Abstract

Authors create fictional characters; that is a “creationist locution”. Artefactualism takes such statements very seriously and holds that fictional characters are abstract artefacts, i.e., entities that are both created and abstract. Anti-creationists, by contrast, deny that we need to postulate such doubtful entities to explain creationist locutions. In this paper, I present this debate in the form of a paradox, which organises the many existing theories of creationist locutions in a single logical space. This new way of framing the problem displays the crucial role of so-called “linking principles”. In general, it seems that fictionality entails nonexistence, while creation entails existence. This is why “fictional creatures” are puzzling. I further argue that to create means to invent and to realise, and finally, that fictional characters are invented but not created, contra artefactualism. I thus advocate for a new kind of anti-creationism about fictional characters.

1. Creationism in the Philosophy of Fiction

In [1] (p. 144), Lamarque and Olsen write the following passage:

Who created Frankenstein’s monster? One answer, from the internal perspective, is of course: Frankenstein. Only from the external point of view must the reply be: Mary Shelley.

This question forcefully illustrates the need to distinguish between two perspectives one can take on fictional characters: either one looks at them from the inside by imagining what the story they originate from “invites us to imagine” [2] or one looks at them from the outside “qua fictional characters” [3]. A statement displaying an internal perspective is usually called a fictional statement, while one that displays an external perspective is usually called a metafictional statement1 [4,5,6]. Fictional statements are intuitively true in the fiction, while metafictional statements are intuitively true simpliciter. From Lamarque and Olsen’s striking example, one should thus clearly distinguish between the following:

- (1)

- Victor Frankenstein created Frankenstein’s monster. [True in the fiction]

- (2)

- Mary Shelley created Frankenstein’s monster. [True simpliciter]

The semantic contribution of fictional referring expressions like “Frankenstein’s monster” (FM henceforth) thus depends on the context of use: “FM” denotes Victor Frankenstein’s creation in fictional contexts, and denotes Mary Shelley’s creation in metafictional contexts. It will be useful for discussion to introduce labels for these distinct entities. I will thus call Victor Frankenstein’s creation the flesh-and-blood individual, and Mary Shelley’s creation the individual of paper. This terminology does not commit to any view about the nature and existence of these entities2 [3].

Interestingly, fictional statements about Victor Frankenstein’s creation are remarkably unproblematic. Indeed, Victor Frankenstein is a perfectly ordinary creator: he brings into existence his creature and later interacts with it in the way the fiction describes. He is the maker of a new concrete thing in his own world. By contrast, there is something puzzling about Mary Shelley’s creative process. Indeed, she did not create the same thing as Victor, but rather an abstract entity, which has grown to be very famous in our contemporary cultural landscape and has a place in the history of world literature. As such, Mary Shelley is not the maker of a new concrete thing in her own world, but the craftswoman of a literary thing (whatever that is).

This intuitive asymmetry has been called the “character problem” [7]. It is a general metaphysical problem, which can be put roughly as follows: how is it possible to create abstract objects? There is in fact a potential conflict between a naïve understanding of creation and the metaphysical distinction between concrete and abstract objects. Indeed, if abstract objects are causally distinct from concrete objects and/or if they are timeless entities (these are standard ways of characterising abstract objects), then it is not clear how a concrete individual like Mary Shelley, with concrete means, can make an abstract object like FM begin to exist. Part of the creationism debate over fictional characters thus overlaps with more general concerns about the interaction between the concrete/abstract distinction and the notion of creation. For the time being, the intuitive contrast between Victor and Mary shows that literary creation is arguably not a simple case of creation. In other words, Victor’s relation to FM is simpler to understand than Mary’s relation to FM, though both create FM in some sense to be explained.

More specific to the philosophy of fiction is the interpretation of “creationist locutions” [8] (p. 17), which leads to a debate about so-called “fictional creationism”: creationists argue that such locutions should be taken at face value; consequently, they hold that it is possible to create abstract objects in general and to create individuals of paper in particular, and they proceed to explain how [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]3. Anti-creationists deny this possibility and proceed to explain away creationist locutions. There are two well-known versions of anti-creationism: neo-meinongians hold that abstract objects in general cannot be created because they are timeless entities that are causally distinct from us [22,23], and fictionalists hold that individuals of paper in particular do not exist, and hence are not brought into existence in any sense [24,25]. I will argue for a new version of anti-creationism below.

Creationist locutions are essential in the philosophy of fiction for two different reasons. First, they are pervasive, idiomatic expressions: there are many ways of describing individuals of paper as outputs of a literary creation process. Here is a sample from the literature (my emphasis):

- (3)

- Some characters in novels are closely modelled on actual people, while others are wholly products of the literary imagination, and it is usually impossible to tell which characters fall into which of these categories via textual analysis alone [26] (p. 302).

- (4)

- When authors create fictional characters, they present them with more or less physical detail, but in the 19th century, there were authors who presented some of the characters they created with a greater wealth of physical detail than characters in any 18th-century novel [14] (p. 207).

- (5)

- Austen might have made her character Emma less attractive by giving her a worse temper [24] (p. 195).

- (6)

- Sherlock Holmes is a fictional character created by Conan Doyle. He first appeared in print in 1887, in A Study in Scarlet [3] (p. 26).

Statements (2)–(6) are all examples of creationist locutions which display an external perspective on the different fictions: they are metafictional statements which are true simpliciter. In fact, creationist locutions are paradigmatic examples of metafictional statements, and this is the second reason why they are essential in the philosophy of fiction. Metafictional statements have played a crucial role in the philosophy of fiction for half a century now; they are the linguistic data underlying the debate between realists and anti-realists about fictional characters. Realists hold that individuals of paper exist, while anti-realists deny this. Since seminal research by Kripke and Van Inwagen [27,28], it has been generally acknowledged that one can make an argument from the truth of metafictional talk to the conclusion that fictional characters exist in some sense4 [10,26,28,29,30,31]. In this context, creationist locutions are used as conclusive data against the intuitive anti-realist view.

Interestingly, some recent work in metaontology offers a new perspective on this realism/anti-realism debate (see, in particular the Yablo-Thomasson debate [32,33]), and from this new vantage point, one can see that creationist locutions in particular are paradoxical. Amie Thomasson and Stephen Yablo disagree about what counts as a good ontological argument, and have shed some light on what Thomasson calls “linking principles”, i.e., inferential patterns between existential claims and other specific claims. I will argue that these can be used to construct a paradox about individuals of paper. This paradox will contribute to a better understanding of what is at stake and provide a steady guide through the complex field known as the ontology of fiction5. In particular, I will use it to challenge the most attractive view in the field today, viz., artefactualism.

2. The Paradox

2.1. Terminology

Recently, Thomasson [34] defended a metaontological position she calls “easy ontology” [33,34,35,36]6. For her, an acceptable ontological argument is an argument which starts with an “uncontroversial truth” and ends with an ontological claim, via the use of one (or more) “linking principles”. Before commenting on the ingredients, here is a simple example of an acceptable ontological argument for mathematical realism from [37]:

- (i)

- There are two cups on the table.

- (ii)

- If there are n Ks, then the number of Ks is n.

- (iii)

- The number of cups on the table is two.

- (iv)

- There is a number.

(i) is an “uncontroversial truth” in that it is simply an intuitive, empirical claim (supposing that “there” is used in a context where there are indeed two cups on a nearby table). In general, an uncontroversial truth is a proposition that all parties can agree with independently of their ontological quibbling. (ii) is the “linking principle”: it is an inference pattern, which is basically a way of making one’s ontological commitments explicit. In general, linking principles should be analytical entailments, i.e., the disputants should accept (or reject) them by reflecting on the meaning of words only. Using modus ponens, (i) and (ii), we get (iii). And (iv) is an existential generalisation from (iii). Thomasson’s idea is that this is a valid realist argument; the correctness of the argument remains to be discussed, and mathematical anti-realists will typically deny one of the steps described here to block the conclusion.

