Monolithically-Integrated Single-Photon Avalanche Diode in a Zero-Change Standard CMOS Process for Low-Cost and Low-Voltage LiDAR Application

Abstract

:1. Introduction

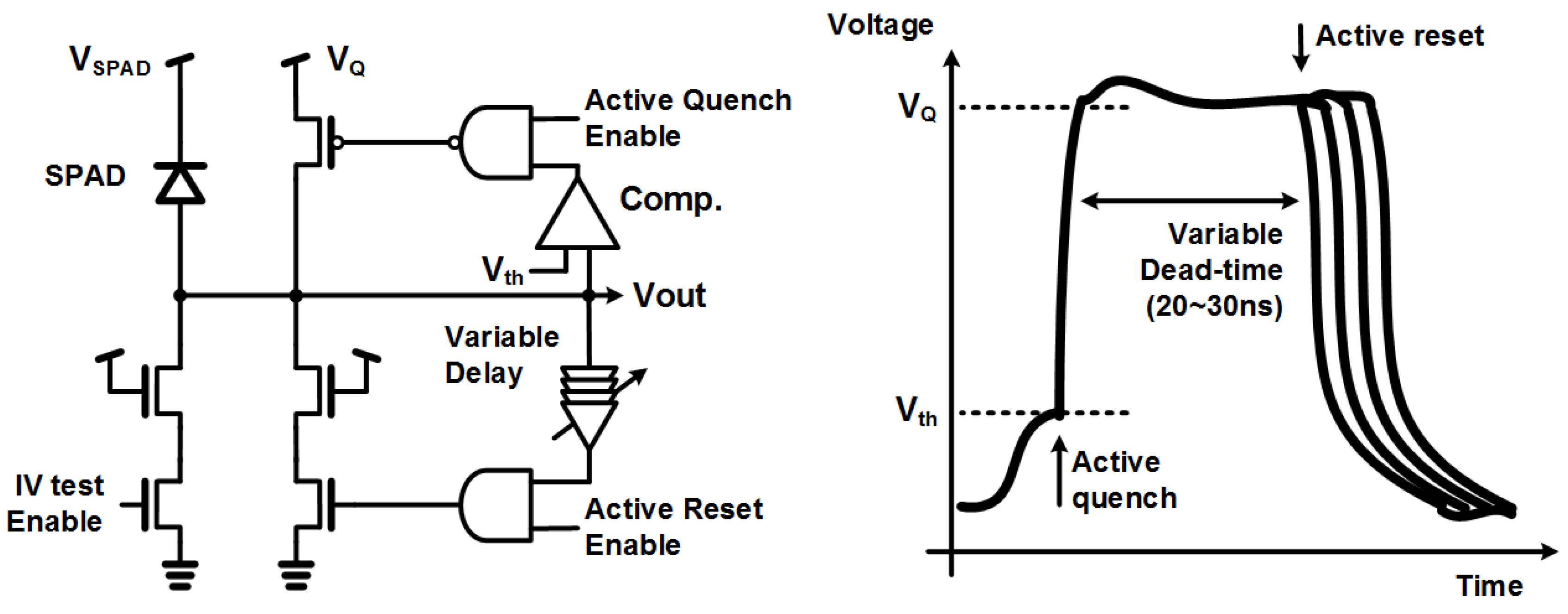

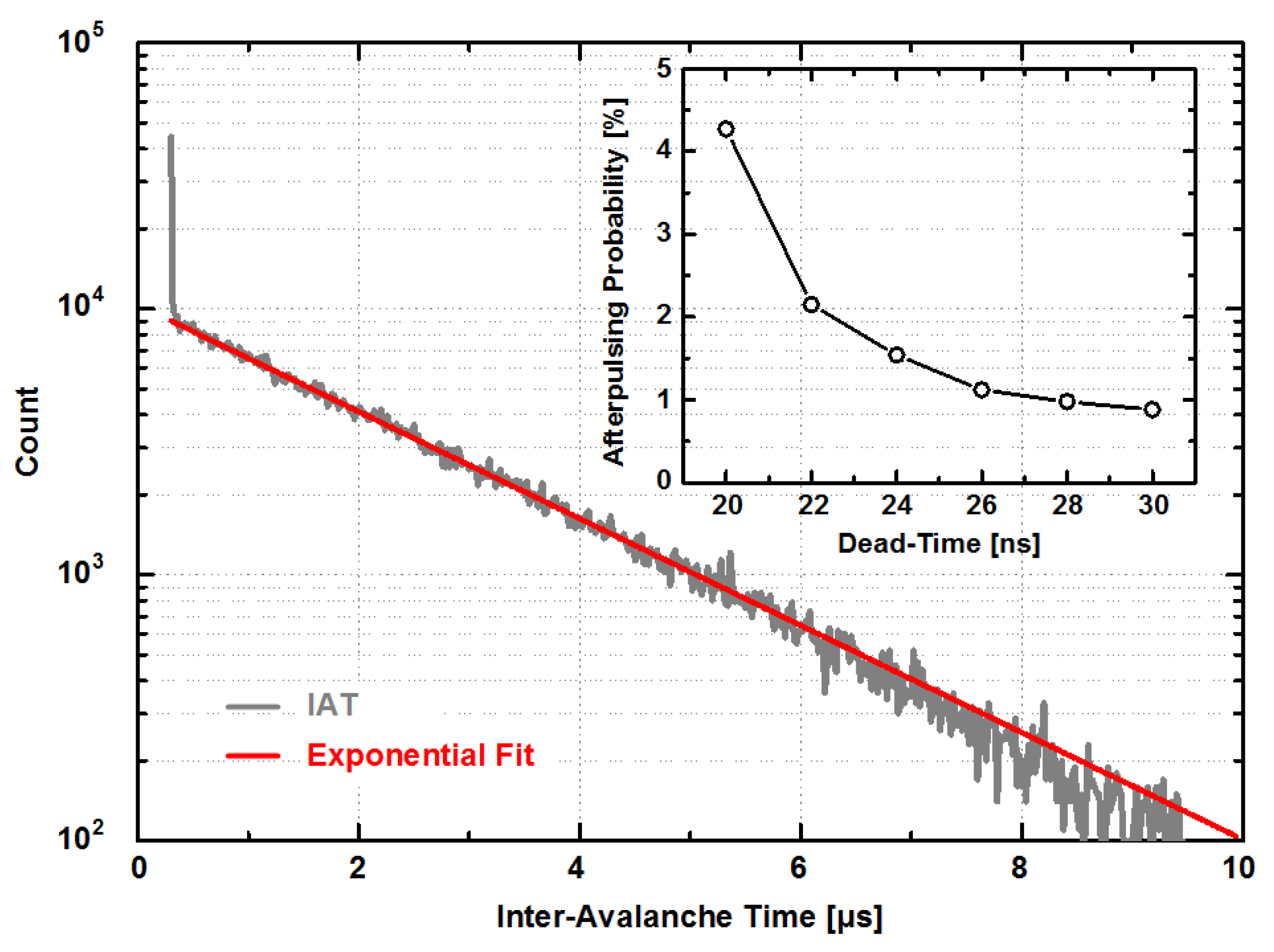

2. Single-Photon Sensor

3. Measurement Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hadfield, R.H. Single-photon detectors for optical quantum information applications. Nat. Photon. 2009, 3, 696–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruschini, C.; Homulle, H.; Charbon, E. Ten years of biophotonics single-photon SPAD imager applications – retrospective and outlook. In Proceedings of the Advanced Photon Counting Techniques XI, Anaheim, CA, USA, 9–13 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ghioni, M.; Gulinatti, A.; Rech, I.; Zappa, F.; Cova, S. Progress in silicon single-photon avalanche diodes. IEEE J. Sel. Topics Quantum Electron. 2007, 13, 852–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-J.; Sun, P.; Charbon, E. A first single-photon avalanche diode fabricated in standard SOI CMOS technology with a full characterization of the device. Opt. Express 2015, 23, 13200–13209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellegrini, S.; Rae, B. Fully industrialised single photon avalanche diodes. In Proceedings of the Advanced Photon Counting Techniques XI, Anaheim, CA, USA, 9–13 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini, S.; Rae, B.; Pingault, A.; Golanski, D.; Jouan, S.; Lapeyre, C.; Mamdy, B. Industrialised SPAD in 40 nm Technology. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM), San Francisco, CA, USA, 2–6 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Niclass, C.; Soga, M.; Matsubara, H.; Kato, S.; Kagami, M. A 100-m range 10-frame/s 340x96-pixel time-of-flight depth sensor in 0.18-μm CMOS. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2013, 48, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niclass, C.; Gersbach, M.; Henderson, R.; Grant, L.; Charbon, E. A single photon avalanche diode implemented in 130-nm CMOS technology. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2007, 13, 863–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, M.A.; Gersbach, M.; Yoon, H.-J.; Charbon, E. A new single-photon avalanche diode in 90nm standard CMOS technology. Opt. Express 2010, 18, 22158–22166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.D.; Wu, J.Y.; Wang, J.P.; Tsai, C.M.; Huang, Y.H.; Wu, D.R.; Lin, S.D. Single-photon avalanche diodes in 0.18-μm high-voltage CMOS technology. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 13333–13339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, E.A.G.; Grant, L.A.; Henderson, R.K. A high- performance single-photon avalanche diode in 130-nm CMOS imaging technology. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2012, 33, 1589–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerappan, C.; Charbon, E. CMOS SPAD based on photo-carrier diffusion achieving PDP > 40% from 440 to 580 nm at 4V excess bias. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 2015, 27, 2445–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Pancheri, L.; Betta, G.-F.D.; Stoppa, D. Design and characterization of a p+/n-well SPAD array in 150nm CMOS process. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 12765–12778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faramarzpour, N.; Deen, M.J.; Shirani, S.; Fang, Q. Fully integrated single photon avalanche diode detector in standard CMOS 0.18-μm technology. IEEE Tran. Electron Devices 2008, 55, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancheri, L.; Stoppa, D. Low-noise single photon avalanche diodes in 0.15 μm CMOS technology. In Proceedings of the 2011 European Solid-State Device Research Conference (ESSDERC), Helsinki, Finland, 12–16 September 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palubiak, D.P.; El-Desouki, M.M.; Marinov, O.; Deen, M.J.; Fang, Q. High-speed, single photon avalanche photodiode imager for biomedical applications. IEEE Sens. J. 2011, 11, 2401–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, H.; Hsu, M.J.; Esener, S. STI-bounded single-photon avalanche diode in a deep-submicrometer CMOS technology. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2006, 27, 887–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavia, J.M.; Wolf, M.; Charbon, E. Measurement and modeling of microlenses fabricated on single-photon avalanche diode arrays for fill factor recovery. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 4202–4213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, A.; Eshkoli, A.; Feningstein, A.; Jackson, C.; Nemirovsky, Y. Design considerations of CMOS Si photomultiplier for long range LIDAR. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Microwaves, Antennas, Communications and Electronic Systems (COMCAS), Tel Aviv, Israel, 13–15 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Palubiak, D.P.; Li, Z.; Deen, M.J. Afterpulsing characteristics of free-running and time-gated SPADs in 130nm CMOS. IEEE Tran. Electron Devices 2015, 62, 3727–3733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.M. Optimization of eyesafe avalanche photodiode lidar for automobile safety and autonomous navigation systems. Optical Eng. 2017, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| This Work | [13] | [14] | [15] | [16] | [10] | [11] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technology | 0.18-μm | 0.15-μm | 0.18-μm | 0.15-μm | 0.13-μm | 0.18-μm | 0.13-μm |

