“Just lmk When You Want to Have Sex”: An Exploratory–Descriptive Qualitative Analysis of Sexting in Emerging Adult Couples

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Communication in Relationships

1.2. Sexual Communication in Relationships and Technology

1.3. Current Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Data Analysis Plan

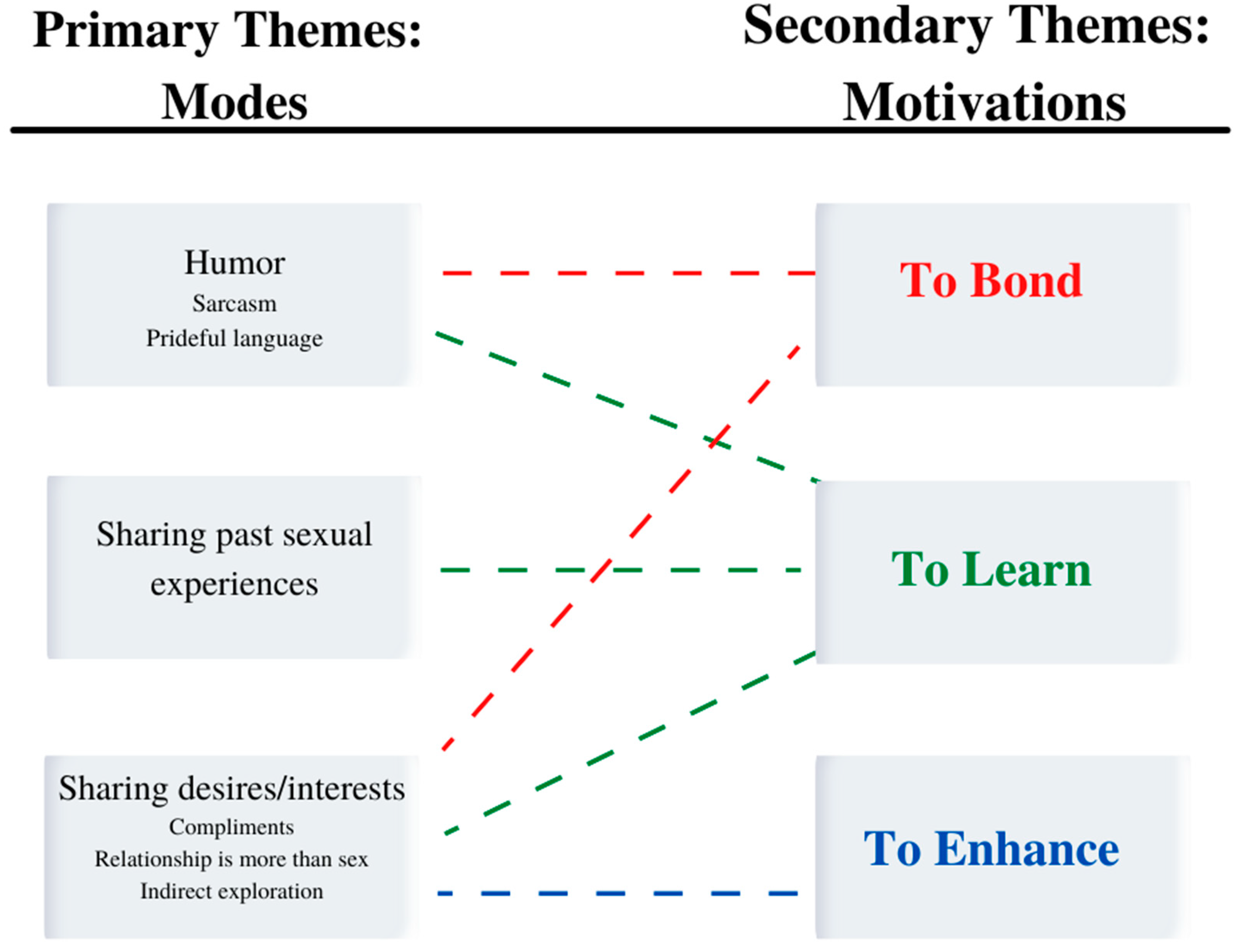

3. Results

3.1. To Bond

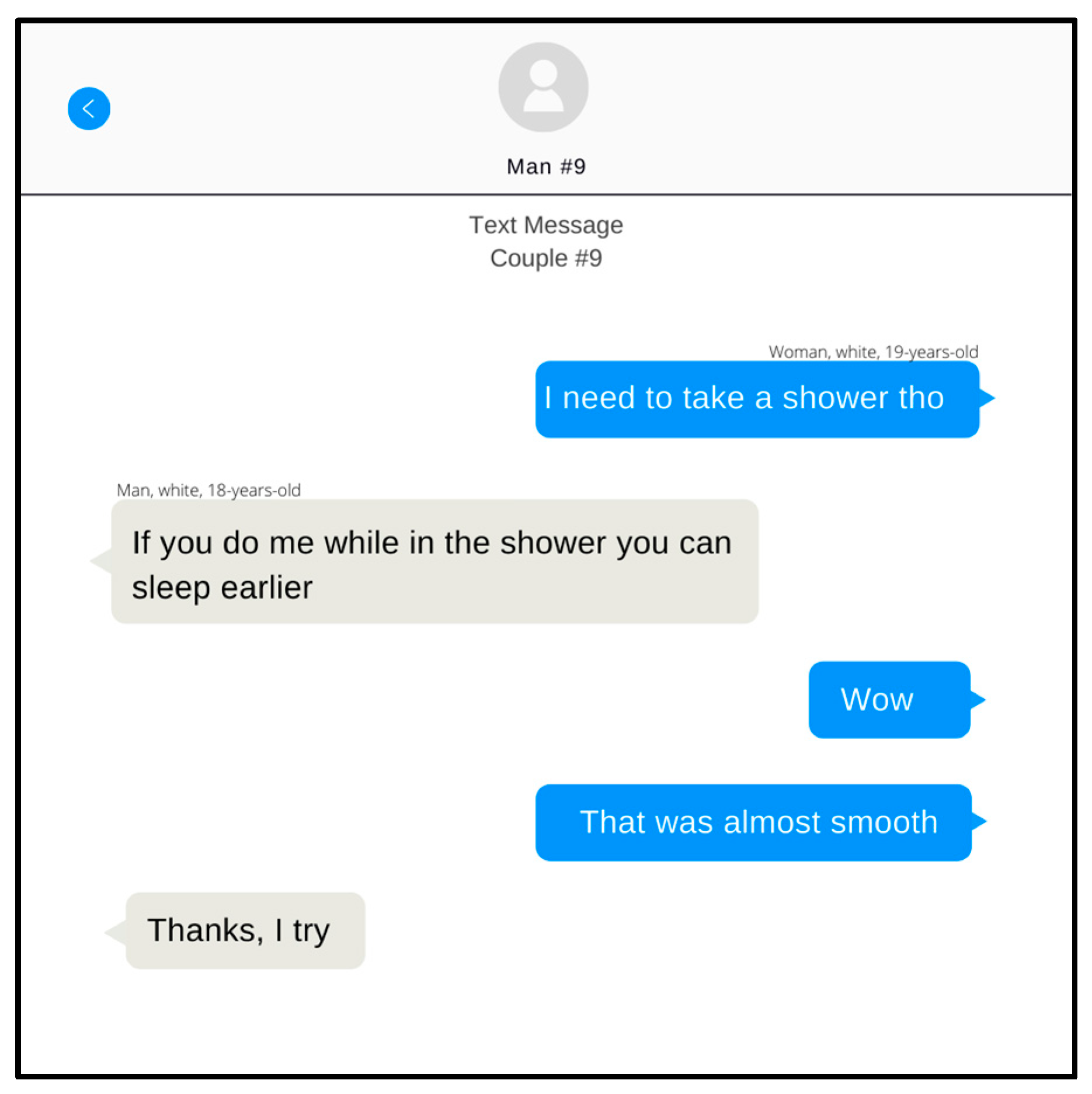

3.1.1. Humor

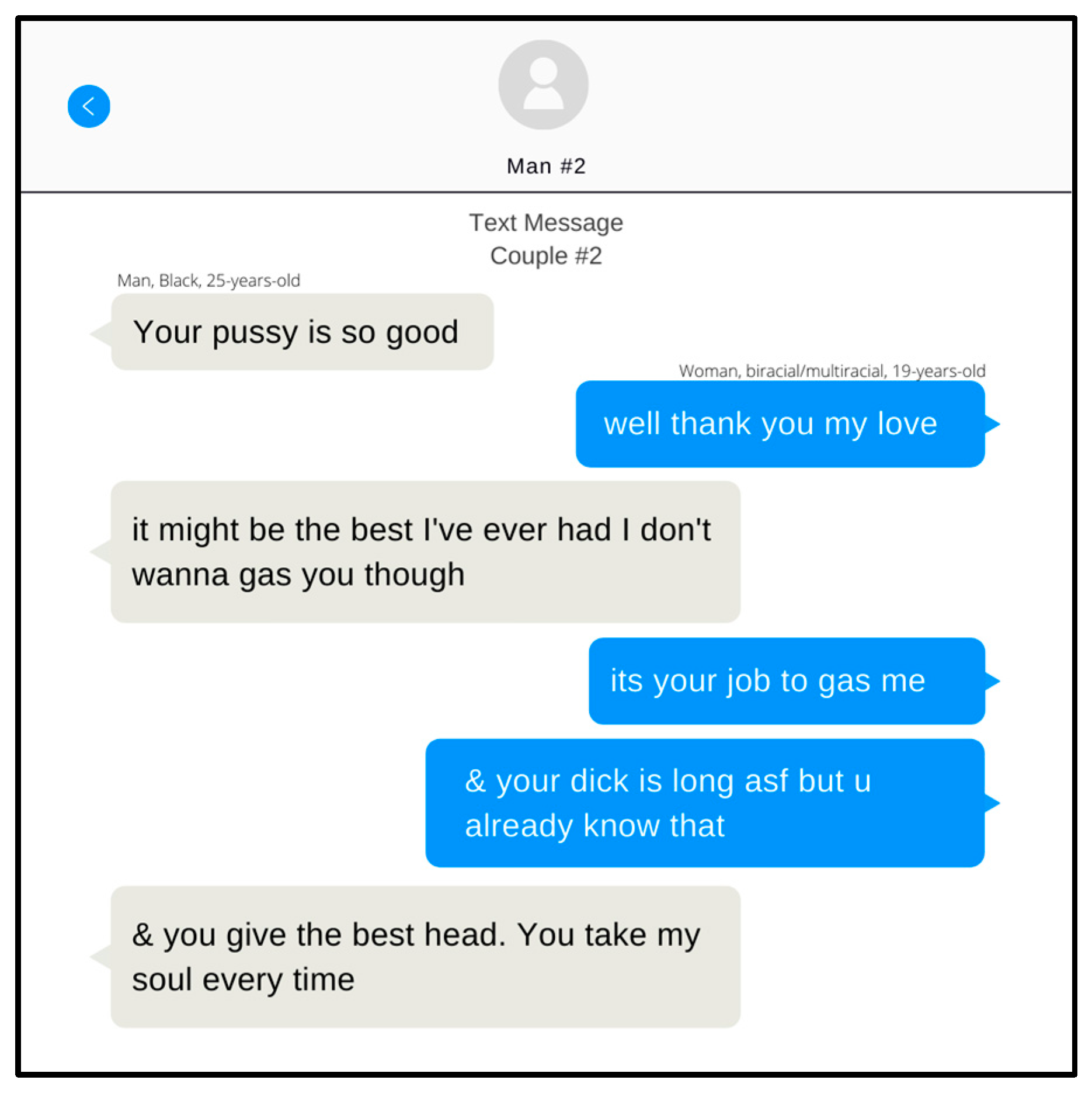

3.1.2. Using Compliments

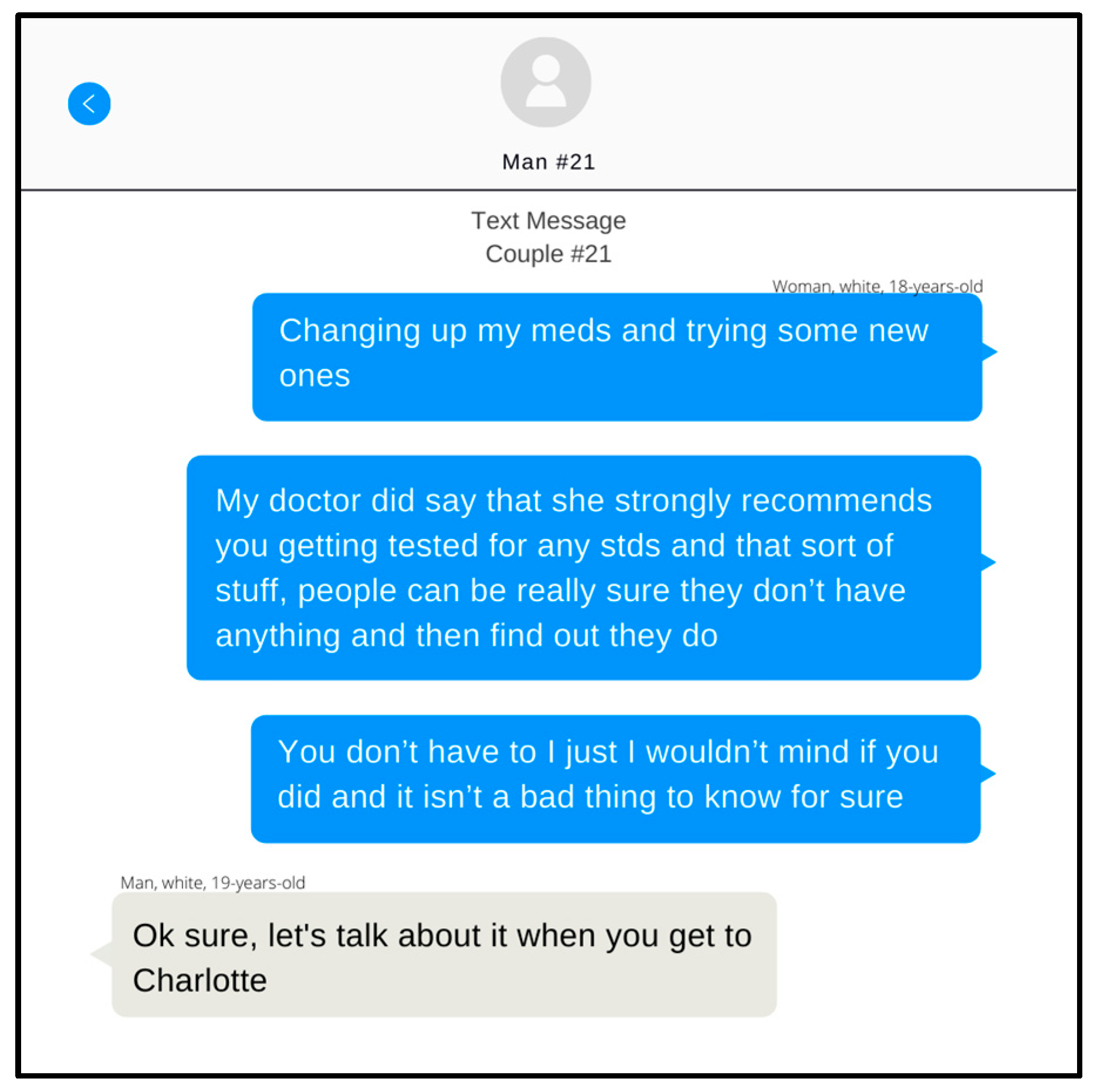

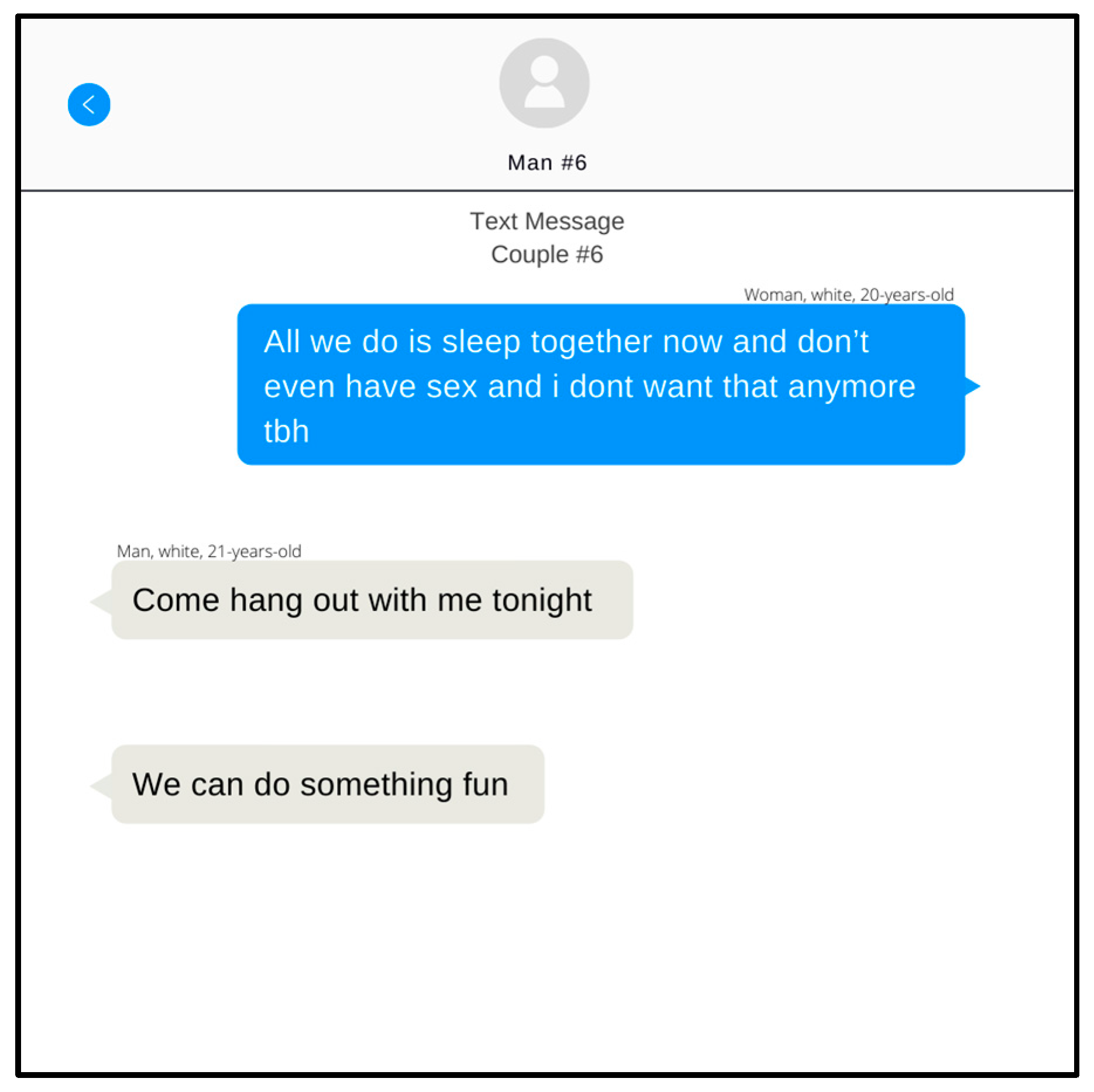

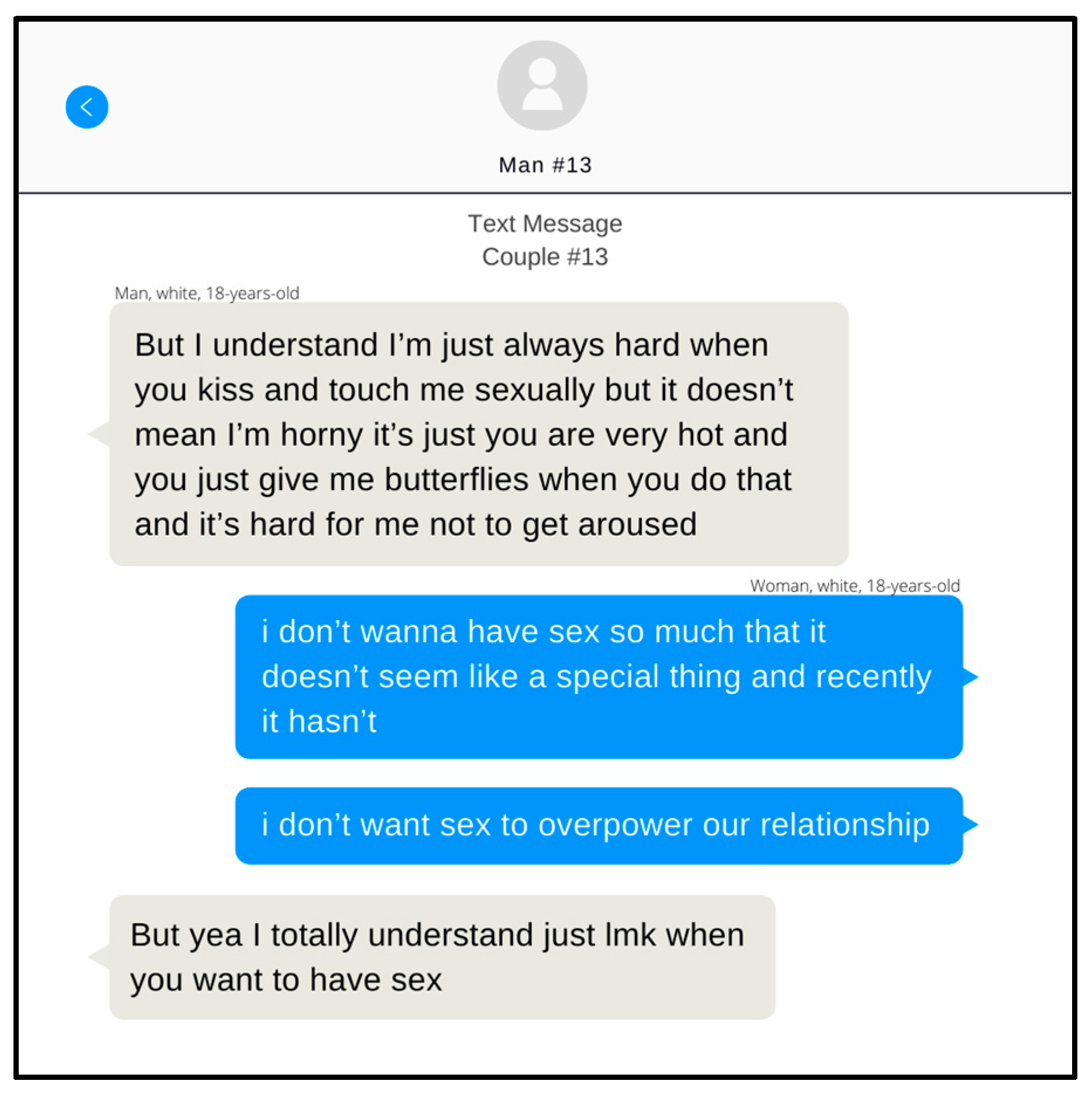

3.1.3. Relationship Is More Than Just Sex

3.2. To Learn

3.2.1. Humor

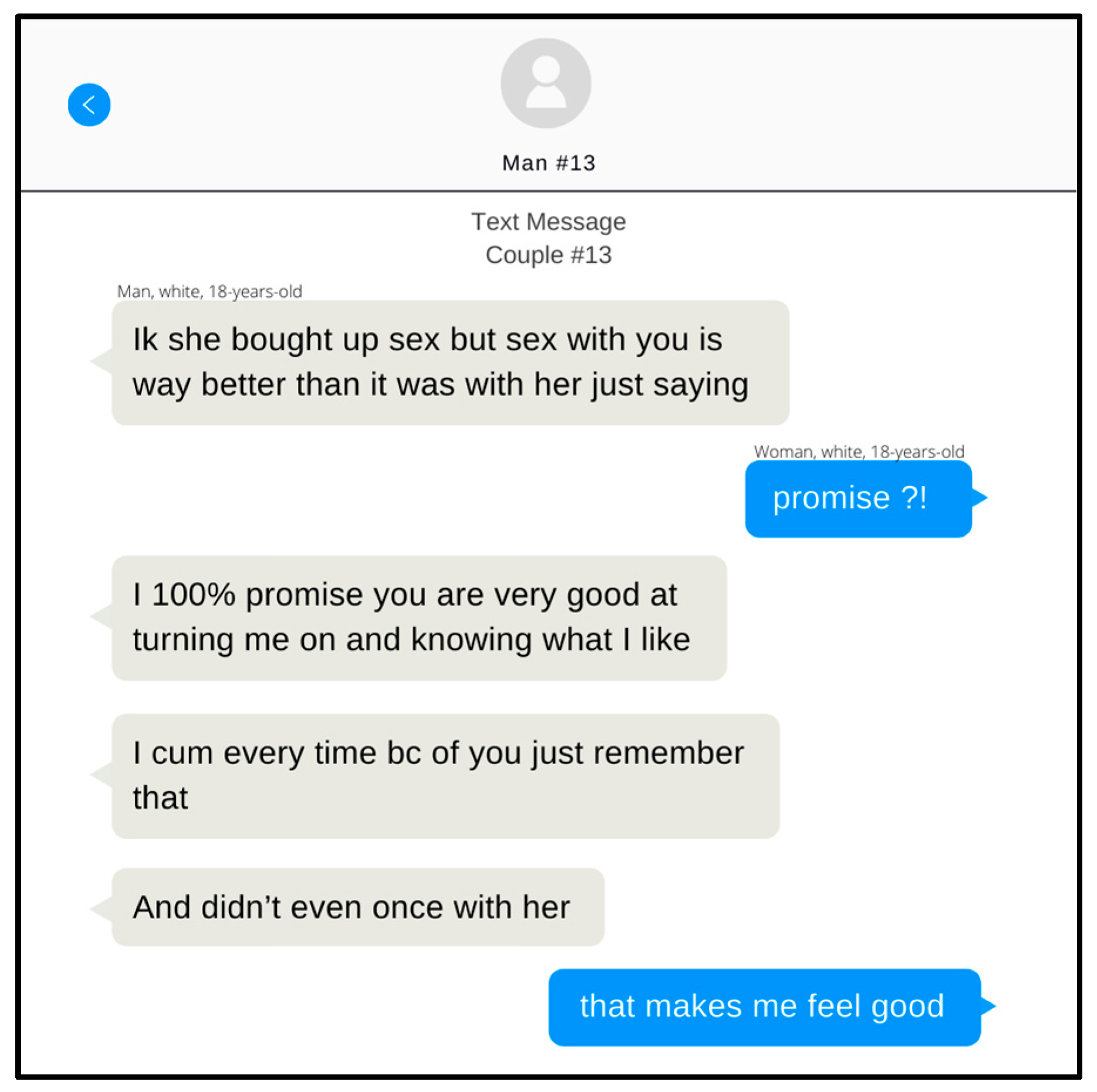

3.2.2. Exploring Past Sexual Experiences/Partners

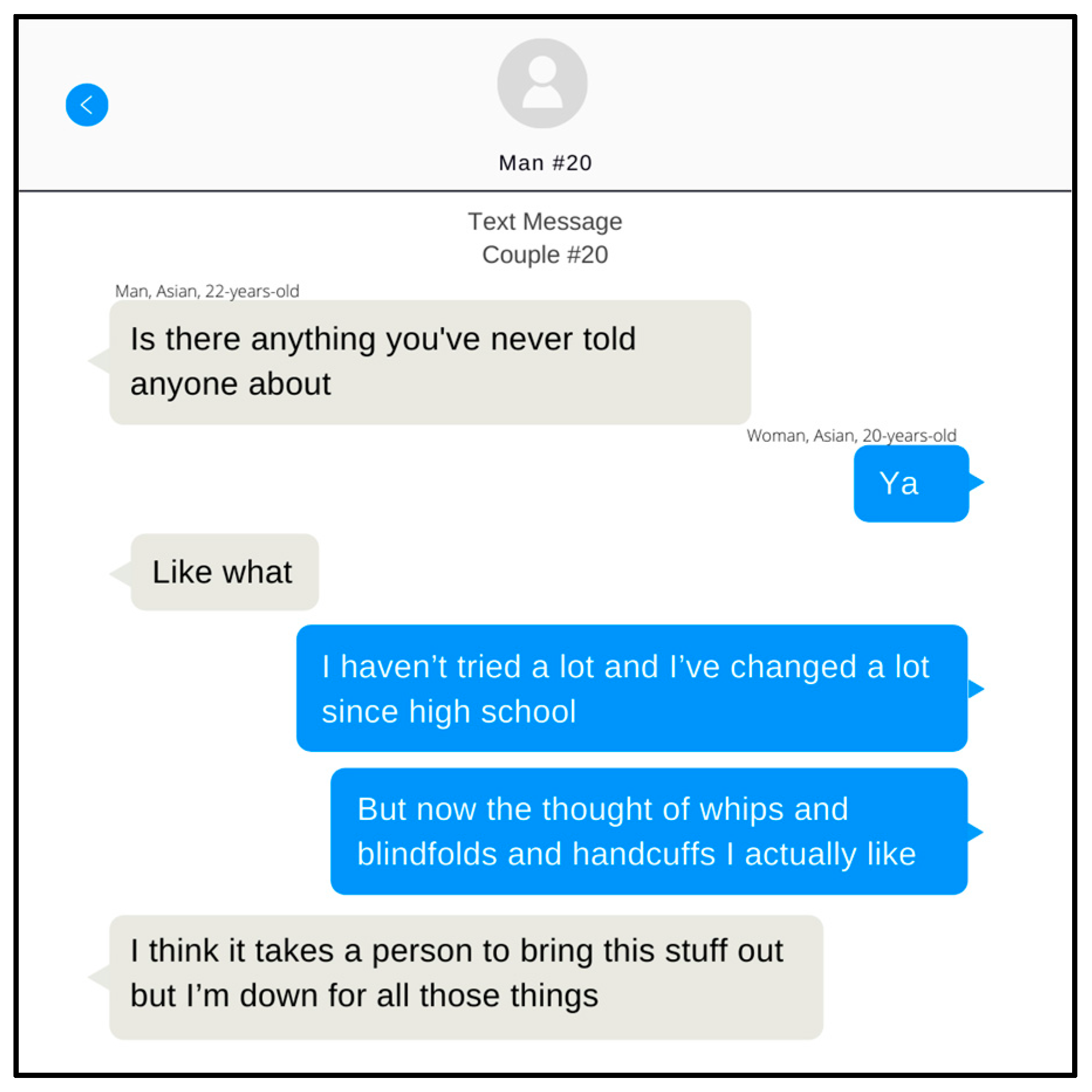

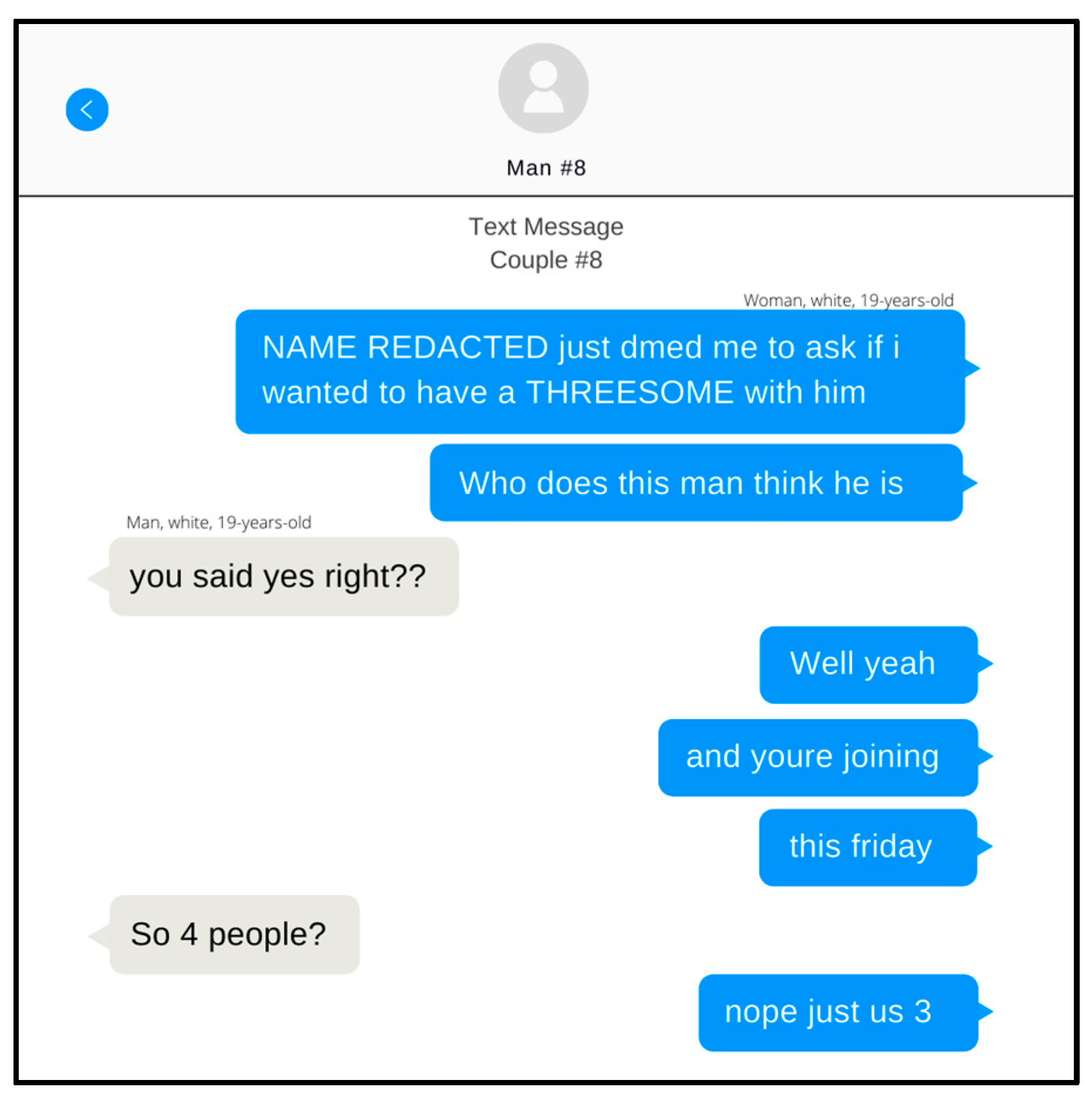

3.2.3. Exploring Sexual Interests

3.2.4. Indirect Sexual Exploration

3.3. To Enhance

3.3.1. Desires for Future Sex (Quality/Quantity)

3.3.2. Compliments

3.3.3. Relationship Is More Than Just Sex

4. Discussion

4.1. To Bond

