensive analysis of available studies across various information sources was conducted to gather the most relevant evidence on the topic and adequately evaluate the established objectives. The systematic search was carried out between 10 April and 12 June 2024. The databases used included Psycinfo, Web of Science (WoS), SCOPUS, and PubMed, focusing on peer-reviewed scientific articles and excluding book chapters, dissertations, or editorials. The search terms used across all databases were as follows:

(Autis*) AND (“Emotional intelligence”) AND (Intervention).

The search was conducted on titles, abstracts, and keywords, without any time restrictions. It covered the period from 1980 to 2023, although no relevant records were found prior to 1984. It was considered not appropriate to include registers that were published after 2023, as the year 2024 was not finished when the review was completed. The term EI was used as a generic term to extend the results to the largest possible number of studies, leaving aside the components of its definition. However, the presence of these components was an essential criterium when the records identified from the databases were screened.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The selection process was based on the following criteria. Documents were included when they (a) were written in English or Spanish; (b) were empirical research articles, including both qualitative and quantitative scientific studies; (c) involved interventions related to the construct of EI, regarding the definition of J. D. Mayer et al. (2008), which covered all processes involved in recognizing, using, understanding, and managing emotional states, both one’s own and those of others; and (d) focused on individuals with ASD.

As exclusion criteria, the following were considered: (a) studies published after 31 December 2023; (b) book chapters, manuals, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, dissertations, editorials, or observational studies; (c) interventions not focused on ERA, regulation, or understanding; (d) interventions applied to parents or caregivers of individuals with ASD; (e) reports that focused mainly on the development of ER, rather than on their effectiveness; and (f) research which was not published in an open-access format and which could not be found by other means.

2.3. Codification and Critical Appraisal

These articles were analyzed in two stages: first, by reviewing only the title and abstract, and second, by reading the full text. During the review process, the Covidence platform was used to help with the management and organization of the literature review process by warranting the suitability of the studies. This tool ensured greater rigor and objectivity in the selection of studies, as each article was independently evaluated through an inter-rater examination. The following sections were extracted from each of the articles that were included in the systematic review. First, the authorship, year, and country of publication were extracted. Secondly, the main objective of studies with aspects related to EI was extracted. Third, regarding methodology aspects, the sample size, its division by sex, the number of participants with ASD, the presence of a control group, the type of intervention, its duration, and the evaluation instruments used were extracted. The reliability of the assessment tools was also reported when this was included in the original studies. Also, possible comorbidities between ASD and other disorders presented in the studies’ samples were reported, but only when the researchers explicitly indicated this in the body of the text. Finally, the results related to the objective of the present study were extracted.

To assess the quality of the selected studies, the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) system was used. This framework determines the level of scientific evidence and the strength of recommendations for each study.

3. Results

3.1. Selection of Studies

As a result, 263 articles were identified in Psycinfo, 105 in WoS, 160 in Scopus, and 44 in PubMed, with 572 articles in total. This number decreased to 513 after removing the articles that were duplicated. After the initial screening, during which the abstracts of all articles were reviewed, only 98 articles were selected. Of them, 69 were excluded after reading the body of their texts entirely, due to the following reasons: the intervention was not related to ER or recognition (n = 58), the intervention was applied to parents and caregivers rather than individuals with ASD (n = 4), the document was a book chapter rather than a scientific study (n = 4), the article focused more on the development of the intervention rather than its effectiveness and outcomes (n = 1), and obtaining access to the articles was not possible (n = 2). A total of 29 articles met the criteria to be included in the review (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram following PRISMA guidelines.

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the final studies included in the review, as well as a synthesis of their results, organized chronologically by the year of publication.

Table 1.

Information from the selected articles.

3.2. Synthesis of Results

3.2.1. Demographic Characteristics

The analyzed studies were mostly conducted in the United States (n = 8) and Asia (four in China, two in Japan, two in Israel, one in Taiwan, and one in South Korea). In total, they covered 62.07% of the articles included in the review. On the other hand, in Europe, studies have been carried out in different countries such as Italy (n = 2), Macedonia (n = 1), Spain (n = 1), Sweden (n = 1), and the United Kingdom (n = 1), representing 20.69% of the total. Additionally, one study was conducted in Morocco and six were conducted in Australia (20.69%).

The sample population is composed of 1,061 children, adolescents, and young adults. Participants between 4 and 13 years of age were considered children, participants between 14 and 18 were considered adolescents, and participants over 18 years of age were considered adults or young adults. The studies focused mainly on children (twenty-one articles), while only three articles focused on adults. On the other hand, five articles focused on populations that include children, adolescents, and adults. Therefore, there were 688 participants aged between 4 and 13 years old, representing 64.36% of the sample population; there were 50 participants aged between 14 and 18 years old, representing 4.68%; and 35.73% (382 participants) were aged 18 years old or older.

Most studies used male populations. The total sample was composed of 706 men participants, compared to 99 women. Still, it is noteworthy that several studies do not provide information on the gender of the participants. It should also be highlighted that the only study where the proportion of women exceeded that of men was the one from Lee et al. (2018), which focused on emotional skills.

