Design of a Remanufacturing Line Applying Lean Manufacturing and Supply Chain Strategies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Related Works

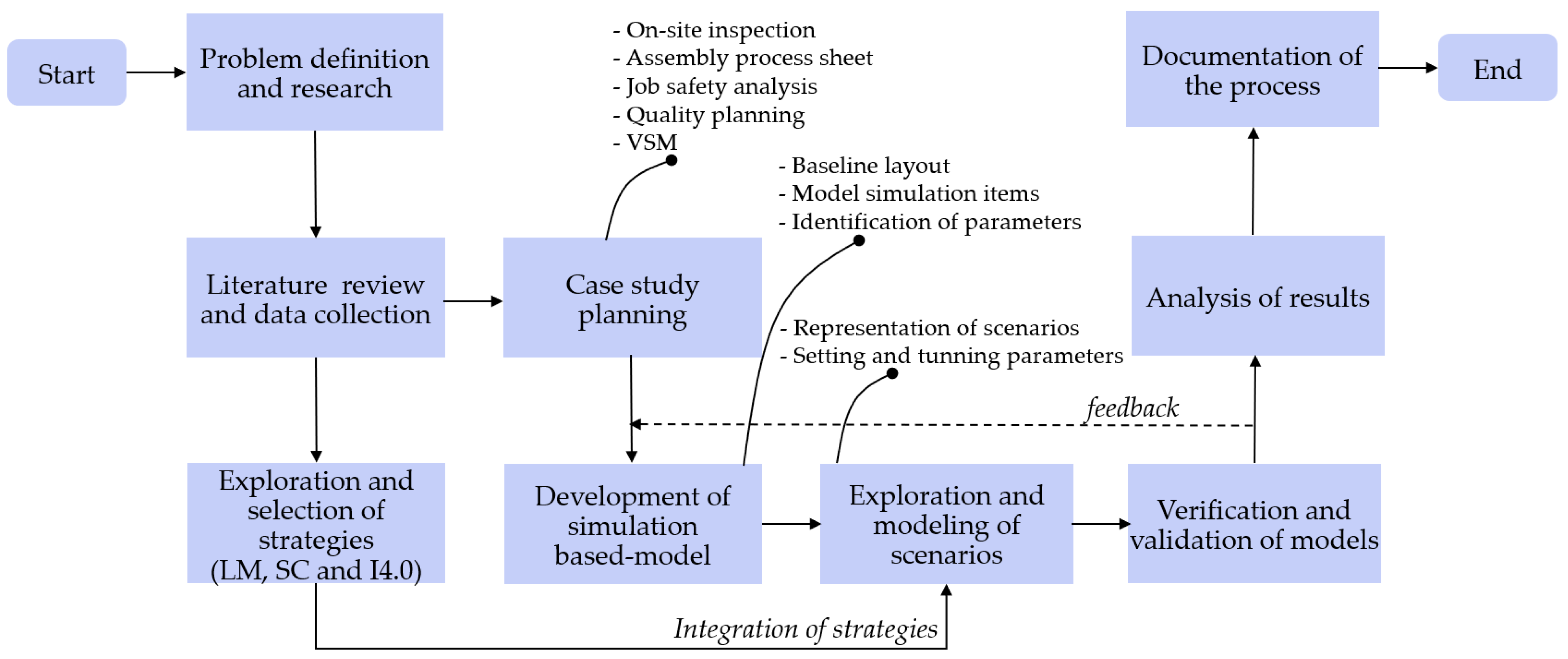

3. Material and Methods

- RQ1. Do LM, SC, and I4.0 strategies represented in DES models facilitate decision making?

- RQ2. How does integrating LM, SC, and I4.0 strategies into DES models support the design of a new remanufacturing line based on expected demands?

- RQ3. What are the outcomes of using LM and SC strategies with the support of I4.0 technologies to remanufacture engines?

