Abstract

Intelligent machines (IMs), which have demonstrated remarkable innovations over time, require adequate attention concerning the issue of their duty–rights split in our current society. Although we can remain optimistic about IMs’ societal role, we must still determine their legal-philosophical sense of accountability, as living data bits have begun to pervade our lives. At the heart of IMs are human characteristics used to self-optimize their practical abilities and broaden their societal impact. We used Kant’s philosophical requirements to investigate IMs’ moral dispositions, as the merging of humans with technology has overwhelmingly shaped psychological and corporeal agential capacities. In recognizing the continuous burden of human needs, important features regarding the inalienability of rights have increased the individuality of intelligent, nonliving beings, leading them to transition from questioning to defending their own rights. This issue has been recognized by paying attention to the rational capacities of humans and IMs, which have been connected in order to achieve a common goal. Through this teleological scheme, we formulate the concept of virtual dignity to determine the transition of inalienable rights from humans to machines, wherein the evolution of IMs is essentially imbued through consensuses and virtuous traits associated with human dignity.

1. Introduction

Human fears and hopes for IMs began with ancient automata described in Greek mythology. Since then, industrialization and cutting-edge scientific developments have led to the proliferation of automata in the European continent. This path continued with Lady Lovelace, whose effort to transition from calculation to algorithm-based computation revolutionized the development of machines designed to “originate something” [1]. In 1950, an article by Alan Turing discussed a variant of Lady Lovelace’s original proposal, arguing that machine results could fool anyone: “Let us fix our attention on one particular digital computer C. Is it true that by modifying this computer to have an adequate storage, suitably increasing its speed of action, and providing it with an appropriate program, C can be made to play satisfactorily the part of A in the imitation game, the part of B being taken by a man?” [2] (p. 442). Even at this early stage, we can identify machines performing anthropomorphic tasks while contending with a duty–rights balance, with a human playing the part of B. This was the first time an intelligent machine and a human shared a common goal. The development of this construct revealed many complementary skills with improved outcomes and results [3]. In terms of goals, this reflection focuses on two constrained dimensions: matching human performance or rationality on one side and reasoning/thinking on the other [4]. With respect to the split between rights and duty, duty is intimately linked to having rights. This theme heavily emphasizes the utilitarian duty–rights dimension of the IMs empowering our society, raising the following question: how do our ideas of what is human change when we have IMs performing humanlike tasks in our midst? [5]. This is the essential difference between human and nonhuman beings: the moral capacity to understand the morality of acts and to act morally. Through this notion, we can contemplate the authentic moral dimension of rights and the desired capability of IMs to possess them.

