Towards a Business Model Framework to Increase Collaboration in the Freight Industry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Context

2.1. Collaboration and Collaborative Networks

2.1.1. Forms of Collaboration

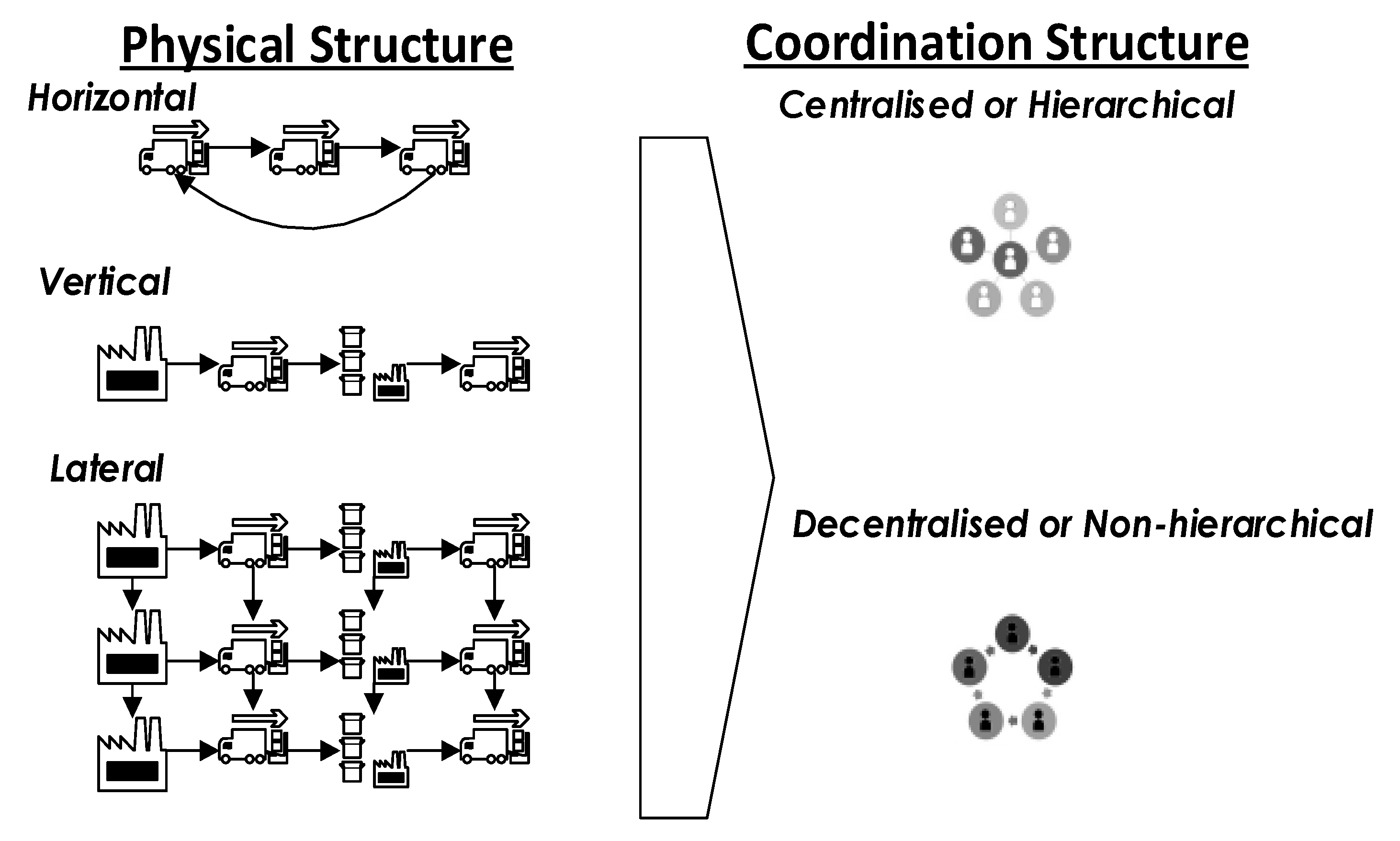

- Physical structure of collaborative networks: the physical structure of a collaborative network in transport is specific to the sector. Three categories for collaborative schemes in this industry have been proposed: vertical, horizontal and lateral [11,23]:

- Horizontal collaboration allows two or more unrelated or competing organisations at the same level of the logistics network that cooperate to share their private information or resources, such as transportation. According to [24], horizontal collaboration in transport can be categorized in two main streams: (a) Long-distance transportation considers lanes that use full truckloads to be carried from one origin to one destination. The key in this stream is to identify companies that use the same lane but in opposite directions for backhauling trips. This concept is extended in Section 2.2.2. (b) Urban transportation focuses on less-than-truckload requests and short distances. The aim of transport coalitions in this context is to synchronize operations in a way that minimizes the overall number of vehicles needed. Another approach proposed by [25] is the distinction made between two operational approaches: order sharing and capacity sharing.

- Vertical collaboration allows two or more organisations acting at different levels of the logistics chain, such as a receiver, a shipper, and a carrier, who share their responsibilities, resources and data information, to serve relatively similar end customers of a specific supply chain. Vertical collaboration in transportation predominantly relies on letting service logistics providers decompose transportation routes into multiple tiers. Then, each coalition partner serves one or more dedicated tier or level. This changes the interfaces between tiers, such as urban consolidation centres (UCCs) or satellites, into the main point of contact, where partners’ interactions and synchronizations determine the success of efficient deliveries [24].

- Lateral collaboration enables greater flexibility by combining and sharing capabilities, both vertically and horizontally.

- Coordination structure for collaborative networks: the form of collaboration depends on the type of coordination that is established among the members of the collaborative network. These types of coordination can be: hierarchical coordination, also known as centralised coordination; or non-hierarchical, also known as decentralised [21,22]. For the purposes of this study the terms centralised and decentralised collaboration are used:

- Centralised collaboration involves making decisions at a higher common level by generating synchronized instructions at lower levels, from a centralised perspective.

- Decentralised collaboration implies consensus, agreement of objectives, indicators and equality rules between partners. This collaboration is usually achieved through communication and negotiation processes between the partners. Thus, this kind of collaboration is performed from a distributed perspective.

