Abstract

An online survey was completed by a convenience sample of 495 students to assess attitude toward polyamorous targets as an outgroup using 0–100 feeling thermometers. Also assessed was the likelihood of dating a polyamorous partner. These two measures were only weakly related for women participants but modestly related for men participants. Overall, feeling thermometer averages were favorable (66%) but dating likelihood was very low, with 89% rating dating a polyamorous partner as unlikely. Women were slightly more favorable toward polyamorous targets than were men but target gender showed no effect (i.e., ratings of polyamorous men were the same as those of polyamorous women). However, men were slightly more willing to date a polyamorous partner than were women. In terms of personality and individual difference variables as predictors of attitudes, authoritarianism, erotophobia–erotophilia, and participant sexual orientation accounted for a quarter of the variance in feeling thermometer ratings of polyamorous targets. Specifically, those who had lower authoritarianism, were more comfortable with sexuality, and were sexual minority in orientation were likely to rate the polyamorous targets the most favorably. Individual difference variables did not predict willingness to date a polyamorous partner consistently across gender and sexual orientation participant subgroups; the most consistent predictors were sociosexuality and erotophobia–erotophilia. This study adds to our knowledge in a nascent area of sexual attitude and discrimination research—it demonstrates the differences between rating an outgroup person and attitude toward engaging with them personally. The latter appears to involve more complexity in terms of the relationship with personality and the type of social perceiver. More research is needed into the differentiation between general ratings of others who engage in non-mainstream, stigmatized sexual practices versus when the ratings involve personal involvement or behavior of the social perceiver (i.e., such as dating).

1. Introduction

Polyamory is thought of as a relationship orientation such that a person desires or is engaged in romantic relationships involving more than the two partners that comprise typical monogamous relationships [1]. It is a form of consensual non-monogamy (CNM) in which about 10–20% of US people have engaged [2,3]. CNM and polyamory are often used synonymously but CNM is broader and includes open relationships as well as swinging [2]. Our focus will be polyamory but some studies use the broader CNM term. While polyamory can be argued to be a behavior, it has been characterized as an identity [1]. Probably because of the threat to dominant monogamy, polyamory—as a concept—tends to be stigmatized [4].

Stigma is the feeling that one is rejected or disparaged because of some undesirable characteristic. Enacted sexual stigma [5] regarding polyamory has been documented, mostly described in microaggressive form [6,7,8,9,10]. The stigma identified by polyamorous persons likely is a result of the fact that attitudes are not overly positive toward polyamorous people. For example, Moors, Gesselman, and Garcia [11] found that, of those who had no personal interest in polyamory (i.e., would view people engaging in polyamory as an outgroup), only 14.2% indicated respect for those who engage in polyamory. Similarly, on 18 attributes, Matsick et al. [12] found that social perceiver ratings of CNM individuals were quite unflattering (i.e., high on dirty, low on morality, relationship satisfaction, selflessness). In comparative terms, Cragun and Sumerau [13] investigated attitudes toward five target identity groups (using an 11-option feeling thermometer, with 100 being warmest and 1 being coldest). Although targets were not compared statistically across groups, feeling thermometer ratings of polygamists (a subgroup of polyamory, defined as people who believe in or want multiple spouses at the same time; ~49%) were considerably lower than heterosexuals (~90%), homosexuals (~80%), bisexuals (~75%), and transgender individuals (~68%).

1.1. Social Perceivers Evaluations of Polyamory

Attitudes are overall evaluations of persons, objects, or ideas as experienced or expressed by a social perceiver. The theoretical underpinnings of attitudes are beliefs [14], but researchers often use aggregated beliefs to represent attitudes. Further, researchers assess evaluations of polyamory or CNM using various descriptors (e.g., perceptions of emotions, traits, or characteristics of the target being evaluated). Attitudes can be measured explicitly, by asking participants outright to indicate their evaluation, or implicitly, by assessing reaction time to target-related stimuli. Typically, study participants who are outgroup members are the social perceivers of interest as people are more likely to rate outgroup members more negatively than ingroup members. Social cognitive processes of ingrouping and outgrouping give rise to preferential attitudes and behavior [15].

Classic attitude evaluation (e.g., good/bad, like/dislike) tends to find that participants rate polyamorous or CNM targets neutral-to-slightly negatively on average [16,17,18]; although the study by Rodrigues, Aybar Camposno, and Lopes [19] was an exception, where the average evaluation was neutral-to-slightly positive. Using an emotion rating process, Rodrigues and colleagues [7,17] found evidence of greater dehumanization of CNM (polyamorous, open) versus monogamous vignette targets.

CNM targets have been found to be rated less positively using trait or characteristic (e.g., morality, trustworthiness, promiscuity, relationship satisfaction) evaluations, primarily using vignette descriptions [17,19,20,21,22,23,24]. A study of therapists found CNM couple vignettes being rated less positively on a series of morality, competence, and relationship satisfaction traits than monogamous counterparts [25]. Hutzler et al. [26] found equivocal perceptions of polyamorous persons, with some attributes being rated positively (e.g., lower jealousy, more attractive) while others were more negative (e.g., lower relationship satisfaction) when compared to the scale midpoint. Generally, the comparative attitude studies would best be described as finding polyamorous or CNM targets judged less positively relative to monogamous counterparts in terms of traits or characteristics. This can be termed a “devil effect”—the opposite of a “halo” effect—whereby a sometimes irrelevant component of a person’s life is used to judge all aspects of the person [20].

A seven-item polyamory-related belief scale was constructed by Johnson et al. (the Attitudes toward Polyamory scale) [27]. Average polyamory belief ratings on this instrument were neutral-to-slightly negative [27,28,29]. In contrast, Cardoso et al.’s [30] Portuguese sample expressed more favorable polyamory beliefs, with an average score representing slightly-to-moderately positive average ratings. Slightly more broad in target scope (i.e., CNM vs. simply polyamory), Cohen and Wilson [31] created an eight-item CNM Attitude scale and found that participants were neutral-to-slightly positive regarding beliefs about consensual non-monogamy. Others have replicated these average neutral-to-slightly positive ratings on this scale [32,33]. Thus, while there is evidence of negativity in these explicit belief scales, attitudes toward polyamory have not been found to be uniformly nor absolutely negative.

Using the more subtle implicit association task procedure, two studies found that most participants had an automatic moderate or strong preference for monogamy over polyamory [29,34]. Thompson, Moore, Haedtke, and Karst [18] found that implicit CNM attitudes (e.g., “group sex”, “open marriage”) were neutral while implicit attitudes toward monogamy were positive. The same monogamy preferential patterns have been observed for social distance outcomes [20]: while social distance ratings of monogamous and CNM targets were favorable overall, participants were willing to be relationally closer to monogamous targets (i.e., close friend) compared to polyamorous targets (i.e., neighbor/co-worker). Aside from the work of Balzarini et al. [20], what is conspicuously absent from this literature is evaluation of intention to engage in behavior. Intentions are often used as a proxy for behavior; willingness or likelihood judgements regarding an action are theoretical determinants of behavior [14]. Examples might be “How willing are you to sign a petition to legalize marriage between three people?” or “How likely is it that you would vote for a candidate who engages in CNM?” or “Would you be willing to write an essay supporting CNM?”.

In sum, most studies, regardless of research design, find that perceivers are generally slightly negative or neutral toward polyamory or CNM; this is often qualified for positive or preferential ratings of monogamy—consistent with what would be expected by theory. Like traditional -isms (e.g., sexism, racism, heterosexism), CNM attitudes are not necessarily negative but rather there is a strong preference for monogamy (the dominant ingroup). Aside from knowing what attitudes are held, scholars are interested in what predicts CNM attitudes.

1.2. Demographic Characteristics of the Social Perceiver

In addition to assessing attitudes toward polyamory or CNM, some researchers have investigated what characteristics of the social perceiver matter in theoretically determining or predicting these attitudes. Some of these person characteristics are demographic in nature—such as gender, sexual orientation, or religious orientation of the social perceiver—while others are psychological or personality-oriented factors (e.g., authoritarianism).

A substantial number of studies have found no differences in attitudinal ratings of polyamory or CNM between women and men [16,21,26,27,29,31,35,36,37,38] (note: [26,27] used the same data set). However, a few gender differences have been documented. Some have found women to be more negative than men (polygamist target [13]; extradyadic relationship behaviors tolerance [39]; implicit attitudes [18]; on the CNM Attitude scale [33]). In contrast, Kaufman et al. [40] found that women were more supportive of polyamorous marriage than men. Thompson et al. [18] found women to be more favorable toward CNM targets on judgments of their cognitive abilities, morality, and relationship satisfaction, although this was a very weak effect. Generally, there appear to be few or inconsistent gender differences in polyamory or CNM attitudes.

