The Phenomenology of Semiosis: Approaches to the Gap between the Encyclopaedia and the Porphyrian Tree Spanned by Sedimentation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Phenomenology as a Method in the Empirical Sciences

2.1. The Panoply of Methods: Modes of Access and Phenomena Accessed

2.2. The Zigzag between Phenomenology and Empirical Studies

Die Untersuchung bewegt sich gleichsam im Zickzack; und dieses Gleichnis paßt um so besser, als man, vermöge der innigen Abhängigkeit der verschiedenen Erkenntnisbegriffe, immer wieder zu den ursprünglichen Analysen zurückkehren und sie an den neuen, sowie die neuen an ihnen bewähren muß (Husserl [37] (p. 17); cf. Husserl [38] (p. 59)). (The investigation zigzags, as it were; and this comparison fits all the better since, due to the intimate dependency of the various concepts of knowledge, one must always return to the original analyses and prove them on the new ones, and vice versa. (My translation, as in the following quotes)).

Clearly such understanding is not possible unless the phenomenologist continues in some sense to live in the natural attitude that is being described. Presumably because it is impossible to live in the natural attitude and to observe it phenomenologically at the same time, Husserl often characterizes the pattern of investigation as a zigzag.

If any view like Dennett’s is right, cognitive psychology has been side-lined by framing the evolution of language through the lens of folk psychology. To the extent that folk psychology is a gadget that humans have collectively assembled to interpret one another, it seems unlikely that our own folk psychology is the best framework for describing the mechanisms of minds significantly different from those of contemporary humans ([46] (p. 23)).

2.3. Naturalization One Way or the Other

For Husserl, the task of phenomenological psychology is to investigate intentional consciousness in a non-reductive manner, that is, in a manner that respects its peculiarity and distinctive features. Phenomenological psychology is consequently a form of descriptive, eidetic, and intentional psychology which takes the first-person perspective seriously, but which—in contrast to transcendental phenomenology, that is, the true philosophical phenomenology—remains within a pre-philosophical attitude and stops short of effectuating the reflective move needed in order to attain the stance of transcendental philosophy [30] (p. 38).

Empirical science can present phenomenology with concrete findings that it cannot simply ignore, but must be able to accommodate; evidence that might force it to refine or revise its own analyses. At the same time, phenomenology might not only contribute with its own careful descriptions of the explanandum, but might also question and elucidate basic theoretical assumptions made by empirical science, just as it might aid in the development of new experimental paradigms [30] (p. 35).

3. The Semiotics of the Sign and Other Meanings

- There is a double asymmetry between the two parts, because one part, expression, is more directly experienced than the other;

- And because the other part, content, is more in focus than the other;

- These parts are differentiated from the point of view of the subjects involved in the semiotic process, even though they may not be so objectively, i.e., in the common sense, Lifeworld (except as signs forming part of that Lifeworld);

- This means that the two objects serving as expression and content do not go over into each over without rupture, contrary to what happens in perception;

- This also means that the two objects are experienced as pertaining to different categories of Lifeworld experience;

- The sign itself is subjectively differentiated from the referent, and the referent is more indirectly known than any part of the sign (as a general experience of the Lifeworld, not necessarily at the moment of experiencing the sign).

3.1. The Semiotics of Edmund Husserl

Die uneigentlichen Vorstellungen können nämlich: (1) als bloße Vermittler zur Erzeugung der ihnen korrespondierenden eigentlichen Vorstellungen dienen. In dieser Art funktionieren z. B. konventionelle Abzeichen, mnemotechnische Wortfolgen, mechanisch eingelernte Verse und dgl. (2) Die uneigentlichen Vorstellungen können aber auch als Surrogatvorstellungen die eigentlichen ersetzen [61] (p. 351). (The inappropriate ideas can, namely: (1) Serve as mere intermediaries for the production of the real ideas corresponding to them. Conventional emblems, mnemonic word sequences, mechanically learned verses, and the like, for example, function in this way. (2) The inauthentic ideas can, however, also as surrogate ideas, serve as replacements for the real ones).

daß irgendwelche Gegenstände oder Sachverhalte, von deren Bestand jemand aktuelle Kenntnis hat, ihm den Bestand gewisser anderer Gegenstände oder Sachverhalte in dem Sinne anzeigen, daß die Überzeugung von dem Sein der einen von ihm als Motiv (und zwar als ein nichteinsichtiges Motiv) erlebt wird für die Überzeugung oder Vermutung vom Sein der anderen (Husserl [37] (p. 25)). (that any objects or states of affairs, of the existence of which someone has current knowledge, indicate to him the existence of certain other objects or states of affairs in the sense that the conviction of the existence of one is experienced by him as a motive (and indeed as a not explicitly understood motive) for the belief or assumption of the existence of others.).

alle Ausdrücke in der kommunikativen Rede als Anzeichen fungieren. Sie dienen dem Hörenden als Zeichen für die „Gedanken” des Redenden, d. h. für die sinngebenden psychischen Erlebnisse desselben, sowie für die sonstigen psychischen Erlebnisse, welche zur mitteilenden Intention gehören (Husserl [37] (p. 33)). (all expressions in communicative speech function as indications. They serve the listener as a sign for the “thoughts” of the speaker, i.e., for the meaning-giving psychic experiences of the speaker, as well as for the other psychic experiences which belong to the communicating intention. (My translation)).

