Abstract

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) lists 1571 as the year of the first recorded use of the English word ‘masculinity’; the Ancient Greek (andreia), usually translated as ‘courage’, was also used to refer to manliness. The notion of manliness or masculinity is undoubtedly older still. Yet, despite this seeming familiarity, not only is the notion proving to be highly elusive, its understanding by the society being in a constant flux, but is also one which is at the root of bitter division and confrontation, and which has tangible and far-reaching real-world effects. At the same time, while masculinity has been attracting an increasing amount of attention in academia, the large body of published work seldom goes to the very foundations of the issue, failing to explicitly and with clarity reach a consensus as to how masculinity ought to be understood. Herein, I critique the leading contemporary thought, showing it to be poorly conceived and confounded, and often lacking in substance which would raise it to the level of the actionable and constructive. Hence, I propose an alternative view which is void of the observed deficiencies, and discuss how its adoption would facilitate a conciliation between the currently warring factions, focusing everybody’s efforts on addressing the actual ethical, deconfounded of specious distractions.

1. Introduction

The last century has witnessed immense social changes. In no small part, these are facilitated and sped up by technology and the present-day ability to create information (in the form of text, images, sound, video, etc.) and to communicate that information with speed across what are practically arbitrary distances. A useful analogy is that of evolution by natural section (though, it should be noted, that as with any analogy, one should be careful not to take it overly literally and to excess): most of the time, new ideas slowly spread and effect greater change by virtue of seeping expansion and accumulation; then, there are occasional significant events, akin to punctuated equilibria in evolutionary biology, which facilitate significant changes in a short period of time. Such events can be environmental in origin, as exemplified by a period of rapid evolution of mammals due to the reduced competition which followed the extinction of the dinosaurs [1]. Alternatively, equilibrium can be punctuated by the emergence of a particularly advantageous mutation which then lays ground for further accelerated adaptation and speciation, as seen in the case of antibiotic-resistant bacteria [2]. The rate of social change that we are witnessing at the present time suggests that we may be living though a period of such punctuated equilibrium, punctuated by the emergence of new ideas.

The understanding of self-identity and the associated sex-based norms is one of the many elements of our world-view which has been undergoing remarkable transformation in front of our eyes. As important concepts in the debate that has been ongoing, the notions of masculinity and femininity have themselves been undergoing intense scrutiny, their very natures being re-examined in their own right, as has their relationship with gender [3], autonomy [4], and personal freedom [5]. The former, that is, masculinity, has been receiving particularly close attention both in popular media and in the academic literature (Google Scholar retrieves twice as many articles containing the term ‘masculinity’ than those containing ‘femininity’), often being considered in the context of its claimed detrimental manifestations, in the forms such as that of ‘toxic masculinity’ [6,7,8], ‘negative masculinity’ [9], ‘harmful masculinity’ [10], ‘hegemonic masculinity’ [11,12], etc.

In the present article, I argue that much of the conflict and disagreement as regards masculinity emanates from the diversity in the manner in which these terms are understood by different individuals, and what is more, that the understandings that dominate the debate are, firstly, insufficiently nuanced and confounded by irrelevant considerations, and secondly, that these are often incoherent, inconsistent, and sophistic, void of any actionable substance. Hence, I systematically revisit the concept of masculinity (and, similarly, that of femininity), starting with a critique of the leading contemporary views, then proceed to delineate a coherent, constructive, and workable definition of the notion, and finish with a discussion of the practical consequences of the adoption of my proposal.