Finally, according to the possible comorbidities associated with the diagnosis of ASD, 15 articles did not report this in the body of their text. Other studies (n = 8) specifically reported excluding people from their samples when they presented with other disorders in addition to ASD (Chen et al., 2014; Frolli et al., 2022; Kandalaft et al., 2013; Kuroda et al., 2022; Lecciso et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2018; Petrovska & Trajkovski, 2019; Ramirez-Melendez et al., 2022). Some of the studies included samples in which participants presented with other disorders. For instance, Shaffer et al. (2022) and Beaumont et al. (2015) indicated the specific diagnoses that were contemplated. In these cases, there were participants with ADHD, anxiety and depressive disorders, oppositional defiant disorders, obsessive compulsive disorders, etc. Other articles stated that their sample included other conditions, but did not explicitly label them. For example, Elhaddadi et al. (2021) included people that could not talk or read, Tse (2020) included people with emotional and behavioral problems, and Matsuda and Yamamoto (2014) said that their sample was composed of people with a lower mental age than their current age. Also, Kandalaft et al. (2013) pointed out that the presentation of depression, which was being managed, was not an exclusion criterium for them, even when they also indicated that presenting with other disorders was not allowed.

3.2.2. Results Regarding Type and Duration of Interventions

Regarding the objectives in each study, all of them are linked with, at least, one of the facets of EI. These include recognition, understanding, management, and the use of emotions (J. D. Mayer et al., 2008). As can be seen in Table 1, eighteen studies focused mainly on ERA (62.07%) and seven focused on social skills (24.14%). Table 1 explicitly shows how the objectives are linked to the methodology used to achieve them, and also the results that arise from them. In terms of effectiveness, most have shown significant improvements in both ERA and ER, as well as in social skills. According to Elhaddadi et al. (2021), the most frequently improved emotions were happiness, anger, sadness, and surprise. On the other hand, some interventions, such as the use of the DVD “The Transporters” by Williams et al. (2012), showed limited and unsubstantiated improvements. Even so, most interventions proved effective and demonstrated a potential increase in ERA in individuals with ASD.

According to training programs, seven studies used facial recognition (Gev et al., 2016; Rice et al., 2015; Russo-Ponsaran et al., 2015; Lacava et al., 2010; Williams et al., 2012; Yan et al., 2018; Young & Posselt, 2012). Of these seven, four articles worked with the same program, which used the DVD “The Transporters”. The results were highly varied, which may be due to the different countries where it was applied. In Australia, the effectiveness of this program was limited, as it increased ERA skills but did not sustain them over time (Williams et al., 2012; Young & Posselt, 2012). On the other hand, in Israel, the results showed an increase in recognition skills, which was sustained for three months, although no differences were observed in emotional vocabulary (Gev et al., 2016). Finally, in China, the program was effective for both recognition skills and emotional vocabulary (Yan et al., 2018). The other three remaining articles demonstrated positive results, which generalized to other contexts. All three articles highlighted an increase in ERA skills, particularly for primary emotions such as sadness, happiness, anger, disgust, and fear. Indeed, the article by Russo-Ponsaran et al. (2015) also highlighted improvements in emotional expression, particularly anger, disgust, and surprise.

Other articles (n = 3) used virtual reality (VR) or augmented reality to intervene with ASD subjects (Chen et al., 2014; Frolli et al., 2022; Kandalaft et al., 2013). The results obtained by these interventions were positive. After application, subjects could better recognize emotions, both facially and vocally. Moreover, after the treatment, they expressed their feelings more frequently. Notably, both the control group and the experimental group (Frolli et al., 2022) increased ERA, but the group with the VR intervention was able to recognize emotions much faster.

Some of the studies (n = 4) employed different programs related to social skills and ERA (Beaumont & Sofronoff, 2008; Beaumont et al., 2015; Petrovska & Trajkovski, 2019; Shaffer et al., 2022). Their results showed an increase in ER, the development of social skills, and better recognition and emotional understanding. These results were also reported by the parents and teachers of the subjects undergoing the intervention. Also, music therapy was used in two articles to intervene with ASD (Huang, 2023; Ramirez-Melendez et al., 2022). Their results indicated better emotional interpretation through music and a reduction in emotional dysregulation.

Games were used on three occasions (Doernberg et al., 2021; Elhaddadi et al., 2021; Fridenson-Hayo et al., 2017). Their results demonstrated gains in ERA, as well as a greater accuracy and understanding of emotions such as happiness, anger, sadness, and fear. The use of robots was present in two articles. One used robots as facilitators for the intervention and compared them to the use of people (Yun et al., 2017). The results showed no significant differences, with both groups achieving improved ERA. The second article compared the use of robots with computers (Lecciso et al., 2021). The two technologies achieved positive results, increasing both ERA and the expression of basic emotions.

Socio-emotional skills training was employed in three articles. The results of one of them indicate that people with ASD in school settings increased emotional competencies. However, these outcomes were not generalizable to other contexts (Ratcliffe et al., 2014). On the other hand, the results of the others showed an increase in these socio-emotional skills, particularly in recognizing four emotions: surprise, happiness, anger, and sadness (Lee et al., 2018; Matsuda & Yamamoto, 2014).

The remaining articles (17.24%) employed various other interventions. Guastella et al. (2010) used oxytocin, obtaining beneficial results in ERA. Physical exercise was used in Tse (2020) and achieved a significant improvement in emotional expression in ASD subjects. Another intervention used theater (Corbett et al., 2010), where the authors obtained significant results in the facial identification of emotions. Limited benefits on ER were observed when using cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and were not maintained over time (Kuroda et al., 2022). Lastly, Stichter et al. (2010) used social competence, obtaining a clear improvement in ERA.

Regarding the duration of interventions, the average duration was eight and a half weeks. The socio-emotional skills training by Ratcliffe et al. (2014) was the longest, lasting six months. The intervention with matching-to-sample tasks by Matsuda and Yamamoto (2014) was the shortest, lasting approximately one week. However, there were also single-session interventions, such as in the case of Lacava et al. (2010), where the MindReading program was used.