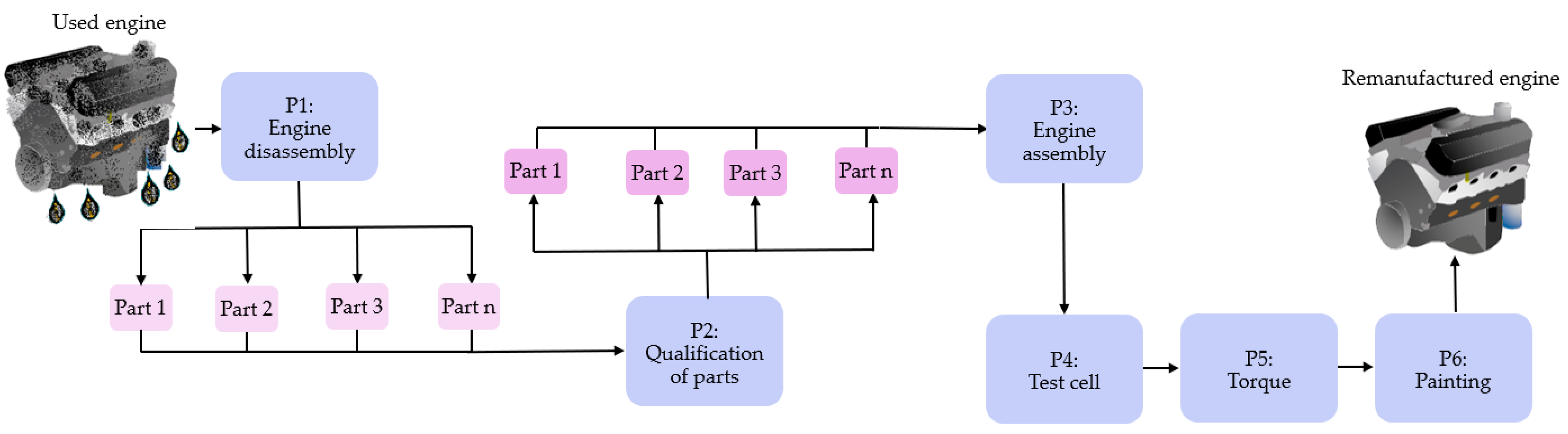

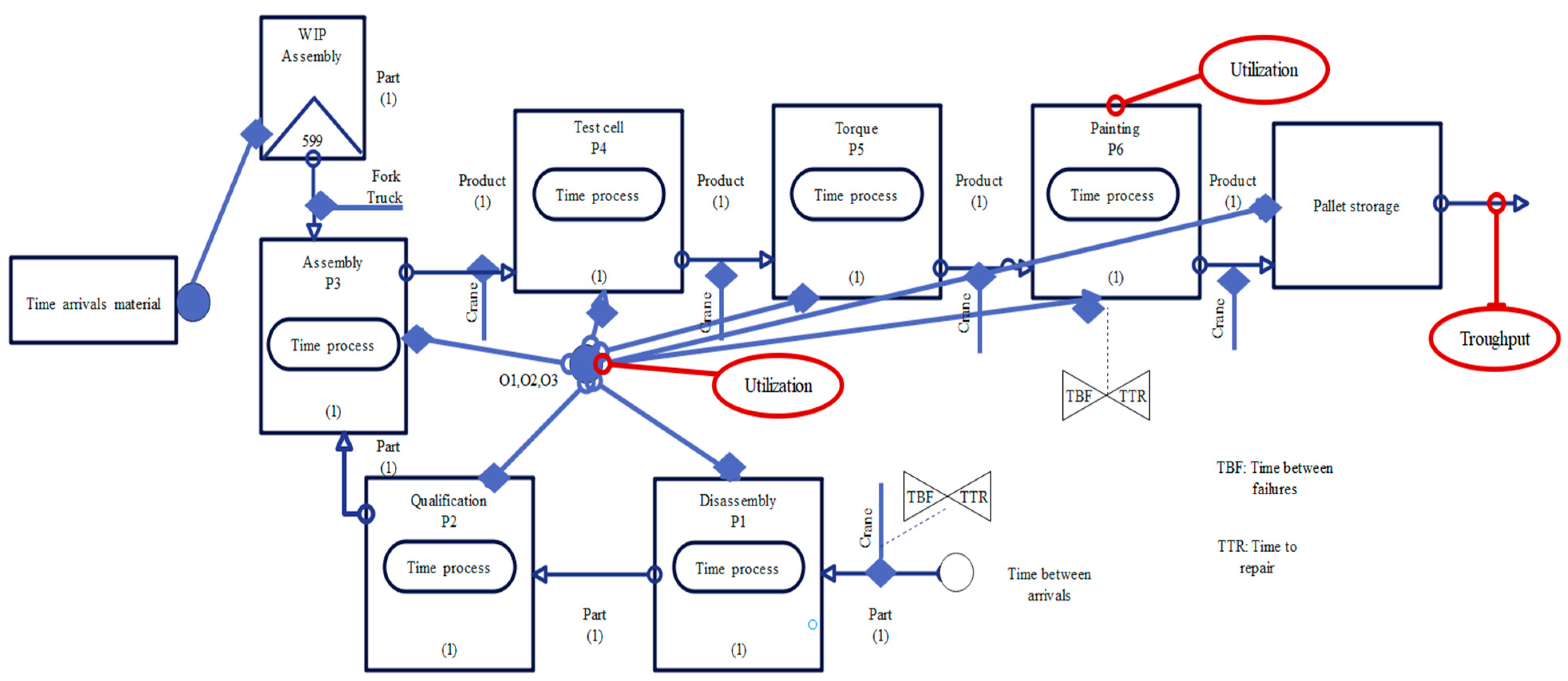

4. A Proof of Concept for a Remanufacturing Line Based on DES Scenarios

- P1.

- Engine disassembly. The parts are extracted and classified to be reused or reworked;

- P2.

- Qualification of parts. The parts are identified through the bill of materials (BOM) and selected for repair, recycling, and reuse using the critical to-quality tool;

- P3.

- Engine assembly. The desired transformation from the initial engine model to one that produces fewer CO2 emissions;

- P4.

- Test Cell. A series of tests to verify that the engine meets the quality standards;

- P5.

- Torque. The engine passes the process of bolt and screw tightening;

- P6.

- Painting. The engine is painted and packed as a final product.