4.2. To Learn

4.3. To Enhance

5. Limitations and Future Research

6. Implications and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pew Research Center. Mobile Fact Sheet. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Technology. 2021. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/ (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Duran, R.L.; Kelly, L.; Rotaru, T. Mobile phones in romantic relationships and the dialectic of autonomy versus connection. Commun. Q. 2011, 59, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keane, K.L.; Hammond, S.I. Interpreting teasing through texting: The role of emoji, initialisms, relationships, and rejection sensitivity in ambiguous SMS. Can. J. Behav. Sci./Rev. Can. Sci. Comport. 2022, 56, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapierre, M.A.; Custer, B.E. Testing relationships between smartphone engagement, romantic partner communication, and relationship satisfaction. Mob. Media Commun. 2021, 9, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, J. Text messaging and connectedness within close interpersonal relationships. Marriage Fam. Rev. 2009, 45, 697–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schade, L.C.; Sandberg, J.; Bean, R.; Busby, D.; Coyne, S. Using technology to connect in romantic relationships: Effects on attachment, relationship satisfaction, and stability in emerging adults. J. Couple Relatsh. Ther. 2013, 12, 314–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, S.M.; Stockdale, L.; Busby, D.; Iverson, B.; Grant, D.M. “I luv u:)!”: A descriptive study of the media use of individuals in romantic relationships. Fam. Relat. 2011, 60, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-Ott, A.E.; Kelly, L.; Duran, R.L. The effects of cell phone usage rules on satisfaction in romantic relationships. Commun. Q. 2012, 60, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harari, G.M.; Müller, S.R.; Stachl, C.; Wang, R.; Wang, W.; Bühner, M.; Rentfrow, P.J.; Campbell, A.T.; Gosling, S.D. Sensing sociability: Individual differences in young adults’ conversation, calling, texting, and app use behaviors in daily life. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 119, 204–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastwick, P.W.; Keneski, E.; Morgan, T.A.; McDonald, M.A.; Huang, S.A. What do short-term and long-term relationships look like? Building the relationship coordination and strategic timing (ReCAST) model. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2018, 147, 747–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theiss, J.A. Modeling dyadic effects in the associations between relational uncertainty, sexual communication, and sexual satisfaction for husbands and wives. Commun. Res. 2011, 38, 565–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevareid, E.E.; Graham, K.; Guzzo, K.B.; Manning, W.D.; Brown, S.L. Have Teens’ Cohabitation, Marriage, and Childbearing Goals Changed Since the Great Recession? Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2023, 42, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, W.D. FP-13-12 Trends in Cohabitation: Over Twenty Years of Change, 1987–2010. 2013. Available online: https://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-of-arts-and-sciences/NCFMR/documents/FP/FP-13-12.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Wang, W.; Parker, K. Record Share of Americans Have Never Married [REPORT]. Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project. 2014. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2014/09/24/record-share-of-americans-have-never-married/ (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Bergdall, A.R.; Kraft, J.M.; Andes, K.; Carter, M.; Hatfield-Timajchy, K.; Hock-Long, L. Love and hooking up in the new millennium: Communication technology and relationships among urban African American and Puerto Rican young adults. J. Sex Res. 2012, 49, 570–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.J. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasilenko, S.A. Sexual behavior and health from adolescence to adulthood: Illustrative examples of 25 Years of research from Add Health. J. Adolesc. Health 2022, 71, S24–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, J.A.; McIsaac, C. Romantic relationships in adolescence. In Handbook of Adolescent Psychology: Contextual Influences on adolescent Development; Lerner, R.M., Steinberg, L., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 104–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cate, R.M.; Long, E.; Angera, J.J.; Draper, K.K. Sexual intercourse and relationship development. Fam. Relat. 1993, 42, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roels, R.; Janssen, E. Sexual and relationship satisfaction in young, heterosexual couples: The role of sexual frequency and sexual communication. J. Sex. Med. 2020, 17, 1643–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frederick, D.A.; Lever, J.; Gillespie, B.J.; Garcia, J.R. What keeps passion alive? Sexual satisfaction is associated with sexual communication, mood setting, sexual variety, oral sex, orgasm, and sex frequency in a national US study. J. Sex Res. 2017, 54, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallory, A.B.; Stanton, A.M.; Handy, A.B. Couples’ sexual communication and dimensions of sexual function: A meta-analysis. J. Sex Res. 2019, 56, 882–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.; Bostwick, E.; Anderson, C.; Gilchrist-Petty, E.; Long, S. How do computer-mediated channels negatively impact existing interpersonal relationships. In Contexts of the Dark Side of Communication; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 241–252. [Google Scholar]

