Abstract

(1) Background: Teachers’ visual behaviour in classes has an important role in learning and instruction. Hence, understanding the dynamics of classroom interactions is fundamental in educational research. As mapping evidence on this topic would highlight concepts and knowledge gaps in this area, this systematic review aimed to collect and systematise the analysis of teachers’ visual behaviour in classroom settings through the use of eye-tracking apparatus; (2) Methods: The methodological procedures were registered in the INPLASY database and this systematic review used the PRISMA criteria for the selection and analysis of studies in this area. We searched on six literature databases (B-on, ERIC, ScienceDirect, Scopus, TRC and WoS) between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2024. Eligible articles used eye tracking apparatus and analysed teachers’ visual behaviour as a dependent variable in the experiment; (3) Results: The main results of the articles selected (n = 41) points to the differences in teachers’ visual behaviour in terms of professional experience and the relationship between gaze patterns and several classroom variables; (4) Conclusions: A deeper understanding of teachers’ visual behaviour can lead to more effective teacher training and better classroom environments. The scientific research in this area would benefit from more standardized and robust methodologies that allow more reliable analyses of the added value of eye tracking technology.

1. Introduction

Understanding the dynamics of classroom interactions is fundamental in educational research, particularly in the teaching effectiveness’ and student engagement’s context. One critical dimension of this dynamic is the teachers’ visual behaviour during educational activities (Biermann et al., 2023).

Teachers’ gaze patterns offer valuable insights into their instructional focus and responsiveness to students’ needs, as well as classroom management strategies. The emergence of eye-tracking technology has provided an innovative means to objectively measure and analyse these visual behaviours, offering unprecedented depth and precision to understand how teachers visually interact with the classroom environments (Maatta et al., 2021).

Eye-tracking technology has acquired considerable relevance in educational settings. By capturing and quantifying eye movements, saccades and fixations, eye-tracking apparatus enables scientific researchers to decode visual attention and cognitive processes (Ashraf et al., 2018).

This methodological advancement has considerable implications for educational investigation, particularly in examining how teachers allocate their visual attention across the various classroom stimuli, such as students, instructional materials and classroom management tasks, making eye tracking a powerful tool for studying teachers’ decision-making processes and how they process classroom behaviour (Beach & McConnel, 2019). These analyses can illuminate the cognitive underpinnings of teaching practices and potentially inform strategies for teacher training and professional development (Keskin et al., 2023).

Teachers’ visual behaviour has an important role in learning and instruction (Chen, 2024). Visual attention is integral to how teachers navigate complex classroom environments. Additionally, gaze has a communicative and social function in interactions, suggesting that how and where teachers look can influence classroom dynamics and student engagement. By integrating these ideas, the analysis of teachers’ gaze patterns through eye-tracking technology can offer comprehensive insights into teaching’s multifaceted nature (Telgmann & Müller, 2023).

The expanded relevance of eye-tracking research in pedagogy-oriented disciplines, where understanding visual attention can provide critical insights into teaching and learning processes, demonstrated how teachers’ and students’ gaze behaviour influences knowledge acquisition and classroom interactions. These investigations have revealed rich findings, such as how expert teachers distribute their attention differently than novices or how specific visual cues can enhance student engagement and comprehension (Horlenko et al., 2024; Seidel et al., 2021).

Furthermore, eye-tracking studies in pedagogical contexts have explored the impact of teachers’ visual attention patterns in their students’ learning effectiveness and participation levels, as a stimulus and a key guide to the learners (Kwon et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2023).

Despite the integration of eye-tracking technology in educational research offers a promising avenue for uncovering the complexities of teachers’ visual behaviour in classroom settings and the growing interest in this research domain, existing studies remain fragmented. Variations in research methodologies, analytical approaches or sample populations have resulted in a heterogeneous body of literature (Witt et al., 2024).

This variety makes it the development of a cohesive understanding of how teachers’ visual attention influences instructional effectiveness and students’ outcomes difficult. Moreover, discrepancies in experimental designs and the metrics analysed further complicate the synthesis of findings across studies. These methodological divergences underscore the need for a systematic review to aggregate the existing research (Ashraf et al., 2018).

A systematic review of teachers’ visual behaviour using eye-tracking apparatus is, therefore, both timely and necessary. Such a review of the emerging body of literature is essential to consolidate and provide a structured synthesis of existing knowledge, identifying and highlighting methodological trends and gaps on how eye-tracking technology has been applied to study teachers’ gaze patterns. It can also contribute to elucidate the methodological strengths and limitations in this field, guiding future research towards more robust and standardised scientific investigation approaches (Skuballa & Jarodzka, 2022).

Additionally, by identifying consistent patterns in teachers’ visual behaviour, this review can provide evidence-based practices for teacher education and professional development, ultimately aiming to enhance, not only teaching effectiveness, but also student learning experiences (Nückles, 2021).

By synthesising the main findings from the observational and experimental studies, this review seeks to examine how teachers distribute their visual attention, the factors influencing their gaze patterns and the implications of these behaviours for instructional practice, providing a comprehensive understanding of the current state of research in this field from the last ten years, offering insights that can bridge the gap between empirical evidence and practical application in educational contexts.

In view of the above, the aim of this systematic review is to collect and systematise the analysis of teachers’ visual behaviour in classroom settings through the use of eye-tracking technology apparatus.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

This systematic review used the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis” (PRISMA) to select and analyse the studies initially identified (Page et al., 2022). The methodological procedures were registered in the “International Platform of Registered Systematic Review and Meta-analysis” database under the registration number INPLASY2024120086. As a result of the bibliographical research carried out and analysed, it was necessary to change the protocol once.