5. Results

5.1. Statistics of the Simulation Models by Scenario

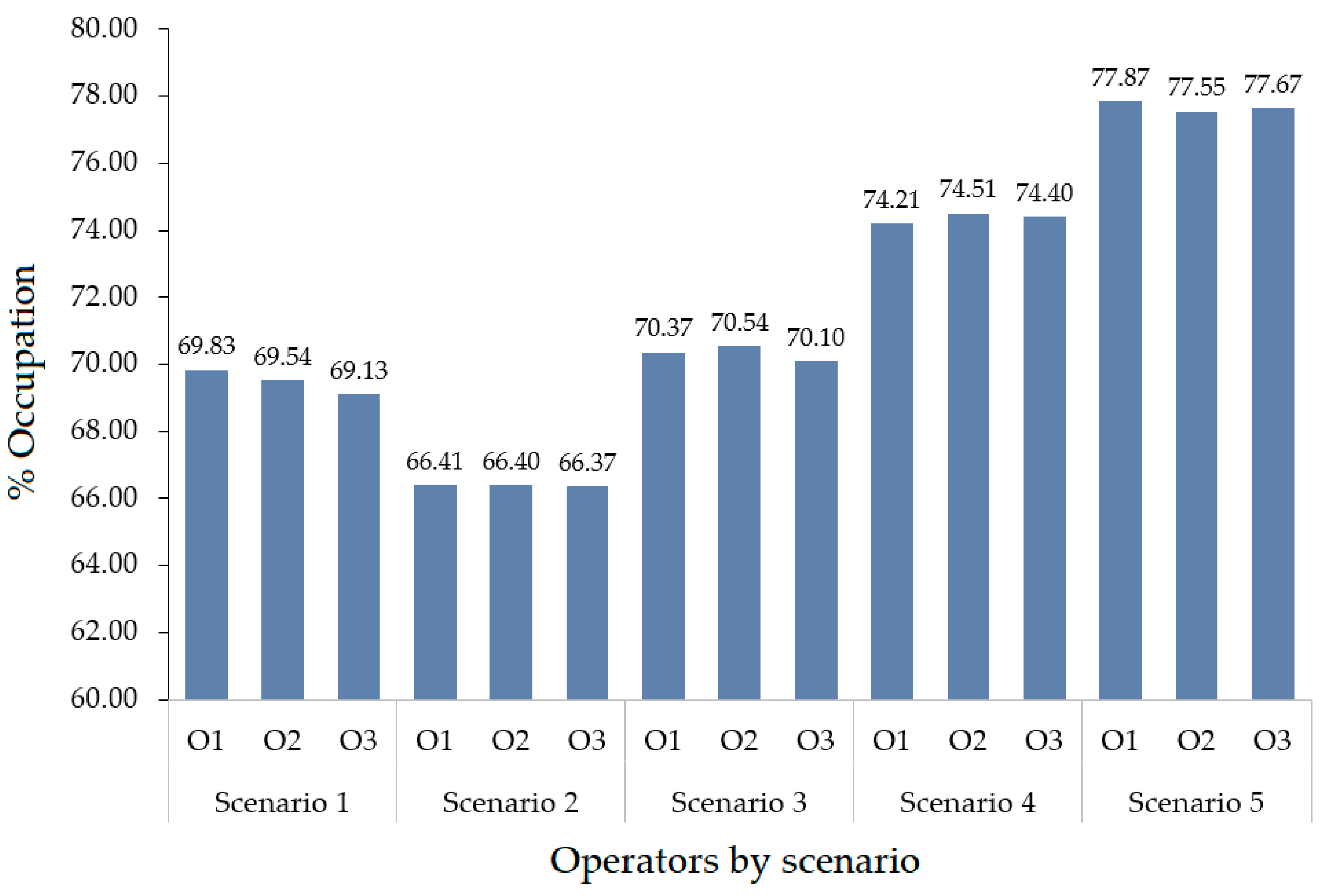

5.2. Statistics by Percentage of Time Process and Human Labor

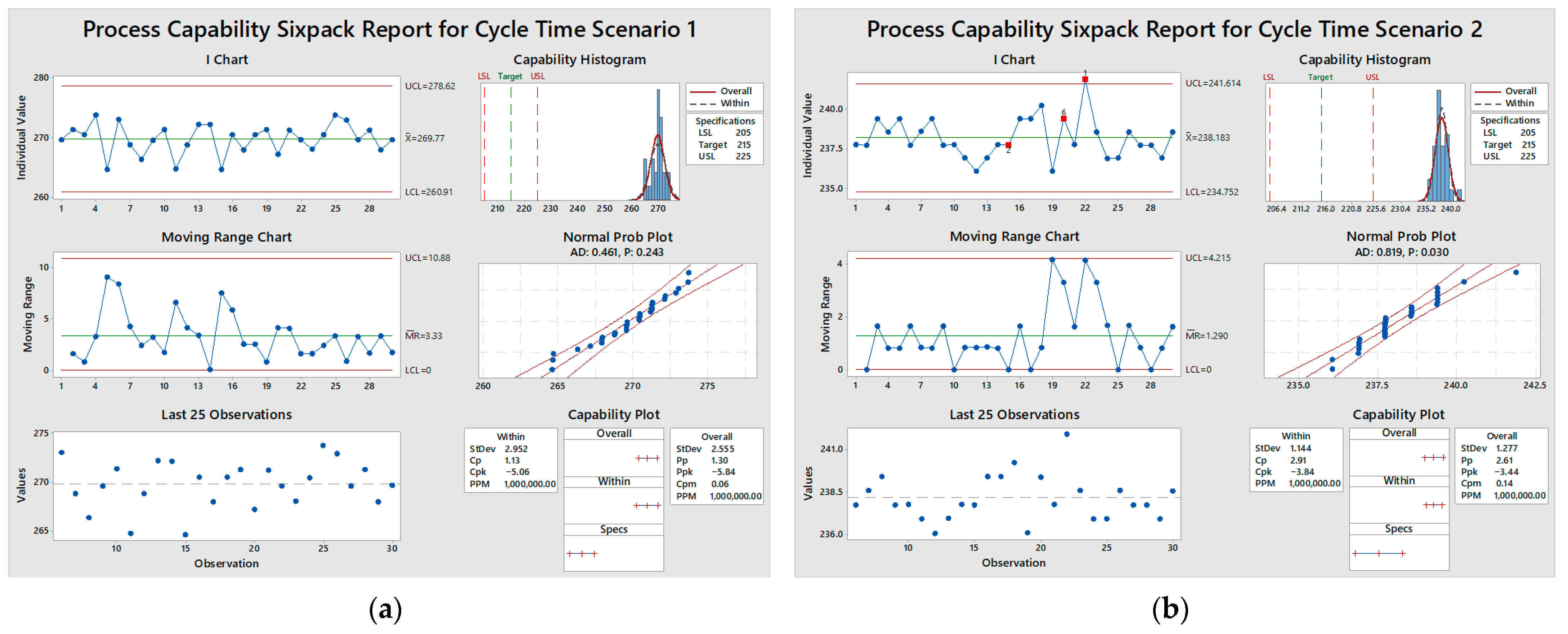

