The outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic (also known as the COVID-19 pandemic) early in 2020 created a huge global disruption in all aspects of social life. Acknowledged by the World Health Organization as a matter of public health emergency of global concern [

1], the pandemic caused worldwide restrictions to public gatherings, lockdowns, stay-at-home orders, etc. Educational institutions were temporarily closed to contain the pandemic, affecting millions of learners, as UNESCO showed in its report “Global monitoring of school closures caused by COVID-19” [

2]. Later these institutions were asked to rethink their operations in new formats, such as homeschooling or online schooling. According to UNESCO, approximately 72.9 percent of the world’s learner population, enrolled in schools, universities and colleges, was affected by the lockdown [

2] and had to adjust to the restrictions to physical spaces of educational purposes, such as classrooms, laboratories, libraries and/or bookstores. In this context, educational publishers from all continents recognized the right moment to step forward and support homeschooling, learning and research in a variety of ways. Some opened, at least temporarily, educational and research content to be consulted and/or downloaded free of charge, others developed special platforms to disseminate scholarly content or encouraged the acceleration of “open access” (OA) initiatives [

3]. Book sales dropped dramatically, exchanges of physical book formats were discouraged and difficult to manage, especially during lockdowns, but the need for quality content rose exponentially, as so adequately highlighted by the International Publishers Association [

3], educational media [

4,

5], thinktanks and research centers [

6], authoritative bloggers on the topic, independent or affiliated with presses or educational platforms [

7,

8], etc. Critical voices emphasized that many major publishers opened only selected educational resources, “engaging in last-minute, haphazard PR, hoping that the realization that publicly funded knowledge is inaccessible to most of us will not dawn too soon on the anxious tax payer” [

9]. The debate over free versus paid access to scholarly-led quality content intensified and the pandemic crisis made it obvious that decisions over open science cannot be postponed, especially in the case of university presses parented by public universities.

1.1. The Academic Open Books Debate as Part of Open Science Movement

Practically, the COVID-19 crisis accelerated the crisis in scholarly ecosystems, induced by the technological revolution and the digitization of the economy. While open access books in the pre-COVID-19 crisis were rather options embraced by small university presses or tackled in an experiential manner [

10], the lockdown created a huge demand for online quality material. According to the Federation of European Publishers (FEP), only in Italy, during the first one and a half months of school closure in 2020, 4.4 million digital materials were downloaded from the platforms of educational publishers. The FEP is cautious in drawing attention that “the provision of digital materials for free, which many publishers felt was the right thing to do given the situation, is nonetheless not sustainable as a strategy for the production and distribution of quality learning content” [

11]. The FEP also anticipates that “there is a risk that an attitude of expecting not to pay for digital content become even more entrenched—as exemplified also by increases in illegal copying of books in schools (as was the case in Malta, for instance). This is all the more of concern as public budgets may feel the effects of the crisis in the coming months, leading to a reduction in funds for educational institutions and libraries. It will be therefore essential that governments foresee suitable budget allocations to acquire educational resources in schools” [

11].

Researchers, publishers and/or activists who champion open science share the belief summed up by Hugh McGuire, Boris Anthony, Zoe Wake Hyde, Apurva Ashok, Baldur Bjarnason and Elizabeth Mays that “the history of human knowledge is written in, on, and with open, available, and accessible technologies: language, writing, paper, pens, typewriters, printing presses. No proprietary or closed technology has survived the tests of time to preserve and propagate the continuous progress of scholarly investigation. In the digital world, the movements of Open Web, Open Content Licenses, and Open Source Software tools continue with this imperative today” [

12] (p. 45). In her turn, Professor Christine Borgman analyzed the impact of digital technologies on academic life, pointing out that scholarship is at crossroads, with scholarly objects available online in multiple formats and places [

13] (p. 9). The technological availability posed serious questions concerning the quality of content, the prestige of publishing online, instead of resuming to the prestige of renowned publishers, copyright, production and circulation of knowledge. To sum up the features of open access research literature, it refers to free, online copies of peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers, technical reports, theses, working papers, scholarly monographs and book places [

13] (p. 100). Definitions carefully rule out of the open access research objectives vanity publishing and the by-passing of reviewing processes, underlining the fact that open access is a means to encourage the scientific dialogue and progress and not a target in itself [

14]. In most cases, there are no licensing restrictions on the use of open resources by readers, the developed copyright arrangement for such content allowing for free access for research, teaching and other purposes [

15].

