1. Introduction

Post-quantum cryptography is a new direction in the last two decades after the thread of polynomial quantum algorithms of Shor [

1], which totally broke the currently most widely-used public key cryptosystems such as RSA [

2], DSA [

3], and ECC [

4]. It has received much more attention recently after the call of NIST [

5] for proposals of post-quantum cryptosystems to be standardized in the near future. There have been a number of submissions for the first round [

6], and the first NIST conference has been recently held for discussions [

7].

Multivariate cryptography is one of the main candidates for this standardization [

5,

6]. These schemes are in general very fast and require only modest computational resources, which can be used on low-cost devices like smart cards and RFID chips [

8,

9]. Multivariate schemes were first proposed by Matsumoto and Imai in the mid-1980s [

10]. Since then, there has been a rich development of designing multivariate schemes in several directions, e.g., BigField or SingleField schemes. The first SingleField signature scheme was the Oil and Vinegar (OV) signature scheme, introduced by Patarin after he broke the Matsumoto–Imai scheme [

11]. Soon after, Patarin broke the OV schemes and introduced a variant [

12], which is called the Unbalanced Oil and Vinegar (UOV) scheme. After around two decades, UOV schemes were still secure up to the choices of parameters. While the signature generation of UOV is very efficient, it has a very large public key. To deal with this, several improvements have been suggested. The first improvement was made by Ding and Schmidt [

13], who proposed the Rainbow signature scheme, which can be seen as a multi-layer version of UOV with smaller keys and shorter signatures. The Rainbow signature scheme has remained secure for more than a decade and has been submitted as a candidate for the NIST standardization competition [

6].

In practice, digital certificates linking public keys with identities of users are needed, and this fact leads to some drawbacks in efficiency and simplicity. For this reason, the alternative framework of identity-based cryptography was introduced by Shamir [

14]. The idea is that the public key of a user can be directly derived from his/her identity, and therefore, digital certificates are avoidable. Shamir already proposed an Identity-Based Signature scheme (IBS), but it took a while until the first identity-based encryption arrived [

15]. In the area of multivariate cryptography, there has been only one proposal in the area of identity-based cryptography, that is the identity-based signature scheme IBUOV based on the UOV scheme [

16]. However, the authors of IBUOV simply used the standard version of UOV, which is not Existential Unforgeability under Chosen-Message Attack (EU-CMA) secure. This implies that the constructed IBS scheme is also not EU-CMA secure. Moreover, they also proposed the wrong parameters with the corresponding desired security level, as well as computed the wrong the corresponding key sizes.

In this paper, we adapt the method of Shamir to instantiate an identity-based signature scheme based on a provable version of Rainbow, which we call IBS-Rainbow. Since our Rainbow scheme is EU-CMA secure, the resulting IBS-Rainbow is also EU-CMA secure. In addition, we also adapt a provable UOV scheme in [

17] to IBUOV, revise the parameter choice for IBUOV, and compare with our IBS-Rainbow scheme. As a result, our IBS-Rainbow scheme is more efficient than IBUOV in terms of both key sizes and signature sizes.

The paper is organized as follows. We recall some definitions of digital signatures and identity-based signatures in

Section 2. We also present the construction of an IBS scheme from a digital signature scheme. In

Section 3, we present some basics of multivariate cryptography and recall the UOV and Rainbow schemes.

Section 4 is devoted o the modified versions of UOV and Rainbow, which are proven to be EU-CMA secure. Attacks against Rainbow are also presented. In

Section 5, we present the construction of our IBS-Rainbow scheme and the parameter choices.

Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Preliminaries

In this section, we first recall some basic notions on digital signatures and identity-based signatures and a transformation from a digital signature into an identity-based signature.

An Identity-Based Signature () scheme is a tuple of polynomial-time algorithms . The first three are randomized, but the last one. The trusted key distribution center runs the setup algorithm on input to obtain a master public and secret key . To generate the secret signing key for the user with identity , it runs the key derivation algorithm on inputs and . On input and a message M, the signing algorithm returns a signature of M. On inputs , the verification algorithm returns one if is valid for and M and returns zero otherwise. Correctness requires that with a probability of one for all and whenever the keys are generated as indicated above.