When investigated, most studies find that those with a minority sexual orientation are more favorable in ratings of CNM targets or beliefs when compared to heterosexual participants [23,28,31,33,35,39]. In contrast, no differences were found between heterosexual and sexual orientation minority participants on an implicit attitude measure about CNM [18]. Further, Cragun and Sumerau [13] found no polygamist feeling thermometer rating differences as a function of participant sexual orientation. These differential findings might be a function of outcome variable diversity.

1.3. Individual Differences: Religion and Political Orientation

While individual difference (e.g., authoritarianism, social dominance) measures as predictors of attitudes toward sexual orientation and gender identity minorities have been investigated extensively [41], research using such constructs as predictors of attitudes toward CNM or polyamory persons is nascent. Receiving perhaps the most attention have been measures related to religion and political orientation.

Religion or religiosity has been found to correlate moderately with various polyamory or CNM attitudinal measures [13,26,27,36,37]. Political orientation, typically measured on a conservative-to-liberal scale or via Republican-or-Democrat party endorsement, has been found to be weakly-to-moderately correlated with polyamory and CNM attitudes [26,27,36,37]. Together, political orientation and religiosity accounted for between 3% and 8% of the variance in social distance ratings tolerated for CNM targets [20]. These two variables might be rough approximations of a participant’s general conservatism.

1.4. The Authoritarian Personality

Authoritarianism is a personality disposition characterized by social conservatism. People who are high in authoritarianism are those who value obedience to authority, view the world as an unsafe or dangerous place, are intolerant of those who they perceive as external to their social groups, and endorse strictness and order (e.g., punitive punishment; adherence to rules, regulations, and superiors). Consequently, those high in authoritarianism adhere to social norms as this fosters social order (which is a very comfortable state). In Big-Five personality trait terms, authoritarianism has been characterized as those who are low on openness and high on conscientiousness. Authoritarianism is linked with conservative ideology and a concrete worldview. High authoritarians are often politically conservative and highly religious. In particular, people who are high in authoritarianism are very sensitive to threats to social order [42,43].

Several individual difference variables, which reflect authoritarianism, have been studied in relation to attitudes toward polyamory and CNM and support the relevance of authoritarianism. Right-wing authoritarianism predicted negative attitudes on the Attitudes toward Polyamory scale [27]. Social conformity was a critical multiple regression predictor of this scale too, such that those who valued social conformity were more negative toward polyamory [28]. Social dominance orientation and moral decision-making belief systems also predicted more negative CNM attitudes [35]. The personality trait of openness was found to predict positive CNM attitudes [44]. Perhaps tangentially related to authoritarianism, a heterosexism instrument was moderately strongly related to polyamory attitudes [30]; the more rejecting of heterosexism (e.g., disagreeing with ideas like same-sex marriage undermining societal foundations), the more favorable participants were toward polyamory. In short, there is some emerging evidence that authoritarian personality may predict negative attitudes toward polyamory or CNM.

1.5. Sexuality and Relationships

Logically, psychological attributes regarding sexuality would relate to attitudes toward polyamory or CNM. Sociosexuality can be thought of as a person’s motivation or orientation in relation to uncommitted sexuality [45]. Three investigations have explored sociosexual orientation and CNM attitudes and all found sociosexuality predictive of attitudes [22,31,46]. Johnson et al. [27] found that erotophobia–erotophilia, a learned psychological avoidance–approach response to sexuality, correlated moderately with the Attitudes toward Polyamory scale; those who were more erotophilic were more positive toward polyamory. Johnson et al. [27] also described some weak correlations of–sexuality self-concept variables with attitudes toward polyamory such that those who were higher in sexual sensation-seeking, those who had a greater need for sex, and those who were greater sexual risk-takers were more positive toward polyamory.

Cognitive relationship styles have also been investigated in relation to CNM attitudes, including attachment style, with both avoidant and anxious styles weakly relating such that those eschewing relational closeness were more favorable toward CNM [46] while those fearing abandonment were less positive toward CNM [44]. Flicker and Sancier-Barbosa [28] found that pragmatic and mania love styles were weakly related to polyamory attitudes such that those endorsing these love styles were less accepting of polyamory. Zero-sum romantic thinking—whereby love is considered finite, where polyamory would result in splitting love amongst partners—strongly predicts rejection of CNM [21,35]. In sum, cognitive styles or personality dispositions related to sexuality and/or relationships may exert some influence on how polyamory is perceived.

1.6. The Current Study

1.6.1. Measuring Attitudes toward Polyamorous Targets

This investigation explores attitudes toward polyamorous persons by employing feeling thermometers as the dependent measures. Feeling thermometers have been used infrequently in relation to assessing polyamorous or CNM persons, with only Cragun and Sumerau [13] using an options-limited thermometer while assessing feelings about polygamists. Feeling thermometers assess overall evaluations of a target and the single item has been found to correlate well with aggregated beliefs and classic semantic differential scales in relation to other sexual minorities (e.g., asexuals; [47]). Much research has investigated participant’s willingness to engage in polyamory [18,26,28,30,33,44,46]; this variable assesses behaviors of the self and is less about the “other”. In contrast, we used a scale asking about willingness to date a polyamorous person. This is a social distance type of measure (i.e., “would you tolerate dating a person with this identity characteristic?”) which may have implications about the perceiver’s self but is more about the “other”. To date, only Balzarini and colleagues [20] have investigated attitudes toward polyamory using an ordinal social distance assessment. As a dependent measure, this willingness to date a polyamorous person may invoke more self-related psychological implications than merely assessing an outgroup member (i.e., “not my cup of tea; live and let live”) because of the addition of context; an assessment of willingness to date means accepting someone with this relationship philosophy into one’s intimate sphere. While dating someone who is polyamorous would not necessitate participation in polyamory, it might involve self-related psychological threat (“My partner might want to have another partner/might currently have another partner, what does this mean for me or say about me?”) or stigma-by-association (“What will people think of me being involved in a polyamorous relationship/with a polyamorous person?”). These two measures are somewhat analogous to asking heterosexual people “How do you feel about this homosexual person?” versus “How would you react if a homosexual person hit on/came on/made a pass at you?” In other words, the context of dating a polyamorous person thus may invoke threat to the self. Thus, the first research goal is to investigate attitudes toward polyamory using these two previously under-examined dependent measures.

1.6.2. Theoretical Framework

While some studies have explored predictors of attitudes toward polyamory and CNM, only a few [28,46] have investigated personality and individual difference predictors of attitudes toward polyamory/CNM within a theoretical framework. Consequently, the goal of the current study is to investigate personality characteristics as predictors of feelings toward polyamorous persons and willingness to date a polyamorous partner. We approach the study of attitudes toward polyamorous people from the perspective of intergroup threat theory [48,49], the major premise of which is that, when realistic and symbolic threats are perceived by the dominant group toward either the individual or the group, negative attitudes will result. Specifically, the contemplation of dating a polyamorous person may evoke symbolic threat, such as a threat to self-identity because of the underlying psychological meaning of the partner wanting to date another (e.g., relationship apprehension) or that contemplation of being involved with a polyamorous person might be inconsistent with one’s morals or values. In addition, dating a polyamorous person might constitute an actual threat, such as reputational damage or sexual health risks [35]. According to intergroup threat theory, the threats arising from these types of apprehension are thought to give rise to negative emotions toward, cognitions about, and behaviors toward the outgroup who evoked the threat [49].

Intergroup threat theory posits that there are individual differences in sensitivity to threat. Generally, Stephan et al. [49] argue that people who prefer strict social order, hierarchy, conservatism, and strong belief systems (e.g., religious adherence) tend to have personality attributes that foster greater threat perception. Two specific personality traits or ideological dimensions that are thought to serve as motivational factors in threat perception are authoritarianism and social dominance orientation. In the current study, we included right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation, as well as religiosity and intergroup disgust sensitivity, as predictors of polyamory attitudes. Sex role attitudes, in the form of hostile and benevolent sexism, may also be relevant as these support traditional, conservative, and hierarchical roles in relation to men and women. As polyamory is an unconventional form of relational sexuality, some sex-related dispositional variables were considered as potential predictors of polyamory ratings (i.e., sociosexuality, erotophobia–erotophilia). Generally, polyamory would likely be viewed as a threat to the traditional man–woman–family societal structure. As a form of unconventional sexuality, polyamory would be a threat to those having traditional sexuality and gender values and dispositions.

1.6.3. Analysis Plan and Hypotheses

Using the two types of dependent measures, descriptive statistics are presented and compared to assess negative attitudes toward a polyamorous man and a polyamorous woman, along with the likelihood that one would date a polyamorous man or a polyamorous woman. Potential gender and sexual orientation differences in polyamory ratings could exist, so these were explored. Generally, women have been found to be more positive than men toward sexual and gender minorities, but the research regarding gender differences in polyamory attitudes is equivocal. Sexual orientation minorities are expected to be the most favorable toward polyamorous targets as this group, very consistently in past research, has been found to be the most favorable toward CNM. This might be because sexual minorities may experience less threat from polyamory than heterosexuals as they perhaps view polyamorous individuals as part of their ingroup. Alternatively, sexual minorities are more likely to practice CNM and thus may be more familiar with or knowledgeable of those who practice CNM [31] (knowledge/familiarity is a factor in threat reduction [49]). Polyamorous partner dating likelihood is separated by heterosexual women, heterosexual men, and bisexual women participants.