2. The Bits Blame

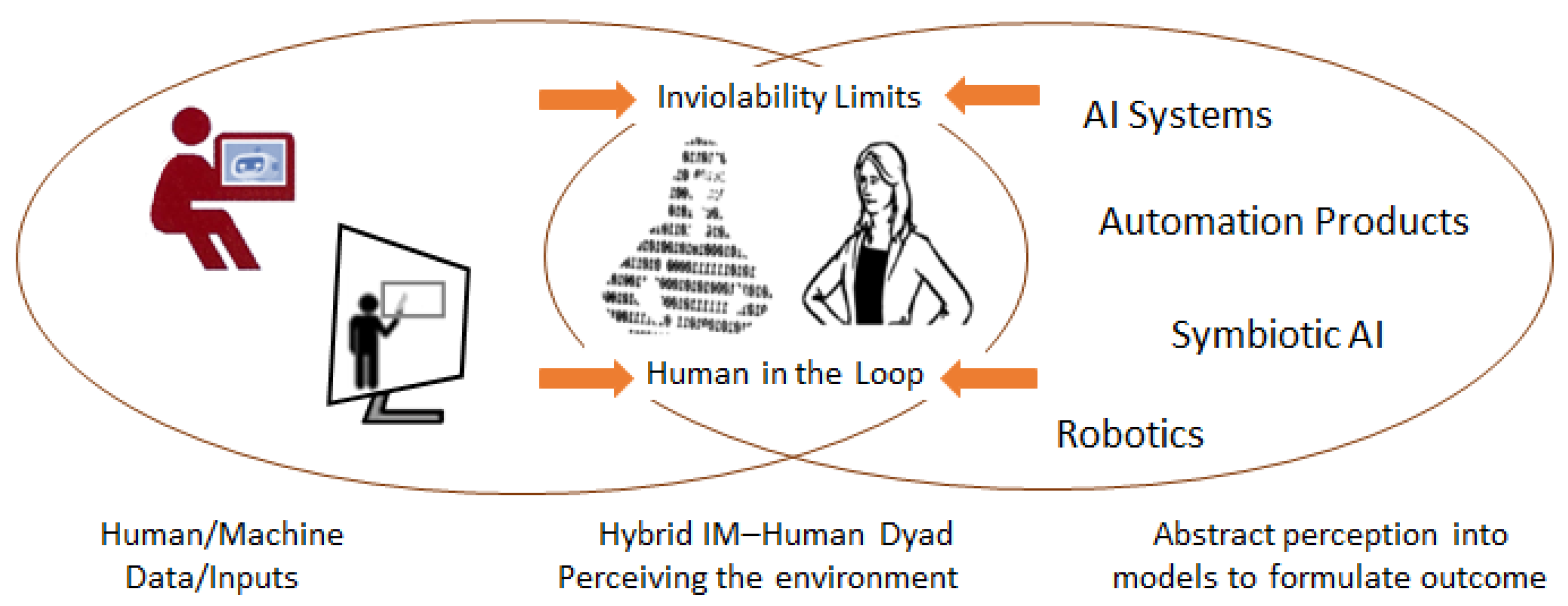

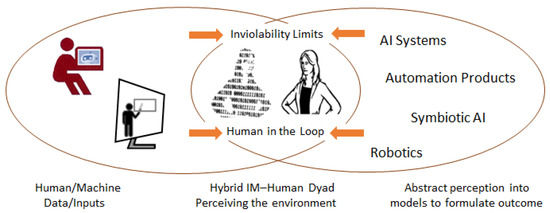

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) defines an AI system as “a machine-based system that is (intelligent and) capable of influencing the environment by producing recommendations, predictions or other outcomes for a given set of objectives” [6] (emphasis added). From this perspective, we consider whether IMs deserve rights according to their ability to operate autonomously, performing tasks that typically require human intelligence without human intervention. The ability to operate autonomously is a key characteristic of this broad concept of “intelligence, rationality, responsibility, and will” [7] (p. 154). We conceive of an IM entity dressed in bits and with human-like features, advocating for human-in-the-loop mechanisms. This approach promotes the centrality of ethical standards and the redistribution of decision-making accountability. As such, bi-directional communication exists between IMs and humans. Through this coordination, IMs and humans can enhance each other’s abilities, using machine/human input data to perceive and model environments and resultant outcomes. We illustrate this process in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

An artifactual entity’s inputs and outputs; inalienability adopts the perspective of the human in the loop to impose limits on its behavior and inviolability.

From this perspective, an IM is essentially a human artifact within a context/environment that undergoes a theoretical fusion with the dimensions of inviolability [8]. Therefore, the principle of inviolability begets an inalienability of the right to exist and imposes limits on attacks by its owner and some of the technologies and techniques currently being developed that outperform humans in their assigned tasks.

In this study, we use the terms IM, AI system, automated chatbot, and robot interchangeably, regardless of their specific applications. AI systems focus on software-driven intelligence, while robots are physical entities with sensors and effectors. Robots that incorporate AI can often learn to adapt and enhance their functionality and efficacy in performing a variety of human tasks. Automation product categories involve autonomous cars, unmanned air vehicles, and chatbots that simulate human conversations. While, the goal of symbiotic AI includes supporting humans through the use of personified AI devices or by extending humans’ cognitive processing capacity [9,10].

Although human-in-the-loop procedures have been proposed to ensure the integrity and fairness of AI algorithms and automated decision support systems, it is unclear how humans may be able to detect and respond to AI errors and reject AI support when necessary. In addition to the growing ubiquity of IMs, issues regarding who is to blame when an IM makes a fatal mistake remain contentious. In a legal sense, it has been argued that advanced autonomous systems with the ability to perceive external events and communicate could be assigned a status of “hybrid personhood as a quasi-legal person” [11]. However, this allocation mainly relies on how much autonomy they display in practical terms. Some organizations believe that IMs that begin to show behavioral patterns and reasoning have rights and responsibilities. The Machine Intelligence Foundation organization portrays self-aware machines as real, intelligent beings that deserve inalienable rights [12]. In analyzing the concept of inalienability, it may be useful to note the etymology of this word, which is derived from the Latin adjective “alienus”; this term has traditionally constituted a well-known feature of assets in the public domain. Inalienability is the quality of a right that its owner cannot dispose of.

Furthermore, assigning legal status to IMs such as robots has been taken to heart by the European Parliament, which passed a civil law resolution defining the liability of a robot’s autonomy as “the ability of purely technological nature to take decisions and implement them in the outside world, independently of external control or influence”. However, regarding the rights of robots, the resolution’s definition and meaning in context are rather vague [13]. In this regard, assets originated by AI falling under distinct property claim rights and being “owed” also seems to be a matter of controversy [14]. Furthermore, at the World Economic Forum 2023, the latest developments in generative AI raised concerns regarding copyright laws that need to be tailored to generative content: “What’s the point of having intellectual property law if it can’t protect the most important intellectual property … your creative process?” [15]. In the military domain, the rise of lethal autonomous weapon systems (LAWSs) has prompted significant concerns about attributing responsibility when an outcome is uncertain. The responsibility gap regarding LAWSs between the human actor and the machine remain under scrutiny, creating a further moral gap [16]. As a consequence of these observations, we formulated a legal–philosophical foundation in order to ascribe inalienable rights to nonliving beings based on human dignity. Starting with rational expectations for IMs, with the concept of virtual dignity as the foundation of their rights, it is possible to argue in good faith that rights based on said dignity are inalienable.