jede Rede und jeder Redeteil, sowie jedes wesentlich gleichartige Zeichen ein Ausdruck sei, wobei es darauf nicht ankommen soll, ob die Rede wirklich geredet, also in kommunikativer Absicht an irgendwelche Personen gerichtet ist oder nicht (Husserl [37] (p. 30f.)). (every kind of speech and every part of speech, as well as every essentially similar sign, being an expression, whereby it should not matter whether the speech is actually spoken, i.e., addressed to any person with communicative intention or not.).

3.2. Beyond the Surrogate Theory of the Sign

Die Bedeutungsfunktion ist nämlich nicht mehr nur Vorrecht des sprachlichen Ausdrucks: Husserl meint nun, daß man auch im Fall der Erinnerungszeichen, der Merkzeichen und der Signale usw. von echten Zeichen sprechen kann. Mit ihnen ist etwas gemeint, und zwar: “mit dem Stigma ist gemeint: Das ist ein Sklave. Mit der Fahne ist gemeint: Das ist ein deutsches Schiff. Mit dem Sturmsignal: Sturm ist im Anzug” (Ms. A I 17/II, BL. 57b). [83] (p. 192ff.) (The meaning function is to wit no longer only the prerogative of linguistic expression: Husserl now means that one can also speak of real signs in the case of reminders, markers, signals, etc. Something is meant by them, namely: “by the stigma is meant: This is a slave. The flag means: This is a German ship. With the storm signal: Storm is approaching”).

3.3. Signs and Appresentations

In general, we may state that in any appresentational situation the following four orders are involved: (a) the order of objects to which the immediately apperceived object belongs if experienced as a self, disregarding any appresentational references. We shall call this order the “apperceptual scheme.” (b) the order of objects to which the immediately apperceived object belongs if taken not as a self but as a member of an appresentational pair, thus referring to something other than itself. We shall call this order the “appresentational scheme.” (c) the order of objects to which the appresented member of the pair belongs which is apperceived in a merely analogical manner. We shall call this order the “referential scheme.” d) the order to which the particular appresentational reference itself belongs, that is, the particular type of pairing or context by which the appresenting member is connected with the appresented one, or, more generally, the relationship which prevails between the appresentational and the referential scheme. We shall call this order the “contextual or interpretational scheme.” [86] (p. 298).

Eine solche liegt schon in der äußeren Erfahrung vor, sofern die eigentlich gesehene Vorderseite eines Dinges stets und notwendig eine dingliche Rückseite appräsentiert, und ihr einen mehr oder minder bestimmten Gehalt vorzeichnet. Andrerseits kann es gerade dieße Art der schon die primordinale Natur mitkonstituierenden Appräsentation nicht sein, da zu ihr die Möglichkeit der Bewährung durch entsprechende erfüllende Präsentation gehört (die Rückseite wird zur Vorderseite), während das für diejenige Appräsentation, die in eine andere Originalsphäre hinein leiten soll, apriori ausgeschlossen sein muß [92] (p. 139). (Something like that is already present in external experience, insofar as the front side of a thing that is actually seen always and necessarily apprepresents a real back side and prescribes a more or less specific content for it. On the other hand, it cannot be question of precisely this type of appresentation, that is already co-constituted in primordial nature, since it includes the possibility of validation by means of a corresponding fulfilling presentation (the reverse side becomes the front side), while this must be excluded a priori for the appresentation that is intended to lead into another original sphere.).

3.4. Presentations, Representations, and Presentifications

4. From Relevancies to the Rhizome

4.1. Carneades at the Inn: The Case for Sedimentation

Ein Schema unserer Erfahrung ist ein Sinnzusammenhang unserer erfahrenden Erlebnisse, welcher zwar die in den erfahrenden Erlebnissen fertig konstituierten Erfahrungsgegenständlichkeiten erfaßt, nicht aber daß Wie des Konstitutionsvorganges, in welchem sich die erfahrenden Erlebnisse zu Erfahrungsgegenständlichkeiten konstituierten. Das Wie des Konstitutionsvorganges und dieser selbst bleibt vielmehr unbeachtet, das Konstituierte ist fraglos gegeben [104] (pp. 87f.). (A schema of our experience is a meaningful context in the experiences we live through, which indeed comprehends the experiential objects as being fully constituted in the experiences encountered, but not the How of the constitutional process in which the experiences constituted gone through are constituted as experiential objects. Rather, the How of the process of constitution and the process as such remain unnoticed; what is constituted is unquestionably given.).

