Retrogradation of Truth and Omniscience

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Todd and Rabern’s Argument

- Omni-accuracy

- (i)

- Reject the principle of the fixity of the past. However, this is a very costly option. To be sure, it is entirely acceptable that the correctness of a belief or a statement might change over time. Suppose, for instance, that someone says on December 9th: “It will rain tomorrow”. If it is indeterminate whether it will rain the next day, it is also indeterminate whether this statement is correct. However, on December 10th, being a rainy day, one might say: “It is raining. You were right: your statement yesterday was correct”. Nevertheless, it seems unacceptable that on December 9th it is not true that God believes p, yet the next day it becomes true that on December 9th God believed p. The correctness of a belief is a relational fact between that belief and what makes it true. What makes it true may be a future fact that is not determined today. The fact that God believes something, however, is not a relational fact; it is entirely contained within a single moment in time. It thus seems that implies an intrinsic alteration of the past.4

- (ii)

- Reject Omni-accuracy. However, this implies that the existence of an omniscient being is not possible. As Todd and Rabern observe, “In general, one could argue that a semantic theory—a theory concerned with the logic and compositional structure of the language—ought not to settle certain substantive non-semantic questions” (p. 116).

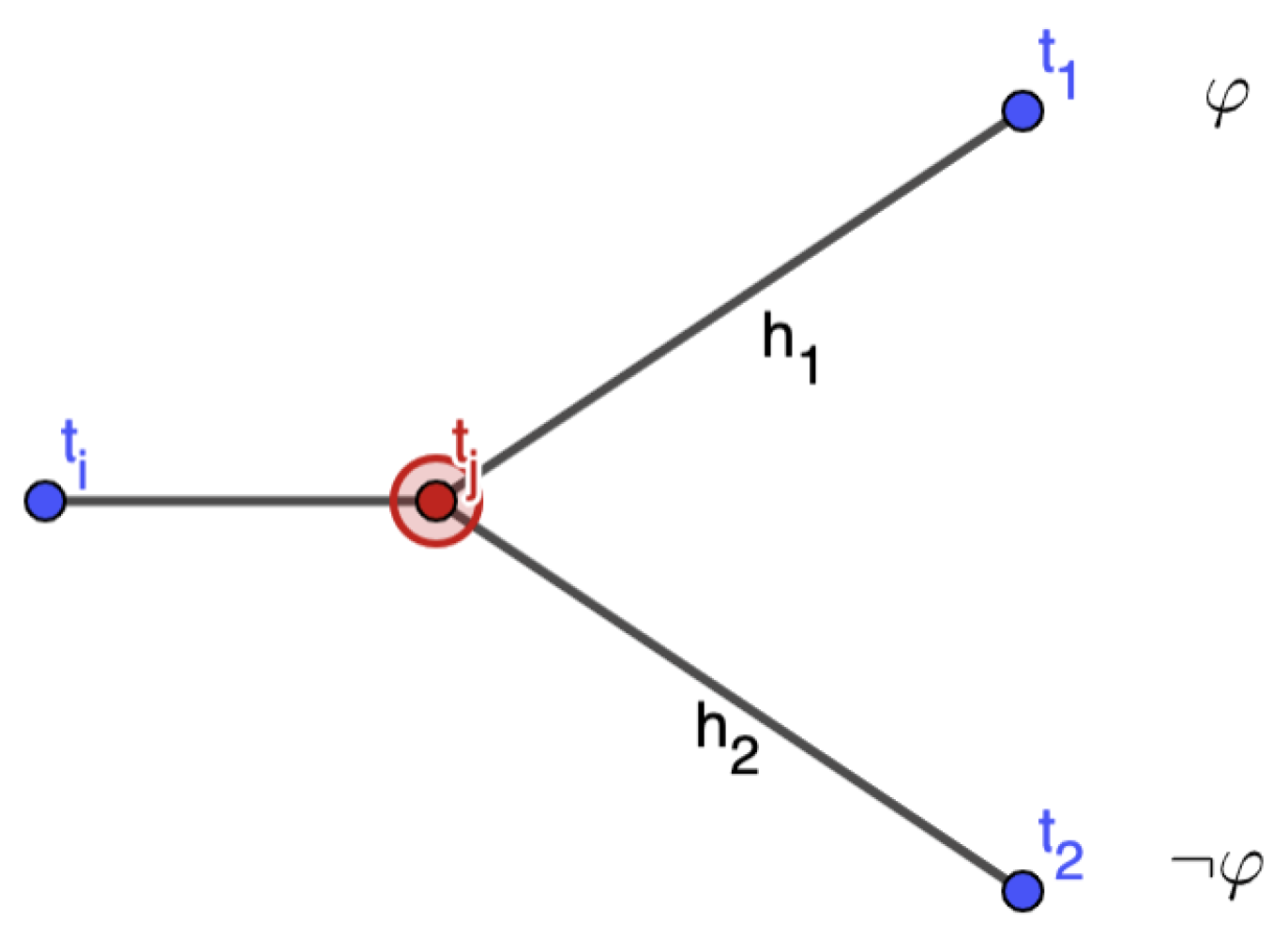

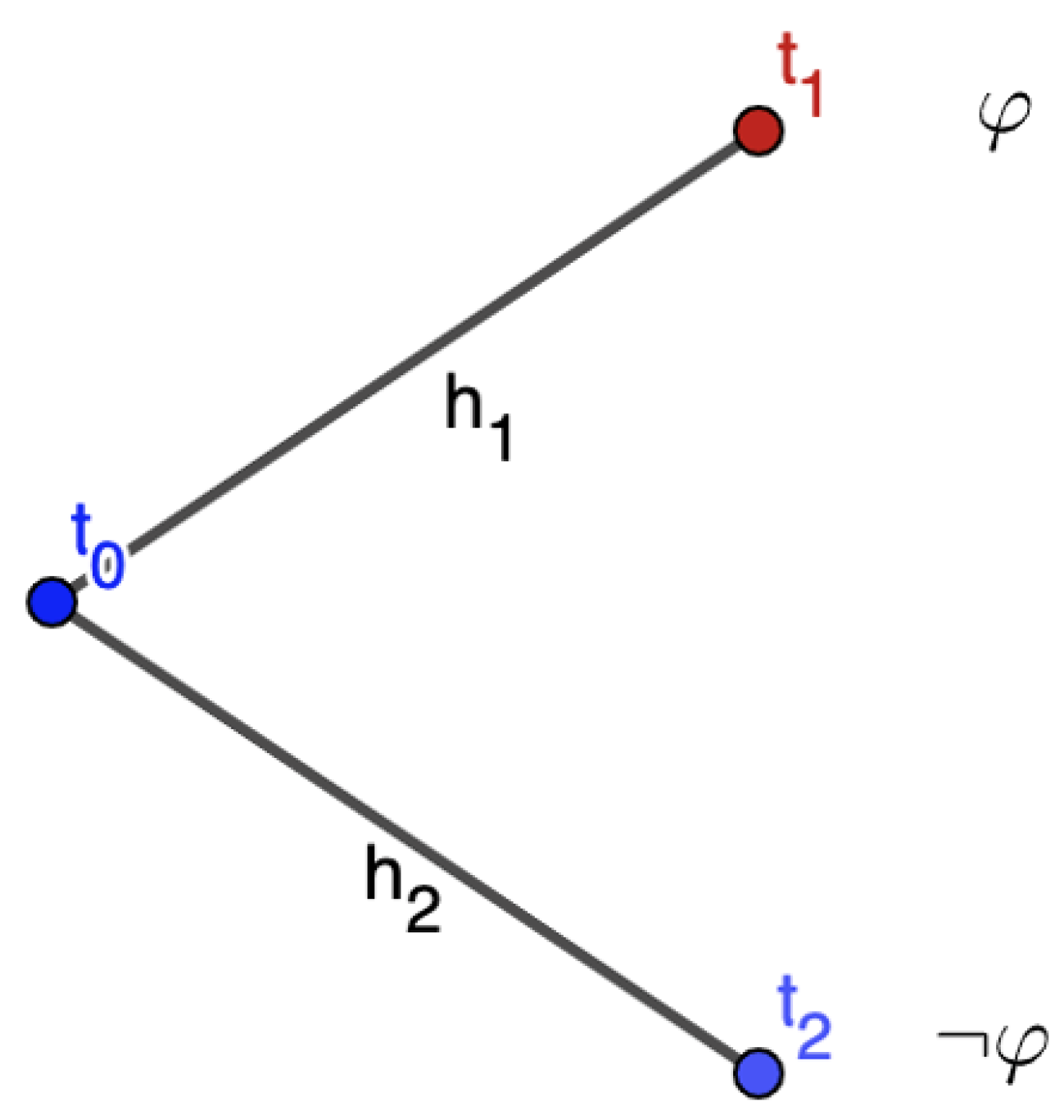

3. Branching Time and Evaluation of Future Tense Sentences

- ()

- ()

4. Retro-Believing and Retro-Truth