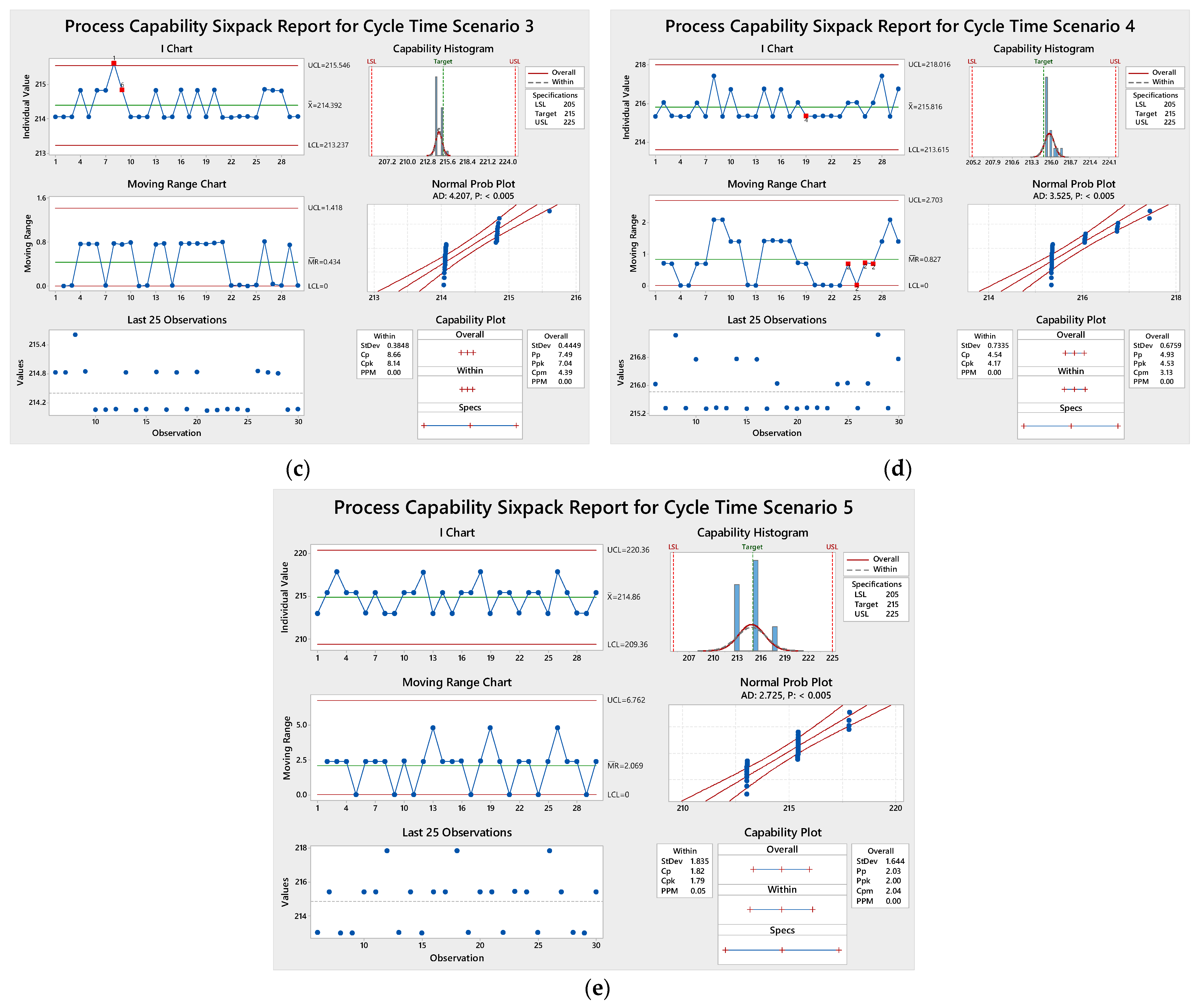

5.3. Process Capability Report by Scenario

| Scenario | % ATML | % ATW | % ATP | % ATB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 33.39 | 17.51 | 46.52 | 2.58 |