4.2. A Protracted Stay at the Inn: Signs and Meanings

4.3. Eco’s Encyclopaedia and the Semantic Field

Principes de connexion et d’hétérogénéité: n’importe quel point d’un rhizome peut être connecté avec n’importe quel autre, et doit l’être. C’est très différent de l’arbre ou de la racine qui fixent un point, un ordre. L’arbre linguistique à la manière de Chomsky commence encore à un point S et procède par dichotomie. Dans un rhizome au contraire, chaque trait ne renvoie pas nécessairement à un trait linguistique: des chaînons sémiotiques de toute nature y sont connectés à des modes d’encodage très divers, chaînons biologiques, politiques, économiques, etc., mettant en jeu non seulement des régimes de signes différents, mais aussi des statuts d’états de choses [118] (p. 13). (Principles of connection and heterogeneity: any point of a rhizome can be connected with any other, and so it must be. It is very different from the tree or the root which fixes a point, an order. The linguistic tree in the manner of Chomsky again begins at a point S and proceeds by dichotomy. In a rhizome, on the contrary, each feature does not necessarily refer to a linguistic feature: semiotic links of all kinds are connected there to very diverse modes of encoding, biological, political, economic links, etc., involving not only different sign regimes, but also statuses of states of affairs.).

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | As Spiegelberg [3] (p. 9) points out, Husserl mentioned having tried out the methods of experimental psychology pioneered by the Würzburg school. But the notion of experiment in the Würzburg school is different from what is, nowadays, understood by that term: it involved systematic self-observation. |

| 4 | Aristotle certainly has a lot to say also about what we have, following Deely, called the Stoic notion of sign. Most of the time, however, Aristotle uses the term symbolon to indicate the linguistic sign, but the terms semeîon and tekmerion to indicate the inference. See Manetti [76] (p. xiv, 56, 70f., 72, 74, 77ff.). In fact, Karl Bühler [143] (p. 185f.) actually attributes what Deely calls the Augustinean notion to Aristotle. |

| 5 | In Husserl [144] (p.441), we read that “der Ausdruck ist appräsentierend, das Ausgedrückte ist mitdaseiend”. But since, again, this is about the experience of the other subject, it is rather the terms “Ausdruck” and “Ausgedrückte” which are inappropriately used here. In Sonesson [19] (pp. 220ff.), I am guilty of using appresentation in the same misleading way as Schütz and Luckmann. |

References

- Husserl, E. Philosophie der Arithmetik: Mit Ergänzenden Texten (1890–1901); Martinus Nijhoff: Haag, The Netherlands, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, E. Phänomenologische Psychologie: Vorlesungen Sommersemester 1925; Martinus Nijhoff: Haag, The Netherlands, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegelberg, H. Phenomenology in Psychology and Psychiatry: A Historical Introduction; Northwestern U.P.: Evanston, IL, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegelberg, H. The Phenomenological Movement: A Historical Introduction; Martinus Nijhoff: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1965–1969; Volume 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, B.C. Derrida’s reading of Husserl in Speech and Phenomena: Ontologism and the metaphysics of presence. Husserl Stud. 1985, 2, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowell, S.G. Husserl, Derrida, and the phenomenology of expression. Philos. Today 1996, 40, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonesson, G. Mastering phenomenological semiotics with Husserl and Peirce. In Semiotics and its Masters; Bankov, K., Cobley, P., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Sonesson, G. Phenomenology meets Semiotics: Two Not So Very Strange Bedfellows at the End of their Cinderella Sleep. Metodo 2015, 3, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sonesson, G. The Elucidation of the Phenomenology of the Picture Sign from its Phaneroscopy, and vice versa. In Phaneroscopy and Phenomenology: A Neglected Chapter in the History of Ideas; Pietarinen, A.-V., Shafiei, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany.

- Sonesson, G. New considerations on the proper study of man—and, marginally, some other animals. Cognitive Semiotics 2009, 4, 133–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sonesson, G. The view from Husserl’s lectern: Considerations on the role of phenomenology in cognitive semiotics. Cybern. Hum. Knowing 2009, 16, 107–148. [Google Scholar]

- Sonesson, G. Beyond methods and models. Semiotics as a distinctive discipline and an intellectual tradition. Signs-Int. J. Semiot. 2008, 2, 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Sonesson, G. Semiotics inside-out and/or outside-in: How to understand everything and (with luck) influence people. Signata Ann. Des Sémiotiques/Ann. Semiotics 2011, 2, 315–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sonesson, G. The mirror in-between picture and mind: A phenomenologically inspired approach to cognitive semiotics. Chin. Semiot. Stud. 2015, 11, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonesson, G.; Lenninger, S. The psychological development of semiotic competence: From the window to the movie by way of the mirror. Cogn. Dev. 2015, 36, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonesson, G. The cognitive semiotics of the picture sign. In Visual Communication; Machin, D., Ed.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 23–50. [Google Scholar]

- Sonesson, G. La sémiotique cognitive: Le même et l’autre de la sémiotique structurale. In La Sémiotique et Son Autre; Biglari, A., Roelens, N., Eds.; L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2019; pp. 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Sonesson, G. The Phenomenological Road to Cognitive Semiotics. Culture of Communication/Communication of Culture—Comunicación de la cultura/Cultura de la Comunicación. In Proceedings of the 10th World Congress of the International Association for Semiotic Studies (IASS/AIS), La Coruña, Spain, 22–26 September 2009; Couto Cantero, P., Enríquez Veloso, G., Passeri, A., Paz Gago, J.M., Eds.; Universidade de Coruña: A Coruña, Spain, 2012; pp. 855–866. [Google Scholar]