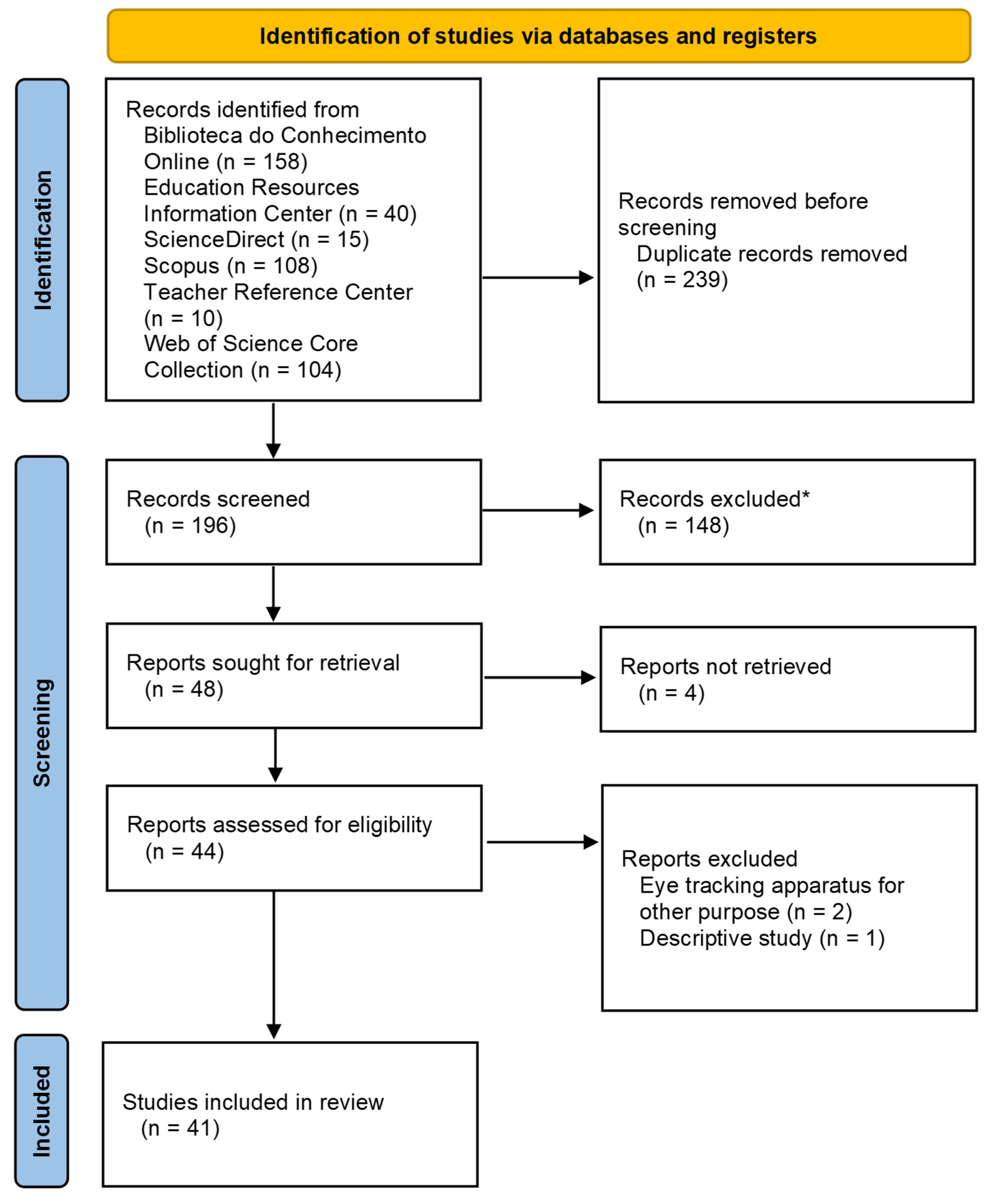

A search was conducted in six databases: Biblioteca do Conhecimento Online, Educational Resource Information Center, ScienceDirect, Scopus, Teacher Reference Center and Web of Science Core Collection. The terms (“eye tracking” OR “eye tracker”) AND (“teacher” OR “teaching”) AND (“visual behaviour” OR “visual focus” OR “visual attention” OR “eye gaze” OR “professional vision”) used were searched for in the titles, abstracts and keywords (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases and registers only (* Table S1).