For security, we follow the notion of Existential Unforgeability under Chosen-Message and chosen-identity Attack (EU-CMA). It is defined through a game with a forger F and parameterized with the security parameter k. The experiments begin with the generation of a fresh master public and secret key pair . The forger F is run on the input of the master public key and has access to the following oracles:

: on the input identity , this oracle returns a secret signing key .

: on the input identity and a message M, this oracle returns a signature where .

At the end of its execution, the forger outputs identity , message , and a forged signature . The forger is said to win the game if and F never queried or . The advantage is defined to be the probability that F wins the game, and is said to be EU-CMA secure if is negligible in k for all polynomial-time forgers F, i.e., for all , there exists such that for all .

A Standard Signature () scheme consists of three polynomial-time algorithms . The randomized key generation algorithm KeyGen, on input , generates a key pair . The signer creates a signature on a message M via , and the verifier can check the validity of a signature by testing whether . It is required that for all messages M, with a probability of one.

The security notion for a signature scheme is defined through the notion of EU-CMA, described as the following game with a forger F. The forger is run with a fresh public key as an input and is given access to a signing oracle for the corresponding secret key . It is said to win the game if it can output a pair such that and it never queried from the signing oracle. The advantage is defined as the probability that F wins this game. is said to be EU-CMA secure if is a negligible function in k for all polynomial-time forger F.

Given a standard signature scheme , one can build a certificate-based IBS scheme as the following.

: Run to obtain .

: , ; and return .

: Parse as ; compute ; and return .

: Parse as , and check if both and are satisfied, then return one, otherwise zero.

One can see that if

is EU-CMA, then the constructed

above is also EU-CMA; see [

18] for more details and the references therein. In this paper, we will present a multivariate signature scheme that is EU-CMA and apply the above transformation to construct an EU-CMA-secure IBS scheme.

3. Multivariate Public Key Cryptography

In this section, we recall some basic concepts of multivariate public key cryptography. The basic objects of multivariate cryptography are systems of multivariate quadratic polynomials over a finite field

K. The security of multivariate schemes is based on the

MQ-problem, which asks for a solution of a given system of multivariate quadratic polynomials over the field

K. The MQ-problem has been proven to be NP-hard even for quadratic polynomials over the field

[

19].

To build a multivariate public key cryptosystem, one starts with an easily-invertible quadratic map (central map). To hide the structure of in the public key, one composes it with two invertible affine (or linear) maps and . The public key is therefore given by . The private key consists of and .

In this paper, we consider multivariate signature schemes. For these schemes, we require