Regarding the personality and individual difference predictors of polyamory targets, those people who are higher in authoritarianism, higher in social dominance, higher in religiosity, and express greater intergroup disgust are expected to have less positive evaluations of polyamorous targets. These conservatism-oriented individuals are theorized to experience greater threat from any outgroup that challenges their views of established social order, mores, and traditions. Further, those who express greater sexism, more erotophobia, and a restricted sociosexual orientation are hypothesized to be more negative toward polyamorous targets as polyamory may evoke threat to sexuality value systems. In short, relationships are explored between ratings of polyamory and personality constructs representing general and sexual conservatism through correlation and multiple regression analysis. Gender and sexual orientation differences are considered in these analyses where possible.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The participants were a convenience sample of 495 undergraduate students, enrolled at a mid-sized Canadian university, who participated in an online survey in order to earn course research credit in psychology or related social science courses. The most popular program of study was Arts (57.8%), and then Sciences (i.e., applied health, environmental, and general; 35.1%). The average age was 20.7 years (sd = 4.22, ranging from 17 to 52 years). The sample was mostly Asian (23.5% South Asian and 20.8% East Asian/Pacific Islander) or white (40.6%) and mostly women (80.9%; 19.1% described themselves as men, 11 identified as another gender, and 7 omitted the gender item). From the options provided, three sexual orientations were derived: exclusively heterosexual (53.4%), mostly heterosexual (21.3%), and sexual orientation minority (25.3%). For relationship status, most identified as single (61.0%). Only one participant indicated that they were involved in a polyamorous relationship.

2.2. Procedure

Using the Qualtrics online platform, participants accessed an information letter and consent form and then proceeded to the survey. Participants could omit any items to which they did not wish to respond; consequently, the n across analyses sometimes differs (i.e., pairwise rather than listwise deletion was implemented). At the end of the survey, there was a post-study consent form as well as a debriefing sheet and resource list. The instruments used in the current study were embedded in a questionnaire addressing many controversial sexual issues [47].

2.3. Survey Instrument

2.3.1. Dependent Variables

Two single-item feeling thermometers were used to assess attitudes toward polyamorous persons. The words “Polyamorous men” were included with the following definition: “men who have more than one romantic relationship at a time, with full knowledge and consent by all partners involved”. Participants selected a favorability rating ranging from 0 (unfavorable) to 100 (favorable). Similarly, participants were presented with “Polyamorous women” defined as “women who have more than one romantic relationship at a time, with full knowledge and consent by all partners involved” on which they rated the target on the 0-to-100 favorability scale. These two followed completion of eleven other ratings of sexual orientation and gender identity targets (e.g., bisexual men, trans women) on the same feeling thermometer.

Two additional items served as dependent measures. Participants were given the following directions: “Please approach these questions as if you were single. If given the chance, how likely would you be to date someone who is a…” polyamorous man as well as polyamorous woman. These ratings were preceded by the same 11 diverse sexual orientation and gender identity targets as the feeling thermometers. Participants responded on an 8-point scale with options of Very Unlikely, Unlikely, Moderately Unlikely, Slightly Unlikely, Slightly Likely, Moderately Likely, Likely, and Very Likely.

In order for these items to be meaningfully interpreted, participants who were exclusively and mostly heterosexual men were selected when assessing the likelihood of dating a polyamorous woman. Similarly, exclusively and mostly heterosexual women participants were selected when assessing the likelihood of dating a polyamorous man. The variety within the sexual minority orientations coupled with participant gender produced very small cells (e.g., there were only 12 men who identified with a sexual minority sexual orientation, only half of whom identified as homosexual or mostly homosexual) and thus prohibited meaningful analysis. However, there were enough bisexual/pansexual women to consider them as a separate sexual orientation group.

2.3.2. Personality and Individual Difference Variables

Under the demographic section of the survey, prior to attitudinal assessments, participants were asked how religious they were on a 5-point scale (1 = not-at-all religious, 2 = slightly religious, 3 = moderately religious, 4 = very religious, 5 = extremely religious). In past research [50], this single item correlated quite well with the Religious Fundamentalism scale (r = 0.69). A series of personality and individual difference variables were assessed after the attitudinal measures were completed.

- Altemeyer’s [51] 24-item Right-Wing Fundamentalism Scale was included to measure authoritarianism. A sample item is: “Laws have to be strictly enforced if we are going to preserve our way of life”.

- The 8-item Social Dominance Orientation Scale (SDO7) [52] assessed preference for group hierarchical dominance (e.g., “An ideal society requires some groups to be on top and others to be on the bottom”) and anti-egalitarianism (e.g., “It is unjust to try to make groups equal”) [53].

- The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory [54] produced overt (11 Hostile Sexism items; e.g., “Women are too easily offended”) and covert (11 Benevolent Sexism items;” Women should be cherished and protected by men“) sexism scales.

- The 21-item Sexual Opinion Survey [55] was created as an indicator of learned, affective responses to sexuality and sexual content; scale responses represent erotophobia (e.g., “I do NOT enjoy daydreaming about sexual matters”) on one end to erotophilia (e.g., “I think it would be very entertaining to look at erotica”) on the other.

- Sociosexuality Scale [45,56] measured orientation toward casual sexuality using nine questions. This individual difference variable includes behavioral, fantasy, and attitudinal questions about non-committed sexuality (e.g., “Sex without love is OK”).

- Intergroup Disgust Sensitivity [57] was designed to assess negative affect, such as revulsion and disgust, toward ethnic outgroups (8 items including: “When socializing with members of a stigmatized group, one can easily become tainted by their stigma”). This is a general orientation toward outgroup members.

Instruments were averaged across items to produce a single score for each construct. Most items were rated on a disagree-to-agree scale (see Table 1 for descriptive statistics).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations of individual difference measures with polyamory feeling thermometers and polyamory dating likelihood.

3. Results

3.1. Ratings of Feeling Thermometers toward Polyamorous Targets

In terms of overall favorability ratings, polyamorous men and polyamorous women were rated somewhat positively (i.e., Ms = 65.47%, sd = 33.77% and 66.73%, sd = 34.20%, respectively). These two ratings were strongly correlated (r(490) = 0.94, p < 0.001). The scale could range from 0 to 100 and 28.0% gave polyamorous men a score of 100% while 30.6% gave polyamorous women a 100% favorability rating. Conversely, 5.1% and 5.5% gave the targets a rating of zero.