2. What Is Masculinity?

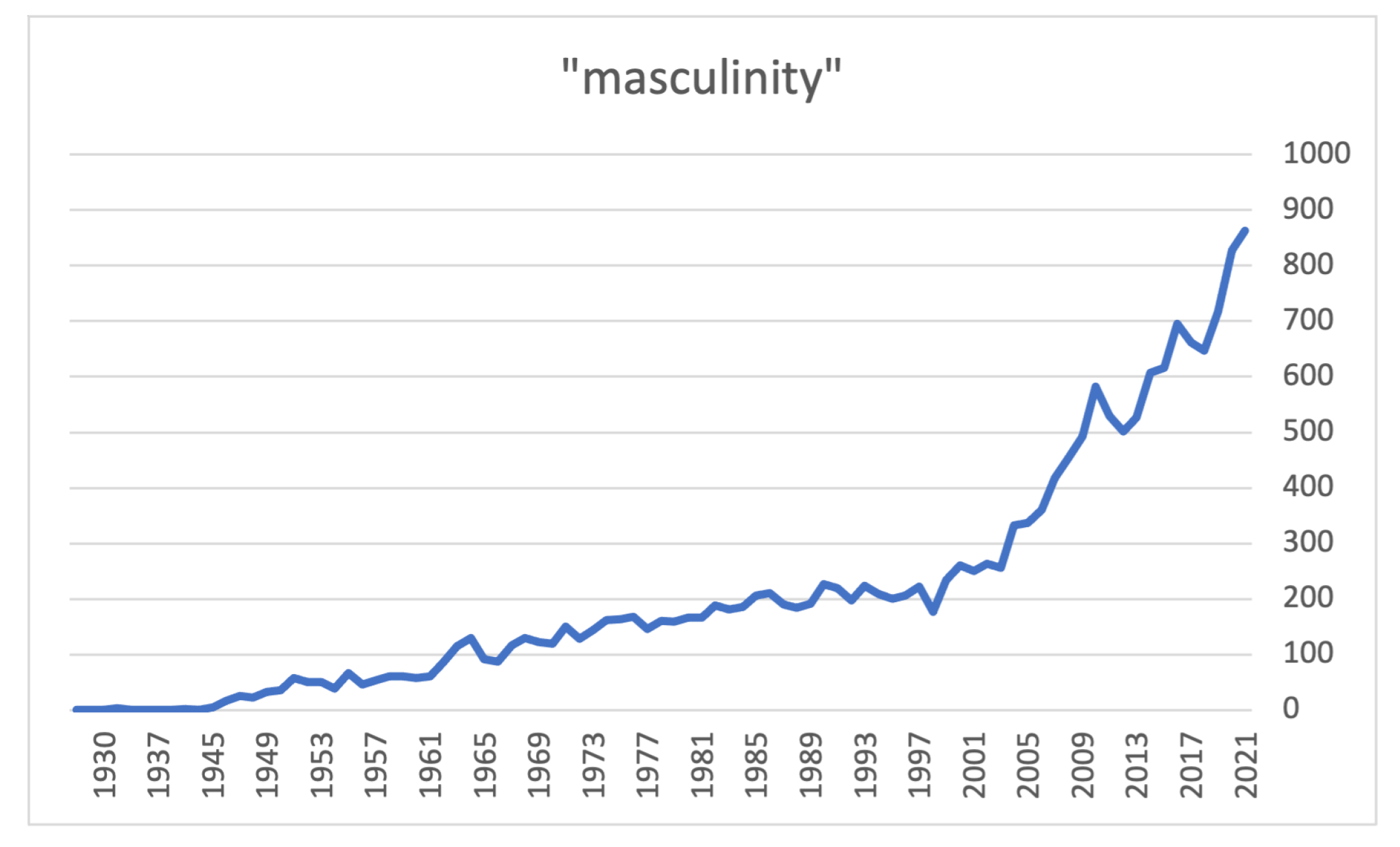

At the time of this writing, a search for ‘masculinity’ on PubMed retrieves 17,176 publications and shows a rapidly increasing number of publications referring to the notion (see Figure 1); Google Scholar, which indexes a wider range of sources, similarly retrieves approximately 1,340,000 results. Considering the sheer volume of research concerning masculinity, one would reasonably expect that the meaning of the concept is either a settled issue or one which is undergoing intense debate. Yet, this is far from the case; rather, as Spence [13] put it:

Figure 1.

Number of publications (per year) retrieved by PubMed using the search term ‘masculinity’.

“the terms masculine and feminine and masculinity and femininity have rarely been defined”.

With few exceptions, authors embark on empirical research or undertake socio-philosophical discussions contingent on the notion, without their understanding of the same being clear at all [14]. This lack of due rigour is made that much worse by a solid body of evidence that masculinity is understood in a highly diverse manner by different individuals and that this understanding often borders on trivial observations [13,15]. I contend that it is in this, that is, in the lack of a common understanding of masculinity and in the shallowness of the definition thereof that is implicitly assumed by many, where the root cause of much of the controversy surrounding the concept lies.

This may be surprising at first, but it is certainly nothing new, be it in historical or contemporaneous academic literature. Oftentimes, the potential for different understandings of the same notion is overlooked, as is the possibility of the seemingly simple being more complex than initially realized, with the discussion proceeding on the implicit assumption of some nebulous “common sense” understanding. As Wittgenstein argued in his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, I too argue that confusion often arises not as much from viewpoint differences as regards the substance of the matter, but from the language used to discuss it and our use thereof. While he was referring to philosophical discourse in more general terms, the observation is no less true in the context of social sciences.

2.1. What Is in a Definition?

So, let us start there, with a consideration of what would make a meaningful definition of masculinity. I phrase the question in this constructive form so as to emphasize my intent and focus on the underlying substance, rather than semantics. In so much that a definition merely ‘is’, it cannot be incorrect, nor can it be argued to be wrong in any meaningful sense (to quote Wittgenstein: “In most cases, meaning is use”). However, it is perfectly reasonable, and indeed desirable, to seek such a definition which is useful—useful in delineating phenomena of interest, in facilitating their better understanding, and in providing practically actionable means of addressing social injustices and wrongdoing. In any case, it is important that a common definition is agreed upon before embarking on any further discussion of the concept. What is more, a thoughtful consideration of this issue is important given that the very act of naming a concept brings it into being. As Butler [16] puts it, performativity (the process of creating a concept by acting in a certain way) is “the discursive mode by which ontological effects are installed”.

Thus, my broad goal in the present work is to revisit and discuss the very definition of masculinity as a concept, with a view of arriving at a definition which is sound, clear, and useful in (i) addressing the various relevant forms of harm in society, and (ii) providing a clear conceptual framework for scientific inquiry which would facilitate this change. I start with an examination of the existing work on masculinity which is virtually exclusively in the scientific domain, that is focused on the understanding of the phenomenon masculinity (its aetiology, effects, etc.) as presently defined. This examination allows me to demonstrate the weaknesses of the current definitions and highlight that different authors implicitly adopt different definitions, often without realizing this, thus resulting in much work talking past one another. Illuminated by these insights, I proceed towards my final goal, that is, a new definition which is coherent and which, I contend, would serve better to address the common goals of effecting positive social change.

To expand, right at the start, I would like to preface my argument by explaining what I am and what I am not trying to achieve herein. In particular, I am not arguing that the definition I put forward is the correct one and that those I challenge are in some sense wrong (that is, not those that are internally consistent). Indeed, this would be a meaningless claim, a contradiction in terms, as the central question is that of defining a notion, and a definition in this context cannot be ‘wrong’; it is what we agree it to be. Inverting our labels for what we usually refer to as ‘apples’ and ‘oranges’ would not result in any conflict per se. Rather, it would be a pointless exercise, for there would be no new insight or the potential of one, and nothing substantial would change. Hence, the question at the crux of the debate is what definition would be instrumentally most useful rather than ‘correct’.

