1. Introduction

Santiago Diez-Fischer

1 once told me that his music had to go beyond the sound experience. The composer wanted to create an action, a multisensory event that, starting from sound and gesture, could express its unique temporality by evoking bodily and tactile experience, at the limit of the invisible and the microscopic. Diez-Fischer’s music mobilizes the deepest experience, the one that develops through the practice of acousmatic listening [

1]

2—that is, without a visual reference to the corporeity of the instrument and the musician—performed by performers in the flesh in front of the listener. Santiago Diez-Fischer’s music is made for concerts, for the stage, to be enjoyed in a concentrated manner, and performed with great care. However, the sound produced is so peculiar that it is not immediately possible to understand its instrumental origin; it is a continuous, rough, noisy sound, like the sound one can hear when closed up in an enclosure, blind, in a metropolitan landscape. What may immediately seem threatening is actually extremely delicate; listening to these sound textures feels like caressing an unfamiliar fabric or skin. It is a destabilizing sensation, but one that can make you experience profound feelings.

This acousmatic instrumental music creates a paradoxical situation and defines a unique experience, bordering on the sonorous and the tactile. Such a compositional choice stems from an explicit desire on the part of the composer. It is a way of involving the listener more: making them listen to an extremely physical, non-musical sound, which does not require knowledge of the conventions of concert and instrumental performance, enables them to understand the music by recalling deeper experiences. This sound is more immediate and therefore produces a more intense and communicative sensation, so intense, at times, that the listener may be shocked. Through his particular musical choices, Diez-Fischer wants to resonate the energy that develops through contact with the sound body, that relating to movement. One must then forget the music and let oneself be drawn into the primordial sound experience. The rubbing and caressing of the sound surfaces, the sudden blows and the noise then become breaths, respirations, extremely corporeal and close sounds, so familiar that they constitute the background of consciousness, which re-emerges when we put ourselves in a condition of deep listening. The composition of such music goes hand in hand with the development of a notation that indicates the movement to be made by the musician, the surface or the sound body to be set into vibration.

In this text, I argue that the pieces written by Santiago Diez-Fischer are presentation symbols of the sense of touch; these symbols are expressed by specific work on instrumental timbre and consequently must be based on a very particular notation. To demonstrate this, I will show how the presentational symbol of touch expressed by Santiago Diez-Fischer’s music is expressed through instrumental techniques and written in his scores. In this way, I show how this presentational symbol, which results from what Susanne Langer called a “symbolic transformation of experience” [

2] leans particularly on the musical instrument as a body to be touched. Notation then defines the meeting point between sound and tactile experience thanks to the performer’s ability to imagine the timbral result of the movements they make. The notation invites you to discover the body of the instrument as if you were touching a living body. The meaning of such a symbol then emerges from the interaction between the instrumental performance and the sound produced, which evokes sensations that are not only musical, but deeply rooted in proprioceptive experience.

2. Presentational Symbolism as Method

Susanne Langer’s philosophy is closely linked to the concept of symbol; for Langer, the symbol is a vehicle of knowledge [

3]: symbols are not merely signs in place of the indicated object, but are a ways of knowing or even conceiving it. For this reason, creating or perceiving a symbol makes it possible to develop an in-depth awareness of the thing represented; indeed, through the symbol, one is able to think the thing and understand it. Langer distinguishes between discursive symbols and presentational symbols. The presentational symbol is similar to the discursive symbol, the only difference being that it does not use language to indicate aspects of the thing symbolized, but includes these elements and makes them perceptible: the presentational symbol has the form of the thing represented. This symbol does not serve to discuss something, but presents the thing itself and gives an interpretation through a form. For this reason, it is not a representation but a presentation. If the discursive symbol uses words and language, the presentational symbol uses undefined languages and grammars, which change substantially depending on the user.

Music is a special case of this type of symbolization; music is a presentational symbol of emotions [

2] says Langer; it expresses emotion by presenting its form. Articulation and expressivity are the main characteristics of music, rather than assertion and expression; music is therefore a formulation and presentation of emotions, feelings, tensions, and mental resolutions. Defined by forms that are isomorphic to inner experience, music narrates them in an articulate manner. Emotions are thus presented, as such, to our understanding [

2]; music, through processes of movement and growth or repeated motifs [

3], is a logical expression of feelings [

2]. The presentational symbol, unlike the discursive symbol, has an implicit meaning [import] [

2], which nevertheless provides access to a certain kind of knowledge. Such knowledge is that of inner experience in general, which the musician presents through his practice. Music allows the musician to present their inner experience through a sound object that somehow resonates with the listener. However, such a symbol is not capable of fully communicating this experience; it is an ‘unconsumated symbol’ [

2], which can only be fully understood by the one who creates it.

Here, in this text, I apply the notion of a presentational symbol and expand its application. Now, music can generally be thought of as a presentational symbol that expresses through movements and tensions the experience of the musician who conceives it. The meaning of such a symbol is not full, it is defective, unconsumated; it has features that can be understood but not completely; this is because it is a kind of artificial language. I think Langer’s idea is right, but fails to indicate precisely how such an implicit meaning can be partially understood. I think it can be understood through listening and, in this case, reading scores. Listening sets the listener’s imagination in motion and thus makes the music resonate in their internal experience. It is precisely this experience that is mobilized and from there the meaning can appear; although it will be different for each of us, it can probably present common traits among us all.