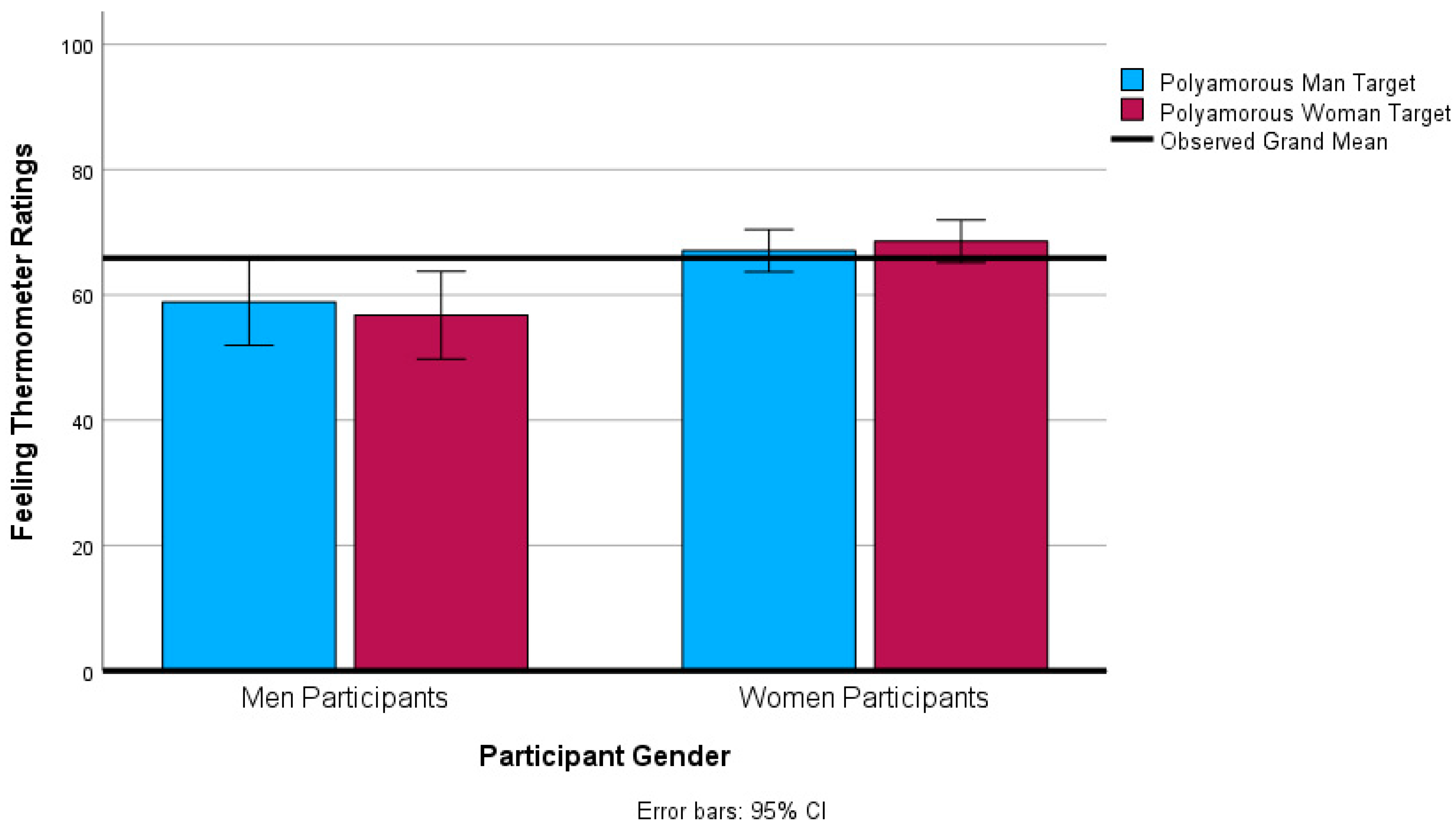

3.1.1. Gender and Polyamorous Target Ratings

Testing for the effects of gender of polyamorous target, gender of participant, and the interaction of these two variables, a 2 × 2 ANOVA was conducted with gender of polyamorous target as a repeated-measures variable and participant gender as a between-subjects’ variable. There was no main effect of polyamorous target gender (F(1,470) = 0.27, ns, ηp2 = 0.00) and a very weak main effect of participant gender (F(1,470) = 6.58, p < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.01). Women (M = 67.80, SE = 1.71) rated polyamorous targets slightly more positively than men (M = 57.81, SE = 3.50) but this effect size is negligible. The interaction was statistically significant but the effect size was insubstantial (F(1,470) = 9.25, p < 0.01, ηp2 = 0.02). While the latter two tests were statistically significant, they are to be interpreted as minuscule due to their exceptionally small effect sizes. Figure 1 illustrates the meagerness of these effects.

Figure 1.

Pictorial depiction of target gender by participant gender interaction on feeling thermometer ratings (ηp2 = 0.02).

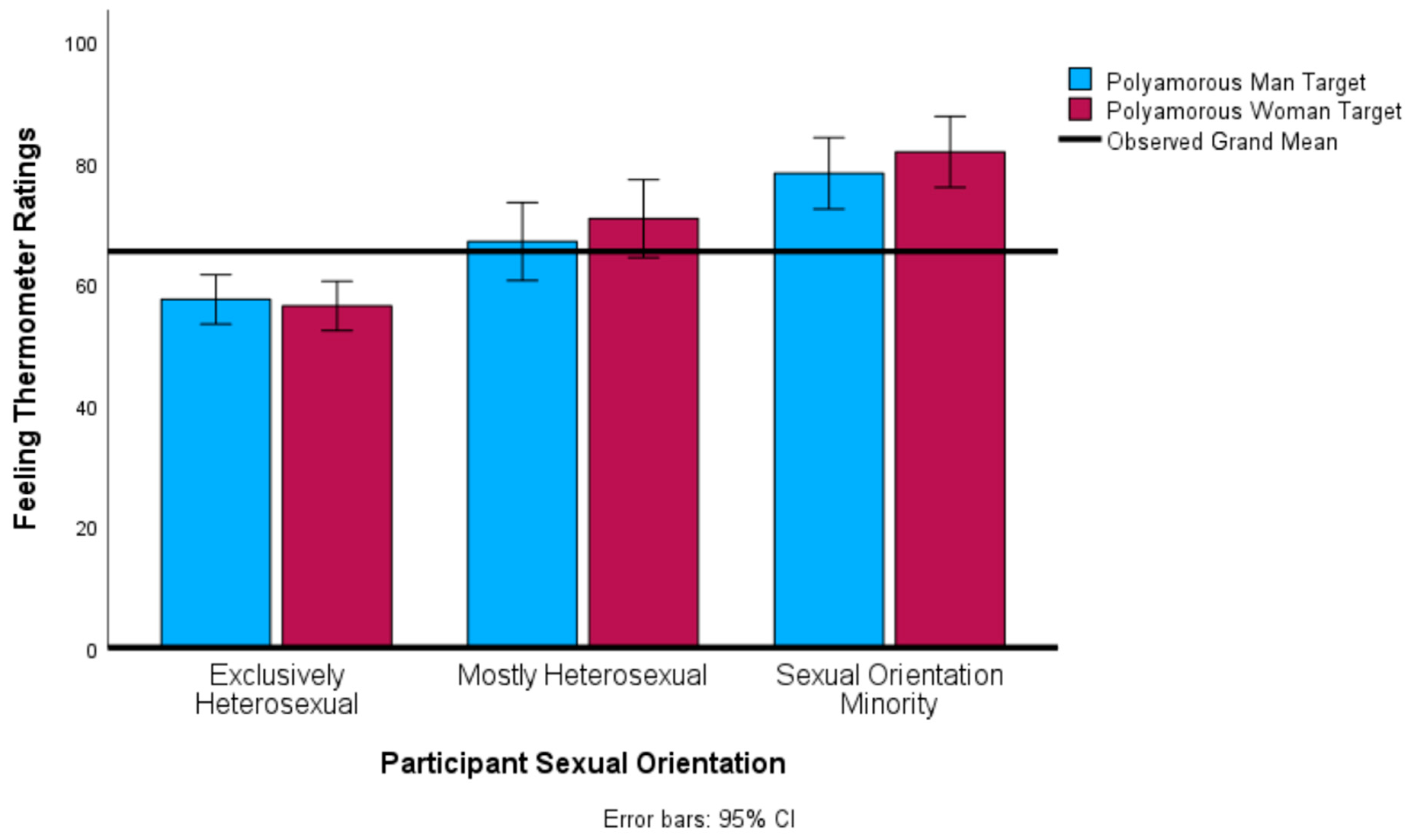

3.1.2. Sexual Orientation and Polyamorous Target Ratings

A second ANOVA was conducted with gender of polyamorous target and participant sexual orientation (i.e., exclusively heterosexual, mostly heterosexual, or sexual orientation minority), where gender of polyamorous target was a repeated-measures variable and participant sexual orientation was a between-subjects’ variable. In this analysis, there was a very weak main effect of polyamorous target gender (F(1,462) = 13.42, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.03). Polyamorous women (M = 65.93, sd = 34.28) were rated slightly more positively than polyamorous men (M = 64.79, sd = 33.75); this is a 1% difference on the 101-point scale and indicates no practical difference. In contrast, there was a larger main effect of participant sexual orientation in relation to feeling thermometers (F(2,462) = 21.57, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.09). This is a medium effect whereby the sexual orientation minority participants (M = 80.02%, sd = 25.62) were more positive in ratings than mostly heterosexual participants (M = 68.88%, sd = 30.87), who, in turn, were more positive than exclusively heterosexual participants (M = 56.90%, sd = 35.28). These main effects were qualified by a weak interaction of polyamorous target gender and participant sexual orientation (F(2,462) = 10.01, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.04). Inspection of Figure 2 indicates that exclusively heterosexual participants rated polyamorous women slightly lower than polyamorous men whereas mostly heterosexual participants and sexual orientation minority participants rated the polyamorous women slightly higher than the polyamorous men.

Figure 2.

Pictorial depiction of target gender by participant sexual orientation interaction on feeling thermometer ratings (ηp2 = 0.04).

3.1.3. Synopsis of Gender and Sexual Orientation Polyamorous Target Rating Findings

In sum, polyamorous targets were rated the same whether they were a polyamorous man or woman, generally. While there were no strong differences in ratings as a function of participant gender (see Figure 1), participant sexual orientation demonstrated a modestly strong effect, with exclusively heterosexual participants rating the targets the least positively. There was a very small interaction such that mostly heterosexual and sexual minority participants favored women polyamorous targets slightly more than men polyamorous targets (see Figure 2).