| 2 | 43.76 | 2.92 | 51.87 | 1.45 |

| 3 | 38.34 | 1.63 | 57.31 | 2.72 |

| 4 | 40.72 | 1.82 | 53.30 | 4.16 |

| 5 | 42.01 | 1.54 | 53.66 | 2.79 |

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lothary, D.; Tomov, P.; Dimitrov, L. Combination of an ERP System with Other Technological Approaches to Increase Sustainability in Discrete Manufacturing. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electronics, Engineering Physics and Earth Science, Kavala, Greece, 21–23 June 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlewski, P. Scientific and Practical Challenges for the Development of a New Approach to the Simulation of Remanufacturing. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.; Reinhart, G. Towards the integration of remanufacturing into existing manufacturing systems. Procedia CIRP 2024, 130, 1447–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekara, H.; Gamage, J.; Punchihewa, H. Remanufacture for sustainability: Barriers and solutions to promote automotive remanufacturing. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 43, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wabtec Corporation. Revolutionizing the Way the World Moves for Future Generations. In 2023 Sustainability Report. Available online: https://www.wabteccorp.com/sustainability (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Boorsma, N.; Peck, D.; Bakker, T.; Bakker, C.; Balkenende, R. The strategic value of design for remanufacturing: A case study of professional imaging equipment. J. Remanuf. 2022, 12, 187–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corum, A. Remanufacturing: A Case Study in Mercedes-Benz Bus Factory. In Proceedings of the 12th Annual International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Istanbul, Turkey, 7–10 March 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crotti, G. Review and new horizons of Facility Layout Planning. Master’s Thesis, Politecnico di Milano, Milan, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Goodall, P.; Sharpe, R.; West, A. A data-driven simulation to support remanufacturing operations. Comput. Ind. 2019, 105, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, A.S.; Kim, H.; Sivakumar, P.K.; Liu, Z.C.; Zhang, H.C. Life Cycle Assessment: A Comparison of Manufacturing and ReManufacturing Processes of a Diesel Engine. In Re-Engineering Manufacturing for Sustainability; Nee, A., Song, B., Ong, S.K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2013; pp. 675–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, E.L.S.; Tjahjono, B.; Beltran, M.; Julião, J. Demystifying the digital transition of remanufacturing: A systematic review of literature. Comput. Ind. 2022, 134, 103567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Soni, G.; Jabeen, F.; Tiwari, N.K.; Sariyer, G.; Ramtiyal, B. A hybrid Bayesian approach for assessment of industry 4.0 technologies towards achieving decarbonization in manufacturing industry. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 190, 110057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buer, S.V.; Semini, M.; Strandhagen, J.O.; Sgarbossa, F. The complementary effect of lean manufacturing and digitalisation on operational performance. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 1976–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahardjo, B.; Wang, F.-K.; Yeh, R.-H.; Chen, Y.-P. Lean manufacturing in industry 4.0: A smart and sustainable manufacturing system. Machines 2023, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palange, A.; Dhatrak, P. Lean manufacturing a vital tool to enhance productivity in manufacturing. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejsmont, K.; Gladysz, B.; Corti, D.; Castaño, F.; Mohammed, W.M.; Martinez Lastra, J.L. Towards ‘Lean Industry 4.0’—Current trends and future perspectives. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1781995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillinger, F.; Tropschuh, B.; Dervis, M.Y.; Reinhart, G. A systematic approach to identify the interdependencies of lean production and Industry 4.0 elements. Procedia CIRP 2022, 112, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, A. Introduction to the Supply Chain Concept. In Supply Chain: Fundamentals and Best Practices to Compete by Leveraging the Network, 1st ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudouaia, M.A.; Ouchani, S.; Qaisar, S.M.; Almaktoom, A.T. Supply Chain 5.0: Vision, Challenges, and Perspectives. In Proceedings of the 21st Learning and Technology Conference, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 15–16 January 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Figliè, R.; Amadio, R.; Tyrovolas, M.; Stylios, C.; Paśko, Ł.; Stadnicka, D.; Carreras-Coch, A.; Zaballos, A.; Navarro, J.; Mazzei, D. Towards a taxonomy of industrial challenges and enabling technologies in industry 4.0. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 19355–19374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giovanni, P.; Cariola, A. Process innovation through industry 4.0 technologies, lean practices and green supply chains. Res. Transp. Econ. 2021, 90, 100869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Merino, M.; Maqueira-Marín, J.M.; Moyano-Fuentes, J.; Castaño-Moraga, C.A. Industry 4.0 and supply chain. A systematic science mapping analysis. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 181, 121788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, J.; Mula, J.; Díaz-Madroñero, M. Development of a conceptual model for lean supply chain planning in industry 4.0: Multidimensional analysis for operations management. Prod. Plann. Control 2023, 34, 1209–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugos, M.H. Essentials of Supply Chain Management, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Mourtzis, D. Simulation in the design and operation of manufacturing systems: State of the art and new trends. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 1927–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Hongbo, S.; Li, Y.; Akhtar, F.; Imran, A. A survey on VV&A of large-scale simulations. Int. J. Crowd Sci. 2019, 3, 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, F.M.; Saleh, M.; Al-Ahmari, A.M.; Anwar, S. The impact of industry 4.0 technologies on manufacturing strategies: Proposition of technology-integrated selection. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 21574–21583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tania, R.; Josefa, M.; Raquel, S. Quantitative modelling approaches for lean manufacturing under uncertainty. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 5989–6015. [Google Scholar]