It should be noted that Thomasson is famously very liberal on what counts as a linking principle, i.e., the idea that “analytical entailment” means “reflecting on the meaning of the words only” is very minimal. Consequently, she accepts realist arguments very easily. In doing so, she is not in line with the “standard” (i.e., neo-quinean) interpretation of ontological commitments, which consists in making explicit the “demands that the sentence’s truth imposes on the world” [38] (p. 428) or the “accurate measure of the ontological cost of a theory” [39] (p. 81). As will become explicit below, I argue against Thomasson while using her conceptual apparatus, and so I accept her very liberal definition in this paper. I will play Thomasson against Thomasson, as it were, and I hope to show that her conceptual frame is, for this reason, very useful in order to understand what is going on in the ontology of fiction.

2.2. The Paradox of Fictional Creatures

Here are three uncontroversial truths:

- (7)

- Mary Shelley created FM.

- (8)

- FM is a (purely) fictional character.

- (9)

- FM does not (really) exist.

Here are three linking principles, i.e., analytical entailment relations holding between these propositions7:

- (A)

- (7) ⇛ (8);

- (B)

- (8) ⇛ (9);

- (C)

- (7) ⇛ non-(9).

The contradiction should now be clear:

- Suppose (7) is true.

- Then, by (A) and (B), so is (9).

- Then, by (C), the negation of (9) is true.

- So, (9) is both true and false.

- Contradiction.

Let me first motivate the uncontroversial truths and the linking principles independently, and then I will consider the logical space of solutions.

2.3. Truths about Fictional Characters

The truth of (7) should be intuitive enough from the opening quote by [1]. To make the intuition very explicit, one can contrast (7) with the obviously false statement:

- (10)

- J.K. Rowling created FM.

It is important to keep in mind that (7) is intuitively true simpliciter, i.e., it describes the real world. In fact, (7)–(9) are to be interpreted as explicitly metafictional statements, displaying an unambiguous external perspective on fictional characters. As shown by examples (3)–(6), the intuitive truth of (7) is not an isolated phenomenon; creationist locutions are legion.

Statement (8) is also intuitively true. I have added “purely” in brackets here to enhance the contrast between “immigrants” and “native” fictional characters [22]; FM is not like Napoleon in War and Peace who is a paradigmatic case of a historical figure brought into fiction. The intuitive ground for this distinction is that characters are either purely fictional or historical, i.e., modelled on (or identical to) a real person. Many works of fiction, including Tolstoy’s novel, include both purely fictional characters, like Pierre Bezukhov, and historical figures, like Napoleon. There are disagreements about the status of historical characters in fiction, and about the semantics of real names in fiction8 [40]. It should now be clear that (8) is intuitively true for purely fictional fictional characters only, and so is the focus of the present paradox.

Statement (9) is a metafictional negative existential, i.e., a negative existential statement containing a fictional referring term in the subject position. Now, negative existential statements in general are known to yield conflicting intuitions and are a very old conundrum in Western philosophy. So, anything I will say about intuition in this context is bound to be met with criticism. However, there is a clear sense in which metafictional negative existentials are paradigmatic cases of true negative existentials, as opposed to false negative existentials like the following:

- (11)

- Stacie Friend does not (really) exist.

“Really” in brackets is supposed to elicit intuitions and help the sceptics9. Moreover, the contrast between (9) and (11) should be clearly pushing toward the idea that (9) is intuitively true (whereas (11) is intuitively false). Along the same lines, if you meet someone who thinks that FM exists (i.e., non-(9)) and dreads meeting it, then you would be perfectly justified to say something like (9) so as to reassure them. More importantly, if a reader of Frankenstein reads the story in such a way that they think that FM exists, then they have made an objective mistake. This much should be enough to intuitively justify (9).

As usual, with paradoxes, intuitions are misleading in some sense to be explained. So, calling (7)–(9) “uncontroversial truths”, borrowing Thomasson’s terminology, is something like a provocation; the fact that there is an open debate about creationist locutions is sufficient to show that these propositions are controversial. But it is an interesting provocation, I claim, because it invites one to look at the “linking principles” instead of rushing to analyse intuitions. This methodological delay, I think, is the take-home message of the recent Thomasson–Yablo debate in metaontology.

2.4. Linking Principles

Following Thomasson, linking principles should be thought of as analytic entailment relations between propositions. She thus means that a linking principle is something like a truth-preserving inference based on linguistic meaning only. In other words, (A)–(C) should intuitively count as linking principles iff one can accept the inference pattern reflecting on the meaning of the words only, i.e., without an empirical investigation. I now make these meaning intuitions explicit.

(A) is an instance of the following inference schema:

- Author X created Y.

- Therefore, Y is (purely) fictional.

Note that (A) is not as general as it may seem: it merely says that Y is fictional only if there is an author, X, who created it. Again, with the contrast between purely fictional and historical characters in the background, it should be intuitive enough. The difference between, say, Pierre Bezukhov and Napoleon in War and Peace, is that Pierre was created by Tolstoy and Napoleon was not. This inference is analytical; something is fictional so far as it is the output of an author’s activity, and this is partly what “fictional” means. Thomasson [33] (p. 5) has a very telling way of explaining this point10:

“Jane Austen wrote a book pretending to use the name ‘Emma’ to refer to a woman and describe various things she did (where Austen was not referring back to any real person or prior character)” and “Emma is a fictional character in a book by Jane Austen” are redundant: any competent speaker who knows the truth of the first is, according to the standard rules of use for our noun term “fictional character”, entitled to infer the second; nothing more, no further investigation, is required.

As for (B) it is an instance of the following inference schema:

- X is (purely) fictional.

- Therefore, X does not (really) exist.

One influential way of explaining this inference pattern is to say that (8) is a way of “characterising FM’s nonexistence”, using Kroon’s idiom [42]: in general, saying that X is fictional is just one way of saying that X does not exist11. The point is clearly articulated by Everett [24] (p. 131-2), commenting on Thomasson:

I would have thought that, in so far as there were any conceptual truths associated with our concept of a fictional character, or linguistic truths associated with the expression “fictional character”, these would surely include the fact that fictional characters do not exist […]. After all, ordinary people seem quite happy to move from the claim that x is a fictional character to the claim that x doesn’t exist. We talk and think as-if being a fictional character precludes that thing’s existence and indeed explains or entails its nonexistence. We naturally say such things as “Emma doesn’t exist but is only a fictional character”, “Sadly, since Holmes is a fictional character he doesn’t exist”, “You are in love with Anna Karenina, so you are in love with a mere fictional character, something that doesn’t exist”, “Fictional characters exist in stories, not the real world”, and so on. We would certainly find it bizarre if someone, upon being told that Holmes is a fictional character, asserted that Holmes exists.

Everett’s calling in the “ordinary people” talk is, I think, completely justified; for instance, see the following discussio n between three editors of the Wikipedia page “Sherlock Holmes”12:

- -

- So seeing as he came up with a lot of crime scene techniques isn’t he a bit of a genius? Or did he research new techniques before writing the book?

- -

- Do you mean Arthur Conan Doyle? Because Sherlock Holmes wasn’t a real person and he certainly didn’t write his own books! […] Raccooneyes55 21:17, 2 August 2011 (UTC)

- -

- Raccooneyes55, with all respect, the assertion that Holmes was a fiction is debatable; There are many good arguments made both for Holmes as a real person poorly hidden, and for Holmes as a fiction. His existence as a fictional character ONLY is far from provable. […] 96.54.72.207 02:24, 14 August 2011 (UTC)

Though the third editor disagrees with the second on Holmes’s existence, they clearly use the word “fiction” in a way that presupposes nonexistence. It is thus very reasonable to think that something like (B) is intuitively acceptable.

Turning to (C), it is an instance of the following inference schema:

- (Author) X created Y.

- Therefore, Y exists.

The basic idea in this inference schema is that part of the meaning of “to create” is something like “to bring into existence” or “to cause something new to exist”. I take it that it is intuitive indeed. For what it is worth, the first listed meanings of “to create” are “to bring into existence” (Merriam-Webster online) and “to make something happen or exist” (Oxford dictionary). This much attests that there is a strong linguistic connection between “creation” and “existence”. Conceptually, the link from creation to existence is also principled in some specific sense. Indeed, in theology, when it is said that “God created the heaven and the earth” (Genesis 1:1 King James Version), it clearly means that the heaven and the earth were thus brought into existence. Consequently, there is indeed at least one sense in which creation entails existence. And this is what makes (C) intuitive.

