Effect of Axis Change on Shrinkage Rate of 3D-Printed Bioceramic Zirconia Fabricated via Digital Light Processing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Groups

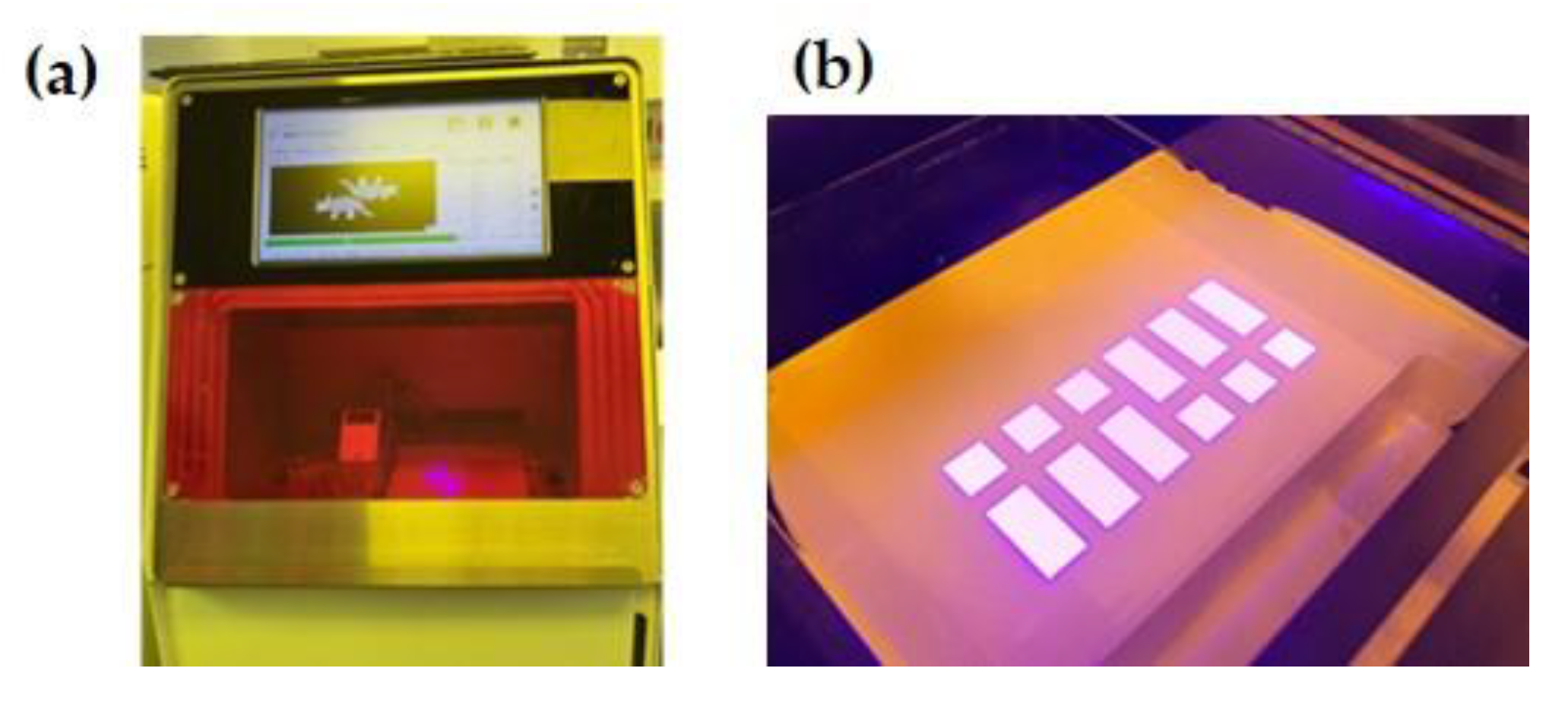

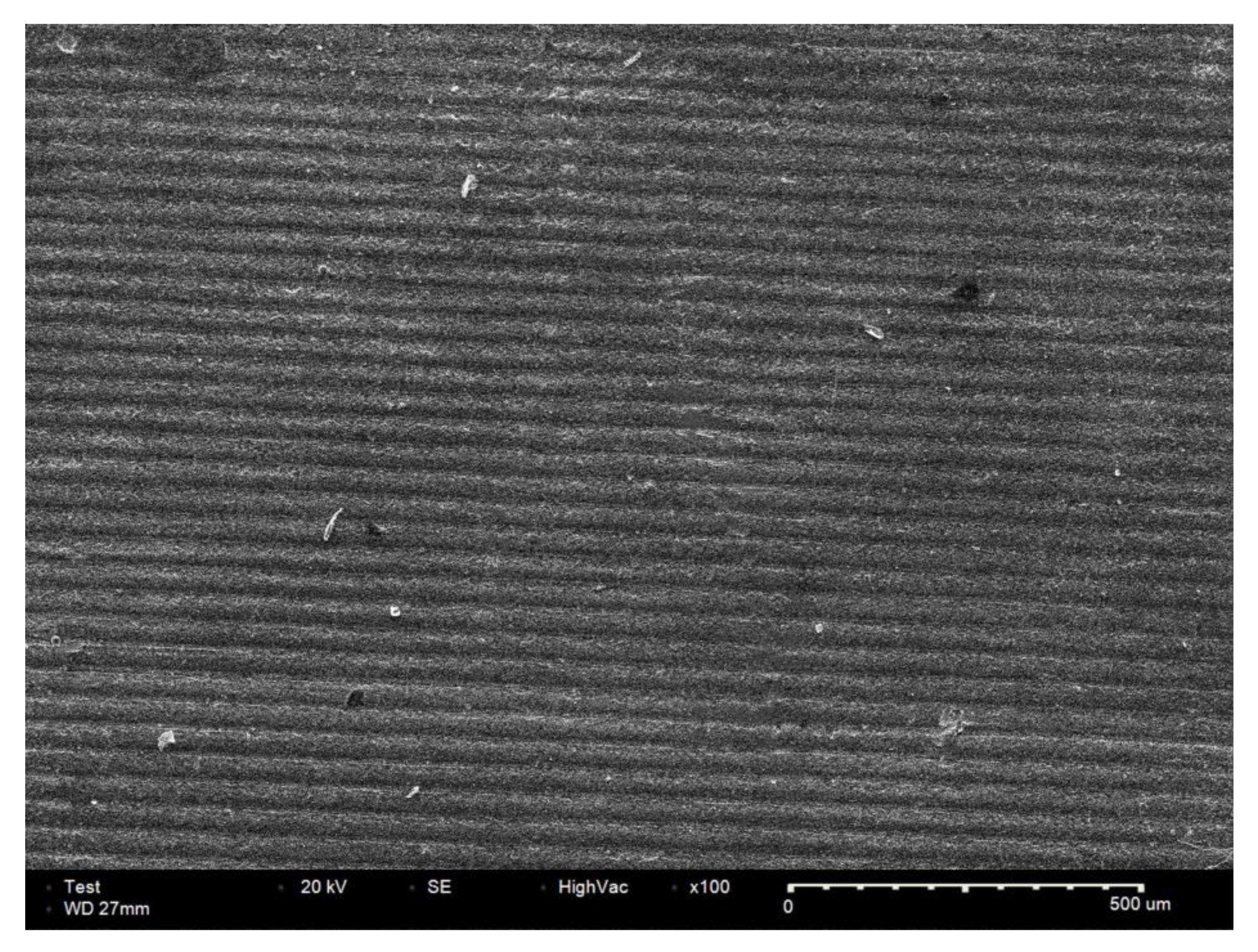