- Dikhanbayeva, D.; Tokbergenova, A.; Lukhmanov, Y.; Shehab, E.; Pastuszak, Z.; Turkyilmaz, A. Critical factors of industry 4.0 implementation in an emerging country: Empirical study. Future Internet 2021, 13, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolgui, A.; Ivanov, D. 5G in digital supply chain and operations management: Fostering flexibility, end-to-end connectivity and real-time visibility through internet-of-everything. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 60, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, B.; Hernández, X.F.; Jané, N.A. Combining lean and agile manufacturing competitive advantages through industry 4.0 technologies: An integrative approach. Prod. Plann. Control 2021, 34, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raji, I.O.; Shevtshenko, E.; Rossi, T.; Strozzi, F. Modelling the relationship of digital technologies with lean and agile strategies. Supply Chain Forum Int. J. 2021, 22, 323–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, S.; Dai, S.; Jiang, Z.; Gong, Q.; Wang, Y. Optimization of third party take-back enterprise collection strategy based on blockchain and remanufacturing reverse logistics. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 187, 109846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guchhait, R.; Sarkar, B. Economic evaluation of an outsourced fourth-party logistics (4PL) under a flexible production system. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2025, 279, 109440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guchhait, R.; Sarkar, M.; Sarkar, B.; Yang, L.; AlArjani, A.; Mandal, B. Extended material requirement planning (MRP) within a hybrid energy-enabled smart production system. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2024, 42, 100717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, B.; Bhuniya, S. A sustainable flexible manufacturing–remanufacturing model with improved service and green investment under variable demand. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 202, 117154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, B.K.; Pareek, S.; Tayyab, M.; Sarkar, B. Autonomation policy to control work-in-process inventory in a smart production system. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 1258–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midilli, Y.E.; Elevli, B. Value stream mapping with simulation to optimize stock levels: Case study. Jordan J. Mech. Ind. Eng. 2020, 14, 295–302. [Google Scholar]

- Pekarcikova, M.; Trebuna, P.; Kliment, M.; Schmacher, B.A.K. Milk run testing through tecnomatix plant simulation software. Int. J. Simul. Modell. 2022, 21, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trebuna, P.; Pekarcikova, M.; Edl, M. Digital value stream mapping using the tecnomatix plant simulation software. Int. J. Simul. Modell. 2019, 18, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksar, O.; Elgun, D.; Beldek, T.; Konyalioglu, A.K.; Camgöz-Akdag, H. An integrated value stream mapping and simulation approach for a production line: A Turkish automotive industry case. In Digitizing Production Systems, LNME; Durakbasa, N.M., Gençyılmaz, M.G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afy-Shararah, M.; Salonitis, K. Integrated modeling of “soft” and “hard” variables in manufacturing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 122, 4259–4265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Possik, J.; Zouggar-Amrani, A.; Vallespir, B.; Zacharewicz, G. Lean techniques impact evaluation methodology based on a co-simulation framework for manufacturing systems. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2022, 35, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, P.; Ahmad, R. Quantifying the impact of inspection processes on production lines through stochastic discrete-event simulation modeling. Modelling 2021, 2, 406–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewska, K. Comparative simulation of the production flow with the implementation of Kanban and DBR. Manag. Prod. Eng. Rev. 2023, 14, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Rahman, M.S.; Mohamad, E.; Abdul Rahman, A.A. Enhancement of overall equipment effectiveness (OEE) data by using simulation as decision making tools for line balancing. Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2020, 18, 1040–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paula Ferreira, W.; Armellini, F.; de Santa-Eulalia, L.A.; Thomasset-Laperrière, V. Extending the lean value stream mapping to the context of Industry 4.0: An agent-based technology approach. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 63, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdiraji, H.A.; Yaftiyan, F.; Abbasi-Kamardi, A.; Garza-Reyes, J.A. Investigating potential interventions on disruptive impacts of industry 4.0 technologies in circular supply chains: Evidence from SMEs of an emerging economy. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 174, 108753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, C.G.; Winroth, M.P.; Ribeiro da Silva, E.H.D. Sustainable manufacturing in industry 4.0: An emerging research agenda. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 58, 1462–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, R.P.; Rab, S.; Suman, R.; Khan, S. Exploring relationships between lean 4.0 and manufacturing industry. Ind. Robot 2022, 49, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korchagin, A.; Deniskin, Y.; Pocebneva, I.; Vasilyeva, O. Lean maintenance 4.0: Implementation for aviation industry. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 63, 1521–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, M.R.; Ahmed, F.; Deb, A.K.; Chowdhury, M. Identifying barriers for implementing green supply chain management (GSCM) in footwear industry of Bangladesh: A Delphi study approach. Leather Footwear J. 2018, 18, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contini, G.; Grandi, F.; Peruzzini, M. A framework to enhance corporate sustainability in manufacturing through digital technologies and system thinking. In Advances in Transdisciplinary Engineering; Cooper, A., Trigos, F., Stjepandić, J., Curran, R., Lazar, I., Eds.; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattanaik, L.N. Simulation optimization of manufacturing takt time for a leagile supply chain with a de-coupling point. Int. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2021, 12, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurbuz, M.C.; Yurt, O.; Ozdemir, S.; Sena, V.; Yu, W. Global supply chains risks and COVID-19: Supply chain structure as a mitigating strategy for small and medium-sized enterprises. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 155, 113407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, D. Modeling and simulation of a multi-agent green supply chain management system for retailers. J. Eur. Des Systemes Automatises 2020, 53, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, W.; Nedelko, Z. Global sourcing strategies: A framework for lean, agile, and leagile. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, G.; Kumar, A.; Luthra, S.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Kumar, V.; Batista, L. A framework to achieve sustainability in manufacturing organisations of developing economies using industry 4.0 technologies’ enablers. Comput. Ind. 2020, 122, 103280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abideen, A.Z.; Sundram, V.P.K.; Pyeman, J.; Othman, A.K.; Sorooshian, S. Digital twin integrated reinforced learning in supply chain and logistics. Logistics 2021, 5, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, F.; Dallasega, P. Industry 4.0 concepts and lean methods mitigating traditional losses in engineer-to-order manufacturing with subsequent assembly on-site: A framework. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 51, 1363–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiryagin, M.; Wu, Q.; Polach, O.; Thorburn, J.; Chua, W.; Spiryagin, V.; Stichel, S.; Shrestha, S.; Bernal, E.; Ahmad, S.; et al. Problems, assumptions and solutions in locomotive design, traction and operational studies. Rail. Eng. Science 2022, 30, 265–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniyan, I.; Mpofu, K.; Ramatsetse, B.; Zeferino, E.; Monzambe, G.; Sekano, E. Design and simulation of a flexible manufacturing system for manufacturing operations of railcar subassemblies. Procedia Manuf. 2021, 54, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricondo, I.; Porto, A.; Ugarte, M. A digital twin framework for the simulation and optimization of production systems. Procedia CIRP 2021, 104, 762–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnanini, M.C.; Tolio, T.A.M. A model-based digital twin to support responsive manufacturing systems. CIRP Annals 2021, 70, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebrecht, C.; Kandler, M.; Lang, M.; Schaumann, S.; Stricker, N.; Wuest, T.; Lanza, G. Decision support for the implementation of industry 4.0 methods: Toolbox, assessment and implementation sequences for industry 4.0. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 58, 412–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ProModel. Available online: https://www.promodel.com/products/learnpromodel (accessed on 28 June 2024).

