1. Introduction

Positive emotions improve our health and well-being through broadening our mindsets, promoting creativity and bonding, allowing us to build our long-term intellectual, social, and psychological resources [

1]. These beneficial effects have increased interest in designing for positive emotions [

2]. More recently, designers are investigating how to elicit discrete and distinct positive emotions, such as pride [

3], fascination [

4], and surprise [

5], because of their unique beneficial functions. Specifically, the emotion of awe is being increasingly explored for its transformative potential and is considered highly relevant to design regarding its effect on users’ behaviors [

6]. Awe is considered transformative because it can reshape an individual’s worldviews, and change one’s perspective and identity [

7]. Awe’s transformative power lies in its ability to take our breath away and make us feel mind-blown as we try to accommodate these new stimuli into our schema, a mental structure that helps us understand the world. Awe is an emotion that can be characterized by feelings of wonder and surprise, and is often felt in experiences involving nature, religion, spirituality, art, music, and architecture [

8]. Awe has unique beneficial functions such as making people more prosocial, diminishing their sense of self, which results in certain behavior tendencies such as inclinations to share, collaborate, and engage in collective action [

9]. Another beneficial function is that people feel more connected to others and view themselves as part of a larger entity such as “member of the universe” or “inhabitant of the earth” [

10]. Awe even reduces aggressive behaviors [

11] and promotes green consumption [

12]. More importantly, evoking awe has the potential to contribute to the well-being of oneself as well as to a collective [

8]. Awe has shown to increase experiential creation, making people open to learning; and increasing their tendency to favor experiential products over premade ones [

13].

To date, in design research, most studies on awe have been conducted in lab conditions, by using technologies such as Virtual Reality (VR) e.g., [

14,

15]. Virtual environments are believed to have a high potential to evoke awe and is a commonly chosen tool because of its efficiency to generate presence, immersion, and create an “other-than-self” experience for epistemic expansion [

6]. However, this conventional approach would give little guidance for designers who want to create things that facilitate the experience of awe in the real world beyond highly controlled lab conditions. While VR can serve as an effective medium through which an awe experience can manifest, simulating suggestive awe-eliciting conditions would not inform how awe can be deliberately designed for. In addition, most attempts to elicit awe use nature imagery, whether its 2D images or videos, or 3D in a VR environment e.g., [

9,

14]. By only using nature imagery, the awe elicitation method focuses on only one aspect of the definition of “vastness,” the literal size and physicality, even though vastness can be anything that is “much larger than self, or the self’s ordinary level of experience” [

8]. There is a wide range of awe elicitors beyond nature, including interpersonal elicitors, collective activities such as rallies and sports games, spiritual experiences, and cultural artifacts [

16], but they have been largely unexplored in design. Although some awe-evoking art objects that go beyond nature imagery exist (for an overview of such examples, see [

17]), they rarely explicate how they were created and provide few references to the underlying decisions in the process. Thus, while they offer designers inspiration to design for awe, they do not offer an explicit approach to achieve the intended emotional impact (i.e., elicitation of awe). This implies creating an awe experience in human–product interactions can still be challenging for those who want to evoke awe and utilize its experiential effects through their designs.

This paper aims to explore design strategies to design for awe, so that it can serve as a reference for designers to develop an understanding of the experience of awe in human–product interactions and how awe can be purposefully evoked through design. Here, we define design strategies as pathways that designers can take to reach a design goal (both tangible and intangible), supporting them to systematically identify and consider certain factors related to the goal fulfillment, and how the factors can be effectively manipulated in the design process (e.g., design for interest by making the interactions novel and complex). This study generates a set of design strategies through a bottom-up and top-down approach. First, the top-down approach investigates the mechanism of awe through the perspective of appraisal theory. Meanwhile, the bottom-up approach explores the patterns of when and how people experience awe in relation to products through a survey in which participants report their personal experiences of awe and design examples. Through an analysis of a variety of designed artifacts that people consider evoking awe, we intend to learn what designs make people feel awe and what aspects of the designs are associated with elicitation of awe, and generate insights on ways in which products can be designed to evoke awe (i.e., design strategies). We first discuss the emotion of awe and its underlying causes based on appraisal theory to develop a theoretical foundation. Then we dive into the study methods and process through which six design strategies are formulated. Next, we describe each design strategy in detail with design examples and suggestions for implementation. The paper ends with a discussion on how the resulting strategies can be applied in design practice and the relevance of focusing on the long-term experiential value of awe, along with future research directions.

