Do Communities Really “Direct” in Community-Directed Interventions? A Qualitative Assessment of Beneficiaries’ Perceptions at 20 Years of Community Directed Treatment with Ivermectin in Cameroon

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

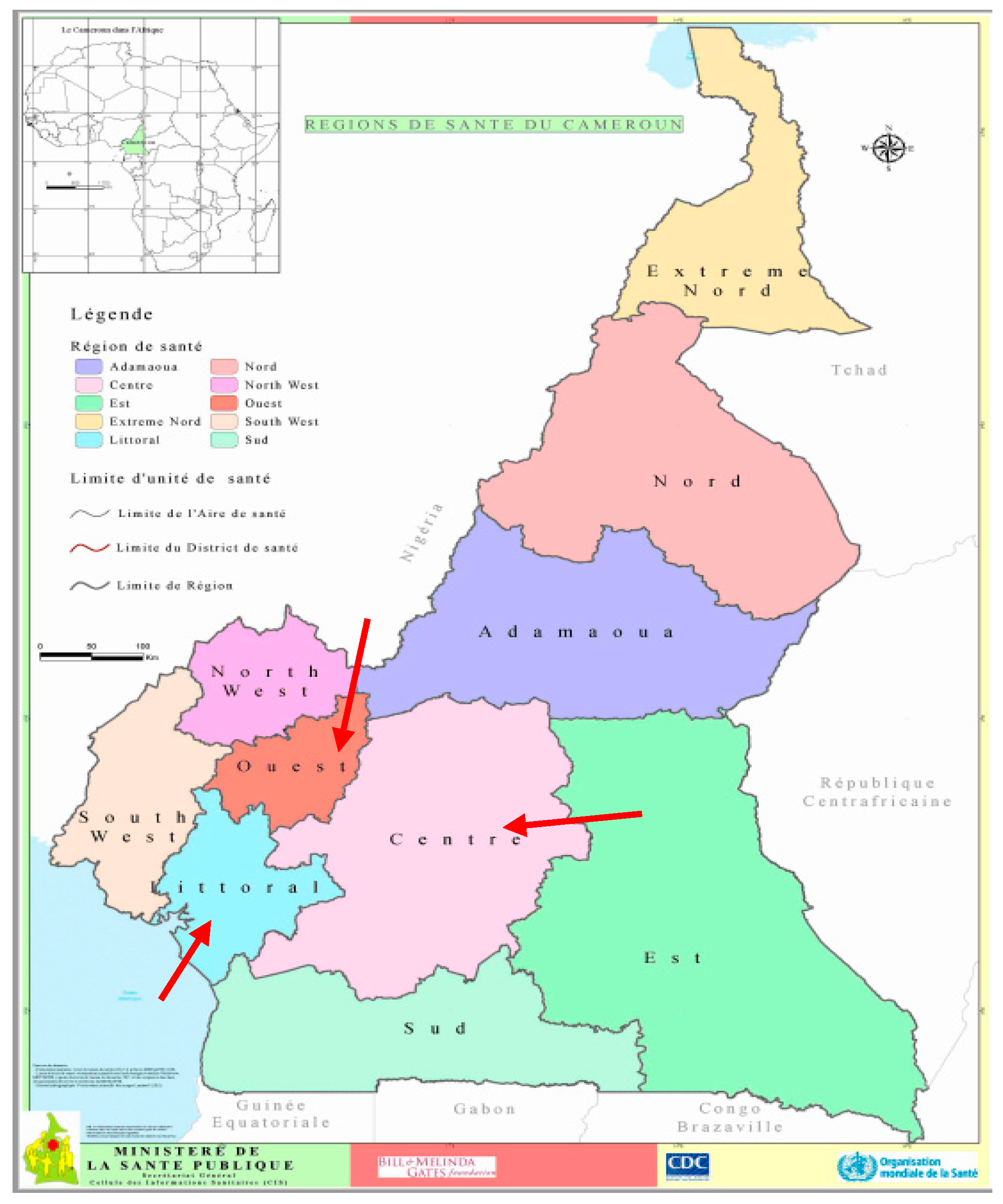

2.1. Settings

2.2. Theoretical Framework of Community Participation in the CDTI/CDI Process

- (1)