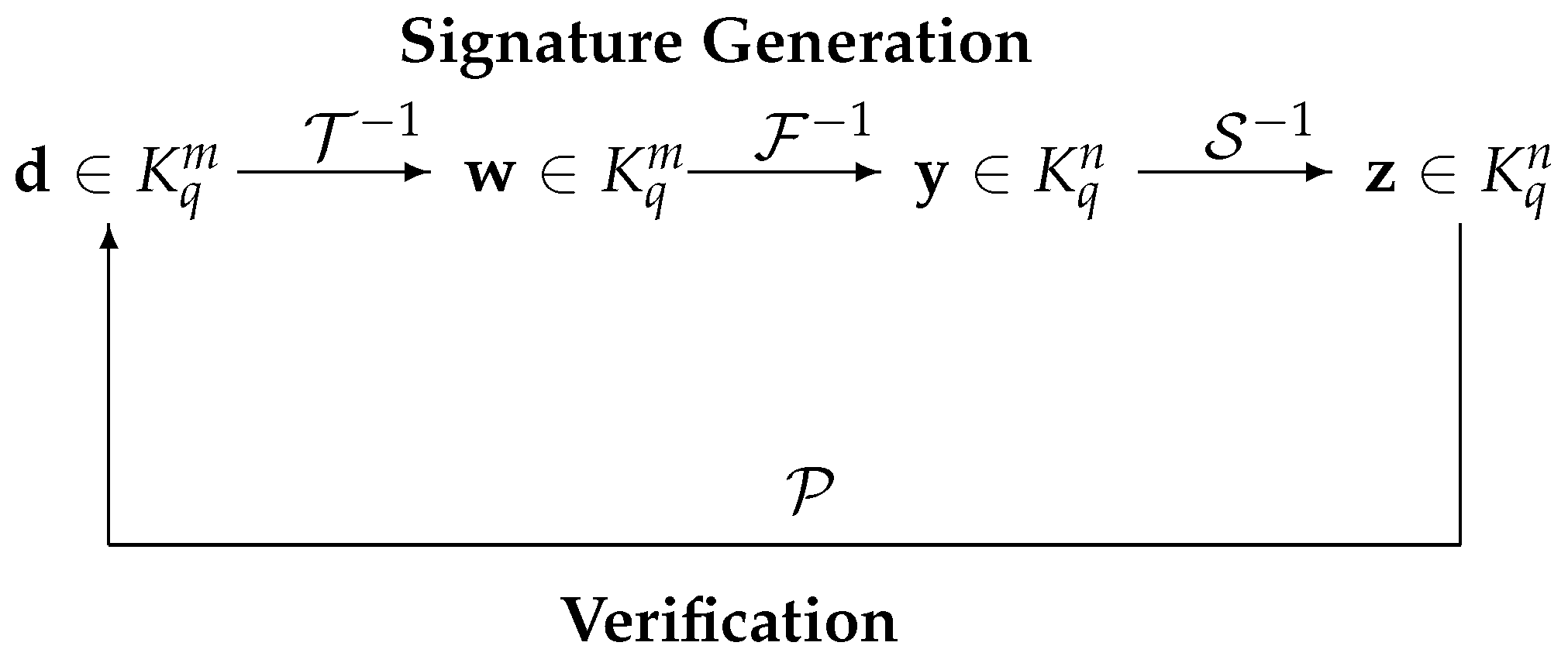

, which ensures that every message has a signature. The signature generation and verification are as the following, which is depicted in

Figure 1.

Signature generation: To generate a signature for a message (or its hash value) , one computes recursively and . Then, is the signature of the message . Here, means finding one (of possibly many) pre-image of under the central map .

Signature verification: To check the authenticity of a signature , the verifier simply computes . If the result is equal to the message , the signature is accepted, otherwise rejected.

3.1. Unbalanced Oil and Vinegar Signature Scheme

Let

be the finite field with

q elements, and let

with

positive integers. An oil-vinegar quadratic polynomial over

K is of the form:

with coefficients

. The variables

are called vinegar variables and

the oil variables. Note that in an oil-vinegar polynomial, the oil and vinegar variables are not fully mixed, i.e., there are no quadratic terms

for oil variables

x. A UOV scheme is constructed as the following.

The central map

consists of

o oil-vinegar polynomials:

where the coefficients

are in

K. Choose randomly an invertible affine map

. The public key is given by

, and the private key consists of

and

.

To sign a message , we do the following.

- (1)

Randomly choose vinegar values , and plug them into the polynomials in the central map to obtain .

- (2)

Solving the linear system with yields solution . If there is no solution, then go back to Step (1).

- (3)

Set . A signature is computed by .

A signature is accepted if , otherwise it is rejected.

The public key of the scheme consists of

o quadratic equations in

n variables; hence, the public key has size:

and the size of the private key is:

3.2. Rainbow Signature Scheme

Rainbow signature schemes [

13] are multi-layer versions of UOV schemes. For convenience, we introduce the two-layered Rainbow scheme (in the design, there is no advantage of using more than two layers). Let

be the finite field with

q elements

with

positive integers. Set

,

. The Rainbow central map

consists of the following

polynomials:

where the coefficients

are in

K. Choose randomly two invertible affine maps

and

. The public key is given by

, and the private key consists of

,

, and

.