2. Cause of Awe

There are many different theories explaining the experience of emotions in product design, such as Norman’s neurobiological approach [

18], Hassenzahl’s approach based on universal psychological needs [

19], or Desmet’s appraisal approach [

20]. Appraisal theory says that emotions are elicited from a distinct set of appraisals or assessment patterns [

21]. Appraisals serve to evaluate one’s needs and environmental conditions based on several factors such as control, pleasantness, and certainty, based on which they would classify the situation as beneficial, detrimental, or irrelevant to their well-being, leading to positive or negative emotions [

22]. These different emotions enable one to adapt to different environmental demands or opportunities [

23]. What is noteworthy is that depending on the person, the same situation can result in different emotions because the ways people appraise the situation can be different, affected by their own values and concerns [

24]. This implies that in human–product interactions, the types of emotion are not determined by the product itself, but by the personal concerns and contexts where the product is placed and how it is used, what meanings the user attributes to it, and how the user talks about it [

25,

26]. For example, a smart watch that controls multiple devices may inspire a person with its sophisticated features today, but the same person may be worried by it tomorrow when realizing that its potential to leak their private information. Hence, it is crucial to consider that the emotion can be evoked not only by the designed technology or its appearance but also by the relational meaning of the designed experience, such as personal associations, concerns, social implications of the design, which can serve as points of reference for design conceptualization and evaluation [

26,

27].

Appraisals of Awe

Recent research has investigated distinguishing emotions from one another, and in particular, differentiating between positive emotions. Although positive emotions are less differentiated than negative emotions in terms of expressions and action tendencies [

22], recent studies have shown that positive emotions could be differentiated by their appraisal patterns [

28,

29]. In Keltner and Haidt’s seminal work [

8], they found that awe is evoked by appraisal of (1) perceived vastness and (2) a need for accommodation. Perceived vastness refers to anything that is experienced as larger than the self’s ordinary or normal range of experiences. Vastness can be both perceptual, in which something is physically bigger in scale, such as a grove of tall eucalyptus trees. Vastness can also be conceptual, in which an idea may embody immense implications, such as being in the presence of an idol. The second appraisal component is a need for accommodation, in which accommodation refers to the process of modifying our schemas to make sense of the expanded frame of the perceived vastness. Both appraisal dimensions are needed to experience awe because if either component is missing, then the experience is more likely to be closely aligned with a different emotion. For example, accommodation without vastness could be surprise, and vastness without accommodation could be worship or reverence [

8].

Awe appraisals patterns have been further evaluated with various behavioral manifestations: awe appraisal patterns involve self-diminishment and high stimulus-focused attention, while decreased self-focused attention [

10]. Tong [

28] evaluated the appraisal patterns of 13 different positive emotions, in which its findings aligned closely with the findings of Shiota, Keltner [

10]. Awe scored low on the “Achievement” factor, reflecting that a goal has been achieved through personal means and control, and likewise high on the “External Influence” factor, reflecting that the events are subject to non-controllable forces. Awe also scored low on the difficulty factor, reflecting the appraisal of a non-problematic and pleasant experience. Further, most recently, the Awe Experience Scale (AWE-S) has been developed to evaluate awe experiences, using six facets of the awe experience, namely vastness, need for accommodation, altered time perception, self-diminishment, physical sensations, and connectedness [

30].

Appraisal theory is particularly useful for the purpose of the current study because it elucidates the underlying principles of awe and proves that the appraisal perspective offers a way of construing the causes of distinct emotions [

31]. It was, therefore, decided to use the appraisal patterns of awe (i.e., perceived vastness and a need for accommodation) as a theoretical framework of the current study (top-down). However, the appraisal patterns are not directly applicable to design, because the framework itself does not show how the appraisals can be translated to the design of dynamic interactions with products. While useful in understanding the general conditions that cause awe, this might be too abstract for designers and limited in offering actionable insights in their attempts to systematically evoke awe. Therefore, using awe experiences inductively derived from real-world examples stimulated by design and technology (bottom-up), the paper explored how to use the general appraisal patterns (top-down) as the basis for designing for awe.

4. Results

The affinity groups were then translated into concrete design strategies. The patterns that described the effects of awe rather than eliciting conditions of awe were screened. For example, one pattern was that many people contemplate humanity, humanity’s progress, and innovation, and what it means to be human. However, this pattern did not necessarily tell us anything about how the design was made but some of the behavioral effects of awe. Additionally, other patterns could be broken down further and be created by a mix of different design strategies. For example, one pattern that emerged from the design examples was the sense of otherworldliness created by the user’s immersion in the design. However, further analysis revealed that immersion was the combination of overwhelmingly high complexity and perception of hierarchy, rather than a standalone strategy. Lastly, each design strategy needed to relate back to the main two appraisals of awe: vastness and need for accommodation. The design strategy, novelty with overwhelmingly high complexity, for example, could be related to these appraisals: the overwhelming complexity of the design could create a sense of vastness as the user observed what seemed to be an infinite amount of detail, and the novelty of the design stimulated the need for accommodation, as the user tried to adjust their schema to a new perspective.

