Sexting Motivation Scale (EMS) in Peruvian Youth

Abstract

1. Introduction

Conceptual Delimitation of Motivation for Sexting

2. Methodology

2.1. Methodological Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Instruments

Sexting Motivation Scale (EMS)

2.4. Procedure and Ethical Considerations

- The first section explained the purpose of the research and presented the informed consent form, giving the participants the freedom to choose whether to participate. If the participant chose not to participate, the questionnaire was automated to skip all questions.

- The second part asked participants to provide information about sociodemographic data, with different mandatory questions for the research. Participants were not required to reveal their identities to guarantee anonymity.

- The third and final section detailed the questions with the appropriate response options.

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Content Validity

3.2. Descriptive Analysis of Items

3.3. Exploratory Factor Analysis

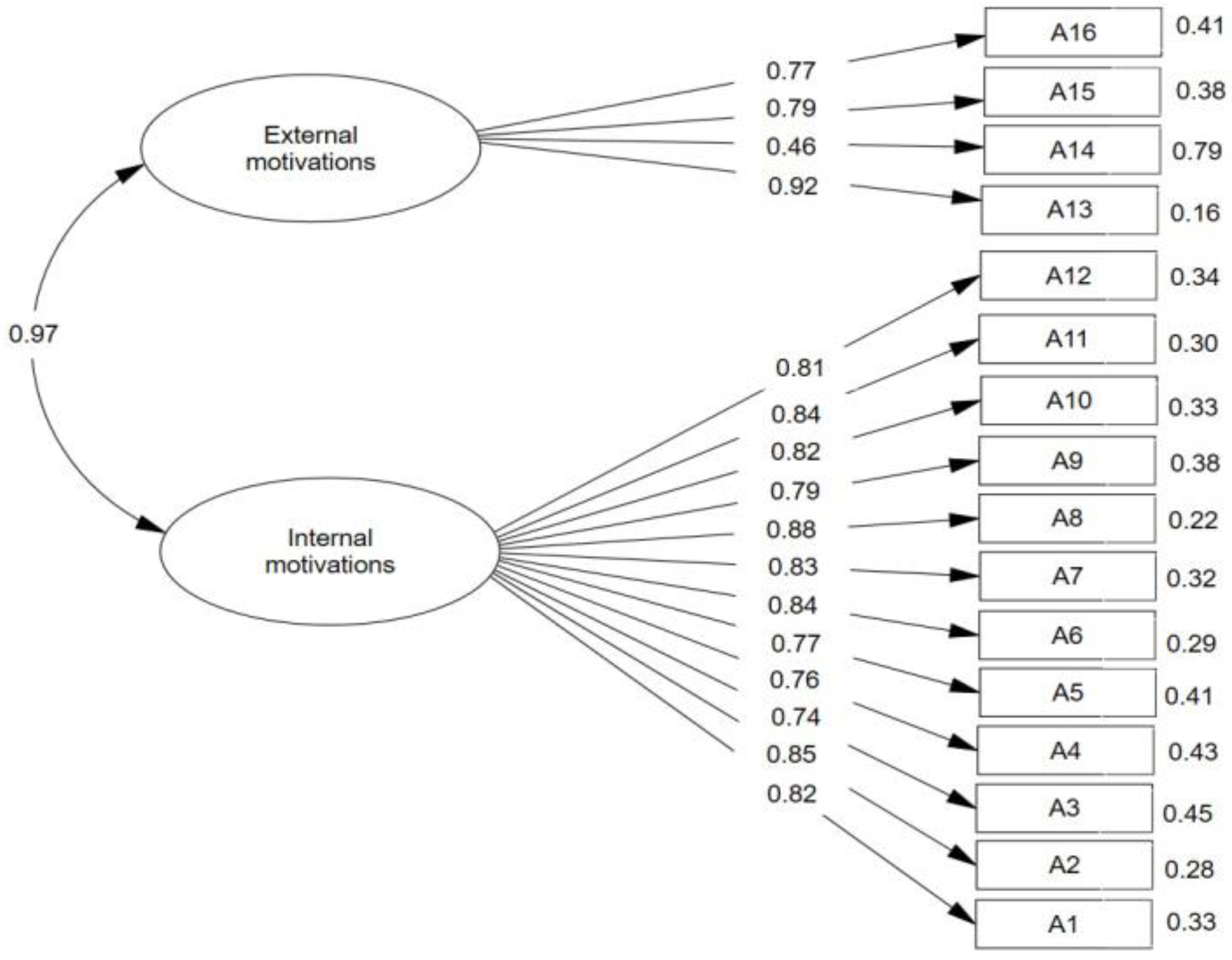

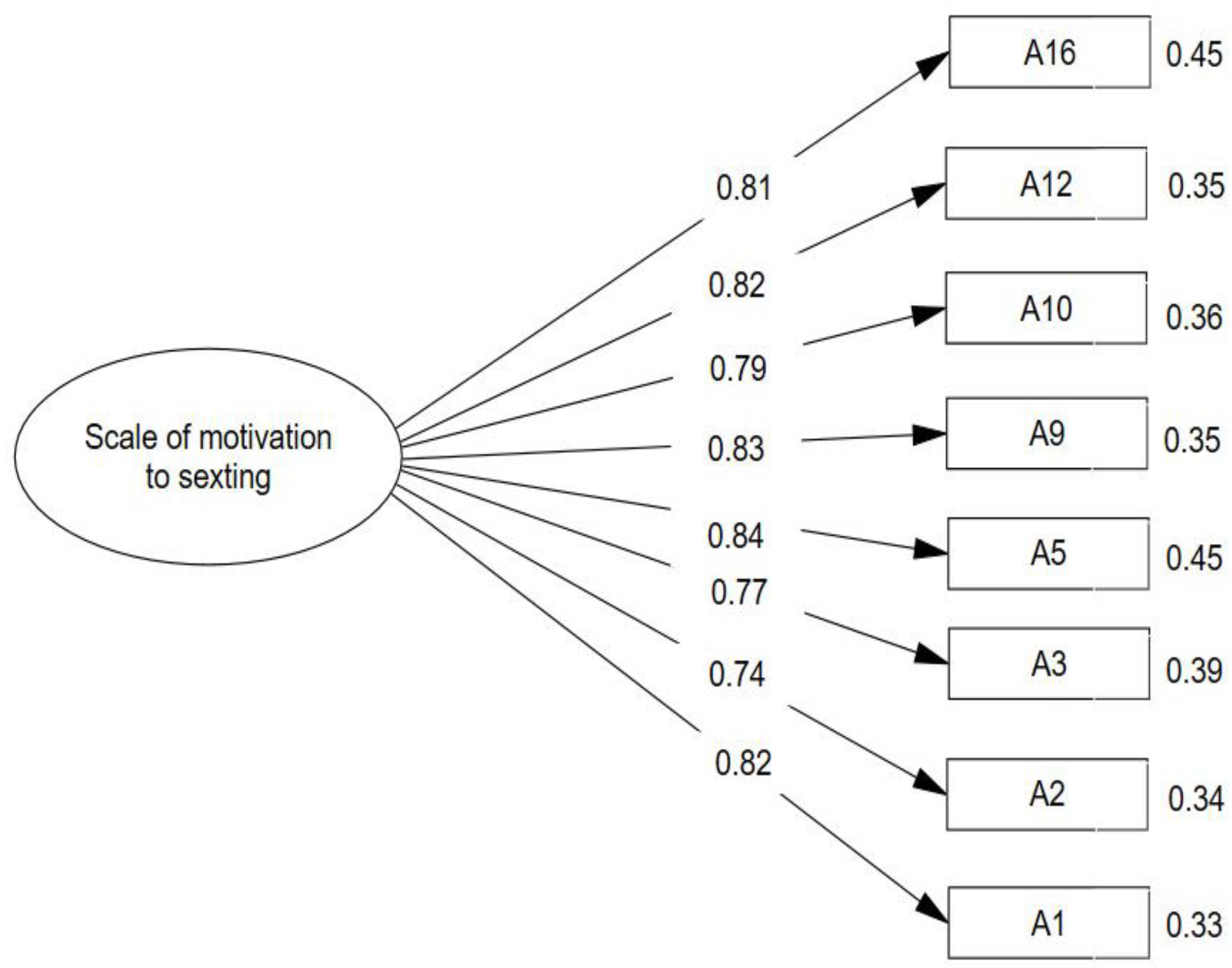

3.4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Invariance

3.5. Scale (EMS)

3.6. Reliability

4. Discussions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Data Collection Instruments

Sexting Motivation Scale (EMS)

| No. | Description | Answers | ||||

| Indicator | Many Times | Sometimes | Hardly Ever | Never | ||

| 1 | I practice sexting to feel valuable | Internal | ||||

| 2 | I sext because I want to keep up with those around me | External | ||||

| 3 | Practicing sexting makes me feel more confident about myself | Internal | ||||

| 4 | I am afraid my partner will leave me, so I send him/her sexy photos. | External | ||||

| 5 | I send provocative images whenever I feel anxious and tense | Internal | ||||

| 6 | I sent images of sexual content on nights when I could not sleep | External | ||||

| 7 | I send sexy images (packs) to my partner to prevent him/her from thinking that I do not trust him/her | Internal | ||||

