Sexual Fantasies across Gender and Sexual Orientation in Young Adults: A Multiple Correspondence Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

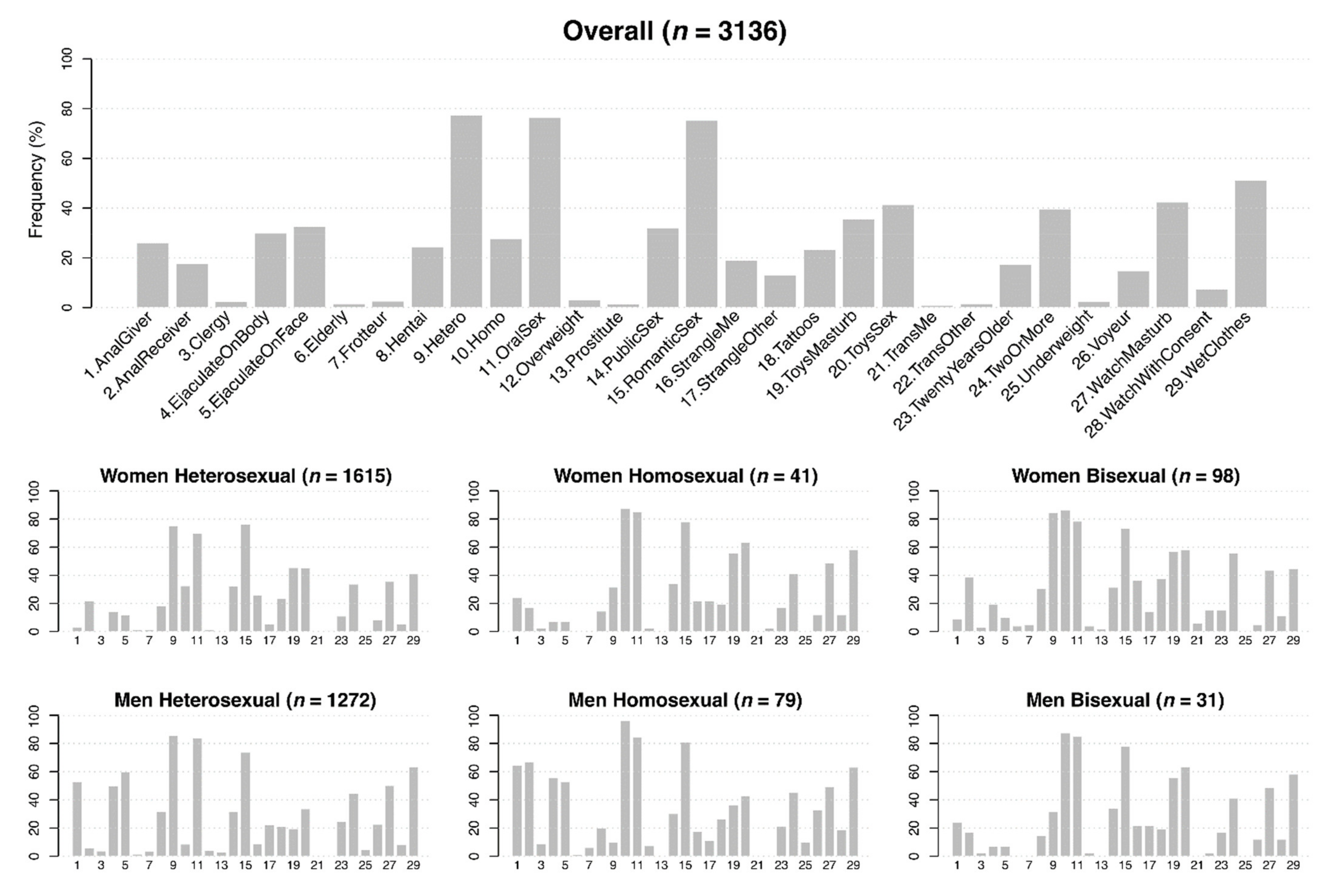

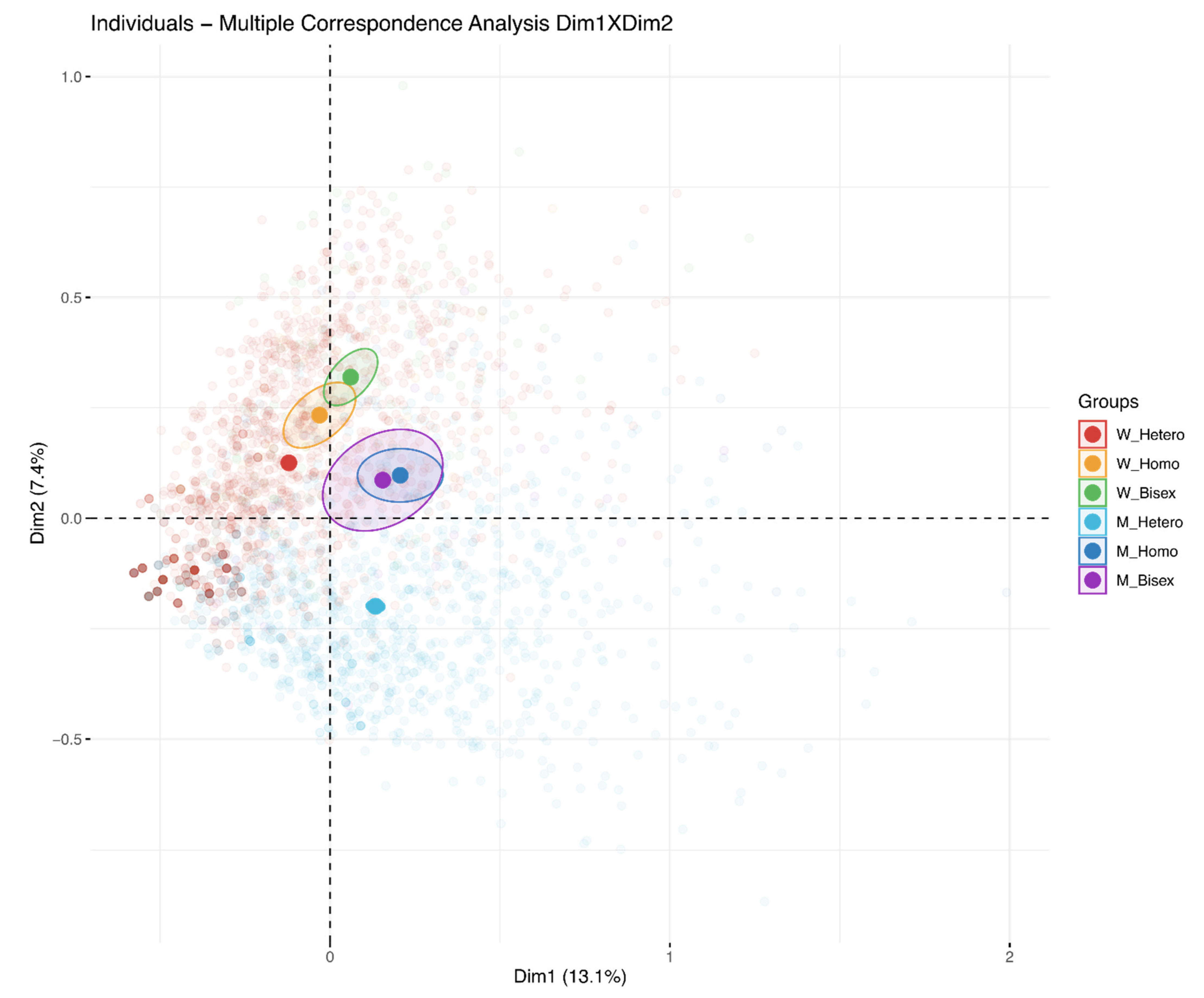

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Purifoy, F.E.; Grodsky, A.; Giambra, L.M. The relationship of sexual daydreaming to sexual activity, sexual drive, and sexual attitudes for women across the life-span. Arch. Sex. Behav. 1992, 21, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitenberg, H.; Henning, K. Sexual fantasy. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 469–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bivona, J.M.; Critelli, J.W.; Clark, M.J. Women’s rape fantasies: An empirical evaluation of the major explanations. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2012, 41, 1107–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyal, C.C.; Cossette, A.; Lapierre, V. What exactly is an unusual sexual fantasy? J. Sex. Med. 2015, 12, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, B.J.; Symons, D. Sex differences in sexual fantasy: An evolutionary psychological approach. J. Sex Res. 1990, 27, 527–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnbaum, G.E.; Kanat-Maymon, Y.; Mizrahi, M.; Recanati, M.; Orr, R. What fantasies can do to your relationship: The effects of sexual fantasies on couple interactions. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2019, 45, 461–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, G.P.; Vale, F.B.C.; Vieira, I.; da Silva Filho, A.L.; Abuhid, C.; Geber, S. COVID-19 and sexuality: Reinventing intimacy. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2020, 49, 2735–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayalon, L.; Gewirtz-Meydan, A.; Levkovich, I. Older adults’ coping strategies with changes in sexual functioning: Results from qualitative research. J. Sex. Med. 2019, 16, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, G.D. Measurement of sex fantasy. Sex. Marital Ther. 1988, 3, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzani, A.; Prunas, A. Sexual fantasy of cisgender and nonbinary individuals: A quantitative study. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2020, 46, 763–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, A.F.; Visser, B.A.; Pozzebon, J.A. Gender differences in object of desire self-consciousness sexual fantasies. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2015, 44, 2299–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tortora, C.; D’Urso, G.; Nimbi, F.M.; Pace, U.; Marchetti, D.; Fontanesi, L. Sexual fantasies and stereotypical gender roles: The influence of sexual orientation, gender and social pressure in a sample of Italian young-adults. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bártová, K.; Androvičová, R.; Krejčová, L.; Weiss, P.; Klapilová, K. The Prevalence of paraphilic interests in the Czech population: Preference, arousal, the use of pornography, fantasy, and behavior. J. Sex Res. 2021, 58, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.D.; Lang, R.J. Sex differences in sexual fantasy patterns. Pers. Individ. Dif. 1981, 2, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Catanese, K.R.; Vohs, K.D. Is there a gender difference in strength of sex drive? Theoretical views, conceptual distinctions, and a review of relevant evidence. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 5, 242–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurbriggen, E.L.; Yost, M.R. Power, desire, and pleasure in sexual fantasies. J. Sex Res. 2004, 41, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, D.; Janssen, E.; Graham, C.; Vorst, H.; Wicherts, J. Women’s scores on the sexual inhibition/sexual excitation scales (SIS/SES): Gender similarities and differences. J. Sex Res. 2008, 45, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yost, M.R.; Zurbriggen, E.L. Gender differences in the enactment of sociosexuality: An examination of implicit social motives, sexual fantasies, coercive sexual attitudes, and aggressive sexual behavior. J. Sex Res. 2006, 43, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, L. Girls want sex, boys want love: Resisting dominant discourses of (hetero) sexuality. Sexualities 2003, 6, 215–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmiller, J.J. Fantasies about consensual nonmonogamy among persons in monogamous romantic relationships. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2020, 49, 2799–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, J.C.; Barlow, D.H. Self-reported frequency of sexual urges, fantasies, and masturbatory fantasies in heterosexual males and females. Arch. Sex. Behav. 1990, 19, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, J.H.; Allensworth, D.D.; Hillman, K.S. Comparison of sexual fantasies of homosexuals and of heterosexuals. Psychol. Rep. 1985, 57, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimbi, F.M.; Ciocca, G.; Limoncin, E.; Fontanesi, L.; Uysal, Ü.B.; Flinchum, M.; Tambelli, R.; Jannini, E.A.; Simonelli, C. Sexual desire and fantasies in the LGBT+ community: Focus on lesbian women and gay men. Curr. Sex. Health Rep. 2020, 12, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhugra, D.; Rahman, Q.; Bhintade, R. Sexual fantasy in gay men in India: A comparison with heterosexual men. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2006, 21, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.D.; Parks, C.W. Lesbian and bisexual women’s sexual fantasies, psychological adjustment, and close relationship functioning. J. Psychol. Hum. Sex. 2004, 15, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmiller, J.J.; Ley, D.; Savage, D. The psychology of gay men’s cuckolding fantasies. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2018, 47, 999–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, T.A.; Jeglic, E.L. Attenuation of deviant sexual fantasy across the lifespan in United States adult males. Psychiatry, Psychol. Law 2020, 27, 246–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindley, L.M.; Anzani, A.; Prunas, A.; Galupo, M.P. Sexual fantasy across gender identity: A qualitative investigation of differences between cisgender and non-binary people’s imagery. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2020, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H.S.; Park, C.M.; Lee, S.W. The clinical relevance of sex hormone levels and sexual activity in the ageing male. BJU Int. 2002, 89, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kinsey, A.C.; Pomeroy, W.B.; Martin, C.E. Sexual Behavior in the Human Male; Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1948; Available online: https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.6.894 (accessed on 2 December 2020).