2.2. DLP Conditions

2.3. Axis Setting

2.4. Debinding and Sintering Schedule for 3D-Printed Specimens

2.5. Shrinkage Rate Evaluation

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

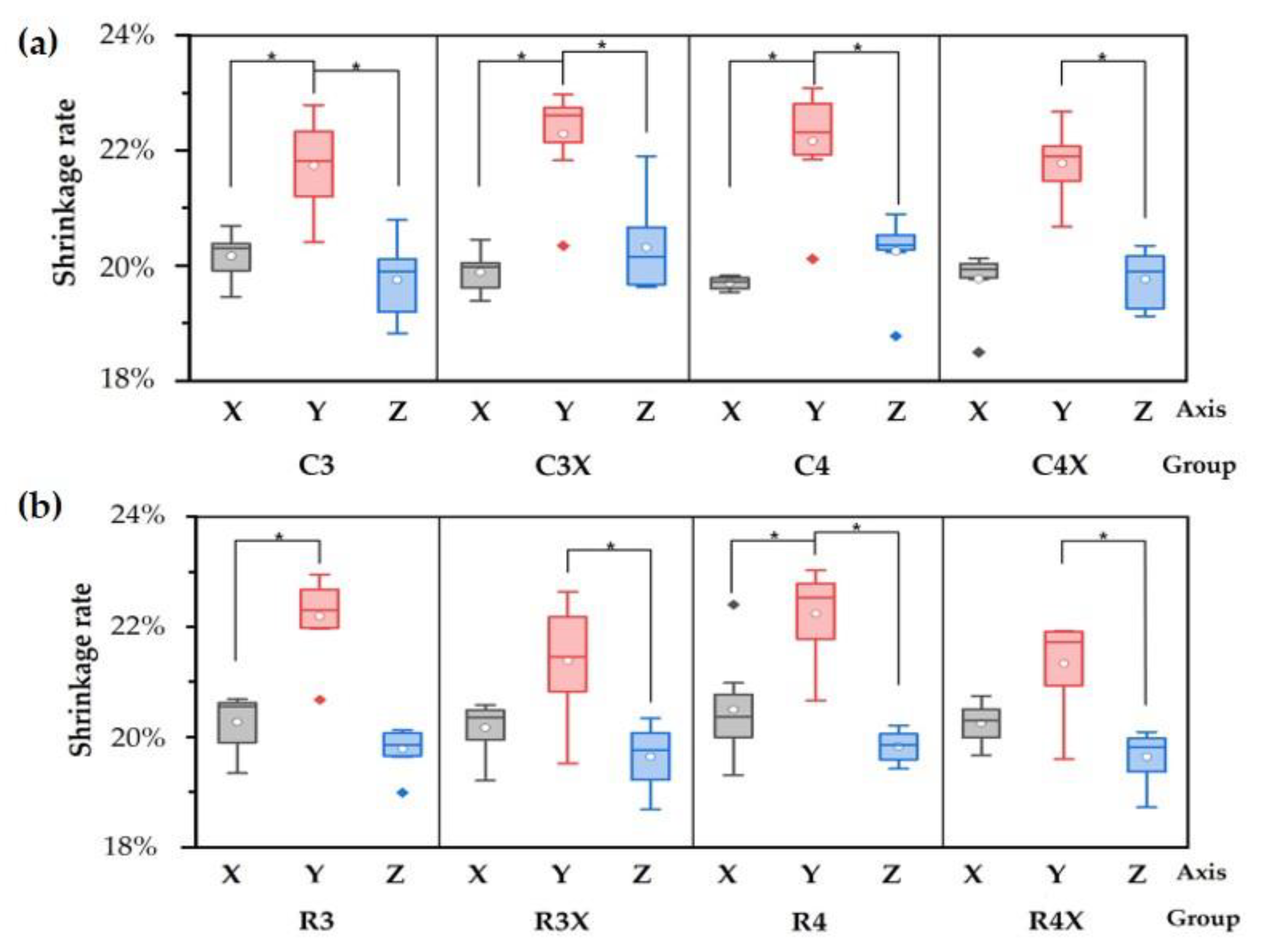

3.1. Shrinkage Rate Evaluation Based on Manufacturing Method

3.2. Shrinkage Rate Evaluation Based on Axis Change at Different Pre-Sinter Temperatures

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAD/CAM | computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing |

| LSPS | laser scanning projection stereolithography |

| MPSL | mask projection stereolithography |

| TGA | thermogravimetric analysis |

| DLP | digital light processing |

| M | subtractive manufacturing process |

| C | cubic 3D-printed specimen |

| R | cuboidal 3D-printed specimen |

| STL | standard tessellation language |

| LCM | light-curing resin molding |

References

- Manicone, P.F.; Rossi Iommetti, P.; Raffaelli, L. An overview of zirconia ceramics: Basic properties and clinical applications. J. Dent. 2007, 35, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebon, N.; Tapie, L.; Duret, F.; Attal, J.P. Understanding dental CAD/CAM for restorations—Dental milling machines from a mechanical engineering viewpoint. Part B: Labside milling machines. Int. J. Comput. Dent. 2016, 19, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Qiu, M.; Jiao, C.; Gu, J.; Xie, D.; Wang, C.; Tang, X.; Wei, Z.; Shen, L. Study on defect-free debinding green body of ceramic formed by DLP technology. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 2438–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Ramakrishna, S.; Singh, R. Material issues in additive manufacturing: A review. J. Manuf. Process. 2017, 25, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deckers, J.; Vleugels, J.; Kruthl, J.P. Additive Manufacturing of Ceramics: A Review. J. Ceram. Sci. Technol. 2014, 5, 245–260. [Google Scholar]