| Process | Standard CMOS | Standard CMOS | Standard CMOS | Standard CMOS | Standard CMOS | High-Voltage CMOS | CMOS Image Sensor |

| Junction Structure | P+/ N-well | P+/ N-well | P+/ N-well | P+/ N-well | N+/ P-well | Deep P-well/ Buried-N | Deep N-well/ P-sub |

| Guard-Ring Structure | P-well | Deep N-well | P-well | P epi | N-well | P-well | P-epi Virtual |

| Active Area | 50.24 μm2 | 97.12 μm2 | 90 μm2 | 78.5 μm2 | 100 μm2 | 100 μm2 | 16 μm2 |

| Shape | Circle | Square | Octagon | Circle | Square | Circular | Circular |

| VBR | 9.98 V | 18.01V | 10.2 V | 16.1 V | 11.3 V | 49.9 V | 20 V |

| Vex | 2 V | 3 V | 2 V | 3.5 V | 2.2 V | 5 V | 2 V |

| Normalized DCR | 10300 cps/μm2 | 0.4 cps/μm2 | 7780 cps/μm2 @ 0.5 Vex | 1.53 cps/μm2 | 1000 cps/μm2 | 0.68 cps/μm2 | 1.125 cps/μm2 |

| Afterpulsing Probability (Dead Time) | 1% (30 ns) | 0.85% (150 ns) | N/A | 0.45% (100 ns) | N/A | 1.6% (20 ns) | 4% @ 12Vex (N/A) |

| PDP Peak (λ) | 30.4% (530 nm) | 27.5% (450 nm) | 5.5% (450 nm) | 25% (470 nm) | 13% (570 nm) | 22% (570 nm) | 72% @ 12Vex (550 nm) |

| PDP @ 905 nm | 3.8% | 2% | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2.8% | 5% |

| FWHM Timing Jitter (λ) | 92 ps (905 nm) | 42 ps @ 4Vex (831nm) | N/A | 92 ps (470 nm) | N/A | 200 ps (720 nm) | N/A |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rhim, J.; Zeng, X.; Huang, Z.; Chalamalasetti, S.R.; Fiorentino, M.; Beausoleil, R.; Lee, M.-J. Monolithically-Integrated Single-Photon Avalanche Diode in a Zero-Change Standard CMOS Process for Low-Cost and Low-Voltage LiDAR Application. Instruments 2019, 3, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/instruments3020033

Rhim J, Zeng X, Huang Z, Chalamalasetti SR, Fiorentino M, Beausoleil R, Lee M-J. Monolithically-Integrated Single-Photon Avalanche Diode in a Zero-Change Standard CMOS Process for Low-Cost and Low-Voltage LiDAR Application. Instruments. 2019; 3(2):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/instruments3020033

Chicago/Turabian StyleRhim, Jinsoo, Xiaoge Zeng, Zhihong Huang, Sai Rahul Chalamalasetti, Marco Fiorentino, Raymond Beausoleil, and Myung-Jae Lee. 2019. "Monolithically-Integrated Single-Photon Avalanche Diode in a Zero-Change Standard CMOS Process for Low-Cost and Low-Voltage LiDAR Application" Instruments 3, no. 2: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/instruments3020033

APA StyleRhim, J., Zeng, X., Huang, Z., Chalamalasetti, S. R., Fiorentino, M., Beausoleil, R., & Lee, M.-J. (2019). Monolithically-Integrated Single-Photon Avalanche Diode in a Zero-Change Standard CMOS Process for Low-Cost and Low-Voltage LiDAR Application. Instruments, 3(2), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/instruments3020033