Beyond Keywords: Effective Strategies for Building Consistent Reference Lists in Scientific Research

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

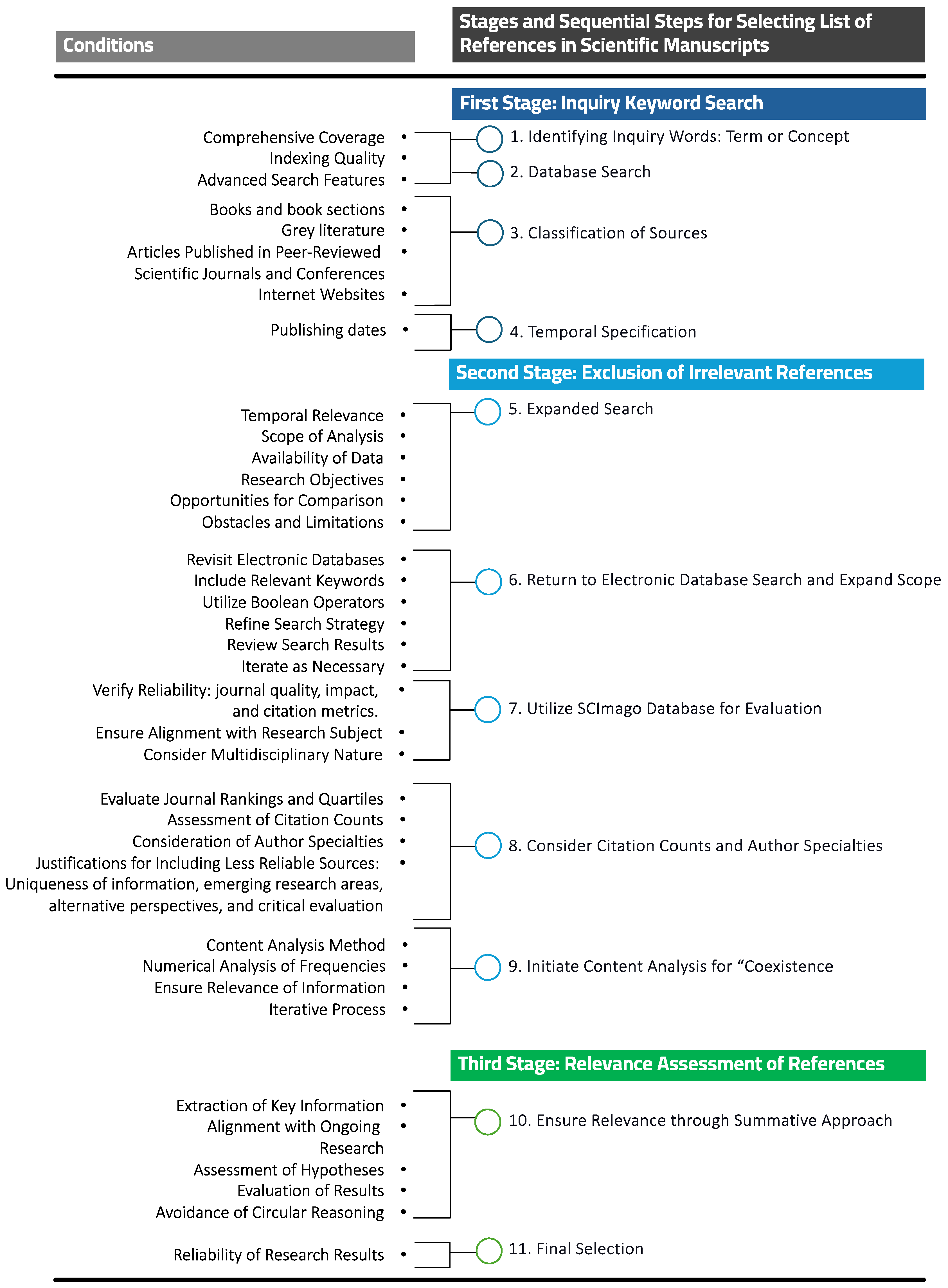

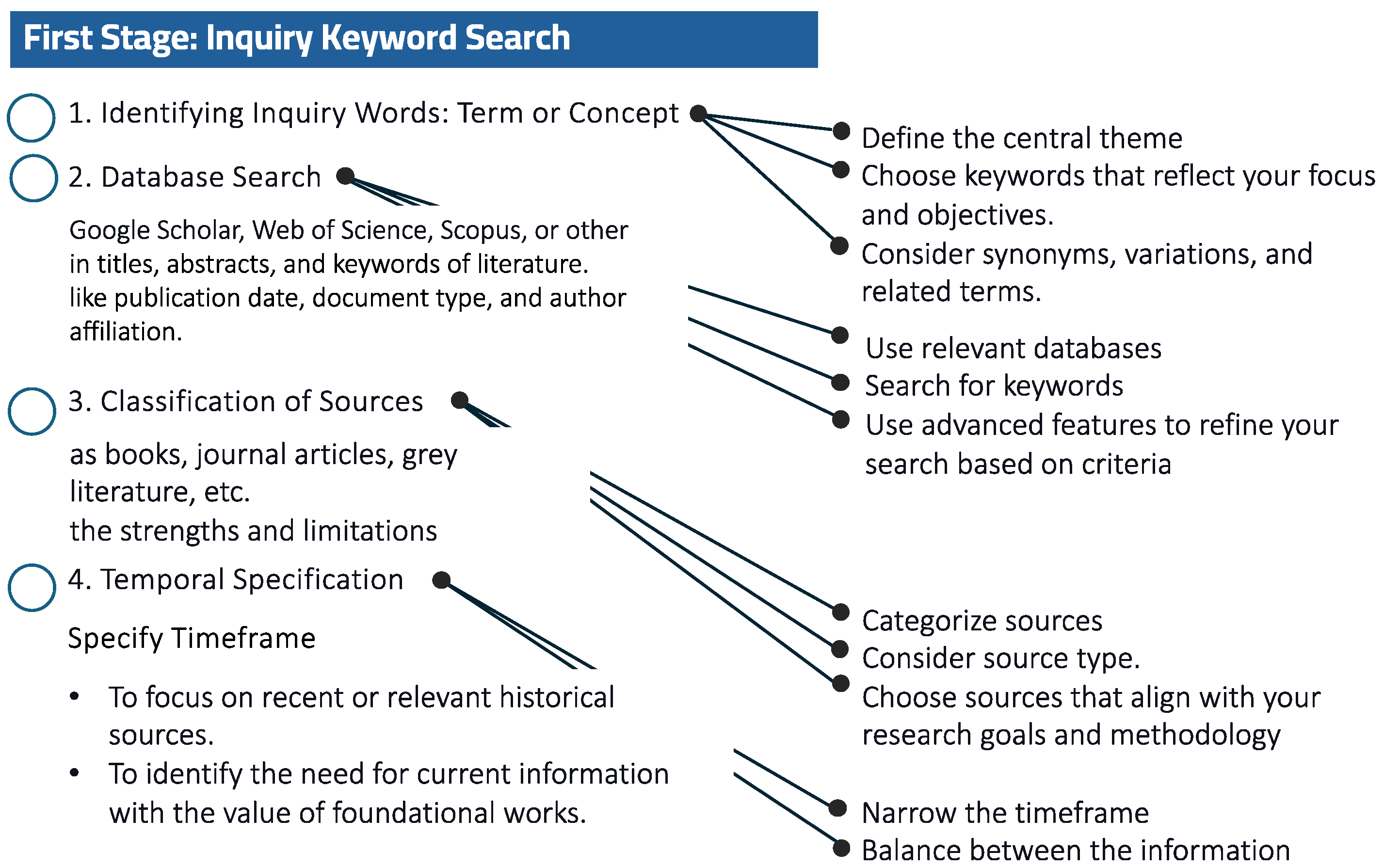

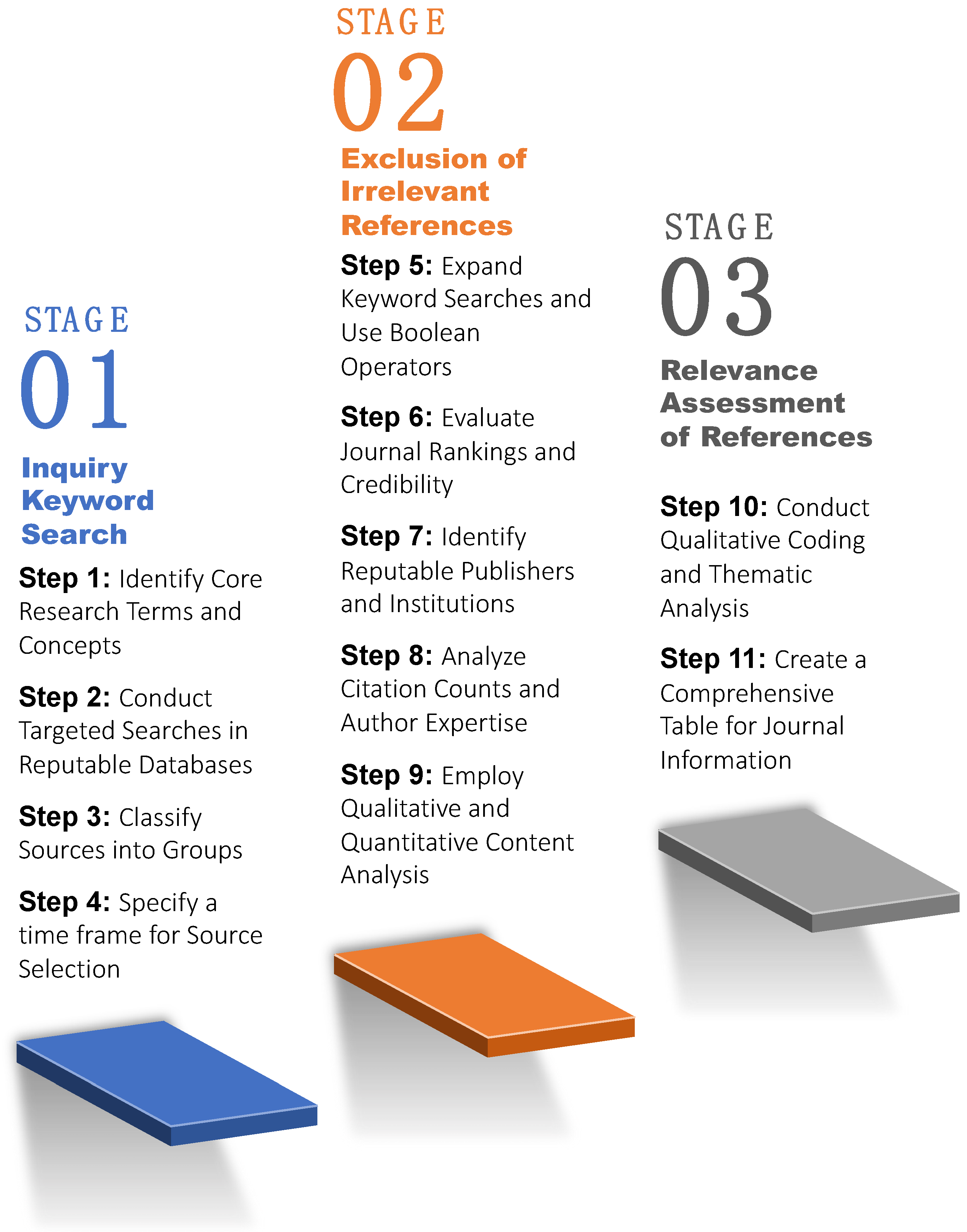

3.1. First Stage: Inquiry Keyword Search

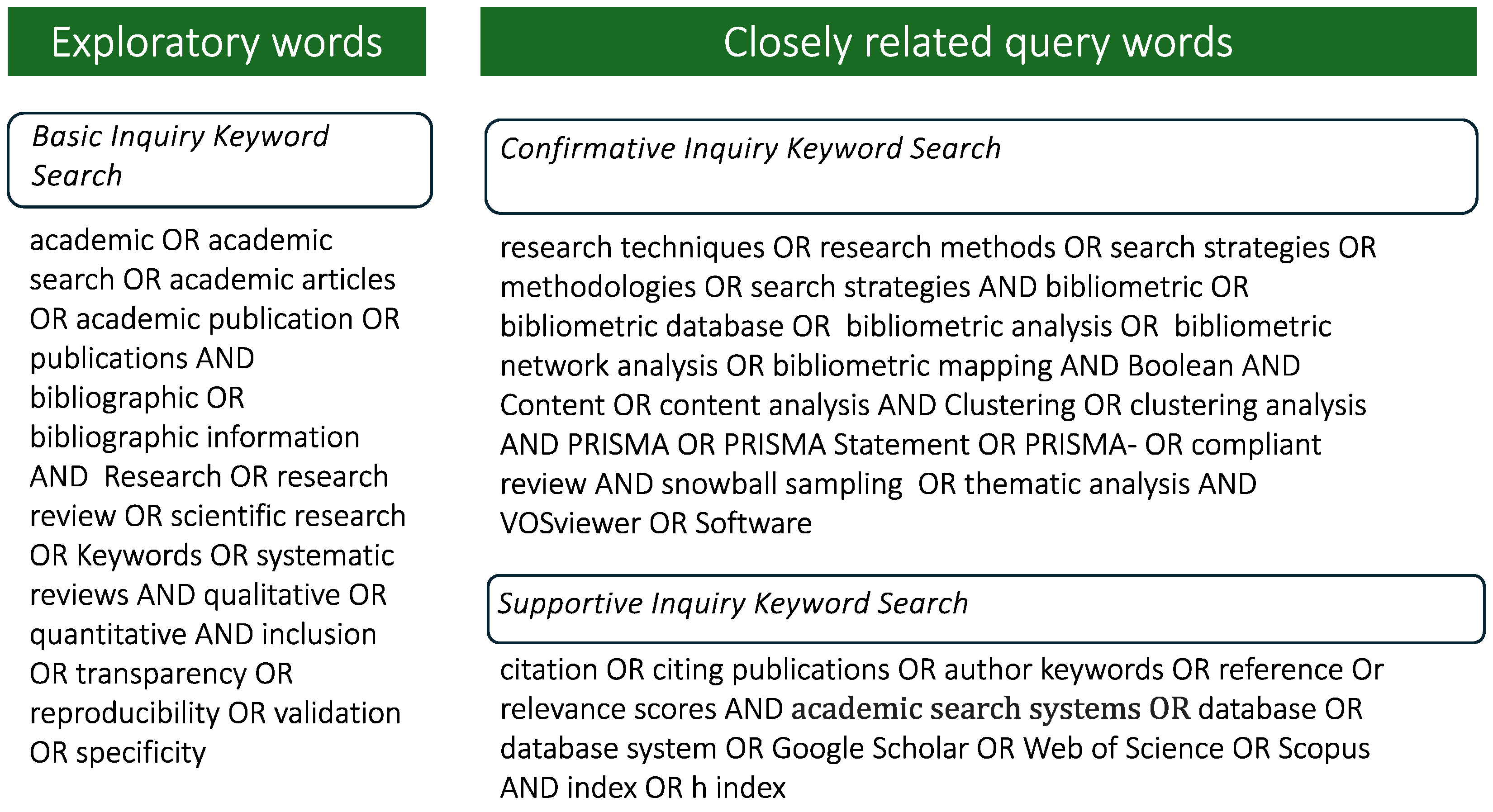

- Step 1: Following the initial search using inquiry keywords, also known as keywords, research terms, or coexistence words, it is essential to leverage these terms to pinpoint relevant sources [33,34]. This step involves searching for these words within the titles, abstracts, and keywords of literature [9,35]. Central to the research process is identifying the term or concept that forms the nucleus of the investigation. The choice of research terms or concepts is guided by the specific focus and objectives of the study, reflecting the researcher’s interests, expertise, and the prevailing discourse within scientific writing. By delineating the central theme of the research, researchers establish a solid foundation for subsequent literature searches and scholarly inquiry, ensuring coherence and relevance throughout the research process. Examples of such inquiry keywords include sustainable development, resilience, poverty or urban poverty, public health or healthy communities, livability, well-being, community well-being, walkability, urban streets, or pedestrianization. This step produces a refined list of keywords to guide the subsequent literature search. Initial searches may yield a broad range of results, including some that are potentially irrelevant, which will be filtered out in successive stages.