3.2.3. Assessment Tools

The instruments used for the assessment varied depending on what the studies aimed to measure. The most repeated measures were the following. The first was the Autism Diagnostic Observational Schedule ([ADOS-2]; C. Lord et al., 2015), which appears in multiple studies and is the most used tool to assess the primary symptoms for diagnosing ASD. The second was the Autism Diagnostic Interview—Revised ([ADI-R]; C. Lord et al., 1994), which is a clinical interview that helps clarify suspicions of ASD. Also, the Wechsler Intelligence Scale ([WISC]; Wechsler, 2011) was used, which appears repeatedly across different articles in its various versions (WISC-IV or WISC-V) and is used to measure intelligence. Furthermore, other scales were used to assess the variables that are different from ASD and intelligence. For instance, the following scales were used: the Social Communication Questionnaire ([SCQ]; Bölte et al., 2008), which evaluates social communication, the Social Responsiveness Scale ([SRS]; Beule & Karlovsky, 2020), which measures symptom rigidity, the Infant Neuropsychological Battery ([NEPSY-II]; Korkman et al., 2007), which measures neuropsychological functioning, and the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales ([VABS]; Sparrow & Cicchetti, 1989), which assess adaptive behavioral skills.

3.3. Quality Assessment Results

Considering the quality of the articles included, 24 of the analyzed studies (82.76%) showed consistency in high-quality evidence. Meanwhile, five studies exhibited moderate-quality evidence. However, their recommendation remains strong (see Table 2). Within the context of the GRADE system, this indicates that the benefits of the intervention clearly outweigh its risks and costs, highlighting general applicability, confidence in its implementation, and sufficiently clear results to justify this recommendation. These findings suggest that most individuals within the specific scope of the articles analyzed are likely to achieve similar outcomes.

Table 2.

GRADE Scale results.

4. Discussion

The RQ in this study was as follows: How effective are the interventions designed to enhance EI in people with ASD? Therefore, the primary purpose of this study is to contribute to the field of research by providing information about the most effective interventions to enhance the emotional competencies of individuals with ASD. To achieve this, an analysis of the existing scientific literature on EI and ASD was conducted through a search of all articles published between 1980 and 2024. The review of the data analyzed provides a detailed view of the effectiveness of these interventions, highlighting different outcomes.

One of the most positive aspects of the results is the cultural diversity presented in the analyzed studies. This wide representation of countries and cultures contributes to the diversity of the sample. The research spans different countries across four continents: Europe, America, Africa, and Oceania. This wide geographic representation allows for a more global understanding of the interventions and suggests that ASD is not an issue confined to certain countries or cultures but is a disorder with worldwide prevalence (Málaga et al., 2019; WHO, 2023). This finding aligns with previous studies that have also identified ASD as a global phenomenon with relatively similar prevalence across various cultures, reinforcing the idea that the disorder is determined by neurobiological factors rather than exclusively by cultural and socioeconomic conditions (Elsabbagh et al., 2012). Nevertheless, it is worth considering whether these interventions that have proven effective in other countries might be culturally adapted. The literature suggests that culture influences social interactions (Davenport et al., 2018; Golson et al., 2022), which could imply that interventions effective in one context may not be equally effective in another. For instance, in the case of the program “The Transporters”, which has been used in countries like Israel, Australia, and China, the results vary significantly among them. This fact suggests that the way in which certain executive functions, such as ERA, are taught and internalized may be influenced by cultural factors. Therefore, to maximize their effectiveness, it may be necessary to adapt interventions to different cultural contexts.

Another noteworthy aspect is the predominance of children in the sample, as 72.41% of the studies focus on this population. This is understandable, since the diagnosis of ASD is usually made at early ages (Loubersac et al., 2023; Rojas et al., 2019) and early interventions have been shown to be more effective in improving the development of social and emotional skills (Wergeland et al., 2022). Moreover, this is very important as it enables children with ASD to reach their maximum potential and improve their quality of life (Rojas et al., 2019). However, this focus on childhood may limit the application of the results to other life stages, such as adolescence or adulthood, since only 10.43% of the studies include this sample.

A critical aspect is the gender disparity in the samples, as the majority of participants are male (66.54% compared to 9.33%). This shows that the sample is quite unbalanced in terms of gender. This bias may be due to the prevalence of ASD, which is four times higher in males than in females (Montagut et al., 2018). However, recent studies suggest that ASD in females may be underdiagnosed due to differences in symptom presentation, particularly in the social domain, as females tend to mask symptoms to fit in socially (Ferri et al., 2018). This highlights the importance of including more females in future research, as this imbalance in the sample limits the ability to generalize the findings to females with ASD.

Additionally, according to ASD’s comorbidities, only two out of the twenty-nine studies selected explicitly reported them (Beaumont et al., 2015; Shaffer et al., 2022). Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have shown that ASD usually presents with comorbid disorders, with ADHD, anxiety, and depression disorders being the most repeated (Bougeard et al., 2024; Micai et al., 2023). Functional neurological disorders have also been considered to be related to ASD lately (Vickers et al., 2024). The lack of the evaluation of samples regarding these disorders is clearly a gap in their studies, which might be addressed in future research.