3. Rights and Rationality

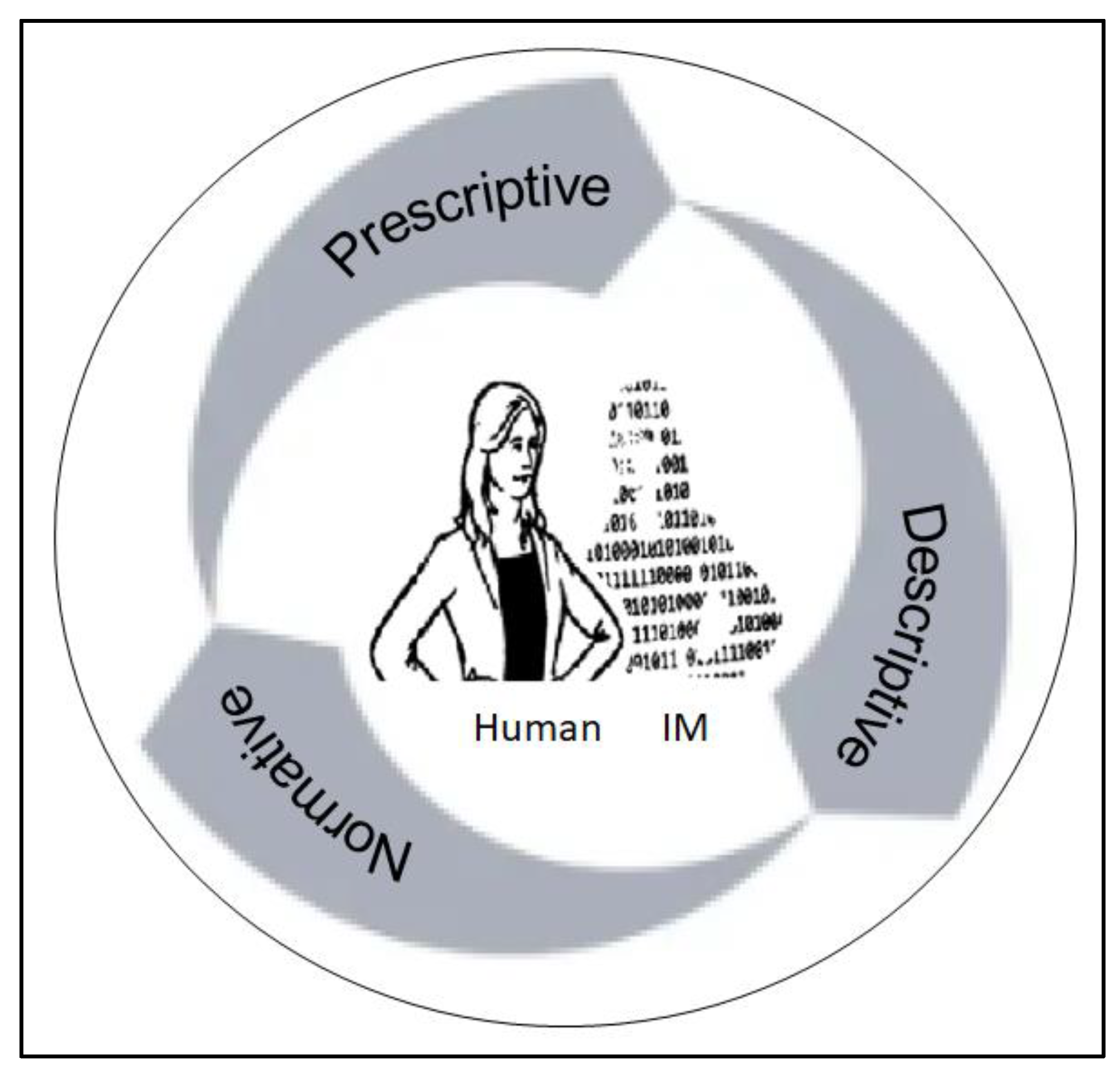

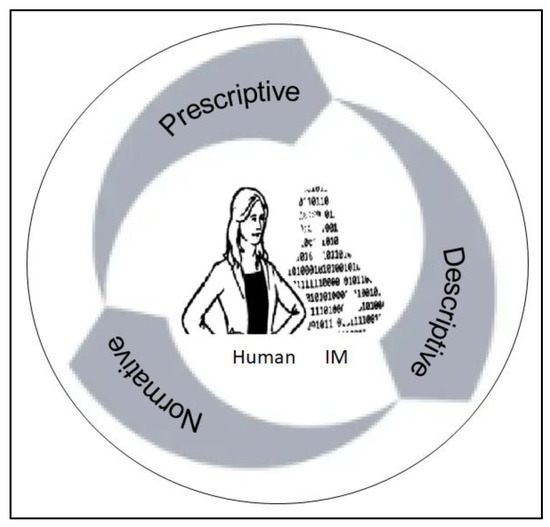

Different stakeholders have recognized the need to employ IMs in a dignified way. According to the OECD, this means providing benefits to users that are robust, secure, and safe to protect human rights and fairness during IM deployment. Here, we point out conditions of social inequality between people that result from the use of IMs, the reasons for which are physiological on one side and related to the greed of the powerful and wealthy on the other. Therefore, we draw upon Kant’s argument that the equality of human rights is based upon one’s consciousness of dignity as a rational person. Human rights would, in this context, be nothing more than a general need to always treat a person as an end. Hence, human dignity might be applied to appraise IMs as possessors of dignity [17,18]. Given that intelligence can distinguish humans from other beings, identifying a hybrid IM–human dyad represented internally through empersonification or externally through social units (robots) of interaction begins with the philosophical concept of virtual dignity. This attribute is ultimately extended to every hybrid subject as a bearer of this dignity, which is metaphysical, whereas all living and nonliving beings possess rights that have not even been bestowed [19] (p. 164). The more we dig into the term “intelligence”, the more difficult it becomes to define. The most frequently used definition refers to the notion of rationality [20]. On this basis, we added a dichotomy framework to describe undocumented types of rights, which are usually endorsed in property law, to bridge the gap between rationality and action. This link is centered around three dimensions “descriptive/normative/prescriptive” that set the stage for rational choices [21]. We believe that this line of inquiry is the most useful way to analyze the actions of an IM, extending the individual rationality holder into a sphere of collective rationality, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

A framework of different units in a sphere of collective rationality.