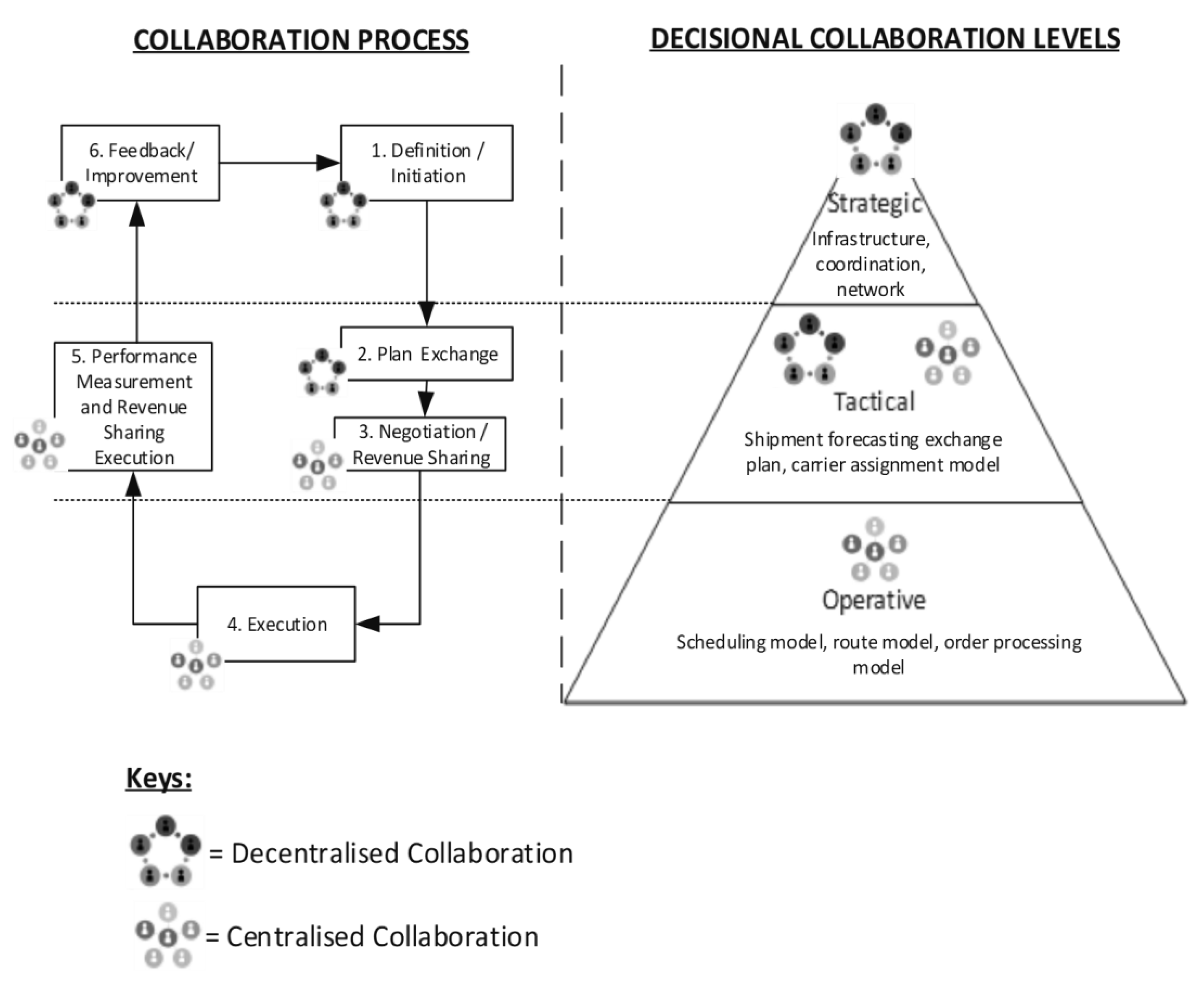

2.1.2. Collaboration Process

2.1.3. Technology Influencing Collaboration

2.2. Collaboration in the Freight Industry

2.2.1. Stages for Collaboration

- Transactional collaboration: logistics and transportation need consistent administrative practices and document exchanges. The first stage of collaboration consists of coordination and standardization of common administrative practices and exchange techniques, requiring information and communication systems.

- Informational collaboration: this level of collaboration relates to the mutual exchange of information such as shipping forecasts, volumes, locations and timing. At this level, it is noted that confidentiality and the process of competition can hinder collaboration. Information is the key to sharing. Without information sharing, the other levels of collaboration cannot take place [33].

- Decisional collaboration: this focuses on different collaboration opportunities to make planning and management decisions within logistics and transportation. These decisions can be made at different planning levels that are related to the time horizon and level of commitment in terms of the resources that are required. The three levels of planning are: Strategic, Tactical and Operational [11,24,34]:

- Strategic planning: this involves long term planning, often concerning timescales measured in years. It often results in committing large amounts of resources to service the strategy (including financial, human and capital resources). If an organisation is ready to collaborate, this level functions as the front-end agreement forming the foundation for the entire collaborative process. At this level, two main decisions are taken including the strategic partnership model and the network model. Also, the partners decide whether to enter into a coalition [8,35,36,37] depending on the perception the partners have about profit and potential partners’ characteristics [9,38,39]

- Tactical planning: this involves implementing the overall strategy and objectives of the organisation using tactics consistent with the strategy. It often involves shorter time horizons in terms of planning (medium term). It may involve planning horizons in terms of months instead of years. Generally, it will also involve lower levels of resource commitments. At this level, the following decision models are considered: Order Forecasting Model, Shipment Forecasting Model and Carrier Assignment Model. In addition to these and linked directly with the collaboration process, policies to distribute cost and benefits among coalition partners as part of tactical planning should be considered [24]. Therefore, there are two approaches to address the problem: (a) expected benefits are estimated before the partners decide to join the coalition and before deliveries start. In this approach, the information exchange is provided in full for the partners [9,40,41]; and (b) it compares the effects of different cost allocations or saving allocations schemes. In this approach the information exchange is limited to supply, demand and cost [38,42,43,44]

- Operational planning: this involves day-to-day operations at the ground level. The timescales involved will often be daily or weekly (short term). The resource commitments will be low. Operational plans should be consistent with tactical and strategic plans and should be about implementing the overall strategy. In the freight industry, operational decisions cover the process flow to fulfil the customers’ orders on a daily basis. At this level, three main decisions are taken: Scheduling Model, Route Model, and Order Processing Model. However, research in operational planning has focused mainly on solving three problems: (a) collaborative vehicle routing [10,45,46,47]; (b) crowd-sourced delivery routing [48,49,50,51]; and (c) ride sharing [52,53,54,55]

2.2.2. Strategies for Collaboration

- Route scheduling/planning: this strategy allows for more efficient supply chains and coordinated collaborative networks in a collaborative environment. Organisations involved in logistics need to implement some form of route scheduling and planning as part of their supply chain operations. However, the only way to achieve efficiencies in the supply chain is through collaboration between the different members of the supply chain. For example, vertical collaboration between suppliers and customers may help to optimise order cycles and delivery schedules. Horizontal collaboration for this strategy is also possible. For example, collaboration between carriers to consolidate deliveries for a specific route allows carriers better utilisation of capacity and reduces empty running. However, there is limited evidence of horizontal collaboration taking place, arguably because the business models do not support competition within the collaboration.

- Backhauling: this strategy of collaboration aims to reduce empty running by ensuring transport returns from a delivery trip with a load. An extension of this may be “forward hauling” where a vehicle is empty whilst ‘en route’ to pick up a load and therefore the objective of forward hauling is to reduce empty running for any legs of the journey. This can be considered as either a means to fill completely empty loads or to increase loads for vehicles running under capacity. This can be agreed between organisations on an ad-hoc basis or using freight exchange platforms. This kind of collaboration happens between members on the same level of the logistic network and normally implies collaboration between competitors i.e., companies moving goods on the same or very similar routes and/or feeding similar supply chain customers. Therefore, this strategy is related to horizontal collaboration.

- Freight exchanges: these are online service platforms for logistics providers and other transport companies. These platforms match freight demand and capacity, allowing users to search a database of available freight that needs to be delivered and advertise their available vehicle capacity, and post any transport requirements for tender. Online systems are normally subscription-based with a small charge for advertising and searching. This strategy of collaboration implies different logistics partners sharing information, and is related to lateral collaboration.

- Consolidation centres: these are logistics facilities situated in relative proximity to the area that they serve, from which consolidated deliveries are carried out. Goods destined for this area are dropped off, and are sorted and consolidated onto suitable goods vehicles for delivery to their final destinations using, in some cases, environmentally friendly cleaner vehicles. These facilities enable companies to group loads with one another and allow goods to be delivered on appropriate vehicles with a high level of load utilisation. This strategy is related to lateral collaboration.

- Delivery and servicing plans: these plans are designed to reduce the number of goods-vehicle trips generated by premises or wider areas with multiple premises. They are based on the principles of best practice in procurement, ensuring that goods are ordered within a single organisation, and potentially across multiple organisations in partnership, to reduce the total number of trips generated to serve those premises. In general, one organisation acts as the lead supplier—other suppliers channel their products through this lead to consolidate inbound deliveries. For example, this is particularly well suited for deliveries to retail outlets within centrally managed shopping centres, or central business districts with a concentration of offices and public buildings (e.g., local government or educational establishments). This strategy is related to vertical collaboration.

- Joint optimisation of vehicles and depots: essentially, this strategy involves two (or more) fleets working closely together, sharing a large portion of their joint resources to optimize the service of their current delivery tasks. This style of asset sharing is less evident in practice than backhauling and consolidation centres. However, the barriers to operation are primarily imagination, business models and appropriate technologies to make them work, rather than any capital expense, while the savings in cost and mileage can be quite significant. The idea behind this strategy is to treat the combined resources as if they were those of a single fleet operator, so that any vehicle in the combined fleet can serve any of the required deliveries. This strategy is related to horizontal collaboration.