International organizations such as UNESCO, OECD and the World Bank actively promote open access to scientific literature, in all its forms, insisting upon the fact that in such a way the engagement between research and society can be increased, leading to a higher social and economic impact of public research. So far, the efforts have led to the elaboration of the European Open Access Policy (EOAP). However, as OECD unfolds in its report on open science, the EOAP is not binding in the EU countries, “which are free to adopt the policy that best suits the needs of their own scientific community”, leading to a “mosaic of open access policies across Europe” [

14]. The practices range from the mandatory golden road for publications and data put in place by the Research Councils of the United Kingdom (RCUK) to the preference for gold open access in the Netherlands to the green road for publications in Germany. Recently, OECD identified as a landmark in the road toward enlarging the open science area the practice of the national research councils of the United Kingdom and the Netherlands that condition research grants to be awarded only to applicants who are committed to publishing their results, both publications and data, under open access conditions [

14].

The open science ecosystem consists of key actors and processes, such as researchers themselves, government ministries, research funding agencies, universities and public research institutes, libraries, repositories and data centers, private non-profit organizations and foundations, private scientific publishers, businesses, supra-national entities, scientific research production and dissemination, etc. [

14]. The literature on each of these actors is growing, especially with case studies and experiences shared by editors, librarians and professors, since many of the authors writing about open access research are also engaged in promoting open science [

10,

16,

17]. Those who are engaged in editing the open access scientific content and disseminating it to the public find themselves in the situation of “laying tracks while the train was already barreling toward” the editors [

10]. The implementation of open access strategies, especially for books, reveals that new procedures, conventions, workflows and business models need to be put in place, even if some of the most difficult barriers, those of identifying quality content and authors ready to share it, are overcome [

10].

1.2. Romanian Experience with University-Led Publishing and Open Access in Science

Academic books have a long tradition in Europe, with Cambridge University Press and Oxford University Press established in 1534 and 1586, respectively [

16]. Romania’s academic tradition is much younger. Romanian universities as entities emerged only in 1860, and academic book publishing did not fall in the responsibility of higher education institutions. To supply students with textbooks, monographs or other educational materials, alternative routes were found. For instance in Timisoara, when the Polytechnic school was founded (1920), a publishing house opened a section to edit the Mathematical Gazette for the use of professors and students, while professors hand-wrote their courses to provide educational support [

18]. Universities used reprographics to provide the educational resources, and the process went through strict editorial processes in terms of reviewing, accepting for multiplication and dissemination of the intellectual output, even if an ISBN was not provided for such books. For the academic career, such a multiplied manuscript counted as a book for tenure tracks and projected prestige to the author(s).

In 1990, the democratization of the Romanian society, the abolition of censorship for printed material and the necessity to rapidly supply new information to the diversified needs of the academic community (among other phenomena—with the proliferation of new academic degree programs and new higher education institutions) [

19], many universities decided to establish their own presses. The academic-led publishing was shared with many private, newly founded presses [

20] that supplied a large portion of the educational material, textbooks and monographs used in higher education. The scope of this research, though, was to focus only on university presses.

The emergence of e-books and e-commerce with books dramatically impacted the publishing houses, putting an end to the long-established economic models and supply chains. For secondary education, for instance, a large debate on the need for e-textbooks led to experimental projects for the production and dissemination of educational resources. In universities, however, practices are varied, with asymmetrical outcomes [

21].