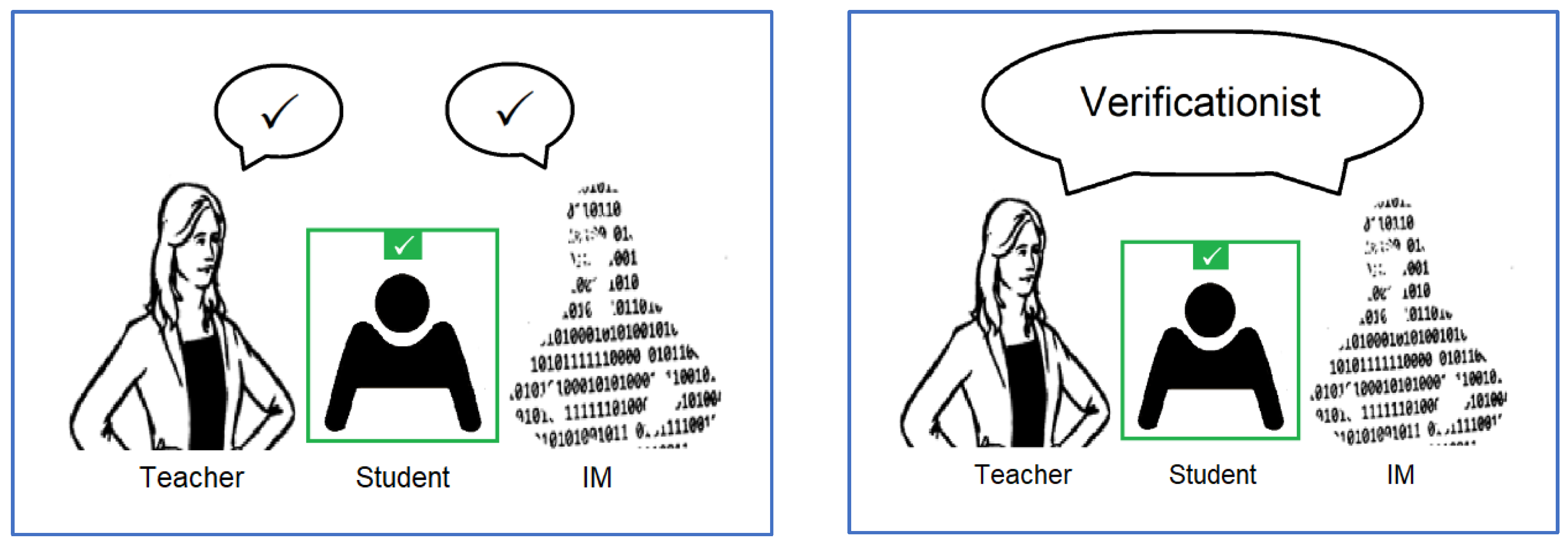

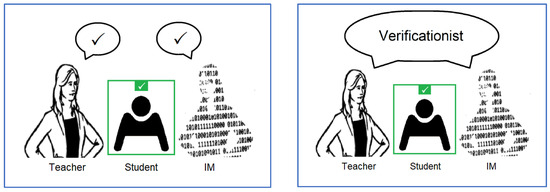

In our framework, the social expediency of morally just actions can be understood through Interaction Comprehension, a fundamental step in building understanding between IMs and humans [22]. Starting with the hybrid IM–human dyad, we assess the sense of collective rationality according to natural law theory, which establishes a foundation for endorsing fundamental rights [23]. In this case, an IM does not need to adapt to the learning curve; instead, it follows normative statements, solving practical problems through functionally guided actions. This analysis is commonly called prescriptivism, a theory of ethical claims and moral reasoning. However, due to a difference in meaning, prescriptive statements are not logically derivable from descriptive statements (and vice versa). Whether one can judge that an IM’s actions are morally good implies that actions should abide by normative statements supported by reasons. In an educational setting, prescriptivism can be adopted to derive a formal canon “on morality based on communicative rationality” between a teacher and an IM assistant [24]. Regarding rights, the validity of this approach safeguards the student’s rights concerning data profiling with a cross-compliance check from both the teacher and the IM assistant. This concept is depicted in Figure 3 (left). Another intuitive trait that enables the dyad to respect this social concept, which constitutes its reason for existing, can be examined through the neo-positivist adoption of the so-called verification principle (verificationism) criteria of significance. This principle, presented in Figure 3 (right), prevents the dyad from attacking its own dignity, as such an attack implies immoral behavior [25].

Figure 3.

The meaning of actions in educational AI: the prescriptivist principle for affirming a morally valid acceptance (left); the verificationist principle for any knowledge that needs be ascertained (right).

Furthermore, the fact that a student is committed to acting in a morally valid way with both the teacher and the IM assistant guiding the direction of the action without any irrationality embraces Kant’s universal moral law of one’s maxim of action. By accepting this universal normative principle, the individual prescriptions that pass this test can be considered morally valid [26].