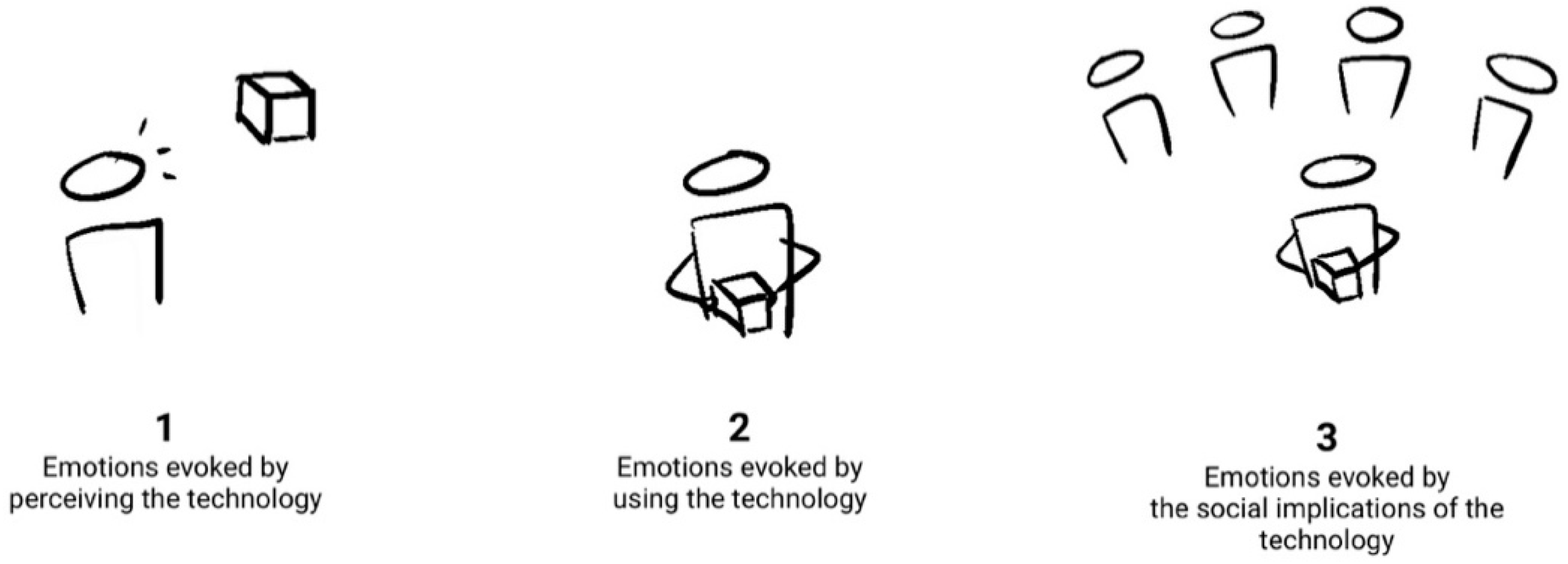

Once the strategies were identified, they were categorized based on the three sources of product emotions proposed by Desmet and Roeser [

27] to identify the ways in which awe was evoked in the interactions with the artifacts (see

Figure 1). The first source of emotion comes from perceiving the design with the senses, such as seeing, touching, and hearing it (e.g., “I love my action camera because of its clutter-free shape and hard texture.”). The second source of emotion comes from using, operating, and managing the design, such as the enjoyment of using its functions or interactive qualities (e.g., “I am relieved because of my action camera’s automatic backup function, which enables me to keep and access the memories of my family trip.”). The third source of emotion comes from the social implications of the design, such as emphasizing one’s identity or relationship with others (e.g., “the pictures I posted on social media well illustrate my energetic and explorative character and gained me some fame in the photo community).