From a methodological point of view, I think that Langer’s theory can be extended through the idea of aspectual listening, developed, for example, by Alessandro Arbo [

4], or that of François Delalande’s listening behaviors [

5]; in particular, the latter shows how listeners all hear differently, but that perhaps certain types of listening are sufficiently common such as empathic or figurative or narrative listening. To define the meaning of Diez-Fischer’s music, I have basically applied empathic listening, which tries to link listening to bodily experience. Listening means, after all, ‘listening as’, in other words, interpreting. In some ways, Paul Ricœur also supported the same idea. For the French philosopher, meaning emerges metaphorically, as a ‘being as’ [

6]. After several listenings, I started to listen to Diez-Fischer’s music

as if it presents a tactile experience.

I think that each piece of music is a language in itself, different from the others, because it expresses certain interior experiences that have no visible or linguistically defined counterpart. In this sense, the experience expressed by the music is not semantically effective; however, the music has the power to move the inner experience of the listener and therefore to be understood in this sense. Consequently, if every music is a language in itself, every interpretation is an interpretation in itself. The next step would be to see if the interpretations have common features, as Delalande proposes to do, or as, basically, what Bachelard also proposed in his

Poétique de l’espace [

7]: the listener has to make the music resonate in his or her experience in order to understand it.

I did so. The music I present here is strongly characterized by gestures similar to caressing, rubbing, punching, and slapping, all actions that evoke tactile sensations in a profound way. I think then that Santiago Diez-Fischer’s music is a presentational symbol of the sense of touch; that is, the composer symbolically transforms his experience of touch through the music he composes. Thanks to the special instrumental techniques employed, the composer precisely moves the tactile experience of the performer and the listener.

3. Touch, Body, Gesture in Acousmatic Thinking

Diez-Fischer’s music is not electronic, but it sounds very close. Indeed, for me, it is an acousmatic instrumental music. Now, the fact that musical experience is not only auditory but involves all the senses is something that musicians, but also musicologists, have well understood. Considering this issue from the point of view of cognition [

8], of semiotics [

9] or listening behavior [

10], and hermeneutics [

11], few today would isolate the issues of listening from those of multimodal perception, culture, and society.

The idea that music is a presentational symbol of unseen experience is well understood by composers, particularly by electroacoustic composers. But why would this idea be important for understanding Diez-Fischer’s music? Indeed, most of Santiago Diez-Fischer’s works are instrumental or mixed (i.e., for instruments, voices, and electronic devices); however, the origin of his work has its roots in electroacoustic music, particularly in acousmatic music

3. It is precisely by drawing inspiration from this music that Diez-Fischer manages to evoke tactile sensations, bordering on the purely corporeal; he thus manages to escape the dominance of vision in music. In this sense, his work ties in with the thinking of acousmatic composers, for whom work on sound is not an end in itself, but mobilizes the whole of the experience in order to move and, for François Bayle, even disrupt it

4.

According to composer Annette Vande Gorne, acousmatic music is primarily based on bodily experiences, which are strongly linked to the sensations arising from the manipulation and contact of sound bodies. These are “energy models”, which are inspired by the experience of sound production and touch. Among these models, rubbing and granulation—a sound process that highlights the smallest elements that make up a sound, below twenty milliseconds—play an extremely important role [

12].

For composer Denis Smalley, sound energy mobilizes the listener’s experience in a broad sense, and in particular, the bodily experience. The musical gesture, understood as the point of contact between the movements that the music evokes and those that the listener’s memory picks up, starting from his own experience, conveys tactile, visual and aural experiences simultaneously [

13]. Smalley proposes two key concepts to grasp this aspect: gesture and texture. The first concerns movements temporally oriented toward a direction; the second concerns sounds that instead move within them and seem static globally. Gesture is directional, theatrical, implying a narration whose story tells of the projection of the character outwards, in interaction with other unexpected characters; texture, on the other hand, is encompassing, maternal, tactile, non-visible, in a suspended time; it provokes empathic listening, as François Delalande would say, which solicits the experience of proximity [

5].

In acousmatic music, these two forming principles—or archetypes, for Smalley—coexist and constitute a conceptual continuum that characterizes the reference to the musical agent and the sound source [

13]. This recognition implies a certain psychological tension and expectation: if a sound seems to be produced by a certain gesture and a certain material, it should have a certain time course. If, on the other hand, such a recognition is not respected by the sound one hears, then the tension and musical attention are amplified. Long, textural sounds, those that are characterized by an internal movement predominating over their external profile, evoke tactile sensations, which come from the details of musical gestures [

14]. Human gestures, for Smalley, are connected to the proprioception of bodily tensions. The tension and resistance of the bodies express the emotional and psychological experience in a broad sense [

15]. Spectromorphology, which is the name Smalley gives to his theory, involves the emergence of a sound imagination that involves all the senses and refers to the experience tout-court [

15]. Diez-Fischer’s music works on textures filled with gestures, what Smalley calls

texture-setting [

13]. In this music, the energy field produced by the instrumental gesture performed by the musician dramatically expresses an emotion, either through a violent movement or an “intimate caress” [

15], an “extreme strength and gentleness” [

15]. Here, acousmatic music is a presentational symbol of gestural, proprioceptive experience, in much the same way as Diez-Fischer.