- Step 2: Once the research term or concept has been identified, the next step involves conducting targeted searches for references that include it in their titles. This step-focused approach ensures relevance and alignment with the research objectives. Respected databases such as Google Scholar, Web of Science, or Scopus are preferred for their comprehensive coverage and robust indexing systems [36,37,38,39]. The reasons for choosing these databases over others include the following:

- They cover diverse scholarly journals, conference proceedings, and scientific publications, ensuring comprehensive coverage across disciplines [36].

- Advanced search functionalities enable precise queries based on criteria like publication date, document type, and author affiliation, streamlining the literature review process [42].

- When a limited number of sources are retrieved from title searches, researchers may extend their search parameters to include the research term or concept in abstracts or keywords. This step produces a collection of papers directly relevant to the research term or concept, sourced from high-quality databases. Although initial results may include some irrelevant references due to ambiguous keywords, these will be filtered out in the next stage. Consider the following:

- Step 3: Determine the sources that can be obtained and classify them into independent groups, such as a body of literature in the form of a book or a chapter in a book, peer-reviewed scientific journals, or grey literature. Grey literature encompasses non-peer-reviewed sources such as reports, theses, working papers, and conference proceedings. While not subject to traditional peer review, grey literature often provides valuable insights and data not found in peer-reviewed publications [43]. Mention the justifications for focusing and not focusing on the style or styles you have chosen, as well as the pros, cons, or shortcomings. Justifications for concentrating on specific source types may vary based on research objectives, disciplinary norms, and the nature of the research question. For instance, a study aiming to establish theoretical foundations may prioritize books and peer-reviewed journals, while a research project focusing on emerging trends may prioritize grey literature and web-based sources. It is essential for researchers to carefully consider the strengths and limitations of each source type and select those most aligned with their research goals and methodology. This step produces classified groups of sources, allowing researchers to organize literature into categories such as books, peer-reviewed journals, and grey literature.

- Step 4: Specify the timeframe for source selection, elucidating reasons behind this choice and acknowledging associated opportunities and obstacles. The abundance of sources in the initial research stages often prompts narrowing the period to streamline the investigation. Additionally, the preference for relatively recent sources or the necessity to access historical works by pioneering theorists may drive this decision. This step produces a subset of papers grouped by timeframe, which helps focus on relevant and timely literature or include significant historical works as needed.