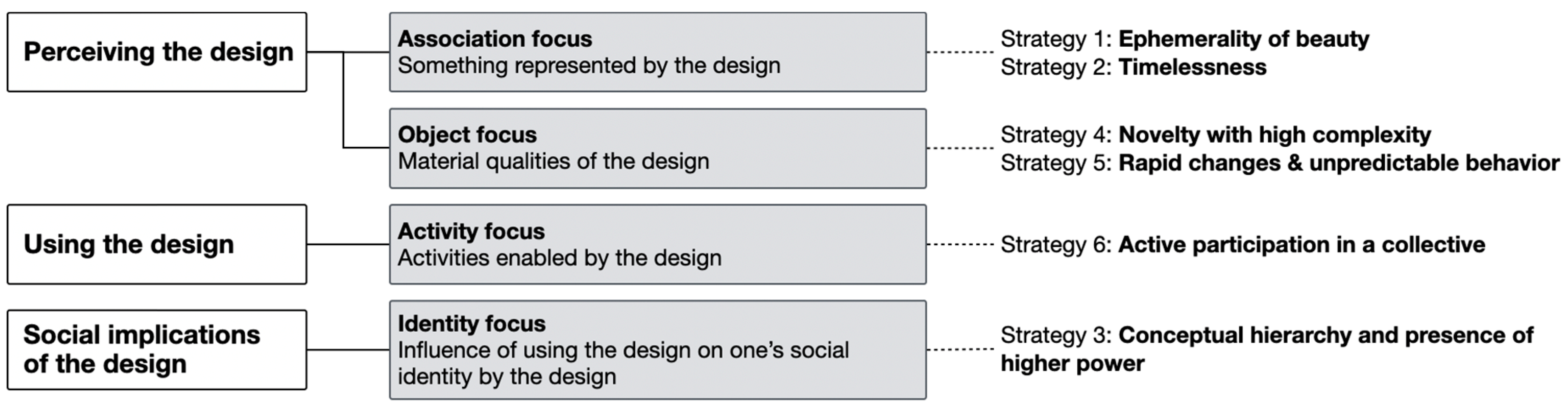

Based on these three overarching categories of perceiving the design, using the design, and social implications of the design, six design strategies were further categorized. The strategies were clustered and categorized based on their similarity in terms of their causes guided by the framework. For example, design Strategy 4 and 5 on novelty, complexity, and unpredictable behavior were categorized underneath perceiving the design with perception-focus. Based on the narratives and the context in which these strategies were used, the stimulation from perceiving the design itself was considered what evoked awe. In this case, the design did not need to be used, nor did it inspire any associations with social implications.

Figure 2 shows how the strategies were classified based on the three sources of product emotions.

5. Six Strategies to Design for Awe

This section describes the resulting six strategies to design for awe. Each of the six strategies is detailed with the following structure: how the strategy supports elicitation of awe, how the source of emotion is related to the awe appraisal pattern, associated design examples provided by the participants, and how to apply the strategy to design a product in a concrete and specific way, i.e., implementation. The suggestions for strategy implementation were derived from the descriptions of participants’ awe experiences in relation to the chosen artifacts and their aspects. Note that the implementation suggestions are based on the ways that we observed the strategies being applied in the collected data. There can be a wide range of alternative ways each of the strategies can be utilized to manipulate the design.

Figure 3 proves a comparative overview of the six strategies.

5.1. Design Strategy 1—Ephemerality of Beauty

One strategy to evoke awe is by creating a design that embodies ephemerality of beauty. The source of awe comes from perceiving the design and its association with the passage of time. Passage of the time is in line with awe’s appraisal pattern: perceived vastness and need for accommodation. The temporal scarcity of the design may lead people to realize that their resources (e.g., time on earth) are temporary and that they may have witnessed a moment that they may not ever experience again. This “once in a lifetime” mentality can create perceived vastness, as they realize that this experience is one small moment within the many years of their lifetime. The unpredicted change in perspective from one’s day-to-day view, to a lifetime view, stimulates a need for accommodation.

5.1.1. Examples

Some examples that use this strategy to create a transient aesthetic experience include fireworks and water features such as fountains (

Figure 4a). Other examples of nature experiences are blossoming flowers, the changing color of leaves during fall, or sunset and sunrise. One participant described walking through a path during the fall and seeing the changing colors: “

It was a combination of all the colors I liked, so I had to stop walking and take a moment to just take it in and appreciate how beautiful it was. At that moment, I felt thankful that I was able to see something like that by chance […]” (

Figure 4b). Use of transient materiality is also often used by artists: two participants described a light sculpture installation by TeamLab in which the light beams change orientation to create a unique shape and pattern every time:

“[…] light and music pirouette before my eyes. Entranced, I lose a sense of time and space, embraced by an entity which swathes me in light and sound” (

Figure 4c). Similarly, Olafur Elaisson used melting ice in his art piece, Ice Watch, to evoke awe by displaying the transience of nature’s beauty (

Figure 4d).