- Selection and training of volunteers: During the meeting with the community leader, the health staff explains the concept of CDTI. After that, in general meetings with all the inhabitants, the community: Decides whether or not to adopt the CDTI; decides on the schedule and the process; decides on the selection and remuneration of Community Directed Distributors (CDDs). Following these decisions, the community informs the health worker, who performs the training of the CDDs selected by the community. The first step ends with the census of the community by the CDDs, who then order ivermectin accordingly from the health worker;

- (2)

- Ivermectin collection and distribution: At the date decided by the entire community, the selected and trained CDDs distribute ivermectin. They are also responsible for monitoring eventual side effects. Minor ones are treated by the CDDs and in case of severe side effects they refer to the nearest health facility. At the end of the treatment the CDDs send their reports to the local health staff. They also report to the entire community and the community adjusts its resolutions for the next session. At this stage the role of the local health staff is to monitor the treatment records during visits to communities;

- (3)

- Repeating treatment each year: CDD selection and (re) training is done every year (or every two years).

2.3. Study Design and Participant Selection

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

- -

- Informed consent was verbally obtained;

- -

- Data were safely stored in a computer with password-coded access;

- -

- The names of respondents and of their origins were coded in the final manuscript into “villages”, so we had village 1 through village 6.

3. Results

3.1. CDTI Process and Roles Distribution According to Communities

3.1.1. Selection and Training of Volunteers

“[to be a CDD] … it’s a matter of relationship, meaning that you already have your person who is in front, who is perhaps in the health, who is in a health center where the information about vaccination campaign is released. That person is asked if he knows available people to perform vaccination or to distribute Mectizan; it is now up to him to take his relatives.”(Female participant, FGD Youth, Village 1)

“This is where [the CHA’s name] said: ‘I take you off, I’ll now work with Youth. This is when he recruits the two young girls who presently share Mectizan…”.(Female participant, FGD Youth, Village 3)

3.1.2. Ivermectin Collection and Distribution

3.1.3. Repeating Treatment Each Year

3.2. Perceived Roles of Communities and Their Expectations for CDTI

3.2.1. Passive Role of the Communities in the CDTI

“By the time we had to set a health committee, the chiefs were asked to choose in their villages people of good character. Well, especially since it’s a volunteer job, someone should not go there ask for a salary”(Community Leader, Individual Interview, Village 2)

“We are only like the spectators”.(Female Participant, FGD Youth, Village 1)

3.2.2. Obtaining Communities’ Expectations from CDTI Was Difficult

“For the prevention …, the tragedy here in our village, and we reproach it to the health service, I would even say the departmental health service: we have no campaigns. We do not have prevention campaigns, so I would say in one word that we are not assisted (…), as concerns screenings, as concerns advices, as concerns encouragement.”(Community Leader, Individual Interview, Village 2)

“We will sit on what basis? Yet if we had a health hut in this village here, we would understand that health is important since the nurses are there.”(Male Participant, FGD Elders, Village 3)

3.3. Factors That Can Influence Community Participation

3.3.1. Local Organization of CDTI and Information Sharing

“So, the information was not well relayed, it is also necessary. We must be informed before, so that we can properly prepare and organize ourselves”(Female Participant, FGD Youth, Village 1)

“The chief of the [health] area told my husband that: ‘well, I see what you’re doing on the road there, it’s a waste time, (…) I must take you too, also benefit from this side’”(Female Participant, FGD Elders, Village 5)

3.3.2. Rapidly Growing Economic Background

“You know that Madam, that youth association, what really concerns us is, really living in society, and growing up as well”.(Male Participant, FGD Youth, Village 6)

“[F:] Life in the village is difficult, is difficult! [M:] If you don’t work, you have nothing”(Female [F] and Male [M] Participants, FGD Youth, Village 3)

3.3.3. Community Involvement in Existing Activities: Examples of Sanitation Campaigns and of Security Committees

“Health starts with cleanliness”.(Male Participant, FGD Youth, Village 6)

“Some people say that the difference is that, self-defence is for our own safety, but Mectizan, he sees that he doesn’t gain anything in that.”.(Female Participant, FDG Youth, Village 1)

3.3.4. Importance of Annual Training and Recycling of CDDs

“That system of community agents recycling is good! Because you can’t go tell people that: ‘do this’, when you yourself do not know anything! How can you talk to someone about health while you do not know anything?”(Canton Leader, Individual Interview, Village 1)