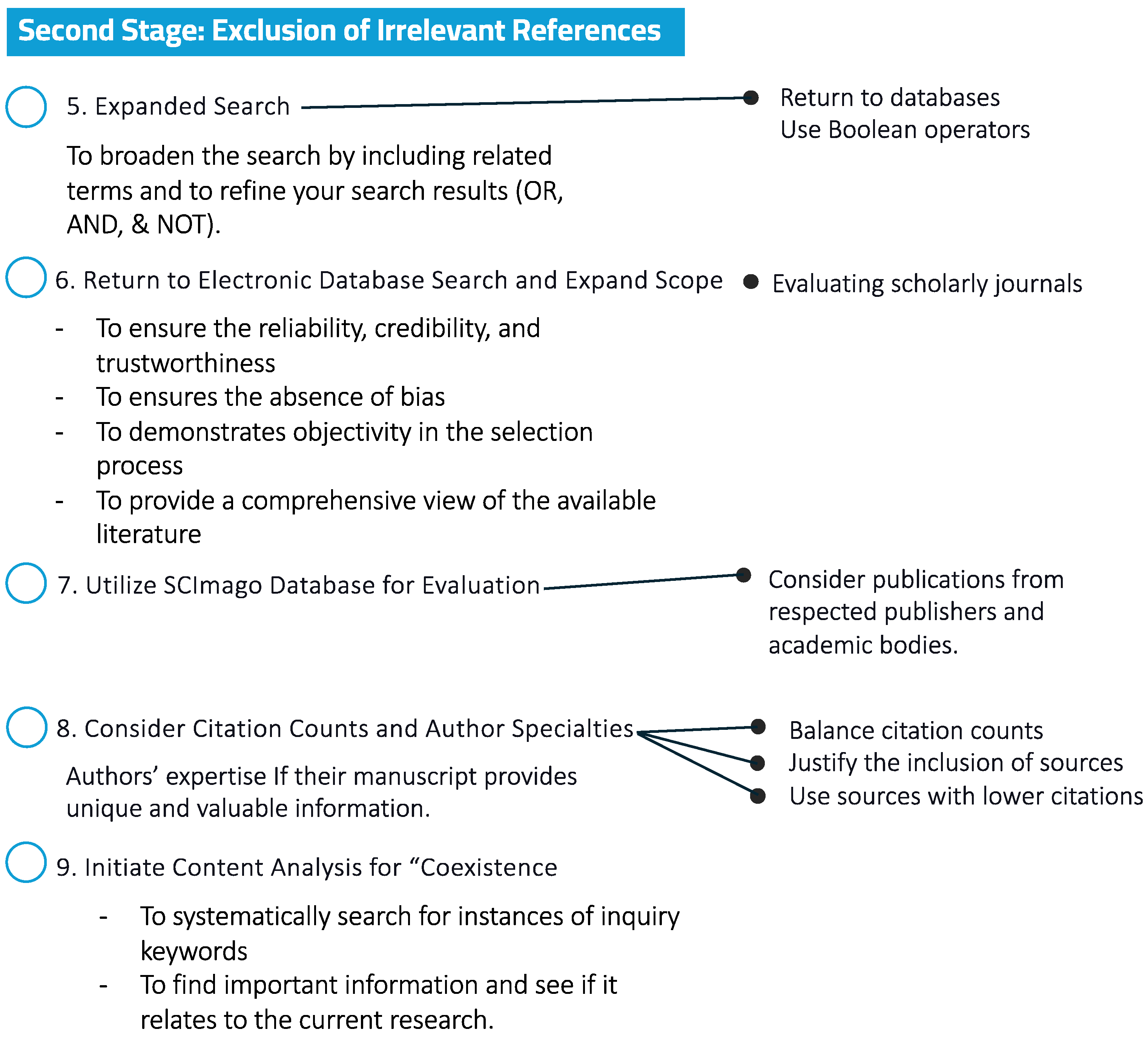

3.2. Second Stage: Exclusion of Irrelevant References

- Step 5: After initially searching for references containing the identified research words, keywords, or coexistence words in the literature titles, either term or concept, it is essential to return to electronic databases and expand the search scope by including relevant keywords or similar terms. This iterative process helps capture additional pertinent sources that may have not been retrieved in the initial search. Use Boolean operators such as “OR” and “AND” to combine different words or terms in the search query. “OR” expands the search to include any specified terms, while “AND” narrows the search to include only references containing all defined terms. Additionally, use “NOT” to exclude specific words or terms from search results, filtering out irrelevant sources [3,32,44].

- Step 6: Once detailed lists of publications have been compiled, it is essential to ensure the reliability, credibility, and trustworthiness of these references across multiple factors [45]. One effective method is to utilize databases such as SCImago, which provide comprehensive metrics and indicators for evaluating scholarly journals. Verify that the selected journals fall within the research subject area and are relevant to urban planning and design, for example. Recognize the multidisciplinary nature of city planning and design, encompassing fields such as humanities, environmental sciences, engineering, and social sciences. SCImago categorizes journals into different subject categories, including urban studies, geography, planning and development, education, behavioral studies, art, and humanities, facilitating targeted evaluation within relevant disciplines (Figure 6).

- Step 7: Prioritize journals with high rankings and quartiles within relevant subject categories, as they are more likely to publish high-quality [16], impactful research in scientific writing. On the other hand, identify the publishers of relevant literature, respected academic bodies, and websites of international and national institutions. Explain the rationale for including journals with high-impact and medium or low indices. This approach ensures the absence of bias and demonstrates objectivity in the selection process, providing a comprehensive view of the available literature.

- Step 8: By considering citation counts, author specialties, and rationales for including less reliable sources, researchers can ensure a rigorous and balanced approach to selecting references, thereby enhancing the credibility and integrity of the literature review process [46]. However, it is essential to exercise caution when interpreting citation numbers as a sole indicator of a study’s importance or reliability, as accidental factors may influence citation counts [47]. While publications with substantial citations are often considered authoritative and influential within the field [39], other factors should also be considered to assess a study’s overall impact and significance. Authors with expertise in relevant fields are more likely to produce credible and insightful research. Their knowledge and experience add credibility and enhance the reliability of the reference. In some instances, it may be necessary to resort to sources that do not have specific reliability or a limited number of citations. Justifications for including such sources are multifaceted:

- They may offer unique or valuable information not found elsewhere, enhancing the breadth and depth of the literature review.

- Credible sources may be scarce in emerging research areas, necessitating the inclusion of lesser-known materials to ensure a comprehensive overview.

- Despite fewer citations, incorporating sources from diverse perspectives enriches discussions and fosters a more balanced and inclusive literature review.

- Despite lower citation counts, sources may be deemed relevant and insightful based on rigorous evaluation of their content, methodology, and contribution to the research topic.

- Step 9: Employ qualitative content analysis techniques to systematically search for instances of inquiry keywords throughout the text [48,49,50]. It is essential to review each publication’s content to identify passages mentioning the terms, allowing for a qualitative examination of their contextualization in the literature. Complement this with numerical analysis to determine word frequencies, utilizing text analysis tools for quantitative insights [48]. By employing a summative approach to extract critical information from selected publications and assess their relevance to the ongoing research [51], researchers can ensure that the literature review incorporates high-quality evidence and supports the advancement of knowledge in the field.

3.3. Third Stage: Relevance Assessment of References

- Step 10: Qualitative coding provides a structured approach to content analysis, organizing, and interpreting qualitative data, such as text analysis [53]. Thematic analysis helps identify recurring words and patterns systematically [52,54]. Analyzing word frequency aids in understanding their significance. It enables researchers to derive meaningful insights, recognize patterns, and establish relationships within the data. To ensure relevance:

- Concisely extract critical information like research objectives, hypotheses, and results from selected publications.