As will be clear from the discussion below, fictional creationists hold firm on the intuition behind (C). But the intuition is also shared among anti-creationists. Here is, for instance, Yagisawa [20] (p. 156-7) says that creation without existence makes a “mockery of the notion of creation”. Yagisawa adds the following:

It is an undeniable conceptual, indeed (I dare say) analytic, truth that for any x, if x is created, x comes to existence. To create something is to bring it into existence13.

(C) interestingly stands off in this context, because it abstracts away from fiction14. It is thus much more general than either (A) or (B), and suggests a general theory of creation in a way (A) and (B) do not. Being more general, it is also more fragile. As you might have guessed, this is where I think one can place a wedge and hammer a solution o the paradox. But I think it is useful to first examine the whole logical space of possible solutions.

3. The Logical Space of Solutions

3.1. Structural Remarks

We thus have put the problem in the form of a paradox. The problem is not new, as the debate over fictional creationism is fraught with long-standing contributions. I call it the paradox of fictional creatures because it unpacks the intuition that the expression “fictional creature” is something like an oxymoron: “fictional” pushes towards nonexistence, whereas “creature” pushes towards existence. The expression comes from the creationist locus classicus [26] and has been a successful expression since. I suggest that this is because it perfectly renders the controversial ontological status of fictional entities.

The interesting methodological point with paradoxes is that one can systematically classify existing and possible solutions. Thanks to this paradox, one can conceptually map the possible ontologies of fictional entities. After charting the existing ontological ground, I will offer a new solution to the paradox, which is a new form of anti-creationism, driven by a naïve theory of creation that I will argue for.

Before moving to the solutions, let me brush two non-starters aside. First, one could solve this paradox by embracing dialethism, and argue that our ontology of fictional entities delivers true contradictions. It is often argued that fictions breed contradictions [43,44]; hence, it is not astonishing that individuals of paper are good candidates for being contradictory, intentional objects [22,45]. That is surely one way to go, but I think it is fair to say that it does not explain what is specific about this paradox as opposed to other paradoxes. Indeed, embracing dialethism is a general strategy for solving paradoxes. Motivating the view would lead us afar from our subject, viz., fictional characters and the semantics of creationist locutions.

The second non-starter would be to deny that ⇛ is transitive. If transitivity fails, then one would go from (7) to (8) using (A) and from (8) to (9) using (B) without being able to go from (7) to (9), and thus block the above reasoning. But such a solution misfires in an interesting way. Indeed, there are independent reasons to accept (7) and (8) as true. Even if ⇛ was not transitive, we would still derive a contradiction using (B) and (C) alone. This is interesting, because it shows that (A) is somewhat irrelevant to the ontology of fictional characters. The conceptual work really focuses on the analysis of (7), (8), (B) and (C), with (9) being what is at stake.

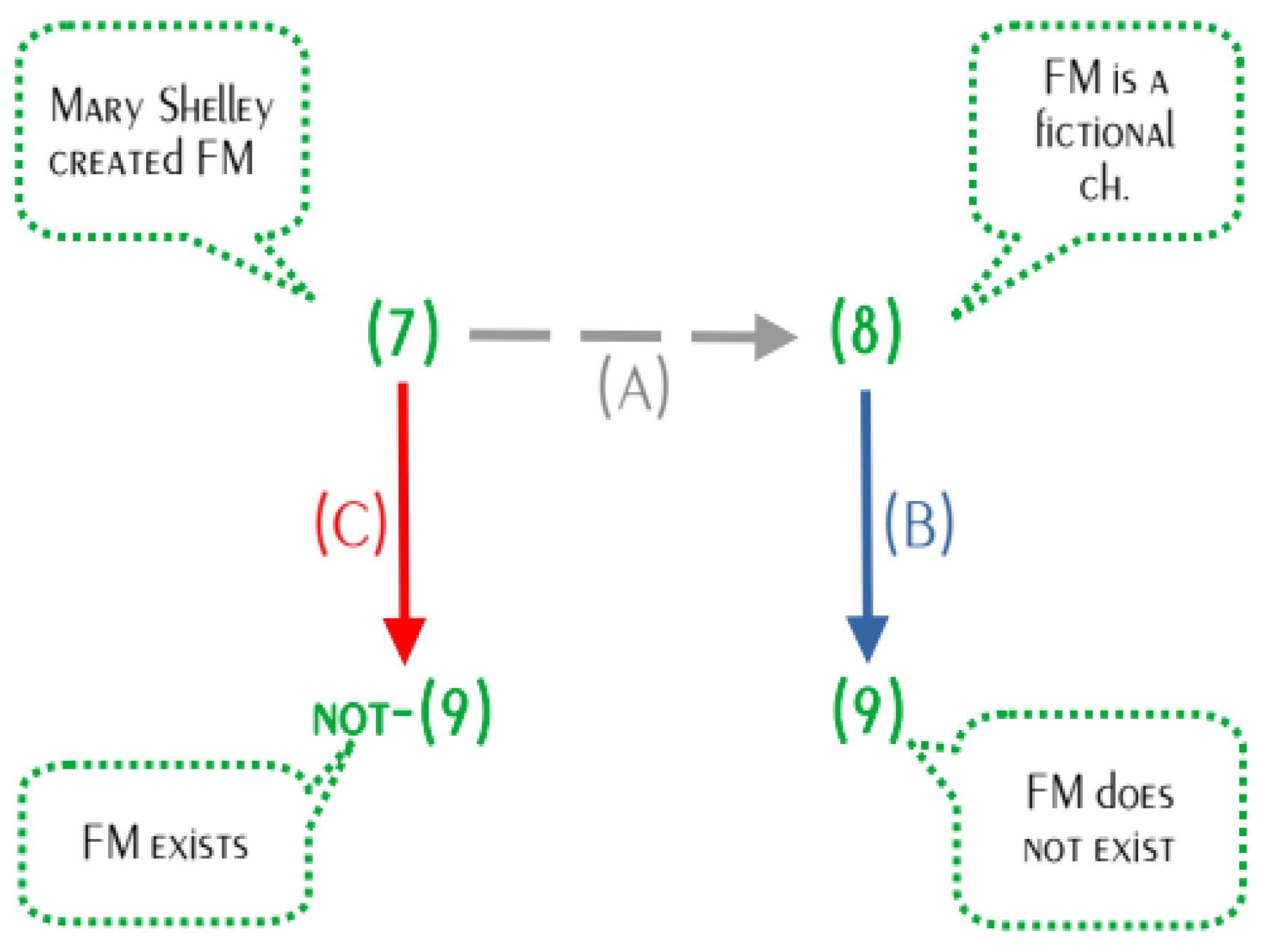

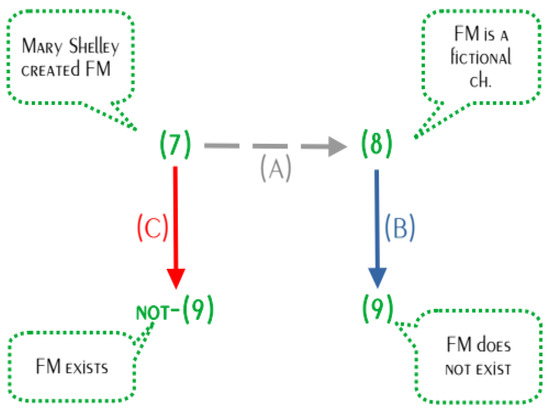

This last structural remark simplifies the logical space of solutions, which is represented in (Figure 1). It shows that removing either intuition that (7) is true or that (8) is true provides a solution. However, denying (9) is not sufficient. One must also reject (B); in other words, given (8), (B) is counter-intuitive with respect to (9). There is yet a last option, which consists in leaving the truths untouched, and challenging (C). This last solution is in fact minimal, in that it does not go against the intuitive truths and merely tweaks the ontological machinery.

Figure 1.

Structural version of the paradox.

There are thus four possible solutions15:

- α

- Deny (7): It is not the case that Mary Shelley created FM.

- β

- Deny (8): It is not the case that FM is a fictional character.

- γ

- Deny (9) and (B): FM really exists, and “being fictional” is not a way of “characterising nonexistence”.

- δ

- Deny (C): To create does not mean to bring into existence.