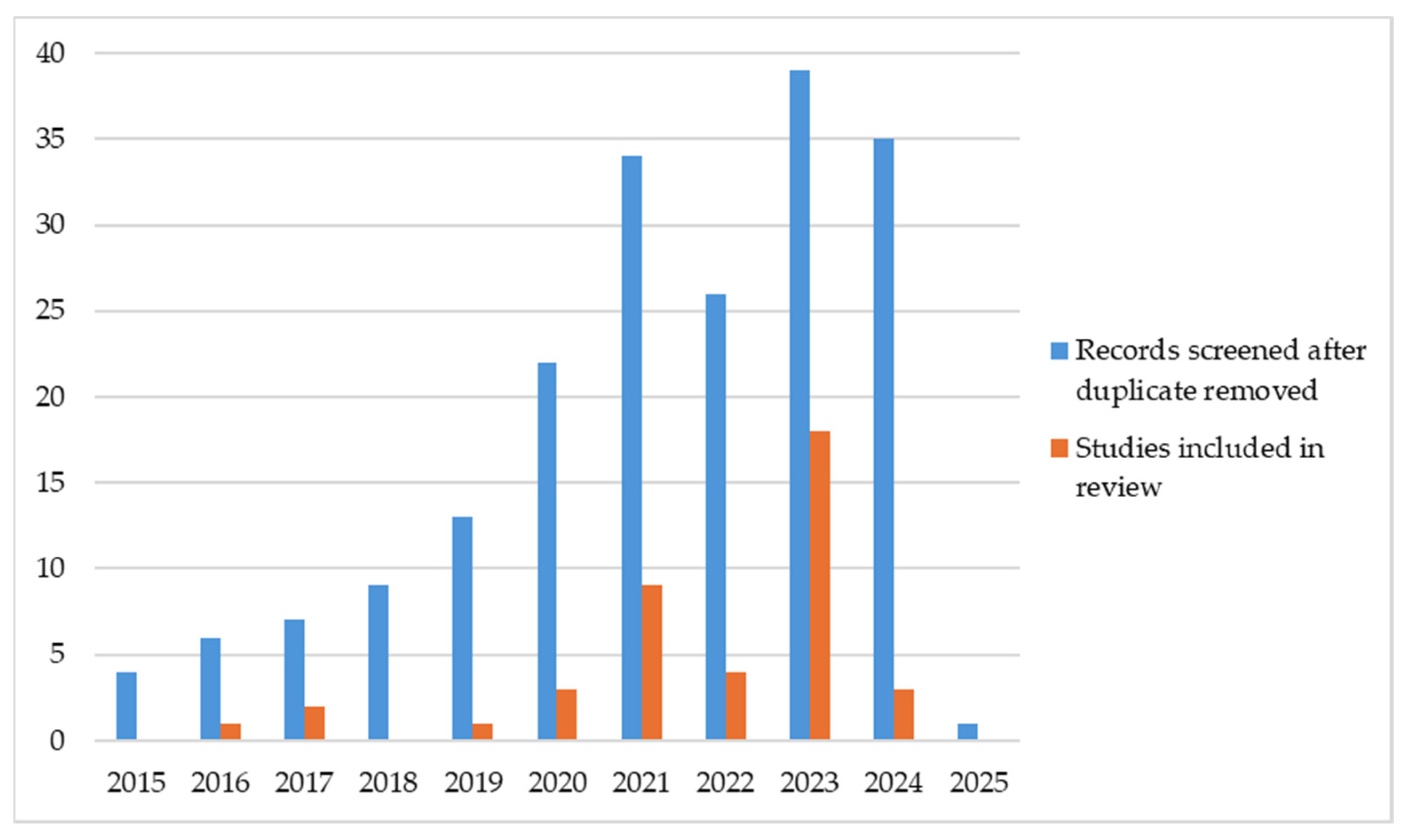

To broaden the spectrum of results (Ashraf et al., 2018; Witt et al., 2024), the time span of the research developed was between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2024 (Figure 2). Afterwards, the main cross-references of the articles included in the systematic review were scanned.

Figure 2.

Number of articles included by year of publication.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria in this review were the following: (i) published works between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2024, (ii) works written in English, Portuguese, Spanish or French, (iii) articles published in peer-reviewed journals, (iv) articles in full-text, (v) research that used eye tracking apparatus and (vi) research where teachers’ visual behaviour was one of the dependent variables in the experiment.

These languages and the timespan of the research cover the articles that will be a reference in this area of knowledge and there is no reason to think that grey literature makes significant contributions to the review. Also, it was ensured that all included studies could be fully and critically analysed by the authors, minimising the risk of misinterpretation due to translation barriers.

The following criteria were used for exclusion: (i) published works outside the timespan selected, (ii) works written in languages other than those selected, (iii) academic theses, books, opinion articles, conference papers and non-scientific articles (iv) articles without full-text, (v) research that didn’t use eye tracking apparatus and (vi) research where eye tracking apparatus was used in the experiment for a purpose other than the intended (Supplementary Materials).

The article selection process followed the following steps: (i) studies that used the descriptors in the aforementioned databases, (ii) exclusion of duplicate articles, (iii) reading of the titles, abstracts and keywords and (iv) critical reading and assessment of the articles.

The selection and extraction of data from the articles was carried out in three stages. First, two authors (R.M. and M.P.) independently selected eligible articles. Second, the same authors independently extracted the previously defined information. In both stages, a consensus of more than 90% was reached between these two authors, when comparing the analyses. If necessary, in case of disagreements, a third author (G.D.) was called to analyse and issue his final decision. Third, after achieving this homogeneity of criteria in more than 10% of the articles, one author (R.M.) completed the collection of the remaining eligible articles and information.

2.3. Quality Assessment

The “STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology” (STROBE) tool was used by two authors (R.M. and M.P.) to independently assess the quality of the non-randomized studies included (Cuschieri, 2019). Again, after achieving a homogeneity of criteria superior to 90% in more than 10% of eligible articles, one author (R.M.) completed the assessment.

This checklist aims to ensure a clear presentation of what was planned and conducted in an observational study, the assessment being composed of a total of 22 items. This procedure would not be a condition for the study to be included, but rather to identify the ones in which poor-quality assessment could interfere with the outcomes.