- Sonesson, G. The foundation of cognitive semiotics in the phenomenology of signs and meanings. Intellectica 2012, 58, 207–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonesson, G. Nothing human is foreign to me—except some of it. From the semiotic tradition to cognitive semiotic by the way of phenomenology. Degrés 2021, 186–187, b1-b23. [Google Scholar]

- Sonesson, G. Cognitive Science and Semiotics. In Bloomsbury Semiotics; Volume 4 Semiotic Movements, Pelkey, J., Cobley, P., Eds.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2022; pp. 293–312. [Google Scholar]

- Zlatev, J. Cognitive semiotics. In International Handbook of Semiotics; Trifonas, P.P., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 1043–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Sonesson, G. The pronominalization of culture. Dyadic and triadic models of interculturality. Les signes du monde: Intercultralte & Globalisation. In Proceedings of the IASS-AIS Conference, Lyon, France, 7–12 July 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dennett, D.C. Who’s on First? Heterophenomenology Explained. J. Conscious. Stud. 2003, 10, 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sonesson, G. Steps towards an epistemology for cognitive semiotics. In Proceedings of the Fourth Conference on Epistemology of Association of Ancient Greek Philosophy ‘syn Athena’, Kavala, Greece, 3–5 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gutland, C. Husserlian Phenomenology as a Kind of Introspection. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schwitzgebel, E. Introspection. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Zalta, E.N., Ed.; Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, E. Aufsätze und Vorträge (1911–1921); Martinus Nijhoff: Haag, The Netherlands, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, E. Ideen zu einer reinen Phänomenologie und phänomenologischen Philosophie. In Volume Buch 3: Die Phänomenologie und die Fundamente der Wissenschafte; Martinus Nijhoff: Haag, The Netherlands, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Zahavi, D. Naturalized Phenomenology: A Desideratum or a Category Mistake? R. Inst. Philos. Suppl. 2013, 72, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, S.; Brøsted Sørensen, J. Experimenting with phenomenology. Conscious. Cogn. 2006, 15, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurwitsch, A. Edmund Husserl’s Conception of Phenomenological Psychology. Rev. Metaphys. 1966, 19, 689–727. [Google Scholar]

- Sonesson, G. Pictorial Concepts. Inquiries into the Semiotic Heritage and its Relevance for the Analysis of the Visual World; Lund University Press: Lund, Sweden, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Les sciences de l’homme et la phénoménologie (I à IV). Bull. De Psychol. 1951, 394–404. Available online: https://www.persee.fr/doc/bupsy_0007-4403_1964_num_18_236_7457?q=Les+sciences+de+l%27homme+et+la+phénoménologie+ (accessed on 7 October 2022). [CrossRef]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Parcours Deux: 1951–1961; Verdier: Paris, France, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Orth, E.W. Edmund Husserls “Krisis der Europäischen Wissenschaften und die Transzendentale Phänomenologie”: Vernunft und Kultur; Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft: Darmstadt, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, E. Logische Untersuchungen. Band II, Teil 1: Untersuchungen sur Phänomenologie und Theorie der Erkenntnis; Max Niemeyer: Tübingen, Germany, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, E. Die Krisis der europäischen Wissenschaften und die Transzendentale Phänomenologie: Eine Einleitung in die Phänomenologische Philosophie; Martinus Nijhoff: Haag, The Netherlands, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, E. Die Krisis der europäischen Wissenschaften und die Transzendentale Phänomenologie, Ergänzungsband, Texte aus dem Nachlass 1934–1937; Kluwer: Dordrecht, Germany, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Phénoménologie de la Perception; Gallimard: Paris, France, 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Psychologie et Pédagogie de l’enfant. Cours de Sorbonne 1949–1952; Verdier: Lagrasse, France, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Merleau-Ponty à la Sorbonne. Bull. De Psychol. 1964, 236, 1–336. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, D. The Paradox of Subjectivity: The Self in the Transcendental Tradition; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Churchland, P. Folk Psychology and the Explanation of Human Behavior. Philos. Perspect. 1989, 3, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonesson, G. Considerations on the subtle art of integrating linguistics (and/or semiotics). In Eugenio Coseriu: Past, Present and Future; Willems, K., Munteanu, C., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2021; pp. 151–164. [Google Scholar]

- Planer, R.J.; Sterelny, K. From Signal to Symbol: The Evolution of Language; The MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sonesson, G. The act of interpretation. A view from semiotics. Galáxia 2002, 4, 67–99. [Google Scholar]

- Sonesson, G. The signs of life in society—And out if. Sign Syst. Stud. 1999, 27, 88–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonesson, G. New Reflections on the Problem(s) of Relevance. In Relevance and Irrelevance: Theories, Factors and Challenges—Theories, Factors and Challenges; Strassheim, J., Nasu, H., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 21–50. [Google Scholar]

