The Evaluation Gap in Astronomy—Explained through a Rational Choice Framework

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- The theory of Anomie

- Gaming

- Cognitive Dissonance

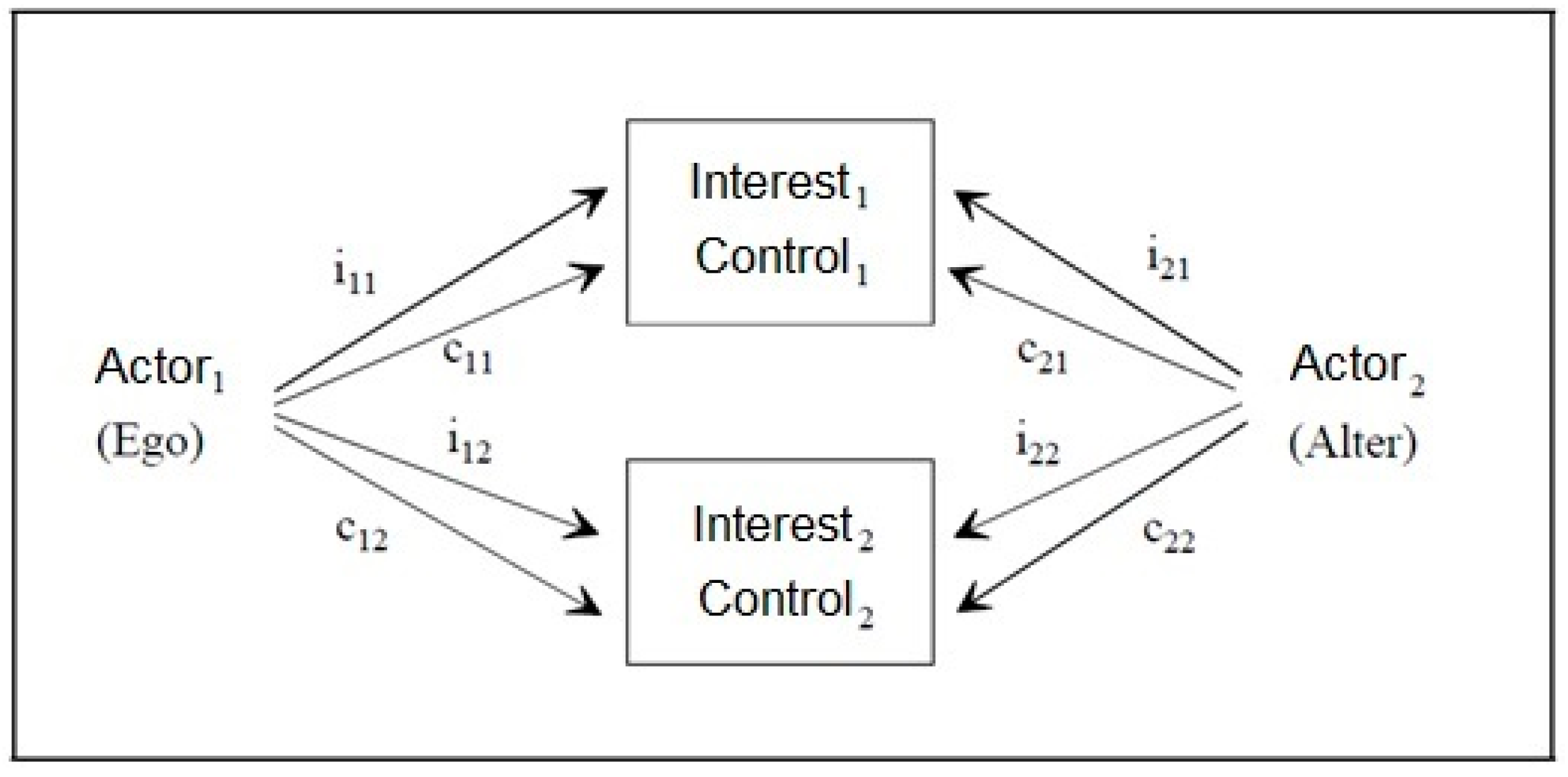

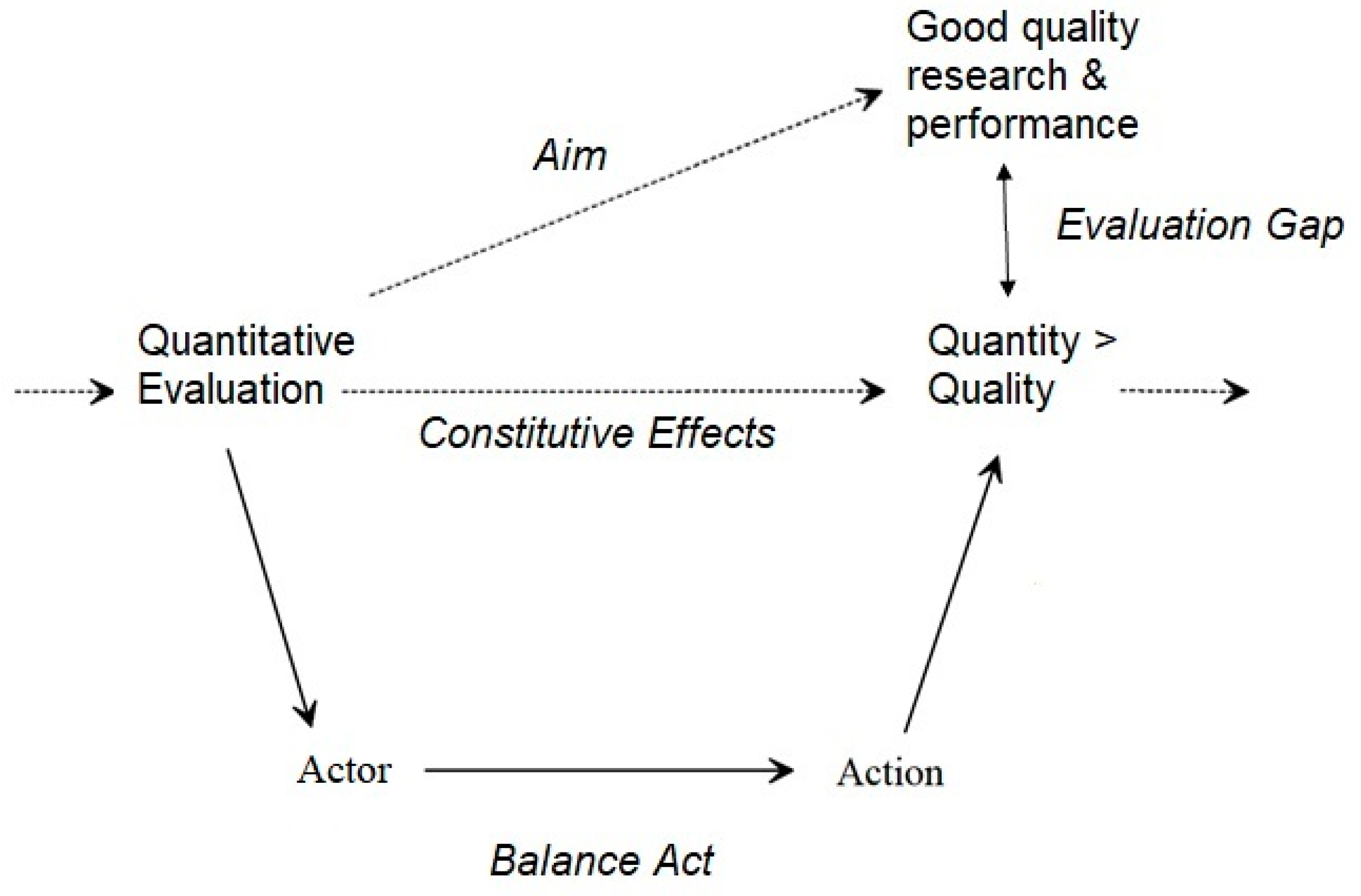

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Astronomer’s Research Behaviour

“Because it seems the only thing that is important is number of publications and so you have to do these if you want to continue.”[Int-PhD1]

3.1.1. Anomie

“So, I always look at data, to me that’s the key, on the other hand, frequently I find that my interpretation of data maybe different than other people but I [Coughing] try to give an honest interpretation but I always look for different ways of interpreting it. In science just like in culture there are norms. And I’m quite comfortable in keeping those norms as broad as possible.”