2.2.3. Case Studies of Collaboration in the United Kingdom

- A total of 15 case studies relating to four industrial sectors have implemented different collaboration strategies: food (13%), transport (20%), public (33%) and retail (33%)

- Just five of the six strategies defined in Section 2.2.2 have been implemented within the 15 cases presented: Route scheduling/planning (7%), Freight exchange (7%), Consolidation centre (20%), Joint optimisation of vehicles and depots (27%) and Delivery and servicing plans (40%). However, this does not mean that Backhauling is a strategy that is not being used in the freight industry. This strategy is the easiest to implement operationally, needing a miniumum two organisations, while the other four strategies need the formation of a bigger network able to absorb the fixed costs and their operations require additional effort. Consequently, it seems reasonable to suggest that a Backhauling strategy is most likely deployed in the freight industry on an ad-hoc basis and therefore its real implementation by the sector has not been fully represented within the studies. In addition to this, Backhauling might be facilitated by other strategies like Freight exchanges and Joint optimization of vehicles and depots making the use of this strategy less visible, but extracting its benefits in wider strategies.

- The relationship between physical structure and coordination structure for the 15 case studies is presented in Table 2. In terms of coordination structure, centralised collaboration is predominant in 80% of the cases and decentralised collaboration represents just 20%. In terms of physical structure, vertical collaboration is predominant in 67% of the cases, followed by horizontal in 20% and lateral in 13%. Evaluation of the case studies show that horizontal collaboration always seems to be performed using a decentralized approach, while vertical and lateral collaboration adopt a centralized approach.

- All 15 case studies focus on collaboration at the operational level in the decisional collaboration stage. The strategic and tactical decisional collaboration stages are not detailed in the case studies analysed, nor are there details about the collaborative process itself. However, at first glance, it appears these cases follow a unique coordination structure for all the stages of the collaborative process. There seems to be a direct relationship between the different decisional collaboration stages and the collaborative process, which needs further analysis. In Section 2.1.2, it was highlighted that the centralised and decentralised forms of coordination structures should be used, depending on the stages of the collaborative process. It is necessary to emphasise again that the combination of both coordination structures may help to increase the degree of success in a collaborative environment. Section 3 addresses the findings and suggestions raised in this section.

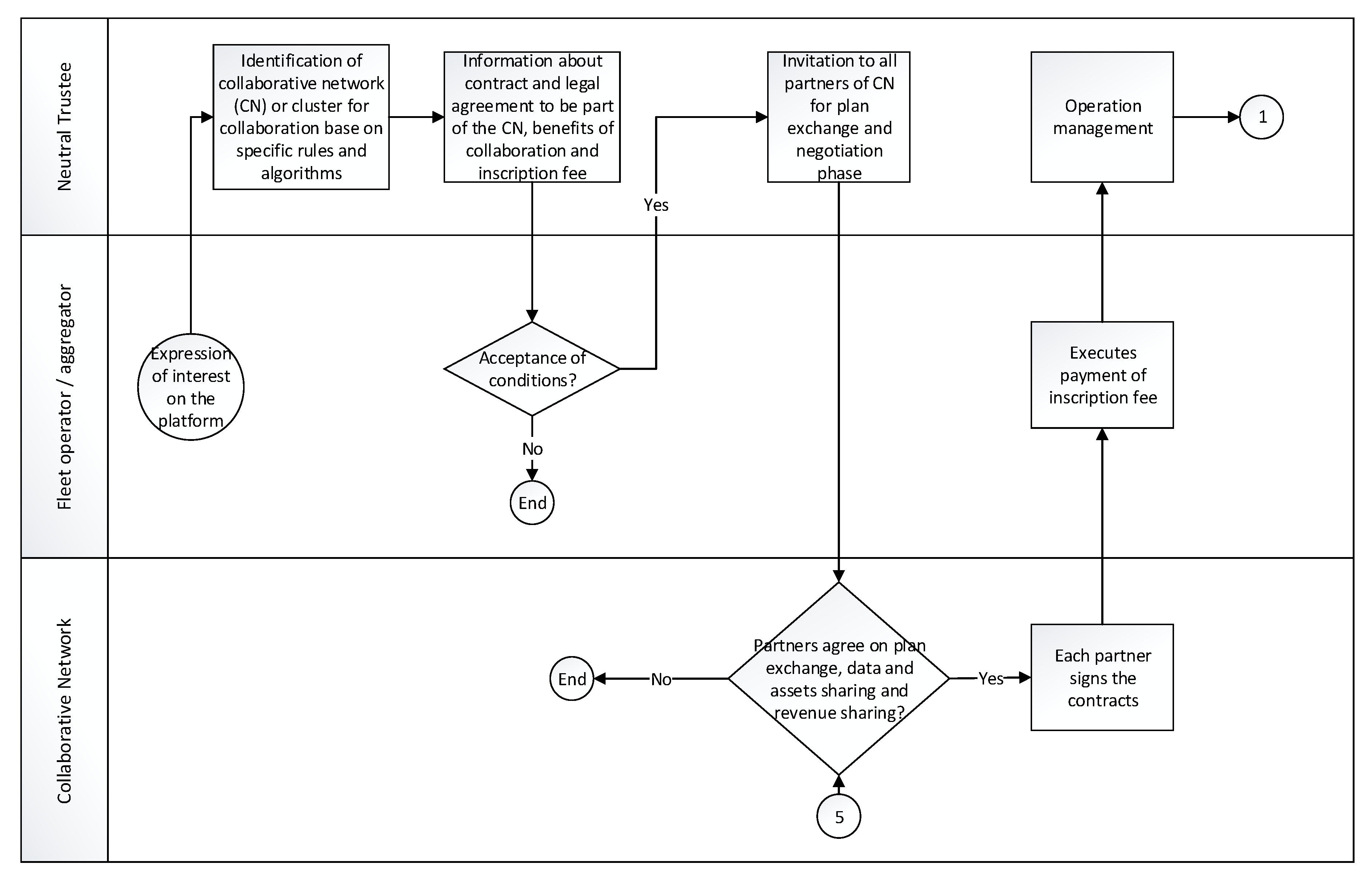

2.2.4. European Projects for Freight and Logistics Collaboration

- CO3—Collaboration Concepts for Co-modality [59]: the main contribution of the project is the definition of a straightforward methodology of three phases to boost horizontal collaboration between freight actors, using ICT as strategic support for the running of each phase. The phases of this methodology are: Identification, Preparation and Operation. The methodology suggests the existence of a “neutral trustee” facilitator of the collaboration between partners. The neutral trustee entity is an organisation that is responsible for ensuring that the collaborative network is constructed so that a fruitful long term, sustainable relationship between partners can be maintained on a flexible, community basis. The entity has also been referred as “freight traffic controller” (FTC) by [34]. However, the FTC is only in charge of the management of the freight operation among the network partners and the organizations do not intervene in the creation of the collaborative network.

- NexTrust [3,31,60,61]: the NexTrust project focuses on lateral collaboration, and extends the methodology proposed in CO3. Currently, there are more than 40 pilot schemes that are being implemented to prove the effectiveness of the methodology to accelerate collaboration. According to NexTrust the EU permits a neutral trustee to manage compliance within competition law. Partners in a collaboration agreement (possible competitors) could provide commercial data such as: volumes, delivery addresses and product characteristics, etc. to the trustee organisation. This trustee entity can hold and analyse the data given through contract terms. Therefore, compliance with EU competition law is guaranteed. In other words, a trustee organisation is necessary because, without it, it is not possible to transfer commercial data (even of competitors) while looking for efficiencies in the collaborative network. The trusted entity ensures that companies’ own legal compliance rules are respected and that confidentiality is in place, thus allowing the exchange of non-commercially sensitive information between the trusted collaborative partners.

- Clusters 2.0 [62]: CLUSTERS 2.0 extends the work undertaken in MODULUSHCA [63] and exploits the “low-hanging fruits” of the physical Internet. CLUSTERS 2.0 considers transport shipments to be open interconnected logistics networks using shared hubs, assets and loading units. The project has three core objectives: to advance the implementation of CargoStream, a shipper driven data collaboration platform; to implement a cluster community system comparable to a port community system among cooperating cluster partners; and to develop a new modular loading unit leading to the development of a standard.