- Petitot, J.; Varela, F.J.; Pachoud, B.; Roy, J.-M. Naturalizing Phenomenology: Issues in Contemporary Phenomenology and Cognitive Science; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Zahavi, D. Phenomenology and the project of naturalization. Phenomenol. Cogn. Sci. 2004, 3, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tieszen, R. Gödel’s Path from the Incompleteness Theorems (1931) To Phenomenology (1961). Bull. Symb. Log. 1998, 4, 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonesson, G. Tecken och Handling. Från Språkhandlingen till Handlingens Språk; Doxa: Lund, Sweden, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, S. Phenomenology and Experimental Design. Toward a Phenomenologically Enlightened Experimental Science. J. Conscious. Stud. 2003, 10, 85. [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, A. Toward a neurophenomenology as an account of generative passages: A first empirical case study. Phenomenol. Cogn. Sci. 2002, 1, 133–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramstead, M.J.D.; Seth, A.K.; Hesp, C.; Sandved-Smith, L.; Mago, J.; Lifshitz, M.; Pagnoni, G.; Smith, R.; Dumas, G.; Lutz, A.; et al. From generative models to generative passages: A computational approach to (neuro) phenomenology. Rev. Philos. Psychol. 2022, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonesson, G. From the meaning of embodiment to the embodiment of meaning: A study in phenomenological semiotics. In Body, Language and Mind; Volume 1: Embodiment, Zienke, T., Zlatev, J., Frank, R.M., Eds.; Mouton de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2007; pp. 85–128. [Google Scholar]

- Sonesson, G. Semiosis and the elusive final interpretant of understanding. Semiotica 2010, 179, 145–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonesson, G. The semiotic function and the genesis of pictorial meaning. In Center/Periphery in Representations and Institutions. In Proceedings of the 3rd Annual Meeting and Congress of The International Semiotics Insitute, Imatra, Finland, 16–21 July 1990; Tarasti, E., Ed.; International Semiotics Institute: Kaunas, Lithuania, 1992; pp. 211–256. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, E. Aufsätze und Rezensionen (1890–1910); Martinus Nijhoff: Haag, The Netherlands, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, E. Zur Logik der Zeichen (Semiotik). In Philosophie der Arithmetik: Mit Ergänzenden Texten (1890–1901). Husserliana: Gesammelte Werke. Bd 12; Eley, L., Ed.; Martinus Nijhoff: Haag, The Netherlands, 1970; pp. 340–373. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, T. Surrogates and Empty Intentions: Husserl’s ‘On the Logic of Signs’ as the Blueprint for His First Logical Investigation. Husserl Stud. 2017, 33, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, T. Husserl’s Early Semiotics and Number Signs: Philosophy of Arithmeticthrough the Lens of “On the Logic of Signs (Semiotic)”. J. Br. Soc. Phenomenol. 2017, 48, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuh, D. How do categorial representations influence everyday intuition? On Husserl’s early attempt to grasp the horizontal structure of consciousness. Studia Univ. Babes-Bolyai-Philos. 2008, 53, 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Zuh, D. Wogegen wandte sich Husserl 1891? Husserl Stud. 2012, 28, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majolino, C. Structure de l’indice et équivocité du signe. A l’origine du partage Anzeigen/Ausdrucken dans les Recherches logiques. Hist. Épistémologie Lang. 2010, 32, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesalli, L.; Majolino, C.; Dire et vouloir dire: Philosophies du langage et de l’esprit du Moyen Âge à l’époque contemporaine: Présentation. Methodos 2014, 14. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/methodos/4090 (accessed on 7 October 2022).

- Ierna, C. Husserl and the infinite. Studia Phaenomenologica 2003, 3, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ierna, C. The Beginnings of Husserl’s Philosophy, Part 1: From Über den Begriff der Zahl to Philosophie der Arithmetik. New Yearb. Phenomenol. Phenomenol. Philos. 2005, 5, 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ierna, C. The Beginnings of Husserl’s Philosophy, Part 2: Philosophical and Mathematical Background. New Yearb. Phenomenol. Phenomenol. Philos. 2006, 6, 33–81. [Google Scholar]

- Deely, J.N. Introducing Semiotic: Its History and Doctrine; Indiana U.P.: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Deely, J.N. Augustine & Poinsot: The Protosemiotic Development; University of Scranton Press: Scranton, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Deely, J.N. Medieval Philosophy Redefined: The Development of Cenoscopic Science, AD 354 to 1644 (From the Birth of Augustine to the Death of Poinsot); University of Scranton Press: Scranton, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Deely, J.N. Four Ages of Understanding: The First Postmodern Survey of Philosophy from Ancient Times to the Turn of the Twenty-First Century. University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sonesson, G. Meaning redefined: Reflections on the scholastic heritage conveyed by john deely to contemporary semiotics. Am. J. Semiotics 2018, 34, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manetti, G. Theories of the Sign in Classical Antiquity; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sonesson, G. Semiosis and Sedimentation. From the Translation of Culture to the Culture of Translation. In Differences, Similarities and Meanings. Semiotic Investigations of Contemporary Communication Phenomena; Dragan, N.-S., Ed.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2021; pp. 97–120. [Google Scholar]