“We are in a society that we have to publish our results from different reasons. Yeah, to be visible as a scientist but also to share your science.”[Int-Postdoc1]

3.1.2. The Balancing Act

- The Indicator Game

“But astronomy really helps the day life.”, “We have to invent the day by day devices that are more efficient, that have …, that they use less power.”[Int-Faculty10]

“And usually the benefit is advance in science. You know politicians understand very easy issues, how to build a road to go from Milan to Rome. But if you say I build a telescope to understand the black hole they do not really understand very well.”[Int-Faculty10]

“I always refused playing any dirty games in contrast to a lot of other people I know and never pushed anyone else down. I raised everyone who worked with me up.”

“Because now what is happening, […] people are trying to game the system. So for example I know of people who work only to please four or five prominent people in the field. Who are their collaborators. So they just work like there’s—they are faculty members but they work like postdocs of those guys. […] Because they know that when the promotion case comes up they will the-they are going to be asked to write letters of recommendation and they’re going to say very nice things about you because you’ve just worked to please them. So I’ve not done that and I think I have suffered in my career due to delay in my promotions.”[Int-Faculty7]

“Yes, for what I know everyone has to publish, the more, the better position in the short list. (Yes, I see okay.) And that’s one aspect that I don’t like from researchers. […] because we are maybe it’s preferred to publish something that maybe you are not so very sure, or you are not so very confident about what you are saying but it seems that the most important thing is to publish not to do research.”[Int-PhD1]

“Sometimes you have to be opportunistic. Sometimes you have to go for easy publications that you can claim that you are successful, you are good, then you’ll get funding. And then you will finally have time to do what you want to do.”[Int-Faculty1]

“So with this comfort buffer [i.e., having many collaborators], the publications come out anyway. They tick all those boxes for the non-important people. So I can focus on what I want, what I think is important.”[Int-Faculty2]

“I wouldn’t conclude that you have to in order to succeed, succumb to such things as publish-or-perish. It’s relevant but it’s just as relevant you know, do you like to drive, well you still have to obey the speed limit that maybe a nuisance or you know stopping in a red light even though no one’s in the intersection I mean there’s certain compromises.”[Int-Faculty3]

- Dealing with the Tensions

“And to be successful they have to have more. I mean, fulfilling the minimum requirement never helps you getting into the real business. You have to be an over-performer, to be honest. So, that’s my advice to my students.”[Int-Faculty1]

“It is paper based, so it is quantity based and not quality based.”, “Then you have to do it quickly in that way, like everybody does and that is the problem.”

“And then so even though […] it doesn’t have a particularly high citation at all it doesn’t matter. I reckon-, I look at that and go, that was something which, you know, I came up with myself. And I had that, I had that, that, that fire within to, to pursue it. And that certainly happened about two or three other times in the papers where you’ve got that real sense of, no, this is something new and exciting and I’m learning stuff. And it’s not another run-of-the mill paper, which is good and publishable material, but it’s just another incremental advance.”[Int-Faculty8]

“I mean, I personally know that many researchers do not consider their most cited paper to be their best paper. I myself fall in the same loop. My best paper doesn’t have the largest number of citations. And funding agencies don’t care about lowly-cited papers. So, there is no clear answer how much, do they support this kind of high-quality research.”[Int-Faculty1]

“So yeah they were always like saying, yeah okay we’re not going to focus on publications only because it’s not a qualitative but only quantitative, that’s not the most important thing but in the end it was.”[Int-PhD2]

3.2. Resulting Collective Phenomenon

“And so even if you, fix it [i.e., introducing software citation] by encouraging citation counting, they haven’t fixed the attitudes of the people who are doing the evaluation. The people who are gatekeeping.”[Int-Journal; astronomer currently working for a journal]

“Okay. I mean, in the publishing process mostly it’s fine. You get used to what, you, you get used to what’s expected.”[Int-Faculty12]

“I’m sure that [sacrificing quality for quantity] happens a lot. Which is a bad thing as we all know, but since this is the world we are living in and this is still the system, although they were always saying like no we’re not going to look to number of papers, but they always did in the end so. Yeah we’re far from alternative ways of choosing people so.”[Int-PhD2]

3.2.1. Decreasing Research Quality

“But I want more than an apparent high quality paper. I want high quality research, high quality data.”, “Whereas I know at the back of my mind, for this data point I had to do something inconsistently with something other and okay even though the paper would appear high quality-. That should not be the goal, right? The goal should be that our research is high quality.”[Int-PhD3]