2.2.5. Barriers for Collaboration and Ways to Overcome Them

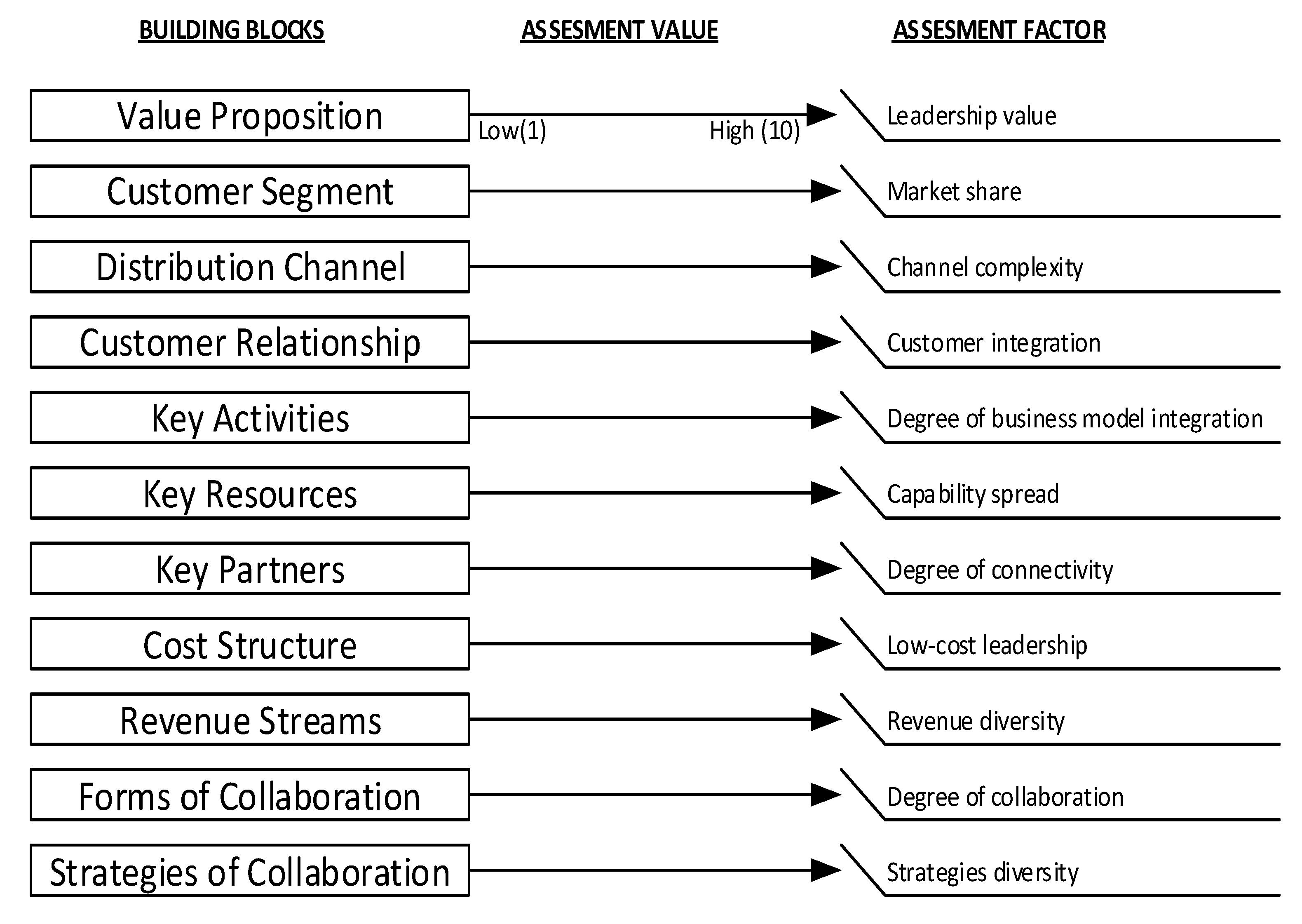

3. Proposed Freight Collaborative Business Model (FCBM)

- Value proposition: is an overall view of a company’s bundle of products and services that are of value to the customer.

- Customer segment: is a segment of customers a company wants to offer value to.

- Customer relationship: describes the link a company establishes between itself and the customer.

- Distribution channel: is a mechanism for getting in touch with the customer.

- Key activities: are the most important actions a company must take to operate successfully.

- Key resources: describe the most important assets (physical, financial, intellectual, or human) required to make a business model work.

- Key partnership: is a voluntarily initiated cooperative agreement between two or more companies in order to create value for the customer.

- Revenue model: describes the way a company increases income through a variety of revenue flows.

- Cost structure: is the representation of income of all the means employed in the business model.

- The Product Interface: is related to the core of the business and represents the value proposition building block. The other four interfaces (below) are directly interrelated with this building block.

- The Customer Interface: relates to the customer in terms of target customer to offer the value proposition, how it creates a strong relationship with them and the means to deliver the value proposition to them. This interface has three building blocks.

- The Infrastructure Management Interface: relates to how the company efficiently manages infrastructural or logistical tasks, to identify the resources and the type of network enterprise required to support the value proposition. This interface has three building blocks.

- The Financial Aspects Interface: relates to the revenue model and the cost structure that guarantee a business model’s sustainability. This interface has two building blocks.

- The Collaboration Interface: relates to the forms of collaboration used among business partners and the strategies implemented by the business that are related to the key activities. This interface has two building blocks.

4. Application of FCBM to Published Case Studies

- Nestlé and United Biscuits—identifying opportunities for reducing empty running through workshops run by Efficient Consumer Response (ECR) UK [73]. In October 2007, United Biscuits transported the first load of Nestlé products from Nestlé’s York factory to its own distribution centre in Bardon. This venture enabled United Biscuits to transport goods on Nestle’s behalf and has resulted in an annual saving of 280,000 km of road miles, approximately 95,000 litres of diesel and 250 tonnes of CO2, as well as generating a financial saving of £300,000 every year as a result of working together on back and forward hauling. These two competing organisations agreed at a senior management (strategic) level, that their products competed “on the shelf and not in the back of a lorry”, and as such worked through the cultural and service barriers that would have previously prevented this level of collaboration [1].

- Mars, United Biscuits, Saupiquet and Wrigley and a trustee logistics service provider (LSP)—logistics collaboration using CO3 methodology [74]. French retailers demand Full TruckLoad (FTL) deliveries from suppliers to their various warehouses throughout France. Vendor Managed Inventory (VMI) makes the suppliers responsible for the inventory replenishment at the warehouses. In 2010, a group of four suppliers, led by Mars, collaborated to fulfil the full truckload delivery requirement and to keep logistics costs under control. The collaboration involved Mars (Pet Foods: Whiskas, Pedigree, Sheba), United Biscuits (Biscuits: Delacre, BN), Saupiquet (Fish products) and Wrigley (candy and gum: Freedent, 5). All four producers have factories in France. From their factories, they transported their products to the shared warehouse in Orléans. The warehouse is operated by a LSP that acts as a neutral trustee and has the function of coordinating shipment, contacting transport companies, and sharing cost savings. From the joint warehouse, collaborative deliveries are made to the various retail warehouses in France. From there, the individual retailers supply their supermarkets. There is evidence of cost savings around 31% for each company collaborating.

- Returnloads.net—freight exchange platform [75,76]. Returnloads.net was founded in 2000. Initially the site was set up as a noticeboard to help haulage companies around the UK advertise their excess capacity and find return loads for their empty vehicles. In 2006, with the advent of new technologies, Returnloads.net became a fully functioning online freight exchange. This included developing an intelligent load and vehicle matching system, which automatically alerts members to available loads and vehicles that match their requirements. With ongoing development, Returnloads.net has continued to grow—with over 90,000 available haulage loads posted on the platform every month. It now has over 1500 users from across the UK including owner-drivers, freight forwarders and several of the country’s largest haulage firms. In 2016 loads totalling over 16.5 million miles were covered on the platform resulting in a potential saving of 25,514 tonnes of CO2.