4. Discussion

4.1. Community Participation as a Process Instead of An Intervention

4.2. The Challenge of Financial Ownership of Public Health Activities

4.3. Strengthening the Operational Level Health Staff

4.4. Public Policies Reforms

4.5. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIDS | acquired immunodeficiency syndrome |

| APOC | African program for onchocerciasis control |

| CBIT | community based ivermectin treatment |

| CDDs | community directed distributors |

| CDI | community directed interventions |

| CDTI | community directed treatment with ivermectin |

| CHAs | chiefs of health area |

| CP | community participation |

| FGDs | focus group discussions |

| HD | health district |

| HIV | human immunodeficiency virus |

| LMICs | low and middle income countries |

| NGDOs | non-governmental development organizations |

| PHC | primary health care |

| SSH | sectoral strategy for health |

| WHO | world health organization |

References

- International Conference on Primary Health Care. Declaration of Alma-Ata. WHO Chron. 1978, 32, 428–430. [Google Scholar]

- Lawn, E.J.; Rohde, J.; Rifkin, S.; Were, M.; Paul, V.K.; Chopra, M. Alma-Ata 30 years on: Revolutionary, relevant, and time to revitalise. Lancet 2008, 372, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifkin, S.B. Lessons from community participation in health programmes: A review of the post Alma-Ata experience. Int. Health 2009, 1, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walley, J.; Lawn, E.J.; Tinker, A.; De Francisco, A.; Chopra, M.; Rudan, I.; Bhutta, A.Z.; Black, E.R. Primary health care: Making Alma-Ata a reality. Lancet 2008, 372, 1001–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hone, T.; Macinko, J.; Millett, C. Revisiting Alma-Ata: What is the role of primary health care in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals? Lancet 2018, 392, 1461–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PMNCH|Astana Declaration: New Global Commitment to Primary Health Care for All. Available online: http://www.who.int/pmnch/media/news/2018/astana-declaration/en/ (accessed on 16 November 2018).

- George, A.S.; Mehra, V.; Scott, K.; Sriram, V. Community Participation in Health Systems Research: A Systematic Review Assessing the State of Research, the Nature of Interventions Involved and the Features of Engagement with Communities. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Primary Health Care: Now More Than Ever; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Amazigo, U.V.; Obono, M.; Dadzie, K.Y.; Remme, J.; Jiya, J.; Ndyomugyenyi, R.; Roungou, J.B.; Noma, M.; Sékétéli, A. Monitoring community-directed treatment programmes for sustainability: Lessons from the African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control (APOC). Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 2002, 96, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homeida, M.; Braide, E.; Elhassan, E.; Amazigo, U.V.; Liese, B.; Benton, B.; Noma, M.; Etya’Ale, D.; Dadzie, K.Y.; Kale, O.O.; et al. APOC’s strategy of community-directed treatment with ivermectin (CDTI) and its potential for providing additional health services to the poorest populations. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 2002, 96, S93–S104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO|Community-Directed Treatment with Ivermectin (CDTI). Available online: http://www.who.int/apoc/cdti/en/ (accessed on 29 October 2018).