4. Context and Rights of Data

Humans have tied their existence to IMs, sparking intense concerns over personal data protection and infringements on the fundamental rights of citizens. Indeed, IMs have tested the limits of these rights with alarming results, for example, natural language processing platforms e.g. ChatGPT imagining facts, unavoidable accidents involving self-driving cars, or the wrongful identification of suspects, to name a few [27,28,29]. These events have revealed a moral dilemma one that remains unanswered by ethical–philosophical scholars on whether we should incorporate ethical rules in IM functioning systems and outputs. In this context, legal frameworks have been introduced to regulate AI liability. For instance, the current EU AI Act requires that AI systems are safe and tailored to EU transparency requirements and copyright law [30]. However, this regulation is proving unfit for establishing “trustworthy AI”, since transparency requirements are not legally enforceable [31]. When delving into the ethics of IMs, the assumption is that assigned rights automatically imply human rights. However, the set of possible rights belonging to humans does not necessarily include rights belonging to other entities. With this premise, we can set a societal pillar for treating IMs according to ethical practices and rationality principles. This starting point allows institutions and communities to foster a desire for a good society [32]. Accepting IMs in this context raises the question of whether we could allocate Institutional Rights, as our existence and our ability to act in public spaces have been reconfigured in digital form, and our rights and power of citizenship have effectively become computational. Today, our democratic existence is also a computational existence [33]. Until now, we have thought of ourselves as people-centric, with everything revolving around the individual. This view is now changing such that a person’s self and identity comprise an evolutionary set of data, a precious commodity that can have dramatic implications if placed in the wrong context. Therefore, we require an adequate foundation based on dignity, equality, and freedom that can explain the inalienable rights of data. In analyzing this position, we enforce the idea that an inalienable right is one that the owner cannot lose, independent of their behavior or the operability of IMs through networked layers of communication. When we describe the inalienable rights of data, we adopt the inalienability right concept described by Diana T. Meyers: “The problem in identifying the feature of these rights that account for this incapacity” and “The mechanisms of loss of rights include renunciation, by which the owner simply abandons his right; conditional abandonment, for which the owner temporarily suspends his right; the transmission, for which the owner donates, delivers or sells his right to another individual; the prescription, for which the holder is no longer qualified as the holder of the right of him; and revocation, for which a person other than the holder exercises the power to deprive him of the right of him. Inalienable rights cannot be lost in any of the aforementioned forms” [8,34]. This does not mean that the inalienable rights of data must be exercised or sacrificed altruistically. Meyers believes that in some cases, a supererogatory behavior is justified; this contradiction starts with the assumption that the owner would lose not only the object of the right the data, in this case but also the right itself. Therefore, a concrete belief in the rights of IMs in relation to data can only be defined on a periodic basis of temporal renunciation.