2.2. Contemporary Views

Let us begin by observing that masculinity exists only by virtue of its antithesis in the form of femininity. It cannot exist on its own, in a proverbial conceptual vacuum, no more than there can be a hole without a surrounding substance which gives the notion any meaning. This simple realization makes apparent the conceptual errors that result in much of the confusion I emphasised earlier. In particular, in most of the discussion of masculinity, the concept appears merely to be implicitly understood as describing traits exhibited by the male sex. As I already noted, researchers are seldom explicit in stating this, so instead I shall begin with the definition found in Wikipedia (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Masculinity [accessed on 22 August 2023]):

This definition appears sensible enough at first sight, and I expect that most would have no major objections to it. Yet, it does not take much further scrutiny for one to start observing its defects. In particular, note the absence of any, explicit or implicit, recognition of masculinity being a discriminative (n.b. I use this term in a value-neutral fashion) characteristic. For example, bipedality is something that is very strongly associated with men and boys; yet, it is hardly something that anybody would note as a masculine trait. Clearly, the very usefulness of the notion of masculinity, as any other notion, is a consequence of it differentiating phenomena that conform to it and those that do not, in a manner which is useful in some context. Hence, at the very least, the definition should read:“Masculinity (also called manhood or manliness) is a set of attributes, behaviors, and roles associated with men and boys.”

In other words, the notion is inherently relational in nature, and a potentially admissible definition of it must reflect this. I also note here that this does not imply that either of the two notions, masculinity or femininity, are compact and monolithic in nature. Each may very well be further best understood as being comprised of sub-types which themselves stand in relational tension with one another.“Masculinity (also called manhood or manliness) is a set of attributes, behaviors, and roles associated with men and boys but not women and girls.”

Still, this is not the only problematic aspect of the aforementioned definition. Another one concerns the word ‘associated’, which can be variously interpreted. The first interpretation is that which is referred to is perceptual in origin. In other words, the definition can be understood to mean that the notion of masculinity arises from attributes and behaviours, which are seen as being associated with men and boys but not women and girls, regardless of the objective correctness of the said perception. Masculinity understood this way would be ‘in the eye of the beholder’, so to speak. From this, it should not be concluded that such a definition would be trivial in that it would by itself explain masculinity; no, the origin of the said perception would still be a matter of scientific inquiry and permit explanations dependent both on biology (genetics, epigenetics, in utero environment, etc.) or societal factors. Another interpretation of the word ‘associated’ in the given definition, would see it as a claim of an objective association. Though in this case, the notion of masculinity would pertain to an entirely different phenomenon than the one rooted in the subjective, the explication of its origins would again be in the realm of science and still permit an explanation rooted both in the biological and the social.

2.3. Explaining vs. Defining

To emphasise the point I made earlier, little attention has been given to whether the aforementioned definition of the very notion of masculinity is best, that is, whether it is one which is most useful in addressing the various injustices associated with it (e.g., violent behaviour, homophobia, control, the imposition of ‘traditional’ gender roles, etc.). This question is one outside the realm of the scientific; it is a philosophical or ontological question, one informed by material reality and science, but inherently antecedent to any study of masculinity. There has to be a clear understanding of what it is that a notion subsumes before seeking to explain and understand it.

Yet, the existing literature on masculinity either sets off to explain it, without making clear what definition of masculinity is presumed in the inquiry, or mingles the explanation and the definition, effecting a tautological result (though in a convoluted manner, which makes this hidden from obviousness). Thus, Levant [17] writes:

An important thing to note here is that the explanation is not at all admitting of any influence of inherent biological differences between the sexes, but is rather given as a purely social construct. If masculinity is understood as being phenotypic, observable, then, as pointed out by others [18], this explanation thereof will not do—biological constraints and predispositions cannot be ignored. However, the aim of divorcing the two, the biological and the social, has value and will play a significant role in the definition of masculinity that I will advance shortly.“…I see masculinity not as an essential component of men, but as historically situated norms, ideologies, and practices that cultures use to create various meanings of being a man. To the degree that masculinities are restrictive and detrimental to well-being, they need to be pointed out and deconstructed. To the degree that they are adaptive, in particular contexts, they need to be defused from their association with men, and applied more broadly to all people.” [n.b. not the author’s own view, but a quote]

The same views have been voiced by numerous other intellectuals, who also do not offer any clarity on what the nature of the phenomenon they seek to explain is, that is what the definition of masculinity they adopt is. A similar trap is fallen into by those such as Burrell et al. [19]:

who do not attempt to define masculinity themselves, but presume that masculinity is defined in a particular way, failing to recognize what I emphasised earlier, that is, that masculinity is most variously understood both in everyday speech and in the academic literature, and that its definition as used by a particular author is seldom stated explicitly and with clarity. Even more oblivious of this are Konopka et al. [14]:“‘Gender norms’ define the different practices that are expected of women (i.e., what is understood as being ‘feminine’) and of men (i.e., what is seen as being ‘masculine’)”,

whose writing is unclear in whether it is trying to explain masculinity or making a claim regarding its definition, thus achieving neither.“…masculinity is socially constructed…”

In contextualizing the ideas described thus far, it is important to observe the underlying ideological shift which is in part a consequence of different understandings of masculinity as a concept. The change comprises, first, a move away from the definitional to the explanatory, and then from the descriptive (‘is’), to the prescriptive (‘ought’). This is most clearly evident in Burrell’s use of the words “expected of”. I deal with this confounding, famously raised to the fore by Hume [20,21,22], in Section 2.4.

2.3.1. Masculinity as a Social Role

Though different in nature, the problems of defining and then explaining a defined phenomenon necessarily interact. Most obviously, the former sets the stage for the latter. However, it is also the case that an understanding of the world as it is informs us as to what definitions are conducive to the attainment of, say, various social goals, such as justice and fairness, etc. Hence, I would next like to give an overview of two influential frameworks erected for the understanding of muscularity as the concept is presently understood by many. The first of these was developed by Connell [23], and it focuses on the idea of masculinity as a social role.

