Using Kerosene as an Auxiliary Collector to Recover Gold from Refractory Gold Ore Based on Mineralogical Characteristics

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

2.2. Mineral Technology Methods

2.3. Floatation Methods

3. Results

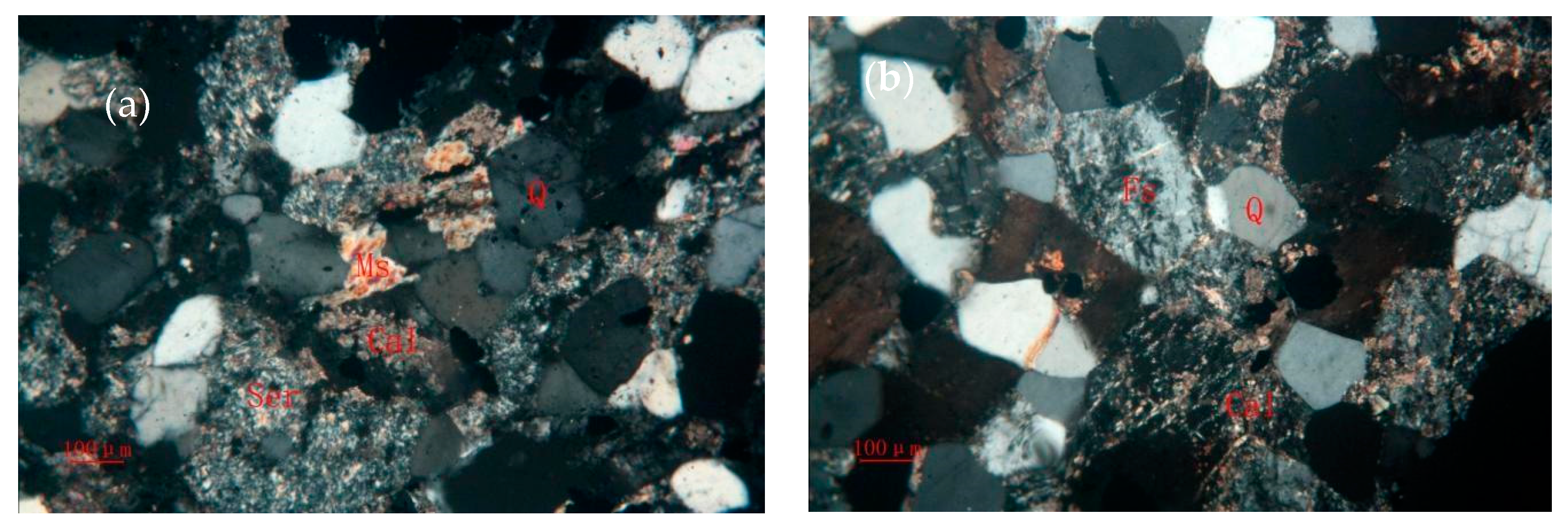

3.1. Ore Components and Mineral Characteristics

3.1.1. Gold

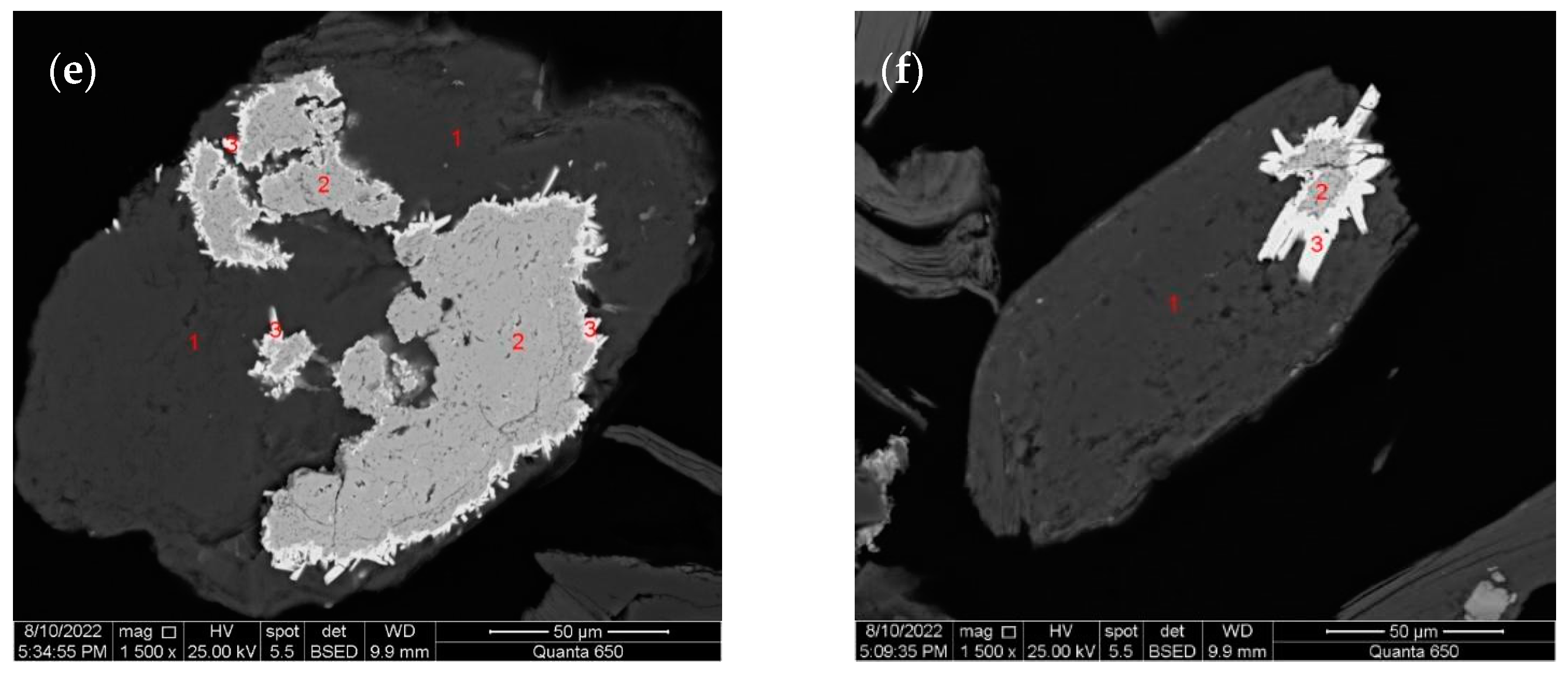

3.1.2. Pyrite

3.1.3. Arsenopyrite

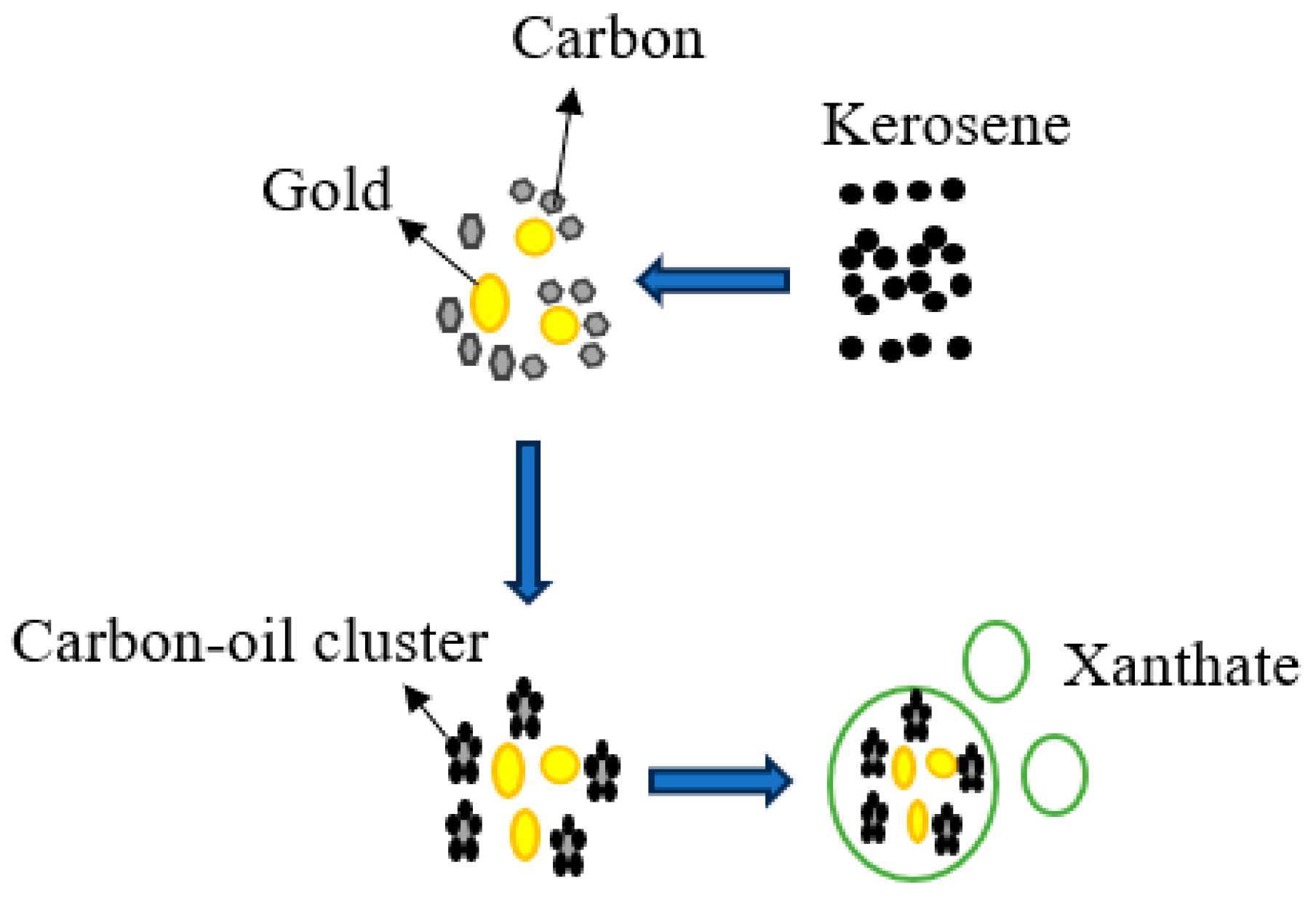

3.1.4. Carbon

3.1.5. Quartz

3.2. Floatation Tests

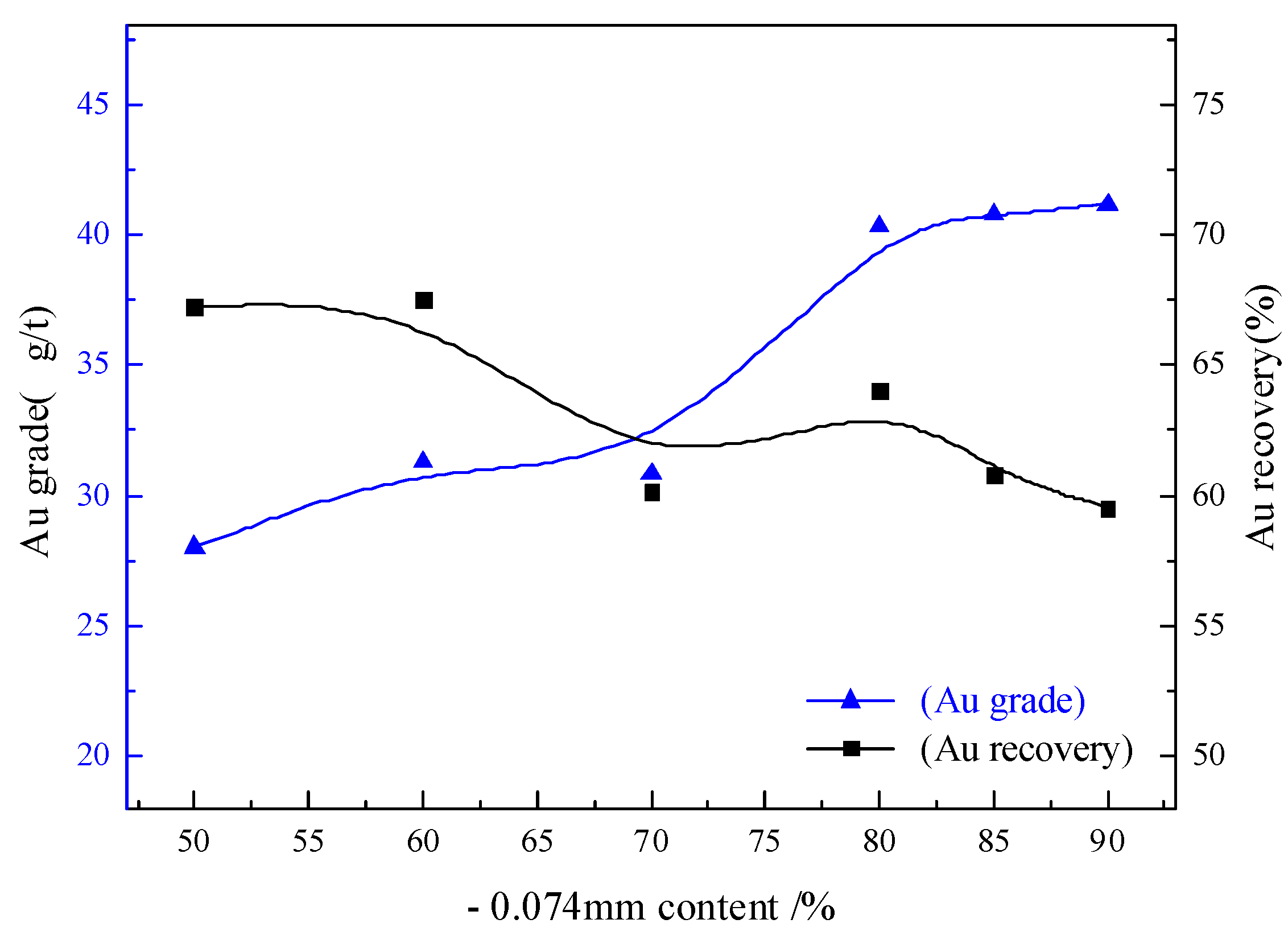

3.2.1. Grinding Fineness Condition Test