“The best quality I can. It’s not high quality but the best as I can. Okay everything is right [i.e., there are no errors].”[Int-PhD1]

“So, I fight hard to have quality over quantity as much as possible, but I often fail because of the pressure.”[Int-Faculty1]

“They take these [flashy] results but not the good things. […] So that’s the obsession with journal impact factors. We all know how little journal impact factors mean.”[Int-Faculty2]

“There are works that are very important and are published very quickly, and perhaps they are not quality works. There is a lot of publishing pressure. And sometimes the quality goes down because we have to publish like maniacs and because, you know, there is no written standard. But we all know that there must be standards.”, “This person has to publish quickly because maybe he or she needs to get more papers out to get a position. So, the quality goes down.”[Int-Postdoc2]

“No journal requires these things like they don’t require your codes, they don’t require that you actually give them step by step what you are doing. So I think as long as that doesn’t change as well so no change.”

“The only thing I guess the one negative aspect is the pressure on people to publish. And-and I think it’s not very healthy because we’re getting a lot more lower quality papers and it becomes harder because you have to read all those papers to find relevant information. So probably the pressure on publishing is not a good thing.”[Int-Postdoc3]

3.2.2. Biased Funding Decisions

“I think it leads to a lot of stove-piping in the field […]. To stay competitive, [what] all people can do is to continue to dig down deeper in their hole, in their discipline. Like they have to keep proposing for the thing they’re most expert on, instead of branching out into other areas. Like branching out has to happen on sort of other you know, side side projects or other funding. It’s very, it can be really difficult to get enough of a name for yourself in that area […] That’s not a good thing. That’s a- Yeah, and that’s a disadvantage of the field like that. I don’t think at this point it’s pretty diversified.”[Int-Faculty12]

3.2.3. Stress

“But it does seem like I do have to put in extra time as a lot of the scientists do. To get done what we need to and to stay competitive. […] And it could be difficult on relationships because I know for my husband he’s used to just working a normal workday, and so—Whereas for scientists it’s not just a job, it’s kind of a lifestyle.”

“I mean, I’ve had several friends of mine going to the States and, yeah, then go for tenure, but not succeeding. And it’s just, doesn’t sound like a very pleasant to them, I’ll say so.”

“So, you really didn’t like what you heard and you feel personally attacked, you know. And it’s kind of it takes a while to get over that. And it certainly as a young researcher, when you see your first referee report of that type, it can be extraordinarily dispiriting and you need to have a good supervisor who says ‘Don’t worry, this is quite common. Referees will often attack weak points, but that’s part of the scientific process.’ […] And this could have quite a negative effect on people who are trying to start off in the field and who go like, ‘Well, he hates me. I’m useless.’”[Int-Faculty8]

3.2.4. The Evaluation Gap in Astronomy

“If I can predict the outcome, it’s not science. And several times I’ve made the right choice to take some risk and just to explore. That’s how you find new things.”[Int-Faculty2]

“I basically want to do research where people can base-. There’s this saying like, ‘I was standing on the shoulders of giants.’ Basically that’s what I want. I hope research would be that you could easily build on previous works. Where you can-. At the moment people just trying to do the same stuff because other people haven’t made available their way of methods or codes, and they have to make it up all over again. And then you’re only incrementally enhancing the field, and you should really be- […] And to make something even bigger which later on, in ten years becomes yet again, becomes trivial, and you can build something more. I’m basically seeing it as standing on the shoulders and making a pyramid of knowledge.”[Int-PhD3]

“But then there’s the frustration of well, you know I’m writing this journal article […] not just to tell a story or to, to improve [knowledge]. But I’m also doing it to advance my career. And so that ends up being like a [bottleneck] on that sharing, right? It ends up being, you know, ‘I don’t want to share this material because I have to then write another paper on it’. And which might have some legitimacy or might have more if you said something like, have a student who needs to finish the PhD. And so they need to […] to safely finish their project. […] And so then the journals become, feel like-, or at least feel like—I don’t know if the journals do—but I feel like that the prioritization is about helping people to publish papers rather than having people to participate in this, this networking of resources. And so, when we talk about that inconsistent loop, you know it might be useful if people got credit for the releasing of data, rather than for the writing of papers.”[Int-Journal]