Traces of this compositional attitude can also be found in the music of François Bayle, a very important acousmatic composer

5. Bayle thinks that sound—listened to as such, produced by loudspeakers in concert—is a vector of total experience, capable of speaking, like a sensitive sign, to the interiority of the listener, mobilizing all their experience. For Bayle, the sound image, what he defines as

i-son, presents, in a “general figurativeness, […] all audible contours […], from realism to the fiction of the ideal form” [

1]. Acousmatic music sets “auditory intuition” in motion, in order to “shift the formation of perceptual thinking” [

1]. Such a thought, set in motion by sound experience through the electroacoustic medium, results from the activity of the “hand-ear”; it is a manifestation of life, says Bayle [

1]. Bayle extracts forms from sensory experience in order to revive them through the listener’s imagination. Bayle’s work mobilizes sound archetypes, understood as “basic figures on which life’s learning is elaborated” [

16]. It is no coincidence that his theorization finds an echo, again, in that of the philosopher Paul Ricœur [

17], and refers in particular to the theory of mimesis that the French philosopher explored in his important work

Temps et récit [

6].

Trevor Wishart also explored the links between sound and context. Listening, through sound, would reveal this context, which is intimately part of the horizon of perception, from which it cannot be abstracted. Wishart makes particular reference to the sonic space that is conveyed by the sound [

18]. For instance, says the composer, in the case of orchestral music, the landscape that emerges is precisely that of the instrument as well as of the concert hall, the musical practices and the stories linked to that type of sound. Wishart works with the “landscapes” that the sound evokes, to the point of defining images and sound metaphors in order to structure the music. This work, carried out with extreme coherence since the 1970s (e.g., the pieces

Journey into space (1973),

Red Bird (1973–1978)) continues until the most recent ones (e.g.,

Encounters in the Republic of Heaven (2012–2020)). The work on the sound image, conceived as an instrument capable of evoking multimodal images and sensations, is at the center of his language. In his piece

Red Bird (1973), the very structure of the music is conceived on the basis of sound metaphors such as freedom, through the figure of the bird, and imprisonment and imagination, through the elaboration of transformative configurations.

Acousmatic music theories all emphasize a particular relationship between music and experience. Acousmatic music takes the experience tout-court, that of touch, of listening, of musical and sonorous memory in general, and creates works which, thanks to the experiences evoked, have the ambition of coming into direct contact with the listener’s imagination. In this sense, acousmatic music is paradigmatic from a Langerian point of view. This music is a true symbolic transformation of experience, which allows the creation of sonic presentational symbols of the whole experience. From this point of view, Diez-Fischer’s instrumental acousmatic music expands the limits of traditional acousmatic music by bringing it on stage and having it created directly by the musicians in front of the audience. For this reason, it makes sense to me to associate his music with the idea of the symbol proposed by Langer.

4. Signs of Touching

In Santiago Diez-Fischer’s music, the sense of touch is particularly solicited; on one hand, that of the musician, who, through sensory awareness of the materials, must recompose their instrumental gesture according to the sounds indicated in the score by the composer, and on the other, that of the listener, who, in order to fully understand this music, must bring to the surface their deepest experiences.

In order to make the listener’s experience resonate through the microscopic dimension of the rubbed and grained sounds, which produce vibrations at the limit of the acoustic and tactile experience, within which one is incorporated in a slow movement, discovering the surfaces of things, Diez-Fischer dilates the musical gestures; this dilation makes it possible to perceive micro-sound grains, elements hidden by the musicians in most cases. The microphoning of the instruments is used to make these sounds more distinctly perceived and to give an impression of proximity to matter. To perform this music, the performer must follow the movement drawn in the score with rigor and attention, touching the body of the instrument in a careful and precise manner. The musicians’ gestures, like discovery rituals, run through the sound bodies in a sensual way, digging into the instrument or the object used, as if they wanted to leave grooves on its surface. The experience of tracing movement and gesture over vibrating bodies is represented by the notation used by Diez-Fischer, who invented various signs to indicate how to touch the sound bodies.

The work on the duration and the continuous change in pressure, surface, and touch is not usually indicated by the signs of musical writing

6. Timbral indications have multiplied in the scores of 20th century composers, expanding into highly personal languages involving equally specific notations. With the rise in electronic music, the sound experience has expanded enormously, allowing us to listen in a completely different way and to produce sounds that would be impossible to produce otherwise. Amplification and microphone techniques, sound analysis, and electroacoustic treatment have made it possible to listen to microsounds [

19]

7. The experience of the interior of sound has been liberated by electronic music [

20] and is now part of the musicians’ technical background. This experience has progressively transferred into instrumental music, broadening the horizon of control of traditional musical parameters, expanding the types of sound composers can use. Among these, listening to the sonic grain, the long, almost timeless sounds, as if one wanted to stop the becoming, have become part of a great work of expressive deepening on the part of the musicians. In order to write this music, since the 1960s, composers have invented notations to indicate the type of movement to be made, but also to suggest a type of approach to sound that is free from tradition, linked to the control of the body in function of the precise reproduction of pitches and phrases and devoted to the masking of instrumental and performance defects. The prescription of movement has become so important for certain composers today that the writing is no longer sufficient, or even, in certain cases, no longer indicates the sonorous result

8. The gesture, the scene, the touch, the instrument, all have become important parameters in today’s music and a means of creating new sound experiences. The composer feels the need to interact with the listener and, through the listener, the social context itself, creating unexpected listening situations, which require the audience to become active, to break out of the passive role that usual musical listening imposes.