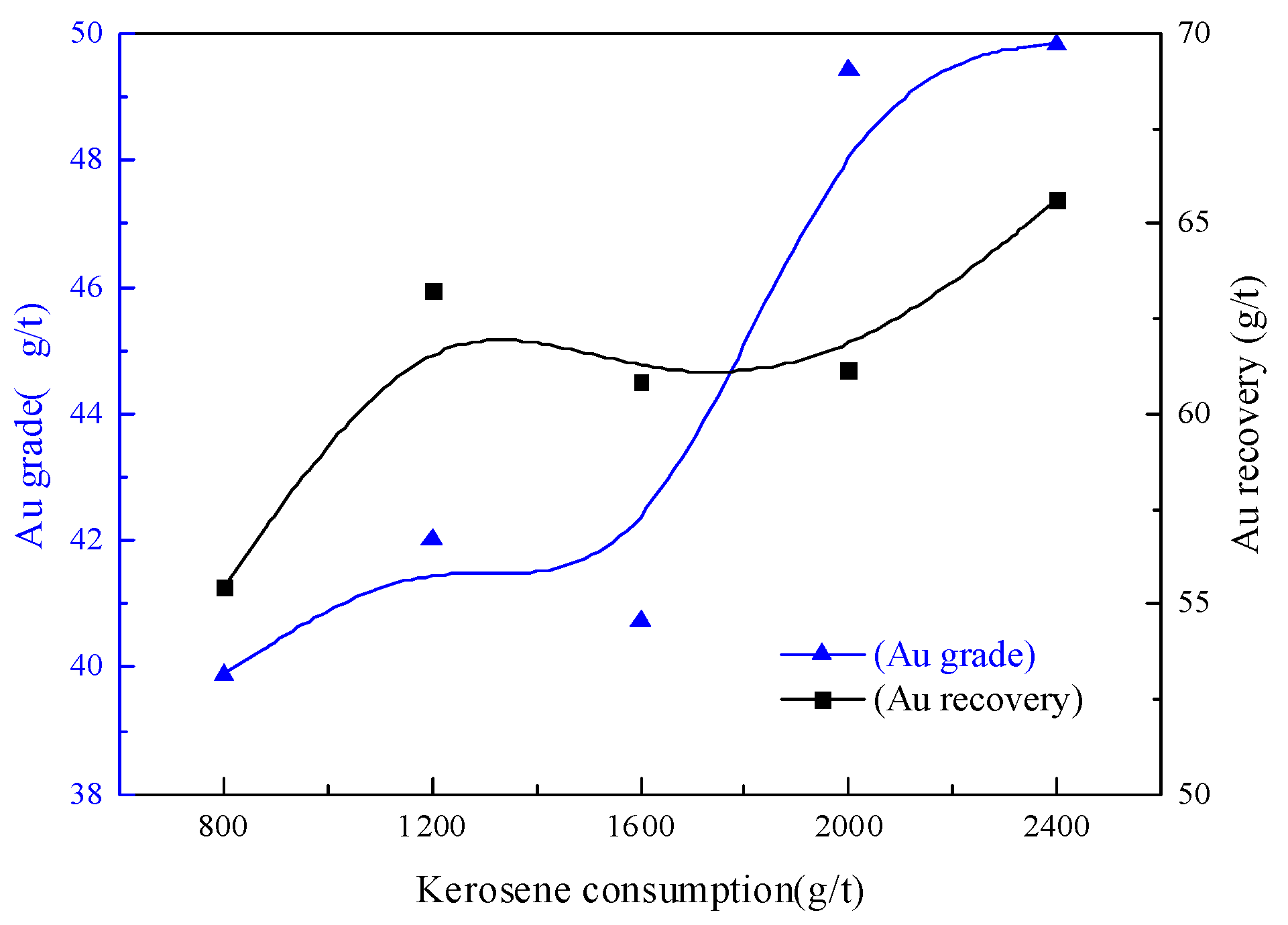

3.2.2. Kerosene Dosage Condition Test

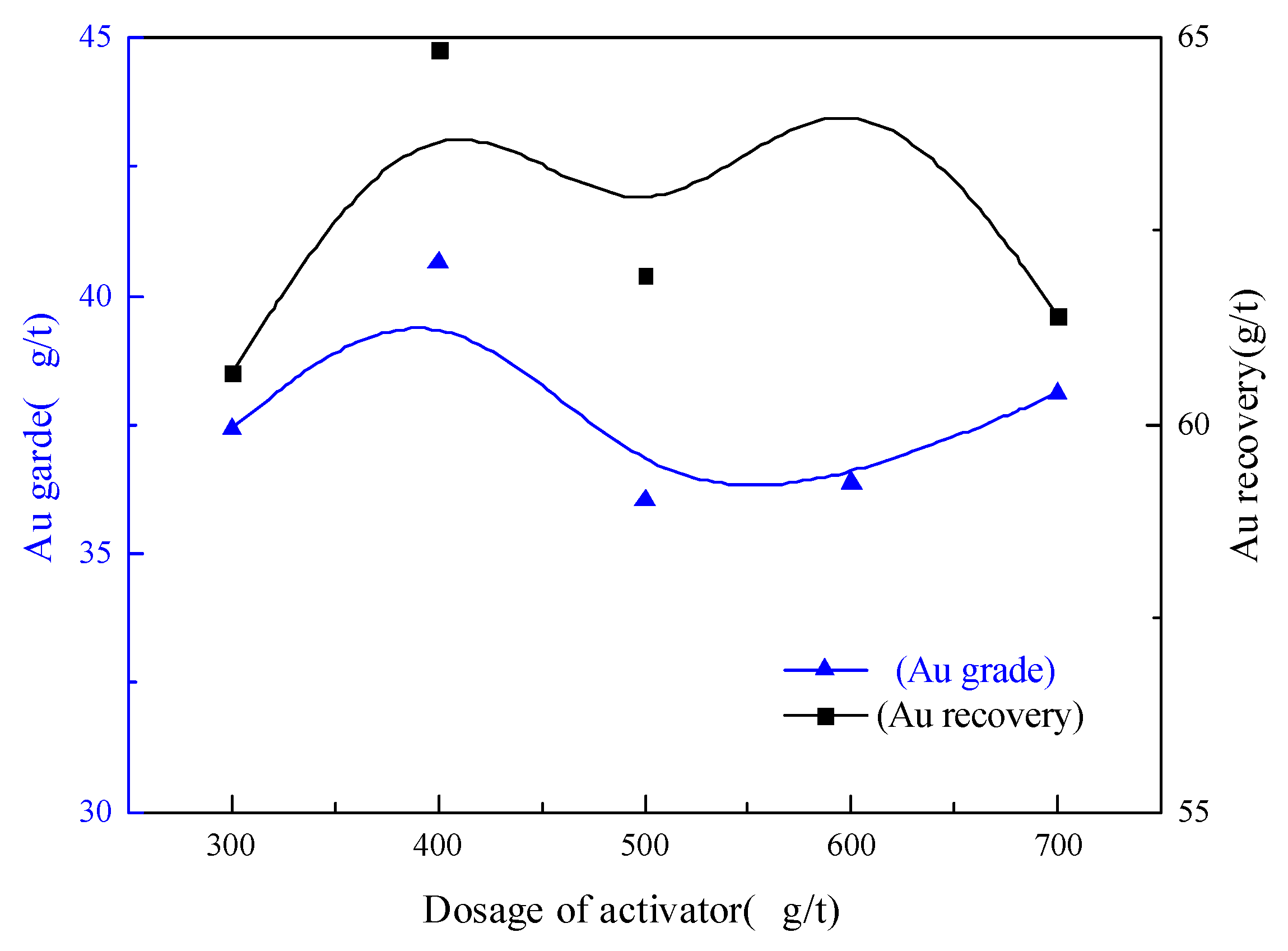

3.2.3. Activator Dosage Condition Test

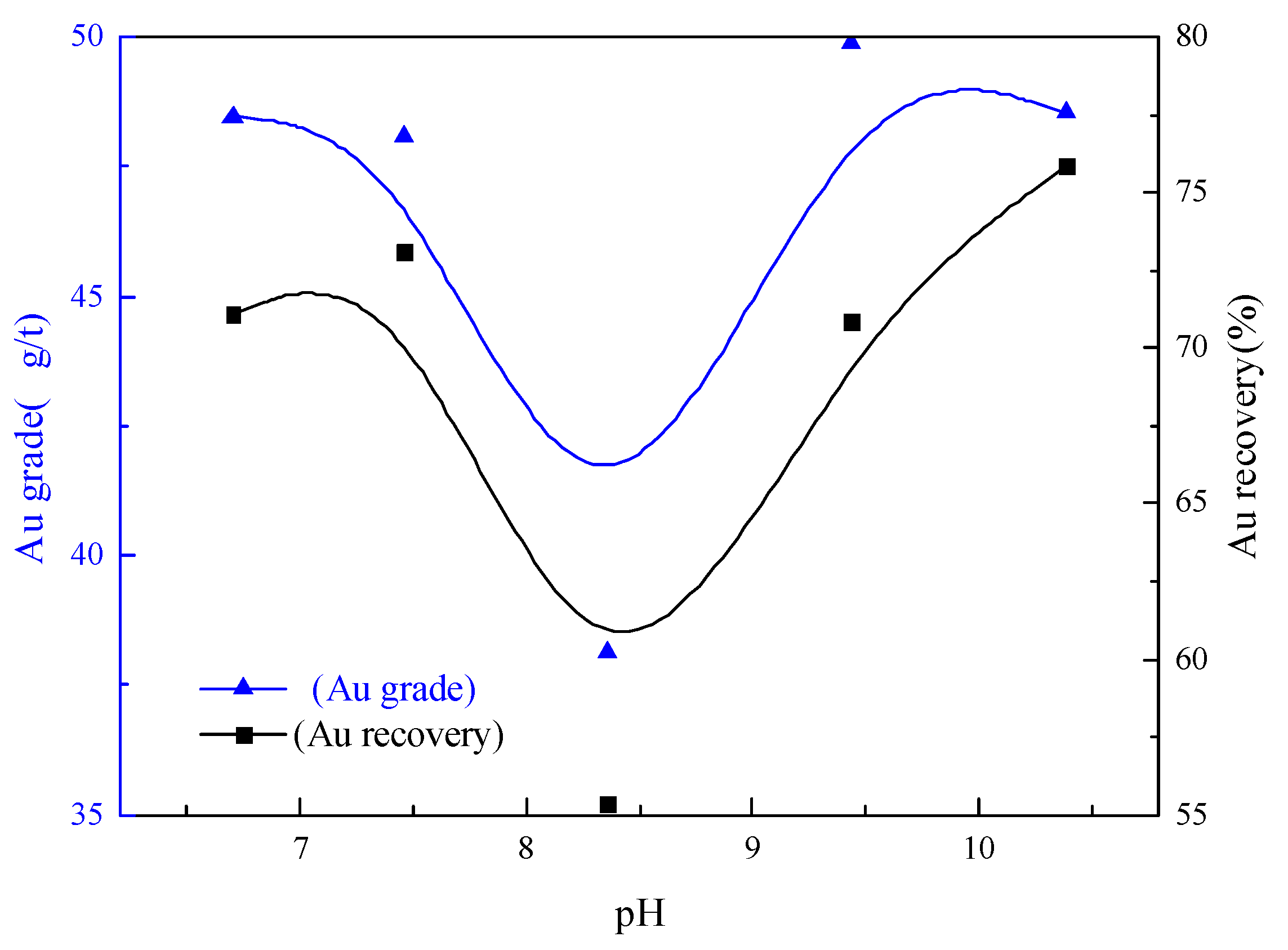

3.2.4. Pulp pH Condition Test

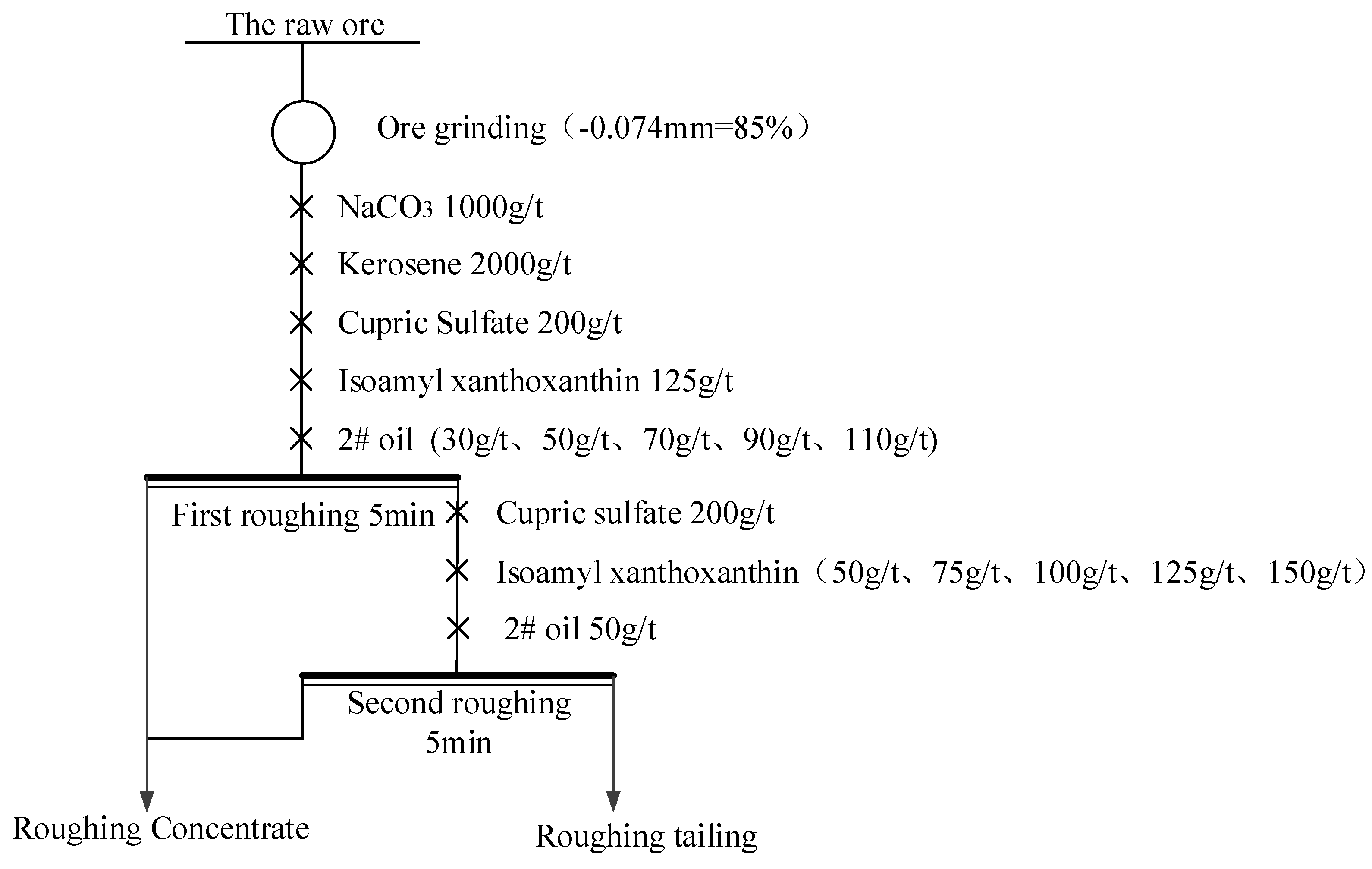

3.2.5. Collector Dosage Condition Test

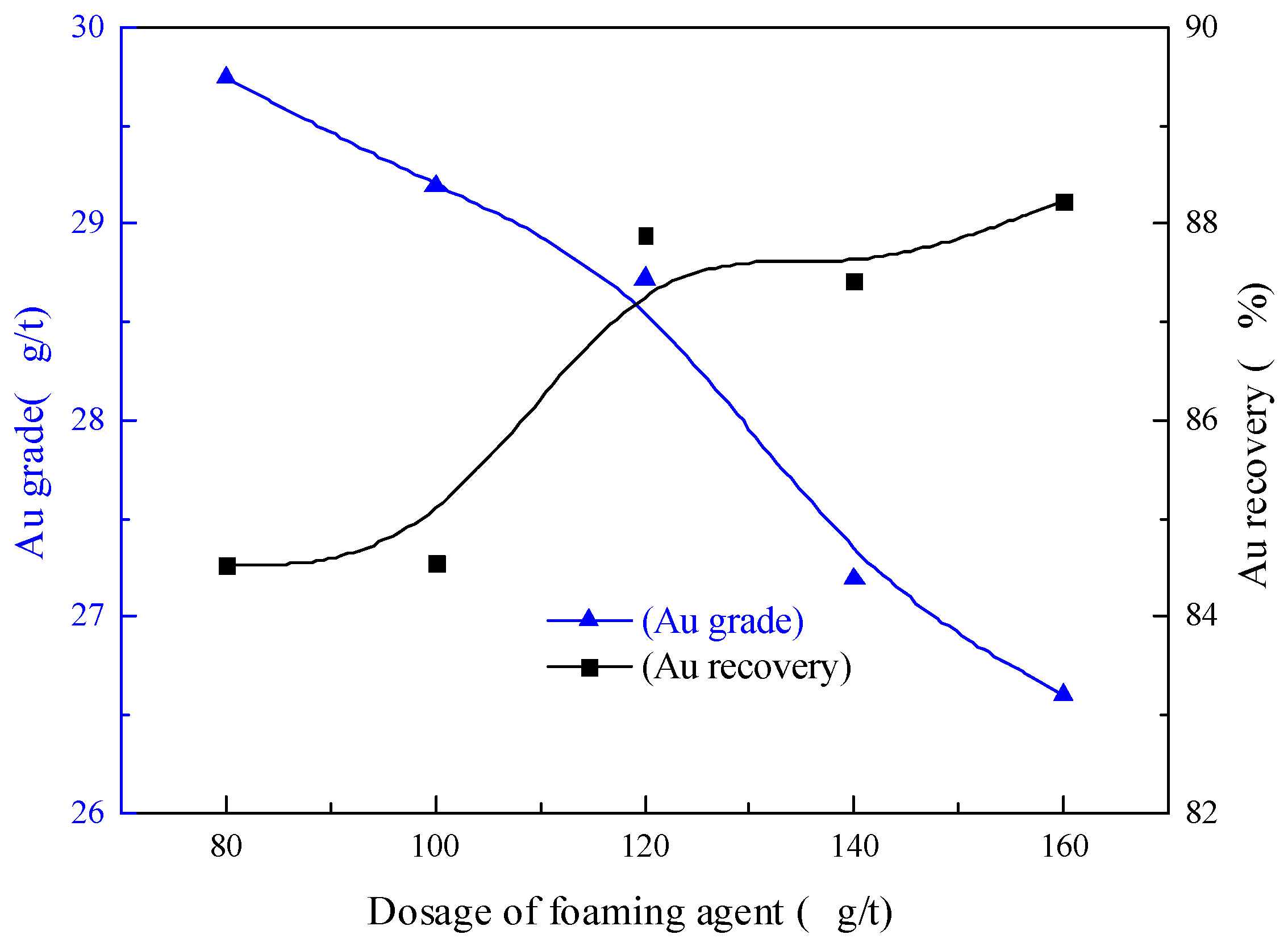

3.2.6. Foaming Agent Dosage Condition Test

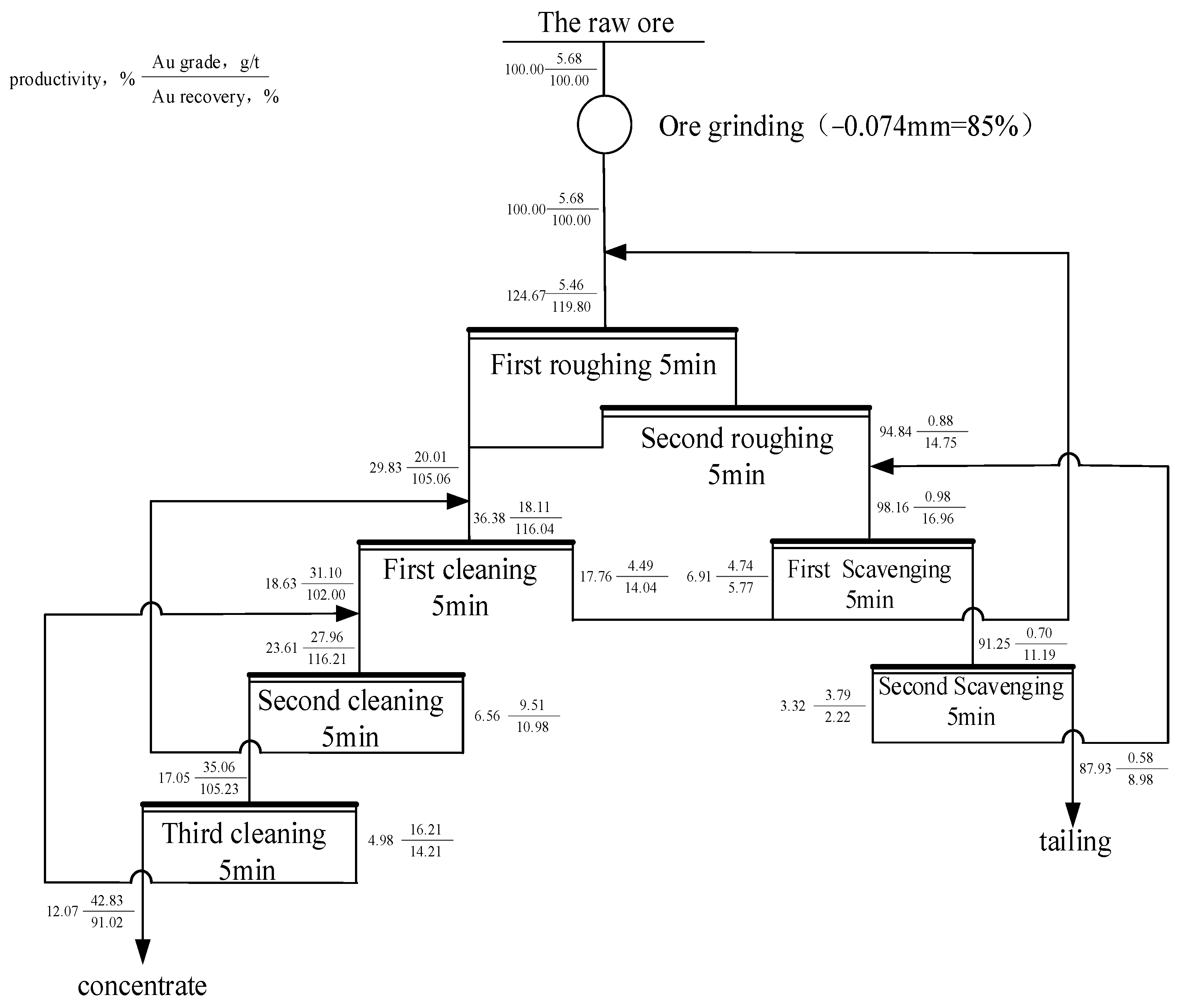

3.3. The Closed-Circuit Flotation Test

3.4. Property Analysis of Flotation Concentrate and Tailings