To sign a message , we first compute and do the following.

- (1)

Choose , and plug this into the polynomials in the central map to obtain .

- (2)

Solving the linear system with yields solution . If there is no solution, then go back to Step (1).

- (3)

Plug into , and solve the linear system with to get a solution . If there is no solution, then go back to Step (1).

- (4)

Set . A signature is computed by .

A signature is accepted if , otherwise it is rejected.

The public key of the scheme consists of

m quadratic equations in

n variables; hence, the public key has size:

and the size of the private key is:

in which

.

4. Modified UOV and Rainbow

4.1. Modified UOV Signature Scheme

The standard UOV scheme in

Section 3.1 does not provide EUF-CMA security. Sakumoto et al. [

17] modified the UOV scheme into a scheme that is EU-CMA secure. The difference with the standard UOV is the use of a binary salt

r in the signature generation. The procedure is described as the following.

Key generation: With the input UOV parameters and a length l of salt, generate the public key and secret key as in the standard Rainbow. Now, the public key and secret key of the modified Rainbow are and , respectively.

Signature generation: To sign on a message , one does the following:

- (1)

Choose .

- (2)

Choose a random salt .

- (3)

Let , where is a hash function.

- (4)

Solving the linear system with yields solution . If there is no solution, then go back to Step (2).

- (5)

Set , and compute . A signature is of the form .

Verification: Given a message and a signature , one first computes and . If , then accept, otherwise reject.

It was proven in [

17] that the modified UOV is EU-CMA secure if the underlying UOV scheme is secure, and it was mentioned that the modified UOV does not degrade the efficiency too much compared to the standard UOV; see [

17] for more details.

4.2. Modified Rainbow Signature Scheme

The standard Rainbow scheme in

Section 3.2 also does not provide EUF-CMA security. Here, we present a modified version that obtained EUF-CMA security, similar to [

17] for UOV. The difference is the use of a random salt, which is a binary vector

r. Instead of generating a signature for

, one generates a signature for

. The procedure is as follows.

Key generation: With input Rainbow parameters and a length l of salt, generate the public key and secret key as in the standard Rainbow. Now, the public key and secret key of the modified Rainbow are and , respectively.

Signature generation: To sign on a message , one does the following:

- (1)

Choose , and plug this into the polynomials in the central map to obtain until the first linear polynomials are non-degenerated, i.e., the corresponding coefficient matrix is invertible.

- (2)

Choose a random salt .

- (3)

Let .

- (4)

Compute .

- (5)

Solving the linear system with yields solution . This always has a solution since Step (1).

- (6)

Plug into , and solve the linear system with to get a solution . If there is no solution, then go back to Step (2).

- (7)

Set , and compute . A signature is of the form .

Verification: Given a message and a signature , one first computes and . If then accept, otherwise reject.

One easily proves the EU-CMA security of the modified Rainbow by following the same procedure as for the modified UOV scheme in [

17].

4.3. Attacks

In this section, we review all currently-known (classical) attacks against Rainbow.

4.3.1. Direct Attacks

It is also well known that Rainbow schemes behave similarly to random systems, and therefore, we can estimate the complexity of direct attack against Rainbow as (cf. [

20]):

where

is the linear algebra constant of solving a linear system and

is the degree of regularity of the system, which can be estimated as the smallest

d for which the coefficient of

in the expression:

is non-positive.