Musical writing then becomes a tool for rediscovering sound and instruments, going far beyond the notation of pitches and durations. It is a notation that has to be lived by the performer and that requires them to reinvent their movement, to rely on their primary, pre-musical, and pre-visual experience. The musician must learn to listen without seeing. It is no coincidence that in order to indicate the type of movement to be made to realize his music, Diez-Fischer makes videos, indicated in the score by links, in which he shows how to touch the instrument, rub it, extract distorted sounds from it. Diez-Fischer shows how to caress the sound body, to touch it: the tactile experience is the sound experience. The composer shows the gesture, the movement, how to grasp the sound body, and thus its material, its dimension, and its color. The indication of the movement to be made involves all the senses and gives an account of every detail thanks to the video recording. These videos, which film the composer himself, represent a remarkable advance in the writing; the integration of recorded material into the scores makes it possible to transmit the required movement in a precise manner; the recording situates the composer, gives body to the writing, and creates a new relationship between the presence of the gesture and its abstraction into the musical sign. In this way, the composer shows the sound, the way he touches the instrument, grasps the required object, and moves. The composer himself exists in the score in a more concrete way. He is there. This multimodal notation goes hand in hand with a performance that must be so in equal measure (

Figure 1).

5. Four Examples of Notation

In

Como sólo podían sus ojos (2013, rev. 2017) for flute, saxophone, piano, and electronic device, the composer asks the pianist to rub two plastic boxes

9 on the strings, in order to obtain an extremely complex, granulated sound, which bears little or no resemblance to the sound of a piano. In this piece, the instrument is used for its resonant and metallic qualities.

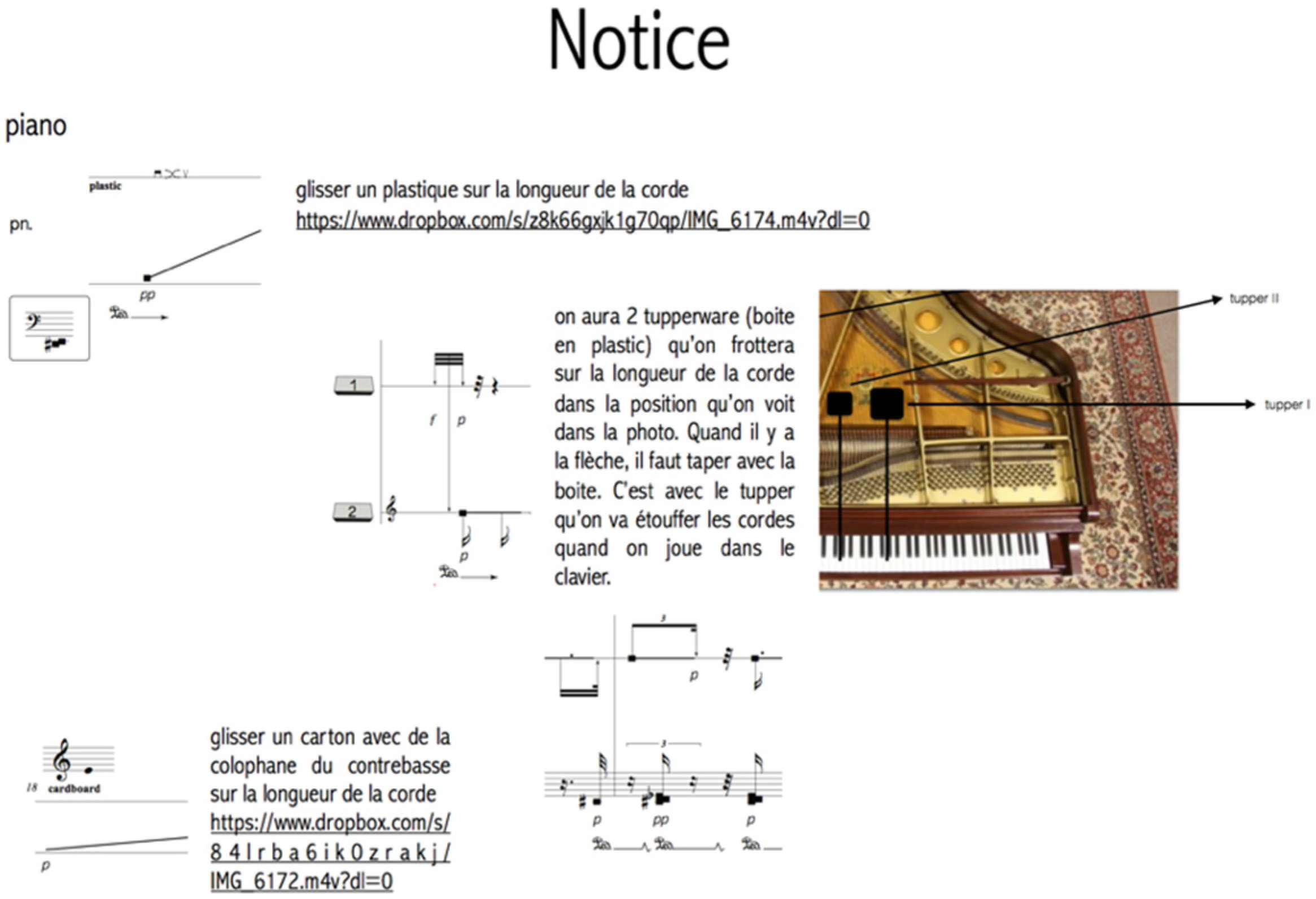

In the explanatory note of the piece at the beginning of the score, Diez-Fischer indicates how to realize the sounds required by the score (