“It’s not valid to assume that the scientific community wouldn’t want to serve the societal benefits. Think about why people are doing it. If researchers in universities were in for the money,—come on, they would better do something else, it’s definitely not the best way to become rich. So they want to achieve something,—why do they want to achieve this? Don’t they want to make some difference in this world? So isn’t that a societal benefit? They want to make the whole process as efficient as possible. The general interests of a lot of researchers are much aligned to the genuine public interests. Why then do we have a system that is completely offset on this? It not only doesn’t make sense, it’s also very inefficient. You know, we’re publishing more and more and more, the quality doesn’t get better, and the quality standards drop in my opinion. We have an inflationary system because we attach larger and larger numbers of research excellence to it, it doesn’t mean anything.—It’s becoming worse and worse year by year.”[Int-Faculty2]

4. Discussion

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Label | Gender | Age | Country of Employment | Date of Interview | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | <35 | 35–60 | >60 | Global North | Global South | ||

| Int-Faculty1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 27 June 2017 |

| Int-PhD1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 27 June 2017 |

| Int-PhD2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 28 June 2017 |

| Int-Faculty2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 28 June 2017 |

| Int-PhD3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 29 June 2017 |

| Int-Journal | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 27 August 2018 |

| Int-Faculty3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 27 August 2018 |

| Int-Faculty4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 28 August 2018 |

| Int-Faculty5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 29 August 2018 |

| Int-Faculty6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 29 August 2018 |

| Int-Faculty7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 29 August 2018 |

| Int-Faculty8 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 October 2018 |

| Int-Faculty9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 26 October 2018 |

| Int-Postdoc1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 9 November 2018 |

| Int-Faculty10 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 9 November 2018 |

| Int-Faculty11 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 21 November 2018 |

| Int-Postdoc2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 December 2018 |

| Int-Faculty12 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 December 2018 |

| Int-Postdoc3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 December 2018 |

| Sample total | 5 | 14 | 3 | 12 | 4 | 16 | 3 | |

| Sample in percent | 26% | 74% | 16% | 63% | 21% | 84% | 16% | |

| Field 5 in percent | 18% | 82% | 4% | 57% | 39% | 80% | 20% | |

Appendix B

| Code | Memo |

|---|---|

| Authorship | Mentioning of the relevance of authorship (includes also order of authorship) |

| CAREER Clarity/Expectations | Mentions of how aware one was of the expectations that come with one’s aspired career in academia and how consciously one chose a career in academia |

| Collaboration | Mentioning of the importance and practice of collaborations |

| Competition | Mentioning of the importance and practice of competition |

| Curiosity | When curiosity is mentioned as a reason for doing research (e.g., “Wanting to understand”) |

| >Puzzle | Curiosity may express itself through a variety of other forms. One of which is the love for “Puzzle solving” [43] When a reason for doing research involves love for puzzle solving (e.g., “intellectual challenge”) |

| Epistemic Subculture | Mentioning of relevance of the topic of research, and whether one works rather in Instrumentation/Observation/Theory |

| Failure | Mentioning of the meaning of failure (e.g., to publish, to obtain research results, to take the next career step) to the interviewee |

| Funding | Mentioning of the importance/practice of receiving funding |

| Gaming | Mentioning of any kind of gaming strategy, targeting, capacity of convincing funders/politicians to invest in one’s research (e.g., “Sales men”), salami slicing, etc |

| Impact | Mentioning of the relevance/meaning of one’s research to have “impact” |

| Indicator | Mention of all sorts of indicators (publication rates, H-index etc) |

| >Awareness | How much do astronomers themselves reflect on being measured? |

| Integrity | Mentioning of encouragement or threat to research integrity. I.e. also use for opposite like: Fraud, Fake, Cheat |

| Limitations/Obstacles | Mentioning of all sorts of things that may be restricting for conducting research (e.g., time, resources, staff, etc) |

| Luck | Mentioning of the role of luck as opposed to merit in receiving funding/positions etc |

| Matthew effect | Mentioning of the Matthew Effect phenomenon; Incidences where resources (e.g., funding) were more dependent on prestige/quantitative output than the quality of the research; Situations where past output determines future success; Also mentioned as “the chicken or egg problem” by an interviewee in Heuritsch [2]: funding is difficult without having acquired acknowledgement for previous research and acquiring such acknowledgement is difficult without funding in order to perform research. |

| Negative results | Mentioning of the relevance/publishability of negative results, incl. non-detections |