3.2. Inveterate Anti-Realism

“Inveterate antirealists” [18] have a drastic solution, which consists in denying that any metafictional statement is true simpliciter. Statements (2)–(9) all seem true about the real world, but they argue, metafictional statements are in fact sophisticated fictional statements which essentially involve pretence; hence, they are neither true nor false simpliciter16 [14,25,46]. In order to explain how pretence extends to metafictional contexts despite appearances, Walton [25] (p. 405-11) introduces the notion of a “non-official game of make-believe”. The notion of an “extended pretence” in [24] is similarly used, and Everett makes completely explicit what the underlying pretence of (7) and (8) amounts to. In [24] (§3.3.3), Everett gives truth-in-the-extended-pretence conditions for creationist locutions. Such locutions “can be understood as a straightforward extension EP of the original pretence P. We imagine the original world of pretence P but we will also pretend that real individuals have created or made up some of the things we imagine”. As for statements like (8), the same tool is used [24] (p. 66):

We will engage in an extended pretense in which we pretend that our domain of discourse contains all those entities which occur within some fiction and that those entities are as they are characterized by that fiction. So if some fiction involves our pretending that there is some entity i or plurality of entities p, the extended pretense will also involve our pretending that there is the entity i or the plurality of entities p. And if some fiction characterizes x as being F then x will count as being F within this extended pretense. Within this extended pretense, those entities which genuinely exist will count as having the property of being real and those which do not will count as having the property of being fictional17 [47].

There are two main objections to this inveterate anti-realism. First, in the present context, the departure from intuition sounds unjustified; one can see that such use of extended pretence is too strong, since it leads to the rejection of both (1) and (2). Inveterate anti-realists thus go for both (α) and (β). One might look for a minimal solution to the paradox of creation instead.

Second, there are more general worries about this idea of extending the original pretence. As I show in [30] (§1.2.2), metafictional negative existentials put a lot of pressure on the inveterate anti-realist. Indeed, anti-realists have to say that metafictional negative existentials like (9) are not, strictly speaking, true, because they are true in an extended pretence. Truth simpliciter is distinct from truth in some pretence, by definition. Using extended pretence carelessly thus pushes anti-realists on the verge of inconsistency; they hold, in general, that fictional characters do not exist (i.e., the anti-realist tenet), and in particular, they hold that “Emma Woodhouse does not exist” is not true simpliciter, but is true in some extended pretence. It now dangerously sounds like theoretical schizophrenia.

Another way of putting it is that since the inveterate anti-realist thinks that (7) and (8) are true in some extended pretence, one can then run a version of the paradox within their preferred extended pretences. There, they will not be able to escape it in the same way, and they will have to take a stance on whether or not the linking principles apply in their extended pretence. They thus do not solve the paradox, but merely displace it.

3.3. Neo-Meinongianism

One can interpret solution (α) as taking the above paradoxical argument as a reductio: let us suppose that Mary Shelley created FM, but this contradicts the fact that FM does not exist, so it cannot be that Mary Shelley created FM. According to this line of reasoning, (A), (B) and (C) are all good inference patterns, and they thus provide us with good reasons to deny (7). One should then explain why (7) seems true, but is in fact not true.

To this end, neo-meinongians have developed the idea that fictional characters are not created, but rather discovered. In [22] (p. 188), Parsons makes this neo-meinongian tenet crystal clear:

I have said that, in a popular sense, an author creates characters, but this […] is hard to analyse. It does not mean, for example, that the author brings those characters into existence, for they do not exist. Nor does he or she makes them objects, for they were objects before they appeared in stories.

Using a different terminology, Zalta [48] argues that they are “roles” which exist independently of authors, and authors “choose” them. More recently, Priest [23] (p. 114) argues that fictional characters like FM are nonexistent concrete individuals, and that authors “mentally point” to them:

[W]hen Doyle coined the name “Holmes” he gave it to a non-existent object, picked out as an object which was a detective with acute powers of observation and inference, etc., in the worlds that realised the story he wished to tell. This was achieved with an act of mental pointing; and, realistically conceived, the object was available to be pointed at. But how does the pointing work? How does the act pick out one of the enormous number of non-existent objects? In many worlds there are objects—different objects—which are detectives with acute powers of observation and inference, etc. How does the act pick out one of these? […] I do not, myself, find a problem with a notion of mental pointing that can do this, any more than I find a problem with a notion of physical pointing that selects an object at random. (Close your eyes and point to someone in a crowd.)

Contrary to Priest, most philosophers of fiction “find a problem” with the idea that authors “mentally point” to fictional characters: it has been conceived as the “selection problem” by Sainsbury [49] (p. 61-3; 82-5), or as the “espistemological problem” by Zvolensky [21]. Against the neo-meinongian strategy, intuition re-asserts itself again and again when one considers the multifarious creationist locutions. It is thus hard to swallow that fictional characters are somehow ontologically independent from whatever the author does, and so looking at the paradoxical argument as a sound reductio against (7) sounds like an ad hoc trick to avoid the real problem, viz., the underlying theory of literary creation, which is needed all the same.

Another way of putting the objection consists in strictly distinguishing fictional entities from other nonexistent intentional entities, e.g., the golden mountain, the present king of France or the round square. Fictional entities have a special relationship with their author(s) and consumer(s): one cannot conjure up a fictional character at will, pace Priest. The crucial idea is that fictional characters are introduced into a community; people have to imagine them, and in this specific sense, they are in fact dependent on human activity. By contrast, mere (im)possibilia do not depend on an author or a community of imaginers to be available (or to subsist). Neo-meinongians deliberately conflate the two kinds of nonexistent intentional entities, and this is what is wrong with their solution18 [50].

3.4. Artefactualists and Anti-Creationists

Contrary to neo-meinongianism, artefactualists take the content of creationist locutions very seriously and at face value. The author does more than simply drive the reader’s attention to a particular spot in the intentional space; rather, they craft a character. Here is the artefactualist tenet: “ficta depend for their existence on the ultimately imaginative activities of certain people—basically, make-believe practices of certain sorts, primarily storytelling practices—which make them abstract entities of a certain kind, mind-dependent abstracta” [10] (p. 279). Fictional characters are thus construed as abstract cultural artefacts alongside other such objects like constitutions, symphonies, borders and the like. Solution (γ) singles out artefactualism in our logical space.

The forerunners of this view are Kripke [27], Searle [51] and Van Inwagen [26]. A new generation including Schiffer [41], Salmon [52] and Thomasson [9] made artefactualism popular; it then became the “œcumenical view” according to Recanati [3], along with a new generation of artefactualists including Terrone [53], Walters [54], Abell [11] and Voltolini [10]. It is now widely acknowledged that the artefactualist view provides a simple and powerful ontology, which is required to give adequate semantics of metafictional statements in general.

One interesting remark is that artefactualism is more revisionary than the other solutions (indeed, it aims at rejecting both a truth and a linking principle). This is why artefactualism leads to several meta-ontological debates, as Thomasson saw very clearly. In particular, artefactualists have to make room for abstract artefacts, i.e., abstract entities which have a function and a life span: they are created and used, and they can disappear. Artefactualists thus rely on slightly non-standard metaphysics, which was forcefully put forward in [9]. Anti-creationist solutions to the paradox thus have a prima facie advantage in that they do not rely on a general metaphysical picture to be argued for. That being said, arguing for a standard approach to metaphysics falls outside the scope of this paper, so I think that this first remark is not decisive.

As for the philosophy of fiction proper, the artefactualist argumentative strategy consists in holding firm that (7) + (C) entails that FM exists, contrary to appearances. Thomasson’s [29] strategy is to say that this bullet is not too difficult to bite, given that negative existentials in general are controversial and perhaps the most robust philosophical conundrum in the Western tradition. As a result, going against a controversial intuition is not that bad. Moreover, since everyone in the debate is part of this Western tradition, the semantics of negative existentials can be thought of as an orthogonal problem, which affects all views. Later on, moving from an intuition-based strategy to metaontology, Thomasson [33] rightly shows that the argument for artefactualism should rather be a defence of linking principle (B) over (C). Indeed, so long as both principles are implicitly accepted, our conflicting intuitions about metafictional negative existentials like (9) will constantly re-appear. Artefactualists should thus motivate the value of (C) over that of (B); the inference from creation to existence is, so they argue, a better inference than that from fiction to nonexistence.