Connell’s thought has had major impact both on the scholarly treatment of masculinity, as well as in practice, e.g., on the development of policies to reduce domestic violence. She quite rightly rejects one of the dominant ‘mass culture’ views, namely that of biological determinism of men’s behaviour:

“Arguments that masculinity should change often come to grief, not on counter-arguments against reform, but on the belief that men cannot change, so it is futile or even dangerous to try. Mass culture generally assumes there is a fixed, true masculinity beneath the ebb and flow of daily life. We hear of ‘real men’, ‘natural man’, the ‘deep masculine’.”

What is widely seen as one of the key contributions of Connell’s work is the rejection of masculinity as a monolithic concept. Instead, she recognizes multiple masculinities, which are also not fixed or static; rather, they are fluid and dynamic, and they can change over time.

That the focus of Connell’s work is the realm of science, that is to say, is aimed at explaining masculinity rather than at defining the concept itself, is evident from the entire body of her work and illustrated by the following passage [23]:

Though claiming to reject all of the aforementioned:“Two opposing conceptions of the body have dominated discussion of this issue in recent decades. In one, which basically translates the dominant ideology into the language of biological science, the body is a natural machine which produces gender difference—through genetic programming, hormonal difference, or the different role of the sexes in reproduction. In the other approach, which has swept the humanities and social sciences, the body is a more or less neutral surface or landscape on which a social symbolism is imprinted. Reading these arguments as a new version of the old ‘nature vs. nurture controversy, other voices have proposed a common-sense compromise: both biology and social influence combine to produce gender differences in behaviour.”

her view is in the ‘common-sense compromise’ group, to use her own terminology:“…I will argue that all three views are mistaken.”,

“Gender is a way in which social practice is ordered. In gender processes, the everyday conduct of life is organized in relation to a reproductive arena, defined by the bodily structures and processes of human reproduction.” [emphasis added]

More importantly in the context of the present article, here, we can see an example of the confounding of questions of how masculinity is to be defined and what explains its manifestation. This is evident in the words: “Gender is…” (emphasis added). That this is not how gender is widely understood is clearly recognized by the wider context and the tone of Connell’s writing; yet, the wording is that of a claim, one which permits and demands objective confirmation or rejection, which, as explained earlier, is not congruent with an introduction of a definition. As such, we can see that the aforementioned confounding results in the treatment of the notions of gender, masculinity, femininity, and the like, as neo-Platonic concepts which exist in some transcendental form and which human endeavour, philosophical and then scientific, is aimed at apprehending. This is difficult to accept. What is needed first and foremost is a clear definition, one which I argue, is focused on practical goals of utility. As Marx famously said [24]:

“The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point however is to change it.”

In summary, it is important to recognize that my thought does not stand in opposition to Connell’s, for our aims are different. In particular, with a caveat noted previously, Connell’s interest is firmly in the realm of the scientific, that is, she seeks to explain the behaviour of the members of the male sex and takes masculinity simply to refer to this behaviour as well as its socially ‘idealized’ form [23]:

“…research field of men’s studies (also known as masculinity studies and critical studies of men)…” [emphasis added]

“Discursive studies suggest that men are not permanently committed to a particular pattern of masculinity.”

“Consequently, ‘masculinity’ represents not a certain type of man but, rather, a way that men position themselves through discursive practices.” [emphasis added]

As I have already stated, there is absolutely nothing inherently wrong with the acceptance of this understanding of masculinity, and the goal of understanding men’s behaviour is undoubtedly worthwhile, intellectually and practically. That being said, and with a reference to the positioning of the present work stated in the introduction, in that my effort here is to argue for the adoption of an alternative definition of the very notion of masculinity, my thought should not be considered as standing against Connell’s; rather, the two can be seen as complementary. Indeed, this is why a brief discussion of Connell’s work is useful as an interlude to my contribution.

2.3.2. Masculinity as Performance

The differences between the objectives of my work herein and those of Connell are similar to those which can be recognized when the former is contrasted with the writings of Butler [16], another notable contributor to the discussion. Butler’s analysis, much like Connell’s, has greatly contributed to the erection of a framework for the examination and critique of masculinity as the notion is presently understood. Like Connell, Butler too recognizes the non-monolithic nature of the present-day notion of masculinity, as well as its manifestation across different levels of social organization, from intimate and personal, to macroscopic and political. A key notion in her work is that of ‘performativity’, that is, the ways in which socially constructed masculine norms are repeated and reproduced through everyday behaviours. Through behaviour, Butler argues (and I agree) that we are both expressing our identity within a complex social milieu, with a possibility both of conforming to the expectations of a particular society as well as of challenging these; the result, just as recognized by Connell, is an ever-changing social construction of what masculinity is, and, hence what it should be. In this, Butler’s work too serves to underline the motivation and premise of my work, which is that a normative definition of the notion cannot be divorced from a prescriptive element, thereby through its heteronomy limiting the self-actualization of an individual. In that respect, the present work can be seen as advancing Butler’s stated aim [25], namely that:

by challenging the very essence of the present-day use of the word ‘masculinity’ and freeing it from social imposition, allowing the individual truly to pursue Sartre’s ‘authenticity’ [26] “by recognizing ourselves as the author” of the meaning of our actions. This would allow us to study emergent behaviour in a far less toxic manner (noting that the abolition of values in scientific inquiry is neither possible nor desirable [27,28]) and move away from a polemic discourse on masculinity vs femininity, towards a constructive re-examination of the values that bind us as a society.“The task is not to essentialize gender, but to locate the possibility of agency within the very practices that create the illusion of an essential self.”,

While consonant with Connell’s and Butler’s ideas, the present proposal also directly addresses a valid criticism of these authors’ works, namely that in the focus on the proximal—that is, social—factors shaping the present-day notion of masculinity, their distal causes—that is, those residing in biology—are excessively sidelined. Yet, these are crucial in understanding the origins of social phenomena, as well as the constraints of the same, and are hence instrumental in guiding decisions aimed at effecting positive change. Wood and Eagly [29] express this well:

“When psychologists have addressed this causal question, they have primarily considered the immediate, proximal causes for sex-differentiated behavior, such as gender roles and socialization experiences. Many psychological theories of sex differences have been silent with respect to ultimate, distal causes such as biological processes, genetic factors, and features of social structures and local ecologies.