5.1.2. Implementation

To apply the design strategy in a concrete way, designers can create products, spaces, or installations that satisfy two components: beauty and changing appearance of the design. While beauty is a subjective quality, the general goal should be to create a design that people may appreciate and desire to experience again [

36,

37]. In the collected examples, beauty was addressed by, in general, incorporating organic complexity, such as patterns in nature, using colors. For example, in the participant’s description of leaves changing color specifically points out that it was the “

combination of all the colors” that made her pause and reflect, which reveals one way this design strategy can be implemented (

Figure 4b). The participant’s description of TeamLab’s light sculpture reveals another implementation possibility, when he described the movement of light and sound as “

pirouette” and “

swathes.” These verbs imply organic motion, which is another way this strategy of ephemeral beauty can be implemented. The changing appearance component of the design can be achieved through many means such as using shifting patterns, making the design disappear or disintegrate, or using transient and non-solid materiality such as water, fog, wind, or light, as evidenced in the collected data. Three of the above four examples use manipulation of non-solid materials to create a transient and ephemeral effect. If the design is beautiful but not changing in appearance, it will likely evoke other positive emotions such as inspiration or pride, but not awe. Only when beauty and transience are combined, can we get the effect, in which the person does not try to analyze but rather stands back and appreciates the design, creating that moment for reflection on the passage of time.

5.2. Design Strategy 2—Timelessness

Another strategy that evokes awe is to create a timeless design. Timeless designs connote a sense of endurance and are often considered as classics or icons. Similar to the previous strategy, the source of awe comes from perceiving the design and its association with the passage of time. However, this time the method, through which the association is formed, is different. The enduring qualities of the design remind people that the design has persisted beyond one’s own lifespan. This mentality can stimulate perceived vastness, as they realize that they are only one of the many thousands of people who have used or experienced the design. The unpredicted change in perspective from one’s lifetime to the design’s timeline of existence, stimulates a need for accommodation. In line with awe’s behavioral impact, fulfillment of the appraisals makes us feel small and insignificant in comparison.

5.2.1. Examples

One design example of this strategy is Marc Newson’s Ford 021c (

Figure 5a), which uses a neo-retro style to achieve timeliness: “

Marc Newson’s […] Ford 021c remains my favorite car ever. […] This is so clearly from the future and the past at the same time. It does not care about the status quo. It entices me to take it for a spin like no other car does.” Another example is the Capitol building in Washington D.C. (

Figure 5b) which has become a timeless landmark through its decades-long existence. “

What was truly awe-inspiring at this moment was realizing that I was walking the same steps as the founders of this country had while they were doing the work that I had only read about in history textbooks.” Participants listed examples of personal experiences and products, or technology that represented human race’s achievements and expressed thoughts about how far we have come and where we will go in their personal lives or in regarding humanity as a whole.

5.2.2. Implementation

Creating a timeless design may seem very abstract to a designer. Some designs become timeless naturally with age, as with most landmarks and architectural designs like the Capitol building or Grand Central station (

Figure 5c,d). However, as observed in the collected design examples, there are ways to apply this strategy in a concrete way, such as creating designs that are deprived of trendy aesthetics. The Nike Air Force 1 is an example of this implementation suggestion (

Figure 5b). The participant described the design as “

iconic and simple,” “

bland and minimalistic, yet these qualities are exactly what makes the shoes awe-inspiring.” The participant attributed its timeless and iconic qualities to the lack of ornamentation. As suggested by Lobos [

38], to achieve timelessness, designers could strive for simplicity by refraining from aesthetic cues that may indicate time markers such as particular trends. Another way to achieve timelessness can be by using a neo-retro design style [

39]. Marc Newson’s Ford 021c was described by the participant as “

clearly from the future and past at the same time” (

Figure 5a). Neo-retro products have design characteristics from the past but are also technologically advanced with new functionalities [

40].

5.3. Design Strategy 3—Conceptual Hierarchy and Presence of Higher Power

The strategy, conceptual hierarchy, and presence of higher power, mean to perceive a power dynamic in which we are lower in status relative to the designed object. The source of awe comes from the social implications of the design, which allows us to define our identity relative to the higher power. The appraisal component “perceived vastness” is achieved when the user realizes that the design is vastly more powerful through its ability to significantly exceed the human capacity in some way, as well as the enormous number of people that the design can affect. The result is a shift in how we understand our identity: from a more egotistical perspective, in which we are the center of the world, to a mindset in which we are merely a subject of something greater, stimulates another appraisal component “a need for accommodation.”