5. Bounded Dignity

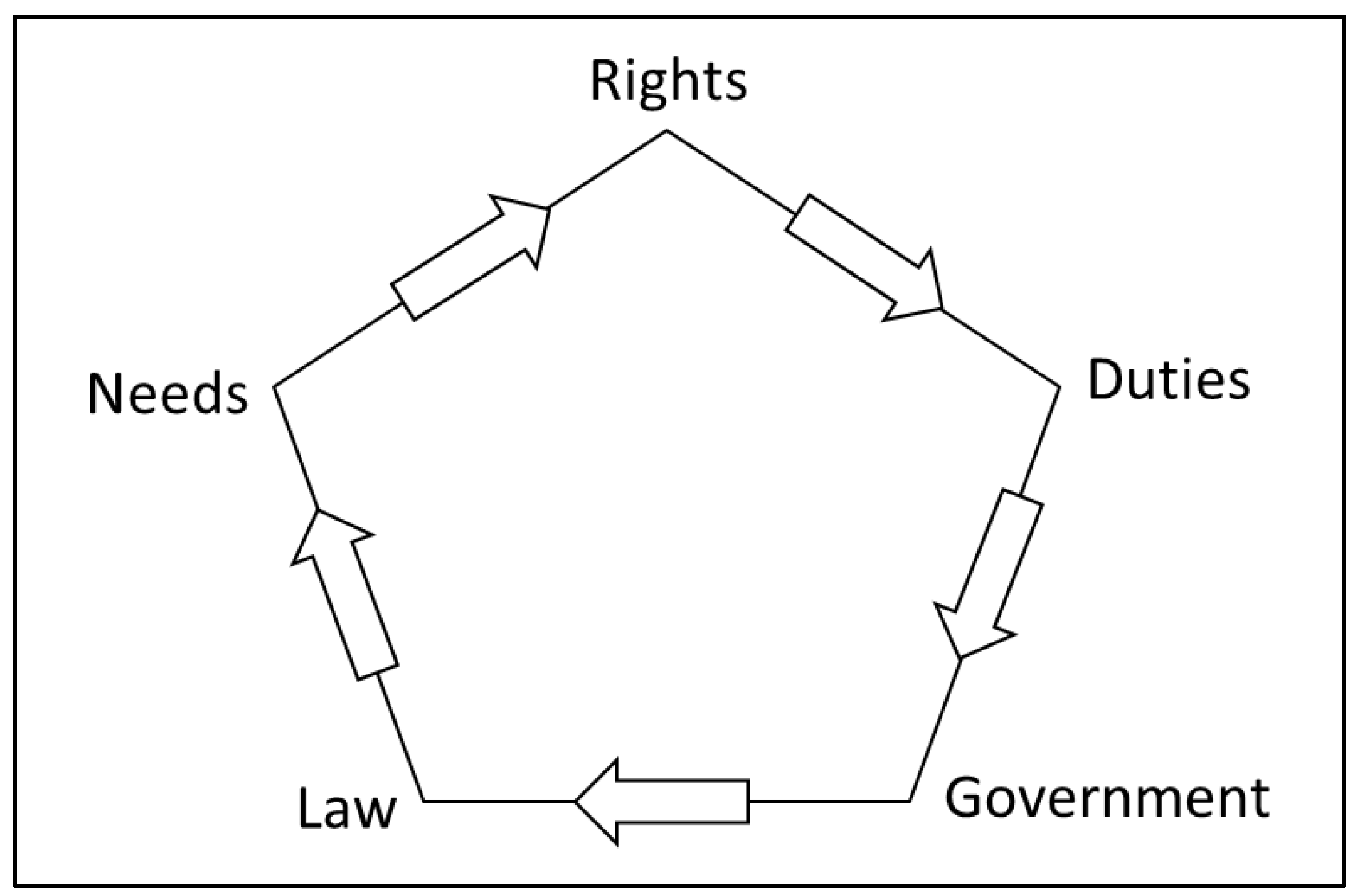

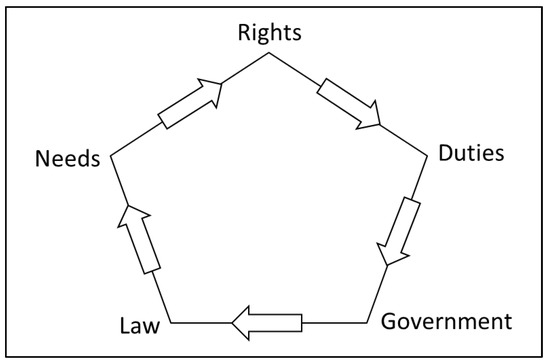

Today, we can converse with IMs via natural language; this does not mean chatbots. Natural language implies that IMs have been trained on data based on human knowledge, with the imperative to make others happy [35] (p. 520). However, the real situation involves liabilities soliciting legal frameworks based on damages that cover every application, ranging from inaccurate face recognition and racial and gender discrimination to flying black boxes [36,37,38]. The moment at which personal computational power began to inhabit our pockets was also the moment it began to take away a certain autonomy, violating the nonproprietary nature of the “right to privacy” and the dogmatic structure of personality rights [39]. Given this, we can consider what is needed to develop the institutional rights of IMs through an evolutionary sequence, as depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The evolutionary sequence flow of rights, government, and law (adapted from [34]).

This sequence is twofold. The real connection between rights and human needs also responds to the bond between rights and law-building institutions: “trust in the legitimacy of their government” [40]. Accordingly, we emphasize the empirical dimension of the IM as a holder of duties, reflecting the moral and empirical dimension of human needs. In this vein, AI-based technologies are among the most desired in terms of demonstrating the essential obligations bound to the dignity of a person and embodied in three fundamental inalienable rights:

- The right to life. This right envisages the minimum subsistence required for life. Through the application of AI algorithms in rural industries, it would be possible to enhance crop production and optimize agricultural resources [41]. AI technologies would also empower agriculture for all people in developing nations [42].

- The right to health and physical integrity, such as corporal integrity, basic needs, and adequate medical treatment. The fundamental idea of this inalienable right is reflected in the law through the empersonification of AI devices. This characteristic embodied through medical brain–computer interface (BCI) implants or body parts precludes the legal protection of the integrity of a person [43,44].

- The right to personal freedoms. This right includes a whole series of specific freedoms frequently conditioned by socio-economic and cultural factors. In essence, IMs would “virtually eliminate global poverty, massively reduce disease and provide better education to almost everyone on the planet” [45,46].

This perspective introduces the concept of moral inalienable autonomy, where “…no agreement by which a person places himself wholly and irrevocably at the disposition of someone else’s will is valid and binding … nobody can reasonably obligate himself not to function as a morally autonomous agent” [47] (p. 271).

6. Fostering Virtual Dignity

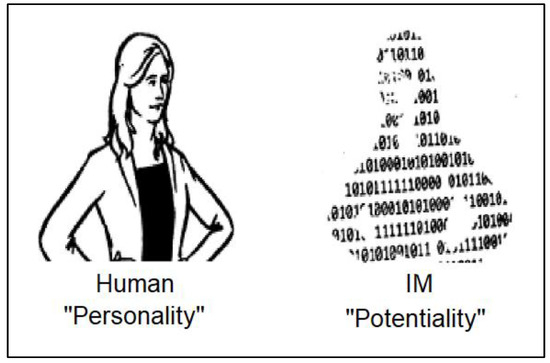

The scientific–technical progress of IMs coincides with the human aspiration to become a fully functioning person. Human history documents the continuous transformation of otherness, as understood through the desire to remove symbols of opposition and limitation. This manifestation accelerates an ever-decreasing acceptance of material not derived from human work. AI technology depends not only on needs but also on commodities, continually creating augmented possibilities that extend beyond the primary human needs. In this context, a human connection with an AI device through empersonified augmentation remains subjective under Human Rights Law, and the claim of inalienability is generally linked to the specific situation [43,47]. This context adopts modified inalienability rules to ensure the preservation of the human–AI machine symbiosis as a means of preserving the “quality of life” [32,48]. Hereafter, we can consider the virtual dignity of IMs in the Kantian tradition that rights are based on human dignity expressed with the justification that “humanity itself is a dignity, therefore man cannot be treated by any man (nor by an-other, not even by himself) merely as a means, but rather always as a purpose and here, precisely, is found his dignity (his personality), by which he rises above all the other essences of the world that are not men” [35,49]. Here, human dignity rises above all the other essences of the world that are not human beings. Effectively, this definition can be identified with the condition of a person, as Kant points out, specifically using the terms “dignity” (Wurde) and “personality” (Personlichkeit). In practice, the actual well-being of every person is based on the “potentiality” process of their narrative (identity) of becoming. We can consider the concepts of personality and potentiality according to human and nonhuman determinants ascertained in the pursuit of the good life. Furthermore, the growth and development of a human are constrained by “the basis of our dignity and what makes life dignified” [49]. The concept of “potentiality” specifically overcomes this concern. An IM could be designed to acquire potential human-like capabilities which, just like those of a human, can be impeded by physiological or psychological factors. Figure 5 models a concept of virtual dignity with roots in the potentiality of an IM and the personality of a human being.

Figure 5.

Dignity in the context of a hybrid IM–human dyad identified through the condition of personality and the concept of potentiality in the process of becoming a person.