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The content of Au in the ore is 5.68 g/t, and the main minerals are quartz, muscovite, pyrite, and arsenopyrite, whose contents are 35.68%, 36.13%, 8.94%, and 1.05%, respectively. The gold ores are natural gold with a fine distribution and are mainly sulfide-coated gold, accounting for 79.46%. The main sulfide is pyrite, followed by arsenopyrite. The carbon content is 1.01%, and the main form is organic carbon.

- (2)

- The appropriate flotation process was determined as “two roughing, three cleaning and two scavenging”, and the reasonable grinding fineness were determined to be 85% of −0.074 mm. The flotation of the minerals was effectively separated using kerosene and collector flotation. The diversified utilization of kerosene was realized, which is of great significance for reducing mineral processing costs and ensuring environmental protection.

- (3)

- By using this experimental process, the concentrate with a Au grade of 42.83 g/t and recovery rate of 91.02% was obtained, and the contents of TFe and S were relatively high at 24.47% and 29.70%, respectively. In the final tailings, the Au grade was only 0.52 g/t, and the Ag content was <1 g/t; the TFe content was 2.62%. The contents of other metal elements, such As, S, and C, were low.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cao, P.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, Y.; Lai, S.; Liang, G.; Wang, X.; Tan, B. Identification of elements hindering gold leaching from gold-bearing dust and selection of gold extraction process. Hydrometallurgy 2021, 202, 105612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Rao, S.; Liu, W.; Zhang, D.; Chen, L. A selective process for extracting antimony from refractory gold ore. Hydrometallurgy 2017, 169, 571–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-H.; Zheng, Y.-J.; Cao, P.; Li, C.-H.; Lai, S.-Z.; Wang, X.-J. Process mineralogy characteristics of acid leaching residue produced in low-temperature roasting-acid leaching pretreatment process of refractory gold concentrates. Int. J. Miner. Met. Mater. 2018, 25, 1132–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, H.; Zhao, R.; Tong, L.; Chen, Q. Mineralogical characteristics and recovery process optimization analysis of a refractory gold ore with gold particles mainly encapsulated in pyrite and Arsenopyrite. Geochemistry 2023, 83, 125941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, F.; Du, J.; Peng, L.; Zhang, M.; Dong, Z.; Shen, Y.; Zhao, L. Selective and Effective Gold Recovery from Printed Circuit Boards and Gold Slag Using Amino-Acid-Functionalized Cellulose Microspheres. Polymers 2023, 15, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Kou, J.; Sun, C.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, H. A review of environmentally friendly gold lixiviants: Fundamentals, applications, and commonalities. Miner. Eng. 2023, 197, 108074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Natural Resources of China. China Mineral Resources Report; Geology Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2022; pp. 6–7.