- Minitab, Statistical Software. Available online: https://www.minitab.com/en-us/products/minitab/ (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Geer Mountain, Statistically Fit Software. Available online: https://www.mcssl.com/store/geermountainsoftwarecorp/statfit-student-version-3121Sd (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Wondershare, EdrawMax. Available online: https://www.edrawsoft.com/edraw-max/ (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Greenwood, A.G.; Pawlewski, P.; Bocewicz, G. A conceptual design tool to facilitate simulation model development: Object flow diagram. In Proceedings of the Winter Simulation Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 8–11 December 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J.; Carson II, J.S.; Nelson, B.L.; Nicol, D.M. Discrete-Event System Simulation, 5th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2013; pp. 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Agostinho Jr, V.; Baldo, C.R. Assessment of the impact of industry 4.0 on the skills of lean professionals. Procedia Cirp 2021, 96, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeuf, A.; Pellerin, R.; Lamouri, S.; Tamayo-Giraldo, S.; Barbaray, R. The industrial management of SMEs in the era of industry 4.0. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 1118–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sony, M.; Naik, S. Critical factors for the successful implementation of industry 4.0: A review and future research direction. Prod. Plann. Control 2020, 31, 799–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, A.; Ali, A.A.; Nazam, M.; Nazim, M. Developing an interplay among the psychological barriers for the adoption of industry 4.0 phenomenon. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaloul, W.S.; Liew, M.S.; Zawawi, N.A.W.A.; Kennedy, I.B. Industrial revolution 4.0 in the construction industry: Challenges and opportunities for stakeholders. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2020, 11, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Singh, R.K.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Application of industry 4.0 technologies in SMEs for ethical and sustainable operations: Analysis of challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 124063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikolski, M. Study of production scenarios with the use of simulation models. Procedia Eng. 2017, 182, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, V.; Chattopadhyaya, S.; Mukhopadhyay, A.K.; Sharma, S.; Li, C.; Di Bona, G. A Sustainable methodology using lean and smart manufacturing for the cleaner production of shop floor management in industry 4.0. Mathematics 2022, 10, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottalico, A. Automation processes in the port industry and union strategies: The case of Antwerp. New Global Stud. 2022, 16, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliosa, M.; Tortorella, G.; Ferreira, J.C.E. Industry 4.0 and lean manufacturing: A systematic literature review and future research directions. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2021, 32, 543–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioffi, R.; Travaglioni, M.; Piscitelli, G.; Petrillo, A.; Parmentola, A. Smart manufacturing systems and applied industrial technologies for a sustainable industry: A systematic literature review. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uriarte, A.G.; Ng, A.H.C.; Moris, M.U. Supporting the lean journey with simulation and optimization in the context of industry 4.0. Procedia Manuf. 2018, 25, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, L.; Araújo, A.; Ávila, P.; Castro, H.; Putnik, G. Evaluation of the relation between lean manufacturing, industry 4.0, and sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strategies | ||

|---|---|---|

| Lean Manufacturing | ||

| VSM: Midilli and Elevli [38], Pekarcikova et al. [39], Trebuna et al. [40], Aksar et al. [41], Afy-Shararah and Salonitis [42], Ferreira et al. [47], Javaid et al. [50], Schulze and Dallasega [60]. SMED: Possik et al. [43]. Kanban: Pekarcikova et al. [39], Trebuna et al. [40], Tomaszewska [45], Schulze and Dallasega [60]. JIT: Korchagin et al. [51], Pattanaik [54], Schulze and Dallasega [60]. OEE: Abd Rahman et al. [46]. TPM: Korchagin et al. [51], Schulze and Dallasega [60]. Poka Y.: Possik et al. [43], Korchagin et al. [51], Schulze and Dallasega [60]. DBR: Tomaszewska [45]. 5s: Possik et al. [43]. | ||

| Supply Chain | ||

| ERP: Abideen et al. [59], Ricondo et al. [63], Magnanini and Tolio [64]. GSCM: Machado et al. [49], Sarker et al. [52], Wei [56], Yadav et al. [58]. SM: Martinez and Ahmad [44], Machado et al. [49], Pattanaik [54], Gurbuz et al. [55], Rashad and Nedelko [57], Yadav et al. [58], Abideen et al. [59], Schulze and Dallasega [60]. Logistic: Pekarcikova et al. [39], Pattanaik [54], Gurbuz et al. [55], Wei [56], Rashad and Nedelko [57], Yadav et al. [58], Abideen et al. [59]. SMo: Machado et al. [49]. | ||