- World Health Organization. Community-Directed Interventions for Major Health Problems in Africa; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Burmeister, H.; Kalambayi, P.K.; Koulischer, G.; Oladepo, O.; Philippon, B.A.; Tarimo, E. African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control (APOC). Report of the External Evaluation; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control. Report of the External Mid-Term Evaluation of the African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control; WHO Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Meredith, S.E.O.; Cross, C.; Amazigo, U.V. Empowering communities in combating river blindness and the role of NGOs: Case studies from Cameroon, Mali, Nigeria, and Uganda. Health Res Policy Syst. 2012, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, C.; Callahan, K.; Katabarwa, M.; Richards, F.; Hopkins, D.; Withers, P.C.; Buyon, L.E.; McFarland, D. The Contributions of Onchocerciasis Control and Elimination Programs toward the Achievement of the Millennium Development Goals. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, 0003703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katabarwa, M.N.; Habomugisha, P.; Richards, F.O.; Hopkins, D. Community-directed interventions strategy enhances efficient and effective integration of health care delivery and development activities in rural disadvantaged communities of Uganda. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2005, 10, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyapong, M.; Gyapong, J.O.; Owusu-Banahene, G. Community-directed treatment: The way forward to eliminating lymphatic filariasis as a public-health problem in Ghana. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 2001, 95, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wamae, N.; Njenga, S.M.; Kisingu, W.M.; Muthigani, P.W.; Kiiru, K. Community-directed treatment of lymphatic filariasis in Kenya and its role in the national programmes for elimination of lymphatic filariasis. Afr. J. Health Sci. 2006, 13, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amazigo, U.V.; Leak, S.G.; Zoure, H.G.; Njepuome, N.; Lusamba-Dikassa, P.-S. Community-driven interventions can revolutionise control of neglected tropical diseases. Trends Parasitol. 2012, 28, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The CDI Study Group. Community-directed interventions for priority health problems in Africa: Results of a multicountry study. Bull. World Health Org. 2010, 88, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministère de la Santé Publique-Cameroun. Stratégie Intégrée de Mise en Oeuvre des Activités sous Directives Communautaires au Cameroun 2016–2017. Unpublished work. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Amazigo, U.; Okeibunor, J.; Matovu, V.; Zouré, H.; Bump, J.; Sékétéli, A. Performance of predictors: Evaluating sustainability in community-directed treatment projects of the African programme for onchocerciasis control. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 64, 2070–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katabarwa, M.; Habomugisha, P.; Eyamba, A.; Agunyo, S.; Mentou, C. Monitoring ivermectin distributors involved in integrated health care services through community-directed interventions—A comparison of Cameroon and Uganda experiences over a period of three years (2004–2006). Trop. Med. Int. Health 2010, 15, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dissak-Delon, F.N.; Kamga, G.-R.; Humblet, P.C.; Robert, A.; Souopgui, J.; Kamgno, J.; Essi, M.J.; Ghogomu, S.M.; Godin, I. Adherence to ivermectin is more associated with perceptions of community directed treatment with ivermectin organization than with onchocerciasis beliefs. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senyonjo, L.; Oye, J.; Bakajika, D.; Biholong, B.; Tekle, A.; Boakye, D.; Schmidt, E.; Elhassan, E. Factors Associated with Ivermectin Non-Compliance and Its Potential Role in Sustaining Onchocerca volvulus Transmission in the West Region of Cameroon. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, 0004905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duamor, C.T.; Datchoua-Poutcheu, F.R.; Ndongmo, W.P.C.; Yoah, A.T.; Njukang, E.; Kah, E.; Maingeh, M.S.; Kengne-Ouaffo, J.A.; Tayong, D.B.; Enyong, P.A.; et al. Programmatic factors associated with the limited impact of Community-Directed Treatment with Ivermectin to control Onchocerciasis in three drainage basins of South West Cameroon. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamga, G.-R.; Dissak-Delon, F.N.; Nana-Djeunga, H.C.; Biholong, B.D.; Ghogomu, S.M.; Souopgui, J.; Kamgno, J.; Robert, A. Audit of the community-directed treatment with ivermectin (CDTI) for onchocerciasis and factors associated with adherence in three regions of Cameroon. Parasites Vectors 2018, 11, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rifkin, S.B.; Muller, F.; Bichmann, W. Primary health care: On measuring participation. Soc. Sci. Med. 1988, 26, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, A.K.; Hewitt, G.; Rifkin, S. Chasing the dragon: Developing indicators for the assessment of community participation in health programmes. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 1102–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippman, S.A.; Neilands, T.B.; Leslie, H.H.; Maman, S.; MacPhail, C.; Twine, R.; Peacock, D.; Kahn, K.; Pettifor, A. Development, Validation, and Performance of a Scale to Measure Community Mobilization. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 157, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO|Setting up Community-Directed Treatment with Ivermectin (CDTI): How It Works and Who Does What. Available online: http://www.who.int/apoc/cdti/howitworks/en/ (accessed on 19 October 2018).