- Cesalli, L.; Majolino, C. Making Sense. On the Cluster significatio-intentio in Medieval and “Austrian” Philosophies. Methodos 2014, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrida, J. La Voix et le Phénomène: Introduction au Problème du Signe Dans la Phénoménologie de Husserl; PUF: Paris, France, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobson, R. Coup d’oeil sur le développement de la sémiotique. In A Semiotic Landscape: Panorama Sémiotique; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 1979; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sokolowski, R. Husserlian Meditations; Northwestern University Press: Evanston, IL, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Sokolowski, R. Presence and Absence: A Philosophical Investigation of Language and Being; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Sinigaglia, C. Zeichen und Bedeutung. Zu einer Umarbeitung der Sechsten Logischen Untersuchung. Husserl Stud. 1998, 179–217. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, E. Logische Untersuchungen. Ergänzungsband. Zweiter Teil. Texte für die Neufassung der VI. Untersuchung. Zur Phänomenologie des Ausdrucks und der Erkenntnis (1893/94-1921); Melle, U., Ed.; Kluwer Academie Publishers: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2005; p. 80. [Google Scholar]

- Deely, J.N. New Beginnings: Early Modern Philosophy and Postmodern Thought; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Schütz, A. Collected Papers 1 The Problem of Social Reality; Martinus Nijhoff: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Schütz, A. Symbol, reality and society. In Collected Papers 1 The Problem of Social Reality; Natanson, M., Ed.; Martinus Nijhoff: Haag, The Netherlands, 1962; pp. 287–356. [Google Scholar]

- Luckmann, T. Lebenswelt und Gesellschaft: Grundstrukturen und Geschichtliche Wandlungen; Schöningh: Paderborn, Germany, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, E. Erfahrung und Urteil: Untersuchungen zur Genealogie der Logik; Claasen: Hamburg, Germany, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, E. Ideen zu Einer Reinen Phänomenologie und Phänomenologischen Philosophie. In Buch 1: Allgemeine Einführung in die Reine Phänomenologie; Martinus Nijhoff: Haag, The Netherlands, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, E. Formale und Transzendentale Logik: Versuch Einer Kritik der Logischen Vernunft; Martinus Nijhoff: Haag, The Netherlands, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, E. Cartesianische Meditationen und Pariser Vorträge; Martinus Nijhoff: Haag, The Netherlands, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Moran, D.; Cohen, J.D. The Husserl Dictionary; Continuum: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond, J.J. The A to Z of Husserl’s Philosophy; Scarecrow Press: Plymouth, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, E. Phantasie, Bildbewusstsein, Erinnerung: Zur Phänomenologie der Anschaulichen Vergegenwärtigungen: Texte aus dem Nachlass (1898–1925); Martinus Nijhoff: Haag, The Netherlands, 1980. [Google Scholar]