Figure 2). The pianist has to provide themselves with two plastic boxes. The square head of the note indicates that the musician must rub the plastic on the strings; the photograph shows the regions of the piano where the box must be rubbed. In addition, the pianist must have a piece of cardboard that must be treated with double bass rosin. This treatment allows the cardboard to have a greater grip on the strings—just like a double bass bow on the strings of the instrument—and thus to set them vibrating with greater force. In the legend of the score, the composer also includes two links to videos in which he presents the technique (

Figure 1). The indications given allow the musician to reconstruct the movement necessary for the performance; the videos complete the graphic writing with visual and sound information. In this sense, the enrichment of the score with information that is not only graphic characterizes an augmented approach to writing, which allows the composer to be much more precise in indicating the desired sound.

In this piece, the flute and saxophone create with the piano a relaxed, dense, and violent texture, which makes one listen to the inside of the sound. The performers of winds caress the inside of the body of their instrument with their breath. The saxophone, without a mouthpiece, is blown in a unique position. The beginning of the piece, purely sonorous, textural, is characterized by a unique sonority lasting two minutes and thirty seconds. In this part, the instruments slightly resonate their bodies, creating a continuous sound, without beginning and without end, reminiscent of a cavernous sound, of a dark, silent place, of which the whole resonant space is perceived (

Figure 3).

The sound of the piece envelops the audience; it creates, with the electronics, an atmosphere of deep listening in which one is completely disoriented because one cannot predict the very duration of the sound. As in a mother’s womb, you are taken to places whose concreteness is sonorous and tactile rather than visual; you imagine the profile, you bet on a figure without being able to grasp it visually. These are sound bodies that one has to imagine, of tactile proximity, of which one does not perceive the contours and for this reason, they generate fear and also have the effect of shocking the unprepared listener. The very temporality of this music means that the timbre is in the foreground, where the invisible emerges with all its force. The vision of the musicians, motionless on stage, creates a semi-installative performance in which the musicians produce complex sounds with a minimum of movement

10. For this reason, the composer, in order to break the continuity, introduces gestural explosions such as blows and clashes, which articulate an otherwise uninterrupted music (

Figure 4)

11.

The type of gesture that the notation of the latter piece indicates is well summarized in the sign of the line, which defines a continuous movement, the internal articulation of which is left entirely to the performer. The apparent contradiction between the continuity of the line and the micro-discontinuity of the resulting sound reveals the importance of the musician’s gesture, touch, and flesh-and-blood movement.

In effect, Diez-Fischer is indicating something that cannot be written down in detail. Too many indications would be necessary and would detract from the spontaneity of the gesture. In this way, it is the musician who reinvents the sound following the composer’s instructions. The texture of the sound then emphasizes the timbre, as if one were touching a rough surface, as if the listener were touching the surfaces of the instruments himself and could directly experience the contact with the material.

In the piece

Oyelos desgarrar la tela del presagio (2016), for an ensemble of eleven instruments, Diez-Fischer deepens the relationship between touch, gesture, and sound. New indications appear, particularly in relation to the percussion part, which is characterized by the use of an electric guitar. The composer indicates four different types of pressure on the guitar: “a lot, scratch”, “pseudo scratch, slow bow”, “ordinary”, and “flute”. The first percussion part is to be played with the help of the following electric guitar pedals: whammy, distortion, pitch pedal, and volume as well as a double bass bow. In the explanatory link in the song legend, the composer shows the different techniques to be used on the instrument. These videos complete the notation and allow the interpreter to precisely understand the intention of the composer (

Figure 5).

In the frame shown in

Figure 5 of an extract from the video shown in the score, the composer shows how to perform a specific passage of the piece. The technique used must be performed at bar six, which can be seen notated in

Figure 6. In the score, the composer requires the percussionist to perform the passage by rubbing the guitar strings with a double bass bow, varying the pressure from “flautando” to “ordinario” to “a lot of pressure, scratch”. In addition, the bow must progressively move from the guitar fingerboard to the bridge.

The beginning of the piece is characterized by an extremely tense sonority, articulated by micro-sounds, with tenuous dynamics and a continuous, striated texture. The first percussionist plays a plastic box with a double bass bow. As in

Como sólo podían sus ojos, the atmosphere that sets in is that of deep listening, of discovery, of “cartomantic vision”, evoked by Olga Orozsco’s poem that gives the piece its title. The texture of this initial sound, made with a technique based on the rubbing of the sound body, defines an enveloping sonority, made of clashes, of matter. Once again, this sonority is indicated in an extremely synthetic way, requiring random movements from the musician. In this way, inner listening, as if perceived from the womb, is still evoked (

Figure 7).

The action is precisely notated. The bow of the double bass must rub the plastic box on the edge; the movement of the bow must be irregular and alternate between activity and silence using the heel. The playing time is indicated in seconds. As in the previous piece, a brutal, unprocessed sound occupies a time defined by a non-musical dimension. The chronometric time emphasizes the material, as if the very presence of the musician should abstract and become pure movement. Additionally, in this piece, the techniques of execution are shown by a video recording of the composer himself indicated in the legend of the score (

Figure 8).