- Assess how this information aligns with the ongoing study’s focus and objectives.

- Analyze the relevance and consistency of proposed hypotheses with the ongoing research’s theoretical framework.

- Evaluate the significance and implications of results from selected publications for the ongoing study.

- Avoid relying solely on support from previous research and prioritize publications with original findings.

- Emphasize selecting publications with rigorous study designs and methodologies to support ongoing research.

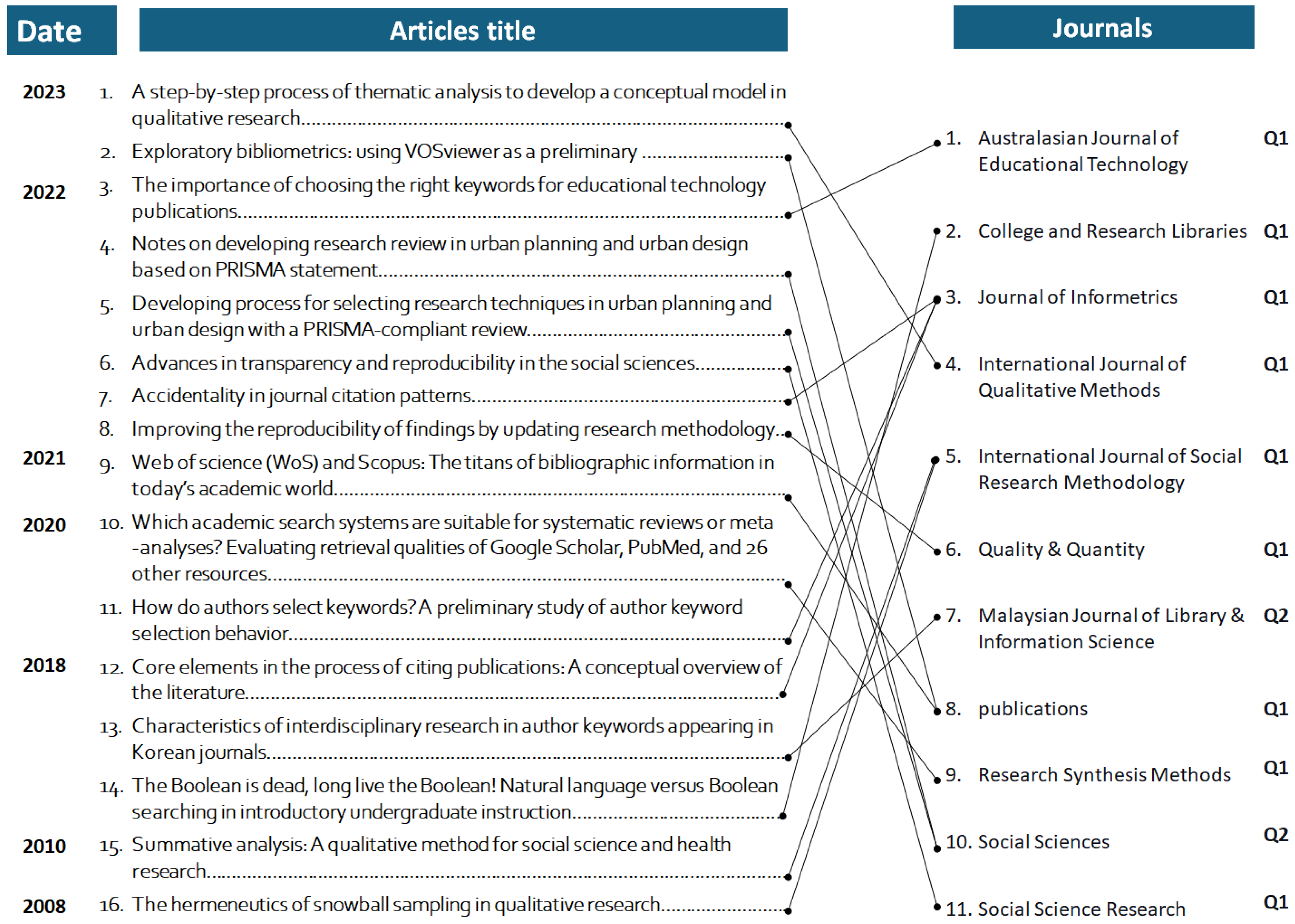

- There remains a meaningful idea for researchers to adopt when considering including and excluding references, which includes preparing a table that can be placed in the indexes. This table for journals consists of 12 pieces of information, as follows: numbers, date, journal title, subject area and category, the journal’s h index in the database, the best quartile in the database, cities (place of the case study), exploratory words (and their repetition in the text), closely related query words. It essential to concer the results relevant to the research that researchers in their scientific manuscripts can set up, and authors’ names, see Figure 7 as an example.

4. Discussion

- Utilizing inquiry keywords allows us to conduct a highly targeted search, effectively minimizing the inclusion of irrelevant materials. This focus is crucial for maximizing the sources’ relevance, ensuring that each retrieved reference significantly contributes to the research. For example, a prior study by Gusenbauer and Haddaway (2020) [56] demonstrated that keyword-based searches and scientific search systems significantly improve the specificity of retrieved scientific articles, thus enhancing the overall quality of literature reviews in social sciences.