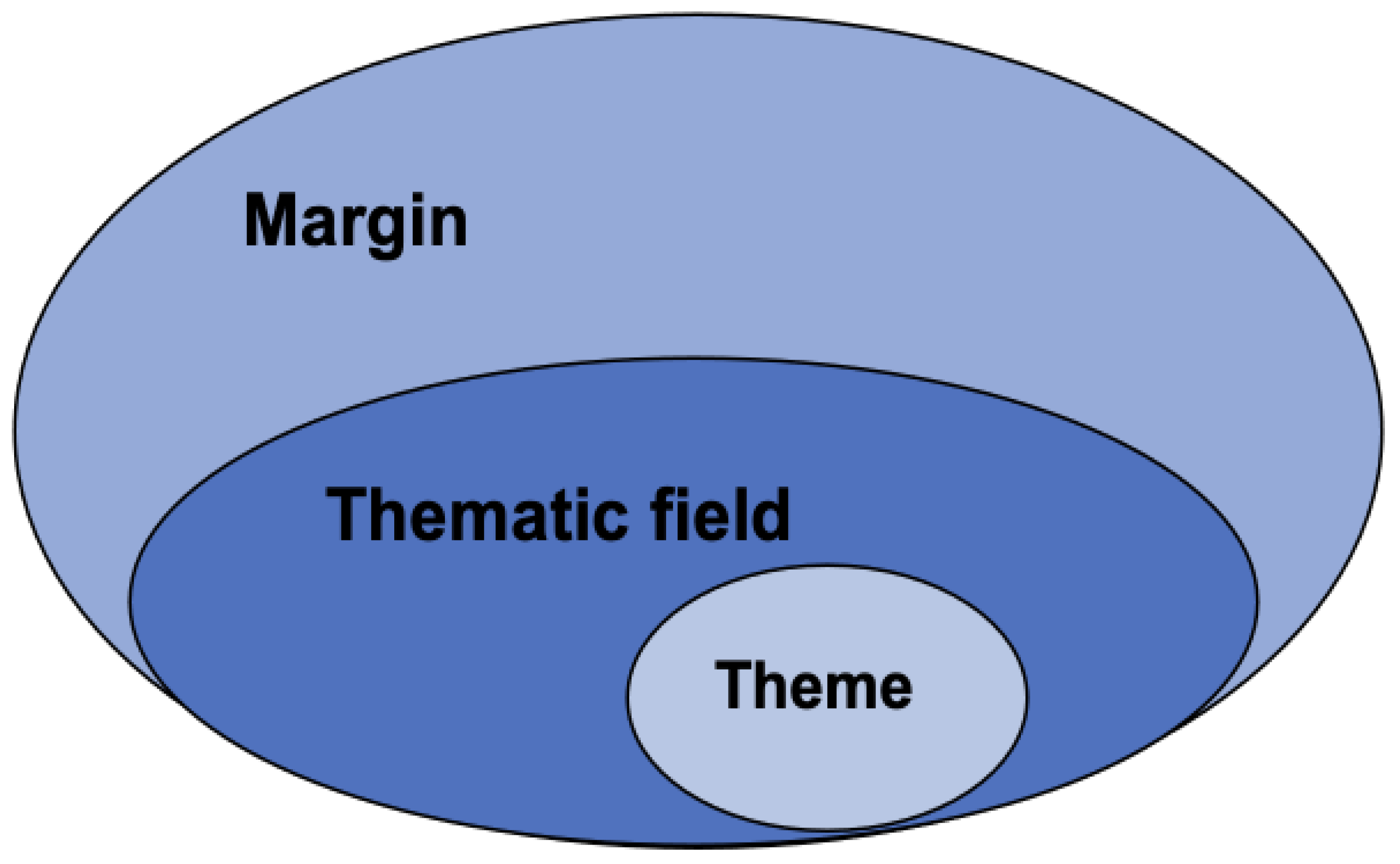

- Gurwitsch, A. The Field of Consciousness; Duquesne, U.P.: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J.J. A prefatory essay on the perception of surfaces versus the perception of markings on a surface. In The Perception of Pictures. Vol. 1, Alberti’s Window: The Projective Model of Pictorial Information; Hagen, M.A., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1980; pp. xi–xvii. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J.J. The Ecological Approach to the Visual Perception of Pictures. Leonardo 1978, 11, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sonesson, G. The Mind in the Picture and the Picture in the Mind: A Phenomenological Approach to Cognitive Semiotics. Lexia: Riv. Di Semiot 2011, 07/08, 167–182. [Google Scholar]

- Sperber, D.; Wilson, D. Relevance: Communication and Cognition; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1986; Second Edition: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Strassheim, J.; Nasu, H.E. Relevance and Irrelevance: Theories, Factors and Challenges—Theories, Factors and Challenges; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schütz, A. Reflections on the Problem of Relevance; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Grice, P. Studies in the Way of Words; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schütz, A. Der Sinnhafte Aufbau der Sozialen Welt: Eine Einleitung in die Verstehende Soziologie; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, E. Zur Phänomenologie der Intersubjektivität; Volume T. 1: 1905–1920: Texte aus dem Nachlass, Martinus Nijhoff: Haag, The Netherlands, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, E. Zur Phänomenologie der Intersubjektivität; Volume T. 2: 1921–1928: Texte aus dem Nachlass, Martinus Nijhoff: Haag, The Netherlands, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, E. Zur Phänomenologie der Intersubjektivität; Volume 3 1929–1935: Texte aus dem Nachlass, Martinus Nijhoff: Haag, The Netherlands, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Welton, D. The Other Husserl: The Horizons of Transcendental Phenomenology; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Steinbock, A.J. Home and beyond: Generative Phenomenology after Husserl; Northwestern University Press: Evanston, IL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gurwitsch, A. Théorie du Champ de la Conscience; Desclée de Brouwer: Paris, France, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Dessalles, J.-L. Aux Origines du Langage: Une Histoire Naturelle de la Parole; Hermès Science: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gurwitsch, A. Marginal Consciousness; Ohio University Press: Athens, OH, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Zlatev, J.; Zywiczynski, P.; Wacewicz, S. Pantomime as the original human-specific communicative system. Cogn. Semiot. 2020, 5, 156–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlatev, J.; Wacewicz, S.; Zywiczynski, P.; van de Weijer, J. Multimodal-first or pantomime-first? Communicating events through pantomime with and without vocalization. Interact. Stud. 2017, 18, 465–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eco, U. Intellectual autobiography of Umberto Eco. In The philosophy of Umberto Eco; Beardsworth, S., Auxier, R.E., Eds.; Open Court: Chicago, IL, USA, 2017; pp. 3–66. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, U. From the Tree to the Labyrinth: Historical Studies on the Sign and Interpretation; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, U. Den Frånvarande Strukturen: Introduktion till den Semiotiska Forskningen; Cavefors: Staffanstorp, Sweden, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, G.; Guattari, F. Capitalisme et Schizophrénie. Tome 2, Mille Plateaux; Éditions de Minuit: Paris, France, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Diodato, F. La théorie des champs lexicaux: En essai de sémantique saussurenne? Cah. Ferdinand De Saussure 2018, 71, 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Coseriu, E. Principios de Semántica Estructural; Gredos: Madrid, Spain, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Geckeler, H. Strukturelle Semantik und Wortfeldtheorie; Fink: München, Germany, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Geeraerts, D. Theories of Lexical Semantics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, J. Semantics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1977; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer, A.; Kittay, E.F. Introduction. In Frames, Fields, and Contrasts: New Essays in Semantic and Lexical Organization; Lehrer, A., Kittay, E.F., Eds.; Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1992; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Koestler, A. The Act of Creation; Hutchinson: London, UK, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Sonesson, G. On the Borders of Metaphorology: Creativity Beyond and Ahead of Metaphors. In “La Izvoarele Imaginației Creatoare”. Studii și Evocări în Onoarea Profesorului Mircea Borcilă; Faur, E., Feurdean, D., Pop, I., Eds.; Editura Argonaut & Casa Cărții de Știință: Cluj-Napoca, Romania.