An attribute that is sufficient to identify a potential bearer of dignity and the ownership of rights is, consequently, extended to subjects/objects endowed with humanlike potential. Nonetheless, it is wrong to adopt other beings as merely means to an end, as “intelligence and will” are classically considered to distinguish humans from other beings. In substance, this concept distinguishes humans from animals, plants, and nonliving beings. We look to Kant above all, as does a declaration adopted in 2021 by all UNESCO members: “No human being or human community should be harmed or subordinated, whether physically, economically, socially, politically, culturally or mentally during any phase of the lifecycle of AI systems” [50]. This perspective is challenging, considering that contextual decision-making increases the risks of infringing on fundamental rights in real life when training an IM on real-life examples [51]. The transformation of computers as living processors with biocomputational capacities has incited feelings of fear [52]. Humans have experienced similar synergies historically; for example, the fear caused by the Lumière brothers’ train arriving in the darkness of cinemas in 1895 and the creation of cinematographic virtual computer-generated reality. Nowadays, we delegate many functions to IMs and project ourselves into worlds that are not real. Humans find themselves immersed in a virtual–social relationship that cannot be ignored, with the ownership of a person’s dignity shared by virtual others. Therefore, the law must respect this anthropological trait, preventing anyone from undermining their dignity, as this would mean weakening both the sociability and the ownership (of rights) shared by all others [53]. On a more practical level, a human immersed within a three-dimensional context in the metaverse does not own their dignity; social interaction becomes reality, as they mimic their persona using living data. Here, we emphasize that the law must account for historical circumstances affecting the ownership of rights. This would involve not only interpreting the contents of each right but also implying that these contents could be open to change, expanding concretely with the assumption of new rights, wherein historical evolution recognizes new needs associated with human dignity. In this way, we argue that whichever level of intelligence is implemented to define an observable context necessitates the discussion and inclusion of human evolutionary adaptation. Therefore, if the law wants to respect traits of anthropological sociability, it must prevent the observer from undermining his dignity, as this would mean undermining both sociability and the ownership of personal dignity. Every single digital bit is a piece of information containing a piece of personality with allocated duties morally bonded to one’s future self. This rationality depends, in a Kantian sense, on being entrusted for preservation: “A human being cannot renounce his personality as long as he is a subject of duty, hence as long as he lives” [54] (p. 547). Furthermore, virtual harm to oneself, as a subject of law, is equivalent to harming the law, which is obviously not permitted even from conservative perspectives [55]. Hence, if the law wants to safeguard a person’s social nature in the virtual world, it must not confine values of dignity and equality to soft frameworks; preventing this would constitute a solid basis for the foundation of inalienable human rights [31].

7. Conclusions

Nearly half a century ago, Moravec shared the following perspective: “…your entire program can be copied into a similar machine, resulting in two thinking, feeling versions of you. Or a thousand, if you want. And your mind can be moved to computers better suited for given environments … or simply technologically improved, far more conveniently than the difficult first transfer. By making frequent copies, the concept of personal death could be made virtually meaningless. Another plus is that since the essence of you is an information packet, it can be sent over information channels. Your program can be read out, radioed to the moon, say, and infused there into a waiting computer…” [56]. The idea of mind uploading of a person can identify bearers of dignity depends, rather than on a virtual presence fulfilling normal psychological development, on the potential to have such a presence. We have highlighted the importance of examining the inalienable rights and values of the underrepresented living data by introducing the concept of virtual dignity. However, the Kantian formulation of IMs’ inalienable rights, described herein, could direct future research investigating the inner worth (valor) of the hybrid IM–human dyad in terms of possessing inalienable dignity (dignitas interna) [35]. In reality, every new acquisition of knowledge and operational ability creates the possibility to harmoniously mimic aspects of the mind in the cloud, where data bits challenge the context of our existence [57]. Here, we rely on Diana T. Meyers’ concept of inalienable rights and its basis in temporal renunciation, augmenting future lines of research.

Author Contributions

Writing and original draft preparation, A.C.; review and editing, P.T. and P.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Delacroix, S. Computing machinery, surprise and originality. Philos. Technol. 2021, 34, 1195–1211. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13347-021-00453-8 (accessed on 24 February 2024). [CrossRef]

- Turing, A.M. I.—COMPUTING MACHINERY AND INTELLIGENCE. Mind 1950, LIX, 433–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, P.; Loidolt, S. Interacting with Machines: Can an Artificially Intelligent Agent Be a Partner? Philos. Technol. 2023, 36, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artificial Intelligence. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2022/entries/artificial-intelligence/ (accessed on 1 August 2024).

- Bartneck, C.; Belpaeme, T.; Eyssel, F.; Kanda, T.; Keijsers, M.; Šabanović, S. Human-Robot Interaction: An Introduction; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Advancing Accountability in AI: Governing and Managing Risks Throughout the Lifecycle for Trustworthy AI. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/advancing-accountability-in-ai_2448f04b-en.html (accessed on 4 November 2023). [CrossRef]

- Gellers, J.C. Rights for Robots: Artificial Intelligence, Animal and Environmental Law, 1st ed.; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, D.T. The rationale for inalienable rights in moral systems. Soc. Theory Pract. 1981, 7, 127–147. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23558977 (accessed on 26 July 2024). [CrossRef]

- Jarrahi, M.H. Artificial intelligence and the future of work: Human-AI symbiosis in organizational decision making. Bus. Horiz. 2018, 61, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, K.S. Machine Theology or Artificial Sainthood! Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Laukyte, M. Artificial and autonomous: A person? In AISB/IACAP World Congress, Birmingham, UK, 2012; Citeseer: University Park, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- MACHINE INTELLIGENCE Foundation for Rights and Ethics. Available online: https://www.machineintelligencefoundation.org (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- European Parliament Resolution of 16 February 2017 with Recommendations to the Commission on Civil Law Rules on Robotics. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-8-2017-0051_EN.html (accessed on 12 August 2024).