These indications characterize the other instrumental parts, divided between wind instruments—flute, clarinet, trumpet and trombone—and strings—two violins, viola, cello and double bass. The tense, continuous sound that characterizes this texture is indicated by horizontal lines, which, as in the previous piece, are also characterized by great internal articulation left to the performer’s skill. The continuous line, the dynamics, and the movement on the sound body indicate the type of touch to be used.

The precision of the notation of continuous action, with micro-variations, particularly characterizes the piece

Plastic Disorder (2016), for amplified saxophone, percussion, and electronics. In the piece, physical contact with the surface of the instrument and touch are used to rub surfaces amplified by piezoelectric microphones, sound treatment pedals—distortion, whammy and volume; the percussion uses a tom-tom, plastic rulers of various lengths played with a double bass bow; a loudspeaker is positioned below the instrument in order to obtain a Larsen effect. The use of electronic instruments allows the composer to expand the tactile experience and to evoke it through the creation of sound frictions, a central element of Diez-Fischer’s language. In

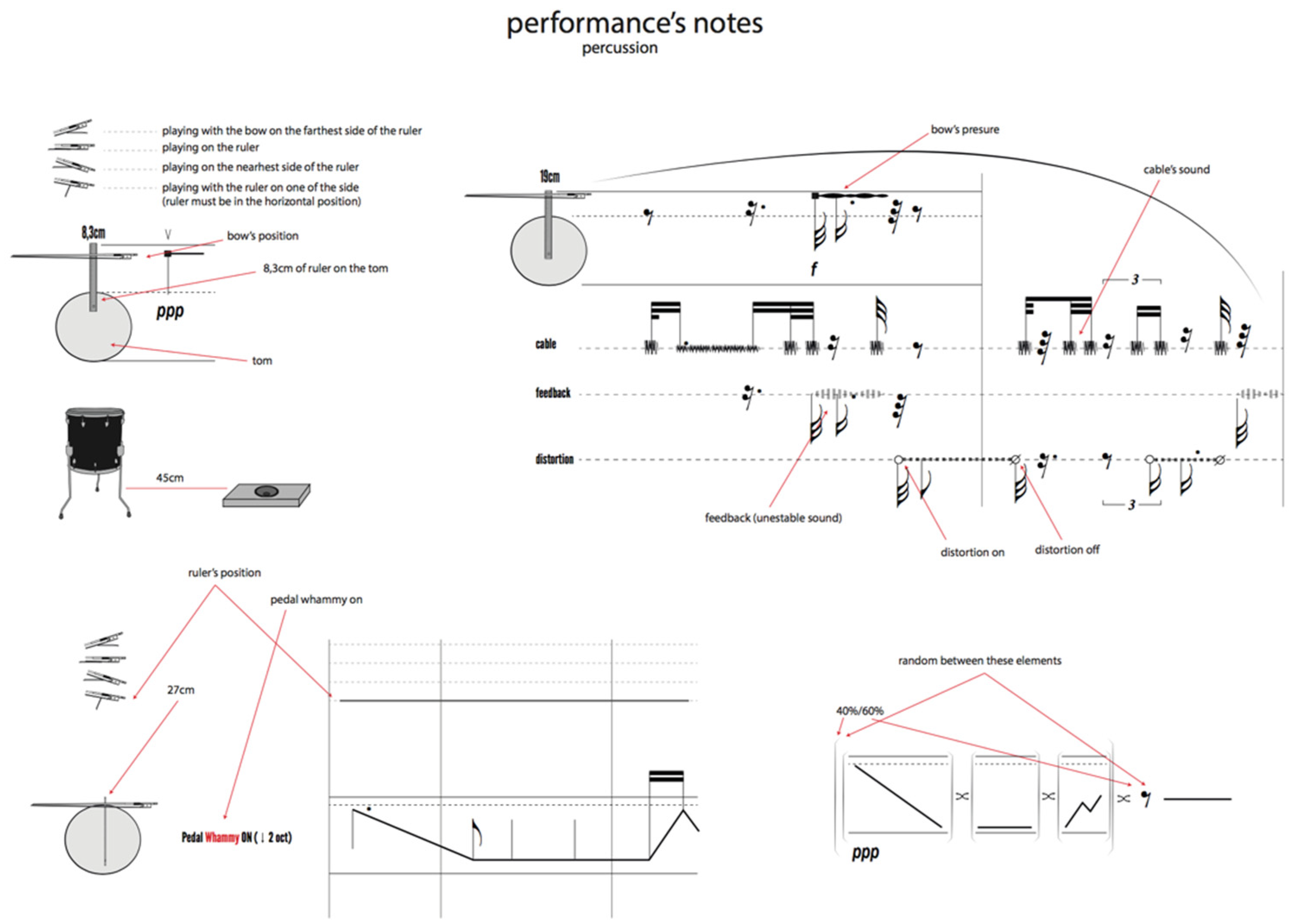

Plastic Disorder, the notation used for the percussion is singular and adds detail to those shown previously (

Figure 9).

In these instructions, the composer shows which instruments to use and how to touch them. In an extremely meticulous manner, Diez-Fischer describes the length of the ruler to be used to make the tom-tom membrane vibrate. In turn, the ruler is played by the double bass bow. The pressure of the bow is not indicated by dynamic variations, which are often used to indicate precise changes in the intensity of the pressure. This variation is indicated by a continuous line, which is thickened according to the desired pressure. The line represents the movement in time, the path on the body of the instrument and the pressure, unrelated to the dynamics (

Figure 10).