Romania is engaged in promoting open science and open access to knowledge, both at the political-governmental level and through the initiative of dedicated organizations. The National Strategy for Research, Development and Innovation 2014–2020 [

22] includes as a priority, in the subchapter Access to Knowledge, the obligation to ensure and support open access by facilitating the access to information for the academic institutions and by stimulating Gold OA publishing for research financed through public funds. This adhesion to open access policies is reinforced in a subsequent document, Partnership for Open Government: The National Action Plan 2018–2020, which has a chapter dedicated to open data [

23]. In the tier of civil society, initiatives such as “Understanding Open Access” promoted by the Kosson foundation in 2012, created a breakthrough and mobilized the scientific community [

24]. In the same year, the Romanian Academy signed the document “Open Science for the 21st Century”, promoting the principles of open access and enhanced scientific dialogue [

25]. Yet, studies regarding Romanian open access scholarly writings are sparse and, to the best of our knowledge, there is no country-wide study that analyzes the policies of OA journals, although there are studies regarding OA policies. The various alternatives regarding open access are rarely present in the Romanian academic public debate and are missing from the domestic publishing practice. References to gold, green and/or hybrid access appear only in documents connected to research articles published in journals with a calculated impact factor, in evaluating the prestige of Romanian scholarship [

26], or during information seminars, guiding researchers. In the area of open book publishing, the focus of our study, the research is even less prominent, following a trend observed in other countries with much older publishing traditions [

16,

17]. As reports show, “unlike for journal articles, discussions around how to best achieve Open Access to books are still in a nascent stage, complicated by the large upfront costs associated with each published book” [

27]. Challenges for university presses are numerous, and accumulated experience is a valuable source of inspiration for the academic and publishing community [

28,

29].

We focused on university presses parented by public universities because they are the unequivocal signals that higher education institutions fulfill their research mission and are places of producing, transferring and disseminating (new) knowledge. In a World Declaration on Higher Education for the Twenty-first Century held at the UNESCO headquarters in Paris, signatory universities re-assessed that their core missions and values resided in contributing to “the sustainable development and improvement of society as a whole” through education, training, research and public service [

30]. Higher education institutions recognize their responsibility to “ensure that all members of the academic community engaged in research are provided with appropriate training, resources and support” (article 5.b) and to enhance their research capacities (article 5.c). University presses are not named as such, but they represent the element of infrastructure that underpins the research and education activities by providing the much-needed support to publish educational and research materials for the benefit of the academic community and for society as a whole. In the Romanian accreditation processes, higher education institutions must prove “that the discipline tenured university teachers have elaborated courses and other works necessary to the educational process, which completely cover the respective discipline issues, stipulated in the analytical syllabus” and that they “periodically organise with the teaching staff, researchers and graduates, scientific sessions, symposiums, conferences, round tables, and the reports are published in ISBN, ISSN scientific reports or in magazines dedicated to the organised activity” [

31]. Most publicly funded universities identified as part of the required support for producing and disseminating educational and research results the tier of a university press, connected to the interests and needs of the academic community, making available to their members the editorial services. Since they are part of a publicly-funded institution, Romanian university presses should respond to the same type of scrutiny regarding transparency, public service and availability as their parent institutions. The predominant model of operation concerning higher education institutions in Romania is that of public goods, present in the public, not-for-profit sector [

32] (p. 70).