- Moreover, this approach’s adaptability is notable. We can capture the full spectrum of relevant literature by incorporating synonyms, variations, and related terms into our search queries. This nuanced exploration uncovers hidden connections within the research landscape, enriching our understanding of the topic. For instance, the work of Corrin, Thompson, Hwang, and Lodge (2022) [57] highlighted how the inclusion of related terms in keyword searches revealed overlooked yet highly relevant studies, thereby broadening the scope of their literature review in scientific articles.

- Additionally, the transparency inherent in keyword-based searches is a significant advantage. This method provides a clear and understandable path for interpreting search results, fostering reproducibility and validation. The clarity of this approach ensures that other researchers can replicate and verify our findings, as Freese, Rauf, and Voelkel (2022) [55] emphasized in their methodological study on search strategies in scientific research.

- Combining the results produced by the inquiry keyword search method with additional filtering options, such as specific publication years or journal venues, enhances the accuracy of the search results. This filtering process increases the precision and relevance of the identified literature. Studies by Lowe et al. (2018) [32] and Liu et al. (2024) [44] have demonstrated the efficiency of these filters in improving the quality of systematic reviews in social sciences and computer science.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Paul, J.; Criado, A.R. The Art of Writing Literature Review: What Do We Know and What Do We Need to Know? Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 29, 101717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarafdar, M.; Davison, R.M. The Art of Referencing. Inf. Syst. J. 2020, 30, 787–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illinois Library. Tips for Searching Article Databases: Combining Terms (Boolean Searching). Available online: https://guides.library.illinois.edu/c.php?g=1191165&p=8712534 (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- Daldrup-Link, H.E. Writing a Review Article—Are You Making These Mistakes? Nanotheranostics 2018, 2, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abusaada, H.; Elshater, A. Decoding Near Synonyms in Pedestrianization Research: A Numerical Analysis and Summative Approach. Urban. Sci. 2024, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.R. Near Synonyms as Co-Extensive Categories: ‘High’ and ‘Tall’ Revisited. Lang. Sci. 2003, 25, 263–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lertcharoenwanich, P.; Phoocharoensil, S. A Corpus-Based Study of the Near-Synonyms: Purpose, Goal and Objective. Reflections 2022, 29, 148–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Molina, H.; Ullman, J.; Widom, J. Database Systems: The Complete Book; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2020; ISBN 0-13-606701-8. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Jian, K.; Simon, P. Data Mining: Concepts and Techniques, 3rd ed.; Morgan Kaufmann: Waltham, MA, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-12-381479-1. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, P.-N.; Steinbach, M.; Kumar, V. Introduction to Data Mining; Person: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 0321321367. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Grønmo, S. Social Research Methods: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches; University of Bergen: Bergen, Norway, 2024; ISBN 9781529616828. [Google Scholar]

- Walliman, N. Social Research Methods; SAGE Publications, Ltd.: London, UK, 2006; ISBN 9781412910620. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, R. An Introduction to Bibliometrics: New Development and Trends; Chandos Publishing: Kingston upon Hull, UK, 2017; ISBN 9780081021507. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, R. Handbook Bibliometrics; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2021; ISBN 9783110646610. [Google Scholar]

- Tahamtan, I.; Bornmann, L. Core Elements in the Process of Citing Publications: Conceptual Overview of the Literature. J. Inf. 2018, 12, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todeschini, R.; Baccini, A. Handbook of Bibliometric Indicators: Quantitative Tools for Studying and Evaluating Research; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co.: Weinheim, Germany, 2016; ISBN 9783527337040. [Google Scholar]