Social behaviours and structures do not emerge out of nothingness and arbitrarily. While there is no doubt that they are subject to a host of external, circumstantial forces, these can only affect the trajectory of social phenomena within the space shaped and limited by the underlying biology from which any behaviour must emerge.To produce adequate explanations of sex differences, psychologists need to relate the proximal causes of psychological theories not only to predicted behaviors and other outcomes but also to the distal causes from which these proximal causes emerge. Understanding the distal causes of sex differences constrains psychological theorizing to the extent that it enhances the plausibility of some proximal causes and diminishes the plausibility of others.”

2.4. Normative Expectations

When Burrell et al. [19], Connell [23], and others talk about the expectations placed on individuals of a particular sex, by this, they refer to normative societal pressures [14]. In that any expectation of this nature is restrictive on the individual by its very character, to root any discussion thereof necessitates that we start from the grounding point of ethics, that is, Schopenhauer’s ‘why’ “of virtue, the ground of that obligation or recommendation or approbation” [30]. Indeed, like Schopenhauer and many since him, such as Kierkegaard and Dostoevsky, I too start from the principle that the basis of morality, its essence, should be sought in sympathy [31], which ultimately rests on sentience, that is, the recognition of others’ ability to experience pleasure on the one hand and suffering on the other [32]. In the context of the present discussion, an important condition for allowing minds endowed with self-consciousness to pursue happiness and pleasure is individual autonomy [33], that is, the freedom from arbitrary restrictions in one’s decision making, which is well supported by empirical evidence [34,35,36]. In that contemporary liberal values place an individual’s autonomy over their choices at the heart of ethics [37,38], I believe that I am on safe ground in stating that no expectation should be placed on any person purely based on their sex, an expectation which would indeed impose an arbitrary and needless restriction in how one leads their life. In that, I agree with the broad point made by Levant [17] that behaviours which are

and that those that are“restrictive and detrimental to well-being …need to be pointed out and deconstructed”,

“adaptive, in particular contexts, …need to be defused from their association…and applied more broadly to all…”

What the reader will notice is that in the quotes above, I have removed any specific reference to masculinity, and instead refer to behaviours in general and without any further qualification, thereby divorcing the association of the concept of masculinity from a prescriptive imperative.

For completeness, I would also like to note my disagreement with Levant’s reference to adaptive behaviour. As discussed in previous work [32], behaviours which are adaptive from the point of the agent engaged in those behaviours may in fact be ethically objectionable, even grotesquely so [30]; rape [39], incest [40], murder [41], and theft [42] are just some readily evident examples. Thus, it is not the adaptive nature that should be a motive for advocating and promoting a particular behaviour, but rather its positive moral substance. In so much that there is a conflation of that which is moral and that which is rational and adaptive, the error committed here is not unlike that of Kant, who tried to seek the foundation of morals in universal duties emanating from reason alone [43]. The alternative advanced by Schopenhauer [30], following his rebuttal of Kant, that:

is far more convincing (n.b. I am mostly, but not fully, in agreement with Schopenhauer as regards this stance).“…the intention alone decides on the worth or unworth of the deed, which is why the same deed, according to its intention, can be reprehensible or praiseworthy.”

That the understanding of masculinity as a descriptive rather than a prescriptive notion is an idea which is far from foreign or objectionable, even to the general public, is evidenced by the dramatic weakening of sex-based norms in the secular world in recent history [44]. Pressures on women (as well as men) to dress in a particular manner on a day-to-day basis have tremendously declined [45], and at least some of the remaining pressures (e.g., in specific professions) have an instrumental rather than a fundamentally sexist character [46,47]; the erstwhile unthinkable [48] women’s assumption of leadership roles, both in society and in the workplace, has not only become commonplace but an expectation [49,50], etc.

2.5. Masculinity Disentangled

My aim is to disentangle the descriptive from the prescriptive, and the dispositional from the socially constructed, and to show how an understanding of masculinity within this framework offers actionable means constructive in the pursuit of the golden rule of ethics, namely, “Harm no one; rather help everyone to the extent that you can.” [30]. In that any sex-based prescription would be arbitrarily restrictive to one’s agency, freedom, and the pursuit of happiness, I argue that masculinity (and with it, femininity too) should be defined in a purely objective sense, as a dispositional characteristic discriminating the biologically male sex from the biologically female on the population level. Lest my point be misunderstood, I stress again that I am talking about population level differences, i.e., the claim is inherently about the distributions of characteristics over the populations, which does not mean that even on a descriptive level, the difference is present for every individual—the distributions can significantly overlap (and in many cases do [18]), exhibit multi-modality, etc. Furthermore, the qualification by dispositionality implies that what such ontologically reconstructed masculinity is cannot be inferred by crude observational means, for any materialized characteristic is contingent on the environment, that is, it is a product both of predispositions towards the characteristic and the social environment which encourages and fosters, or inhibits and represses it, as correctly pointed out by Fine et al. [18] amongst others. Hence, masculinity re-defined in the manner I suggest can be understood as being characterized not by specific traits and behaviours as such, but rather predispositions towards the same.

It is important to note that the proposed change of definition is respectful of the notion’s historical use, in that it retains an essence which is common to all, implicit or explicit, understandings of masculinity to date—namely, that it is something to do with men—which is key to the possibility of its adoption in practice, while at the same time eliminating even the very possibility of appearing masculine, since the notion no longer describes an observable trait. No longer can one try to appear masculine or be subject to such pressure, since masculinity refers to something latent as opposed to phenotypic. Thereby, this change shifts focus onto freely made, reason- and compassion-driven choices rooted in morality.