- Sharabi, L.L.; Dykstra-DeVette, T.A. From first email to first date: Strategies for initiating relationships in online dating. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2019, 36, 3389–3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesi, J.L.; Fauber, R.L.; Gordon, E.A.; Heimberg, R.G. The specific importance of communicating about sex to couples’ sexual and overall relationship satisfaction. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2011, 28, 591–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, S.H.; Milhausen, R.R. Sexual desire and relationship duration in young men and women. J. Sex Marital. Ther. 2012, 38, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, S.; Rosen, N.O.; Corsini-Munt, S.; Maxwell, J.A.; Muise, A. Navigating Women’s Low Desire: Sexual Growth and Destiny Beliefs and Couples’ Well-Being. J. Sex Res. 2021, 58, 1118–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kershaw, T.; Arnold, A.; Gordon, D.; Magriples, U.; Niccolai, L. In the heart or in the head: Relationship and cognitive influences on sexual risk among young couples. AIDS Behav. 2012, 16, 1522–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, B.L.; Schlehofer-Sutton, M.M.; Villanueva, C.M.; Stritto, M.E.D.; Casad, B.J.; Feria, A. Let’s talk about sex: How comfortable discussions about sex impact teen sexual behavior. J. Health Commun. 2003, 8, 583–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, K.A.; Ivanov, B. Why not communicate?: Young women’s reflections on their lack of communication with sexual partners regarding sex and contraception. Int. J. Health Wellness Soc. 2012, 2, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astle, S.; McAllister, P.; Emanuels, S.; Rogers, J.; Toews, M.; Yazedjian, A. College students’ suggestions for improving sex education in schools beyond ‘blah blah blah condoms and STDs’. Sex Educ. 2021, 21, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leath, S.; Pittman, J.C.; Grower, P.; Ward, L.M. Steeped in shame: An exploration of family sexual socialization among Black college women. Psychol. Women Q. 2020, 44, 450–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharabi, L.L.; Caughlin, J.P. Usage patterns of social media across stages of romantic relationships. In Swipe Right for Love: The Impact of Social Media in Modern Romantic Relationships; Punyanunt-Carter, N., Wrench, J., Eds.; Lexington: Lanham, MD, USA, 2017; pp. 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Widman, L.; Nesi, J.; Choukas-Bradley, S.; Prinstein, M.J. Safe sext: Adolescents’ use of technology to communicate about sexual health with dating partners. J. Adolesc. Health 2014, 54, 612–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benotsch, E.G.; Snipes, D.J.; Martin, A.M.; Bull, S.S. Sexting, substance use, and sexual risk behavior in young adults. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2013, 52, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, C.J. Sexting behaviors among young Hispanic women: Incidence and association with other high-risk sexual behaviors. Psychiatr. Q. 2011, 82, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, E.J.; Eastwick, P.W.; Karney, B.R.; Reis, H.T.; Sprecher, S. Online dating: A critical analysis from the perspective of psychological science. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2012, 13, 3–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharabi, L.L.; Roaché, D.J.; Pusateri, K.B. Texting toward intimacy: Relational quality, length, and motivations in textual relationships. Commun. Stud. 2019, 70, 601–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, B.T.; Coyne, S.M. “Technoference”: The interference of technology in couple relationships and implications for women’s personal and relational well-being. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 2016, 5, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid FJ, M.; Reid, D. The expressive and conversational affordances of mobile messaging. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2010, 29, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtzman, S.; Kushlev, K.; Wozny, A.; Godard, R. Long-distance texting: Text messaging is linked with higher relationship satisfaction in long-distance relationships. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2021, 38, 3543–3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohadi, J.; Brown, B.; Trub, L.; Rosenthal, L. I just text to say I love you: Partner similarity in texting and relationship satisfaction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 78, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannebaum, M. College students’ use of technology to communicate with romantic partners about sexual health issues. J. Am. Coll. Health 2018, 66, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadian, R. Generation Communication: The Association of Communication Technology with Millennials’ Sexual Communication and Relationship Satisfaction. Ph.D. Dissertation, Alliant International University, Alhambra, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Oriza II, D.; Hanipraja, M.A. Sexting and sexual satisfaction on young adults in romantic relationship. Psychol. Res. Urban Soc. 2020, 3, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, C.; Cooke, J.E.; Temple, J.R.; Ly, A.; Lu, Y.; Anderson, N.; Rash, C.; Madigan, S. The prevalence of sexting behaviors among emerging adults: A meta-analysis. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2020, 49, 1103–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkett, M. Sex (t) talk: A qualitative analysis of young adults’ negotiations of the pleasures and perils of sexting. Sex. Cult. 2015, 19, 835–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trub, L.; Doyle, K.M.; Hubert, Z.M.; Parker, V.; Starks, T.J. Sexting to sex: Testing an attachment based model of connections between texting behavior and sex among heterosexually active women. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 128, 107097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, T.S.; Blackburn, K.M.; Perry, M.S.; Hawks, J.M. Sexting as an intervention: Relationship satisfaction and motivation considerations. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 2013, 41, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, M.A. Unpacking “sexting”: A systematic review of nonconsensual sexting in legal, educational, and psychological literatures. Trauma Violence Abus. 2017, 18, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, Z.P.; Wilson, C.; Scott, G.G. Sextual intercourse: Considering social–cognitive predictors and subsequent outcomes of sexting behavior in adulthood. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2019, 48, 2367–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klettke, B.; Hallford, D.J.; Clancy, E.; Mellor, D.J.; Toumbourou, J.W. Sexting and psychological distress: The role of unwanted and coerced sexts. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2019, 22, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmeyer, J.J.; Herbenick, D.; Eastman-Mueller, H. Sexting with romantic partners during college: Who does it, who doesn’t and who wants to. Sex. Cult. 2022, 26, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinberg, M.; Ram, N. Do new romantic couples use more similar language over time? Evidence from intensive longitudinal text messages. J. Commun. 2021, 71, 454–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouin, M.; Landgraff, C. Texting, sexting, and attachment in college students’ romantic relationships. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catania, J.A.; Gibson, D.R.; Chitwood, D.D.; Coates, T.J. Methodological problems in AIDS behavioral research: Influences on measurement error and participation bias in studies of sexual behavior. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 108, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiClemente, R.J.; Swartzendruber, A.L.; Brown, J.L. Improving the validity of self-reported sexual behavior: No easy answers. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2013, 40, 111–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassman, J.R.; Baumler, E.R.; Coyle, K.K. Inconsistencies in Adolescent Self-Reported Sexual Behavior: Experience from Four Randomized Controlled Trials. Prev. Sci. 2023, 24, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, E.B.; Peterson, Z.D. Investigating the impact of inquiry mode on self-reported sexual behavior: Theoretical considerations and review of the literature. J. Sex Res. 2012, 49, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussong, A.M.; Jensen, M.R.; Morgan, S.; Poteat, J. Collecting text messages from college students: Evaluating a novel methodology. Soc. Dev. 2020, 30, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwandt, T.A. Three epistemological stances for qualitative inquiry: Interpretivism, hermeneutics, and social constructionism. In Handbook of Qualitative Research; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 189–213. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D.R. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am. J. Eval. 2006, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, M.L. Social Intercourse: From Greeting to Goodbye; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Macapagal, K.; Greene, G.J.; Rivera, Z.; Mustanski, B. “The best is always yet to come”: Relationship stages and processes among young LGBT couples. J. Fam. Psychol. 2015, 29, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesi, J.L.; Conner, B.T.; Gordon, E.A.; Fauber, R.L.; Kim, K.H.; Heimberg, R.G. On the relationship among social anxiety, intimacy, sexual communication, and sexual satisfaction in young couples. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2013, 42, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, J.; Warber, K.M.; Makstaller, D.C. The role of Facebook in romantic relationship development: An exploration of Knapp’s relational stage model. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2013, 30, 771–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betcher, W.R. Intimate play and marital adaptation. Psychiatry 1981, 44, 13–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzini, D.G.; Stack, E.R.; Martincin, P.D.; Davis, C.P. The effect of reminiscing about laughter on relationship satisfaction. Motiv. Emot. 2007, 31, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.A. Humor in long-term romantic relationships: The association of general humor styles and relationship-specific functions with relationship satisfaction. West. J. Commun. 2013, 77, 272–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.A. Humor in romantic relationships: A meta-analysis. Pers. Relatsh. 2017, 24, 306–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miczo, N.; Averbeck, J. Perceived partner humor use and relationship satisfaction in romantic pairs: The mediating role of relational uncertainty. Humor-Int. J. Humor Res. 2020, 33, 513–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didonato, T.E.; Bedminster, M.C.; Machel, J.J. My funny valentine: How humor styles affect romantic interest. Pers. Relatsh. 2013, 20, 374–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keltner, D.; Capps, L.; Kring, A.M.; Young, R.C.; Heerey, E.A. Just teasing: A conceptual analysis and empirical review. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiota, M.N.; Campos, B.; Keltner, D.; Hertenstein, M.J. Positive emotion and the regulation of interpersonal relationships. In The Regulation of Emotion; Taylor & Francis: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2004; Volume 68. [Google Scholar]