3. Results

For this systematic review, 41 articles with observational designs were selected. Table 1 shows the main outcomes of each one that will be analysed below.

Table 1.

Main outcomes of the articles included.

Table 2 shows the detailed quality assessment of the studies included according to STROBE checklist’s items.

Table 2.

Quality assessment of the articles included.

Analysing Figure 2, it can be seen that the vast majority of the studies selected were published in the last five years, suggesting that this topic is still exploratory.

It is assumed that the core aim of them included is to investigate teachers’ visual behaviour in classroom settings. Nevertheless, the independent variables observed and analysed encompass a significant diversity.

For example, several studies (Huang et al., 2023; Teo & Pua, 2023) compare the visual strategies in terms of teaching experience (between novice and experienced teachers or trainers and teachers in training), other focus on the relationship between teacher visual attention and students’ characteristics, academic performance or behaviour (ethnicity, special educational needs, hand raising movements, among other factors).

Another example are studies exploring the effect of pedagogical training interventions on teachers’ visual behaviour, as well as the effect of factors such as stress, teaching practices (e.g., type of instruction, classroom and dialogue approaches or teaching settings), or even the video visualization perspective or the use of virtual reality technologies (Minarikova et al., 2021; Wyss et al., 2023).

Some studies (Kaminskienė et al., 2023; Kwon et al., 2017) include the students’ visual perspective as a way of helping to understand teachers’ visual behaviour, while others focus more on the analyses of eye tracking technology as a tool to help self-reflection, with different types of videos and apparatus, with their different impact on the interpretation of teachers’ visual attention and cognitive engagement.

Regarding this last point, in fact, a wide heterogeneity of methodologies used to evaluate teachers’ visual behaviour was found. Studies employing mobile eye-tracking glasses offer a naturalistic approach by capturing real-time gaze data in authentic classroom environments. These tools allow researchers to examine how teachers allocate visual attention while actively engaging with the authentic class (Duvivier et al., 2024; Kosko et al., 2024).

Additionally, other investigations incorporated screen-based eye trackers in controlled simulations or video analysis to assess visual behaviour retrospectively. These approaches are particularly useful to provide detailed patterns in teachers’ gaze behaviour, not invalidating the ecological validity of the studies (Chaudhuri et al., 2023; Horlenko et al., 2024).

The eye-tracking technology research analysed provided various metrics (e.g., fixation counts, durations and time to first fixation), which are all used to determine teacher gaze behaviour. Mobile eye-tracking is particularly useful for capturing teachers’ in-action gaze patterns. Video analysis is also a useful way to study teachers’ professional vision, often combined with eye-tracking data. Additionally, the use of standardised classroom simulations helps to control variations and make comparisons more meaningful (Coskun & Cagiltay, 2021; Weigelt & Ben-Aharon, 2023).

The studies (Keller et al., 2022; Wyss et al., 2021) predominantly use quantitative methods and all, as an inclusion criterion, include eye-tracking observation. However, the methodological approaches, as mentioned, varies between real classrooms and in simulations (video analysis with or without teacher commentary).

Other measurements include gathering data on teaching conceptions, stress, attitudes, self-efficacy and other relevant factors, interviews to collect qualitative data on teachers’ perceptions and reflections, post think-aloud analysis where participants verbalize their thoughts while performing a task or tests to evaluate teachers’ pedagogical-psychological knowledge (Grub et al., 2022).

The studies contained encompass a wide variety of educational levels, from early childhood to university context [nursery (n = 1), primary school (n = 10), middle school (n = 12), high school (n = 10) and university (n = 5)], as well as the subjects (e.g., Mathematics, Science, Geography or History).

The main results and outcomes, which will be developed later in this papers’ Discussion, reveal some consistent patterns. In terms of professional experience, older teachers use more dynamic visual strategies, with more frequent revisits and shorter fixations and focus more quickly on students off-task, while novice tend to concentrate on superficial aspects (Shinoda et al., 2021).

As expected, other important insights reveal that teachers’ visual behaviour is associated with or influenced by some variables, such as students’ academic skills or profiles of commitment to tasks, teacher stress (negatively affects their visual attention to students) and teaching approach (student-centred practices improve the distribution of this attention) (Chaudhuri et al., 2023).

Other studies (Haataja et al., 2019; Heinonen et al., 2023) indicated that teachers’ visual attention varies with their intentions and support strategies and can affect students’ engagement, motivation and satisfaction and that training interventions can improve teachers’ ability to identify and respond to classroom management events. In a direct way, visual attention seems to affect the quality of teaching and learning.

Studies in general (e.g., Haataja et al., 2019; Telgmann & Müller, 2023; Wyss et al., 2023) highlight the importance of eye tracking as a tool for investigating teachers’ visual behaviour and the development of professional vision the influence of experience. Pedagogical training, the need to consider teachers’ didactics filiation and individual differences and the triangulation of appropriate metrics are also mentioned as crucial to understanding the underlying reasoning and developing teachers’ visual attention.

The potential publication bias, where studies reporting significant findings may be more likely to be published than those with inconclusive results, must be considered. Another important factor is the variation in sample populations across studies, such as differences in participants’ teaching experience or subject expertise, aspects that can influence how visual attention is allocated in classroom settings and may limit the generalisability of findings to the teaching context. Nevertheless, this summary of results establishes a solid base for further analysis and for the discussion of the topic of teachers’ professional vision and the importance of eye tracking in research on teaching and learning.