Going back to the powerful explanatory framework erected by Connell and Butler, the notions such as gender and masculinity (lest there be confusion, note that the contemporary concept of masculinity is different than that of both sex and gender—a biologically female person, say, who also identifies as a woman, can be characterized as being more or less masculine, whatever the performative reality of a certain society may be), are in large part performative in nature, and as such, malleable by the society. There is also much to be objected to regarding what this performativity entails at present. But let us suppose that the performative landscape is successfully altered, which many see as the avenue for social betterment (c.f. the aforementioned calls for ‘gentler masculinity’). Certain performative aspects are certainly morally significant and unacceptable, e.g., non-defensive violent behaviour. The aim of those advocating for a social re-shaping of masculinity is then to dissolve these, and quite rightly so. If this is achieved, then they cease to be characteristics of masculinity. Let us now suppose that the efforts of dissolving all such morally objectionable traits (both on the side of masculinity and its associated opposite, femininity) of masculinity are successful (by making it ‘gentler’, etc.). Then, the only remaining defining, performative traits must be amoral in nature. At this point, whatever the performativity of the concept ends up entailing, even if it is seen in a purely descriptive fashion, by virtue of one’s comparison of their self with any performative standard, the person is socially pressured to comply. But how can that be right given the amoral nature of the performative nature of the phenomenon? Of course, one may choose not to comply, but at the cost of unnecessary trauma. I say ‘unnecessary’ because there is no ethical dimension to such compliance and pressure; as long as something is morally acceptable, the individual should be allowed to pursue it freely. A deviation from the socially constructed norms, whatever we make them be, is pressure-inducing. The logical conclusion is that of an ultimate dissolution of the very concepts of masculinity and femininity. While I find this desirable, given my contention that an individual should be free of dictatorial social norms, it is in this conclusion that the idea of the advocated gradual change of masculinity falls on itself: it is fantastical to believe that a concept can be dissolved by means of a social process which constantly reinforces the existence of the concept through a focus on the concept itself. Instead, my proposal can be seen as de facto achieving the same goal by recognizing that the way of escaping the “ought” is to divorce the notion from the observable and performative traits altogether. It is an ultimate liberating act.

2.6. Subjective Desirability

Having rejected any prescriptive content in the notions of masculinity and femininity, and with it, any duty or obligation that an individual of a particular sex should feel in matching the predispositions characterizing that sex on the group level, I would now like to turn my attention to the inherent material, that is, practical constraints of a free individual’s choices or indeed the unchosen sex atypical traits they exhibit. As I detailed previously, my aforementioned rejection of prescriptiveness in this context was erected on basic moral arguments, and the widely recognized principles of individual autonomy and freedom [33]. However, this does not imply that an individual’s behaviour is free in the sense that their freely made choices are void of potentially undesirable consequences in the world as it is, even if incidental societal norms were to disappear.

For illustrative purposes, herein, I will consider one clear example, namely that of sexual attractiveness. That sexual attractiveness is affected by culture is beyond any debate: a look at the ideals of beauty in art over time [51] or indeed those reflected in cosmetic medicine [52] readily shows this to be the case. Equally indubitable are the biologically driven preferences which are maintained across cultures [53,54]. Considering the central role that procreation plays in the selection of behavioural and physical traits, this can hardly come as a surprise [55]. It is no more surprising that these behavioural and physical traits differ between the two sexes for, as elucidated by Dawkins [56] with admirable clarity, the co-evolution of the sexes is characterized both by their partial alignment in interests, and thus, cooperation, and by the partial divergence of of their interests, and thus, competition [57]. These preferences are intrinsically amoral in nature; yet, they have a profound effect on people’s life experiences. For example, sexual attractiveness strongly influences one’s choice of a romantic mate and plays a crucial role in romantic relationships [58,59], and these relationships are, quite expectedly for all the reasons highlighted already, instrumental in individuals’ feelings of happiness and well-being [60,61,62,63]. Consequently, any individual whose traits deviate sufficiently from those which the opposite sex has evolved to prefer and which, as such, contribute to the stereotypes of their own sex, will encounter difficulties in the pursuit of romantic fulfilment, even if simply by virtue of reduced potential partner availability and interest. As the analysis of Thornhill and Gangestad [64] finds:

A statement of this fact is by no means an implicit prescription either to behave or to modify one’s appearance in a certain way; it is merely an important recognition of the complexity of the material world as it is, and of the balancing act that individual freedom and autonomy must manage in the weighing of the different preferences which pull one’s decision making in divergent directions.“Adaptationists have examined a number of hypotheses subsumed under the general notion that facial-attractiveness judgments serve to discriminate an individual’s phenotypic condition and, broadly speaking, health status. This review has suggested that these areas of research have been fruitful. Some areas have found considerable support for particular hypotheses (e.g., that facial symmetry increases attractiveness and an average face is attractive, even if not the most attractive). Other areas have led researchers to identify interesting patterns of preferences that are more complex than was initially anticipated (e.g., that women’s preference for masculine features is not unconditional but rather shifts with women’s cycle-based fertility and that, generally, slightly feminine male faces are actually preferred).”

2.7. Effecting Change

Before concluding the article, I would like to return briefly to the increasingly prominent advocation for social change in the form of a “gentler masculinity” [65,66,67,68]. Well meaning as this initiative may be, and I do not doubt the beneficency of the motives underlying it, I trust that its fundamental philosophical flaws are readily apparent from the the critical analysis I laid out in the present article. As I emphasised right at the start of the discussion, like most of the authors whose work concerns masculinity, those calling for a gentler form thereof fail to give the notion due consideration, leaving it insufficiently clearly defined and confounded by prescriptive notions. If masculinity is understood as I proposed, then any calls for a change to it cease to make sense, for the concept is fundamentally latent and unalterable. As such, this understanding transforms the conceptualization of one’s identity away from what is inherently amoral in nature, focusing on the true crux of the problem which is that of acting in accordance with the Golden Rule of ethics, that is, simply, treating others kindly.