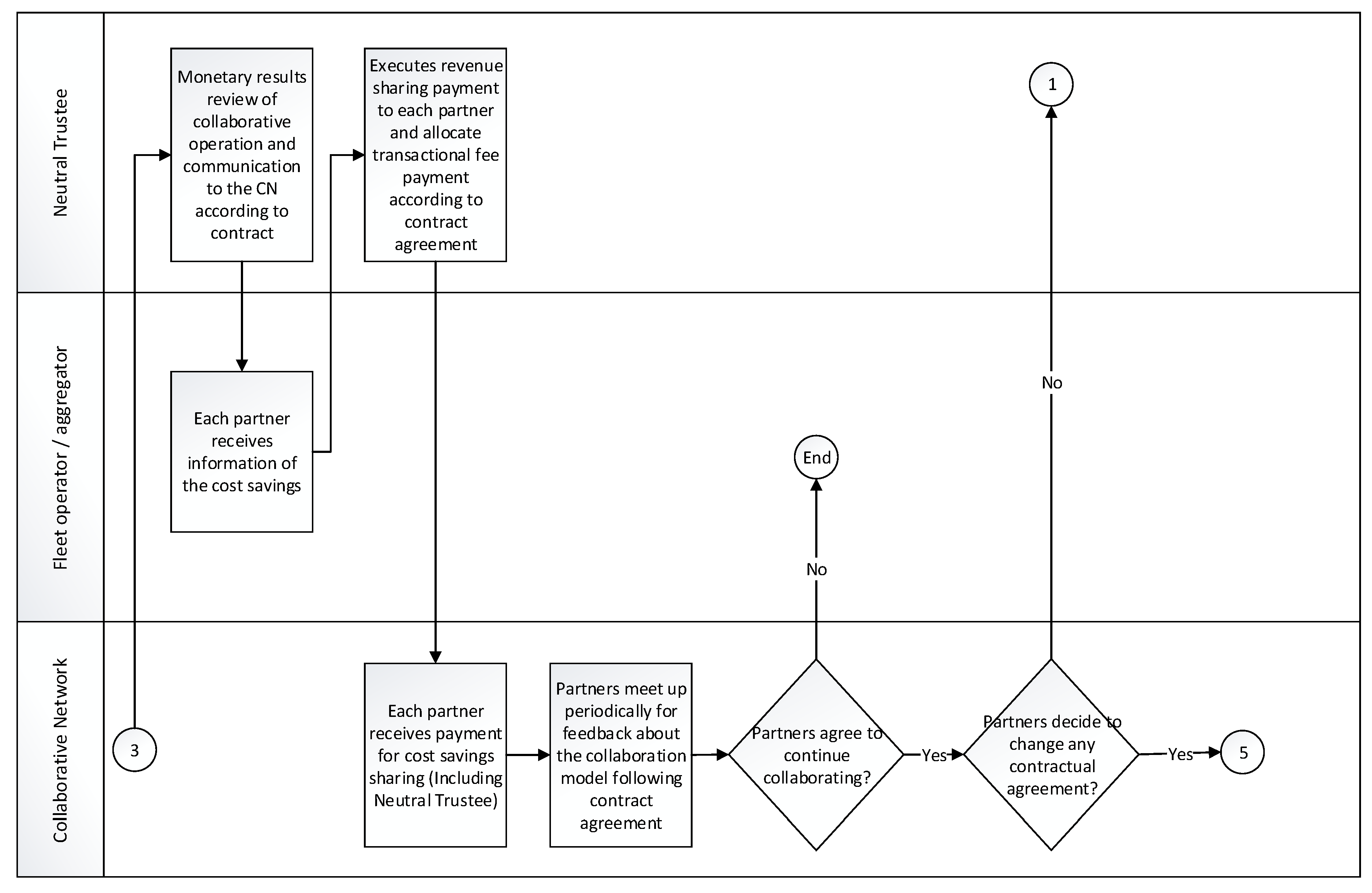

5. FCBM Instantiation

- The fleet provides data about a specific job and the agreed price to the platform. This data is stored into the FSL database and treated confidentially. Therefore, the different fleets do not have visibility of the data provided by other fleets.

- The FSL platform knows each fleets’ sharing rules and arrangements.

- The FSL platform jointly optimizes the fleets, optimizing routes and sharing opportunities by taking into account the various jobs entered by the fleets.

- The platform provides the results, including the cheapest option per job, a route for each fleet, and indicates any sharing opportunities.

- The Operational View shows the simplified process of choosing the cheapest option. The data in the database has been previously provided by the fleets in terms of total cost per kilometre or rate. The estimated gross cost is calculated by applying the agreed profit percentage to the net cost or rate. In this case, the cheapest option is selected for a different fleet than the originally contracted fleet.

- The Economic View shows the savings gained by each of the coalition partners using the FSL platform. Each of the coalition partners take their share of profit immediately after the customer fulfils payment. For this, it is proposed the savings are invested in a low-risk financial system that generates interest over a specific period. The financial system has been called FSL Bank for hypothetical purposes. The savings-sharing mechanism proposed is based on game theory and equally incentivizes two different behaviours, namely: (a) submitting contracts/jobs to the platform; and (b) performing the transport. The first behaviour incentivizes fleets to submit as many jobs as they have because they will still win their own profit if another fleet is chosen to perform the transport. The second behavior incentivizes fleets to keep costs low in order to be chosen by the platform. This approach builds competitiveness in the network between the fleets and offers economic benefits that will not be achievable by acting in isolation. Fleets that are part of the network, but do not actively participate, will not receive any benefits. The details of this saving–sharing mechanism are not discussed further in this publication. At the time of writing this mechanism was being evaluated by the stakeholders.

- The Benefits View summarizes the economic benefits for each of the fleets involved in the platform.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- TRL. Freight Industry Collaboration Study. London. 2017. Available online: https://trl.co.uk/sites/default/files/PPR%20812%20-%20Freight%20Collaboration%20Study.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2018).

- DfT. Domestic Road Freight Statistics United Kingdom 2016. 2017. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/627597/domestic-road-freight-statistics-2016.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2018).

- NexTrust. New Multi Supplier-Multi Retailer Platform: Biscuits Suppliers and Retailers are Setting Up a Collaboration for Sustainable Logistics. 2017. Available online: http://nextrust-project.eu/downloads/Press_Release_MRMS-Platform_EN_%281%29.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2018).

- Krajewska, M.A.; Kopfer, H. Collaborating freight forwarding enterprises Request allocation and profit sharing. In Container Terminals and Cargo Systems: Design, Operations Management, and Logistics Control Issues; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2007; pp. 365–381. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, M.; Zhang, Q. Supply chain collaboration: Impact on collaborative advantage and firm performance. J. Oper. Manag. 2011, 29, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.H.; Kuo, F.I. The study of relationships between the collaboration for supply chain, supply chain capabilities and firm performance: A case of the Taiwans TFT-LCD industry. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 156, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón, F. Desarrollo de una Arquitectura para la Definición del Proceso de Comprometer Pedidos en Contextos de Redes de Suministro Colaborativas. Aplicación a una Red Compuesta por Cadenas de Suministro en los Sectores Cerámico y del Mueble. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Politecnica de Valencia, Valencia, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schmoltzi, C.; Wallenburg, C.M. Operational Governance in Horizontal Cooperations of Logistics Service Providers: Performance Effects and the Moderating Role of Cooperation Complexity. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, S.; Moreno, P.; Adenso-Díaz, B.; Algaba, E. Cooperative game theory approach to allocating benefits of horizontal cooperation. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, S.; Derigs, U. Cooperative planning in express carrier networks—An empirical study on the effectiveness of a real-time Decision Support System. Decis. Support Syst. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okdinawati, L.; Simatupang, T.M.; Sunitiyoso, Y. Modelling Collaborative Transportation Management: Current State and Opportunities for Future Research. J. Oper. Supply Chain Manag. 2015, 8, 96–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Feliu, J.; Morana, J. Collaborative Transportation Sharing: From Theory to Practice via a Case Study from France. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjo25Oo6t_dAhWCE4gKHfiXAI0QFjAAegQICRAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fhalshs.archives-ouvertes.fr%2Fhalshs-00798319%2Fdocument&usg=AOvVaw3O7M4UX6eG67PvA1-TssIr (accessed on 29 September 2018).

- Audy, J.F.; Lehoux, N.; D’Amours, S.; Rönnqvist, M. A framework for an efficient implementation of logistics collaborations. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2012, 19, 633–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FSL. Truck Empty-Running the Target of New Collaborative Research Initiative. 2018. Available online: https://www.freightsharelab.com/freightsharelab2018/en/node/newsitem-truck-empty-running-the-target-of-new-collaborative-research-initiative (accessed on 25 September 2018).