Solution (δ) relies on the opposite strategy according to which (B) is preferable to (C). They are the remaining anti-creationists. Their argumentative task is, prima facie, a lot easier: they do not have to explain away any intuition. They must only reject linking principle (C): we do not infer existence from creation. In other words, it suffices to display counter-examples to (C). For instance, Kroon argues in [14] that we use “to create” when we talk about children’s imaginary companions without ever implying that these exist in any sense. Along the same lines, Deutsch’s [7] (p. 210), the rejection of (C) is based on the following counter-example:

It is surely possible, for example, for two composers independently and at different times to create exactly the same melody. If creating a melody entails bringing it into existence, we are hard pressed to explain how the composer composing at the later time could have created anything. The statement that X is caused to exist at t entails that, during some interval immediately prior to t, X does not exist. If t is the time at which the later composer creates the melody, we have no reason to suppose that such an interval exists.

In this case, we are tempted to say that composer X created melody Y, but Y’s existence does not depend on X’s creative act, for it existed before. “To create”, if properly used here, does not always imply existence. The next step is the following: the debate on whether “to create” entails existence is an empirical matter, and so (C) is not a linking principle according to Thomasson’s own standards.

But artefactualists and anti-creationists talk past each other in this metaontological discussion because (C) is, in fact, ambiguous between a descriptive and a normative reading. Artefactualists typically say that (C) is a normative principle, i.e., people should infer existence from truthful creationist locutions like (7). Exhibiting counter-examples to (C), however, consists in showing that (C) is descriptively false, i.e., it happens that people do not systematically infer existence from creationist locutions (non-(9) from (7)). But these claims are compatible; people should infer existence from creation, but they do not. There are so many things people should infer that they do not!

What this discussion shows is that there is a stronger version of anti-creationism, which consists in arguing that (C) is not only descriptively false, but it is also normatively bad19 [7,14]. This solution requires a theory of creation, i.e., what “to create” should mean. I will provide that now, and it will appear that this new solution be an interesting mix of solutions (α) and (δ).

4. Bringing a New Solution into Existence

4.1. An Analysis of Creation

Creation, I claim, should be analysed into two more basic notions; to put it bluntly, to create means to both invent and realise, i.e., to create means doing two things, viz., to invent and to realise20. A creator, in the proper sense, is someone who (usually, but not necessarily) designs what they want to produce first, and then sets up to make a thing which (usually, but not necessarily) corresponds to the design. Consequently, when the two stages of creation are radically distinct, it is difficult to tell who the creator is.

Here is some linguistic evidence: let us define “helicopter” as a specific type of aircraft which can hover, take off and land vertically. Now, the following two statements are both infelicitous:

- (12)

- [?] Leonardo da Vinci created the helicopter, i.e., the “aerial screw”, in the 1480s.

- (13)

- [?] Juan de la Cierva created the helicopter, i.e., the “autogyro”, in the 1920s.

Leonardo’s aerial screw is a helicopter in our sense; some technical drawings were produced, it flies “on paper”, but at the time, there was no sufficient power force to make it fly. Leonardo did not create the helicopter in the strict sense, for he merely invented it. As for Juan de la Cierva, he built autogiro C.4, which is the first flying helicopter in our sense, though he did not invent it: Juan de la Cierva did not create the helicopter in the strict sense either, for he merely realised it. This example is based on a case where the design and manufacturing processes are radically distinct. In such cases, it is difficult to say who creates what.

Moreover, there are good reasons to hold that creation cannot be reduced to invention; realisation is a necessary component of creation. Suppose that creation was wholly on the side of invention. Then, the opening of Genesis 1:1, “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth”, could be true had God simply made a technical drawing of the real world à la Leonardo. But it is clear that the situation described in the Bible of an almighty God who created the world by fiat is different from a scenario in which a God thought up a world without realising it21 [55]. It appears that God’s realising the world is a necessary condition for God’s creating it.

Perhaps creation can be reduced to realisation without invention, though my feeling is that this is a slightly deviant use of the term. Take, for instance, Plato’s demiurge: it is explicit from Timeus (51a) that the demiurge realised the world without inventing it. Indeed, the Demiurge stares at the pre-existing Platonic Forms while informing Khôra. If we are tempted to say that Plato’s demiurge is a creator, then creation is more on the side of realisation than invention. On the other hand (and this is where my intuition goes), one might want to deny that Plato’s demiurge is a creator on the basis that it does not invent. The same sorts of intuitions should apply to the idea that natural processes (be it the vital force, Natura Naturans, evolution or what not) are creative, as opposed to merely productive.

I have two remarks. First, this naïve analysis explains the contrast between (1) and (2), which gives rise to the “character problem”. Indeed, Victor Frankenstein is a full-fledged creator in the story; he invented and realised FM. By contrast, Mary Shelley did not realise FM when she wrote and published her book (more on this below); this is, I argue, the crucial difference. Second, the initial quote by Lamarque and Olsen shows that one can pragmatically identify “to create” and “to invent” in context. However, according to the present analysis, Lamarque and Olsen’s quote has a zeugmatic flavour22.

4.2. Last Word with the Artefactualist

This naïve analysis of creation is perhaps much too naïve to achieve anything. Maybe it works for God, who is supposed to have created the real world, but authors create fictional worlds23. The artefactualist has another theory for literary creation in mind, which is arguably better.

Granted that Mary Shelley is closer to Leonardo than to Juan de la Cierva (she invented FM but she did not realise it)24 [24,25], some artefactualists are ready to deny the ontological significance of this distinction on the ground that invention is already something; inventors produce in some sense, and the inventor’s output is precisely what is meant to be captured by the idiom “abstract artefact”. In other words, they argue that individuals of paper are invented, and that is what creationist locutions say.

More precisely, Mary Shelley produces something in the real world without any doubt, viz., a fictional text which serves as a basis for the reproduction of the readable copies of Frankenstein. Such artefact is not yet FM, but it grounds the typical practice of a shared imagining of FM (among many other things). Such a shared practice is “a necessary, but not sufficient condition for a fictum to come into existence. What is further required is that a certain reflexive stance on that make-believe practice takes place”. This is what Voltolini [10] (p. 279) calls “moderate creationism”. The most accomplished theory of this “reflexive stance” is Abell’s institutional account of fiction that is forcefully advocated in [11]; a fiction institution is a solution to the coordination problem that authors face when they try to successfully communicate imaginings. Referential expressions, when governed by the rules of fiction institutions, generate fictional entities. Fictional characters are thus created social entities, given this relevant institutional mechanism. Terrone [53] also has a version of artefactualism, according to which fictional characters are inventions of a specific abstract kind, viz., types, whose main functions are to prompt token imaginings in the reader’s mind. In this model, the fictional character is realised when the (real) type/(imagined) token structure (a double mental file in Terrone’s framework) is deployed in a community of readers. Some inventions exist, so the artefactualist concludes25 [10,56].

I agree that inventions are already something, but I deny that their claim to existence is strong enough to run the creationist argument. At this point, the metaontological considerations are important. Indeed, all artefactualists count on the fact that (C) is a stronger principle than (B). In the “moderate” version, we are entitled to infer existence from invention on the condition that the kind of invention at issue follows specific constraints (Voltolini’s reflexive stance, Abell’s fiction institution, Terrone’s double file-ness, etc.) But (B) says that what is fictional is nonexistent, and I contend that it trumps (C) when it comes to inventions. In other words, there is a difference between Leonardo’s aerial screw and FM: both are inventions, but one is fictional and not the other. Maybe they are both something to consider for existence on the ground that they are both inventions, but given (B), we have good reasons to hold that the fictional one does not exist. Inventions, in general, can exist or not depending on whether and how they are realised, and this is an empirical matter. Counting some complex structure involving imagination as proper realisation sounds like a weak vindication of (C) when compared to the force of (B)26 [57].

Let me emphasise this last point and rehearse the anti-creationsist argument against an influential version of artefactualism, viz., the theory according to which fictional characters are (created) types (see, in particular Lamarque [58], Terrone [53] and Walters [54,59]). Relying on the traditional type/token distinction, this brand of artefactualism argues that the entailment from fiction to nonexistence (i.e., (B)) holds at the level of tokens but not at the level of types, and it thus suffices to distinguish between the token character (the flesh-and-blood individual, in my vocabulary), which does not exist and is not created at all, and the type character (the individual of paper in my vocabulary), which is created and existent. In general, they add, types are ontologically innocuous enough and we have good reasons to include them in our ontology anyway27 [59]. It follows that if individuals of papers (i.e., an author’s creations) are types, they have a claim to existence after all. The artefactualist move consists in holding that types dwell outside the scope of principle (B), if (B) is a principle. As a consequence, they say, (B) is not in competition with (C) at the level of types. Mary Shelley thus created a type (not a token), and this is a vindication of artefactualism.