- Noy, C. Sampling Knowledge: The Hermeneutics of Snowball Sampling in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2008, 11, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, C.; Scott, S.; Geddes, A. Snowball Sampling. In SAGE Research Methods Foundations; Atkinson, P., Delamont, S., Cernat, A., Sakshaug, J.W., Williams, R.A., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Aghabozorgi, S.; Seyed Shirkhorshidi, A.; Ying Wah, T. Time-Series Clustering—A Decade Review. Inf. Syst. 2015, 53, 16–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iezzi, D.F. Cluster Analysis. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 966–969. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software Survey: VOSviewer, a Computer Program for Bibliometric Mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshater, A.; Abusaada, H.; Alfiky, A.; El-Bardisy, N.; Elmarakby, E.; Grant, S. Workers’ Satisfaction Vis-à-Vis Environmental and Socio-Morphological Aspects for Sustainability and Decent Work. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, A. Exploratory Bibliometrics: Using VOSviewer as a Preliminary Research Tool. Publications 2023, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusaada, H.; Elshater, A. Notes on Developing Research Review in Urban Planning and Urban Design Based on PRISMA Statement. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshater, A.; Abusaada, H. Developing Process for Selecting Research Techniques in Urban Planning and Urban Design with a PRISMA-Compliant Review. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megahed, G.; Elshater, A.; Afifi, S.; Elrefaie, M.A. Reconceptualizing Proximity Measurement Approaches through the Urban Discourse on the X-Minute City. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusaada, H.; Elshater, A. Knowledge-Based Urban Design in the Architectural Academic Field. In Knowledge-Based Urban Development in the Middle East; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 204–227. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Sierra, N.; Magro-Vela, S.; Vinader-Segura, R. Research on Disinformation in Academic Studies: Perspectives through a Bibliometric Analysis. Publications 2024, 12, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, M.S.; Stone, S.M.; Maxson, B.K.; Snajdr, E.; Miller, W. Boolean Redux: Performance of Advanced versus Simple Boolean Searches and Implications for Upper-Level Instruction. J. Acad. Librariansh. 2020, 46, 102234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochetkov, D.M. A Correlation Analysis of Normalized Indicators of Citation. Publications 2018, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, M.; Maxson, B.; Stone, S.; Miller, W.; Snajdr, E.; Hanna, K. The Boolean Is Dead, Long Live the Boolean! Natural Language versus Boolean Searching in Introductory Undergraduate Instruction. Coll. Res. Libr. 2018, 79, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S. Characteristics of Interdisciplinary Research in Author Keywords Appearing in Korean Journals. Malays. J. Libr. Inf. Sci. 2018, 23, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Liu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Bu, Y.; Li, X.; Cheng, Q. How Do Authors Select Keywords? A Preliminary Study of Author Keyword Selection Behavior. J. Inf. 2020, 14, 101066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Kang, H.-J.; Kim, M.; Kwon, G.H. Mapping the Intellectual Structure of Research on Surgery with Mixed Reality: Bibliometric Network Analysis (2000–2019). J. Biomed. Inf. 2020, 109, 103516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, J.E. An Index to Quantify an Individual’s Scientific Research Output That Takes into Account the Effect of Multiple Coauthorship. Scientometrics 2010, 85, 741–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranckutė, R. Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The Titans of Bibliographic Information in Today’s Academic World. Publications 2021, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Liu, W. A Tale of Two Databases: The Use of Web of Science and Scopus in Academic Papers. Scientometrics 2020, 123, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Baceta, M.-A.; Thelwall, M.; Kousha, K. Web of Science and Scopus Language Coverage. Scientometrics 2019, 121, 1803–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, C.; Hamidi, S.; Ewing, R. Validity and Reliability. In Basic Quantitative Research Methods for Urban Planners; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 88–106. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, J. Improving the Reproducibility of Findings by Updating Research Methodology. Qual. Quant. 2022, 56, 1597–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusaada, H.; Elshater, A. Revisiting Urban Street Planning and Design Factors to Promote Walking as a Physical Activity for Middle-Class Individuals with Metabolic Syndrome in Cairo, Egypt. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farace, D.; Schöpfel, J. Grey Literature in Library and Information Studies; De Gruyter Saur: Berlin, Germany, 2010; ISBN 9783598117930. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; An, S.; Wang, L.; He, Y.; Fan, Z. Parameter Identification Algorithm for Ship Manoeuvrability and Wave Peak Model Based Multi-Innovation Stochastic Gradient Algorithm Use Data Filtering Technique. Digit. Signal Process 2024, 148, 104445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Ali, T.; Gawai, R.; Elaksher, A. Fifteen-, Ten-, or Five-Minute City? Walkability to Services Assessment: Case of Dubai, UAE. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proske, A.; Wenzel, C.; Queitsch, M.B. Reference Management Systems. In Digital Writing Technologies in Higher Education; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 215–230. [Google Scholar]

- Mrowinski, M.J.; Gagolewski, M.; Siudem, G. Accidentality in Journal Citation Patterns. J. Inf. 2022, 16, 101341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis: A Step-by-Step Guide; SAGE Publications Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2022; ISBN 9781529701982. [Google Scholar]

- Neuendorf, K.A. The Content Analysis Guidebook; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zaidman-Zait, A. Content Analysis. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 1258–1261. [Google Scholar]

- Rapport, F. Summative Analysis: A Qualitative Method for Social Science and Health Research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2010, 9, 270–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; SAGE Publications Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 1473953243. [Google Scholar]

- Saldana, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; SAGE Publications Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 9781473902497. [Google Scholar]

- Naeem, M.; Ozuem, W.; Howell, K.; Ranfagni, S. A Step-by-Step Process of Thematic Analysis to Develop a Conceptual Model in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 16094069231205789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freese, J.; Rauf, T.; Voelkel, J.G. Advances in Transparency and Reproducibility in the Social Sciences. Soc. Sci. Res. 2022, 107, 102770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusenbauer, M.; Haddaway, N.R. Which Academic Search Systems Are Suitable for Systematic Reviews or Meta-analyses? Evaluating Retrieval Qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 Other Resources. Res. Synth. Methods 2020, 11, 181–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrin, L.; Thompson, K.; Hwang, G.-J.; Lodge, J.M. The Importance of Choosing the Right Keywords for Educational Technology Publications. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2022, 38, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, C.; Hadfield, M.; Hutchings, M.; de Eyto, A. Ensuring Rigor in Qualitative Data Analysis. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2018, 17, 160940691878636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlasti.com. Master Your Research Projects with the Power of AI. Available online: https://atlasti.com/ (accessed on 26 July 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abusaada, H.; Elshater, A. Beyond Keywords: Effective Strategies for Building Consistent Reference Lists in Scientific Research. Publications 2024, 12, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications12030025

Abusaada H, Elshater A. Beyond Keywords: Effective Strategies for Building Consistent Reference Lists in Scientific Research. Publications. 2024; 12(3):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications12030025

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbusaada, Hisham, and Abeer Elshater. 2024. "Beyond Keywords: Effective Strategies for Building Consistent Reference Lists in Scientific Research" Publications 12, no. 3: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications12030025

APA StyleAbusaada, H., & Elshater, A. (2024). Beyond Keywords: Effective Strategies for Building Consistent Reference Lists in Scientific Research. Publications, 12(3), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/publications12030025