5.3.1. Examples

Participants’ responses included the Tesla Cybertruck (

Figure 6a): “

The car also has a presence when you stand next to it, it almost feels like a living beast, ready to roar to life.” Designs that evoke a sense of power and hierarchy included being in the presence of an idol or leader, and looking up at a massive monument were also some of the most common awe examples. One participant attended a concert for one of his favorite artists and felt in awe of the artist (

Figure 6b): “

An inspiration for my music and life, in the flesh. There was a tightness in my throat and I fought back tears. I couldn’t stop saying ‘wow’.” One participant’s response, describing listening to a rock band (

Figure 6c), exemplifies using immersion to evoke awe: “

I remember sitting next to my record player and just listening through the entire album with my eyes closed. I felt so physically small amidst the sound.” The art piece, Drifter, by Studio Drift of what appears to be a huge cement block floating in the ceiling (

Figure 6d), also conjures awe because its size and placement in the air make it look more powerful.

5.3.2. Implementation

The strategy can be manifested in design through a variety of means as long as the design appears and feels more powerful than its context with the user. One simple way is to create a stark contrast between the design and its surroundings, making the design appear more powerful and giving it more presence. It is common to place the design on a pedestal or stage, against a backdrop of the opposite color, or high up from the ground to make it stand out more and reinforce the hierarchy. Some designs also rely on their sheer size or appearing massive relative to its surroundings to make the design feel more powerful. Drifter, for example, uses this strategy by contrasting the block to humans to create a sense of scale and hierarchy (

Figure 6d). The participant wrote, “

how could it be that such a massive concrete block could hang like that? It made me realize that I am so small and powerless in comparison.” Another manifestation is to use immersion and surround the user with the design, thereby making them feel small relative to their surroundings. This approach was commonly observed in the collected examples of physical installations and spatial configurations. Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirrors was a commonly cited design that inspired awe. One participant wrote, “

you are surrounded by an infinite expanse of light, with a pool of water underneath your feet. You are closed into the space, and truly feel transported to another dimension.”

5.4. Design Strategy 4—Novelty with Overwhelmingly High Complexity

One strategy to evoke awe is by creating a novel design that is highly complex. The source of awe comes directly from perceiving the design and its complex qualities, which may include detailed intricacy, repeated patterns, or an abstract concept that is difficult to grasp. When viewing an overwhelmingly complex design with those qualities, the person is likely to feel a perceived vastness because it is impossible to quantify what may seem like an infinite amount of repetition or ineffable complexity. The design’s novel aspects could lead people adjust their perspective to make a sense of what they are experiencing or cope with the complexity, which can stimulate a need for accommodation.

5.4.1. Examples

One example of a design that employs this strategy is Ai Wei Wei’s artwork of 100 million handmade porcelain sunflower seeds (

Figure 7a). The design is simultaneously novel and complex since it may look like sand or stone from afar, but once you approach closely to it, you realize that the floor is laden with intricate seeds. The complexity comes from the incomprehensible number of seeds and their individual delicacy. Similarly, two participants described Agnes Denes’ works, such as the Fibonacci sequence pyramid (

Figure 7b): “

She hand wrote the sequence, and the pyramid of numbers spanned a 10-foot long table. This felt awe-inspiring because I can tell it took forever to make/feels very labor-intensive, and I was trying to imagine the number of hours that she had to pour into making something so meticulous.” The process of understanding abstract theories can also be awe-inspiring because of their vast applicability. One participant described learning about quotient topologies and its relation to the Mobius strip (

Figure 7c): “

…Not only could I connect the math to the physical, but I made a broader connection too, that this was the reason I did the math.” Another participant described M.C. Escher’s staircase drawing (

Figure 7d), which also captures both novelty and complexity at the same time: “

M.C. Escher’s drawings seem impossible and conceivable at the same time, especially his staircase illusions. The sense of awe comes from commonplace objects being manipulated in an unexpected way. I feel awe because I can’t understand what’s going on, but it seems familiar and correct at the same time.”