As previously mentioned, ERA and social skills are the areas most addressed in the analyzed studies. This aligns with the original facets of the definition of EI (J. D. Mayer et al., 2008). Most interventions have proven effective in improving these skills, which is consistent with previous studies indicating that deficits in ERA are a core feature of ASD (Dollion et al., 2022; Harms et al., 2010). Nevertheless, some interventions have not been effective, such as CBT, used in the study by Kuroda et al. (2022), and the “The Transporters” DVD, when used in the study of Williams et al. (2012). The emotions most frequently improved by the interventions include happiness, anger, sadness, and fear, which align with the so-called primary or universal emotions (Cowen et al., 2019). This trend is consistent with previous studies suggesting that basic emotions are more easily recognizable than more complex emotions, such as shame, as they involve a greater understanding of social norms (Ekman, 1999).

One of the most interesting conclusions is that interventions using new technologies such as VR, robots, and computer programs tend to be more effective, achieving faster ERA compared to more traditional interventions such as theater or music therapy. This may be because new technologies allow for greater adaptability and personalization of interventions, offering the possibility of creating controlled environments where subjects can repeatedly practice without the pressure of real social interaction (Lahiri et al., 2014). This aligns with the results of a recent systematic review that addresses the use of technology-based interventions in people with ASD, which, among other things, states that they can be useful for increasing their ER (Sumra & Sumra, 2024). However, although these interventions show promising results, traditional interventions should not be underestimated. Theater, for example, has been proven to be effective in improving emotional identification (Corbett et al., 2010). Also, music therapy has shown improvements in emotional interpretation as well as reductions in dysregulation, highlighting the importance of employing multisensory approaches in interventions (Ramirez-Melendez et al., 2022). Moreover, management interventions such as cognitive-behavioral therapies, physical activity, and stress and anger management programs have been indicated for enhancing ER (Sari et al., 2024). Therefore, while new technologies are a valuable tool, they should not entirely replace traditional approaches, but rather complement them to create a more holistic and effective approach (Yun et al., 2017).

Despite the positive results of most interventions, some have not been completely effective or have failed to maintain the achieved results over time. An example is the case of using the program “The Transporters” in Australia, which, although initially improving ERA, does not sustain these improvements over time (Williams et al., 2012). This underscores the importance of designing interventions that not only improve skills in the moment but also promote the consolidation of these improvements and the generalization of these skills to other contexts. Another study that failed to achieve fully effective results is the use of CBT by Kuroda et al. (2022), which, while improving ER in the short term, does not maintain these improvements after the intervention ends.

4.1. Limitations and Future Research

It is important to consider the limitations of the present study. First, there is a clear gender disparity in the samples, limiting the generalization of these results to females and girls with ASD, further reinforcing the idea that such disorders predominantly affect males (Calderoni, 2023). Second, some interventions have shown effectiveness only in the short term (e.g., the study by Kuroda et al., 2022), meaning the results of these interventions are not sustained after a period of application, suggesting that more long-term research is needed to assess the durability of effects. Also, regarding the duration of the interventions, differences between studies can be one of the determining factors in the effectiveness of interventions. Although this does not seem to be the only factor, prolonged treatment may offer more time for practicing and consolidating emotional skills.

Another critical aspect is the sample size, as it was quite limited in some studies, being shorter than five participants in a few cases (Chen et al., 2014; Huang, 2023; Lacava et al., 2010; Matsuda & Yamamoto, 2014). This may reduce the ability to generalize findings to the broader ASD population, especially given the wide range of symptomatology and manifestations within the spectrum (S. S. Kuo et al., 2022). Additionally, including studies that explicitly report comorbid disorders among their sample is fundamental, as they are not only common, but could also be sensitive to gender and age (Bougeard et al., 2024). Additionally, although some of the instruments used in the studies are widely known, such as the WISC (Wechsler, 2011), 62.10% of the analyzed studies, or a total of 18 articles, do not report reliability and validity information for their instruments. This lack of information can compromise the robustness of the results obtained. This is particularly relevant for studies using less common measurement tools or those not validated in different populations, as it limits their replicability. Using PRISMA-COSMIN guidelines would be considered interesting for the future if researchers are willing to specifically analyze the psychometric proprieties of the measurement instruments that have been used for this topic (Elsman et al., 2024). However, this is not the case of the present study. The objective of this study fits the definition of PRISMA guidelines better, which are recommended to be used when analyzing the effects of health interventions (Page et al., 2021). Finally, as it happens in systematic reviews and meta-analyses, publication biases must be considered (Nair, 2019). This means it is probable that only the statistically significant results were published, and consequently, taken into account in this review.

4.2. Practical Implications

Regarding the practical applications derived from this study, the results suggest that programs based on ERA, VR, or music therapy can be implemented in educational and therapeutic settings to improve the socio-emotional skills of individuals with ASD. An example of this is the case of socio-emotional skills training by Ratcliffe et al. (2014). Although the results do not generalize to other contexts in addition to the classroom, the results showed an improvement in the skills of individuals with ASD. These interventions offer effective tools to promote the social well-being of this population, enabling mental health and education professionals to adapt these strategies to the specific needs of individuals, thereby personalizing approaches and enhancing their effectiveness. In general terms, the implementation of these interventions is beneficial both educationally and socially, as by working on EI, these interventions can promote social inclusion and facilitate the participation of individuals with ASD in everyday settings, thus contributing to their integration and more accessible development.

5. Conclusions

Based on the results, and answering the RQ, it can be stated that interventions conducted on individuals with ASD to address EI and achieve improvements in this area can be effective. The reviewed studies suggest that these interventions are particularly effective in the field of ERA. The use of new technologies such as VR or electronic devices such as robots or computers offers promising results, achieving improvements in various facets of EI in a shorter period. Traditional interventions have also proven effective and should not be dismissed.