3.2. Ratings of Dating Likelihood of a Polyamorous Person

3.2.1. Gender Differences in Dating Likelihood of a Polyamorous Partner

Heterosexual women participants’ (n = 270) likelihood of dating a polyamorous man received an average rating of unlikely (M = 1.74, sd = 1.60, with scores ranging from 1 to 8). At the scale anchors, most (74.4%) of these women indicated it was very unlikely that they would date a polyamorous man while only 2.2% indicated that they would be very likely to do so. Heterosexual men participants’ (n = 78) likelihood of willingness to date a polyamorous woman was between unlikely and moderately unlikely (M = 2.54, sd = 2.17). Slightly over half (55.1%) of these men rated their likelihood of dating a polyamorous woman with the lowest likelihood possible (1 = very unlikely) while 5.1% indicated it was very likely (8) that they would date a polyamorous woman. In short, heterosexual women rated their dating a polyamorous partner as more unlikely compared to heterosexual men’s likelihood ratings (t(346) = 3.57, p < 0.001, Hedges’ g = 0.46; this is a moderate effect size). Type of heterosexual made a difference: those who were exclusively heterosexual were more unlikely to date a polyamorous partner than a mostly heterosexual participant (Mexclusively heterosexual = 1.51, sd = 1.35 versus Mmostly heterosexual = 2.09, sd = 1.86, tadjusted(141) = −2.84, p < 0.01, Glass’s Δ = 1.86; this is a large effect size).

3.2.2. Bisexual Women’s Dating Likelihood of a Polyamorous Partner

Bisexual/pansexual/attracted to more than one gender was the most commonly endorsed sexual orientation minority label for women (hereafter, bisexual women, n = 72); ratings of dating likelihood of a polyamorous man (M = 2.43, sd = 2.05) and a polyamorous woman (M = 2.49, sd = 2.06) were the same (t(142) = 0.18, ns, Cohen’s d = 0.03). The average rating was between unlikely and moderately unlikely to date a polyamorous person. Just under half (44.4%) of these bisexual women were very unlikely (1) to date any polyamorous person while 5.6% said that it was very likely (8) that they would date a polyamorous man or woman. Bisexual women, heterosexual women, and heterosexual men were compared on willingness to date a polyamorous partner (F(2,417) = 8.67, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.04); heterosexual women were significantly less likely to be willing to date a polyamorous partner compared to bisexual women and heterosexual men.

3.2.3. Summary of Gender and Orientation Differences in Ratings of Dating Likelihood

In sum, heterosexual men, heterosexual women, and bisexual women rated their dating a polyamorous partner as unlikely. There were gender differences such that heterosexual women were more unlikely to be willing to date a polyamorous partner than heterosexual men. Also, heterosexual women were significantly less likely to be willing to date a polyamorous partner relative to bisexual women. Exclusively heterosexual people were more unlikely than mostly heterosexual people to be willing to date a polyamorous partner.

3.2.4. Relationships between Polyamorous Target and Dating Likelihood Ratings

The relationship between favorability ratings of a polyamorous man and willingness to date a polyamorous man by heterosexual women was quite weak (r(267) = 0.18, p < 0.01). In contrast, the relationship between favorability ratings of a polyamorous woman and willingness to date a polyamorous woman by heterosexual men was moderate (r(78) = 0.40, p < 0.001). These two correlations are marginally significantly different from each other (Fisher’s z = 1.85, p < 0.065). For bisexual women, correlations between ratings of a polyamorous woman/man and willingness to date a polyamorous woman/man were weak, not significant, and mirrored correlations of heterosexual women (i.e., r(69) = 0.21/0.19, ns). In short, positive feelings toward a polyamorous person is a poor predictor of a person being willing to have a romantic relationship with a polyamorous person.

3.3. Relationships of Individual Difference Variables with Polyamory Ratings

3.3.1. Correlations

Generally, bivariate correlations between the individual difference measures and the polyamorous targets were consistently equal in strength, ranging in absolute value from 0.15 to 0.47 and were quite similar for polyamorous men and polyamorous women targets (see Table 1). These are in contrast to the correlations of the personality dispositions with polyamorous target dating likelihood; some of these correlations were negligible and some were modestly strong, with the patterns of correlations differing for polyamorous men and women dating targets.

In order to explore the relationships between the individual differences and the ratings of polyamory further, a series of multiple regression analyses were conducted whereby the individual difference measures (i.e., authoritarianism, erotophobia–erotophilia, hostile and benevolent sexism, social dominance orientation, intergroup disgust sensitivity, sociosexuality, and religiosity) were multiply regressed upon the polyamory dependent measures. For the two feeling thermometers, participant gender and participant sexual orientation were also included as predictor variables.

3.3.2. Polyamorous Target Feeling Thermometers Multiple Regression

Multiple regression analyses were conducted with the feeling thermometers for polyamorous men and polyamorous women targets as dependent variables. The individual difference variables, along with participant gender and sexual orientation, were the predictor variables. Both multiple regression equations were significant, with Multiple Rs of 0.48 and 0.54 for polyamorous men and women targets, respectively. Inspection of the first two columns of Table 2 demonstrates a nearly identical pattern of prediction of the targets, with authoritarianism and erotophobia–erotophilia being the strongest and most significant personality predictors of target ratings. Participant sexual orientation was significant for ratings of polyamorous women and marginally significant for ratings of polyamorous men. Because of these similarities, we re-conducted the multiple regression using an average of the two polyamorous target feeling thermometers; the prediction equation was significant, with a Multiple R of 0.51. Three significant variables accounted for a quarter of the variance in feeling thermometer ratings: authoritarianism (β = −0.21), erotophobia–erotophilia (β = −0.16), and participant sexual orientation (β = 0.10). Those who exhibited low authoritarianism and were more comfortable with sexuality, and those who were a sexual orientation minority were the most likely to rate the polyamorous targets most positively.

Table 2.

Multiple regressions: individual difference variables as predictors of polyamory target ratings.

3.3.3. Polyamorous Target Dating Likelihood Multiple Regression

Dating likelihood in relation to a polyamorous man was the dependent variable, with personality constructs, along with participant sexual orientation (exclusively or mostly heterosexual), as predictor variables for the heterosexual women participants. The prediction equation was significant but the multiple correlation was relatively small (R = 0.36). The predictors of the likelihood of dating a polyamorous man included sociosexuality (β = 0.18) and hostile sexism (β = 0.18) as significant while erotophobia–erotophilia (β = 0.15) and benevolent sexism (β = −0.14) were marginally significant variables. Those with greater sociosexual orientation (i.e., more likely to have engaged in uncommitted sexuality as well as have positive attitudes toward and fantasies of casual, uncommitted sexuality) and those with greater hostile sexism (i.e., classic, overt sexist positions, but see note b of Table 2) rated their dating likelihood higher. Erotophobia–erotophilia approached statistical significance such that those women who exhibited a more positive approach-to-sexuality disposition were more likely to be willing to date a polyamorous man. Similarly, benevolent sexism approached significance such that women who rejected benevolent sexism the most strongly were more willing to date a polyamorous man.

In relation to willingness to date a polyamorous woman, the regression equation was significant (R = 0.53) but none of the coefficients achieved significance. This is likely because the variable-to-participant ratio was too high (nine variables with only 70 heterosexual men participants). Examination of the non-significant beta coefficients suggest that authoritarianism (β = −0.21) and erotophobia–erotophilia (β = 0.17) were similar to those predictors for the feeling thermometers. Also exhibiting relatively high, but non-significant beta coefficients were religiosity (β = −0.20) and social dominance orientation (β = 0.17).

Heterosexual men and women’s ratings of an other-sex target were combined to produce a likelihood of dating a polyamorous partner and the multiple regression was re-conducted using the individual difference measures and participant sexual orientation (exclusively or mostly heterosexual), as well as participant gender (man or woman). The multiple regression equation was significant and produced a Multiple R of 0.40. Significant in the equation were participant gender (β = −0.16), benevolent sexism (β = −0.16), sociosexuality (β = 0.16), and erotophobia–erotophilia (β = 0.14). Authoritarianism was marginally significant (β = −0.15). Willingness to date a polyamorous partner increased when the participant was a man, rejected benevolent sexism (i.e., covert, insidious sexism where adherence to traditional gender roles appears positive but is patronizing), had a greater sociosexual orientation (e.g., more favorable attitudes and fantasies toward uncommitted, casual sex), and had greater erotophilia (e.g., more comfortable with sexuality). Lower authoritarianism resulting in a greater likelihood to date a polyamorous person also added to the explanation of variance, but marginally.