4. Discussion

The integration of eye-tracking technology into educational research has provided unprecedented insights into the complexities of teachers’ visual behaviour within classroom settings.

This systematic review of the literature reveals consistent patterns and variations in how teachers allocate their visual attention, which are closely linked to their experience, training and pedagogical approaches. This section delves into the main findings, exploring the differences between experienced and novice teachers, the influence of various factors on gaze patterns and the implications for teacher training and classroom management.

4.1. Teaching Experience

Some studies have investigated how teachers’ visual behaviour relates to student performance, often comparing teachers with varying levels of experience (Kosko et al., 2024; Seidel et al., 2021). The research consistently shows that experienced teachers exhibit different visual strategies compared to novice or pre-service teachers, which can relate to their competence in assessing students and managing classrooms (Murtonen et al., 2023; Wolff et al., 2016).

In relation to their scanpaths and gaze patterns, expert teachers tend to have more complex and recurring ones, often monitoring multiple students more regularly (Kosel et al., 2021). They distribute their gaze more evenly across the classroom and return to previously observed students (Grub et al., 2022), suggesting a consistent and student-oriented approach.

With regard to fixation duration and frequency, although there are some contradictory findings, some studies suggest experienced teachers have shorter fixation durations and more frequent fixations on relevant areas (Kosel et al., 2023). This indicates that experts can process visual information more quickly and efficiently than novices (Sokolová et al., 2022). However, other studies have not found significant differences in the number of fixations across professional experience levels (Biermann et al., 2023; Jarodzka et al., 2023).

It is also revealed that expert teachers exhibit more complex visual behaviour, which involves monitoring each student more frequently and shifting gaze between all possible student combinations (Kosel et al., 2021). All these statements have an impact on assessment competence and students’ and classroom events’ management.

In terms of the attention given to students, experienced teachers demonstrate a student-centred gaze, focusing more on students and their engagement (Sadamatsu, 2023). They are more likely to visually attend to students who require additional support or who exhibit specific behaviours (Murtonen et al., 2023).

Expert teachers also are more proficient at noticing relevant classroom events, such as student misbehaviour or critical incidents, and are better at separating task-relevant information from task-redundant information. They can identify and respond more quickly to problematic behaviours (Duvivier et al., 2024).

The assessment accuracy of students’ characteristics by teachers with more complex gaze patterns and more equal monitoring of students tends to be better. This suggests that the visual strategies employed by expert teachers support their ability to assess students effectively (Kosel et al., 2023).

Finally, considering classroom management, experienced teachers can better manage classroom dynamics through visual attention, proactively scanning the classroom and responding to student behaviour (Kosel et al., 2021). They effectively distribute their visual attention across all students. Some studies also indicate that experienced teachers are also more able to refocus their attention on relevant aspects after a distraction (Duvivier et al., 2024).

4.2. Trainee and Novice Teachers

Other studies analyse exclusively the visual behaviour of trainee or early career teachers, revealing significant insights into how they visually attend to classroom events (Gabel et al., 2023; Schnitzler et al., 2020). Novice teachers display higher variance in the frequency and duration of their eye movements compared to experienced teachers. This is in line with the struggle to focus their attention on information relevant to learning processes, frequently fixing themselves on non-essential aspects of classroom management, due to the difficulty in distributing their attention among all the students in accordance with the requirements of effective teaching and learning (Stürmer et al., 2017).

Therefore, novice teachers may focus their undivided attention on particular students or instructional materials. They may also be driven by salient features in student behaviour rather than an intention to diagnose students’ cognitive processes. This can result in missing critical events or students who require special attention (Goldberg et al., 2021).

When analysing teacher-student interactions, it was found that novice teachers are more likely to focus on students exhibiting active, engaged behaviours. Conversely, they might miss students with less obvious cues of engagement, such as the ones who are struggling, underestimating their abilities, or not interested in the topic (Goldberg et al., 2021).

4.3. Other Contextual Variables

There are other specific factors analysed in some of the articles included in relation to visual behaviour, such as, for example, the teaching practices or the students’ characteristics and profile (Chaudhuri et al., 2022; Smidekova et al., 2020).

Teachers do not distribute their visual attention evenly among all students. In this sense, students who actively participate verbally in classes’ activities tend to receive more visual attention from teachers compared to silent students. However, in high-quality educational dialogues, teachers tend to distribute their attention more broadly across students, indicating that effective teaching involves a more inclusive visual focus (Muhonen et al., 2020).

Expert teachers also tend to have a student-centred gaze, focusing on areas of the classroom that are rich in information, observing the entire classroom and visually attending to students more than to other objects and automatically monitor classroom activity in terms of student engagement and learning (Stahnke & Blömeke, 2021).

About the student behaviour, teachers tend to pay more attention to disruptive or off-task behaviour (Kosel et al., 2023). However, when considering self-regulated learning, they seem to focus more on salient behaviours, such as searching for information, than on less visible cognitive and metacognitive regulation behaviours (Horlenko et al., 2024).

Teachers’ pedagogical intentions also guide their visual attention. For example, during affective scaffolding, teachers focus more on student faces when their intentions are to motivate students and reduce frustration. In this sense, teachers also prioritize student presence during instruction-giving in general (Maatta et al., 2021).

These results have an impact on students’ outcomes. When teachers show a balance of gazing at students and teaching content, students tend to be more engaged and motivated, leading to higher satisfaction (Yang et al., 2023). Conversely, when teachers focus more on their own teaching and pedagogical aspects, they tend to focus less on individual students (Muhonen et al., 2023).