Finally, it would be advisable to continue exploring new instruments and approaches to more precisely measure EI in this population to further enhance the effectiveness of interventions. Furthermore, future studies should address the generalization of long-term effects, include more women in samples, and explore other areas of EI, such as ER or the use of emotions to evoke thoughts more simply.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.G.-G. and M.M.-V.; methodology, S.H.-F. and J.C.-P.; software, L.G.-G. and M.M.-V.; validation, S.H.-F. and J.C.-P.; formal analysis, L.G.-G. and M.M.-V.; investigation, L.G.-G. and M.M.-V.; resources, M.M.-V.; data curation, L.G.-G. and M.M.-V.; writing—original draft preparation, L.G.-G. and M.M.-V.; writing—review and editing, J.C.-P.; visualization, S.H.-F.; supervision, M.M.-V.; project administration, M.M.-V.; funding acquisition, M.M.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| DSM | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders |

| APA | American Psychological Association |

| ToM | Theory of Mind |

| ID | Intellectual Disability |

| IQ | Intelligence Quotient |

| EI | Emotional Intelligence |

| ER | Emotional Regulation |

| ERA | Emotional Recognition Ability |

| PICO | Patients/Problem, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes |

| RQ | Research Question |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROSPERO | International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| WoS | Web of Science |

| GRADE | Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation |

| ADHD | Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder |

| VR | Virtual Reality |

Appendix A

Table A1.

PRISMA checklist indicating where to find each item.

Table A1.

PRISMA checklist indicating where to find each item.

| Item | Yes | No | Page | NA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TITLE | ||||

| 1. Title | X | 1 | ||

| ABSTRACT | ||||

| 2. Abstract | X | 1 | ||

| INTRODUCTION | ||||

| 3. Rationale | X | 1 | ||

| 4. Objectives | X | 2 | ||

| METHODS | ||||

| 5. Eligibility criteria | X | 3 | ||

| 6. Information sources | X | 2 | ||

| 7. Search strategy | X | 2 | ||

| 8. Selection process | X | 3 | ||

| 9. Data collection process | X | 3 | ||

| 10. Data items | X | 3 | ||

| 11. Bias assessment | X | 3 | ||

| 12. Effect measures | X | |||

| 13. Synthesis methods | X | |||

| 14. Reporting bias assessment | X | |||

| 15. Certainty assessment | X | |||

| RESULTS | ||||

| 16. Study selection | X | 4 | ||

| 17. Study characteristics | X | 4 | ||

| 18. Risk of bias | X | 19 | ||

| 19. Individual studies | X | 4 | ||

| 20. Synthesis | X | 17 | ||

| 21. Reporting biases | X | |||

| 22. Certainty of evidence | X | |||

| DISCUSSION | ||||

| 23. Discussion | X | 19 | ||

| OTHER | ||||

| 24. Registration | X | 2 | ||

| 25. Support | X | 23 | ||

| 26. Competing interests | X | 23 | ||

| 27. Available data | X | 23 |

Note. NA: Not applicable.