- DiDonato, T.E.; Jakubiak, B.K. Strategically Funny: Romantic Motives Affect Humor Style in Relationship Initiation. Eur. J. Psychol. 2016, 12, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doohan, E.M.; Manusov, V. The communication of compliments in romantic relationships: An investigation of relational satisfaction and sex differences and similarities in compliment behavior. West. J. Commun. (Incl. Commun. Rep.) 2004, 68, 170–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marigold, D.C.; Holmes, J.G.; Ross, M. More than words: Reframing compliments from romantic partners fosters security in low self-esteem individuals. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 232–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satinsky, S.; Reece, M.; Dennis, B.; Sanders, S.; Bardzell, S. An assessment of body appreciation and its relationship to sexual function in women. Body Image 2012, 9, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laus, M.F.; Almeida, S.S.; Klos, L.A. Body image and the role of romantic relationships. Cogent Psychol. 2018, 5, 1496986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, A.L.; Makhanova, A.; Hicks, L.L.; French, J.E.; McNulty, J.K.; Bradbury, T.N. Quantifying the sexual afterglow: The lingering benefits of sex and their implications for pair-bonded relationships. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 28, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moor, A.; Haimov, Y.; Shreiber, S. When Desire Fades: Women Talk About Their Subjective Experience of Declining Sexual Desire in Loving Long-term Relationships. J. Sex Res. 2021, 58, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avtgis, T.A.; West, D.V.; Anderson, T.L. Relationship stages: An inductive analysis identifying cognitive, affective, and behavioral dimensions of Knapp’s relational stages model. Commun. Res. Rep. 1998, 15, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez-Aller, Á.; Postigo, Á.; Montes-Álvarez, P.; González-Primo, F.J.; García-Cueto, E. Humor as a protective factor against anxiety and depression. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2020, 20, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Koning, E.; Weiss, R.L. The relational humor inventory: Functions of humor in close relationships. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 2002, 30, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, E.E. The involvement of sense of humor in the development of social relationships. Commun. Rep. 1995, 8, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.; Kunkel, A.; Dennis, M.R. “Let’s (not) talk about that”: Bridging the past sexual experiences taboo to build healthy romantic relationships. J. Sex Res. 2011, 48, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, N.; Bensman, L.; Hatfield, E. Culture and sexual self-disclosure in intimate relationships. Interpersona Int. J. Pers. Relatsh. 2013, 7, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNeil, S.; Byers, E.S. Dyadic assessment of sexual self-disclosure and sexual satisfaction in heterosexual dating couples. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2005, 22, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.D.; Weigel, D.J. Exploring a contextual model of sexual self-disclosure and sexual satisfaction. J. Sex Res. 2018, 55, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L.; Miller-Ott, A.E. Perceived miscommunication in friends’ and romantic partners’ texted conversations. South. Commun. J. 2018, 83, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.D.; Lavner, J.A.; Mund, M.; Zemp, M.; Stanley, S.M.; Neyer, F.J.; Impett, E.A.; Rhoades, G.K.; Bodenmann, G.; Weidmann, R.; et al. Within-Couple Associations Between Communication and Relationship Satisfaction Over Time. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2022, 48, 534–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freihart, B.K.; Sears, M.A.; Meston, C.M. Relational and interpersonal predictors of sexual satisfaction. Curr. Sex. Health Rep. 2020, 12, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallory, A.B. Dimensions of couples’ sexual communication, relationship satisfaction, and sexual satisfaction: A meta-analysis. J. Fam. Psychol. 2022, 36, 358–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.C.; Robinson, W.D.; Seedall, R.B. The role of sexual communication in couples’ sexual outcomes: A dyadic path analysis. J. Marital Fam. Ther. 2018, 44, 606–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, M.L.; Vangelisti, A.L.; Caughlin, J.P. Interpersonal Communication and Human Relationships, 7th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil, S.; Byers, E.S. Role of sexual self-disclosure in the sexual satisfaction of long-term heterosexual couples. J. Sex Res. 2009, 46, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litzinger, S.; Gordon, K.C. Exploring relationships among communication, sexual satisfaction, and marital satisfaction. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2005, 31, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mark, K.P.; Murray, S.H. Gender differences in desire discrepancy as a predictor of sexual and relationship satisfaction in a college sample of heterosexual romantic relationships. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2012, 38, 198–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vowels, L.M.; Mark, K.P. Strategies for mitigating sexual desire discrepancy in relationships. Arch Sex Behav. 2020, 49, 1017–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbenick, D.; Mullinax, M.; Mark, K. Sexual desire discrepancy as a feature, not a bug, of long-term relationships: Women’s self-reported strategies for modulating sexual desire. J Sex Med. 2014, 11, 2196–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willoughby, B.J.; Farero, A.M.; Busby, D.M. Exploring the effects of sexual desire discrepancy among married couples. Arch Sex Behav. 2014, 43, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, N.O.; Bailey, K.; Muise, A. Degree and direction of sexual desire discrepancy are linked to sexual and relationship satisfaction in couples transitioning to parenthood. J. Sex Res. 2018, 55, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Gao, S.; Xu, L.; Zheng, X.; Ma, X.; Luo, L.; Kendrick, K.M. Women prefer men who use metaphorical language when paying compliments in a romantic context. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Yang, Q.; Ma, X.; Becker, B.; Li, K.; Zhou, F.; Kendrick, K.M. Men who compliment a Woman’s appearance using metaphorical language: Associations with creativity, masculinity, intelligence and attractiveness. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byers, E.S. Beyond the birds and the bees and was it good for you?: Thirty years of research on sexual communication. Can. Psychol./Psychol. Can. 2011, 52, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmstead, S.B. A Decade Review of Sex and Partnering in Adolescence and Young Adulthood. J. Marriage Fam. 2020, 82, 769–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, P.B.; Kleiner, S.; Geist, C.; Cebulko, K. Conventions of Courtship: Gender and Race Differences in the Significance of Dating Rituals. J. Fam. Issues 2011, 32, 629–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, L.; Blair, K. The Intimate Relationships of Sexual and Gender Minorities. In The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships; Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology; Vangelisti, A., Perlman, D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, S.J.; Huberman, J.S.; Bouchard, K.N.; McInnis, M.K.; Pukall, C.F.; Chivers, M.L. Effects of individual difference variables, gender, and exclusivity of sexual attraction on volunteer bias in sexuality research. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2019, 48, 2403–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guntuku, S.C.; Li, M.; Tay, L.; Ungar, L.H. Studying cultural differences in emoji usage across the east and the west. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Munich, Germany, 11–14 June 2019; Volume 13, pp. 226–235. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, D.; Baiocco, R.; Lonigro, A.; Pompili, S.; Zammuto, M.; Di Tata, D.; Morelli, M.; Chirumbolo, A.; Di Norcia, A.; Cannoni, E.; et al. Love in quarantine: Sexting, stress, and coping during the COVID-19 lockdown. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2021, 20, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maes, C.; Vandenbosch, L. Physically distant, virtually close: Adolescents’ sexting behaviors during a strict lockdown period of the COVID-19 pandemic. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 126, 107033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Montanaro, E.; Temple, J.; Ersoff, M.; Jules, B.; Jaliawala, M.; Kinkopf, D.; Webb, S.; Moxie, J. “Just lmk When You Want to Have Sex”: An Exploratory–Descriptive Qualitative Analysis of Sexting in Emerging Adult Couples. Sexes 2024, 5, 9-30. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes5010002

Montanaro E, Temple J, Ersoff M, Jules B, Jaliawala M, Kinkopf D, Webb S, Moxie J. “Just lmk When You Want to Have Sex”: An Exploratory–Descriptive Qualitative Analysis of Sexting in Emerging Adult Couples. Sexes. 2024; 5(1):9-30. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes5010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleMontanaro, Erika, Jasmine Temple, Mia Ersoff, Bridget Jules, Mariam Jaliawala, Dara Kinkopf, Samantha Webb, and Jessamyn Moxie. 2024. "“Just lmk When You Want to Have Sex”: An Exploratory–Descriptive Qualitative Analysis of Sexting in Emerging Adult Couples" Sexes 5, no. 1: 9-30. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes5010002

APA StyleMontanaro, E., Temple, J., Ersoff, M., Jules, B., Jaliawala, M., Kinkopf, D., Webb, S., & Moxie, J. (2024). “Just lmk When You Want to Have Sex”: An Exploratory–Descriptive Qualitative Analysis of Sexting in Emerging Adult Couples. Sexes, 5(1), 9-30. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes5010002