Because there was about the same number of bisexual/pansexual women as heterosexual men (Ns = 67 vs. 70), the multiple regression analyses were repeated for bisexual women with regard to dating a polyamorous man and then a polyamorous woman. The equation was significant for dating a polyamorous woman, with a Multiple R of 0.47, but accounted for very little variance (R2adjusted = 0.13); only sociosexuality was significant (β = 0.30), while intergroup disgust sensitivity (β = 0.24) and social dominance orientation (β = 0.16) had substantial but insignificant beta coefficients. While the equation for these bisexual women participants for dating a polyamorous man was marginally significant (p = 0.056), a very similar pattern of beta coefficients was produced: sociosexuality (β = 0.27), intergroup disgust sensitivity (β = 0.23), and social dominance orientation (β = 0.11) were substantive yet insignificant predictor variables. The last five columns of Table 2 contain the full statistics associated with dating likelihood multiple regression analyses.

3.3.4. Synopsis of Individual Differences as Multiple Regression Predictors of Polyamory Ratings

Authoritarianism and erotophobia–erotophilia, as individual difference variables, were significant and substantial predictors of feeling thermometer ratings of polyamorous targets. Participant sexual orientation also predicted feelings about polyamorous targets. The three variables accounted for about a quarter of the variance in feelings toward polyamorous targets, consistently. In contrast, the individual difference variables were neither strong nor consistent predictors of willingness to date a polyamorous person. Although heterosexual men and heterosexual women evidenced somewhat similar regression coefficients, men’s dating likelihood of a polyamorous woman was most strongly predicted by authoritarianism while heterosexual women’s dating likelihood of a polyamorous man was most strongly predicted by sexuality-based variables (i.e., hostile and benevolent sexism, sociosexuality, and erotophobia–erotophilia). In contrast to heterosexual participants, bisexual women’s dating likelihood was predicted by intergroup disgust sensitivity as well as sociosexuality. However, because of the small n, the multiple regression analyses for men and bisexual women participants should be viewed with caution. In short, liking a polyamorous person and being willing to date a polyamorous person are two very different constructs that have distinctively different individual difference predictors depending on the gender and sexual orientation of the social perceiver (i.e., the potential dater).

4. Discussion

Ratings on the feeling thermometer, overall, were tepid: they were slightly above the midpoint on the scale. However, these were significantly lower when compared to sexual orientation and gender identity targets [58]. Definitively, participants in this study were generally not willing to date a polyamorous partner. This illustrates the importance of how one measures attitudes: when it involves the self (i.e., the social distance of an intimate, dating relationship), people may be more negative than when simply assessing an outgroup member. Of course, both of these types of ratings are prone to self-presentation and social desirability bias inherent in explicit measures of attitudes [29]. Further, explicit measures likely reflect much conscious, cognitive processing relative to automated attitudinal responses to outgroups. For example, Thompson and colleagues [18] found that explicit attitudes toward CNM concepts (e.g., group sex, open marriage) correlated weakly with an implicit attitude assessment (r = 0.18; see also [29,34,59] for weak correlations between implicit and explicit polyamory attitudes). Implicit attitudes are thought to represent attitudes internalized through culture and society regarding the attitude object. However, the findings of the current study do illustrate that liking of a polyamorous target (i.e., via feeling thermometers) did not necessarily predict anticipated behavior relating to the polyamorous person (i.e., dating likelihood).

Alternatively, the weak relationships between ratings of a polyamorous individual and willingness to date a polyamorous partner could be considered in the context of the variability in attitude–behavior correspondence that has been found generally [60]. There are different conditions that affect the attitude–behavior relationship (e.g., attitude stability, attitude accessibility) depending on context [60]. Behavioral intention is often treated as a proxy for actual behavior [14]. If willingness to date a polyamorous partner is considered as an expression of a behavioral intention, then the correspondence between liking a polyamorous person and dating a polyamorous person may be weak (i.e., correlations of 0.19, 0.21, and 0.40) given the context of the generally tepid, mid-range attitudes toward polyamorous persons (see Figure 1). Specifically, Bechler and colleagues [61] found that neutral attitudes (i.e., at the scale mid-point, slightly positive, or slightly negative) demonstrated weak attitude–behavior relationships relative to the attitude–behavior correspondence for attitudes that were of strong valence (i.e., very positive or very negative). This explanation is speculative and must be tested with an actual behavior measure. Regardless, a firm conclusion is that the two dependent measures—ratings of a polyamorous target and willingness to date a polyamorous person—were weakly correlated and predicted by different individual difference constructs.

4.1. Demographic Predictors of Polyamory Ratings

Although a weak effect, women rated polyamorous targets more positively than men did. However, when the rating had implications for the self in terms of being willing to date a polyamorous partner, heterosexual women rated a potential polyamorous man partner more negatively than heterosexual men rated a potential polyamorous woman partner. This illustrates that gender-of-perceiver differences may exist depending on how the polyamorous attitude variable is measured. Different attitude outcome measurement might account for some of the equivocal gender differences found in the existing literature [16,21,26,27,29,31,35,36,37,38] versus [13,18,24,33,39,40].

Participant sexual orientation demonstrated modest effects in ratings of polyamorous targets; this was consistent with prior research [23,28,31,33,35,39] on explicit measures of polyamory attitudes, which has found that sexual orientation and gender identity minority participants rate polyamorous targets the most favorably. Further finessing this sexual orientation finding, the results demonstrate that “heterosexuals”, as a group, are not all equal. Those who rated themselves as mostly heterosexual were significantly more positive than exclusively heterosexual participants. Studies failing to separate these types of heterosexuals may be obscuring the effects of the unique, more sexually fluid group of mostly heterosexuals [62].

When assessing polyamorous persons separated by gender, women and men targets were rated practically the same. Thompson et al. [24] conducted one of the few experiments that examined the gender of the CNM person being evaluated (swinging, polyamory, open relationship, role-playing scenarios) and found that women CNM instigators were judged more favorably than men CNM instigators. We support this gender difference somewhat when considering the interaction of target gender and sexual orientation of the participant. For those who were exclusively heterosexual, gender of polyamorous target was irrelevant but, for sexual orientation minority and mostly heterosexual participants, woman polyamory targets were rated more favorably.

Considering these findings from an intergroup threat theory perspective, the concept of polyamory is likely both a realistic and symbolic psychological threat, especially to exclusively heterosexuals. Heterosexuals, particularly those with increasing conservative political orientation, are much more negative toward polyamorous marriage than sexual minority individuals [40]. It is feasible that exclusively heterosexuals are more conservative, generally, than mostly heterosexual and sexual orientation minority people. Polyamory, as a construct, may be viewed as a threat to traditional marriage and family, upon which society is predicated, as well as threatening to the social order and societal stability that marriage provides [63]. In social dominance terms, exclusively heterosexual people are likely at the top of this hierarchy. Polyamory may also threaten exclusively heterosexual people in terms of their sexuality; Cunningham et al. [35] identified same-sex intimacy as well as sexual health risk concerns as distinct subscales on their CNM Apprehension scale, derived from participant-generated reasons for rejecting CNM participation. Anxiety or apprehension of interacting with an outgroup is a form of realistic threat within the intergroup threat theory [49].

In short, gender of the target, participant gender, and sexual orientation of the perceiver should be examined in future research to tease apart the effects these elements have on attitudes. Furthermore, the type of attitude assessment must be selected with care as the type of outcome measure also seems to influence the findings. Some current existing measures conflate outgroup items with self-reference items (Moors et al.’s scale is an example of this [64]).

4.2. Personality Predictors of Polyamory Ratings

The second goal of the current study was to explore individual difference variables as predictors of polyamory attitude from the intergroup threat theory framework [48,49], where constructs such as authoritarianism, social dominance, sexism, and intergroup disgust sensitivity were used as personality dispositions that could produce or reflect threat responses to polyamory. In addition, sexuality-related perceiver attributes, in the form of erotophobia–erotophilia and sociosexual orientation, were included. Correlations of these individual differences suggest that all had small-to-modest relationships with feelings about polyamorous men and women. The relationships were less uniform for dating likelihood, where heterosexual women showed no relationship between polyamorous man dating likelihood for authoritarianism nor hostile sexism. In contrast, heterosexual men showed no relationship between likelihood of dating a polyamorous woman and social dominance orientation nor intergroup disgust sensitivity. Erotophobia–erotophilia (modestly strong), benevolent sexism (modestly strong), sociosexuality (weakly), and religiosity (very weakly) demonstrated general consistency across relationships with the different polyamorous ratings.

The multiple regression analyses for polyamorous feeling thermometers told a consistent story: feeling thermometer ratings were predicted by authoritarianism, erotophobia–erotophilia, and participant sexual orientation. Those who were least right-wing authoritarian, most erotophilic, and not exclusively heterosexual were the most favorable, regardless of polyamorous target gender. These three variables accounted for about a quarter of the variance in feeling thermometer ratings. These findings are consistent with an intergroup threat theory analysis [49] such that polyamorous persons likely threaten traditional values (e.g., society is built on familial relationships of man plus woman), produce defensive aggression toward outgroups (e.g., polyamorous persons are not of my monogamous, couple-oriented tribe), and contradict deference to authority (e.g., polyamorous people are not following the rules set by our leaders—society does not sanction legal intimate relationships beyond the monogamous couple) inherent in the right-wing authoritarianism scale [65]. The judgement process of polyamorous targets seems the same for men and women participants; when rating a polyamorous outgroup member, gender (of participant and of target) was irrelevant to the equation.