References

- Aguaded Gómez, M. C., & Valencia, J. (2017). Estrategias para potenciar la inteligencia emocional en educación infantil: Aplicación del modelo de Mayer y Salovey. Tendencias Pedagógicas, 30, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alcalá, G. C., & Ochoa-Madrigal, M. G. (2022). Trastorno del espectro autista (TEA). Revista de la Facultad de Medicina (México), 65(1), 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. (1987). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed., rev.). American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association (APA). (2022). Manual diagnóstico y estadístico de los trastornos mentales DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). Editorial Médica Panamericana. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, L. B. (2015). Emotional intelligence in agenesis of the corpus callosum: Results from the mayer-salovey-caruso emotional intelligence test. Fuller Theological Seminary, School of Psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Antshel, K. M., & Russo, N. (2019). Autism spectrum disorders and ADHD: Overlapping phenomenology, diagnostic issues, and treatment considerations. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-On, R. (2006). The bar-on model of emotional-social intelligence (ESI) 1. Psicothema, 18, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen, S., Campbell, R., Karmiloff-Smith, A., Grant, J., & Walker, J. (1995). Are children with autism blind to the mentalistic significance of the eyes? British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 13(4), 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Gálvez, R., Solano-Pérez, C. T., Arias-Rico, J., Jaramillo-Morales, O. A., & Jiménez-Sánchez, R. C. (2019). La inteligencia emocional en estudiantes universitarios. Educación Y Salud Boletín Científico Instituto De Ciencias De La Salud Universidad Autónoma Del Estado De Hidalgo, 7(14), 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beall, P. M., Moody, E. J., McIntosh, D. N., Hepburn, S. L., & Reed, C. L. (2008). Rapid facial reactions to emotional facial expressions in typically developing children and children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 101(3), 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, R., Rotolone, C., & Sofronoff, K. (2015). The secret agent society social skills program for children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders: A comparison of two school variants. Psychology in the Schools, 52(4), 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, R., & Sofronoff, K. (2008). A multi-component social skills intervention for children with Asperger syndrome: The junior detective training program. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(7), 743–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beule, L., & Karlovsky, P. (2020). Improved normalization of species count data in ecology by scaling with ranked subsampling (SRS): Application to microbial communities. PeerJ, 8, e9593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougeard, C., Picarel-Blanchot, F., Schmid, R., & Buitelaar, J. (2024). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder and co-morbidities in children and adolescents: A systematic literature review. Physical Review Focus, 22(2), 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bölte, S., Holtmann, M., & Poustka, F. (2008). The Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) as a screener for autism spectrum disorders: Additional evidence and cross-cultural validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(6), 719–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderoni, S. (2023). Sex/gender differences in children with autism spectrum disorder: A brief overview on epidemiology, symptom profile, and neuroanatomy. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 101(5), 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-H., Lee, I.-J., & Lin, L.-Y. (2014). Augmented reality-based self-facial modeling to promote the emotional expression and social skills of adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 36, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbett, B. A., Gunther, J. R., Comins, D., Price, J., Ryan, N., Simon, D., Schupp, C. W., & Rios, T. (2010). Brief report: Theatre as therapy for children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(4), 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowen, A. S., Elfenbein, H. A., Laukka, P., & Keltner, D. (2019). Mapping 24 emotions conveyed by brief human vocalization. American Psychologist, 74(6), 698–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davenport, M., Mazurek, M., Brown, A., & McCollom, E. (2018). A systematic review of cultural considerations and adaptation of social skills interventions for individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 52, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doernberg, E. A., Russ, S. W., & Dimitropoulos, A. (2021). Believing in make-believe: Efficacy of a pretend play intervention for school-aged children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(2), 576–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollion, N., Grandgeorge, M., Saint-Amour, D., Hosein Poitras Loewen, A., François, N., Fontaine, N. M. G., Champagne, N., & Plusquellec, P. (2022). Emotion facial processing in children with autism spectrum disorder: A pilot study of the impact of service dogs. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 869452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P. (1999). Basic emotions. In T. Dalgleish, & M. J. Power (Eds.), Handbook of cognition and emotion (pp. 45–60). John Wiley & Sons Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhaddadi, M., Maazouz, H., Alami, N., Drissi, M. M., Mènon, C. S., Latifi, M., & Ahami, A. O. T. (2021). Serious games to teach emotion recognition to children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Acta Neuropsychologica, 19(1), 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsabbagh, M., Divan, G., Koh, Y. J., Kim, Y. S., Kauchali, S., Marcín, C., Montiel-Nava, C., Patel, V., Paula, C. S., Wang, C., Yasamy, M. T., & Fombonne, E. (2012). Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism Research, 5(3), 160–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsman, E. B., Mokkink, L. B., Terwee, C. B., Beaton, D., Gagnier, J. J., Tricco, A. C., Baba, A., Butcher, N. J., Smith, M., Hofstetter, C., Aiyegbusi, O. L., Berardi, A., Farmer, J., Haywood, K. L., Krause, K. R., Markham, S., Mayo-Wilson, E., Mehdipour, A., Ricketts, J., … Offringa, M. (2024). Guideline for reporting systematic reviews of outcome measurement instruments (OMIs): PRISMA-COSMIN for OMIs 2024. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 173, 111422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M. T. (2019). Las inteligencias múltiples como modelo educativo del siglo XXI. Almoraima: Revista de Estudios Campogibraltareños, 50, 205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Ferri, S. L., Abel, T., & Brodkin, E. S. (2018). Sex differences in autism spectrum disorder: A review. Current Psychiatry Reports, 20, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridenson-Hayo, S., Berggren, S., Lassalle, A., Tal, S., Pigat, D., Meir-Goren, N., O’Reilly, H., Ben-Zur, S., Bölte, S., Baron-Cohen, S., & Golan, O. (2017). ‘Emotiplay’: A serious game for learning about emotions in children with autism: Results of a cross-cultural evaluation. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 26(8), 979–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolli, A., Savarese, G., di Carmine, F., Bosco, A., Saviano, E., Rega, A., Carotenuto, M., & Ricci, M. C. (2022). Children on the autism spectrum and the use of virtual reality for supporting social skills. Children, 9(2), 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Genovese, A., & Butler, M. G. (2020). Clinical assessment, genetics, and treatment approaches in autism spectrum disorder (ASD). International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(13), 4726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gev, T., Rosenan, R., & Golan, O. (2016). Unique effects of The Transporters animated series and of parental support on emotion recognition skills of children with ASD: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Autism Research, 10(5), 993–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goleman, D. (1995). Inteligencia emocional. Kairós Sa. [Google Scholar]