- Halloran, J.W. Ceramic Stereolithography: Additive Manufacturing for Ceramics by Photopolymerization. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2016, 46, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadkhah, M.; Tulliani, J.M.; Saboori, A.; Iuliano, L. Additive manufacturing of ceramics: Advances, challenges, and outlook. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2023, 43, 6635–6664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, C.; Lao, C.; Fu, Y.; Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, P.; He, Y. 3D printing of ceramics: A review. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2019, 39, 661–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.Q.; Lian, Q.; Li, D.C.; Jin, Z.M. Tilting separation analysis of bottom-up mask projection stereolithography based on cohesive zone model. J. Mater. Process. Tech. 2017, 243, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katal, G.; Tyagi, N.; Joshi, A. Digital light processing and its future applications. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2013, 3, 2250–3153. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Sun, J. Dimensional accuracy and clinical adaptation of ceramic crowns fabricated with the stereolithography technique. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2021, 125, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Yu, H.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Gao, B. Trueness analysis of zirconia crowns fabricated with 3-dimensional printing. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2019, 121, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truxova, V.; Safka, J.; Seidl, M.; Kovalenko, I.; Volesky, L.; Ackermann, M. Ceramic 3D printing: Comparison of SLA and DLP technologies. MM Sci. J. 2020, 3905–3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Liu, W.; Wu, Z.; An, D.; Huang, M.; Wu, H.; Jiang, Q.; Ji, X.; Wu, S.; Xie, Z. Fabrication of complex-shaped zirconia ceramic parts via a DLP-stereolithography-based 3D printing method. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 3412–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, M.; Lee, H.; Lee, W.; Kim, J.; Kim, J. Evaluation of Internal and Marginal Accuracy (Trueness and Precision) of Laminates Using DLP Printing and Milling Methods. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, M.; Kim, J. A Comparison of Internal, Marginal, and Incisal Gaps in Zirconia Laminates Fabricated Using Subtractive Manufacturing and 3D Printing Methods. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 728–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuer, F.; Schweiger, J.; Edelhoff, D. Digital dentistry: An overview of recent developments for CAD/CAM generated restorations. Br. Dent. J. 2008, 204, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanlar, L.N.; Rios, A.S.; Tahmaseb, A.; Zandinejad, A. Additive Manufacturing of Zirconia Ceramic and Its Application in Clinical Dentistry: A Review. Dent. J. 2021, 9, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Q.; Sui, W.; Wu, X.; Yang, F.; Yang, S. Additive manufacturing of ZrO2 ceramic dental bridges by stereolithography. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2018, 24, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, Y.; Hu, M.; Wang, Y.; Xv, Y.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Y. Strength and Adaptation of Stereolithography-Fabricated Zirconia Dental Crowns: An In Vitro Study. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2019, 32, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aduba, D.C., Jr.; Feller, K.D.; Williams, C.B. An investigation of build orientation on shrinkage in sintered bioceramic parts fabricated by vat photopolymerization. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA, 7–9 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zavaliangos, A.; Missiaen, J.M.; Bouvard, D. Anisotropy in shrinkage during sintering. Sci. Sinter. 2006, 38, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, I.O.; Suvaci, E.; Karademir, B.; Missiaen, J.M.; Carry, C.P.; Bouvard, D. Anisotropic sintering shrinkage in alumina ceramics containing oriented platelets. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2006, 89, 1972–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lame, O.; Bouvard, D.; Wiedemann, H. Anisotropic shrinkage and gravity induced creep during sintering of steel powder compacts. Powder Met. 2002, 45, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olevsky, E.A.; Kushnarev, B.; Maximenko, A.; Tikare, V.; Braginsky, M. Modelling of anisotropic sintering in crystalline ceramics. Philos. Mag. 2005, 85, 2123–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, H.X.; Mohanram, A.; Olevsky, E.; Bordia, R.K. Evolution of anisotropy in hierarchical porous ceramics during sinter-forging. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2016, 36, 2937–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, K.J.; Kang, J.H.; Fisher, J.G.; Park, S.W. Effect of the volume fraction of zirconia suspensions on the microstructure and physical properties of products produced by additive manufacturing. Dent. Mater. 2019, 35, e97–e106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klocke, F. Modern approaches for the production of ceramic components. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 1997, 17, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travitzky, N.; Bonet, A.; Dermeik, B.; Fey, T.; Filbert-Demut, I.; Schlier, L.; Scholordt, T.; Greil, P. Additive manufacturing of ceramic-based materials. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2014, 16, 729–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, L.; Bienenstein, D.; Borlaf, M.; Graule, T. Effects of the Layer Height and Exposure Energy on the Lateral Resolution of Zirconia Parts Printed by Lithography-Based Additive Manufacturing. Materials 2020, 13, 1317–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, R.M. Theory of thermal debinding. Int. J. Powder Metall. 1987, 23, 237–245. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Binner, J.; Bai, J. 3D printing of zirconia via digital light processing: Optimization of slurry and debinding process. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 40, 5837–5844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, Q. Effect of zirconia content and particle size on the properties of 3D-printed alumina-based ceramic cores. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 104, 6015–6028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Dhara, S.; Wang, L. Green ceramic machining: A top-down approach for the rapid fabrication of complex-shaped ceramics. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2008, 28, 2109–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galante, R.; Figueiredo-Pina, C.G.; Serro, A.P. Additive manufacturing of ceramics for dental applications: A review. Dent. Mater. 2019, 35, 825–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Liu, Y.S.; Liu, Y.S.; Wang, J.; Zeng, Q.F.; Hu, K.H.; Lu, Z.G. Influence of Vacuum Debinding Temperature on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Three-Dimensional-Printed Alumina via Stereolithography. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 7, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crivello, J.V.; Reichmanis, E. Photopolymer Materials and Processes for Advanced Technologies. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 533–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Ahn, G.S.; Kim, D.S. Development of nano-and microscale composite 3D scaffolds using PPF/DEF-HA and micro-stereolithography. Microelectron. Eng. 2009, 86, 1465–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanhui, L.; Yong, C.; Minglang, W. The cure performance of modified ZrO2 coated by paraffin via projection based stereolithography. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 4084–4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wang, F.; Yan, K. Micro-stereolithography of KNN-based lead-free piezoceramics. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 4880–4885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitteramskogler, G.; Gmeiner, R.; Felzmann, R.; Gruber, S.; Hofstetter, C.; Stampfl, J.; Ebert, J.; Wachter, W.; Laubersheimer, J. Light curing strategies for lithography-based additive manufacturing of customized ceramics. Addit. Manuf. 2014, 1, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Groups | Fabrication Method | Specimen Shape | Pre-Sinter Temperature (°C) | Axis Change | Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MC | Milling | Cube | No | 8 | |