The claim that (B) does not apply to types is false, for the real/fictional distinction applies to types as well as tokens. (In my vocabulary: some inventions exist, and some others do not). To see this, let us focus on an uncontroversial example of a type, viz., a language. A language is a type whose sentences are tokens. There are real and fictional languages: English is a real language (this sentence being a token of the type); Tengwar is a fictional language (a fictional token sentence of such language is inscribed on the One Ring in Tolkien’s famous fantasy). One can thus wonder, for a given language, whether it is fictional or not, e.g., in order to ascertain whether that language exists or not28 [42]. Hence, at the level of types, too, (B) can trump (C), as one might reasonably infer from the fact that Tengwar is fictional to the nonexistence of such language, though it is undoubtedly Tolkien’s invention. Appealing to types (or inventions) thus begs the question, since the competition between (B) and (C) appears both at the levels of types and tokens, contrary to what type theorists presuppose. Fictional characters qua abstract artefact, whether they are conceived as types or not, do not exist according to my argument based on the precedence of (B) over (C). Individuals of paper are invented, but not created.

5. Conclusions: Solving the Paradox

My defence of anti-creationism thus consists in restricting (C) as a good linking principle for full-fledged creations only; when creator(s) both invent and realise, then they have brought something new into existence. We know this analytically, without any further empirical investigation. But it does not extend to mere inventions. When it comes to inventions, new things are sometimes brought into existence, and sometimes they are not. The important point is that the inference from mere invention to existence, if any, is not analytical and it needs further empirical investigation. Even if one is a moderate creationist, one will agree that for a character to exist, there must be uptake, and this is contingent. Hence, there is no linking principle that is analogous to (C) to be found in the vicinity. (B), however, is untouched.

When applying this to individuals of paper, it follows that (7) appears to be ambiguous between the following:

(7a) Mary Shelley invented Frankenstein’s monster.

(7b) Mary Shelley invented and realised Frankenstein’s monster.

(C), I contend, is valid when it goes from (7b) to non-(9), but invalid if it goes from (7a) to non-(9). Now, (7b) is clearly false, and since (7) is intuitively true, it should be disambiguated as (7a). The paradox is solved, since one cannot combine (C) with (7a) to run the paradoxical argument.

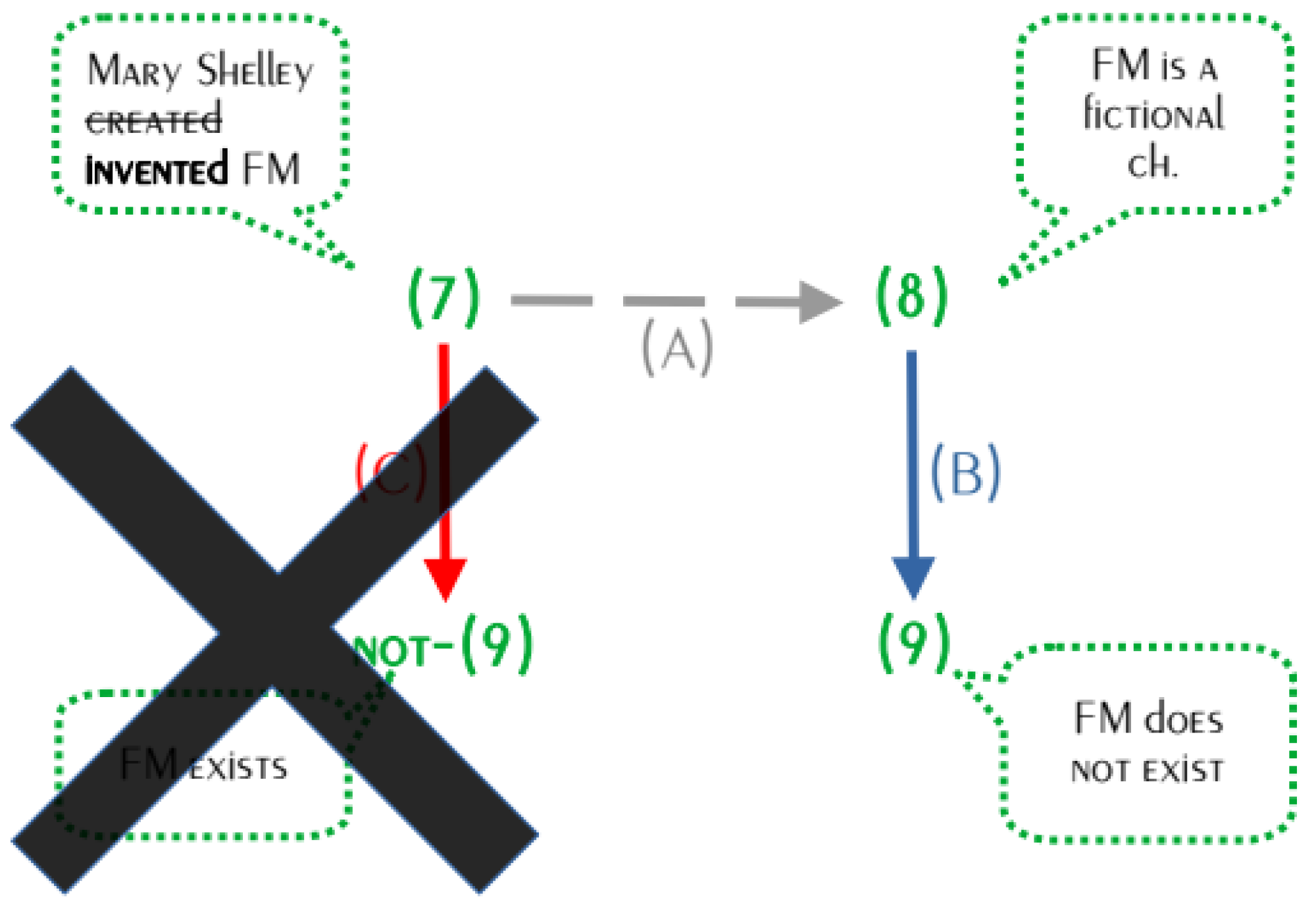

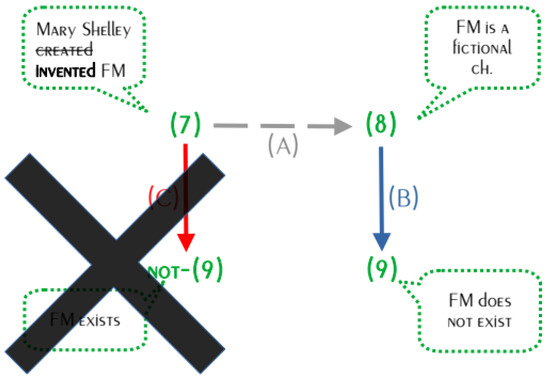

I think this solution can be seen as a middle ground between solutions (α) and (δ). It can be seen as claiming that (7) is not, strictly speaking, true because it is ambiguous (viz., (α)). But, given a charitable reading of (7) as (7a), it is indeed true. However, in this case, (C) does not apply. This restriction of (C) can be seen as a normative variant of (δ). For those of us who like schemas, here is what I have done to the logical space (Figure 2):

Figure 2.

My solution to the paradox.