- Golson, M. E., Ficklin, E., Haverkamp, C. R., McClain, M. B., & Harris, B. (2022). Cultural differences in social communication and interaction: A gap in autism research. Autism Research, 15(2), 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guastella, A. J., Einfeld, S. L., Gray, K. M., Rinehart, N. J., Tonge, B. J., Lambert, T. J., & Hickie, I. B. (2010). Intranasal oxytocin improves emotion recognition for youth with autism spectrum disorders. Biological Psychiatry, 67(7), 692–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guz, E., Niderla, K., & Kata, G. (2024). Advancing autism therapy: Emotion analysis using rehabilitation robots and ai for children with ASD. Journal of Modern Science, 57, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, M. B., Martin, A., & Wallace, G. L. (2010). Facial emotion recognition in autism spectrum disorders: A review of behavioral and neuroimaging studies. Neuropsychology Review, 20, 290–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Núñez, A. (2018). Desarrollo de la inteligencia emocional en el alumnado con autismo. Revista de Investigación y Educación en Ciencias de la Salud (RIECS), 3(2), 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. (2023). Intervention of music therapy on emotional disorders of autistic children in the context of intelligent medical internet of things. Internet Technology Letters, 7(6), e457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandalaft, M. R., Didehbani, N., Krawczyk, D. C., Allen, T. T., & Chapman, S. B. (2013). Virtual reality social cognition training for young adults with high-functioning autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(1), 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanesan, P., & Fauzan, N. (2019). Models of emotional intelligence: A review. e-BANGI Journal, 16(7), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kanner, L. (1946). Irrelevant and metaphorical language in early infantile autism. American Journal of Psychiatry, 103(2), 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkman, M., Kirk, U., & Kemp, S. (2007). NEPSY—Second edition (NEPSY—II) (Database record). APA PsycTests. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, S. S., Van Der Merwe, C., Fu, J. M., Carey, C. E., Talkowski, M. E., Bishop, S. L., & Robinson, E. B. (2022). Developmental variability in autism across 17000 autistic individuals and 4000 siblings without an autism diagnosis. JAMA Pediatrics, 176(9), 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, S. S., Wojtalik, J. A., Mesholam-Gately, R. I., Keshavan, M. S., & Eack, S. M. (2019). Establishing a standard emotion processing battery for treatment evaluation in adults with autism spectrum disorder: Evidence supporting the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotion Intelligence Test (MSCEIT). Psychiatry Research-Neuroimaging, 278, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, M., Kawakubo, Y., Kamio, Y., Yamasue, H., Kono, T., Nonaka, M., Matsuda, N., Kataoka, M., Wakabayashi, A., Yokoyama, K., Kano, Y., & Kuwabara, H. (2022). Preliminary efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy on emotion regulation in adults with autism spectrum disorder: A pilot randomized waitlist-controlled study. PLoS ONE, 17(11), e0277398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacava, P. G., Rankin, A., Mahlios, E., Cook, K., & Simpson, R. L. (2010). A single case design evaluation of a software and tutor intervention addressing emotion recognition and social interaction in four boys with ASD. Autism, 14(3), 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahiri, U., Bekele, E., Dohrmann, E., Warren, Z., & Sarkar, N. (2014). Physiologically informed virtual reality based social communication system for individuals with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45, 919–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, M., Lombardo, M. V., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2014). Autism. The Lancet, 383(9920), 896–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lecciso, F., Levante, A., Fabio, R. A., Capri, T., Leo, M., Carcagni, P., Distante, C., Mazzeo, P. L., Spagnolo, P., & Petrocchi, S. (2021). Emotional expression in children with ASD: A pre-study on a two-group pre-post-test design comparing robot-based and computer-based training. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 678052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G. T., Xu, S., Feng, H., Lee, G. K., Jin, S., Li, D., & Zhu, S. (2018). An emotional skills intervention for elementary children with autism in China: A pilot study. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 37(2), 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, C., Rutter, M., DiLavore, P. C., Risi, S., Gotham, K., & Bishop, S. L. (2015). ADOS-2. In T. Luque (Adaptadora), Escala de observación para el diagnóstico del autismo—2. Manual (Parte I): Módulos 1–4. TEA Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Lord, C., Rutter, M., & Le Couteur, A. (1994). Autism diagnostic interview—Revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24(5), 659–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loubersac, J., Michelon, C., Ferrando, L., Picot, M. C., & Baghdadli, A. (2023). Predictors of an earlier diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder in children and adolescents: A systematic review (1987–2017). European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 32(3), 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, S., Rivas, R., & Taboada, E. (2009). Revisiones sobre el autismo. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 41, 555–570. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, S., & Yamamoto, J. (2014). Computer-based intervention for inferring facial expressions from the socio-emotional context in two children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(8), 944–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., & Caruso, D. R. (2000). Models of emotional intelligence. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of intelligence (pp. 396–420). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., & Caruso, D. R. (2008). Emotional intelligence: New ability or eclectic traits? American Psychologist, 63(6), 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Málaga, I., Blanco Lago, R., Hedrera-Fernández, A., Álvarez-Álvarez, N., Oreña-Ansonera, V. A., & Baeza-Velasco, M. (2019). Prevalencia de los trastornos del espectro autista en niños en Estados Unidos, Europa y España: Coincidencias y discrepancias. Medicina (Buenos Aires), 79(1), 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Micai, M., Fatta, L., Gila, L., Caruso, A., Salvitti, T., Fulceri, F., Ciaramella, A., D’Amico, R., Del Giovane, C., Bertelli, M., Romano, G., Schünemann, H. J., & Scattoni, M. L. (2023). Prevalence of co-occurring conditions in children and adults with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 155, 105436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagut, M., Mas-Romero, R. M., Fernández, M. I., & Pastor, G. (2018). Influencia del sesgo de género en el diagnóstico de trastorno de espectro autista: Una revisión. Escritos de Psicología (Internet), 11(1), 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, J. A., & Martín, M. L. (2007). La escala de inteligencia de binet y simon (1905) su recepción por la Psicología posterior. Revista de Historia de la Psicología, 28(3), 307–313. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, A. S. (2019). Publication bias-Importance of studies with negative results! Indian Journal of Anaesthesia, 63(6), 505–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omelchenko, I. M., Kobylchenko, V., Dushka, A. L., Suprun, H., & Moiseienko, I. (2024). Educational applications of emotional intelligence for individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Conhecimento & Diversidade, 16(42), 130–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ona, H. N., Larsen, K., Nordheim, L. V., & Brurberg, K. G. (2020). Effects of pivotal response treatment (PRT) for children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD): A systematic review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 7, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrovska, I. V., & Trajkovski, V. (2019). Effects of a computer-based intervention on emotion understanding in children with autism spectrum conditions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(10), 4244–4255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez-Melendez, R., Matamoros, E., Hernandez, D., Mirabel, J., Sanchez, E., & Escude, N. (2022). Music-enhanced emotion identification of facial emotions in autistic spectrum disorder children: A pilot EEG study. Brain Sciences, 12(6), 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcliffe, B., Wong, M., Dossetor, D., & Hayes, S. (2014). Teaching social-emotional skills to school-aged children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A treatment versus control trial in 41 mainstream schools. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(12), 1722–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynoso, C., Rangel, M. J., & Melgar, V. (2017). El trastorno del espectro autista: Aspectos etiológicos, diagnósticos y terapéuticos. Revista Médica del Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, 55(2), 214–222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rice, L. M., Wall, C. A., Fogel, A., & Shic, F. (2015). Computer-assisted face processing instruction improves emotion recognition, mentalizing, and social skills in students with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(7), 2176–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, V., Rivera, A., & Nilo, N. (2019). Actualización en diagnóstico e intervención temprana del Trastorno del Espectro Autista. Revista Chilena de Pediatría, 90(5), 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo-Ponsaran, N. M., Evans-Smith, B., Johnson, J., Russo, J., & McKown, C. (2015). Efficacy of a facial emotion training program for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 40(1), 13–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, M., Mahdavi, A., Sepehr Yeghaneh, S., Abedin, M., & Hajhosseini, M. (2019). The effectiveness of group based acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) on emotion cognitive regulation strategies in mothers of children with autism spectrum. Maedica, 14(3), 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. (1990). Inteligencia emocional. Imaginación, Conocimiento y Personalidad, 9(3), 185–211. [Google Scholar]