| 8 | I practice sexting to fit into a social group | Internal | ||||

References

- Venegas-Vera, A.; Colbert, G.; Lerma, E. Positive and negative impact of social media in the COVID-19 era. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 21, 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, N.; Emsley, R.; Lobban, F.; Bucci, S. Social media and its relationship with mood, self-esteem and paranoia in psychosis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2018, 138, 558–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szlyk, H.S.; Li, X.; Kasson, E.; Peoples, J.E.; Montayne, M.; Kaiser, N.; Cavazos-Rehg, P. How do teens with a history of suicidal behavior and self-harm interact with social media? J. Adolesc. 2023, 95, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Kattapuram, T.; Patel, Y. Social media’s role in the perception of radiologists and artificial intelligence. Clin. Imaging 2020, 68, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegmund, L.A. Social Media in Occupational Health Nursing: Helpful or Harmful? Workplace Health Saf. 2020, 68, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kross, E.; Verduyn, P.; Sheppes, G.; Costello, C.K.; Jonides, J.; Ybarra, O. Social Media and Well-Being: Pitfalls, Progress, and Next Steps. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2021, 25, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moraes, M.; Ruiz, M.; Puiggròs, C. ‘How long is its life?’: Qualitative analysis of the knowledge, perceptions and uses of fermented foods among young adults living in the city of Barcelona. Rev. Esp. Nutr. Hum. Diet. 2021, 25, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ouytsel, J.; Lu, Y.; Ponnet, K.; Walrave, M.; Temple, J.R. Longitudinal associations between sexting, cyberbullying, and bullying among adolescents: Cross-lagged panel analysis. J. Adolesc. 2019, 73, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.J.; Sáez, G.; Villanueva-Moya, L.; Expósito, F. Adolescent Sexting: The Role of Body Shame, Social Physique Anxiety, and Social Networking Site Addiction. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2021, 24, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, C.; Cooke, J.E.; Temple, J.R.; Ly, A.; Lu, Y.; Anderson, N.; Rash, C.; Madigan, S. The Prevalence of Sexting Behaviors Among Emerging Adults: A Meta-Analysis. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2020, 49, 1103–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gámez-Guadix, M.; De Santisteban, P.; Resset, S. Sexting among Spanish adolescents: Prevalence and personality profiles. Psicothema 2017, 29, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda, M.; del-Rey, R.; Walrave, M.; Vandebosch, H. Sexting in adolescents: Prevalence and behaviours. Comunicar 2020, 28, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villacampa, C. Teen sexting: Prevalence, characteristics and legal treatment. Int. J. Law Crime Justice 2017, 49, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, S.; Ly, A.; Rash, C.L.; Van Ouytsel, J.; Temple, J.R. Prevalence of Multiple Forms of Sexting Behavior Among Youth. JAMA Pediatr. 2018, 172, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Galindo, W.; Orosco-Fabian, J.R.; Salgado-Samaniego, E.; Pomasunco-Huaytalla, R. Sexting en estudiantes de educación secundaria. Horizontes. Rev. Investig. Cienc. Educ. 2022, 6, 970–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Gonzales, E.; Timoteo-Sánchez, A.E.; Diaz-Gonzales, K.B. Sexting en adolescentes y adultos de Lima metropolitana durante la pandemia COVID-19. Rev. Int. Salud Matern. Fetal 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Gualdo, A.; Sánchez-Romero, E.; Torregrosa, M. El lado oscuro de internet. ¿Predice el cyberbullying la participación en sexting? Rev. Latinoam. Psicol. 2022, 54, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, D.; Morelli, M.; Nappa, M.R.; Baiocco, R.; Chirumbolo, A. A Bad Romance: Sexting Motivations and Teen Dating Violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 6029–6049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, S.M.; Azzopardi, P.S.; Wickremarathne, D.; Patton, G.C. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla Esparza, C.; Nájera, P.; López-González, E.; Losilla, J. Development and Validation of the Adolescent Sexting Scale (A-SextS) with a Spanish Sample. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasburger, V.C.; Zimmerman, H.; Temple, J.R.; Madigan, S. Teenagers, Sexting, and the Law. Pediatrics 2019, 143, e20183183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias, V. La mujer y el sexting: El cuerpo y la mirada en las nuevas prácticas de exhibición sexual. Question 2018, 1, 061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzi, R. Sexting and Its Many Perils. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2019, 32, 453–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.M.; Drouin, M.; Coupe, A. Sexting Coercion as a Component of Intimate Partner Polyvictimization. J. Interpers. Violence 2019, 34, 2269–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassó, A.; Klettke, B.; Agustina, J.; Montiel, I. Sexting, Mental Health, and Victimization Among Adolescents: A Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciacca, B.; Mazzone, A.; Loftsson, M.; O’Higgins Norman, J.; Foody, M. Nonconsensual Dissemination of Sexual Images Among Adolescents: Associations With Depression and Self-Esteem. J. Interpers. Violence 2023, 38, 9438–9464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Macías, M.; Herrera, A.; Alonso-Ferres, M.; Herrera, M.C. Sexting is not always wanted: Consequences on satisfaction and the role of sexual coercion and online sexual victimization. An. Psicol. 2023, 39, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, A.C.; Gill, B.A.; Davenport, T.A.; Dowling, M.; Burns, J.M.; Hickie, I.B. Sexting, Web-Based Risks, and Safety in Two Representative National Samples of Young Australians: Prevalence, Perspectives, and Predictors. JMIR Ment. Health 2019, 6, e13338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chacón-López, H.; Romero, J.; Aragón, Y.; Caurcel, J. Construcción y validación de la escala de conductas sobre sexting. Rev. Esp. Orientac. Psicopedag. 2016, 27, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos, J.; Matas, A.; Chunga, G.; Rumiche, R. Validación de la escala de sexting (ECS) en una muestra de estudiantes universitarios de Perú. Rev. Meta Aval. 2021, 13, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, R.; Ramião, E.; Figueiredo, P.; Araújo, A. Abusive Sexting in Adolescence: Prevalence and Characteristics of Abusers and Victims. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 610474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chacón-López, H.; Caurcel-Cara, M.; Romero-Barriga, J. Sexting en universitarios: Relación con edad, sexo y autoestima. Suma Psicol. 2019, 26, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Mori, C.; Van, J.; Madigan, S.; Temple, J. Adolescent Sexting Involvement Over 4 Years and Associations with Sexual Activity. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 65, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Castro, Y.; Alonso-Ruido, P.; Lameiras-Fernández, M.; Faílde-Garrido, J.M. Del sexting al cibercontrol en las relaciones de pareja de adolescentes españoles: Análisis de sus argumentos. Rev. Latinoam. Psicol. 2018, 50, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ouytsel, J.; Walrave, M.; De Marez, L.; Vanhaelewyn, B.; Ponnet, K. A first investigation into gender minority adolescents’ sexting experiences. J. Adolesc. 2020, 84, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bragard, E.; Fisher, C. Associations between sexting motivations and consequences among adolescent girls. J. Adolesc. 2022, 94, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorós, E. Comportamiento Organizacional: En Busca del Desarrollo de Ventajas Competitivas (Vol. 58). USAT—Escuela de Economía. 2014. Available online: https://www.eumed.net/libros-gratis/2007a/231/index.htm (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Baumgartner, S.; Sumter, S.; Peter, J.; Valkenburg, P.; Livingstone, S. Does country context matter? Investigating the predictors of teen sexting across Europe. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 34, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currin, J. Linking Sexting Expectancies with Motivations to Sext. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2022, 12, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houck, C.; Barker, D.; Rizzo, C.; Hancock, E.; Norton, A.; Brown, L. Sexting and Sexual Behavior in At-Risk Adolescents. Pediatrics 2014, 133, e276–e282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, L.; Wu-Ouyang, B. Sexting Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Hong Kong and Taiwan: Roles of Sensation-Seeking, Gay Identity, and Muscularity Ideal. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2023, 52, 2373–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crimmins, D.; Seigfried-Spellar, K. Peer attachment, sexual experiences, and risky online behaviors as predictors of sexting behaviors among undergraduate students. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 32, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, J.R.; Le, V.D.; van den Berg, P.; Ling, Y.; Paul, J.A.; Temple, B.W. Brief report: Teen sexting and psychosocial health. J. Adolesc. 2013, 37, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner, B.F. Science and Human Behavior (No. 92904); Simon and Schuster: Cammeray, NSW, Australia, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Ato, M.; López-García, J.; Benavente, A. Un sistema de clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología. An. Psicol. 2013, 29, 1038–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MINSA. Norma Técnica de Salud Para la Atención Integral de Salud de Adolescentes. 1 November 2019. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/minsa/informes-publicaciones/1091057-norma-tecnica-de-salud-para-la-atencion-integral-de-salud-de-adolescentes (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Atkinson, R. Accessing Hidden and Hard-to-Reach Populations: Snowball Research Strategies. Sociol. Surrey 2001, 33, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Association, W.M. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B. Using Multivariate Statistics, 7th ed.; California State University: Northridge, LA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Costello, A.; Osborne, J. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2005, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, B. Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis: Understanding Concepts and Applications; American Psychological Association: Worcester, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Browne, M.W.; Sugawara, H.M. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, L.R.; Lewis, C. A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika 1973, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda, M.; Del Rey, R.; Dodaj, A.; Casas, J.; Sesar, K. Cross-Cultural Validation of the Sexting Behaviors and Motives Questionnaire (SBM-Q). Psicothema 2025, 37, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, M. Multivariable Analysis: A Practical Guide for Clinicians, 2nd Edition Edited by Katz, M.H. Study Design and Statistical Analysis: A Practical Guide for Clinicians Edited by Katz, M.H. Biometrics 2007, 63, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reise, S.P.; Moore, T.M.; Haviland, M.G. Bifactor Models and Rotations: Exploring the Extent to Which Multidimensional Data Yield Univocal Scale Scores. J. Personal. Assess. 2010, 92, 544–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Garcia, J.; Dawes, S.; Pardo, T. Digital government and public management research: Finding the crossroads. In Public Management Review; Taylor and Francis Ltd.: Abingdon, UK, 2018; Volume 20, pp. 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, F.F.; Peters, C.C.; Voorhis, W.R. Van. Statistical Procedures and their Mathematical Bases. Am. Math. Mon. 1941, 48, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M. A Further note on tests of significance in factor analysis. Br. J. Stat. Psychol. 1951, 4, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M. Tests of significance in factor analysis. Br. J. Stat. Psychol. 