I want to end with a small remark on the defence of my deliberately naïve theory of creation, which is meant to deprive literary authors of the title of full-fledged creators. Instead of taking God as the ideal creator for theorizing, one can think of architecture as the paradigmatic creative art. In architecture, the design process and the realisation process are very clearly distinguished, and the interaction between the two processes is as complex as can be. By contrast, literature is not a paradigmatic case of creative art, for it typically lacks the realisation process. It will not come as a surprise to think of architecture as fundamental for a theory of creation, especially for those who are familiar with Hegel’s seminal classification of the arts. By no means did I wish to suggest that Hegel was naïve, though.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This paper grew out of an intense period of writing postdoc applications at the Collège de France, thanks to François Recanati who provided me with the first step into the endless staircase Academia appears to be. These ideas were first shared and discussed on 9 September 2022 at the British Society of Aesthetics annual conference; on 3 October 2022 at Sorbonne Université in the “Second Fictionalism Workshop” organised by Michèle Friend and Fabrice Pataut; and on 11 January 2023 at Ruhr Universität Bochum in Kristina Liefke and Dolf Rami’s bi-weekly colloquium “Philosophy of Language, Logic, and Information”; I want to acknowledge the quality and usefullness of these exchanges, and collectively thank all participants and organisers in these events. This paper benefited a lot from several discussions with Enrico Terrone, especially when I visited him at the University of Genova in Spring 2023. Alberto Voltolini and Frederic Kroon deserve special thanks for their support, their interest, and their very detailed comments on previous versions of the manuscript. Thanks also to Hannah Kim for her careful reading and for comments on an earlier draft. Last, but not least: thanks to three anonymous reviewers for their uncompromising criticisms.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | There are alternative terminologies corresponding to the same distinction. For instance, Gregory Currie distinguishes between “fictive” and “transfictive” statements [4]; Andrea Bonomi distinguishes between “textual” and “metatextual” statements [5]. This distinction between fictional and metafictional statements is not taken to be exhaustive, as all authors usually single out parafictional (or paratuxtual) statements, as well as many other mixed-perspective statements. I ignore these more fined-grained distinctions for they do not affect the rest of this paper. For a recent overview of the different problems surrounding the different uses of fictional names, see [6]. |

| 2 | However, as will be seen below, the problem I want to investigate helps to distinguish between competing theories on the existence and nature of individuals of paper, viz., neo-meinongianism and artefactualism on the realist side, and fictionalism and anti-creationsim on the anti-realist side. “Flesh-and-blood individuals” comes from [3]. “Individuals of paper” is a tribute to Salvador Plascencia’s 2005 metafiction entitled The People of Paper. |

| 3 | See [9] for a very influential defence of creationism in general, later called “artefactualism”. See [10] for a useful distinction between “radical creationism” and “moderate creationism” (and an argument in favour of the latter): more on this below. See [11] for a recent book-length defence of creationism based on an institutional theory of fiction. The debate over fictional creationism has grown to be considerably large by now; some influential, fairly recent contributions include [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. |

| 4 | The force of the argument is comparable to the force of indispensability arguments in the philosophy of mathematics, taking the “best scientific practice” regarding fictional characters to be literary studies [28,29]. For recent discussions about the correctness of such arguments, see [10,30,31]. |

| 5 | This re-framing of the creationism debate involves a focus on fictional names and avoids quantificational talk. Creationism is sometimes advertised using talk such as “There are fictional characters and these are created entities”. I think we can narrow down the problem on existence and reference, leaving quantification aside, without trouble, though. Additionally, the theory of quantification over nonexistents brings forth orthogonal technical questions. In the same vein, nothing I argue in this paper hinges on fine-grained distinctions about fictional terms, viz., between fictional names and fictional definite descriptions. I will thus also leave this distinction on the side. |

| 6 | For the record, she considers her view to depart from mainstream meta-ontology derived from the classic [35] and to be in line with the seminal [36]. For a critical discussion of her view against this background, see [33]. |

| 7 | The arrow suggests itself for symbolising an entailment relation. I take this triple arrow so as to not prejudice any notion of entailment and go along with Thomasson on whatever suits best. In other words, nothing hinges on this notation. |

| 8 | For a seminal paper on this problem, see [40]. |

| 9 | “Really” should not be interpreted as “physically”, because realists typically hold that fictional characters really exist, i.e., exist in the real world, while being abstract. I am following the usage from the literature that “to exist” can be used for both concrete and abstract entities and means something like “being part of the real world” across the board. Thanks to Hannah Kim for pressing me on this point. |

| 10 | For the record, she is rephrasing and agreeing with Schiffer [41] here, who is another important creationist figure. |

| 11 | Note that this is not the only way of “characterising nonexistence”. Kroon considers many other cases, including the much commented upon example of an “imaginary friend”; saying of an entity that it is an imaginary friend is to contrast it with real friends by emphasising its nonexistence. The fact that “fictional” is a nonexistence entailing predicates (among others) has been explicitly held in many places. In [20] (p. 169), (B) is taken to be a “devastatingly simple” objection to creationism, and it is explicitly endorsed: “Unlike you and me, Mrs Gamp is a fictional individual. To say this entails that Mrs. Gamp does not exist. Fictionality of a thing entails its non-existence”. He then addresses the “two standard creationist replies” based on paraphrase. Artefactualists have since come up with other more elaborate replies; I argue against them in the last section. My position can thus be seen as an update on Yagisawa’s final argument. |

| 12 | The discussion is archived here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Talk:Sherlock_Holmes/Archive_2#Genius accessed on 11 September 2023. |

| 13 | His emphasis. Later on, he writes the following: “We should be careful enough to distinguish creativity from creation. The creativity with which an author describes a fictional character need not consist in her bringing the character into existence. It may instead consists in an unusually imaginative manner in which she writes a story”. My defence of the naïve analysis of creation below can be seen as going in this suggested direction. |

| 14 | This is why I put (Author) in brackets, for (C) relies on intuitions about a general theory of creation. I am following usage here in not making a difference between authorial and non-authorial creation. As the opening quote shows (and other “creationist locutions”), literary authors are typically thought of as being full-fledged creators. My solution below will consist in challenging this, and downgrade authors to mere inventors, so to say. Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for pushing me to clarify this. |

| 15 | These can obviously be combined, but that would be redundant. |

| 16 | This view was championed in [25,46]. See also [14] for a review and assessment of this traditional fictionalism. |

| 17 | Along the same lines in [47] (p. 9), Brock argues that, despite appearances, (8)’s logical form is something like the following: “According to the realist’s hypothesis, FM is a fictional character.” |

| 18 | Granted that fictional characters not only enjoy a special relationship with their authors (the creative relationship), but also with the consumers of the fiction who imagine them, it has to be acknowledged that the interactions between authors and their reading community is very complex. The author does not enjoy unbound authority; there is an uptake mechanism at play for fictional characters, contrary to mere (im)possibilia. The disanalogy thus re-appears on the consumer’s side; fan-fictions are always possible, whereas there is no fan-(im)possibilia. Though perhaps the literature on neo-meinongianism could be seen as a philosophical fan-fiction based on the Gegenstandstheorie! (For a similar joke, see [50]—which contains mostly serious contributions apart from the title.) |

| 19 | There are hints towards this view in [7,12], but, to my knowledge, the view has never been fully developed. |

| 20 | There are alternative terminologies: “to invent” can be thought of as synonymous with “to plan”, “to thought up”, “to make up” and “to imagine”, while “to realise” can be thought of as synonymous with “to make it the case that”, “to bring into existence” and “to produce”. |

| 21 | Arguably, the Australian aboriginal notion of “Dreamtime”, according to which, roughly, the world we live in is that of a God’s dream, is a myth of the origin based on mere invention, and not full-fledged creation. Interestingly, there is a debate in anthropology about the correct translation of the original term “alcheringa”, which is due to the interpretation of the distinction between linear and cyclic time that is crucial to the aboriginal culture, and which has consequences for what creation amounts to. Swain [55] thus proposes the word “uncreated” as a candidate: ‘Dreamtime’ or ‘Dreaming’, as T.G.H. Strehlow has noted, emerged with a mistranslation of the altjira root, which has the meaning of ‘eternal, uncreated, springing out of itself’. Altjira rama, literally ‘to see the eternal’, is the evocative description for human sleep-dreams, but the so-called ‘Dreaming’ is derived from Altjiringa ngambakala: ‘that which derives from altjira’. Strehlow grasps at ‘having originated out of its own eternity’ as the closest possible English equivalent. |

| 22 | So, I predict that the opening example is really a piece of (great) rhetoric, and not decisive linguistic data. Moreover, Lamarque and Olsen’s zeugma, which is based on the proximity of the English words “to create” and “to invent”, does not translate so well. Italian, French and German speakers concur in saying that it sounds odd to use a literal translation of “to create” to describe the special relationship that is held between an author and a fictional character, though it is completely idiomatic in English. |