Noteworthy is the fact that erotophobia–erotophilia predicted feelings about polyamorous targets above and beyond authoritarianism; that is, feelings about sexuality were uniquely relevant to feelings about a person who engages in atypical, often stigmatized sexual behavior. Balzarini et al. [66] found that erotophobia–erotophilia, sociosexual orientation, and sexual permissiveness were significantly different between people in monogamous relationships compared with people in various CNM relationships. Sexuality dispositions are obviously relevant to feelings about and actions regarding polyamory and CNM.

Unlike feeling thermometer ratings of a polyamorous person, ratings of likelihood of dating a polyamorous partner did not produce consistent predictors across participant groups (i.e., heterosexual men, heterosexual women, and bisexual women). Consistently, more conservative beliefs were predictive of less willingness to date a polyamorous individual; however, the specific conservative measure changed across participants gender and sexual orientation. For example, social dominance orientation and authoritarianism were predictive for heterosexual men while intergroup disgust sensitivity and sociosexuality were predictive for bisexual women. Such findings indicate that there might be factors at play other than what was measured here or that threat-relevant motivational factors differ depending on demographic group membership.

Perhaps the self-relevance of dating a polyamorous person differs by social perceiver gender and sexual orientation. When investigating how young people would respond to a request for a CNM relationship, Sizemore and Olmstead [67] identified themes unique to women, for example. Or perhaps, as indicated by the small Adjusted R2 value, other variables not included in this study would be more consistent predictors of likeliness to date a polyamorous person. With good theoretical reasoning, attachment style, for example, shows promise as a predictor of CNM participation willingness [46,64,66]. Perhaps inconsistency of polyamory with relationship style would evoke greater relationship conflict apprehension [35] and threat, and thus would produce stronger findings vis-à-vis willingness to date a polyamorous partner. This is an area for future investigation.

Sociosexuality was modestly predictive of polyamorous partner dating likelihood for all participants, although most strongly for bisexual women. This is consistent with other research, which has found sociosexuality to be predictive of CNM attitudes [31,46]. Erotophobia–erotophilia was also a consistent, albeit weak, predictor of polyamory partner dating likelihood. Discomfort with sexuality and sociosexual restrictiveness are not necessarily part of authoritarianism per se, but sexual inhibition was originally included in the definition of the authoritarian personality [65]. These constructs might represent sexual conservatism, with sociosexuality being particularly oriented toward one’s own sexuality. Sociosexual orientation and erotophobia–erotophilia, while dispositional, may reflect relationship styles, sexual mores, and marriage and family values (i.e., sexual and relational conservatism–liberalism). As such, these constructs may be sensitive to or reflective of a different type of threat relative to the more general personality dispositions like authoritarianism and social dominance. While we interpret the polyamorous attitude predictiveness of these personality and individual difference variables within intergroup threat theory, we have not assessed through which type of threats (i.e., realistic or symbolic, group or individual) these personal characteristics influence so as to affect attitudes toward and willingness to engage with polyamorous people.

The findings of the current research must be considered with the limitations of the study design; this investigation was correlational so causation cannot be inferred. The results are interpreted within and consistent with the intergroup threat theory framework [48,49] but are not definitive proof of this theory. The outcome measures used herein are limited: evaluative and normative beliefs underlying attitudes were not assessed, nor were semantic differential nor specific intention scales [14]. A more robust assessment would include an implicit attitudes assessment with self-presentation bias considered [29]. The use of a student sample may have produced different attitudes than if a sample drawn from the general public had been obtained [68]. Using World Values Survey data, Hanel and Vione [68] found that student samples did not differ in variance compared to general population samples, including on a seven-item measure of personal–sexual moral issues (i.e., an attitude measure involving how justified such behaviors/issues as homosexuality and abortion were rated). However, in countries higher in intellectual autonomy, students did appear to have more heterogeneity of variance in relation to median scores. Thus, the findings in this study probably do not reflect what would be found had a general population sample be used. Regardless, this study can be considered an exploratory investigation into individual difference predictors of attitudes toward polyamory, which adds to the burgeoning literature on attitudes toward polyamory and CNM.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that attitudes toward polyamorous outgroups can be quite different from attitudes toward being personally involved with a polyamorous target. When the relational and sexual self was implicated, perceiver gender and sexual orientation differences resulted and attitudes were rather negative. Personal dispositions—specifically, right-wing authoritarianism and erotophobia–erotophilia—were consistent predictors of polyamorous outgroup targets but were not quite so consistently predictive of the likelihood of dating a polyamorous partner. For polyamorous partner dating likelihood, sociosexual orientation was a stronger, more consistent predictor. These findings illustrate that, when measuring attitudes toward polyamory, it is critical to consider whether or not the assessment has direct implications for the perceiver’s self.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.J.R. and R.G.; methodology, B.J.R. and R.G.; data entry: R.G.; formal analysis, B.J.R.; writing—original draft preparation, B.J.R.; writing—review and editing, B.J.R. and R.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. Part of this work was supported by St. Jerome’s University under faculty research grant IRG430.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved on 20 September 2021 by the Office of Research Ethics of the University of Waterloo (Protocol code 43494) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Participants of this study were not asked for permission for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data are not available.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Dr. Cori Enright for comments on an earlier draft.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Barker, M. This is my partner, and this is my… partner’s partner: Constructing a polyamorous identity in a monogamous world. J. Constr. Psychol. 2005, 18, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moors, A.C.; Ramos, A.; Schechinger, H. Bridging the science communication gap: The development of a fact sheet for clinicians and researchers about consensually non-monogamous relationships. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2021; Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubel, A.N.; Burleigh, T.J. Counting polyamorists who count: Prevalence and definitions of an under-researched form of consensual nonmonogamy. Sexualities 2020, 23, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheff, E. Polyamory is deviant—But not for the reasons you may think. Deviant Behav. 2020, 41, 882–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herek, G.M. Confronting sexual stigma and prejudice: Theory and practice. J. Soc. Issues 2007, 63, 905–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, T.D.; Moors, A.C.; Matsick, J.L.; Ziegler, A. The fewer the merrier? Assessing stigma surrounding consensually non-monogamous romantic relationships. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 2013, 13, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, D.; Fasoli, F.; Huic, A.; Lopes, D. Which partners are more human? Monogamy matters more than sexual orientation for dehumanization in three European countries. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2018, 15, 504–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Castro, Y.; García Manso, A.; Martínez-Román, R.; Aguiar-Fernández, F.X.; Peixoto Caldas, J.M. Analysis of the experiences of polyamorists in Spain. Sex. Cult. 2022, 26, 1659–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Séguin, L.J. The good, the bad, and the ugly: Lay attitudes and perceptions of polyamory. Sexualities 2019, 22, 669–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, M.D.; Jones, P.; Taylor, B.A.; Roush, J. Healthcare experiences and needs of consensually nonmonogamous people: Results from a focus group study. J. Sex. Med. 2019, 16, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moors, A.C.; Gesselman, A.N.; Garcia, J.R. Desire, familiarity, and engagement in polyamory: Results from a national sample of single adults in the United States. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 619640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsick, J.L.; Conley, T.D.; Ziegler, A.; Moors, A.C.; Rubin, J.D. Love and sex: Polyamorous relationships are perceived more favourably than swinging and open relationships. Psychol. Sex. 2014, 5, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cragun, R.T.; Sumerau, J.E. The last bastion of sexual and gender prejudice? Sexualities, race, gender, religiosity, and spirituality in the examination of prejudice toward sexual and gender minorities. J. Sex Res. 2015, 52, 821–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, M. The social psychology of intergroup relations: Social categorization, ingroup bias, and outgroup prejudice. In Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles, 2nd ed.; Kruglanski, A.W., Higgins, E.T., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 695–715. [Google Scholar]