- Sutherland, J. Collaborative Trasportation Management: A Solution to Current Transportation Crisis. Bethlehem. 2006. Available online: https://www.illinois-library.com/pdf/collaborative-transportation-management-a-2a0b7.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2018).

- Osório, A.L.; Camarinha-Matos, L.M.; Afsarmanesh, H. Enterprise collaboration network for transport and logistics services. IFIP Adv. Inf. Commun. Technol. 2013, 408, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Feliu, J.; Salanova, J.-M. Defining and Evaluating Collaborative Urban Freight Transportation Systems. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 39, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarinha-Matos, L.M.; Afsarmanesh, H.; Ollus, M. Ecolead and CNO base concepts. In Methods and Tools for Collaborative Networked Organizations; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Camarinha-Matos, L.M.; Afsarmanesh, H. Collaborative networks: A new scientific discipline. J. Intell. Manuf. 2005, 16, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeta, S.; Hernandez, S. Modeling of Collaborative Less-Than Truckload Carrier Freight Networks. 2011. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/2d69/8203895c57b575ce3a17db1d969d7ba4455f.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2018).

- Ribas Vila, I.; Companys Pascual, R. Estado del arte de la Planificación Colaborativa en la Cadena de Suministro: Contexto Determinista e Incierto. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjyzZ7I7N_dAhUbA4gKHfh9A4sQFjAAegQICRAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fupcommons.upc.edu%2Fbitstream%2Fhandle%2F2099%2F3911%2Fplanificacion_colaborativa.pdf&usg=AOvVaw0_fGbnocFNfzEdDJJOZPhN (accessed on 29 September 2018).

- Dudek, G. Supply Chain Management and Collaborative Planning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Caballini, C.; Sacone, S.; Saeednia, M. Planning truck carriers operations in a cooperative environment. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2014, 47, 5121–5126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleophas, C.; Cottrill, C.; Ehmke, J.F.; Tierney, K. Collaborative urban transportation: Recent advances in theory and practice. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdonck, L.; Caris, A.N.; Ramaekers, K.; Janssens, G.K. Collaborative Logistics from the Perspective of Road Transportation Companies. Transp. Rev. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadtler, H. A framework for collaborative planning and state-of-the-art. OR Spectr. 2009, 31, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilger, C.; Reuter, B.; Stadtler, H. Collaborative Planning. In Supply Chain Management and Advanced Planning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 263–284. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas, A.; Boza, A.; Cuenca, L.; Ortiz, A. Towards a framework for inter-enterprise architecture to boost collaborative networks. In On the Move to Meaningful Internet Systems: OTM 2013 Workshops; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 8186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, K.J.; Ragatz, G.L.; Monczka, R.M. An examination of collaborative planning effectiveness and supply chain performance. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2005, 41, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheij, H.; Augenbroe, G. Collaborative planning of AEC projects and partnerships. Autom. Constr. 2006, 15, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, K.; Bogens, M.; Stumm, P. NexTrust Deliverable 1.1 Report—Results of Identification Phase. 2017. Available online: http://nextrust-project.eu/downloads/D1.1_Identification_Phase.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2018).

- Vargas, A.; Boza, A.; Patel, S.; Patel, D.; Cuenca, L.; Ortiz, A. Inter-enterprise architecture as a tool to empower decision-making in hierarchical collaborative production planning. Data Knowl. Eng. 2016, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morana, J.; Gonzales-Feliu, J.; Semet, F. Urban consolidation and logistics pooling: Planning, management and scenario assessment issues. In Sustainable Urban Logistics: Concepts, Methods and Information Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.; Bektas, T.; Cherrett, T.; Friday, A.; Mcleod, F.; Piecyk, M.; Piotrowska, M.; Austwick, M.Z. Enabling the Freight Traffic Controller for Collaborative Multi-Drop Urban Logistics: Practical and Theoretical Challenges. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2017, 2609, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruijssen, F.; Cools, M.; Dullaert, W. Horizontal cooperation in logistics: Opportunities and impediments. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstrepen, S.; Cools, M.; Cruijssen, F.; Dullaert, W. A dynamic framework for managing horizontal cooperation in logistics. Int. J. Logist. Syst. Manag. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloos, M.; Kopfer, H. On the Formation of Operational Transport Collaboration Systems. Dyn. Logist. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guajardo, M.; Rönnqvist, M. A review on cost allocation methods in collaborative transportation. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palhazi Cuervo, D.; Vanovermeire, C.; Sörensen, K. Determining collaborative profits in coalitions formed by two partners with varying characteristics. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimms, A.; Kozeletskyi, I. Core-based cost allocation in the cooperative traveling salesman problem. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimms, A.; Kozeletskyi, I. Shapley value-based cost allocation in the cooperative traveling salesman problem under rolling horizon planning. EURO J. Transp. Logist. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisk, M.; Göthe-Lundgren, M.; Jörnsten, K.; Rönnqvist, M. Cost allocation in collaborative forest transportation. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hezarkhani, B.; Slikker, M.; Van Woensel, T. A competitive solution for cooperative truckload delivery. OR Spectr. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, B.; Chen, H. Profit allocation mechanisms for carrier collaboration in pickup and delivery service. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya-Torres, J.R.; Muñoz-Villamizar, A.; Vega-Mejía, C.A. On the impact of collaborative strategies for goods delivery in city logistics. Prod. Plan. Control 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouhader, H.; El kyal, M. Combining Facility Location and Routing Decisions in Sustainable Urban Freight Distribution under Horizontal Collaboration: How Can Shippers Be Benefited? Math. Probl. Eng. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gansterer, M.; Hartl, R.F. Collaborative vehicle routing: A survey. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanovermeire, C.; Sörensen, K.; Van Breedam, A.; Vannieuwenhuyse, B.; Verstrepen, S. Horizontal logistics collaboration: Decreasing costs through flexibility and an adequate cost allocation strategy. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gansterer, M.; Hartl, R.F. Request evaluation strategies for carriers in auction-based collaborations. OR Spectr. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, V.; Rouquet, A.; Roussat, C. The Rise of Crowd Logistics: A New Way to Co-Create Logistics Value. J. Bus. Logist. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buldeo Rai, H.; Verlinde, S.; Merckx, J.; Macharis, C. Crowd logistics: An opportunity for more sustainable urban freight transport? Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Nghiem, N.-V.-D.; Do, P.-T.; Le, K.-T.; Nguyen, M.-S.; Mukai, N. People and parcels sharing a taxi for Tokyo city. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Symposium on Information and Communication Technology, Hue City, Viet Nam, 3–4 December 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Krushinsky, D.; Van Woensel, T.; Reijers, H.A. The Share-a-Ride problem with stochastic travel times and stochastic delivery locations. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronald, N.; Yang, J.; Thompson, R.G. Exploring Co-Modality Using On-Demand Transport Systems. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linares, M.P.; Montero, L.; Barceló, J.; Carmona, C. A simulation framework for real-Time assessment of dynamic ride sharing demand responsive transportation models. In Proceedings of the 2016 Winter Simulation Conference (WSC), Washington, DC, USA, 11–14 December 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- wbcsd. Road Freight Lab: Demonstrating the GHG Reduction Potential of Asset Sharing, Asset Optimisation and Other Measures. 2016. Available online: https://www.wbcsd.org/Clusters/Climate-Energy/Resources/Demonstrating-GHG-reduction-potential-asset-sharing-asset-optimization-and-other-measures (accessed on 29 September 2018).

- wbscd. Road Freight Lab: A Low Carbon Freight Report under WBCSD’s Low Carbon Technology Partnerships Initiative (LCTPi). 2017. Available online: Https://www.wbcsd.org/Clusters/Climate-Energy/Road-Freight-Lab/Resources/A-Low-Carbon-Freight-report-under-WBCSDs-LCTPi (accessed on 29 September 2018).

- Todeva, E.; Knoke, D. Strategic alliances and models of collaboration. Manag. Decis. 2005, 43, 123–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogens, M.; Verstrepen, S. CO3 Position Paper: Added Value of ICT on Logistics Horizontal Collaboration: Identifying the Need for an Integrated Approach. 2013. Available online: http://www.co3-project.eu/wo3/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/CO3-D-4-4-Added-value-of-ICT-in-Logistics.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2018).

- Bogens, M.; Stumm, P. NexTrust Deliverable 2.1 Report—Network Identification. 2017. Available online: http://nextrust-project.eu/downloads/D2.1_Network_Identification_V7_%281%29.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2018).