The research also underscores the significance of knowledge and training in developing effective visual strategies. It is argued that teachers’ visual perception is largely driven by top-down processes. This means that these professionals’ gaze is guided by their knowledge, experience and cognitive schemas, rather than eye-catching stimuli (Kosel et al., 2023).

Experienced teachers develop knowledge-informed cognitive schemas, which allow them to process and prioritise visual information more effectively. Their capacity to notice relevant classroom features is closely linked to their professional knowledge. Novice teachers often lack the knowledge base to guide their visual attention effectively (Stahnke & Friesen, 2023).

The interpretation of global measures of visual attention may not always remains a complex and not always a straightforward process, therefore event-related noticing underscores the need for specific pedagogic training to ensure robust interpretations of eye-tracking findings in educational research (Schindler & Lilienthal, 2019). Additionally, combining eye-tracking with other variables, such as think-aloud protocols and analysis of student cues, can give a more comprehensive understanding of the cognitive and behavioural activities driving teacher judgements.

4.4. Limitations of the Included Studies

While this review provides valuable insights into teachers’ visual behaviour, several limitations must be acknowledged. The heterogeneity of study designs (e.g., sample populations, methodological procedures and subject taught or other contextual factors) makes direct comparisons between findings difficult. This wide variation might impact the validity and reliability of results, limiting generalisability and making it necessary to formulate and interpretate conclusions cautiously (Witt et al., 2024).

Additionally, in order to fully capture the cognitive and pedagogical decision-making processes of teachers, combining eye-tracking with qualitative methods, such as think-aloud protocols or retrospective interviews, could enhance understanding by analysing gaze patterns with teachers’ reflective insights (Biermann et al., 2023; Muhonen et al., 2023).

5. Conclusions

This systematic review of studies points to a trend in which analysing teachers’ visual behaviour through eye-tracking technology provides valuable insights into the complexities of classroom interactions.

The research highlights, not only that experienced teachers demonstrate more effective and efficient visual strategies that benefit their classroom management and assessment capabilities, linked to the development of cognitive domain and professional vision, but also that the integration of eye-tracking data with other methods provides a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between teachers’ visual attention and student outcomes. In this sense, teachers’ gaze patterns are a key aspect of their professional competence.

In terms of practical implications, as eye-tracking research highlights key areas where inexperienced teachers might struggle with, a deeper understanding of their behaviour can lead to more effective teacher training and better classroom environments for students. Methodological decisions must be carefully considered in this field and should include triangulation of methods and measures and an ecological view of the research, in order to promote more effective pedagogic training for teachers, particularly for novice educators.

The year of publication of the vast majority of the selected studies suggests that this topic is still exploratory, showing that it can and should be investigated in depth. Other limitations of this systematic review, such as the wide variation in educational contexts, which may influence how teachers allocate visual attention and interact with students can be overcome with studies bringing together more robust methodologies thus allowing more reliable analyses of the added value of the eye tracking technology.

It is suggested, not only to establish standardised methodologies in the field, carrying out research with similar apparatus and manipulated variables, as being essential to analyse both global and event-related measures of noticing, but also to use larger and more diverse sample sizes to enhance the generalizability of findings and integrate other data sources (e.g., think-aloud protocols), to provide a more comprehensive understanding strengthen the validity of the results.

Looking to future research, there is the need to investigate how pedagogic training interventions that promote classroom management knowledge can positively impact pre-service teachers’ ability to identify relevant classroom events. Also, due to the lack found and although video observations are still valid and have some strengths, as the authenticity of the learning environment may shape visual behaviour, there is a need for more studies on how teachers’ visual attention operates during actual teaching.

Finally, it is important to investigate other potential confounding variables, such as how teacher education can promote the application of classroom management knowledge to improve teachers’ noticing during their own teaching, allowing for adjustments that enhance student interaction and learning outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ejihpe15040054/s1, Table S1: Reason for excluding the articles identified in the first “Screening” phase.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M. and G.D.; methodology, R.M. and M.P.; software, R.M. and M.P.; validation, R.M., P.N. and G.D.; formal analysis, R.M., G.D. and M.P.; investigation, R.M., G.D. and M.P.; resources, R.M., G.D. and M.P.; data curation, R.M., G.D. and M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, R.M., P.N. and G.D.; writing—review and editing, R.M., P.N. and G.D.; visualization, R.M., P.N. and G.D.; supervision, R.M., G.D. and M.P.; project administration, not applicable; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

As a systematic review, the Institutional Review Board Statement does not apply. However, the subsequent experimental scientific studies, which are already underway, have been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Sports Sciences and Physical Education, University of Coimbra (reference CE/FCDEF-UC/00142024).

Informed Consent Statement

As a systematic review, the Informed Consent Statement does not apply. However, the subsequent experimental scientific studies, which are already underway, have been approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Sports Sciences and Physical Education, University of Coimbra (reference CE/FCDEF-UC/00142024).

Data Availability Statement

We will share the research data with MDPI.