- Thomas, D.R. A General Inductive Approach for Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation Data. Am. J. Eval. 2006, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzinger, J. Qualitative research. Introducing focus groups. BMJ 1995, 311, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, P.; Prime Ministry, Yaoundé, Cameroon. Décret N° 2014/2217/PM du 24 Juillet 2014 Portant Revalorisation du Salaire Minimum Interprofessionnel Garanti (SMIG). Personal communication, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Habomugisha, P.; Agunyo, S.; McKelvey, A.C.; Ogweng, N.; Kwebiiha, S.; Byenume, F.; Male, B.; McFarland, D.; Katabarwa, M.N. Traditional kinship system enhanced classic community-directed treatment with ivermectin (CDTI) for onchocerciasis control in Uganda. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2010, 104, 265–272. [Google Scholar]

- Ramaiah, K.D.; Kumar, K.N.V.; Chandrakala, A.V.; Augustin, D.J.; Appavoo, N.C.; Das, P.K. Effectiveness of community and health services-organized drug delivery strategies for elimination of lymphatic filariasis in rural areas of Tamil Nadu, India. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2001, 6, 1062–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dissak-Delon, F.N.; Kamga, G.-R.; Humblet, P.C.; Robert, A.; Souopgui, J.; Kamgno, J.; Ghogomu, S.M.; Godin, I. Barriers to the National Onchocerciasis Control Program at operational level in Cameroon: A qualitative assessment of stakeholders’ views. Parasit Vectors 2019, 12, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyanda, O.F.; Akinyemi, O.O. Our chairman is very efficient: Community participation in the delivery of primary health care in Ibadan, Southwest Nigeria. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2017, 27, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sombié, I.; Amendah, D.; Soubeiga, K.A. Les perceptions locales de la participation communautaire à la santé au Burkina Faso. Santé Publique 2015, 27, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyaya, O.C.; Rifkin, S.B. Health sector reforms in Kenya: An examination of district level planning. Health Policy 2003, 64, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndjepel, J.; Ngangue, P.; Elanga, E.V.M. Promotion de la santé au Cameroun: État des lieux et perspectives. Santé Publique 2014, S1, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Public Health (MOPH). Health Sector Strategy 2016–2027; MOPH Press: Yaoundé, Cameroon, 2016.

- Lancet, T. Grand convergence: A future sustainable development goal? Lancet 2014, 383, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, A.D.; Yamey, G.; Schäferhoff, M.; Adeyi, O.; Alleyne, G.; Alwan, A.; Berkley, S.; Feachem, R.; Frenk, J.; Ghosh, G.; et al. Alma-Ata at 40 years: Reflections from the Lancet Commission on Investing in Health. Lancet 2018, 392, 1434–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, O.I.; Jegede, A.S.; Falade, O.C.; Sommerfeld, J. Assessing resources for implementing a community directed intervention (CDI) strategy in delivering multiple health interventions in urban poor communities in Southwestern Nigeria: A qualitative study. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2013, 2, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odhiambo, G.O.; Musuva, R.M.; Odiere, M.R.; Mwinzi, P.N. Experiences and perspectives of community health workers from implementing treatment for schistosomiasis using the community directed intervention strategy in an informal settlement in Kisumu City, western Kenya. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Côté, L.; Turgeon, J. Comment lire de façon critique les articles de recherche qualitative en médecine. Pédagogie Médicale 2002, 3, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frambach, J.M.; van der Vleuten, C.P.; Durning, S.J. AM last page. Quality criteria in qualitative and quantitative research. Acad. Med. 2013, 88, 552. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Activities | Actors Responsible of the Activities | Interlocutors/Beneficiaries | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PRE-COMMUNITY PHASE | Advocacy | Partners, NGDOs, National Level Health Planners | National, sub-national and district planners (in health and other partners from public/private sectors) |

| Generate health policies and guidelines for the CDI intervention package | National Level Health Planners | Regional, District and Health area officials | |

| Training of the District and Health Area Staff | National/Regional health staff | District and Health area officials | |

| COMMUNITY PHASE | Introduce to the head of a community | Health Area Official | Community leader |

| Explain the CDTI principles to the community | Health Area Official | Entire community | |

| Decision to adopt the CDTI strategy; Planning of period and modalities of ivermectin distribution (how and where); Election of CDDs and decision of their incentive’s modalities | Entire community | Entire community | |

| Feed Back to the Health Area Officials | Entire community | Health Area Official | |

| Training of CDDs | Health Area Official | Selected CDDs | |

| Census of the community and estimation of ivermectin doses needed | Selected CDDs | Entire community | |

| Collection of ivermectin from the Health Area Officials and distribution to the community | Selected CDDs | Entire community | |

| Monitoring of the community distribution process | Health Area Official | Selected CDDs | |

| Community Auto monitoring of the results of the intervention | Entire community | Entire community | |