| Output orientation | Displaying need to pay attention to output. E.g. when certain output is mentioned as a basis of one’s assessment. Including perceived expectations on one’s output. |

| >Citation rates | Mentioning of the relevance of citation rate |

| >Publication rates | Mentioning of the relevance of publication rate |

| Politics | Mentioning of the importance of political aspects of hiring/how the research is organised |

| Pressure | Perceiving any kind of pressure (e.g., to publish/to receive funding) |

| Prestige | Mentioning of the relevance of prestige/being known in the community |

| Publication | Mentioning of the importance/practice of publishing |

| Purple | Interviewee expressions that are particularly demonstrative/well expressed so that they can be used well for citing in the resulting paper. |

| Quality | Mentioning of the relevance of research quality and effects on research quality |

| >3 criteria | If at least one of the 3 criteria that Heuritsch [2] identified as the astronomer’s most important quality criteria is mentioned |

| Replicability | Mentioning of relevance of replicability and also practice of ensuring replicability |

| Riskiness | Mentioning of the relevance and practice of taking risks in research |

| Sexy topics | Mentioning of relevance of so-called sexy/fashionable/flashy topics |

| Uncertainty (career) | Expressions of uncertainty and associated (negative) feelings about one’s career in academia |

| Temporality | When time(ing) is important |

Appendix C

| Concept | Research Theme | Question # | Interview Question |

|---|---|---|---|

| Introduction Introduction | Background | 1 | Please tell me about your background—from how you decided to go into Astronomy to how you got into your current position. |

| Astronomy | 2 | What is special about astronomy for you? | |

| Evaluation | Necessary conditions to perform science | 3 | What do you need to do to be able to do your research? |

| Evaluation | 3.10 | >What processes are involved in your research/What resources do you need?/What obstacles do you face in the process? | |

| Data | Challenges of the data acquisition process | 4 | Do you search for published data (do you use data of others?) |

| Data | 5 | What are the challenges in getting the data you need? | |

| Data | 5.10 | >Telescope | |

| Data | 5.20 | >Database | |

| Data | Value/Importance of data regardless of publishable results | 6.00 | Have you cited data? |

| Data | 7.00 | Do you usually publish data with your research results? | |

| Data | 7.10 | >Do you publish data separately? | |

| Data | 7.20 | >Do you think this happens often in your discipline? | |

| Evaluation | Practices: Publishing | 8.00 | What are the criteria to publish your work? |

| Evaluation | 8.10 | >Can you tell me a few examples of your successes and disappointments regarding publishing? | |

| Evaluation | Practices: Funding | 9.00 | What are the criteria to receive funding? |

| Evaluation | Practices: Funding | 10.00 | Do you find funding decisions fair/reasonable? |

| Evaluation | Practices: Funding | 11.00 | Can you tell me a few examples of your successes and disappointments regarding acquiring funding? |

| Evaluation | Other experiences with evaluation | 12.00 | You told me about about postition, getting money etc –are there any aspects of your scientific work where assessment plays a role? |

| Evaluation | 12.10 | >In what way do you face situations in which your work or parts of what you do is appraised directly or indirectly by others? (e.g., Yearly appraisals with your supervisor/Peer review for funding applications/Mid-term reviews for projects) | |

| Evaluation | 12.20 | >What role do indicators play in assessments? | |

| Evaluation | Temporality | 13.00 | If you were starting your career now how would things be different for you? |

| Notions of quality | Introduction to this block | 14.00 | Well, thank you for telling me about your research interests and activities. In this last section of the interview I’d like to ask a few questions about ideas of ‘quality’ in scientific work. Sometimes people talk about ‘quality’ in research or in publications, and I’d be interested to know how you think about it. Perhaps I could start with the question—what, in your view, makes a good scientific paper |

| Notions of quality | What is research quality for the astronomer? | 15.00 | Would you say ‘quality’ is something you judge when reading a paper? |

| 15.10 | >What makes a good paper in your opinion? | ||

| Notions of quality | 15.20 | >When you read a paper, how do you decide if it is a good article? | |

| Notions of quality | 16.00 | Could you give me an example of a “high quality” work? | |

| Notions of quality | What is quality for “the system”? | 16.10 | >How was this work perceived by your peers/the community? |

| Notions of quality | Divergent notions of quality? | 17.00 | What is your highest quality paper? |