5.4.2. Implementation

Novelty may be subjective since what is novel to one person, may not be for another. However, novelty can be more concretely implemented by considering a mismatch between expectations and reality [

5,

41]. As described by the participant who wrote about M.C. Escher’s staircase, she ascribed the sense of awe to “

commonplace objects being manipulated in an unexpected way.” Something that looks new can have familiar qualities (i.e., visual novelty), and something that looks familiar may have new qualities (i.e., hidden novelty). For example, a mason jar made from lightweight plastic will create hidden novelty since it looks familiar but has unfamiliar materiality. Complexity can be achieved by incorporating intricate repeating patterns, as seen in the collected data. For example, one participant described egg carving: “

seeing such beautiful intricate patterns on the eggshell knowing how fragile it is to work with inspires a sense of awe: both at the work itself and at the time, effort, and skill of the artist.” Optical illusions, such as M.C. Escher’s staircase, can also create complexity, as well as novelty, since the effect of the design changes depending on the person’s location and perspective. The use of large numbers can also conceptually convey a sense of complex, infinite, and unquantifiable vastness since numbers or theories are an abstract representation that can feel difficult to grasp. For example, the sheer magnitude of Ai Wei Wei’s 100 million porcelain seeds and Agnes Denes’ 10 foot-long pyramid of numbers, makes the design almost inconceivable, as described by the participant: “

I was trying to imagine the number of hours […] into making something so meticulous.” Ultimately, the design should not be easily quantifiable or analyzable based on its appearance to ensure its high complex character.

5.5. Design Strategy 5—Rapid Changes and Unpredictable Behavior

The strategy “rapid changes and unpredictable behavior” means that the designed object or experience should not be fully controllable by the user, and its quality (e.g., appearance) keeps changing. The source of awe mainly comes from perceiving the design and engaging its design qualities with one’s senses. By experiencing the unpredictable nature of the design and how it rapidly floods and overwhelms the senses, its vastness is perceived. Similar to the previous strategy, the inability to quantify or immediately analyze the design creates a sense of vastness as we become overwhelmed with the changes. The unpredictable behavior also makes one realize that she/he cannot control the situation and that many things in life are subject to a higher power. The lack of control over the design shifts us from our day-to-day perspective, combined with overwhelming new information, inciting a need for accommodation. This strategy could also be used in combination with the strategies “ephemerality of beauty,” “conceptual hierarchy and presence of higher power,” and “novelty with overwhelming complexity.” The design’s unpredictable nature is likely to enhance the other strategies in fulfilling the two appraisal components of awe: perceived vastness and need for accommodation.

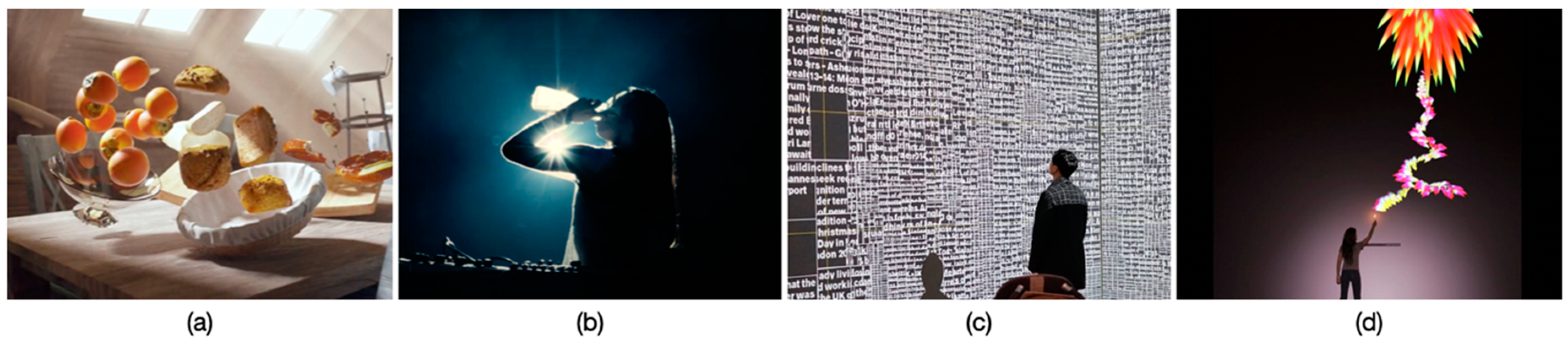

5.5.1. Examples

Participants’ examples included digital experiences such as videos and animations in which random and abrupt changes disorient the viewer. One participant added an example of a video in which objects start to randomly fly in many directions out of the blue (

Figure 8a): “

It was completely unexpected and mind-blowing since there’s no indication that something crazy like that will happen. And when he opens the door, we’re once again surprised that he’s floating in space. The sudden and unexplained changes left me in awe as I tried to process what was happening as quickly as possible.” In another example, the participant described going to a DJ set (

Figure 8b): “

Seiho spins a mix of frenetic beats while ripping insane keyboard solos. The music’s energy, his vigor, and flashing lights made this video especially awe-inspiring.”