Here, the rubbing of the sound body is continuously controlled. The timbre, although soft, always written in a dynamic between pianissimo and piano, thickens according to the pressure exerted on the ruler. The intensity of the pressure is directly proportional to the width of the stroke. This indication shows the closeness between the pressure and the groove it would leave on a surface. The surface of the instrument, by vibrating, activates the Larsen effect re-injection process. This technical aspect means that the performance takes place within an atmosphere of extreme fragility, which can explode at any moment if control over the dynamics escapes the performers. The musician must control the touch and the sonic result. They must achieve a light and timorous, sometimes intense, caressing, which instead of exceeding the dynamics must go inside the surface, making grains appear deeper, modifying the pressure in order to obtain a thickening of the texture rather than the enlargement of the sound amplitude.

The reflection on the rubbing of the strings, the tension generated by the sound continuum and its depth continues in the piece

Plastic Pain Perception (2019), for electric guitar, accordion, and electronics. In this piece, the musician has to touch and run along the electric guitar fretboard. The slow and continuously changing movements define a constantly changing musical situation. The guitar part is particularly articulated in this sense. The instrument has to be played with different devices. First, the e-bow, whose proximity to the string modifies the dynamics of the sound as well as the harmonic richness of the sound spectrum; and second, the bottleneck, which allows the guitarist to create dense, moving sounds; in particular, slow glissandi that run entirely along the guitar fretboard (

Figure 11).

The

glissando, in the case of the example presented here, is extremely progressive; it gives the sensation of an extremely light touch on a smooth surface that escapes. Finally, the guitarist must equip themselves with a double bass bow. They need the bow to create a continuous, extremely taut sound, thanks to the slowness of the bow, which varies in the pressure on the string. This continuous movement invites the musician to feel the body of the guitar; the variation of pressure contrasts with the hieratic calm of the bow’s movement (

Figure 12).

The movement indicated is that of a caress that progressively modifies the intensity of its pressure. The tension that characterizes it emerges from the sense of discovery of something invisible and unknown, which is the interior of the sound body, which can only be experienced by provoking its vibration. Diez-Fischer’s music touches the instrument to resonate the sound body as such, just enough to hear it. In this piece, the change in pressure is also written with a more marked stroke.

Diez-Fischer translates the tactile experience into extremely sensitive music, similar to a hand running over an unfamiliar skin. The very sign of the line evokes such a path; the hand that touches a living, breathing surface does so in a certain time; the feeling of such an experience cannot be described in detail. Therefore, Diez-Fischer does it in the most objective way, using a chronometric time and a line. If the surface is round, or wavy or rough, it is the touch itself that tells; the line indicates a direction and a time. The rest is to be discovered. This line is then the actual tool for realizing the presentational symbol; it serves the composer to investigate a gesture and the musician to traverse a surface. The reading of the line, the understanding of the sound body to be known are the elements that prepare the sound production. They express it graphically just before becoming sound. This writing anticipates the gesture and moves the musician in the direction of sound production; is the actual symbol that expresses the tactile experience to the musician, telling them to reproduce it on their instrument. Langer is still useful for us to understand how writing and sound are connected.

6. The Line and the “Subvocal Singing”

Diez-Fischer’s work on the sound friction of resonant bodies is an expression of great sweetness, of a caress that can become a sinking into the body. The composer proposes extremely intimate listening, at the limits of the epidermal touch of objects. All the noises that emerge have a sense of fragility, of discovery, of the hand running across an unknown surface. The sudden bursts of this music sound like those that can suddenly occur inside a mother’s womb; as if the composer were imagining the sound in the womb of a future mother, in an underground, with the sounds of scrap metal, people, objects; you hear a sound, you feel a movement without being able to see what it is at all.

I believe that through his notations and sounds as well as through the audio-visual presentations that Diez-Fischer includes in the scores, the composer symbolically presents the dimension of touch; the instruments are in fact the means of a presentation of a sensitive experience close to that of touch, but also the notation. The signs used in the score are in this sense very indicative: these are the concrete signs of the expression of such a presentational symbol. They are lines indicating a surface, a slow and skillful trajectory to be traversed over a body. The body is often touched more deeply. In this case, the line becomes thicker, darker.

The fragility that this music often evokes suggests that the idea of touching unconsciously, as if one did not know what one was touching, is extremely present. The composer invites the listener into a dark space, full of microsounds, of fabrics whose material is unknown; in this way, he evokes “poetic images”, Gaston Bachelard would suggest [

7], of moments in which the listener must reactivate their deepest experience in order to interpret such music. The indications given by the composer in his scores show a continuous movement, which makes the caressing of the surface of the sound body being played as if the edges of that surface were invisible; it is a blind experience, which solicits listening and touch in an extreme way. This blind experience is analogous to the proprioceptive experience of touch, of touching as if from the inside.

In addition to sound, the sign directly appeals to the musician’s tactile experience. Observing the score, seeing the composer’s extremely detailed notations as well as their strangeness and originality make the musician have to reinvent the gesture that produces the sound, rethink the instrument and the approach to movement learned during their classical training. The line mark that characterizes Diez-Fischer’s music is the trace of a passage, a fissure, the memory of the past presence of someone unknown.