- NexTrust. Collaboration in Logistics Is Achieving Breakthrough. 2017. Available online: http://nextrust-project.eu/downloads/Collaboration_in_logistics_is_achieving_breakthrough.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2018).

- ENIDE. Clusters 2.0. Open Netw Hyper Connect Logist Clust Dissem Mater. 2017. Available online: http://www.clusters20.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Clusters-2.0-Newsletter-1-v180109.01.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2018).

- PTV. Modular Logistics Units in Shared Co-modal Networks. 2016. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/docs/results/314/314468/final1-modulushca-finalreport-sectiona.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2018).

- Fabbe-Costes, N. Systèmes D’information Logistique et Transport. Available online: https://www.techniques-ingenieur.fr/base-documentaire/genie-industriel-th6/transport-et-logistique-42123210/systeme-d-information-logistique-et-transport-ag8030/ (accessed on 29 September 2018).

- Kale, R.; Evers, P.T.; Dresner, M.E. Analyzing private communities on Internet-based collaborative transportation networks. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2007, 43, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenks, C.; Jencks, C.; Navarrete, J.; Baker, T.; Delaney, E.; Hagood, M. Freight Data Sharing Guidebook. Washington. 2013. Available online: https://www.nap.edu/read/22569/chapter/1 (accessed on 29 September 2018).

- Eckartz, S.M.; Hofman, W.J.; Van Veenstra, A.F. A Decision Model for Data Sharing. In Electronic Government, Proceedings of the International Conference on Electronic Government, Dublin, Ireland, 1–3 September 2014; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; Volume 8653, pp. 253–264. [Google Scholar]

- Greening, P.; Piecyk, M.; Palmer, A.; McKinnon, A. An Assessment of the Potential for Demand-Side Fuel Savings in the Heavy Goods Vehicle (HGV) Sector. 2015. Available online: https://www.theccc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/CfSRF-An-assessment-of-the-potential-for-demand-side-fuel-savings-in-the-HGV-sector.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2018).

- Nadarajah, S.; Bookbinder, J.H. Less-Than-Truckload carrier collaboration problem: Modeling framework and solution approach. J. Heuristics 2013, 19, 917–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A. The Business Model Ontology—A Proposition in a Design Science Approach. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Norton, D. The Balanced Scorecard—Measures That Drive Performance. Harvard Bus. Rev. 1992, 70, 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- ECR. 2degrees. Transp Collab Guid. 2015. Available online: https://www.2degreesnetwork.com/groups/2degrees-community/resources/igd-guide-transport-collaboration/ (accessed on 4 April 2018).

- Guinouet, A.; Jordans, M.; Cruijssen, F. CO3-Project. CO3 Case Study Retail Collab Fr. 2012. Available online: http://www.co3-project.eu/wo3/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/20121128-Mars-CO3-Case-Study.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2018).

- Returnloads.net. 2018. Available online: https://www.returnloads.net/ (accessed on 4 April 2018).

- DfT. Freight Carbon Review. Moving Britain Ahead. 2017. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/590922/freight-carbon-review-2017.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2018).

- Vargas, A.; Boza, A.; Patel, S.; Patel, D.; Cuenca, L.; Ortiz, A. Risk management in hierarchical production planning using inter-enterprise architecture. In Risks and Resilience of Collaborative Networks, Proceedings of the Working Conference on Virtual Enterprises, Albi, France, 5–7 October 2015; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case Study—Company Name | Partner | Sector | Decisional Collaboration | Physical Form of Collaboration | Coordination Form of Collaboration | Strategy of Collaboration | Results in the Collaboration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pall-Ex | Unidentified retailer | Retail | Operational | Vertical | Centralised | Freight Exchange | Retailer reported annual savings of 890 tonnes of CO2. |

| Nestle | United Biscuits | Food | Operational | Horizontal | Decentralised | Joint Optimisation of Vehicles and Depots | Annual saving of 280,000 km of road miles, approximately 95,000 L of diesel and 250 tonnes of CO2, as well as generating a financial saving of £300,000 every year through working together on back and forward hauling. |

| Kimberley Clark | Manufacturers | Food | Operational | Vertical | Centralised | Joint Optimisation of Vehicles and Depots | Whilst not quantified, the operators reported savings on km and reduced transport costs. |

| Sainsbury’s | NFT and 240 manufacturers | Retail | Operational | Vertical | Centralised | Consolidation Centre | Reduction of Sainsbury’s carbon footprint: 4.6 million kg CO2. NFT fleet emissions reduction: 1.9 million kg of CO2. |

| Almo | Supplier | Public | Operational | Vertical | Centralised | Delivery and Servicing Plans | Deliveries being reduced from the main supplier by two-thirds. |

| Emirates Stadium | Supplier | Public | Operational | Vertical | Centralised | Delivery and Servicing Plans | Reduction in staff’s time dealing with deliveries and also saves the company money by having fewer invoices to process as well as reducing vehicle movements. |

| DHL | Retailers in Bath and Bristol | Retail | Operational | Vertical | Centralised | Consolidation Centre | Reduction of 78% in vehicle movements, savings of 154 tonnes of CO2 and 5 tonnes of NOx and over 17,900 vehicle trips. |

| Southwark office DfT | Suppliers | Public | Operational | Vertical | Centralised | Delivery and Servicing Plans | Not available. |

| Wisbech Roadways | 3 hauliers | Transport | Operational | Horizontal | Decentralised | Joint Optimisation of Vehicles and Depots | Empty running was lower (19%) and vehicle fill (85%) was higher than the industry average and resulted in taking vehicles off the roads. |

| National confectioner | Customer and competitor | Transport | Operational | Lateral | Centralised | Route Scheduling/Planning | Help to utilise the company’s assets, and reduce overall supply chain mileage. |

| TNT Olympic studies | Customers | Transport | Operational | Vertical | Centralised | Delivery and Servicing Plans | Not available. |

| Superdrug | Next | Retail | Operational | Horizontal | Decentralised | Joint Optimisation of Vehicles and Depots | Companies decided to share a vehicle and loads were consolidated and a vehicle was taken off the road to the benefit of both organisations. |

| London Boroughs Consolidation Centre | Camden, Waltham Forest and Enfield Councils | Public | Operational | Lateral | Centralised | Consolidation Centre | 41% reduction in CO2 emissions 51% reduction in NOx emissions, 61% reduction in PM) and over 70% vehicle capacity utilisation has been achieved. |

| Sainsbury’s | Department for Transport (DfT), Freight Transport Association (FTA) and Noise Abatement Society (NAS) | Retail | Operational | Vertical | Centralised | Delivery and Servicing Plans | Sainsbury’s reported improvements in fuel consumption of 5.7% for night-time operations compared to daytime equivalents. |

| Sutton Council | Suppliers | Public | Operational | Vertical | Centralised | Delivery and Servicing Plans | It was expected that it would achieve a carbon saving of at least 37,700 kg CO2. |

| Physical Structure | Coordination Structure | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Centralized | Decentralized | Total | |

| Horizontal | 3 | 3 | |

| Vertical | 10 | 10 | |

| Lateral | 2 | 2 | |

| Total | 12 | 3 | 15 |

| Barriers/Limitations for Collaboration | Author | Strategies to Overcome Them | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shipper concerns of having a different carrier from its usual contracted carrier to ship its goods. | [20] | Concerns over branding could be resolved through use of independent third parties and non-liveried vehicles. Involving the shipper into the alliance, through agreements and incentives for the shippers to accept transporting their goods by different carriers than the usual, showing them the advantages of collaboration. |

| 2 | Purchasing power for small operators to access information and communication technologies (ICT) is limited. | [20] | Create alliances between small operators that allow them to share the cost of ICT tools and take advantage of scale economies. |

| 3 | Private firms are concerned that data about their operations might be used by competitors to gain business advantage. | [64,65,66,67] | Possible interventions to overcome privacy constraints are anonymisation by filtering of sensitive information and aggregation of data, thus, only publishing a selection of data properties and values. Using a trustee figure that is neutral and impartial where the data is stored and shared in a confidential environment to optimise routes and schedules and where each partner just has access to their own data and the centralised and optimised schedule for day-to-day operations. |