- Ubaldini, S.; Vegliò, F.; Beolchini, F.; Toro, L.; Abbruzzese, C. Gold recovery from a refractory pyrrhotite ore by biooxidation. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2000, 60, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Feng, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, H.; Ju, J. Co-recovery of manganese from pyrolusite and gold from carbonaceous gold ore using fluidized roasting coupling technology. Chem. Eng. Process. Process. Intensif. 2020, 147, 107742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyke, B.; Johnston, R.; Brooks, P. The characterisation and behaviour of carbonaceous material in a refractory gold bearing ore. Miner. Eng. 1999, 12, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, R.; Ladeira, A. Reduction of preg-robbing activity of carbonaceous gold ores with the utilization of surface blinding additives. Miner. Eng. 2019, 131, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Pring, A. Mineral Transformations in Gold–(Silver) Tellurides in the Presence of Fluids: Nature and Experiment. Minerals 2019, 9, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreeva, E.D.; Matsueda, H.; Okrugin, V.M.; Takahashi, R.; Ono, S. Au–Ag–Te Mineralization of the Low-Sulfidation Epithermal Aginskoe Deposit, Central Kamchatka, Russia. Resour. Geol. 2013, 63, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Guo, X.-Y.; Tian, Q.-H.; Zhang, L. Recovery of gold from refractory gold ores: Effect of pyrite on the stability of the thiourea leaching system. Int. J. Miner. Met. Mater. 2021, 28, 956–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitando, O.; Senanayake, G.; Dai, X.; Breuer, P. The adsorption of gold(I) on minerals and activated carbon (preg-robbing) in non-ammoniacal thiosulfate solutions—Effect of calcium thiosulfate, silver(I), copper(I) and polythionate ions. Hydrometallurgy 2019, 184, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, A.M.; Ghahreman, A.; Bell, S. A comparative study of gold refractoriness by the application of QEMSCAN and diagnostic leach process. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2017, 169, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xiao, W.; Jin, J.; Han, Y. Oxidation Roasting of Fine-Grained Carbonaceous Gold Ore: The Effect of Aeration Rate. Minerals 2021, 11, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Han, Y.; Li, H.; Huai, Y.; Peng, Y.; Gu, X.; Yang, W. Mineral phase and structure changes during roasting of fine-grained carbonaceous gold ores and their effects on gold leaching efficiency. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2019, 27, 1184–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, T.; Yang, Y.; Xu, B.; He, Y. Improving gold recovery from a refractory ore via Na2SO4 assisted roasting and alkaline Na2S leaching. Hydrometallurgy 2019, 185, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilek, E.C.; Tuzci, G. Flotation behavior of native gold and gold-bearing sulfide minerals in a polymetallic gold ore. Part. Sci. Technol. 2022, 40, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.-J.; Liu, S.; Song, Y.-S.; Wen, J.-K.; Zhou, G.-Y.; Chen, Y. Comprehensive recovery of gold and base-metal sulfide minerals from a low-grade refractory ore. Int. J. Miner. Met. Mater. 2016, 23, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Gibson, C.; Borschneck, A.; Ghahreman, A. Transformer oil vs. kerosene: Selective collectors for C-matter flotation from a double refractory gold ore. Miner. Eng. 2023, 191, 107951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemppinen, J.; Aaltonen, A.; Sihvonen, T.; Leppinen, J.; Sirén, H. Xanthate degradation occurring in flotation process waters of a gold concentrator plant. Miner. Eng. 2015, 80, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monte, M.; Lins, F.; Oliveira, J. Selective flotation of gold from pyrite under oxidizing conditions. Int. J. Miner. Process. 1997, 51, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yoon, R.-H.; Morris, J. AFM surface force measurements conducted between gold surfaces treated in xanthate solutions. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2013, 122, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, R.; Hope, G.A.; Brown, G.M. Spectroelectrochemical investigations of the interaction of ethyl xanthate with copper, silver and gold: III. SERS of xanthate adsorbed on gold surfaces. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 1998, 137, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Gibson, C.E.; Ghahreman, A. The Separation of Carbonaceous Matter from Refractory Gold Ore Using Multi-Stage Flotation: A Case Study. Minerals 2021, 11, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, S.; Said, S.; El-Shahawi, M. Extraction and recovery of Au, Sb and Sn from electrorefined solid waste. Anal. Chim. Acta 2001, 436, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.-Q.; Monhemius, A.J.; Gochin, R.J. Relationship between attachment probability and surface energy in adhesion process of gold particles to oil-carbon agglomerates. J. Cent. South Univ. Technol. 2003, 10, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Peng, Y. The interaction of grinding media and collector in pyrite flotation at alkaline pH. Miner. Eng. 2020, 152, 106344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabieh, A.; Albijanic, B.; Eksteen, J. A review of the effects of grinding media and chemical conditions on the flotation of pyrite in refractory gold operations. Miner. Eng. 2016, 94, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, M.X.; Liu, Q. Oil-assisted flotation of fine hematite using sodium oleate or hydroxamic acids as a collector. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2018, 54, 1130–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, H.K.; Ström, G.; Karlstrom, K.; Schoelkopf, J.; Gane, P.A.C. Effect of excess dispersant on surface properties and liquid interactions on calcium carbonate containing coatings. Nord. Pulp Pap. Res. J. 2010, 25, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupka, N.; Rudolph, M. Role of sodium carbonate in scheelite flotation—A multi-faceted reagent. Miner. Eng. 2018, 129, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Gochin, R.; Monhemius, A. The adhesion of gold to oil–carbon agglomerates. Miner. Eng. 2004, 17, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Gochin, R.; Monhemius, A. Modelling gold particle adhesion to oil–carbon agglomerates. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2004, 74, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gredelj, S.; Zanin, M.; Grano, S. Selective flotation of carbon in the Pb–Zn carbonaceous sulphide ores of Century Mine, Zinifex. Miner. Eng. 2009, 22, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, W.S.; Wang, Q.; Chen, M. A review of Preg-robbing and the impact of chloride ions in the pressure oxidation of double refractory ores. Miner. Process. Extr. Met. Rev. 2022, 43, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Feng, D.; Lukey, G.C.; van Deventer, J.S.J. The behaviour of carbonaceous matter in cyanide leaching of gold. Hydrometallurgy 2005, 78, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.Q. Pretreatment and thiosulfate leaching of refractory gold-bearing arsenosulfide concentrates. J. Univ. Sci. Technol. Beijing 2005, 12, 385–389. [Google Scholar]

- Piervandi, Z. Pretreatment of refractory gold minerals by ozonation before the cyanidation process: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Mo, W.; Ma, S.; Yang, J.; Lin, M. Experimental Study on Microwave Pretreatment with Some Refractory Flotation Gold Concentrate; International Forum on Powder Technology & Application: Qingdao, China, 2011; pp. 71–75. [Google Scholar]

| Elements | Au (g/t) | Ag (g/t) | TFe | SiO2 | Al2O3 | CaO |

| Content/% | 5.68 | 8.76 | 5.08 | 58.28 | 14.51 | 2.22 |

| Elements | MgO | As | Pb | S | C | |

| Content/% | 2.35 | 0.364 | 0.011 | 3.90 | 1.02 |

| Nudity and Semi-Exposed Gold | Carbonate Coated Gold | Brown Iron Coated Gold | Sulphide Coated Gold | Silicate Coated Gold | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content/g × t−1 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 5.34 | 0.67 | 6.72 |

| Occupancy/% | 3.57 | 3.13 | 3.87 | 79.46 | 9.97 | 100.00 |

| Carbon in Carbonate | Organic Carbon | Graphite Carbon | Total Carbon | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content/% | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 5.34 |

| Occupancy/% | 3.57 | 3.13 | 3.87 | 79.46 |

| Elements | Au (g/t) | Ag (g/t) | TFe | S | C | As |

| Content/% | 42.83 | 71.70 | 24.47 | 29.70 | 3.0 | 2.72 |

| Elements | Au (g/t) | Ag (g/t) | TFe | S | C | As |

| Content/% | 0.58 | <1 | 2.62 | 0.117 | 0.797 | 0.031 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, X.; Yu, J.; Jin, J.; Sun, H.; Li, Y.; Han, Y. Using Kerosene as an Auxiliary Collector to Recover Gold from Refractory Gold Ore Based on Mineralogical Characteristics. Separations 2023, 10, 584. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations10120584

Sun X, Yu J, Jin J, Sun H, Li Y, Han Y. Using Kerosene as an Auxiliary Collector to Recover Gold from Refractory Gold Ore Based on Mineralogical Characteristics. Separations. 2023; 10(12):584. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations10120584

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Xuesong, Jianwen Yu, Jianping Jin, Hao Sun, Yanjun Li, and Yuexin Han. 2023. "Using Kerosene as an Auxiliary Collector to Recover Gold from Refractory Gold Ore Based on Mineralogical Characteristics" Separations 10, no. 12: 584. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations10120584

APA StyleSun, X., Yu, J., Jin, J., Sun, H., Li, Y., & Han, Y. (2023). Using Kerosene as an Auxiliary Collector to Recover Gold from Refractory Gold Ore Based on Mineralogical Characteristics. Separations, 10(12), 584. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations10120584