5.5.2. Implementation

Both components of rapid changes and unpredictable behavior appeared critical to evoke awe. If the design is just unpredictable but not instantaneous enough, the user would be confused or frustrated. If the design changes its appearance rapidly but predictable, the user may feel bored. Rapid changes can be expressed in design by flashing lights, screens, or animations. A physical product, such as a kaleidoscope, could also quickly change in patterns and colors. These implementation options are exemplified in Seiho’s DJ set and the video of flying objects in which the changes in lighting, music, and imagery were characterized as “frenetic” and “sudden.” The unpredictable behavior component means that the product or experience should minimize having user controls or interfaces to directly manipulate the design. As observed in the data points for this design strategy, most designs were videos, installations, or events, in which user controls were limited.

5.6. Design Strategy 6—Active Participation in a Collective

The last design strategy describes evoking awe through a participatory activity in which many people can partake simultaneously to work towards a common goal or interest. The source of awe comes from the consequences of directly using the design and what the design enables us to do. The design’s direct interaction with multiple people or the representation of many people creates a sense of vastness because they are surrounded by a sea of people or their visual representation. The user realizes that she/he is not alone, but rather part of a much larger community or group, and this shift in perspective induces a need for accommodation. As a result, they experience awe and its effects, such as feeling connected with others.

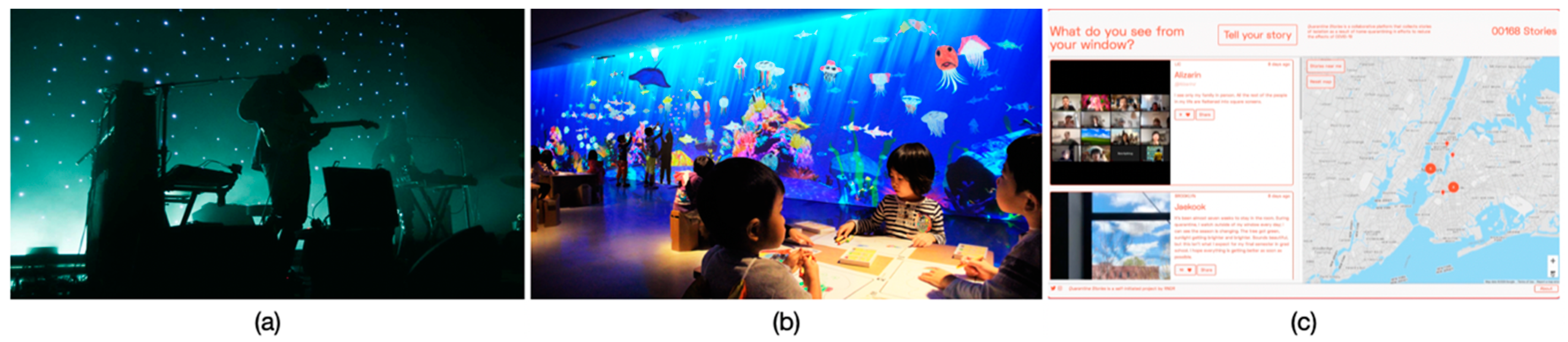

5.6.1. Examples

Many participants cited examples of going to a concert or working in a team as awe-inspiring moments, in which they are surrounded by people. One participant described going to see her favorite band (

Figure 9a): “

This combination of effects made me feel a sense of mystery and strangeness. I felt very connected to everyone around me who shared my love of Beach House. I felt very close to being overwhelmed with my emotion.” Some experiences can also be an abstract representation of contributing to a larger group, such as the TeamLab aquarium, where you can draw a fish to contribute to the pool (

Figure 9b). By looking at the pool of swimming fish made by so many different kids surrounding your own fish, a visualization of the community that facilitates a new perspective is created.

5.6.2. Implementation

This strategy can be directly manifested in design that invites and allows multiple to participate in its usage simultaneously by incorporating multiple affordances that indicate collective use. The experience can be further facilitated by incorporating some aspects that invite its participants to take collective action toward a common goal. For example, one participant described the artwork of I WAS HERE by Laura Schnitger: “the sequin tapestry is made unique by the everyday people walking by and leaving their marks […]. The exhibit itself is special because people come and go, leaving behind traces of themselves for other people to see and interact with.” If the design cannot directly engage multiple people, then a visual representation of other people’s presence and their contribution can be helpful in encouraging others to contribute to the collective. TeamLab’s aquarium, for instance, allows the user to upload their drawings into the digital ocean, and displays the scanned drawings of every individual, conveying each user’s contribution to the collective presence.