| Notions of quality | 17.10 | >Do you think it was the most important one? | |

| Notions of quality | 17.11 | >>Was it the most influential one? | |

| Notions of quality | 17.20 | >Does it have most citations? | |

| Notions of quality | 17.30 | >(If no:): how would you describe the difference (e.g., between a paper that is good and a paper that has the most citations)? | |

| Evaluation inquiry | Ideas for alternative evaluation/indicators? | 18.00 | What would you wish that would be measured? |

| Notions of quality | What is quality for “the system”? | 19.00 | What makes a good application/funding proposal? |

| Evaluation inquiry | Ideas for alternative evaluation/indicators? | 18.00 | What would you wish that would be measured? |

| 1 | Note here that Bourdieu’s [22] concept of capital and Esser’s concept of “control of resources” refer essentially the same phenomenon: An actor has or has not access to various forms or capital (resources), such as money, time, social network and has incorporated certain knowledge and values. |

| 2 | “I mean so that’s how you do good science you just look at your data. […] What the data are telling you. “ [Int-Faculty2] |

| 3 | “Yeah so we’re back to the thing. Is this the true academic quality? I mean the true academy hasn’t changed. Quality is quality. Or what people would call quality. Or people, mistake quantity for quality. Any metric measures quantity, it doesn’t measure quality.” [Int-Faculty2] |

| 4 | |

| 5 | https://www.iau.org/administration/membership/individual/distribution/ (accessed on 17 May 2023). |

References

- Fochler, M.; De Rijcke, S. Implicated in the Indicator Game? An Experimental Debate. Engag. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2017, 3, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heuritsch, J. Effects of metrics in research evaluation on knowledge production in astronomy: A case study on Evaluation Gap and Constitutive Effects. In Proceedings of the STS Conference, Graz, Austria, 6–7 May 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, T. Trust in Numbers; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Desrosières, A. The Politics of Large Numbers—A History of Statistical Reasoning; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998; ISBN 9780674009691. [Google Scholar]

- Espeland, W.N.; Stevens, M.L. A Sociology of Quantification. Eur. J. Sociol. 2008, 49, 401–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wouters, P. Bridging the Evaluation Gap. Engag. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2017, 3, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Laudel, G.; Gläser, J. Beyond breakthrough research: Epistemic properties of research and their consequences for research funding. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1204–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushforth, A.D.; De Rijcke, S. Accounting for Impact? Minerva 2015, 53, 117–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dahler-Larsen, P. Constitutive Effects of Performance Indicators: Getting beyond unintended consequences. Public Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 969–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuritsch, J. The Structural Conditions for the Evaluation Gap in Astronomy. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.03068. [Google Scholar]

- Devoust, E.; Schmadel, L.D. A study of the publishing activity of astronomers since 1969. Scientometrics 1991, 22, 9–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, M.J.; Henneken, E.A. Measuring Metrics—A 40-Year Longitudinal Cross-Validation of Citations, Downloads, and Peer Review in Astrophysics. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2017, 68, 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCray, W.P. Large Telescopes and the Moral Economy of Recent astronomy. Soc. Stud. Sci. 2000, 30, 685–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson-Grosjean, J.; Fairley, C. Moral Economies in Science: From Ideal to Pragmatic. Minerva 2009, 47, 147–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baneke, D. Let’s Not Talk About Science: The Normalization of Big Science and the Moral Economy of Modern astronomy. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2020, 45, 164–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E.P. The moral economy of the English crowd in the 18th century. In Customs in Common: Studies in Traditional Popular Culture; Thompson, E.P., Ed.; New Press/W.W. Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 185–258. [Google Scholar]

- Kohler, R.E. Moral economy, material culture and community in drosophila genetics. In The Science Studies Reader; Biagioli, M., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 243–257. [Google Scholar]

- Merton, R.K. Science and the social order. Philos. Sci. 1938, 5, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, H. Soziologie. Spezielle Grundlagen. Band 1: Situationslogik und Handeln; Campus Verlag: Frankfurt, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Esser, H. Soziologie. Spezielle Grundlagen. Band 5: Institutionen; Campus Verlag: Frankfurt, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R.K. Social Theory and Social Structure. Toward the Codification of Theory and Research; Free Press: Glencoe, IL, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Ökonomisches Kapital, kulturelles Kapital, soziales Kapital. In Soziale Ungleichheiten; Kreckel, R., Ed.; Sonderband 2 der Sozialen Welt: Göttingen, Germany, 1983; p. 185ff. [Google Scholar]