| Industry 4.0 | ||

| IoT: Machado et al. [49], Javaid et al. [50], Korchagin et al. [51], Yadav et al. [58], Abideen et al. [59], Schulze and Dallasega [60], Daniyan et al. [62], Ricondo et al. [63], Magnanini and Tolio [64]. BD: Mahdiraji et al. [48], Machado et al. [49], Korchagin et al. [51]. Robotics: Machado et al. [49], Schulze and Dallasega [60], Daniyan et al. [62]. CPS: Machado et al. [49], Yadav et al. [58]. AI: Yadav et al. [58], Abideen et al. [59]. DT: Abideen et al. [59], Ricondo et al. [63], Magnanini and Tolio [64]. AR/VR: Machado et al. [49], Korchagin et al. [51], Contini et al. [53], Schulze and Dallasega [60]. CC: Machado et al. [49], Schulze and Dallasega [60], Ricondo et al. [63]. | ||

| Observed Item | Description |

|---|---|

| Product | Transportation |

| Type of production | One piece flow |

| Number of basic operations | 6 |

| Remanufacturing line | Manual |

| Number of workers | 3 |

| Planned downtime | 30 min |

| Total working time | 480 min |

| Readiness IoT | Initial |

| Readiness LM | Initial |

| Readiness SC | Initial |

| KPIs | Throughput, cycle time (CT), human labor occupation |

| Notation | Decision Variables | Notation | Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTij | Cycle time for engine i at operation j (hours) | J | Total number of operations (P1–P6) |

| Uwj | Utilization of workstation j (percentage). | N | Total number of engines to be remanufactured |

| TTRj | Time to repair at operation j (hours) | Ok | Number of operators available (k=3) |

| TBFj | Time between failures for operation j (hours) | Tij | Processing time for engine i at operation j (hours) |

| Xij | Binary variable (1 if engine i is processed at operation j, 0 otherwise) | Pf | Probability of failure at operation j |

| Qi | Quality compliance of engine i (1 if meets standards, 0 otherwise) | Cj | Capacity of workstation j (units/hour) |

| Lh | Human labor occupation (percentage of total available labor) | T | Total available working time (hours per shift/day) |

| TP | Total throughput (engines remanufactured per time unit) | Storage location capacity (pallets). | |

| Q | Output Quality | λ1,λ2,λ3 | Weighting coefficients for the objective function |

| D | Marketing demand |

| Scenario | Description | Strategies LM, SC and I4.0 | Core Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Remanufacturing line initial conditions. A forklift hauls materials from the warehouse to stations, a crane transports engines, and a warehouse holds materials. | Basic model | - |

| 2 | Scenario 1, plus the change in the layout distribution that decreases the distance by 66% from P3 station to P2 and P4 to reduce personnel trips, CT, and throughput. | LM1: Layout redesign to reduce travel times in the process. | VSM, SD, LR |

| 3 | Scenario 2, plus the supply of SM type materials for a better disposition of the materials, using a forklift to station P3 reduces delivery time by 9.91%. | LM2: Reduction in operator down time. SC1: New arrangement of materials. | KA, SM |

| 4 | Scenario 3, plus the employment of MK ready to use at P3 station, previously checked BOM at P2, the materials are ordered and sent to continue the flow of a piece with KN systems. | LM3: Installation of material kits at the point of use. SC2: Order of materials by kit. | MK KN |

| 5 | Scenario 4, plus IoT for communication in the areas, exploiting CC, statistics, and information. A synchronization between P2 and the warehouse occurs for the arrival of the MK to P3. | I4.0: Integration of IoT and data in the cloud. | IoT, CC |

| Scenario | Strategies | VAT | NVAT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Throughput (Engines) | WIP (Components) | CT (h) | ATP (h) | ATML (h) | ATW (h) | ATB (h) | ||

| 1 | Basic model | 29.0 | 1.0 | 269.89 | 125.54 | 90.08 | 47.28 | 6.99 |

| 2 | LM1 | 29.0 | 1.0 | 238.41 | 123.65 | 104.33 | 6.69 | 3.46 |

| 3 | LM2, SC1 | 31.0 | 1.0 | 213.18 | 122.17 | 81.73 | 3.48 | 5.80 |

| 4 | LM3, SC2 | 34.4 | 0.0 | 216.12 | 115.18 | 88.01 | 3.94 | 8.99 |

| 5 | I4.0 | 40.0 | 0.0 | 214.45 | 115.06 | 90.11 | 3.30 | 5.99 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Félix-Jácquez, R.H.; Hernández-Uribe, Ó.; Cárdenas-Robledo, L.A.; Mora-Alvarez, Z.A. Design of a Remanufacturing Line Applying Lean Manufacturing and Supply Chain Strategies. Logistics 2025, 9, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics9010033

Félix-Jácquez RH, Hernández-Uribe Ó, Cárdenas-Robledo LA, Mora-Alvarez ZA. Design of a Remanufacturing Line Applying Lean Manufacturing and Supply Chain Strategies. Logistics. 2025; 9(1):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics9010033

Chicago/Turabian StyleFélix-Jácquez, Rosa Hilda, Óscar Hernández-Uribe, Leonor Adriana Cárdenas-Robledo, and Zaida Antonieta Mora-Alvarez. 2025. "Design of a Remanufacturing Line Applying Lean Manufacturing and Supply Chain Strategies" Logistics 9, no. 1: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics9010033

APA StyleFélix-Jácquez, R. H., Hernández-Uribe, Ó., Cárdenas-Robledo, L. A., & Mora-Alvarez, Z. A. (2025). Design of a Remanufacturing Line Applying Lean Manufacturing and Supply Chain Strategies. Logistics, 9(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics9010033