In short, if masculinity is understood in a principled and coherent manner, attempts at change should not be directed towards the specific content thereof, but rather towards the moral substance of behaviour, which ought to be wholly independent of one’s masculinity.

3. Conclusions

The concept of masculinity, and to a lesser extent, that of femininity, often seen as its antithesis, continues to attract an increasing amount of attention, both in mainstream social discourse and in published academic work. While the spirit of the former is getting ever more vehement, divisive, and unconstructive, the latter appears impotent in effecting a conciliatory resolution. In this article, I argued that there are several reasons for this ineffectualness.

Firstly, I highlighted the dire lack of inquiry into the foundation underlying the very notion of masculinity, that is, its definition which must precede any attempt at explaining its phenomenology, resulting in a great volume of work contingent on unstated and poorly conceived premises. In a sense, this is a semantic inquiry. However, I explain that it is important to appreciate that this is no mere semantic quibbling, but rather, that our semantic choices have profound and long-reaching philosophical, instrumental, and ethical consequences. Hence, I frame the task of formulating the best definition of masculinity in reference to real-world goals: the aim is to formulate a definition which serves best both to provide a backdrop for the reinforcement of morally good behaviour and the suppression of morally objectionable actions, as well as to guide scientific inquiry while removing from it the burden of stifling social connotations. Secondly, with reference to influential work on the explanations of masculinity, a task separate from that undertaken by myself, I show how present-day understandings of masculinity fail to serve best that purpose. My analysis elucidated the conflation of the descriptive and the prescriptive, which I criticized on the basis that it transgresses the very foundations upon which contemporary ethics stands.

Hence, I proposed a different conception of masculinity, understood in a purely objective sense, as a dispositional characteristic discriminating the biologically male sex from the biologically female on the population level, and as such characterized not by specific traits and behaviours, but rather by predispositions. Considering that the proposed understanding is empirical in nature, albeit so in a nuanced manner, I also presented a rebuttal of the previously expressed objections to empirical definitions of masculinity, objections which were misled by poorly conceived empiricism rather than empiricism per se.

What is appealing about the definition that I propose is that it inherently eliminates the very possibility of appearing masculine through, say, violence, since masculinity is no longer something that is an observable trait, be it behavioural or otherwise. No longer can one try to appear masculine, since masculinity refers to something latent. And it is not only that an attempt at masculine behaviour, the idea of ‘masculine behaviour’ being rendered a meaningless construct, is eliminated, but there is also an opening to the appreciation of cognitively driven, positive behaviour which combats any negative biological predispositions—the focus is shifted away from ill-founded biological determinism to the morality of our conscious choices, which, through behaviours which are generally virtuous (in Aristotelian sense), such as perseverance, temperance, etc., overcome any morally objectionable or otherwise harmful biology (much like in the case of racism, which I noted earlier). This changes the semantic landscape of the related scientific inquiry, removing the burden of so-called ‘baggage concepts’ [69]. Thus, the change I advocate does not diminish the need to study and to seek to understand the aetiology of violence in a specific context and to examine which environmental (in the widest sense) factors serve to encourage it and which to suppress it. In turn, I discussed a range of practical consequences of the adoption of the proposed definition, and demonstrated its constructive and actionable nature in the real world.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Saylo, M.C.; Escoton, C.C.; Saylo, M.M. Punctuated equilibrium vs. phyletic gradualism. Int. J. Bio-Sci. Bio-Technol. 2011, 3, 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Boto, L.; Martínez, J.L. Ecological and temporal constraints in the evolution of bacterial genomes. Genes 2011, 2, 804–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernat, M. Gender stereotypes and the relationship between masculinity and femininity: A developmental analysis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 61, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. Autonomy and Social Relationships: Rethinking the Feminist Critique. In Feminists Rethink the Self; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 40–61. [Google Scholar]

- Garlick, S. The Nature of Masculinity: Critical Theory, New Materialisms, and Technologies of Embodiment; UBC Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, C. What is “toxic masculinity” and why does it matter? Men Masculinities 2021, 24, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupers, T.A. Toxic masculinity as a barrier to mental health treatment in prison. J. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 61, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, K. Challenging toxic masculinity in schools and society. Horizon 2018, 26, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krahé, B. Gendered self-concept and the aggressive expression of driving anger: Positive femininity buffers negative masculinity. Sex Roles 2018, 79, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K. Violence against women: State responsibilities in international human rights law to address Harmful ‘Masculinities’. Neth. Q. Hum. Rights 2008, 26, 173–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, M. What is hegemonic masculinity? Theory Soc. 1993, 22, 643–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C. Marginalized masculinities and hegemonic masculinity: An introduction. J. Men’s Stud. 1999, 7, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, J.T. Concepts of Masculinity. Psychol. Gend. 1985, 32, 59. [Google Scholar]

- Konopka, K.; Rajchert, J.; Dominiak-Kochanek, M.; Roszak, J. The role of masculinity threat in homonegativity and transphobia. J. Homosex. 2021, 68, 802–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, C. Theories of masculinity. BMJ 1998, 317, 1072–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, J. Gender as performance. In A Critical Sense; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 109–125. [Google Scholar]

- Levant, R.F. How do we understand masculinity? An editorial. Psychol. Men Masculinity 2008, 9, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, C.; Jordan-Young, R.; Kaiser, A.; Rippon, G. Plasticity, plasticity, plasticity…and the rigid problem of sex. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2013, 17, 550–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burrell, S.; Ruxton, S.; Westmarland, N. Changing Gender Norms: Engaging with Men and Boys; Technical Report; Government Equalities Office: London, UK, 2019.