Acknowledgments

Technical support: Rui Mendes (Polytechnic Institute of Coimbra, Coimbra Education School, Coimbra, Portugal; SPRINT Sport Physical Activity and Health Research & Innovation Center).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ashraf, H., Sodergren, M. H., Merali, N., Mylonas, G., Singh, H., & Darzi, A. (2018). Eye-tracking technology in medical education: A systematic review. Medical Teacher, 40(1), 62–69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Beach, P., & McConnel, J. (2019). Eye tracking methodology for studying teacher learning: A review of the research. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 42(5), 485–501. [Google Scholar]

- Biermann, A., Brünken, R., Lewalter, D., & Grub, A. (2023). Assessment of noticing of classroom disruptions: A multi-methods approach. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1266826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, S., Muhonen, H., Pakarinen, E., & Lerkkanen, M. (2022). Teachers’ visual focus of attention in relation to students’ basic academic skills and teachers’ individual support for students: An eye-tracking study. Learning & Individual Differences, 98, 102179. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri, S., Pakarinen, E., Lerkkanen, M., & Jõgi, A. (2023). Teaching practices mediating the effect of teachers’ psychological stress, and not physiological on their visual focus of attention. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1283701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. (2024). The application of eye-tracking technology in chemistry education research: A systematic review. Research in Science & Technological Education, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskun, A., & Cagiltay, K. (2021). Investigation of classroom management skills by using eye-tracking technology. Education and Information Technologies, 26(3), 2501–2522. [Google Scholar]

- Cuschieri, S. (2019). The STROBE guidelines. Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia, 13(1), 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Duvivier, V., Derobertmasure, A., & Demeuse, M. (2024). Eye tracking in a teaching context: Comparative study of the professional vision of university supervisor trainers and pre-service teachers in initial training for secondary education in French-speaking Belgium. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1326752. [Google Scholar]

- Gabel, S., Keskin, Ö., Gegenfurtner, A., Kollar, I., & Lewalter, D. (2023). Guiding pre-service teachers’ visual attention through instructional settings: An eye-tracking study. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1282848. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, P., Schwerter, J., Seidel, T., Müller, K., & Stürmer, K. (2021). How does learners’ behavior attract preservice teachers’ attention during teaching? Teaching and Teacher Education, 97, 103213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grub, A., Biermann, A., Lewalter, D., & Brünken, R. (2022). Professional vision and the compensatory effect of a minimal instructional intervention: A quasi-experimental eye-tracking study with novice and expert teachers. Frontiers in Education, 7, 890690. [Google Scholar]

- Haataja, E., Moreno-Esteva, E. G., Salonen, V., Laine, A., & Hannula, M. (2019). Teacher’s visual attention when scaffolding collaborative mathematical problem solving. Teaching and Teacher Education, 86, 102877. [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen, N., Katajavuori, N., & Södervik, I. (2023). University teachers’ professional vision with respect to their conceptions of teaching and learning: Findings from an eye-tracking study. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1232273. [Google Scholar]

- Horlenko, K., Kaminskiene, L., & Lehtinen, E. (2024). Student self-regulated learning in teacher professional vision: Results from combining student self-reports, teacher ratings, and mobile eye tracking in the high school classroom. Frontline Learning Research, 12(2), 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Richter, E., Kleickmann, T., Scheiter, K., & Richter, D. (2023). Body in motion, attention in focus: A virtual reality study on teachers’ movement patterns and noticing. Computers & Education, 206, 104912. [Google Scholar]

- Jarodzka, H., van Driel, S., Catrysse, L., & Crasborn, F. (2023). Classroom chronicles: Through the eyeglasses of teachers at varying experience levels. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1280766. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminskienė, L., Horlenko, K., Matulaitienė, J., Ponomarenko, T., Rutkienė, A., & Tandzegolskienė-Bielaglovė, I. (2023). Mobile eye tracking evoked teacher self-reflection about teaching practices and behavior towards students in higher education. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1209856. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, L., Cortina, K., Miller, K., & Müller, K. (2022). Noticing and weighing alternatives in the reflection of regular classroom teaching: Evidence of expertise using mobile eye-tracking. Instructional Science, 50(2), 251–272. [Google Scholar]

- Keskin, Ö., Gabel, S., Gegenfurtner, A., & Kollar, I. (2023). Relations between pre-service teacher gaze, teacher attitude, and student ethnicity. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1272671. [Google Scholar]

- Kosel, C., Böheim, R., Schnitzler, K., Holzberger, D., Pfeffer, J., Bannert, M., & Seidel, T. (2023). Keeping track in classroom discourse: Comparing in-service and pre-service teachers’ visual attention to students’ hand-raising behavior. Teaching and Teacher Education, 128, 104142. [Google Scholar]

- Kosel, C., Seidel, T., & Holzberger, D. (2021). Identifying expert and novice visual scanpath patterns and their relationship to assessing learning-relevant student characteristics. Frontiers in Education, 5, 612175. [Google Scholar]

- Kosko, K., Ferdig, R., Lenart, C., Heisler, J., & Guan, Q. (2024). Exploring teachers’ eye-tracking data and professional noticing when viewing a 360 video of elementary mathematics. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S., Kim, D., Lee, Y., & Kwon, Y. (2017). Visual attention of science class: An eye-tracking case study of student and teacher. Information, 20(9), 6679–6686. [Google Scholar]

- Maatta, O., McIntyre, N., Palomäki, J., Hannula, M. S., Scheinin, P., & Ihantola, P. (2021). Students in sight: Using mobile eye-tracking to investigate mathematics teachers’ gaze behaviour during task instruction-giving. Frontline Learning Research, 9(4), 92–115. [Google Scholar]