| 23 | The analogy between God and the author is a commonplace in the literature from the 19th century. See, in particular, Flaubert’s famous letter to Louise Colet, where he wrote the following in 1852: “in his work, the artist must be like God in the universe: everywhere present but nowhere to be seen.” |

| 24 | Remember, what Mary Shelley is supposed to have created is distinct and different from the human-like monster that Victor Frankenstein has created. She is supposed to have created an abstract artefact (or a type, for the type theorist), which has a place in the history of the literature, and is indeed akin to Leonardo’s invention. A proper analysis of the difference between Leonardo’s and Shelley’s creative processes would require a full-fledged analysis of fiction making, which greatly exceeds the scope of this paper. For the record, and in line with the anti-realist line of my argument, I think the promising starting point is an analysis of make-believe as presented in [25] and developed as Everett’s [24] “pretence semantics”. Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for pressing me to make this more explicit. |

| 25 | I concur with Voltolini’s [10] (p. 292) terminological remark that “artefact” is not a good word for this new version of creationism championed by Abell, Terrone and Voltolini, because the analogy with manufactured goods is utterly misleading. I stick to the label for historical reasons, and for lack of a better term, provided this present caveat. For a misleading analogy between inventing a fictional character and carpentry, see [56]. |

| 26 | I think the same point is put forward in [57] (p. 364), when disagreeing with Thomasson’s defence of principle (C) as expressing an analytic truth. I am unsure whether Connolly would go for (B) over (C); he explicitly asserts that his account is anti-realist (denying the existence of fictional characters), while at the same time, in several places, talks about the existence of “characterisations”. Depending on whether he identifies “characterisations” with types, my argument would apply against his view. |

| 27 | Especially if we focus on (repeatable) works of art like novels, plays, pieces of music, etc. See [59] for an apt and influential defence of this view. |

| 28 | Note that, in line with Kroon [42] as noted above, there are other ways of being nonexistent for a language (and other types). Note that languages can fail to exist for non-fictional reasons. For instance, take a language in which the rules for negation are linear (e.g., to negate a sentence, place the negation word in the second position of the linear order). It is an empirical fact that there is no such language. Moreover, syntacticians have argued for the stronger claim that on the basis of the hierarchical structure of all languages, such a language could not exist. Such a language was “invented” by linguists, or rather stipulated in the course of a reductio argument, which is another typical way of “characterising nonexistence”. |

References

- Lamarque, P.; Stein, H.O. Truth, Fiction, and Literature: A Philosophical Perspective; Clarendon Library of Logic and Philosophy; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Friend, S. The real foundation of fictional worlds. Australas. J. Philos. 2017, 95, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recanati, F. II—Fictional, Metafictional, Parafictional. In Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; Volume 118, pp. 25–54. [Google Scholar]

- Currie, G. The Nature of Fiction; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi, A. Fictional context. In Perspectives on Context; CSLI Publications: Stanford, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 213–248. [Google Scholar]

- García-Carpintero, M. ‘Truth in Fiction’ Reprised. Br. J. Aesthet. 2022, 62, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, H. The creation problem. Topoi 1991, 10, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lihoreau, F. (Ed.) Truth in Fiction; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Thomasson, A.L. Fiction and Metaphysics; Cambridge Studies in Philosophy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Voltolini, A. How to Vindicate (Fictional) Creationism. In Abstract Objects: For and Against; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 277–294. [Google Scholar]

- Abell, C. Fiction: A Philosophical Analysis; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, S. A Recalcitrant Problem for Abstract Creationism. J. Aesthet. Art Crit. 2018, 76, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, J. Creatures of fiction, objects of myth. Analysis 2014, 74, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroon, F. The fiction of creationism. In Truth in Fiction; Franck, L., Ed.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 203–222. [Google Scholar]

- Kroon, F. The social character of fictional entities. In From Fictionalism to Realism; Carola, B., Maurizio, F., Alberto, V., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2013; pp. 87–110. [Google Scholar]

- Kroon, F. Creationism and the problem of indiscernible fictional objects. In Fictional Objects; Stuart, B., Anthony, E., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Voltolini, A. The Seven Consequences of Creationism. Metaphysica 2009, 10, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voltolini, A. How Creationism Supports for Kripke’s Vichianism on Fiction. In Truth in Fiction; Franck, L., Ed.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 38–93. [Google Scholar]

- Voltolini, A. A Suitable Metaphysics for Fictional Entities. In Fictional Objects; Stuart, B., Anthony, E., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 129–146. [Google Scholar]

- Yagisawa, T. Against Creationism in Fiction. Noûs 2001, 35, 153–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvolenszky, Z. An Argument for Authorial Creation. Organon F 2015, 22, 461–487. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, T. Nonexistent Objects; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Priest, G. Creating non-existents. In Truth in Fiction; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Everett, A. The Nonexistent; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Walton, K. Mimesis as Make-Believe: On the Foundations of the Representational Arts; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Van Inwagen, P. Creatures of fiction. Am. Philos. Q. 1977, 14, 299–308. [Google Scholar]

- Kripke, S. Reference and Existence: The John Locke Lectures; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Van Inwagen, P. Existence, ontological commitment, and fictional entities. In The Oxford Handbook of Metaphysics; Michael, J.L., Dean, W.Z., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Thomasson, A.L. Fictional characters and literary practices. Br. J. Aesthet. 2003, 43, 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouillé, L. Anti-Realism about Fictional Names at Work: A New Theory for Metafictional Sentences. Organon F 2021, 28, 223–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recanati, F. Fictional reference as simulation. In Language of Fiction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021; pp. 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Yablo, S. Carnap’s Paradox and Easy Ontology. J. Philos. 2014, 111, 470–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomasson, A.L. Fictional Discourse and Fictionalisms. In Fictional Objects; Stuart, B., Anthony, E., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 255–274. [Google Scholar]

- Thomasson, A.L. Ontology Made Easy; OUP: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Quine, W.V.O. On What There Is. In The Pragmatism Reader: From Peirce Through the Present; Robert, B.T., Scott, F.A., Eds.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1948; pp. 221–233. [Google Scholar]

- Carnap, R. Empiricism, Semantics and Ontology. Rev. Int. Philos. 1950, 4, 20–40. [Google Scholar]

- Thomasson, A.L. Norms and Necessity; OUP: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rayo, A. Ontological commitment. Philos. Compass 2007, 2, 428–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, H. Two kinds of ontological commitment. Philos. Q. 2011, 61, 79–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friend, S. Real People in Unreal Contexts: Or Is There a Spy Among Us? In Empty Names, Fiction and the Puzzles of Non-Existence; Anthony, E., Thomas, H., Eds.; CSLI Publications: Stanford, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 183–203. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer, S. Language-created language-independent entities. Philos. Top. 1996, 24, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroon, F. Characterizing Non-existents. Grazer Philos. Stud. 1996, 51, 163–193. [Google Scholar]

- Berto, F. Impossible worlds and the logic of imagination. Erkenntnis 2017, 82, 1277–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priest, G. Sylvan’s Box: A Short Story and Ten Morals. Notre Dame J. Form. Log. 1997, 38, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priest, G. In Contradiction, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, G. The Varieties of Reference; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, S. Fictionalism about fictional characters. Noûs 2002, 36, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalta, E.N. Abstract Objects: An Introduction to Axiomatic Metaphysics; D. Reidel: Dordrecht, The Netherland, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Sainsbury, R.M. Fiction and Fictionalism; Routledge: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kroon, F.W. Was meinong only pretending? Philos. Phenomenol. Res. 1992, 52, 499–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searle, J.R. The Logical Status of Fictional Discourse. New Lit. Hist. 1975, 6, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, N. Nonexistence. Noûs 1998, 32, 277–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrone, E. On Fictional Characters as Types. Br. J. Aesthet. 2017, 57, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, L. Fictional Objects. Br. J. Aesthet. 2017, 57, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, T. A Place for Strangers: Towards a History of Australian Aboriginal Being; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, K. The problem of non-existents. Topoi 1982, 1, 97–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, N. Fictional Characters and Characterisations. Pacific Philos. Q. 2022, 104, 348–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamarque, P. Works and Objects: Explorations in the Metaphysics of Art; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, L. Repeatable Artworks as Created Types. Br. J. Aesthet. 2012, 53, 461–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).