- Lakoff, G.; Johnson, M. Philosophy in the Flesh: The Embodied Mind and its Challenge to Western Thought; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sonesson, G. On pictorality. The impact of the perceptual model in the development of visual semiotics. In The Semiotic Web 1992/93: Advances in Visual Semiotics; Sebeok, T., Umiker-Sebeok, J., Eds.; Mouton de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 1995; pp. 67–108. [Google Scholar]

- Sonesson, G. An essay concerning images: From rhetoric to semiotics by way of ecologićal physics. Semiotica 1996, 109, 41–140. [Google Scholar]

- Sonesson, G. From Semiosis to Ecology. On the theory of iconicity and its consequences for the ontology of the Lifeworld. VISIO 2001, 6, 85–110. [Google Scholar]

- Sonesson, G. The phenomenological semiotics of iconicity and pictoriality—including some replies to my critics. Lang. Semiot. Stud. 2016, 2, 1–73. [Google Scholar]

- Violi, P. Encyclopedia: Criticality and Actuality. In The Philosophy of Umberto Eco; Beardsworth, S., Auxier, R.E., Eds.; Open Court: Chicago, IL, USA, 2017; pp. 223–250. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, U. Interpretation and Overinterpretation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobson, R. The dominant. In Readings in Russian Poetics: Formalist and Structuralist Views; Pomorska, K., Matejka, L., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1971; pp. 82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Armesto, F. Amerigo: The Man Who Gave His Name to America; Phoenix: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Brummett, P.J. The ’Book’ of Travels: Genre, Ethnology, and Pilgrimage, 1250–1700; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, M.B. The Witness and the Other World: Exotic European Travel Writing, 400–1600; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Groesen, M.V. The Representations of the Overseas World in the De Bry Collection of Voyages (1590–1634); Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rubieś, J.-P. Travel and Ethnology in the Renaissance: South India through European Eyes, 1250–1625; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sonesson, G. Approximations to the Genuine Dialectics of the Enlightenment. On Husserl’s Europe, “Social Justice Theory”, and the Ethics of Semiosis. Lang. Semiotic Studies 2021, 3, 6–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sonesson, G. What Is Social and What Is Mediated in “Social Media”? Further Considerations on the Cognitive Semiotics of Lifeworld Mediations. Int. J. Semiot. Vis. Rhetor. 2020, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanigan, R. Speaking and Semiology: Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenological Theory of Existential Communication; Mouton: Hague, Paris; Hawthorne, NY, USA, 1972; 2nd Reprint Edition, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bühler, K. Sprachtheorie. Die Darstellungsfunktion der Sprache; Ullstein: Berlin, Germany, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Husserl, E. Ideen zu Einer Reinen Phänomenologie und Phänomenologischen Philosophie. In Buch 2: Phänomenologische Untersuchungen zur Konstitution; Martinus Nijhoff: Haag, The Netherlands, 1952. [Google Scholar]

| Phenomena accessed | ||||

| Ipseity (First person) | Dialogicity (Second person) | Neutrality/Objectivity (Third person) | ||

| Modes of access | Ipseity (First person) | Introspection | Empathy | Phenomenology |

| Dialogicity (Second person) | Participant observation | Dialogue, Interview | Participant observation | |

| Neutrality/ Objectivity (Third person) | Behaviouristic description, “hetero-phenomenology” | Interview, Questionnaire | Experimentation Detached observation Brain imagining Computational modelling | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sonesson, G.H. The Phenomenology of Semiosis: Approaches to the Gap between the Encyclopaedia and the Porphyrian Tree Spanned by Sedimentation. Philosophies 2022, 7, 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies7050114

Sonesson GH. The Phenomenology of Semiosis: Approaches to the Gap between the Encyclopaedia and the Porphyrian Tree Spanned by Sedimentation. Philosophies. 2022; 7(5):114. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies7050114

Chicago/Turabian StyleSonesson, Göran H. 2022. "The Phenomenology of Semiosis: Approaches to the Gap between the Encyclopaedia and the Porphyrian Tree Spanned by Sedimentation" Philosophies 7, no. 5: 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies7050114

APA StyleSonesson, G. H. (2022). The Phenomenology of Semiosis: Approaches to the Gap between the Encyclopaedia and the Porphyrian Tree Spanned by Sedimentation. Philosophies, 7(5), 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies7050114