1950, 3, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. A second generation little jiffy. Psychometrika 1970, 35, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reise, S. The Rediscovery of Bifactor Measurement Models. Multivariate Behav Res 2012, 47, 667–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, J.; Anguiano-Carrasco, A. El análisis factorial como técnica de investigación en psicología. Papeles Psicól. 2010, 31, 18–33. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.F. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 2007, 14, 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, D.M. Testing for Factorial Invariance in the Context of Construct Validation. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2010, 43, 121–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klettke, B.; Hallford, D.J.; Clancy, E.; Mellor, D.J.; Toumbourou, J.W. Sexting and Psychological Distress: The Role of Unwanted and Coerced Sexts. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2019, 22, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, M.C.; Roche, K.; Stroebel, M.; Gonzalez-Pons, K.; Goharian, A. Sending, receiving, and nonconsensually sharing nude or near-nude images by youth. J. Adolesc. 2023, 95, 672–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K. Fit Difference Between Nonnested Models Given Categorical Data: Measures and Estimation. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2021, 28, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Yang, Y. RMSEA, CFI, and TLI in structural equation modeling with ordered categorical data: The story they tell depends on the estimation methods. Behav. Res. Methods 2019, 51, 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xiong, Q.; Zhang, X.; Xiong, Q. An Alternative Estimation for Functional Coefficient ARCH-M Model. Theor. Econ. Lett. 2016, 6, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, Y.; Martínez, W.; Calderón, C.; Solís, F. Factores psicológicos asociados a la práctica del sexting en jóvenes del Departamento de Estelí. Rev. Cient. FAREM-Estelí 2020, 32, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodaj, A.; Sesar, K.; Jerinić, S. A Prospective Study of High-School Adolescent Sexting Behavior and Psychological Distress. J. Psychol. 2020, 154, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-Pineda, A. Tesis Doctoral Sobre Sexting en Adolescentes y Adultos. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Almería, La Cañada de San Urbano, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paintsil, J.A.; Adde, K.S.; Ameyaw, E.K.; Dickson, K.S.; Yaya, S. Gender differences in the acceptance of wife-beating: Evidence from 30 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Women’s Health 2023, 23, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo-Arias, A.; Oviedo, H. Propiedades Psicométricas de una Escala: La Consistencia Interna. Rev. Salud Pública 2008, 10, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Castro, Y.; Alonso-Ruido, P.; González-Fernández, A.; Lameiras-Fernández, M.; Carrera-Fernández, M.V. Spanish adolescents’ attitudes towards sexting: Validation of a scale. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 73, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, D.; Baiocco, R.; Morelli, M.; Chirumbolo, A. Psychometric properties of the Sexting Motivations Questionnaire for adolescents and young adults. Rass. Psicol. 2016, 33, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, M.W. Exploratory Factor Analysis: A Guide to Best Practice. J. Black Psychol. 2018, 44, 219–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo-Cárdenas, S.; Caycho-Rodríguez, T.; Barboza-Palomino, M.; Reyes-Bossio, M. Insatisfacción corporal en mujeres universitarias: Nuevas evidencias psicométricas del Body Shape Questionnaire de 14 ítems (BSQ-14). Cuad. Psicol. Deporte 2021, 21, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. Items. | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | CHI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.29 | 1.06 | 0.16 | −1.22 | 0.68 |