- Minarikova, E., Smidekova, Z., Janik, M., & Holmqvist, K. (2021). Teachers’ professional vision: Teachers’ gaze during the act of teaching and after the event. Frontiers in Education, 6, 716579. [Google Scholar]

- Muhonen, H., Pakarinen, E., & Lerkkanen, M. (2023). Professional vision in the classroom: Teachers’ knowledge-based reasoning explaining their visual focus of attention to students. Teaching and Teacher Education, 121, 103907. [Google Scholar]

- Muhonen, H., Pakarinen, E., Rasku-Puttonen, H., & Lerkkanen, M. (2020). Dialogue through the eyes: Exploring teachers’ focus of attention during educational dialogue. International Journal of Educational Research, 102, 101607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtonen, M., Anto, E., Laakkonen, E., & Vilppu, H. (2023). University teachers’ focus on students: Examining the relationships between visual attention, conceptions of teaching and pedagogical training. Frontline Learning Research, 10(2), 64–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nückles, M. (2021). Investigating visual perception in teaching and learning with advanced eye-tracking methodologies: Rewards and challenges of an innovative research paradigm. Educational Psychology Review, 33, 149–167. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M., Moher, D., & McKenzie, J. (2022). Introduction to PRISMA 2020 and implications for research synthesis methodologists. Research Synthesis Methods, 13(2), 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadamatsu, J. (2023). Experienced nursery teachers gaze longer at children during play than do novice teachers: An eye-tracking study. Asia Pacific Education Review, 24(4), 577–589. [Google Scholar]

- Schindler, M., & Lilienthal, A. J. (2019). Domain-specific interpretation of eye tracking data: Towards a refined use of the eye-mind hypothesis for the field of geometry. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 101, 123–139. [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzler, K., Holzberger, D., & Seidel, T. (2020). Connecting judgment process and accuracy of student teachers: Differences in observation and student engagement cues to assess student characteristics. Frontiers in Education, 5, 602470. [Google Scholar]

- Seidel, T., Schnitzler, K., Kosel, C., Stürmer, K., & Holzberger, D. (2021). Student characteristics in the eyes of teachers: Differences Between novice and expert teachers in judgment accuracy, observed behavioral cues, and gaze. Educational Psychology Review, 33(1), 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinoda, H., Yamamoto, T., & Imai-Matsumura, K. (2021). Teachers’ visual processing of children’s off-task behaviors in class: A comparison between teachers and student teachers. PLoS ONE, 16(11), e0259410. [Google Scholar]

- Skuballa, I., & Jarodzka, H. (2022). Professional vision at the workplace illustrated by the example of teachers: An overview of most recent research methods and findings. In C. Harteis, D. Gijbels, & E. Kyndt (Eds.), Research approaches on workplace learning: Professional and practice-based learning (Volume 31, pp. 117–136). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Smidekova, Z., Janik, M., Minarikova, E., & Holmqvist, K. (2020). Teachers’ gaze over space and time in a real-world classroom. Journal of Eye Movement Research, 13(4), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolová, L., Lemesová, M., Hlavác, P., & Harvanová, S. (2022). Through teachers’ eyes: An eye-tracking study of classroom interactions. Sodobna Pedagogika-Journal of Contemporary Educational Studies, 73(4), 127–145. [Google Scholar]

- Stahnke, R., & Blömeke, S. (2021). Novice and expert teachers’ noticing of classroom management in whole-group and partner work activities: Evidence from teachers’ gaze and identification of events. Learning and Instruction, 74, 1101464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahnke, R., & Friesen, M. (2023). The subject matters for the professional vision of classroom management: An exploratory study with biology and mathematics expert teachers. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1253459. [Google Scholar]

- Stürmer, K., Seidel, T., Häusler, J., Müller, K., & S. Cortina, K. (2017). What is in the eye of preservice teachers while instructing? An eye-tracking study about attention processes in different teaching situations. Zeitschrift fur Erziehungswissenschaft, 20, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telgmann, L., & Müller, K. (2023). Training & prompting pre-service teachers’ noticing in a standardized classroom simulation—A mobile eye-tracking study. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1266800. [Google Scholar]

- Teo, T., & Pua, C. Y. (2023). Transitions from presence, belonging to engaged participation in an inclusive classroom: An eye-tracking study. Pedagogies, 18(3), 473–496. [Google Scholar]

- Weigelt, H., & Ben-Aharon, O. (2023). Teaching on zoom in the eyes of the lecturer: An eye tracking study. Ubiquity Proceedings, 3(1), 168–175. [Google Scholar]

- Witt, J., Schorer, J., Loffing, F., & Roden, I. (2024). Eye-tracking research on teachers’ professional vision: A scoping review. Teaching and Teacher Education, 144, 104568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, C., Jarodzka, H., Boshuizen, H., & van den Bogert, N. (2016). Teacher vision: Expert and novice teachers’ perception of problematic classroom management scenes. Instructional Science, 44(3), 243–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyss, C., Bäuerlein, K., & Mahler, S. (2023). Pre-service and in-service teachers’ professional vision depending on the video perspective—What teacher gaze and verbal reports can tell us. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1282992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyss, C., Rosenberger, K., & Bührer, W. (2021). Student teachers’ and teacher educators’ professional vision: Findings from an eye tracking study. Educational Psychology Review, 33(1), 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J., Liu, C., Zhang, Y., Yu, Q., & Pi, Z. (2023). The teacher’s eye gaze in university classrooms: Evidence from a field study. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 60(1), 4–14. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).