4.1. Double-Indices Semantics

4.2. The Possibility of Omniscience

- ()

- (Omn-)

- For every t,

5. A Timeless God

- Emma’s freedom: God knows that at time t and from the perspective of t, it is neither true nor false that Emma will attend the party. The future before her is thus indeterminate, and she is free to determine it as she wills.

- Divine omniscience: From the divine privileged standpoint, for every t and , the following holds:God knows the truth of every proposition and does not believe any proposition that is not true.

- The principle of retrogradation: While is not true, is. By changing the perspective—that is, the “present”—the truth value of future propositions also changes.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | For the invalidity of in classical semantics, see [7]. |

| 2 | and represent metric temporal operators. Their interpretation is straightforward: considering one day as the temporal unit, means that it was true yesterday that p; analogously, means that it will be true tomorrow that p. |

| 3 | As an anonymous referee observes, the transition from to this formula, even assuming Omni-accuracy, is not straightforward. We must assume that and are interchangeable even when appears within a temporal operator. Todd and Rabern justify this transition by asserting that God remembers everything that is past and predicts everything that is future. Therefore, is always substitutable with and with , where and are operators referring to God’s psychological states. Consequently, from , we can derive . However, predicting something entails believing that it will happen. Thus, from , we can infer . We agree with the reviewer that this inference could be challenged in various ways, but for the purposes of this paper, we will assume it without further comment. |

| 4 | MacFarlane in [13] contends that Todd and Rabern’s argument relies on a substantive metaphysical premise: past and present beliefs are settled. This premise can be challenged according to MacFarlane. Nevertheless, it is unclear why past and present beliefs should not be fixed like any other past or present facts. MacFarlane cites [14] to defend the notion that past and present beliefs are not settled. However, Jackman argues that a past belief remains unsettled when it involves meanings that are indeterminate and are subsequently clarified over time. Ultimately, future usage determines past usage of a term. According to Jackman, such cases may be relatively rare. However, this question is orthogonal to the argument proposed by Todd and Rabern because divine past beliefs regarding future contingents remain problematic according to the argument even when dealing with completely determinate meanings. |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | A version of perspectival semantics in which the evaluation instant and the now are not connected has been proposed for counterfactual semantics in [19]. |

| 8 | In the following, we will also apply the () principle to cases of disbelief. This is reasonable, as disbeliefs are representational attitudes toward the world. The underlying idea is that if a proposition is untrue (due to its indeterminate truth value or to its falsity), then an omniscient entity does not believe it to be true. |

| 9 | Todd and Rabern do not specify the semantic system underlying their argumentation. Therefore, we assume that their satisfaction relation (⊧) involves a quantification over temporal instants. |