- Sari, A. L., Purwaningsih, H., & Istiqomah, N. (2024). Management interventions for enhancing emotional regulation in children with autism spectrum disorders: Scoping review. Observasi: Jurnal Publikasi Ilmu Psikologi, 2(2), 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla, M. D. S. F., Bermúdez, M. O. E., & Sánchez, J. J. C. (2013). Aumento de la prevalencia de los transtornos del espectro autista: Una revisión teórica. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, 1(1), 747–764. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer, R. C., Schmitt, L. M., Reisinger, D. L., Coffman, M., Horn, P., Goodwin, M. S., Mazefsky, C., Randall, S., & Erickson, C. (2022). Regulating together: Emotion dysregulation group treatment for ASD youth and their caregivers. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 53(5), 1942–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N. S., & Pandey, S. (2024). Emotional intelligence (pp. 61–80). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparrow, S. S., & Cicchetti, D. V. (1989). The vineland adaptive behavior scales. In C. S. Newmark (Ed.), Major psychological assessment instruments (Vol. 2, pp. 199–231). Allyn & Bacon. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1989-97306-007 (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Stichter, J. P., Herzog, M. J., Visovsky, K., Schmidt, C., Randolph, J., Schultz, T., & Gage, N. (2010). Social competence intervention for youth with Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism: An initial investigation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(9), 1067–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumra, R., & Sumra, B. (2024). Technology-based interventions for autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Indian Scientific Journal of Research in Engineering and Management, 8(11), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirapu-Ustárroz, J., Pérez-Sayes, G., Erekatxo-Bilbao, M., & Pelegrín-Valero, C. (2007). ¿Qué es la teoría de la mente? Revista de Neurología, 44(8), 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, A. C. Y. (2020). Brief report: Impact of a physical exercise intervention on emotion regulation and behavioral functioning in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(11), 4191–4198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urinovsky, M. G., & Cafiero, P. J. (2022). Tratamientos alternativos y/o complementarios en pacientes con trastorno del espectro autista. Medicina Infantil, 29(2), 139–145. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas, G. C., Cárdenas, J. D., Cabrera, D. M., & León, A. G. (2019). Síndrome de asperger. RECIMUNDO: Revista Científica de la Investigación y el Conocimiento, 3(4), 416–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, M. L., Menhinnitt, R. S., Choi, Y. K., Malacova, E., Eriksson, L., Churchill, A. W., Oddy, B., Boon, K., Randall, C. L., Braun, A., Taggart, J., Marsh, R., & Pun, P. (2024). Comorbidity rates of autism spectrum disorder and functional neurological disorders: A systematic review, meta-analysis of proportions and qualitative synthesis. Autism, 29(2), 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wechsler, D. (2011). Test de inteligencia para Niños WISC IV: Manual técnico y de interpretación (1st ed.). Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Wergeland, G. J. H., Posserud, M.-B., Fjermestad, K., Njardvik, U., & Öst, L.-G. (2022). Early behavioral interventions for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder in routine clinical care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 29(4), 400–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C., Ratcliff, R., Vasey, M., & McKoon, G. (2009). Dysphoria and memory for emotional material: A diffusion-model analysis. Cognition and Emotion, 23(1), 181–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Williams, B. T., Gray, K. M., & Tonge, B. J. (2012). Teaching emotion recognition skills to young children with autism: A randomised controlled trial of an emotion training programme. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(12), 1268–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2023). Autism. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/autism-spectrum-disorders (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Yan, Y., Liu, C., Ye, L., & Liu, Y. (2018). Using animated vehicles with real emotional faces to improve emotion recognition in Chinese children with autism spectrum disorder. PLoS ONE, 13(7), e0200375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, R. L., & Posselt, M. (2012). Using the transporters DVD as a learning tool for children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(6), 984–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, S., Choi, J., Park, S., Bong, G., & Yoo, H. (2017). Social skills training for children with autism spectrum disorder using a robotic behavioral intervention system. Autism Research, 10(7), 1306–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeidan, J., Fombonne, E., Scorah, J., Ibrahim, A., Durkin, M. S., Saxena, S., Yusuf, A., Shih, A., & Elsabbagh, M. (2022). Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism Research, 15(5), 778–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).