| MR | Cuboid | No | 8 | ||

| C3 | 3D printing | Cube | 1300 | No | 8 |

| C3X | Yes | 8 | |||

| C4 | 1400 | No | 8 | ||

| C4X | Yes | 8 | |||

| R3 | Cuboid | 1300 | No | 8 | |

| R3X | Yes | 8 | |||

| R4 | 1400 | No | 8 | ||

| R4X | Yes | 8 |

| Zirconia | Acrylate | Photoinitiator | Dispersant | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBA | HDDA | PNPGDA | (Irgacure819) | (BYK-180) | ||

| 49.00 | 36.84 | 0.15 | 14.01 | 100 | ||

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Light direction | Top down |

| Energy source | 385–400 nm |

| Layer thickness | 50 μm |

| Exposure time per layer | 10 s |

| Light intensity | 110 mW/cm2 |

| Z-axis lift distance | 0.05 mm |

| Z-axis lift speed | 0.4 mm/m |

| Blade distance | 160 mm |

| Blade speed | 10 mm/m |

| Temperature (°C) | Rate (°C/min) | Holding Time (h:min) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Debinding | 230 | 0.5 | 1:00 |

| 380 | 0.5 | 2:00 | |

| 600 | 0.5 | 1:00 | |

| Pre-sintering | 1040 | 1.0 | 1:00 |

| 1300/1400 | 5.0 | 1:00 | |

| Final sintering | 25 | 10.0 | 0:00 |

| 600 | 10.0 | 0:30 | |

| 1000 | 10.0 | 1:00 | |

| 1300/1400 | 10.0 | 0:30 | |

| 1500 | 5.0 | 2:00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, J.-Y.; Jung, Y.-N.; Jang, K.-J.; Lee, S.-K.; Choi, S.-W.; Lee, Y.-S.; Yang, Y.P.; Yun, K.-D. Effect of Axis Change on Shrinkage Rate of 3D-Printed Bioceramic Zirconia Fabricated via Digital Light Processing. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10030140

Park J-Y, Jung Y-N, Jang K-J, Lee S-K, Choi S-W, Lee Y-S, Yang YP, Yun K-D. Effect of Axis Change on Shrinkage Rate of 3D-Printed Bioceramic Zirconia Fabricated via Digital Light Processing. Biomimetics. 2025; 10(3):140. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10030140

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Ju-Young, Yoo-Na Jung, Kyoung-Jun Jang, Sang-Kyu Lee, Seong-Won Choi, Yong-Seok Lee, Yunzhi Peter Yang, and Kwi-Dug Yun. 2025. "Effect of Axis Change on Shrinkage Rate of 3D-Printed Bioceramic Zirconia Fabricated via Digital Light Processing" Biomimetics 10, no. 3: 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10030140

APA StylePark, J.-Y., Jung, Y.-N., Jang, K.-J., Lee, S.-K., Choi, S.-W., Lee, Y.-S., Yang, Y. P., & Yun, K.-D. (2025). Effect of Axis Change on Shrinkage Rate of 3D-Printed Bioceramic Zirconia Fabricated via Digital Light Processing. Biomimetics, 10(3), 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics10030140