| 2 | 2.03 | 1.00 | 0.51 | −0.95 | 0.55 |

| 3 | 2.02 | 0.95 | 0.48 | −0.83 | 0.64 |

| 4 | 2.40 | 0.99 | 0.00 | −0.83 | 0.64 |

| 5 | 2.21 | 1.07 | 0.34 | −1.15 | 0.70 |

| 6 | 2.33 | 1.10 | 0.14 | −1.16 | 0.70 |

| 7 | 2.18 | 0.98 | 0.31 | −0.98 | 0.60 |

| 8 | 2.09 | 1.01 | 0.40 | −1.06 | 0.52 |

| 9 | 1.97 | 0.97 | 0.52 | −0.92 | 0.57 |

| 10 | 2.13 | 1.01 | 0.32 | −1.10 | 0.67 |

| 11 | 2.18 | 1.02 | 0.33 | −1.06 | 0.67 |

| 12 | 2.08 | 0.95 | 0.33 | −0.99 | 0.69 |

| 13 | 2.15 | 1.02 | 0.28 | −1.17 | 0.70 |

| 14 | 2.28 | 1.04 | 0.15 | −1.22 | 0.68 |

| 15 | 2.29 | 1.05 | 0.09 | −1.28 | 0.66 |

| 16 | 3.00 | 1.11 | 0.02 | −1.35 | 0.73 |

| Internal Motivators | External Motivators | H2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 0.77 | 0.86 | |

| P2 | 0.79 | 0.83 | |

| P3 | 0.77 | 0.82 | |

| P4 | 0.69 | 0.78 | |

| P5 | 0.69 | 0.82 | |

| P6 | 0.69 | 0.84 | |

| P7 | 0.76 | 0.82 | |

| P8 | 0.75 | 0.86 | |

| P9 | 0.67 | 0.80 | |

| P10 | 0.71 | 0.83 | |

| P11 | 0.66 | 0.83 | |

| P12 | 0.70 | 0.85 | |

| P15 | 0.54 | 0.67 | |

| P17 | 0.75 | 0.79 | |

| P18 | 0.87 | 0.86 | |

| P19 | 0.73 | 0.85 |

| (p)X2 | Df | x2/df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (16 items) | 0.000 | 120 | 33,323.862 | 0.962 | 0.962 | 0.106 | 0.054 |

| Model 2 (8 items) | 0.000 | 28 | 11,699.186 | 0.991 | 0.988 | 0.068 | 0.027 |

| Modelo | χ2 | Δχ2 | gl | Δgl | P | CFI | ΔCFI | RMSEA | ΔRMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configural | 19.05633 | 40 | 0.001 | 0.973 | 0.022 | ||||

| Metric | 21.59985 | −2.54352 | 47 | −7 | 0.001 | 0.987 | −0.014 | 0.018 | 0.004 |

| Scalar | 24.8401 | −3.24025 | 54 | −7 | 0.001 | 0.988 | −0.001 | 0.017 | 0.001 |

| Strict | 29.16796 | −4.32786 | 62 | −8 | 0.001 | 0.989 | −0.001 | 0.016 | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Palomino-Ccasa, J.; Tuanama Shupingahua, A.; Torrejon Chuqui, L.P.; Saldaña Sánchez, J.K.; Tantaruna Diaz, M.Y.; Malca-Peralta, S.S.; Millones-Liza, D.Y. Sexting Motivation Scale (EMS) in Peruvian Youth. Sexes 2025, 6, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6020020

Palomino-Ccasa J, Tuanama Shupingahua A, Torrejon Chuqui LP, Saldaña Sánchez JK, Tantaruna Diaz MY, Malca-Peralta SS, Millones-Liza DY. Sexting Motivation Scale (EMS) in Peruvian Youth. Sexes. 2025; 6(2):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6020020

Chicago/Turabian StylePalomino-Ccasa, Joel, Analí Tuanama Shupingahua, Lady Pamela Torrejon Chuqui, Jhon Kenedy Saldaña Sánchez, María Yndrid Tantaruna Diaz, Segundo Salatiel Malca-Peralta, and Dany Yudet Millones-Liza. 2025. "Sexting Motivation Scale (EMS) in Peruvian Youth" Sexes 6, no. 2: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6020020

APA StylePalomino-Ccasa, J., Tuanama Shupingahua, A., Torrejon Chuqui, L. P., Saldaña Sánchez, J. K., Tantaruna Diaz, M. Y., Malca-Peralta, S. S., & Millones-Liza, D. Y. (2025). Sexting Motivation Scale (EMS) in Peruvian Youth. Sexes, 6(2), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6020020