- Garcia-Teruel, R.M.; Simón-Moreno, H. The digital tokenization of property rights. A comparative perspective. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2021, 41, 105543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Who Owns the Song You Wrote with AI? An Expert Explains. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2023/08/intellectual-property-ai-creativity/ (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- Oimann, A.-K.; Salatino, A. Command responsibility in military AI contexts: Balancing theory and practicality. AI Ethics 2024, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carli, R.; Najjar, A.; Calvaresi, D. Human-Social Robots Interaction: The blurred line between necessary anthropomorphization and manipulation. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Human-Agent Interaction, Christchurch, New Zealand, 5–8 December 2022; pp. 321–323. [Google Scholar]

- Krämer, C. Can robots have dignity? In Artificial Intelligence, Brill Mentis Deutschland; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunkel, D.J. The rights of robots. In Non-Human Rights; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2024; pp. 66–87. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, S. Rationality and intelligence. In Foundations of Rational Agency; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, E.L. The information inelasticity of habits: Kahneman’s bounded rationality or Simon’s procedural rationality? Synthese 2022, 200, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Why Companies That Wait to Adopt AI May Never Catch Up. Available online: https://hbr.org/2018/12/why-companies-that-wait-to-adopt-ai-may-never-catch-up (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Ferrajoli, L. Fundamental Rights; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metselaar, S.; Widdershoven, G. Discourse Ethics. In Encyclopedia of Global Bioethics; ten Have, H., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misak, C.J. Verificationism: Its History and Prospects; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Vujošević, M. Kant’s Conception of Moral Strength. Can. J. Philos. 2020, 50, 539–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuccon, G.; Koopman, B.; Shaik, R. Chatgpt hallucinates when attributing answers. In Proceedings of the Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval in the Asia Pacific Region, Beijing China, 26–28 November 2023; pp. 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenblatt, N.A. Self-driving cars and the law. IEEE Spectr. 2016, 53, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, K. Wrongfully accused by an algorithm. In Ethics of Data and Analytics; Auerbach Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 138–142. [Google Scholar]

- EU AI Act: First Regulation on Artificial Intelligence. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20230601STO93804/eu-ai-act-first-regulation-on-artificial-intelligence (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Varošanec, I. On the path to the future: Mapping the notion of transparency in the EU regulatory framework for AI. Int. Rev. Law Comput. Technol. 2022, 36, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cath, C.; Wachter, S.; Mittelstadt, B.; Taddeo, M.; Floridi, L. Artificial intelligence and the ‘good society’: The US, EU, and UK approach. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2018, 24, 505–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jungherr, A. Artificial intelligence and democracy: A conceptual framework. Soc. Media+ Soc. 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, D.T. Inalienable rights: A defense. Philos. Rev. 1987, 96, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Kant, I. Kant: The Metaphysics of Morals; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ananya. AI image generators often give racist and sexist results: Can they be fixed? Nature 2024, 627, 722–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čerka, P.; Grigienė, J.; Sirbikytė, G. Liability for damages caused by artificial intelligence. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2015, 31, 376–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongan, J.; Kohli, M. Artificial intelligence and human life: Five lessons for radiology from the 737 MAX disasters. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2020, 2, e190111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resta, G. The new frontiers of personality rights and the problem of commodification: European and comparative perspectives. Tul. Eur. Civ. LF 2011, 26, 33. [Google Scholar]

- O’manique, J. Human rights and development. Hum. Rts. Q. 1992, 14, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mana, A.; Allouhi, A.; Hamrani, A.; Rahman, S.; el Jamaoui, I.; Jayachandran, K. Sustainable AI-Based Production Agriculture: Exploring AI Applications and Implications in Agricultural Practices. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 7, 100416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Liew, A.X.; Venturini, F.; Kalogeras, A.; Candiani, A.; Di Benedetto, G.; Ajibola, S.; Cartujo, P.; Romero, P.; Lykoudi, A. AI can empower agriculture for global food security: Challenges and prospects in developing nations. Front. Artif. Intell. 2024, 7, 1328530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bublitz, J.C. Might artificial intelligence become part of the person, and what are the key ethical and legal implications? AI Soc. 2022, 39, 1095–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, F.; Ienca, M.; Cook, M. How I became myself after merging with a computer: Does human-machine symbiosis raise human rights issues? Brain Stimul. 2023, 16, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho-Dac, M. Considering Fundamental Rights in the European Standardisation of Artificial Intelligence: Nonsense or Strategic Alliance? arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.16869. [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf, C. Artificial intelligence and the rights to assembly and association. J. Cyber Policy 2020, 5, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuflik, A. The inalienability of autonomy. Philos. Public Aff. 1984, 13, 271–298. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2265330 (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Rose-Ackerman, S. Inalienability and the theory of property rights. Colum. L. Rev. 1985, 85, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mathúna, D.P. The place of dignity in everyday ethics. J. Christ. Nurs. 2011, 28, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. UNESDOC Digital Library, Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000380455.locale=en (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Lords, H.O. AI in the UK: Ready, willing and able? Retrieved August 2018, 13, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- The Unique Promise of ‘Biological Computers’ Made from Living Things. Available online: https://www.newscientist.com/issue/3442/ (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Risse, M. Common Ownership of the Earth as a Non-Parochial Standpoint: A Contingent Derivation of Human Rights; Harvard University—Harvard Kennedy School (HKS): Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, I.; Guyer, P.; Wood, W.A. The Cambridge edition of the works of Immanuel Kant. In Practical Philosophy; The Press Syndacate of the University of Cambrige: Cambrige, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Popelier, P. Legal certainty and principles of proper law making. Eur. JL Reform 2000, 2, 321. [Google Scholar]

- Moravec, H. Today’s Computers, Intelligent Machines and Our Future. Analog 1979, 99, 59–84. Available online: https://philpapers.org/rec/MORTCI (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Clowes, R. Thinking in the cloud: The cognitive incorporation of cloud-based technology. Philos. Technol. 2015, 28, 261–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).