| 10 | One might propose a theory according to which only God’s beliefs are temporal, while God Himself is a timeless entity. Such a theory would, of course, need to account for how a timeless being can hold beliefs within time. However, what matters in the present context is divine omniscience—that is, whether God’s beliefs are temporal or not. We may therefore set aside the question of God’s own temporality. For the sake of simplicity, we shall refer to God as either temporal or non-temporal, without addressing the possible distinction between the temporality of His beliefs and the temporality of the divine being itself. |

| 11 | For a similar view, see [21]. |

| 12 | An anonymous referee objects that this is not true because if is true at the index , it is false that at the same index that . So, if we pick the index (i.e., evaluation and perspective ), holds and does not. This is a consequence of . We grant this point. However, if is true at the index , the omniscient entity believes that is true at the index . In other words, if it was true yesterday that it would rain today, then God believes today that yesterday it was true that it would rain today. Therefore, God believes today that was true yesterday. This, in effect, means that God believes that is true at the index . Nevertheless, we acknowledge that our system does not fully account for this, as it avoids delving into the details of the semantics of . While such an analysis could be provided, we have chosen to avoid it in this context in order to keep our response to Todd and Rabern’s argument as concise as possible. However, we concede that a complete response to their argument should include a detailed examination of the divine belief operator. |

References

- Todd, P.; Rabern, B. Future contingents and the logic of temporal omniscience. Noûs 2021, 55, 102–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomason, R. Indeterminist time and truth-value gaps. Theoria 1970, 36, 264–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacFarlane, J. Future contingents and relative truth. Philos. Q. 2003, 53, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacFarlane, J. Assessment Sensitivity: Relative Truth and Its Applications; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, P. The Open Future. Why Future Contingents Are All False; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, P. Future contingents are all false! On behalf of a Russellian open future. Mind 2016, 125, 775–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belnap, N.D.; Green, M. Indeterminism and the thin red line. Philos. Perspect. 1994, 8, 365–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKim, V.R.; Davis, C.C. Temporal modalities and the future. Notre Dame J. Form. Log. 1976, 17, 233–238. [Google Scholar]

- Øhrstrøm, P. In defence of the thin red line: A case for Ockhamism. Humana Mente 2009, 8, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Iacona, A. Ockhamism without thin red lines. Synthese 2014, 191, 2633–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawer, J. The truth about the future. Erkenntnis 2014, 79, 365–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawer, J.; Malpass, A. Back to the actual future. Synthese 2020, 197, 2193–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacFarlane, J. Why future contingents are not all false. Anal. Philos. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackman, H. We live forwards but understand backwards: Linguistic practices and future behavior. Pac. Philos. Q. 1999, 80, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belnap, N.D.; Perloff, M.; Xu, M. Facing the Future: Agents and Choices in Our Indeterminist World; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Øhrstrøm, P.; Hasle, P. Temporal Logic: From Ancient Ideas to Artificial Intelligence; Kluwer Academic Publisher: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- De Florio, C.; Frigerio, A. Retro-Closure Principle and Omniscience. Dialectica 2023, 77, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- De Florio, C.; Frigerio, A. Divine Omniscience and Human Free Will. A Logical and Metaphysical Analysis; Palgrave MacMillan: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- De Florio, C.; Frigerio, A. The Thin Red Line, Molinism, and the flow of time. J. Log. Lang. Inf. 2020, 29, 307–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamp, E.; Kretzmann, N. Eternity. J. Phil. 1981, 78, 429–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leftow, B. Time and Eternity; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA; London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Florio, C.; Frigerio, A. Retrogradation of Truth and Omniscience. Philosophies 2025, 10, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies10020046

De Florio C, Frigerio A. Retrogradation of Truth and Omniscience. Philosophies. 2025; 10(2):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies10020046

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Florio, Ciro, and Aldo Frigerio. 2025. "Retrogradation of Truth and Omniscience" Philosophies 10, no. 2: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies10020046

APA StyleDe Florio, C., & Frigerio, A. (2025). Retrogradation of Truth and Omniscience. Philosophies, 10(2), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies10020046