- Lê, S.; Josse, J.; Husson, F. FactoMineR: An R package for multivariate analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lehmiller, J.J. Tell Me What You Want: The Science of Sexual Desire and How it Can Help You Improve Your Sex Life; Da Capo Lifelong Books: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tripodi, F.; Eleuteri, S.; Giuliani, M.; Rossi, R.; Livi, S.; Petruccelli, I.; Petruccelli, F.; Daneback, K.; Simonelli, C. Unusual online sexual interests in heterosexual Swedish and Italian university students. Sexologies 2015, 24, e84–e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonsen, A.N.; Zdaniuk, B.; Yule, M.; Brotto, L.A. Ace and Aro: Understanding differences in romantic attractions among persons identifying as asexual. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2020, 49, 1615–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| # | Variable Name | Content of Fantasy |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | AnalGiver | Anal sex as giver (included with strap-on) |

| 2 | AnalReceiver | Anal sex as receiver |

| 3 | Clergy | Clergymen/women (e.g., priests, nuns etc.) |

| 4 | EjaculateOnBody | Ejaculating on my partner’s body or vice versa |

| 5 | EjaculateOnFace | Ejaculating on my partner’s face or vice versa |

| 6 | Elderly | Having sex with elderly people |

| 7 | Frotteur | Rubbing myself against a non-consenting person |

| 8 | Hentai | Cartoons with sexual contents (for example, hentai) |

| 9 | Hetero | Having sex with a person of a different sex |

| 10 | Homo | Having sex with a person of the same sex as myself |

| 11 | OralSex | Oral sex (fellatio, cunnilingus) |

| 12 | Overweight | Having sex with overweight/obese people |

| 13 | Prostitute | Paying a prostitute for sex |

| 14 | PublicSex | Having sex in public places (for example parks, toilets, etc.) |

| 15 | RomanticSex | Having romantic and intimate sex |

| 16 | StrangleMe | Being strangled by the partner while having sex |

| 17 | StrangleOther | Strangling the partner while having sex |

| 18 | Tattoos | Having sex with someone who has tattoos |

| 19 | ToysMasturb | Using sex toys during masturbation |

| 20 | ToysSex | Using sex toys during sex |

| 21 | TransMe | Having sex while dressed as someone of the opposite sex |

| 22 | TransOther | Having sex with someone dressed as someone of the opposite sex |

| 23 | TwentyYearsOlder | Having sex with someone at least twenty years older than me |

| 24 | TwoOrMore | Having sex with other two or more people at the same time |

| 25 | Underweight | Having sex with underweight people |

| 26 | Voyeur | Watching someone naked/having sex without them knowing |

| 27 | WatchMasturb | Watching someone masturbating |

| 28 | WatchWithConsent | Watching someone naked/having sex with their consent |

| 29 | WetClothes | Watching someone wearing wet clothes |

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Women | 1754 | 55.9 |

| Heterosexual | 1615 | 51.5 |

| Homosexual | 41 | 1.3 |

| Bisexual | 98 | 3.1 |

| Men | 1382 | 44.1 |

| Heterosexual | 1272 | 40.6 |

| Homosexual | 79 | 2.5 |

| Bisexual | 31 | 1.0 |

| Highest educational level | ||

| Postgraduate degree | 836 | 26.7 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 1277 | 40.7 |

| High school | 998 | 31.8 |

| Middle school | 25 | 0.8 |

| Location | ||

| Northern Italy | 1131 | 36.1 |

| Central Italy | 1377 | 43.9 |

| Southern Italy | 628 | 20.0 |

| Total | 3136 | 100 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nese, M.; Riboli, G.; Brighetti, G.; Visciano, R.; Giunti, D.; Borlimi, R. Sexual Fantasies across Gender and Sexual Orientation in Young Adults: A Multiple Correspondence Analysis. Sexes 2021, 2, 523-533. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes2040041

Nese M, Riboli G, Brighetti G, Visciano R, Giunti D, Borlimi R. Sexual Fantasies across Gender and Sexual Orientation in Young Adults: A Multiple Correspondence Analysis. Sexes. 2021; 2(4):523-533. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes2040041

Chicago/Turabian StyleNese, Mattia, Greta Riboli, Gianni Brighetti, Raffaele Visciano, Daniel Giunti, and Rosita Borlimi. 2021. "Sexual Fantasies across Gender and Sexual Orientation in Young Adults: A Multiple Correspondence Analysis" Sexes 2, no. 4: 523-533. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes2040041

APA StyleNese, M., Riboli, G., Brighetti, G., Visciano, R., Giunti, D., & Borlimi, R. (2021). Sexual Fantasies across Gender and Sexual Orientation in Young Adults: A Multiple Correspondence Analysis. Sexes, 2(4), 523-533. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes2040041