| Report of distribution results to the Health System | Entire community | Health Area Official |

| Participants | Role | Gender | Qualification/Profession |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participant 1 | community leader | Male | community leader |

| Participant 2 | community leader | Male | community leader |

| Participant 3 | canton leader | Male | canton leader |

| Participant 4 | community leader | Male | farmer |

| Participant 5 | community leader | Male | farmer |

| Participant 6 | community leader | Male | trader |

| Participant 7 | community leader | Male | self employed |

| Participant 8 | CDTI averse | Male | farmer/trader |

| Participant 9 | CDTI averse | Male | farmer/trader |

| Participant 10 | CDTI averse | Female | trader |

| Participant 11 | CDTI averse | Female | farmer |

| Number of Participants | Gender Distribution | Age Description of the Group | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FGD1 | 7 | 7F | elders (≥35 years) |

| FGD2 | 5 | 2F/3M | youth (16–25 years) |

| FGD3 | 9 | 5F/4M | elders (≥35 years) |

| FGD4 | 8 | 5F/3M | youth (16–25 years) |

| FGD5 | 6 | 2F/4M | youth (16–25 years) |

| FGD6 | 6 | 3F/3M | elders (≥35 years) |

| FGD7 | 8 | 5F/3M | elders (≥35 years) |

| FGD8 | 8 | 2F/6M | youth (16–25 years) |

| FGD9 | 6 | 6M | elders (≥35 years) |

| FGD10 | 14 | 8F/6M | youth (16–25 years) |

| Activities | Actors Responsible of the Activities According to WHO/APOC Theory | Actors Conducting the Activities According to Our Participants’ Views |

|---|---|---|

| Introduce to the head of a community | Health Area Official | Health Area Official |

| Explain the CDTI principles to the community | Health Area Official, during a general assembly | Not Done1 |

| Decision to adopt the CDTI strategy; Planning of period and modalities of ivermectin distribution (how and where); Nomination of CDDs and decision of their incentive’s modalities | Entire community | Health Area Official |

| Feed Back to the Health Area Officials | Entire community | Not Done |

| Training of CDDs | Health Area Official | Health Area Official |

| Census of the community and estimation of ivermectin doses needed | Selected CDDs | Selected CDDs |

| Collection of ivermectin from the Health Area Officials and distribution to the community | Selected CDDs | Selected CDDs |

| Monitoring of the community distribution process | Health Area Official | Not discussed with the participants |

| Community Auto monitoring of the results of the intervention | Entire community | Not Done |

| Report of distribution results to the Health System | Entire community | Selected CDDs |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dissak-Delon, F.N.; Kamga, G.-R.; Humblet, P.C.; Robert, A.; Souopgui, J.; Kamgno, J.; Ghogomu, S.M.; Godin, I. Do Communities Really “Direct” in Community-Directed Interventions? A Qualitative Assessment of Beneficiaries’ Perceptions at 20 Years of Community Directed Treatment with Ivermectin in Cameroon. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2019, 4, 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed4030105

Dissak-Delon FN, Kamga G-R, Humblet PC, Robert A, Souopgui J, Kamgno J, Ghogomu SM, Godin I. Do Communities Really “Direct” in Community-Directed Interventions? A Qualitative Assessment of Beneficiaries’ Perceptions at 20 Years of Community Directed Treatment with Ivermectin in Cameroon. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2019; 4(3):105. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed4030105

Chicago/Turabian StyleDissak-Delon, Fanny Nadia, Guy-Roger Kamga, Perrine Claire Humblet, Annie Robert, Jacob Souopgui, Joseph Kamgno, Stephen Mbigha Ghogomu, and Isabelle Godin. 2019. "Do Communities Really “Direct” in Community-Directed Interventions? A Qualitative Assessment of Beneficiaries’ Perceptions at 20 Years of Community Directed Treatment with Ivermectin in Cameroon" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 4, no. 3: 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed4030105

APA StyleDissak-Delon, F. N., Kamga, G.-R., Humblet, P. C., Robert, A., Souopgui, J., Kamgno, J., Ghogomu, S. M., & Godin, I. (2019). Do Communities Really “Direct” in Community-Directed Interventions? A Qualitative Assessment of Beneficiaries’ Perceptions at 20 Years of Community Directed Treatment with Ivermectin in Cameroon. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 4(3), 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed4030105