Two types of signs are worth noting: the straight line and the variation of this line, the one that thickens as it travels. The straight line obviously has no relation to the trajectory that the hand makes on a real surface. That is, there is no isomorphism between the line of the score and the shape of the instrument; whether it is a percussion touched with the hand or a ruler played with a double bass bow, the straight line remains the same. What is instead faithfully represented is time. The time of the action travels along an abstractly indicated trajectory and serves the musician to reconstruct the movement to be made. This movement, however, is not written down, it must be imagined entirely by the musician thanks to their instrumental knowledge and experience. Through this representation of the time of touch, the performer understands how to touch the sound body and the objects that the composer asks them to set into vibration. The performer has to understand and therefore invent a way to perform music whose notation is unconventional.

This reinvention, which takes place between the act of reading the score and its performance, is particularly characteristic of this notation of touch. The musician reads the score and internally thinks about the gesture to be performed. The reading of the score prepares the performance, the inward hearing prepares the musician’s gesture [

3]. Inner listening, that which makes the music heard by reading the sign on the score, activates the “tiny muscular responses of the breath and the vocal cords”, the “subvocal” singing, based on sound memories and lived experience as Langer suggests [

3]. The line indicates continuous movement; it requires the musician to reconstruct a gesture that cannot be completely prescribed by the score. The line represents the tempo of the movement, what is there from one point to another; the time segment indicates a touch that continues [

3]

12.

The imagination of the resulting sound passes through the gesture that produces the sound, which is the sensation of the sound in the muscles that produce it. The imagination is incomplete without this reference to the gesture [

3]. Vision is then overtaken and necessarily recalls the bodily experience, the invisible one, which belongs to every musician. This condition, which is common in music, is exacerbated by Diez-Fischer’s approach. Diez-Fischer’s music inserts itself in the space between the production of sound and its interpretation; it emerges from the “subvocal” experience, that which prepares the sound, but which is not yet fully so; it is itself a sign of a pre-musical experience, which prepares for listening. Notation and bodily movement are one and the same thing. This music then investigates movement and touch; through the use of caresses, it mobilizes the imagination in order to make sound and tactile experience live in a single sign-gesture.

7. Conclusions

In this text, I have interpreted certain pieces by the Argentinian composer Santiago Diez-Fischer in the light of the notion of presentational symbol. I have shown how this notion makes it possible to explain musical works by looking for their implicit meaning. On one hand, for Langer, this meaning is unconsumated and on the other hand, it can be understood but in a subtle way, understood as a message that cannot be translated into a real language. Fine. In this text, I have instead tried to indicate the implicit meaning of Santiago Diez-Fischer’s music by directing myself toward certain concrete examples extracted from his production. The hypothesis I developed first is that music results from a symbolic transformation of experience. This means that the composer under consideration transforms an experience. What experience? Specifically, that of touch. In order to understand this implicit meaning, I listened to Diez-Fischer’s music and focused on the communicated meaning. Listening to and reading the scores gave me an idea of his music, which I interpreted as the expression of tactile experience; an experience common to all and yet different for all.

This hypothesis is supported on one hand by the fact that the sound of his music is like that of rubbing, caressing, and hitting surfaces, and on the other hand, by the instrumental techniques that his notation prescribes to musicians. Instrumental techniques require the musician to stroke, rub, and press the instruments. The use of these techniques as well as the sound they produce are similar, if not often the same as the sound I perceive when I caress or lightly pass my hand over a fabric, or a skin: it is the sound of touch, of caress.

The notation of the caress or of listening inside the womb that these sounds evoke is written in a very particular way. Diez-Fischer’s scores rely on the writing of linear traces that serve to indicate movements conceived on the surfaces of the sound bodies. This notation evolves in the pieces I have considered; it gains in depth and detail, as if it were intended to indicate movement and tactile experience. The graphism of the line indicates a directionality on the surface of the sound body, but not only that, also a greater pressure, a path along the center or edge of the instrument. The composer indicates various ways of touching the sound body. The line itself suggests that the dimension of touch is synthesized in an extremely essential sign that mobilizes the musician’s internal experience. Without it, it would not be possible for these signs to indicate movements. I think that the movement that the line makes, one imagines, is itself a presentational symbol, which serves as a starting point for the performer’s reconstruction of the written music. I have defined this kind of moment in which the sound is imagined before being performed through the reading of the score as the “subvocal singing” of which Langer speaks; this singing is that which precedes the production of the sound, that which emerges between the reading and the first gesture produced. In a way, the line is already a symbol of the touch that the performer needs to move their own tactile experience before imitating it on the instrument. The line indicates a path; however, the matter and substance of such a path remain to be discovered by hand. This notation encourages the musician to discover a body and simultaneously generates music that presents such a path of discovery.

In conclusion, I have tried to indicate a way of interpreting Diez-Fischer’s music that shows how the notion of a presentational symbol is valid when the question of the meaning of a piece of music is asked; I tried to indicate an implicit import of this music. I think this notion is extremely valid. However, it requires an equally thorough method; it requires listening and in particular, it requires imagination on the part of the listener or researcher. The message we receive from this music is not explicitly stated by the composer, but can be grasped in various forms. Here, in this text, I have discussed an interpretation of such music. The tactile experience is at the center of this music, which presents it through extremely dark and noisy works. However, this dark color and sound are not threatening, but express an invisible experience, mainly involving the senses of touch and hearing, as if the listener was invited on a journey through the unknown.