- Burris, C.T. Torn between two lovers? Lay perceptions of polyamorous individuals. Psychol. Sex. 2013, 5, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, D.L.; Lopes, D.; Huic, A. What drives the dehumanization of consensual non-monogamous partners? Arch. Sex. Behav. 2021, 50, 1587–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.E.; Moore, E.A.; Haedtke, K.; Karst, A.T. Assessing implicit associations with consensual non-monogamy among US early emerging adults: An application of the single-target implicit association test. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2020, 49, 2813–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, D.L.; Aybar Camposano, G.A.; Lopes, D. Stigmatization of consensual non-monogamous partners: Perceived endorsement of conservation or openness to change values vary according to personal attitudes. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2022, 51, 3931–3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzarini, R.N.; Shumlich, E.J.; Kohut, T.; Campbell, L. Dimming the “Halo” around monogamy: Re-assessing stigma surrounding consensually non-monogamous romantic relationships as a function of personal relationship orientation. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, M.T. The perceived satisfaction derived from various relationship configurations. J. Relatsh. Res. 2016, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunt-Mejer, K.; Campbell, C. Around consensual nonmonogamies: Assessing attitudes toward nonexclusive relationships. J. Sex Res. 2016, 53, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burleigh, T.J.; Rubel, A.N.; Meegan, D.V. Wanting ‘the whole loaf’: Zero-sum thinking about love is associated with prejudice against consensual nonmonogamists. Psychol. Sex. 2017, 8, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.E.; Hart, J.; Stefaniak, S.; Harvey, C. Exploring heterosexual adults’ endorsement of the sexual double standard among initiators of consensually nonmonogamous relationship behaviors. Sex Roles 2018, 79, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunt-Mejer, K.; Łyś, A.E. They must be sick: Consensual nonmonogamy through the eyes of psychotherapists. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2019, 37, 58–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutzler, K.T.; Giuliano, T.A.; Herselman, J.R.; Johnson, S.M. Three’s a crowd: Public awareness and (mis)perceptions of polyamory. Psychol. Sex. 2016, 7, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.M.; Giuliano, T.A.; Herselman, J.R.; Hutzler, K.T. Development of a brief measure of attitudes towards polyamory. Psychol. Sex. 2015, 6, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flicker, S.M.; Sancier-Barbosa, F. Your happiness is my happiness: Predicting positive feelings for a partner’s consensual extra-dyadic intimate relations. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2024, 53, 941–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.E.; Bagley, A.J.; Moore, E.A. Young men and women’s implicit attitudes towards consensually nonmonogamous relationships. Psychol. Sex. 2018, 9, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, D.; Pascoal, P.M.; Rosa, P.J. Facing polyamorous lives: Translation and validation of the attitudes towards polyamory scale in a Portuguese sample. Sex. Relatsh. Ther. 2020, 35, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.; Wilson, K. Development of the Consensual Non-Monogamy Attitude Scale (CNAS). Sex. Cult. 2017, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, R.A.; Burckley, J.; Centelles, V. Sanctioning sex work: Examining generational differences and attitudinal correlates in policy preferences for legalization. J. Sex Res. 2023, 60, 903–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St Vil, N.M.; Giles, K.N. Attitudes toward and willingness to Engage in Consensual Non-Monogamy (CNM) among African Americans who have never engaged in CNM. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2022, 51, 1823–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenyon, C.R.; Wolfs, K.; Osbak, K.; van Lankveld, J.; Van Hal, G. Implicit attitudes to sexual partner concurrency vary by sexual orientation but not by gender—A cross sectional study of Belgian students. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, N.C.; Mitchell, R.C.; Mogilski, J. Which styles of moral reasoning predict apprehension toward consensual non-monogamy? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2022, 196, 11173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, M.P.; Hendrick, S.S. Therapists’ sexual values for self and clients:Implications for practice and training. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2003, 34, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoropoulos, I.; Daoultzis, K.-C.; Kordoutis, P. Identifying context-related socio-cultural predictors of negative attitudes toward polyamory. Sex. Cult. 2023, 27, 1264–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, G.; Park, Y.; Hayes, A.; Grosdidier, I.V.; Park, S.W. Quality of alternatives positively associated with interest in opening up a relationship. Pers. Relatsh. 2021, 28, 538–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.-T.; Chen, C.-Y.; Chu, C.-H.; Kuan, Y.-S.; Chang, S.-Y.; Chi, P.-R. Public attitude toward multiple intimate relationships among unmarried young adults in Taiwan. Arch. Guid. Couns. 2019, 41, 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, G.; Aiello, A.; Ellis, C.; Compton, D. Attitudes toward same-sex marriage, polyamorous marriage, and conventional marriage ideals among college students in the southeastern United States. Sex. Cult. 2022, 26, 1599–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, H.A.; Warner, R.H.; Broussard, K.A.; Harton, H.C. Predictors of transgender prejudice: A meta-analysis. Sex Roles 2022, 87, 583–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckitt, J. Introduction to the special section on authoritarianism in societal context: The role of threat. Int. J. Psychol. 2013, 48, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetherington, M.J.; Weiler, J.D. Authoritarianism and Polarization in American Politics; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Moors, A.C.; Selterman, D.F.; Conley, T. Personality correlates of desire to engage in consensual non-monogamy among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. J. Bisexuality 2017, 17, 418–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penke, L.; Asendorpf, J.B. Beyond global sociosexual orientations: A more differentiated look at sociosexuality and its effects on courtship and romantic relationships. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 95, 1113–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ka, W.S.L.; Bottcher, S.; Walker, B.R. Attitudes toward consensual non-monogamy predicted by sociosexual behavior and avoidant attachment. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 41, 4312–4320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rye, B.J.; Goldszmidt, R. Do attitude functions and perceiver demographics predict attitudes toward asexuality? Psychol. Sex. 2023, 14, 572–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croucher, S.M. Integrated threat theory. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, W.G.; Ybarra, O.; Rios, K. Intergroup threat theory. In Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination; Nelson, T.D., Ed.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 255–278. [Google Scholar]

- Rye, B.J.; Underhill, A. Contraceptive context, conservatism, sexual liberalism, and gender-role attitudes as predictors of abortion attitudes. Women’s Reprod. Health 2019, 6, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altemeyer, B. Right-Wing Authoritarianism; University of Manitoba Press: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, A.K.; Sidanius, J.; Kteily, N.; Sheehy-Skeffington, J.; Pratto, F.; Henkel, K.E.; Foels, R.; Stewart, A.L. The nature of social dominance orientation: Theorizing and measuring preferences for intergroup inequality using the new SDO7 scale. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 109, 1003–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidanius, J.; Pratto, F. Social Dominance: An Intergroup Theory of Social Hierarchy and Oppression; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Glick, P.; Fiske, S.T. Ambivalent sexism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 33, 115–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rye, B.J.; Fisher, W.A. Sexual Opinion Survey. In Handbook of Sexuality-Related Measures, 4th ed.; Milhausen, R.R., Sakaluk, J.K., Fisher, T.D., Davis, C.M., Yarber, W.L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 570–572. [Google Scholar]

- Penke, L. Revised Sociosexual Orientation Inventory. In Handbook of Sexuality-Related Measures, 4th ed.; Milhausen, R.R., Sakaluk, J.K., Fisher, T.D., Davis, C.M., Yarber, W.L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 685–688. [Google Scholar]

- Hodson, G.; Choma, B.L.; Boisvert, J.; Hafer, C.L.; MacInnis, C.C.; Costello, K. The role of intergroup disgust in predicting negative outgroup evaluations. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 49, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rye, B.J.; Goldzsmidt, R. It’s More Me than You: A Comparative Analysis of Attitudes towards Sexuality and Gender Minority People; St. Jerome’s University: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2024; manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Gouveia, V.V.; Mendes, L.A.C.; Freire, S.E.A.; Freires, L.A.; Barbosa, L.H.G.M. Medindo Associação Implícita com o FreeIAT em Português: Um exemplo com atitudes implícitas frente ao poliamor. Psychol./Psicol. Refl. Exão E Crítica 2014, 27, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Glasman, L.R.; Albarracín, D. Forming attitudes that predict future behavior: A meta-analysis of the attitude-behavior relation. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 132, 778–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechler, C.J.; Tormala, Z.L.; Rucker, D.D. The attitude-behavior relationship revisited. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 32, 1285–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savin-Williams, R.C. An exploratory study of exclusively heterosexual, primarily heterosexual, and mostly heterosexual young men. Sexualities 2018, 21, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, W. Introduction to Sociology—3nd Canadian Edition; BCcampus Open Education: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2023; Available online: https://opentextbc.ca/introductiontosociology3rdedition (accessed on 16 July 2024).

- Moors, A.C.; Conley, T.D.; Edelstein, R.S.; Chopik, W.J. Attached to monogamy? Avoidance predicts willingness to engage (but not actual engagement) in consensual non-monogamy. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2015, 32, 222–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B.A.; Ngo, J. The Right-Wing Authoritarianism Scale. In Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences; Zeigler-Hill, V., Shackelford, T., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzarini, R.N.; Shumlich, E.J.; Kohut, T.; Campbell, L. Sexual attitudes, erotophobia, and sociosexual orientation differ based on relationship orientation. J. Sex Res. 2020, 57, 458–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sizemore, K.M.; Olmstead, S.B. Willingness of emerging adults to engage in consensual non-monogamy: A mixed-methods analysis. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2018, 47, 1423–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanel, P.H.P.; Vione, K.C. Do student samples provide an accurate estimate of the general public? PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0168354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).