| 4 | Legal barriers, there are laws that interfere with the ability to share data: competition law. | [1,13,64,66,68] | The European Union (EU) recommends the use of a neutral trustee, to whom different stakeholders give data to be held and analysed preventing the transfer of commercial date such as, volumes, delivery addresses, costs, product characteristics, etc. |

| 5 | Lack of human resources, especially for small operators. | [66] | By giving to a central entity the authority of decision making in terms of optimisation and route scheduling for a group of partners that are collaborating looking for efficiencies in capacity, cost and societal and environmental benefits and which have agreed through specific contracts to follow the central decisions. In this way, there is no need to increase utilisation of human resources for fleet operators. |

| 6 | Significant coordination is needed to achieve data and asset sharing and to accomplish work. | [66] | In a centralised structure collaboration scheme, the central coordinator is responsible for coordination of the partners in the collaboration and the partners are committed to follow central instructions to allow the collaboration scheme to work. |

| 7 | Lack of available accurate data. | [1,67,68] | Definition of data structure requirements for collection of unified and accurate data for collaboration. The confidentiality of data collection will be defined through contracts between the partners in the collaboration and the central trustee authority. |

| 8 | Lack of trust and common goals. | [1,20] | Use of clear contract agreements, where partners define confidentiality policies, service levels agreements, penalties in case of failing, payment conditions, coordination structure, management of unexpected events and contract duration. |

| 9 | Lack of a fair allocation mechanism for collaboration revenues. | [1,13,20,69] | Giving different options for revenue sharing to the partners and showing them the cost benefits of each option will allow them to choose, during the negotiation phase, which mechanism will be used for revenue sharing. |

| 10 | A neutral third party is required to facilitate collaboration. | [69] | A trustee figure is necessary to implement collaboration. The trustee needs to be a connector between the collaboration partners. Partners might be reluctant to accept a third party. But, through contracts between each partner and the trustee party, it is possible to overcome this. |

| 11 | There are clear regional imbalances in freight movement, with high volumes of loads from one side going to another and less in reverse. | [1] | Use the practice of triangulation, where a truck is diverted from its main back route to a third point in order to pick up a return load, potentially increasing the mileage but reducing the amount of empty running. |

| 12 | Load compatibility can restrict the ability for loads to be shared. | [1] | Matching companies moving similar products with similar handling equipment on similar types of vehicles. |

| 13 | Responsibility for transportation operations. | [64] | If the collaborations for logistics sharing follow a contract or a chart where the responsibilities are well defined, these questions will not constitute an obstacle to sharing. |

| 14 | Unawareness of the benefits of participating in collaborative projects. | [65] | Engagement of stakeholders to participate in collaborative networks is crucial. During the initial engagement, it is necessary to show to the possible partners the real benefits of similar collaborative projects and if possible estimated benefits of the project that they are being asked to participate in. |

| 15 | High risk of strategic behaviour in auction collaborative process. | [47] | Effective profit-sharing mechanisms are needed, since these have the potential to impede strategic behaviour. |

| Business Model Component | Business Cases | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nestle and United Biscuits | Mars, United Biscuits, Saupiquet and Wrigley | Returnloads | |

| Value Proposition | Collaboration between competitors to reduce empty running | Collaboration using a neutral trustee (LSP) to comply with customer requirements | Freight Exchange service |

| Customer segment | Retailers and their distribution centres in Midlands | Distribution centres in France | Fleets and shippers in UK |

| Customer relationship | _Customers were consulted to agree in the brand identity in case products of different brands need to be transported in the competitors trucks. | _Close relationship to be able to comply with the mandatory customer request of full truckload deliveries to their distribution centres | _Close relationship to inform the functionality of the platform, including freight alerts to suitable members aiming personalization |

| Channels | Retail | Retai CO3 Network | Digital platform that connects offer and demand |

| Key activities | _Produce summary of lanes and volumes _Identify potential collaborative lanes _Agree rates on lane by lane basis _Agree KPI’s and review mechanism _Run Pilot _Review Pilot _Roll Out | _Legal and formal contract between partners _Trustee figure responsible for coordination of shipments and gain sharing allocation _Negotiation and selection between partners of mechanism of saving cost sharing (cost per shipment, Shapley value and equal profit margins) | _A carrier places a load to be subcontracted out or a shipper posts a load that needs delivering _Each load will be matched to suitable members and freight alerts will be sent out to them via emai _Fleets and shippers negotiate rates and payment conditions |

| Key resources | Shared fleet assets and human assets | Shared shippers assets, human assets and processes definition | Digital platform, human assets and processes definition |

| Key partners | Competitors | Complementary products partners and trustee | No partners involved for collaboration |

| Revenue Streams | _Non saving cost sharing nor subscription fee. _There is evidence of cost savings for both partners and reduction of emissions | _For trustee: Partners pay to the trustee/LPS per: (1) The coordination of the shipments and the communication with transport companies. (2) The gain sharing and fair cost allocation _For shippers: cost savings | Annual fee subscription plan |

| Cost structure | _Time cost for attending to workshops _Operational cost | _Time cost for attending to meetings _Operational cost | _Operational cost _Digital platform maintenance _Advertising |

| Forms of collaboration | _Horizonta _Decentralised | _Horizonta _Centralised/Decentralised | _Latera _Centralised |

| Strategies | _Joint optimization of assets | _Route scheduling/planning _Joint optimization of assets | _Freight Exchange |

| Assessment Value Keys | |||

| Highest = 10 | |||

| Medium = 5 | |||

| Lowest = 0 | |||

| Business Model Building Blocks | Description |

|---|---|

| Value Proposition | The collaboration between competitors and non-competitors to reduce empty running by using a neutral trustee based on an online platform to initiate the collaboration process and, to arrange scheduling and routing among partners and cost sharing. |

| Customer Segment | Fleet operators (small and large size), shippers and aggregators in the UK |

| Customer Relationship | • External customers and their representatives are involved in the advisory group to understand expectations. • Internal customers’ needs are taken into account through interviews and workshops. |

| Channels | • Face-to-face workshops for initiation. • Digital platform for operation. • Regular meetings between partners and trustee to build trust and incentivise collaboration. • Communications through advisory group channels and DVV Media International (DVV) publications and events. |

| Key Activities 1 | • Identification of clusters among participants. • Legal and formal contract between partners. • Neutral trustee responsible for legal requirements for initiation of collaborations. • Negotiation among partners about workflow process and sharing revenue method that is defined in the contract agreement. • Operation management in terms of scheduling and routing done by the neutral trustee. • Neutral trustee to share the cost savings and revenues among partners following contract agreement. • Periodic review of collaboration performance. |

| Key Resources | • Shared assets (fleets, warehouses, equipment). • Human assets. • Digital platform with optimization algorithms. • Processes definition. |

| Key Partners | • TrackM8 acting as a neutral trustee. • Transport Systems Catapult. • Herriot Watt University. • DVV Media International. • World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD). |

| Revenue Streams | • Non-subscription fee. The FSL platform will use the savings and interest generated to pay for the operation of the platform and therefore the services of the neutral trustee. • Neutral trustee to share the cost savings among partners depending on the selected method based on game theory. |

| Cost Structure | • Operational cost (including marketing and sales). • Labour cost. • Digital platform maintenance. |

| Forms of Collaboration | • Centralised and decentralised depending on the stage of the collaborative process. • Multilateral. |

| Strategies of Collaboration | • Route scheduling/Planning. • Backhauling. • Freight exchange. • Consolidation centres. • Delivery and servicing plans. • Joint optimisation of assets. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vargas, A.; Patel, S.; Patel, D. Towards a Business Model Framework to Increase Collaboration in the Freight Industry. Logistics 2018, 2, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics2040022

Vargas A, Patel S, Patel D. Towards a Business Model Framework to Increase Collaboration in the Freight Industry. Logistics. 2018; 2(4):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics2040022

Chicago/Turabian StyleVargas, Alix, Shushma Patel, and Dilip Patel. 2018. "Towards a Business Model Framework to Increase Collaboration in the Freight Industry" Logistics 2, no. 4: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics2040022

APA StyleVargas, A., Patel, S., & Patel, D. (2018). Towards a Business Model Framework to Increase Collaboration in the Freight Industry. Logistics, 2(4), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics2040022