- Esser, H. Soziologie. Spezielle Grundlagen. Band 3: Soziales Handeln; Campus Verlag: Frankfurt, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis; SAGE Publication: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Merton, R.K. The Matthew effect in science. Science 1968, 159, 56–63, Page references are to the version reprinted in Merton (1973). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taubert, N. Fremde Galaxien und Abstrakte Welten: Open Access in Astronomie und Mathematik. Soziologische Perspektiven; Transcript Science Studies; transcript Verlag: Bielefeld, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Merton, R.K. Priorities in Scientific Discovery. In The Sociology of Science. Theoretical and Empirical Investigations; Storer, N.W., Ed.; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA; London, UK, 1973; pp. 286–324. [Google Scholar]

- Gagné, M.; Forest, J.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Crevier-Braud, L.; van den Broeck, A.; Aspeli, A.K.; Bellerose, J.; Benabou, C.; Chemolli, E.; Güntert, S.T.; et al. The Multidimensional Work Motivation Scale: Validation evidence in seven languages and nine countries. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2015, 24, 178–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, B. Hyperauthorship: A Postmodern Perversion or Evidence of a Structural Shiftin Scholarly Communication Practices? J. Am. Soc. Sci. Technol. 2001, 52, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluchino, A.; Biondo, A.E.; Rapisarda, A. Talent vs Luck: The role of randomness in success and failure. Adv. Complex Syst. 2018, 21, 1850014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, J.R.; Mountain, M. The Evolving Sociology of Ground-Based Optical and Infrared astronomy at the Start of the 21st Century. In Organizations and Strategies in Astronomy; Heck, A., Ed.; Astrophysics and Space Science Library; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 6, pp. 11–37. [Google Scholar]

- Heidler, R. Epistemic Cultures in Conflict: The Case of astronomy and High Energy Physics. Minerva 2017, 55, 249–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broad, W.J. The Publishing Game: Getting More for Less. Science 1981, 211, 1137–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anderl, S. Astronomy and Astrophysics. In The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy of Science; Humphreys, P., Ed.; Oxford Handbooks: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zuiderwijk, A.; Spiers, H. Sharing and re-using open data: A case study of motivations in astrophysics. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 49, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patat, F.; Boffin, H.M.J.; Bordelon, D.; Grothkopf, U.; Meakins, S.; Mieske, S.; Rejkuba, M. The ESO Survey of Non-Publishing Programmes. Eur. South. Obs. 2017, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, D.B. Astronomy in the twentieth century. Scientometries 1986, 9, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waaijer, C.J.F.; Teelken, C.; Wouters, P.F.; van der Weijden, I.C.M. Competition in Science: Links Between Publication Pressure, Grant Pressure and the Academic Job Market. High Educ. Policy 2017, 31, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruocco, G.; Dario, C.; Folli, V.; Leonetti, M. Bibliometric indicators: The origin of their log-normal distribution and why they are not a reliable proxy for an individual scholar’s talent. Palgrave Commun. 2017, 3, 17064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thurner, S.; Liu, W.; Klimek, P.; Cheong, S.A. The role of mainstreamness and interdisciplinary for the relevance of scientific papers. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.S. Foundations of Social Theory; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Heuritsch, J. Knowledge Utilization and Open Science Policies: Noble aims that ensure quality research or Ordering discoveries like a pizza? published at the International Astronautical Federation Congress 2019. arXiv 2019, arXiv:2005.14021. Available online: https://iafastro.directory/iac/paper/id/50665/summary/ (accessed on 17 May 2023).

- Stephan, P. How Economics Shapes Science; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Heuritsch, J. The Evaluation Gap in Astronomy—Explained through a Rational Choice Framework. Publications 2023, 11, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications11020033

Heuritsch J. The Evaluation Gap in Astronomy—Explained through a Rational Choice Framework. Publications. 2023; 11(2):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications11020033

Chicago/Turabian StyleHeuritsch, Julia. 2023. "The Evaluation Gap in Astronomy—Explained through a Rational Choice Framework" Publications 11, no. 2: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications11020033

APA StyleHeuritsch, J. (2023). The Evaluation Gap in Astronomy—Explained through a Rational Choice Framework. Publications, 11(2), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications11020033