4.3.2. The Rank Attacks

There are Minrank [

21] and Highrank [

22] attacks. The Minrank [

21] attack tries to find a linear combination of the public key polynomials of minimal rank. In the case of Rainbow, such a minimal rank is

, which corresponds to a linear combination of polynomials in the first layer of the central map. The complexity is estimated as:

The Highrank [

22] attack tries to identify variables that appear the lowest number of times in the polynomials of the central map. In the case of Rainbow, those are the oil variables of the last layer. The complexity of the Highrank attack is estimated as:

4.3.3. UOV Attack

One can consider Rainbow as a UOV scheme with

and

, and hence, it can be attacked by the UOV attack. Its goal is to find the pre-image of the oil subspace

under the affine transformation

. The complexity of this attack is estimated as:

4.3.4. Rainbow-Band-Separation Attack

The Rainbow-Band-Separation (RBS) attack [

23] tries to find linear transformations

and

that transform the public polynomials into ones of the form of polynomials in the central map of Rainbow, and hence find an equivalent key to forge a signature. To do this, one has to solve

equations in

n variables. In our paper, we used the field

, and we followed [

20] to choose

so that the complexity of the RBS attack against Rainbow was at least the complexity of the direct attack.

4.3.5. Collision Attacks against the Hash Function

Note that the modified Rainbow scheme uses hash function . Hence, in order to prevent a collision attack against the hash function, we need the number m of public equations satisfying that is greater than the desired security level.

5. Identity-Based Signature Schemes Based on Rainbow

In this section, we follow the construction in

Section 2 to instantiate an identity-based signature scheme based on the modified Rainbow scheme from

Section 4.2. We call the scheme IBS-Rainbow.

5.1. Construction

Let

be parameters as in

Section 3.2. Let

,

,

, and

. Let

be a hash function and

l be the length of salts. The scheme IBS-Rainbow consists of four algorithms

defined as follows.

Master-key generation:.

The algorithm selects a central map for a Rainbow scheme with parameters as above, two invertible affine maps , , and computes . It outputs the master secret key and the master public key .

User-key extraction:.

For a user

I, the algorithm

generates a new Rainbow scheme with secret key

and public key

such that

is different from the master secret key

. Then, it executes

. Next, it uses the knowledge of master secret key

to find a signature

for the message

as in

Section 4.2. Note that

. Let

. The algorithm then returns the secret key for the user

I as

.

Signature generation:.

Given a message

M, the algorithm uses the knowledge of

to find a signature

for

M from the system

as in

Section 4.2. It outputs the signature

.

Verification:.

Given a signature of a message M of the user I. Parse as . Note that , and . We then compute , . If both and , then it outputs one, which means the signature is accepted. Otherwise, it outputs zero and rejects the signature.

The correctness is easy to check. Since we are using the modified Rainbow scheme in

Section 4.2, which is EU-CMA secure, the resulting IBS-Rainbow scheme is also EU-CMA secure.

5.2. Parameters

We next give a choice of parameters and compute the key sizes of the IBS-Rainbow. We also revised the IBUOV scheme in [

16] (note that the construction of the IBUOV scheme also follows the same route as in

Section 5.1 with the core modified Rainbow (

Section 4.2) replaced by the normal UOV scheme (the scheme in

Section 4.1 without using salts and the hash function in Steps (2) and (3) of the signature generation process); see

Appendix A for more details.) and compared it with IBS-Rainbow.

First, for the EU-CMA security of the system, we needed to ensure that no salt was used for more than one signature. Under the assumption of up to signatures being generated with the system, we chose the length l of the salt to be bit, independent of the security level.

Second, we chose two popular base fields for

K, which were

and

. We aimed for the security level to be the standard 128-bit. The choice of parameters had to ensure that the corresponding Rainbow scheme was secure against all attacks mentioned in

Section 4.3, i.e., for a choice of parameters, the complexities of all attacks in

Section 4.3 had to be at least

for corresponding security level

k (

).

The details are illustrated in

Table 1. We write

, meaning that

is the parameter of the UOV scheme used in IBUOV. Similarly, we write

with

the parameter of the Rainbow scheme used in IBS-Rainbow.

As we see from

Table 1, using Rainbow, we can reduce the key sizes and signature sizes. In particular, we reduced the signature sizes up to

. For the user’s secret key size, we can reduce up to

and

for the fields

and

, respectively.