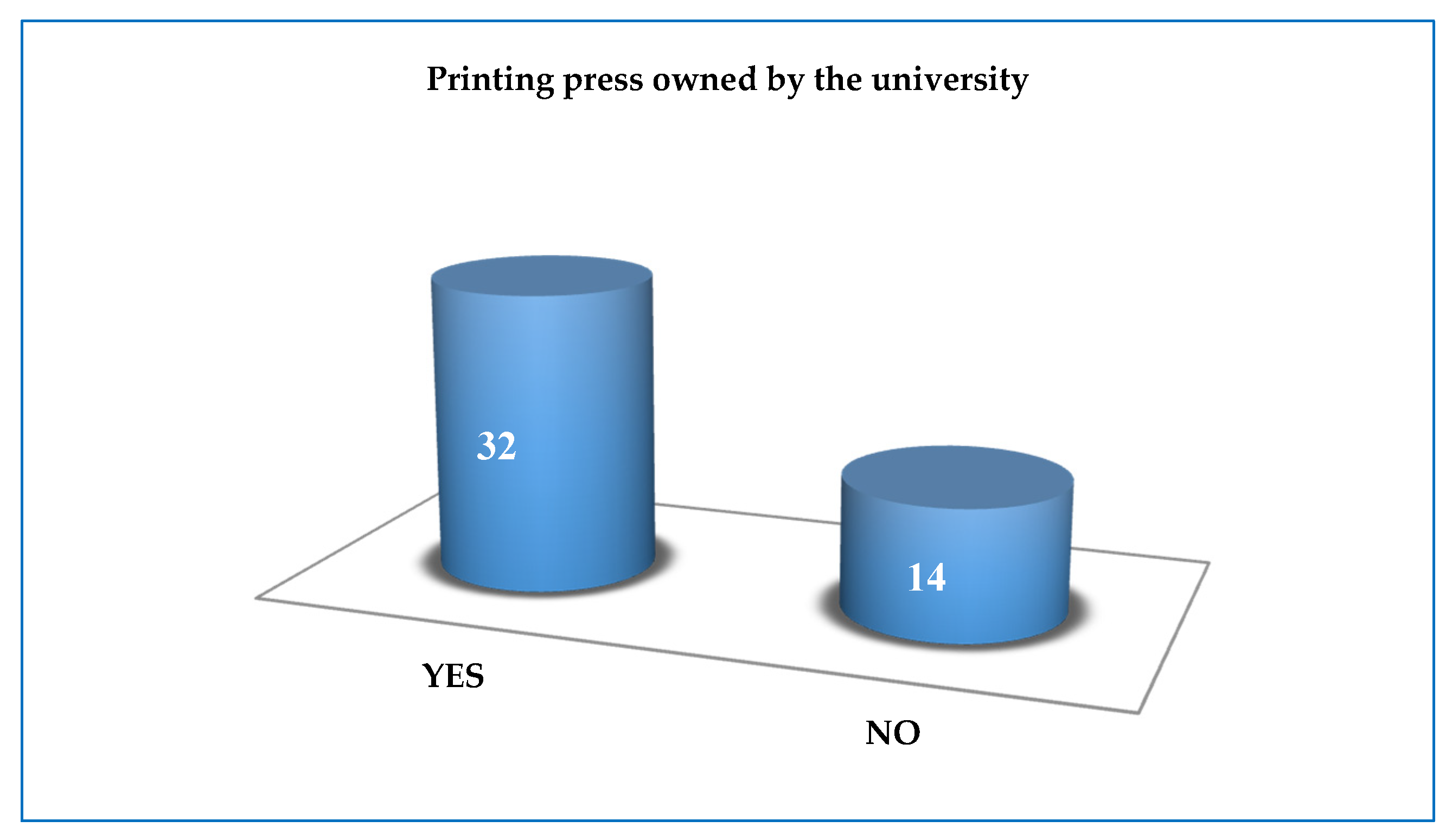

Drawing lessons from the scientific literature on scholarly open book publishing and from the Romanian realities, the present study aimed to fill in the missing piece on the existence and practices of university presses to meet the needs of the academic community, especially during the disruption produced by the COVID-19 lockdown, which collapsed access to physical books and resources for teaching, learning and carrying out new research. This study analyzed the response of the Romanian university presses to the COVID-19 crisis in terms of opening access to previously published books or by increasing the publishing of open access books in online formats. The objectives set forth by the research team were:

To map the world of Romanian university presses, parented by public universities;

To identify the interest toward open book publishing of these presses, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, as an instance of serving the academic community.