- Hume, D.; Selby-Bigge, L. A Treatise of Human Nature; The Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1789; 3 Volumes. [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre, A.C. Hume on ‘Is’ and ‘Ought’; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, G. Hume on is and ought. Philosophy 1962, 37, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, R.W. Masculinities; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, W.M. Karl Marx’s Verse of 1836–1837 as a Foreshadowing of his Early Philosophy. J. Hist. Ideas 1967, 28, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Butler, J. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Indentity; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sartre, J.P. Being and nothingness. In Central Works of Philosophy v4: Twentieth Century: Moore to Popper; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 4, p. 155. [Google Scholar]

- Dupre, J.; Kincaid, H.; Wylie, A.; Douglas, H. Rejecting the ideal of value-free science. In Value-Free Science? Ideals and Illusions; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lacey, H. Is Science Value Free?: Values and Scientific Understanding; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, W.; Eagly, A.H. A cross-cultural analysis of the behavior of women and men: Implications for the origins of sex differences. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schopenhauer, A. The Two Fundamental Problems of Ethics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright, D.E. Kant, Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche on the morality of pity. J. Hist. Ideas 1984, 45, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arandjelović, O. On the Value of Life. Int. J. Appl. Philos. 2022, 35, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegel, G.W.F.; Inwood, M. Hegel: Philosophy of Mind: Translated with Introduction and Commentary; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Haworth, L. Autonomy and utility. Ethics 1984, 95, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirkov, V.I.; Sheldon, K.M.; Ryan, R.M. Introduction: The struggle for happiness and autonomy in cultural and personal contexts: An overview. In Human Autonomy in Cross-Cultural Context; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chekola, M. Happiness, rationality, autonomy and the good life. J. Happiness Stud. 2007, 8, 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varelius, J. The value of autonomy in medical ethics. Med. Health Care Philos. 2006, 9, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, M. Feminism in ethics: Conceptions of autonomy. In The Cambridge Companion to Feminism in Philosophy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; pp. 205–224. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, J.; Vaughan, A.E. Evolutionary theories of rape. Psychol. Evol. Gend. 2001, 3, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinker, S. The Blank Slate; Southern Utah University: Cedar City, UT, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlén, M.; Söderlund, M. The homicidol effect: Investigating murder as a fitness signal. J. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 152, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Buck, A.; Pauwels, L.J. Intentions to Steal and the Commitment Problem. The Role of Moral Emotions and Self-Serving Justifications. Evol. Psychol. 2022, 20, 14747049221125105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, I.; Schneewind, J.B. Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Boudet, A.M.M.; Petesch, P.; Turk, C. On Norms and Agency: Conversations about Gender Equality with Women and Men in 20 Countries; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Glascock, J. Gender roles on prime-time network television: Demographics and behaviors. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2001, 45, 656–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitidou, Z.; Gasouka, M. Construction of gender through fashion and dressing. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2013, 4, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arandjelović, O. The making of a discriminatory ism. Equal. Divers. Incl. 2023, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, D.D. Victorian feminism and the nineteenth-century novel. Women’s Stud. Interdiscip. J. 1972, 1, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nmark, F.L. Women, leadership, and empowerment. Psychol. Women Q. 1993, 17, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C. Stereotyping and women’s roles in leadership positions. Ind. Commer. Train. 2014, 46, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creekmore, A.M.; Pedersen, E. Body proportions of fashion illustrations, 1840–1940, compared with the Greek ideal of female beauty. Home Econ. Res. J. 1979, 7, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oumeish, O.Y. The cultural and philosophical concepts of cosmetics in beauty and art through the medical history of mankind. Clin. Dermatol. 2001, 19, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.; Brace, C.L.; Jankowiak, W.; Laland, K.N.; Musselman, L.E.; Langlois, J.H.; Roggman, L.A.; Pérusse, D.; Schweder, B.; Symons, D. Sexual selection, physical attractiveness, and facial neoteny: Cross-cultural evidence and implications [and comments and reply]. Curr. Anthropol. 1995, 36, 723–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D. Female mate value at a glance: Relationship of waist-to-hip ratio to health, fecundity and attractiveness. Neuroendocrinol. Lett. 2002, 23, 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwallis, C.K.; Uller, T. Towards an evolutionary ecology of sexual traits. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010, 25, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, R. The Extended Phenotype: The Long Reach of the Gene; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wiley, R.H.; Poston, J. Perspective: Indirect mate choice, competition for mates, and coevolution of the sexes. Evolution 1996, 50, 1371–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Young, R.K. Body weight, waist-to-hip ratio, breasts, and hips: Role in judgments of female attractiveness and desirability for relationships. Ethol. Sociobiol. 1995, 16, 483–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D. Mating strategies of young women: Role of physical attractiveness. J. Sex Res. 2004, 41, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A. Setting goals for life and happiness. Handb. Posit. Psychol. 2002, 522, 299–312. [Google Scholar]

- Demir, M. Sweetheart, you really make me happy: Romantic relationship quality and personality as predictors of happiness among emerging adults. J. Happiness Stud. 2008, 9, 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arandjelović, O. On the subjective value of life. Philosophies 2023, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, M. Close relationships and happiness among emerging adults. J. Happiness Stud. 2010, 11, 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornhill, R.; Gangestad, S.W. Facial attractiveness. Trends Cogn. Sci. 1999, 3, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A. Postfeminist Men’s Movements: The Campaign Against Living Miserably and Male Suicide as ‘Crisis’. In The New Politics of Fatherhood; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 165–191. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, B.A. Trans Manhood: The Intersections of Masculinities, Queerness, and the South. Men Masculinities 2022, 25, 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, L. Chameleon masculinity: Developing the British ‘population-centred’soldier. Crit. Mil. Stud. 2016, 2, 84–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nye, R.A. Locating masculinity: Some recent work on men. Signs J. Women Cult. Soc. 2005, 30, 1937–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groom, A.; Webb, K. Injustice, empowerment, and facilitation in conflict. Int. Interact. 1987, 13, 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).